Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of

Arctic exploration

Arctic exploration is the physical exploration of the Arctic region of the Earth. It refers to the historical period during which mankind has explored the region north of the Arctic Circle. Historical records suggest that humankind have explored ...

led by

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Sir

John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer and colonial administrator. After serving in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, he led two expeditions into the Northern Canada, Canadia ...

that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, and , and was assigned to traverse the last unnavigated sections of the

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

in the

Canadian Arctic

Northern Canada (), colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada, variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories a ...

and to record magnetic data to help determine whether a better understanding could aid navigation. The expedition met with disaster after both ships and their crews, a total of 129 officers and men, became icebound in

Victoria Strait near

King William Island in what is today the Canadian territory of

Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

. After being icebound for more than a year, ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' were abandoned in April 1848, by which point two dozen men, including Franklin, had died. The survivors, now led by Franklin's second-in-command,

Francis Crozier, and ''Erebus''s captain,

James Fitzjames, set out for the Canadian mainland and disappeared, presumably having perished.

Pressed by Franklin's wife,

Jane, and others, the

Admiralty launched a search for the missing expedition in 1848. In the many subsequent searches in the decades afterwards, several artefacts from the expedition were discovered, including the remains of two men, which were returned to Britain. A series of scientific studies in modern times suggested that the men of the expedition did not all die quickly.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

,

starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

,

lead poisoning

Lead poisoning, also known as plumbism and saturnism, is a type of metal poisoning caused by lead in the body. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, irritability, memory problems, infertility, numbness and paresthesia, t ...

or

zinc deficiency

Zinc deficiency is defined either as insufficient body levels of zinc to meet the needs of the body, or as a zinc blood level below the normal range. However, since a decrease in blood concentration is only detectable after long-term or severe ...

and diseases including

scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

, along with general exposure to a hostile environment while lacking adequate clothing and nutrition, killed everyone on the expedition in the years after it was last sighted by a whaling ship in July 1845. Cut marks on some of the bones recovered during these studies also supported allegations of

cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

reported by Franklin searcher

John Rae in 1854.

Despite the expedition's notorious failure, it did succeed in exploring the vicinity of one of the many Northwest Passages that would eventually be discovered.

Robert McClure led

one of the expeditions that investigated the fate of Franklin's expedition, a voyage which was also beset by great challenges and later controversies. McClure's expedition returned after finding an ice-bound route that connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.

The Northwest Passage was not navigated by boat until 1906, when

Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

traversed the passage on the ''

Gjøa''.

In 2014, a search team led by

Parks Canada

Parks Canada ()Parks Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Parks Canada Agency (). is the agency of the Government of Canada which manages the country's 37 National Parks, three National Marine Co ...

located the wreck of ''Erebus'' in the eastern portion of

Queen Maud Gulf. Two years later, the Arctic Research Foundation found the wreck of ''Terror'' south of King William Island, in the body of water named

Terror Bay.

Research and dive expeditions are an annual occurrence at the wreck sites, now protected as a combined

National Historic Site called the

Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site.

Background

The search by Europeans for a western shortcut by sea from Europe to Asia began with the voyages of Portuguese and Spanish explorers such as

Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( – 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the Cape Agulhas, southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lies ...

,

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama ( , ; – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman who was the Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, first European to reach India by sea.

Da Gama's first voyage (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

and

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

in the 15th century. By the mid-19th century numerous exploratory expeditions had been mounted. These voyages, when successful, added to the sum of European geographic knowledge about the

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

, particularly North America. As that knowledge grew, exploration gradually shifted towards the

Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

.

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century voyagers who made geographic discoveries about North America included

Martin Frobisher,

John Davis,

Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the Northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

and

William Baffin

William Baffin ( – 23 January 1622) was an English navigator, explorer and cartographer. He is best known for his attempt to find the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans, during which Baffin became the first European to disc ...

. In 1670 the incorporation of the

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

(HBC) led to further exploration of the Canadian coastlines, interior and adjacent Arctic seas. In the 18th century explorers of this region included

James Knight,

Christopher Middleton,

Samuel Hearne,

James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

,

Alexander MacKenzie and

George Vancouver

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain George Vancouver (; 22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for leading the Vancouver Expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern West Coast of the Uni ...

. By 1800 their discoveries had conclusively demonstrated that no

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans existed in the temperate latitudes.

In 1804 Sir

John Barrow became Second Secretary of the

Admiralty, a post he held until 1845. Barrow began pushing for the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

to find a Northwest Passage over the top of Canada and to navigate toward the

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

, organising a major series of expeditions. Over those four decades explorers including

John Ross;

David Buchan;

William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Passa ...

;

Frederick William Beechey;

James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer of both the northern and southern polar regions. In the Arctic, he participated in two expeditions led by his uncle, Sir John Ross, John ...

(nephew of John Ross);

George Back

Admiral Sir George Back (6 November 1796 – 23 June 1878) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer of the Canadian Arctic, naturalist and artist. He was born in Stockport.

Career

As a boy, he went to sea as a volunteer in the frigate ...

;

Peter Warren Dease and

Thomas Simpson led productive expeditions to the

Canadian Arctic

Northern Canada (), colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada, variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories a ...

. Among those explorers was

John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer and colonial administrator. After serving in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, he led two expeditions into the Northern Canada, Canadia ...

, who first travelled to the region in 1818 as second-in-command of an expedition towards the North Pole on the ships ''Dorothea'' and ''Trent''. Franklin was subsequently leader of two overland expeditions to and along the Canadian Arctic coast, in 1819–1822 and 1825–1827.

By 1845 the combined discoveries of all these expeditions had reduced the unknown parts of the Canadian Arctic that might contain a Northwest Passage to a quadrilateral area of about . It was in this unexplored area that the next expedition was to sail, heading west through

Lancaster Sound, then west and south – however ice, land and other obstacles might allow – with the goal of finding a Northwest Passage. The distance to be navigated was roughly .

Preparations

Command

In 1845, leading Admiralty figure

Sir John Barrow was 82 years old and nearing the end of his career. He felt that the expeditions were close to finding a Northwest Passage, perhaps through what Barrow believed to be an ice-free

Open Polar Sea around the North Pole. Barrow deliberated over who should command the next expedition. Parry, his first choice, was tired of the Arctic and politely declined. His second choice, James Clark Ross, also declined because he had promised his new wife that he had finished

polar exploration. His third choice,

James Fitzjames, was rejected by the Admiralty for his youth. Barrow also considered Back but thought he was too argumentative.

Francis Crozier, another candidate, declined out of modesty. Reluctantly, Barrow settled on the 59-year-old Franklin.

The expedition was to consist of two ships, and , both of which had been used for

James Clark Ross' expedition to the Antarctic in 1839–1843, during which Crozier had commanded ''Terror''. Franklin was given command of ''Erebus'', with Fitzjames as the vessel's second-in-command; Crozier was appointed his

executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization.

In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer ...

and was again made

commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

of ''Terror''. Franklin received command of the expedition on 7 February 1845, and his official instructions on 5 May 1845.

Ships, provisions and personnel

''Erebus'' (378 tons

bm) and ''Terror'' (331 tons bm) were sturdily built and well equipped, including with several recent inventions.

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

s were fitted, driving a single

screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

in each vessel; these engines were converted former

locomotives

A locomotive is a rail vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. Traditionally, locomotives pulled trains from the front. However, push–pull operation has become common, and in the pursuit for longer and heavier freight train ...

from the

London & Croydon Railway. The ships could make on steam power, or travel under wind power to reach higher speeds and/or save fuel.

Other advanced technology in the ships included reinforced

bows constructed of heavy beams and iron plates, an internal steam heating system for the comfort of the crew in polar conditions, and a system of iron wells that allowed the screw propellers and iron rudders to be withdrawn into the hull to protect them from damage. The ships also carried libraries of more than 1,000 books and three years' supply of food, which included

tinned soup and vegetables,

,

pemmican

Pemmican () (also pemican in older sources) is a mixture of tallow, dried meat, and sometimes dried berries. A calorie-rich food, it can be used as a key component in prepared meals or eaten raw. Historically, it was an important part of indigeno ...

, and several live cattle. The tinned food was supplied from a provisioner, Stephen Goldner, who was awarded the contract on 1 April 1845, a mere seven weeks before Franklin set sail. Goldner worked frantically on the large order of 8,000 tins. The haste required affected

quality control

Quality control (QC) is a process by which entities review the quality of all factors involved in production. ISO 9000 defines quality control as "a part of quality management focused on fulfilling quality requirements".

This approach plac ...

of some of the tins, which were later found to have that was "thick and sloppily done, and dripped like melted candle wax down the inside surface".

Most of the crew were English, many from

Northern England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the Historic counties of England, historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmo ...

, with smaller numbers of Irish,

Welsh and

Scottish members. Two of the sailors were not born in the British Isles: Charles Johnson was from

Halifax,

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

, Canada, and Henry Lloyd was from

Kristiansand

Kristiansand is a city and Municipalities of Norway, municipality in Agder county, Norway. The city is the fifth-largest and the municipality is the sixth-largest in Norway, with a population of around 116,000 as of January 2020, following th ...

, Norway. The only officers with experience of the Arctic were Franklin, Crozier, ''Erebus''

First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

Graham Gore, ''Terror''

assistant surgeon Alexander McDonald, and the two

ice-masters, James Reid (''Erebus'') and Thomas Blanky (''Terror'').

Outward journey and loss

The expedition set sail from

Greenhithe,

Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, on the morning of 19 May 1845, with a crew of 24 officers and 110 men. The ships stopped briefly to take aboard fresh water in

Stromness,

Orkney Islands

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland ...

, in northern Scotland. From there they sailed to

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

with and a transport ship, ''

Barretto Junior''; the passage to Greenland took 30 days.

At the Whalefish Islands in

Disko Bay, on the west coast of Greenland, ten oxen carried on ''Barretto Junior'' were slaughtered for fresh meat which was transferred to ''Erebus'' and ''Terror''. Crew members then wrote their last letters home, which recorded that Franklin had banned swearing and drunkenness. Five men were discharged due to sickness and sent home on ''Rattler'' and ''Barretto Junior'', reducing the final crew to 129 men.

In late July 1845 the

whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

s ''Prince of Wales'' (Captain Dannett) and ''Enterprise'' (Captain Robert Martin) encountered ''Terror'' and ''Erebus'' in

Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; ; ; ), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is sometimes considered a s ...

, where they were waiting for good conditions to cross to

Lancaster Sound. The expedition was never seen again by Europeans.

Only limited information is available for subsequent events, pieced together over the next 150 years by other expeditions, explorers, scientists and interviews with

Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

. The only first-hand information on the expedition's progress is the two-part ''Victory Point Note'' found in the aftermath on King William Island. Franklin's men spent the winter of 1845–46 on

Beechey Island, where three crew members died and were buried. After travelling down Peel Sound through the summer of 1846, ''Terror'' and ''Erebus'' became trapped in ice off

King William Island in September 1846 and are thought never to have sailed again. According to the second part of the Victory Point Note dated 25 April 1848 and signed by Fitzjames and Crozier, the crew had wintered off King William Island in 1846–47 and 1847–48 and Franklin had died on 11 June 1847. The remaining crew had abandoned the ships and planned to walk over the island and across the sea ice towards the

Back River on the Canadian mainland, beginning on 26 April 1848. In addition to Franklin, eight further officers and 15 men had also died by this point. The Victory Point Note is the last known communication of the expedition.

From archaeological finds it is believed that all of the remaining crew died on the subsequent long march

to Back River, most on the island. Thirty or forty men reached the northern coast of the mainland before dying, still hundreds of miles from the nearest outpost of

Western civilisation.

Victory Point note

The Victory Point note was found eleven years later in May 1859 by William Hobson (lieutenant on the

McClintock Arctic expedition)

placed in a cairn on the north-western coast of King William Island. It consists of two parts written on a pre-printed Admiralty form. The first part was written after the first overwintering in 1847 and the second part was added one year later. From the second part it can be inferred that the document was first deposited in a different cairn previously erected by James Clark Ross in 1830 during

John Ross's Second Arctic expedition – at a location Ross named ''Victory Point''.

The first message is written in the body of the form and dates from 28 May 1847.

The second and final part is written largely on the margins of the form owing to a lack of remaining space on the document. It was presumably written on 25 April 1848.

In 1859 Hobson found a second document using the same Admiralty form containing an almost identical duplicate of the first message from 1847 in a cairn a few miles southwest at Gore Point. This document did not contain the second message. From the handwriting it is assumed that all messages were written by Fitzjames. As he did not take part in the landing party that deposited the notes originally in 1847, it is inferred that both documents were originally filled in by Fitzjames on board the ships, with Lieutenant

Graham Gore and Mate

Charles Frederick Des Voeux adding their signatures as members of the landing party. This is further supported by the fact that both documents contain the same factual errors namely the wrong date of the wintering on Beechey Island. In 1848, after the abandonment of the ships and subsequent recovery of the document from the Victory Point cairn, Fitzjames added the second message signed by him and Crozier and deposited the note in the cairn found by Hobson eleven years later.

19th century expeditions

Early searches

After two years had passed with no word from Franklin, public concern grew and

Jane, Lady Franklin, as well as members of Parliament and British newspapers, urged the Admiralty to send a search party. Although the Admiralty said it did not feel any reason to be alarmed, it responded by developing a three-pronged plan which in the spring of 1848 sent an

overland rescue party, led by

John Richardson and

John Rae, down the

Mackenzie River

The Mackenzie River (French: ; Slavey language, Slavey: ' èh tʃʰò literally ''big river''; Inuvialuktun: ' uːkpɑk literally ''great river'') is a river in the Canadian Canadian boreal forest, boreal forest and tundra. It forms, ...

to the Canadian Arctic coast.

Two expeditions by sea were also launched one, led by James Clark Ross, entering the Canadian Arctic archipelago through Lancaster Sound and the other, commanded by Henry Kellett, entering from the Pacific. In addition, the Admiralty offered a reward of £20,000 () "to any Party or Parties, of any country, who shall render assistance to the crews of the Discovery Ships under the command of Sir John Franklin". When the three-pronged effort failed, British national concern and interest in the Arctic increased until "finding Franklin became nothing less than a crusade." Ballads such as "

Lady Franklin's Lament", commemorating Lady Franklin's search for her lost husband, became popular.

Many joined the search. In 1850, eleven British and

two American ships cruised the Canadian Arctic, including the

''Breadalbane'' and her sister ship . Several converged off the east coast of Beechey Island, where the first relics of the expedition were found, including remnants of a winter camp from 1845 to 1846.

Robert Goodsir, surgeon on the brig ''Lady Franklin'', found the graves of

John Torrington,

John Hartnell and

William Braine. No messages from the Franklin expedition were found at this site.

In the spring of 1851, passengers and crew aboard several ships observed a huge iceberg off

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, which bore two vessels, one upright and one on its beam ends. The ships were not examined closely. It was suggested at the time that the ships could have been ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' but it is now known that they were not; it is likely that they were abandoned whaling ships.

In 1852

Edward Belcher was given command of the government Arctic expedition in search of Franklin. It was unsuccessful; Belcher's inability to render himself popular with his subordinates was peculiarly unfortunate on an Arctic voyage and he was not wholly suited to commanding vessels among ice. Four of the five ships (, ''Pioneer'', and ''Intrepid'') were abandoned in

pack ice, for which Belcher was

court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

led but

acquitted

In common law jurisdictions, an acquittal means that the criminal prosecution has failed to prove that the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt of the charge presented. It certifies that the accused is free from the charge of an o ...

.

One of these ships, HMS ''Resolute'', was eventually recovered intact by an American whaler and returned to the United Kingdom. Timbers from the ship were later used to manufacture three desks, one of which, the

''Resolute'' desk, was presented by

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

to

US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed For ...

Rutherford B. Hayes; it has often been chosen by presidents for use in the

Oval Office

The Oval Office is the formal working space of the president of the United States. Part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, it is in the West Wing of the White House, in Washington, D.C.

The oval room has three lar ...

in the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

.

Overland searches

In 1854, Rae, while surveying the

Boothia Peninsula

Boothia Peninsula (; formerly ''Boothia Felix'', Inuktitut ''Kingngailap Nunanga'') is a large peninsula in Nunavut's northern Canadian Arctic, south of Somerset Island. The northern part, Murchison Promontory, is the northernmost point of ...

for the

Hudson Bay Company, discovered further evidence of the expedition's fate. Rae met an

Inuk

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labr ...

near Pelly Bay (now

Kugaaruk, Nunavut) on 21 April 1854, who told him of a party of 35 to 40 white men who had died of

starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

near the mouth of the Back River. Other Inuit confirmed this story, which included reports of

cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

among the dying sailors.

The Inuit showed Rae many objects that were identified as having belonged to members of the Franklin expedition. In particular, Rae bought from the Inuit several silver forks and spoons later identified as belonging to Franklin, Fitzjames,

James Walter Fairholme, and Robert Orme Sargent of the ''Erebus'', and

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier, captain of the ''Terror''. Rae's report was sent to the Admiralty, which in October 1854 urged the HBC to send an expedition down the Back River to search for other signs of Franklin and his men.

Next were Chief Factor James Anderson and HBC employee James Stewart, who travelled north by canoe to the mouth of the Back River. In July 1855, a band of Inuit told them of a group of ''qallunaat'' (

Inuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

for "whites" or "Europeans", perhaps best translated as "foreigners") who had starved to death along the coast. In August, Anderson and Stewart found a piece of wood inscribed with "Erebus" and another that said "Mr. Stanley" (surgeon aboard ''Erebus'') on

Montreal Island

The Island of Montreal (, ) is an island in southwestern Quebec, Canada, which is the site of a number of municipalities, including most of the city of Montreal, and is the most populous island in Canada. It is the main island of the Hochelag ...

in

Chantrey Inlet, where the Back River meets the sea.

Despite the findings of Rae and Anderson, the Admiralty did not plan another search of its own. The Royal Navy officially labelled the crew deceased in service on 31 March 1854. Lady Franklin, failing to convince the government to fund another search, personally commissioned

one more expedition under

Francis Leopold McClintock. The expedition ship, the steam

schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

''

Fox'', bought via public subscription, sailed from

Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

on 2 July 1857.

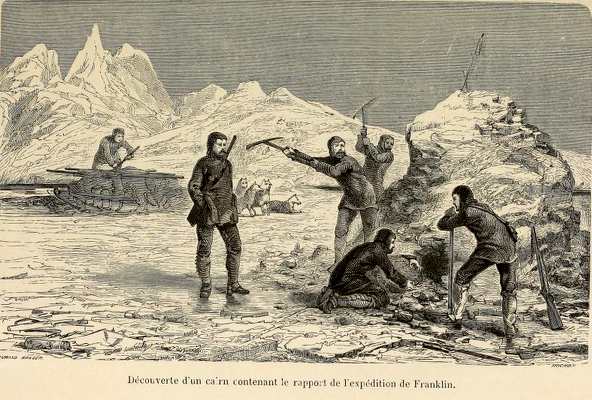

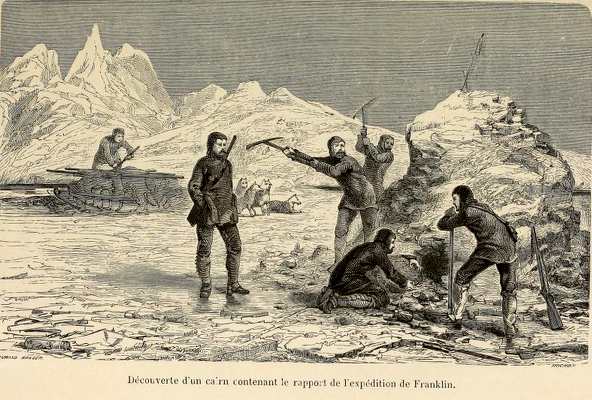

In April 1859,

sled

A sled, skid, sledge, or sleigh is a land vehicle that slides across a surface, usually of ice or snow. It is built with either a smooth underside or a separate body supported by two or more smooth, relatively narrow, longitudinal runners ...

parties set out from ''Fox'' to search on King William Island. On 5 May, the party led by Lieutenant William Hobson discovered the ''Victory Point Note'', which detailed the abandonment of ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'', death of Franklin and other crew members, and the decision by the survivors to march south to the mainland. On the western extreme of King William Island, Hobson also discovered a

lifeboat containing two human skeletons and relics from the Franklin expedition. In the boat was a large amount of abandoned equipment, including boots, silk handkerchiefs, scented soap, sponges, slippers, hair combs and many books, among them a copy of ''

The Vicar of Wakefield'' by

Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith (10 November 1728 – 4 April 1774) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish poet, novelist, playwright, and hack writer. A prolific author of various literature, he is regarded among the most versatile writers of the Georgian e ...

.

Elsewhere, on the island's southern coast, McClintock's searchers found another skeleton. Still clothed, it was searched, and some papers were found, including a seaman's certificate for Chief Petty Officer

Harry Peglar of ''Terror''. Since the uniform was that of a ship's steward, it is more likely that the body was that of Thomas Armitage, gun-room steward on ''Terror'' and a shipmate of Peglar, whose papers he carried. McClintock himself took testimony from the Inuit about the expedition's disastrous end.

Two expeditions between 1860 and 1869 by

Charles Francis Hall, who lived among the Inuit near

Frobisher Bay

Frobisher Bay is an inlet of the Davis Strait in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the southeastern corner of Baffin Island. Its length is about and its width varies from about at its outlet into the Davis Strait ...

on Baffin Island and later at

Repulse Bay

Repulse Bay or Tsin Shui Wan is a bay in the southern part of Hong Kong Island, located in the Southern District, Hong Kong, Southern District, Hong Kong. It is one of the most expensive residential areas in the world.

Geography

Repulse B ...

on the Canadian mainland, found camps, graves and relics on the southern coast of King William Island, but he believed none of the Franklin survivors would be found among the Inuit. In 1869, local Inuit took Hall to a shallow grave on the island containing well-preserved skeletal remains and fragments of clothing. These remains were taken to England and interred beneath the Franklin Memorial at

Greenwich Old Royal Naval College,

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

.

The eminent

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

examined the remains and concluded that they belonged to

Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte, second lieutenant on ''Erebus''. An examination in 2009 suggested that these were actually the remains of

Harry Goodsir, assistant surgeon on ''Erebus''. Although Hall concluded that all of the Franklin crew were dead, he believed that the official expedition records would yet be found under a stone cairn. With the assistance of his guides

Ipirvik and

Taqulittuq, Hall gathered hundreds of pages of Inuit testimony.

Among these materials were accounts of visits to Franklin's ships, and an encounter with a party of white men on the southern coast of King William Island near Washington Bay. In the 1990s, this testimony was extensively researched by

David C. Woodman and was the basis of two books, ''Unravelling the Franklin Mystery'' (1992) and ''Strangers Among Us'' (1995), in which he reconstructs the final months of the expedition. Woodman's narrative challenged existing theories that the survivors all perished over the remainder of 1848 as they marched south from Victory Point, arguing instead that Inuit accounts point strongly to most of the 105 survivors cited by Crozier in his final note actually surviving past 1848, re-manning at least one of the ships and managing to sail it down along the coast of King William Island before it sank, with some crew members surviving as late as 1851.

The hope of finding other additional expedition records led Lieutenant

Frederick Schwatka of the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

to organise an expedition to King William Island between 1878 and 1880. Travelling to

Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

on the schooner ''Eothen'', Schwatka, assembling a team that included Inuit who had assisted Hall, continued north by foot and

dog sled

A dog sled or dog sleigh is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow, a practice known as mushing. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for Sled dog racing, dog sl ...

, interviewing Inuit, visiting known or likely sites of Franklin expedition remains, and wintering on the island. Although Schwatka failed to find the hoped-for papers, in a speech at a dinner given in his honour by the

American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are United States, Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows f ...

in 1880, he said that his expedition had made "the longest sledge journey ever made both in regard to time and distance" of eleven months and four days and , that it was the first Arctic expedition on which the whites relied entirely on the same diet as the Inuit, and that it established the loss of the Franklin records "beyond all reasonable doubt". Schwatka was successful in locating the remains of one of Franklin's men, identified by personal effects as

John Irving

John Winslow Irving (born John Wallace Blunt Jr.; March 2, 1942) is an American and Canadian novelist, short story writer, and screenwriter.

Irving achieved critical and popular acclaim after the international success of his fourth novel '' Th ...

, third lieutenant aboard ''Terror''. Schwatka had Irving's remains returned to Scotland, where they were buried with full honours at

Dean Cemetery

The Dean Cemetery is a historically important Victorian cemetery north of the Dean Village, west of Edinburgh city centre, in Scotland. It lies between Queensferry Road and the Water of Leith, bounded on its east side by Dean Path and o ...

in

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

on 7 January 1881.

The Schwatka expedition found no remnants of the Franklin expedition south of a place now known as Starvation Cove on the

Adelaide Peninsula. This was about north of Crozier's stated goal, the Back River, and several hundred miles away from the nearest Western outpost, on the

Great Slave Lake

Great Slave Lake is the second-largest lake in the Northwest Territories, Canada (after Great Bear Lake), List of lakes by depth, the deepest lake in North America at , and the List of lakes by area, tenth-largest lake in the world by area. It ...

. Woodman wrote of Inuit reports that between 1852 and 1858 Crozier and one other expedition member were seen in the

Baker Lake area, about to the south, where in 1948

Farley Mowat found "a very ancient cairn, not of normal Eskimo construction" inside which were shreds of a hardwood box with

dovetail joint

A dovetail joint or simply dovetail is a joinery technique most commonly used in woodworking joinery (carpentry), including furniture, cabinets, log buildings, and traditional timber framing. Noted for its resistance to being pulled apart, a ...

s.

Modern expeditions

King William Island excavations (1981–1982)

In June 1981,

Owen Beattie, a professor of

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

at the

University of Alberta

The University of Alberta (also known as U of A or UAlberta, ) is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the first premier of Alberta, and Henry Marshall Tory, t ...

, began the 1845–1848 Franklin Expedition Forensic Anthropology Project (FEFAP) when he and his team of researchers and field assistants travelled from

Edmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

to King William Island, traversing the island's western coast as Franklin's men did 132 years before. FEFAP hoped to find artefacts and skeletal remains in order to use modern

forensics

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

to establish identities and causes of death among the lost 129 crewmembers.

Although the trek found archaeological artefacts related to 19th-century Europeans and undisturbed

disarticulated human remains, Beattie was disappointed that more remains were not found. Examining the bones of Franklin crewmen, he noted areas of pitting and scaling often found in cases of

vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits, berries and vegetables. It is also a generic prescription medication and in some countries is sold as a non-prescription di ...

deficiency, the cause of

scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

. After returning to Edmonton, he compared notes from the survey with James Savelle, an Arctic archaeologist, and noticed skeletal patterns suggesting cannibalism. Seeking information about the Franklin crew's health and diet, he sent bone samples to the Alberta Soil and Feed Testing Laboratory for

trace element

__NOTOC__

A trace element is a chemical element of a minute quantity, a trace amount, especially used in referring to a micronutrient, but is also used to refer to minor elements in the composition of a rock, or other chemical substance.

In nutr ...

analysis and assembled another team to visit King William Island. The analysis would find an unexpected level of 226

parts per million

In science and engineering, the parts-per notation is a set of pseudo-units to describe the small values of miscellaneous dimensionless quantity, dimensionless quantities, e.g. mole fraction or mass fraction (chemistry), mass fraction.

Since t ...

(ppm) of lead in the crewman's bones, which was ten times higher than the

control samples, taken from Inuit skeletons from the same geographic area, of 26–36 ppm.

In June 1982, a team made up of Beattie and three students (Walt Kowall, a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Alberta; Arne Carlson, an

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

and

geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

student from

Simon Fraser University

Simon Fraser University (SFU) is a Public university, public research university in British Columbia, Canada. It maintains three campuses in Greater Vancouver, respectively located in Burnaby (main campus), Surrey, British Columbia, Surrey, and ...

in British Columbia; and Arsien Tungilik, an Inuk student and field assistant) was flown to the west coast of King William Island where they retraced some of the steps of McClintock in 1859 and Schwatka in 1878–79. Discoveries during this expedition included the remains of between 6 and 14 men in the vicinity of McClintock's "boat place" and artefacts including a complete boot sole fitted with makeshift cleats for better traction.

Beechey Island excavations and exhumations (1984–1986)

After returning to Edmonton in 1982 and learning of the lead level findings from the 1981 expedition, Beattie struggled to find a cause. Possibilities included the lead solder used to seal the expedition's food tins, other food containers lined with lead foil, food colouring, tobacco products, pewter tableware, and lead-Candle wick, wicked candles. He came to suspect that the problems of lead poisoning compounded by the effects of scurvy could have been lethal for the Franklin crew. Because skeletal lead might reflect lifetime exposure rather than exposure limited to the voyage, Beattie's theory could be tested only by forensic examination of preserved soft tissue as opposed to bone. Beattie decided to examine the graves of the buried crewmen on Beechey Island.

After obtaining legal permission, Beattie's team visited Beechey Island in August 1984 to perform autopsies on the three crewmen buried there. They started with John Torrington, the first crew member to die. After completing Torrington's autopsy and exhuming and briefly examining the body of John Hartnell, the team, pressed for time and threatened by weather, returned to Edmonton with tissue and bone samples. Trace element analysis of Torrington's bones and hair indicated that the crewman "would have suffered severe mental and physical problems caused by lead poisoning". Although the autopsy indicated that pneumonia had been the ultimate cause of the crewman's death, lead poisoning was cited as a contributing factor.

During the expedition, the team visited a place about north of the gravesite to examine fragments of hundreds of food tins discarded by Franklin's men. Beattie noted that the seams were poorly soldered with lead, which had likely come in direct contact with the food.

The release of findings from the 1984 expedition and the photo of Torrington, a 138-year-old corpse well preserved by Arctic permafrost, led to wide media coverage and renewed interest in the Franklin expedition.

Subsequent research has suggested that another potential source for the lead may have been the ships' distilled water systems rather than the tinned food. K. T. H. Farrer argued that "it is impossible to see how one could ingest from the canned food the amount of lead, 3.3 mg per day over eight months, required to raise the PbB to the level 80 μg/dL at which symptoms of lead poisoning begin to appear in adults and the suggestion that bone lead in adults could be 'swamped' by lead ingested from food over a period of a few months, or even three years, seems scarcely tenable." In addition, tinned food was in widespread use within the Royal Navy at that time and its use did not lead to any significant increase in lead poisoning elsewhere.

Uniquely for this expedition, the ships were fitted with converted railway locomotive engines for auxiliary propulsion which required an estimated one tonne of fresh water per hour when steaming. It is highly probable that it was for this reason that the ships were fitted with a unique desalination system which, given the materials in use at the time, would have produced large quantities of water with a very high lead content. William Battersby has argued that this is a much more likely source for the high levels of lead observed in the remains of expedition members than the tinned food.

A further survey of the graves was undertaken in 1986. A camera crew filmed the procedure, shown in a 1988 episode of the American programme ''Nova (American TV series), Nova''. Under difficult field conditions, Derek Notman, a radiologist and medical doctor from the University of Minnesota, and radiology technician Larry Anderson took many X-rays of the crewmen prior to autopsy. Barbara Schweger, an Arctic clothing specialist, and Roger Amy, a pathologist, assisted in the investigation.

Beattie and his team had noticed that someone else had attempted to exhume Hartnell. In the effort, a pickaxe had damaged the wooden lid of his coffin, and the coffin plaque was missing. Research in Edmonton later showed that Sir Edward Belcher, commander of one of the Franklin rescue expeditions, had ordered the exhumation of Hartnell in October 1852, but was thwarted by the permafrost. One month later, Edward A. Inglefield, commander of another rescue expedition, succeeded with the exhumation and removed the coffin's plaque.

Unlike Hartnell's grave, the grave of Private William Braine was largely intact. When he was exhumed, the survey team saw signs that his burial had been hasty. His arms, body and head had not been positioned carefully in the coffin, and one of his undershirts had been put on backwards. The coffin seemed too small for him; its lid had pressed down on his nose. A large copper plaque with his name and other personal data punched into it adorned his coffin lid.

File: 2018-09-30 01 Franklin Camp grave images, Nunavut Canada 2015-09-11.jpg, The four graves at Franklin Camp near the harbour on Beechey Island, Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

, Canada.

File:2018-09-30 02 Franklin Camp grave images, Nunavut Canada 2015-09-11.jpg, (L–R) Three grave stones commemorate John Torrington, William Braine and John Hartnell of the Franklin Expedition. A fourth headstone marks the grave of a sailor named Thomas Morgan who came later in a Franklin search expedition and died at the camp.

NgLj-2 excavations (1992)

In 1992, Franklin scholar Barry Ranford and his colleague, Mike Yarascavitch, discovered human skeletal remains and artefacts of what they suspected to be some of the lost crewmen of the expedition. The site matches the physical description of McClintock's "boat place". In 1993, a team of archaeologists and forensic anthropologists returned to the site, which they referenced as "NgLj-2", on the western shores of King William Island, to excavate these remains. These excavations uncovered nearly 400 bones and bone fragments, and physical artefacts ranging from pieces of clay pipes to buttons and brass fittings. Examination of these bones by Anne Keenleyside, the expedition's forensic scientist, showed elevated levels of lead and many cut-marks "consistent with de-fleshing". On the basis of this expedition, it has become generally accepted that at least some of Franklin's men resorted to cannibalism in their final distress.

A study published in the ''International Journal of Osteoarchaeology'' in 2015 concluded that in addition to the de-fleshing of bones, thirty-five "bones had signs of breakage and 'pot polishing', which occurs when the ends of bones heated in boiling water rub against the cooking pot they are placed in", which "typically occurs in the end stage of cannibalism, when starving people extract the bone marrow, marrow to eke out the last bit of calories and nutrition they can."

King William Island (1994–1995)

In 1994, Woodman organised and led a land search of the area from Collinson Inlet to (modern) Victory Point in search of the buried "vaults" spoken of in the testimony of the contemporary Inuk hunter Supunger. A ten-person team spent ten days in the search, sponsored by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society and filmed by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). No trace of the vaults was found.

In 1995, an expedition was jointly organised by Woodman, George Hobson and American adventurer Steven Trafton with each party planning a separate search. Trafton's group travelled to the Clarence Islands to investigate Inuit stories of a "white man's cairn" there but found nothing. Hobson's party, accompanied by archaeologist Margaret Bertulli, investigated the "summer camp" found a few miles to the south of Cape Felix, where some minor Franklin relics were found. Woodman, with two companions, travelled south from Wall Bay to Victory Point and investigated all likely campsites along this coast, finding only some rusted cans at a previously unknown campsite near Cape Maria Louisa.

Wreck searches (1997–2013)

In 1997, a "Franklin 150" expedition was mounted by the Canadian film company Eco-Nova to use sonar to investigate more of the priority magnetic targets found in 1992. The senior archaeologist was Robert Grenier, assisted by Margaret Bertulli, and Woodman again acted as expedition historian and search coordinator. Operations were conducted from the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker ''Laurier''. Approximately were surveyed, without result, near Kirkwall Island. When detached parties found Franklin relics – primarily copper sheeting and small items – on the beaches of islets to the north of O'Reilly Island the search was diverted to that area, but poor weather prevented significant survey work before the expedition ended. A documentary, ''Oceans of Mystery: Search for the Lost Fleet'', was produced by Eco-Nova about this expedition.

Three expeditions were mounted by Woodman to continue the magnetometer mapping of the proposed wreck sites: a privately sponsored expedition in 2001, and the Irish-Canadian Franklin Search Expeditions of 2002 and 2004. These made use of sled-drawn magnetometers working on the sea ice and completed the unfinished survey of the northern (Kirkwall Island) search area in 2001, and the entire southern O'Reilly Island area in 2002 and 2004. All of the high-priority magnetic targets were identified by sonar through the ice as geological in origin. In 2002 and 2004, small Franklin artefacts and characteristic explorer tent sites were found on a small islet northeast of O'Reilly Island during shore searches.

In August 2008 a new search by

Parks Canada

Parks Canada ()Parks Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Parks Canada Agency (). is the agency of the Government of Canada which manages the country's 37 National Parks, three National Marine Co ...

was announced, to be led by Grenier. This search hoped to take advantage of the improved ice conditions, using side-scan sonar from a boat in open water. Grenier also hoped to draw from newly published Inuit testimony collected by oral historian Dorothy Harley Eber. Some of Eber's informants placed the location of one of Franklin's ships in the vicinity of the Royal Geographical Society Island, an area not searched by previous expeditions. The search was to also include local Inuk historian Louie Kamookak, who had found other significant remains of the expedition and would represent the indigenous culture.

HMS ''Investigator'' became icebound in 1853 while searching for Franklin's expedition and was subsequently abandoned. It was found in shallow water in Mercy Bay on 25 July 2010, along the northern coast of Banks Island in Canada's western Arctic. The Parks Canada team reported that it was in good shape, upright in about of water.

A new search was announced by Parks Canada in August 2013.

Victoria Strait Expedition: wreck of ''Erebus'' (2014)

On 1 September 2014, a larger search by a Canadian team under the banner of the "Victoria Strait Expedition" found two items on Hat Island (Victoria Strait), Hat Island in the Queen Maud Gulf near King William Island: a wooden object, possibly a plug for a deck Hawsehole, hawse, the iron pipe through which the ship's chain cable would descend into the chain locker below; and part of a boat-launching davit bearing the stamps of two Royal Navy broad arrows.

On 9 September 2014, the expedition announced that on 7 September it had located one of Franklin's two ships.

The ship is preserved in good condition, with side-scan sonar picking up even the deck planking. The wreck lies in about of water at the bottom of Wilmot and Crampton Bay in the eastern part of Queen Maud Gulf, west of O'Reilly Island. On 1 October at the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper confirmed the wreck was that of HMS ''Erebus''.

A documentary, ''Hunt for the Arctic Ghost Ship'', was produced by Lion Television for Channel 4's ''Secret History (TV series), Secret History'' series in 2015.

In September 2018, Parks Canada announced that ''Erebus'' had deteriorated significantly. "An upwards buoyant force acting on the decking combined with storm swell in relatively shallow water caused the displacement", according to a spokesperson. The underwater exploration in 2018 totalled only a day and a half due to weather and ice conditions and was to continue in 2019. Also in September 2018, a report provided specifics as to ownership of the ships and contents: the United Kingdom will own the first 65 artefacts brought up from ''Erebus'', while the wreck of both ships and other artefacts will be jointly owned by Canada and the Inuit.

Arctic Research Foundation Expedition: wreck of ''Terror'' (2016)

On 12 September 2016, it was announced that the Arctic Research Foundation expedition had found the wreck of HMS ''Terror'' to the south of King William Island in Terror Bay, at at a depth of , and in "pristine" condition.

In 2018, a team examined the wreck of ''Terror'' using a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) that collected photos and video clips of the ship and a number of artefacts. The group concluded that ''Terror'' had not been left at anchor, since anchor cables were seen to be secured along the bulwarks.

Scientific conclusions

Reasons for failure

The FEFAP field surveys, excavations and exhumations spanned more than ten years. The results of this study showed that the Beechey Island crew had most probably died of pneumonia and perhaps tuberculosis, which was suggested by the evidence of Pott disease discovered in Braine. Toxicological reports pointed to lead poisoning as a likely contributing factor. Blade cut marks found on bones from some of the crew were seen as signs of cannibalism.

Evidence suggested that a combination of cold, starvation and disease including scurvy, pneumonia and tuberculosis, all made worse by lead poisoning, killed everyone in the Franklin expedition. It was also discovered that the cans of provisions mainly eaten by officers were soldered poorly, causing food to rot. This weakening of their immune systems was compounded by the fact that animals caught and eaten by the crew of the expedition contained botulism Type-C.

More recent chemical re-examination of bone and nail samples taken from Hartnell and other crew members has cast doubt on the role of lead poisoning.

A 2013 study determined that the levels of lead present in the crew members' bones had been consistent during their lives, and that there was no Isotopes of lead, isotopic difference between lead concentrated within older and younger bone materials.

Had the crew been poisoned by lead from the solder used to seal the canned food or from the ships' water supplies, both the concentration of lead and its isotopic composition would have been expected to have "spiked" during their last few months.

This interpretation was supported by a 2016 study that suggested the crew's ill health may in fact have been due to malnutrition, and specifically

zinc deficiency

Zinc deficiency is defined either as insufficient body levels of zinc to meet the needs of the body, or as a zinc blood level below the normal range. However, since a decrease in blood concentration is only detectable after long-term or severe ...

, probably due to a lack of meat in their diet.

This study used micro-X-ray fluorescence to map the levels of lead, copper and zinc in Hartnell's thumbnail over the final months of his life, and found that apart from during his last few weeks lead concentrations within Hartnell's body were within healthy limits.

In contrast, levels of zinc were far lower than normal and indicated that Hartnell would have been suffering from chronic zinc deficiency, sufficient to have severely suppressed his immune system and left him highly vulnerable to a worsening of the tuberculosis with which he was already infected.

In the last few weeks of his life, his illness would have caused his body to start breaking down bone, fat and muscle tissues, releasing lead previously stored there into his bloodstream and giving rise to the high lead levels noted in previous analysis of soft tissues and hair.

Franklin's chosen passage down the west side of King William Island took ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' into "a ploughing train of ice ... [that] does not always clear during the short summers", whereas the route along the island's east coast regularly clears in summer and was later used by Roald Amundsen in his successful navigation of the Northwest Passage. The Franklin expedition, locked in ice for two winters in Victoria Strait, was naval in nature and therefore not well-equipped or trained for land travel. Some of the crewmembers heading south from ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' hauled in many items not needed for Arctic survival. McClintock noted a large quantity of heavy goods in the lifeboat at the "boat place" and thought them "a mere accumulation of dead weight, of little use, and very likely to break down the strength of the sledge-crews". The winter of 1846–1847 was unusually harsh for its time, meaning the ship was completely stuck in ice for two successive winters.

Other findings

In 2017, Douglas Stenton, an adjunct professor of anthropology at the University of Waterloo and former director of Nunavut's Department of Heritage and Culture, suggested that four sets of human remains found on King William Island could possibly be women. He initially suspected that DNA testing would not offer up anything more, but to his surprise they registered that there was no Y chromosome, 'Y' chromosomal element to the DNA. Stenton acknowledged that women were known to have served in the Royal Navy in the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries, but he also pointed out that it could be that the DNA had simply degraded as further tests proved ambiguous and he concluded the initial findings were "almost certainly incorrect".

In 1993, three bodies were found at site NgLj-3 near Erebus Bay. The remains had originally been found by McClintock's expedition in 1859, and were rediscovered and buried by Schwatka two decades later. In 2013, a team led by Stenton had the remains exhumed for DNA testing and forensic facial reconstruction. The team's report, published in ''Polar Journal'' in 2015, indicated that the reconstructions of the two intact skulls from the remains resembled Lieutenant Gore and Ice-Master Reid of the ''Erebus''; science later determined the remains could not have belonged to Gore, as the Victory Point note stated that Gore had died before the abandonment of the ships in April 1848.

In May 2021, one of the bodies was positively identified as that of Warrant Officer John Gregory (engineer), John Gregory, an engineer aboard ''Erebus''. A genealogy team tracked down Gregory's great-great-great-grandson, Jonathan Gregory, residing in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, and confirmed the familial match through DNA testing.

In September 2024, researchers Douglas Stenton, Stephen Fratpietro, and Robert W. Park, from the University of Waterloo and Lakehead University, announced that they had positively identified a skeletal mandible as belonging to Captain

James Fitzjames through DNA testing. An unbroken Y-chromosome DNA match was made from a living descendant of Fitzjames's great-grandfather James Gambier; the DNA donor, Nigel Gambier, is second cousin five times removed to Fitzjames. By doing genealogical research, historian Fabiënne Tetteroo determined that Nigel Gambier was an eligible match for Fitzjames. Tetteroo contacted Nigel Gambier and he agreed to provide the DNA sample that conclusively identified Fitzjames. Fitzjames' mandible shows signs of cut marks consistent with cannibalism.

Timeline

Legacy

Historical

The most meaningful outcome of the Franklin expedition was the mapping of several thousand miles of hitherto unsurveyed coastline by expeditions searching for Franklin's lost ships and crew. As Richard Cyriax noted, "the loss of the expedition probably added much more [geographical] knowledge than its successful return would have done". At the same time, it largely quelled the Admiralty's appetite for Arctic exploration. There was a gap of many years before the British Arctic Expedition, Nares expedition and Sir George Nares' declaration there was "no thoroughfare" to the North Pole; his words marked the end of the Royal Navy's historical involvement in Arctic exploration, the end of an era in which such exploits were widely seen by the British public as worthy expenditures of human effort and monetary resources. Given how difficult and risky it was for professional explorers to cross the Northwest Passage, it would be impossible for the average merchant ships of the day to use this route for trade.

An unnamed commentator in ''The Critic (Victorian-era magazine), The Critic'' wrote in 1859, "We think that we can fairly make out the account between the cost and results of these Arctic Expeditions, and ask whether it is worth while to risk so much for that which is so difficult of attainment, and when attained, is so worthless." The navigation of the Northwest Passage in 1903–05 by Roald Amundsen with the ''Gjøa'' expedition ended the centuries-long quest for the route.

[

]

Northwest Passage discovered

Franklin's expedition explored the vicinity of what was ultimately one of many Northwest Passages to be discovered. While the more famous search expeditions were underway in 1850, Robert McClure set out on the little-known McClure Arctic expedition on HMS ''Investigator'' to also investigate the fate of Franklin's voyage. While he did not find much evidence of Franklin's fate, he did finally ascertain an ice-bound route that connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. This was the Prince of Wales Strait, which was far to the north of Franklin's ships.[

On 21 October 1850, the following entry was recorded in 's log:

McClure was knighted for his discovery. While the McClure expedition obviously fared much better than Franklin's voyage, it was similarly beset by immense challenges (including the loss of ''Investigator'' and four winters on the ice) and a number of controversies, including allegations of selfishness and poor planning on McClure's part. His decision to place numerous message cairns along his route ultimately saved his expedition, who were ultimately found and rescued by the crew of .][

In 1855, a British parliamentary committee concluded that McClure "deserved to be rewarded as the discoverer of a Northwest Passage". Today, the question of who actually discovered the Northwest Passage is a subject of controversy, as all the different Passages have varying degrees of navigability. Although he did confirm the first geographical Northwest Passage that is navigable by ship under ideal conditions, McClure is rarely credited in modern times due to his troubled expedition, his poor personal reputation, the fact that his expedition was after Franklin's (who has a claim to be the first discoverer) and the fact that he never traversed the strait that he found, instead choosing to portage over Banks Island.]

Simpson Strait

Members of the Franklin expedition crossed the southern shore of King William Island and made it onto the Canadian mainland; this is evident by the fact that human remains from the expedition have been found inland on the Adelaide Peninsula.

Cultural depictions

Commemoration

For years after the loss of the Franklin expedition, the Victorian media portrayed Franklin as a hero who led his men in the quest for the Northwest Passage. A statue of Franklin in his hometown bears the inscription "Sir John Franklin – Discoverer of the North West Passage", and statues of Franklin outside the Athenaeum Club, London, Athenaeum in London and in Tasmania bear similar inscriptions. Although the expedition's fate, including the possibility of cannibalism, was widely reported and debated, Franklin's standing with the Victorian public was undiminished. This was due in large part to efforts by Lady Franklin to protect her husband's reputation and dispel suggestions of cannibalism – with assistance from prominent figures like Charles Dickens, who asserted that "there is no reason whatever to believe, that any of its members prolonged their existence by the dreadful expedient of eating the bodies of their dead companions". The expedition has been the subject of numerous works of non-fiction.

The mystery surrounding the expedition was the subject of three episodes of the PBS programme ''Nova'', broadcast in 1988, 2006 and 2015; a 2007 television documentary, "Franklin's Lost Expedition", on ''Discovery HD Theatre''; as well as a 2008 Canadian documentary, ''Passage (2008 film), Passage''. In a 2009 episode of the ITV (TV network), ITV travel documentary series ''Billy Connolly: Journey to the Edge of the World'', presenter Billy Connolly and his crew visited Beechey Island, filmed the grave site and gave details of the expedition.

In memory of the lost expedition, one of Canada's Northwest Territories subdivisions was known as the District of Franklin. Including the high Arctic islands, this jurisdiction was abolished when the area was set off into the newly created Nunavut Territory on 1 April 1999.

On 29 October 2009, a special service of thanksgiving was held in the chapel at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, to accompany the rededication of the national monument to Franklin there. The service also included the solemn re-interment of the only remains from ''Erebus'' to be repatriated to England, entombed within the monument in 1873 (previously thought to be Le Vesconte, but may actually have been Goodsir).

For years after the loss of the Franklin expedition, the Victorian media portrayed Franklin as a hero who led his men in the quest for the Northwest Passage. A statue of Franklin in his hometown bears the inscription "Sir John Franklin – Discoverer of the North West Passage", and statues of Franklin outside the Athenaeum Club, London, Athenaeum in London and in Tasmania bear similar inscriptions. Although the expedition's fate, including the possibility of cannibalism, was widely reported and debated, Franklin's standing with the Victorian public was undiminished. This was due in large part to efforts by Lady Franklin to protect her husband's reputation and dispel suggestions of cannibalism – with assistance from prominent figures like Charles Dickens, who asserted that "there is no reason whatever to believe, that any of its members prolonged their existence by the dreadful expedient of eating the bodies of their dead companions". The expedition has been the subject of numerous works of non-fiction.

The mystery surrounding the expedition was the subject of three episodes of the PBS programme ''Nova'', broadcast in 1988, 2006 and 2015; a 2007 television documentary, "Franklin's Lost Expedition", on ''Discovery HD Theatre''; as well as a 2008 Canadian documentary, ''Passage (2008 film), Passage''. In a 2009 episode of the ITV (TV network), ITV travel documentary series ''Billy Connolly: Journey to the Edge of the World'', presenter Billy Connolly and his crew visited Beechey Island, filmed the grave site and gave details of the expedition.

In memory of the lost expedition, one of Canada's Northwest Territories subdivisions was known as the District of Franklin. Including the high Arctic islands, this jurisdiction was abolished when the area was set off into the newly created Nunavut Territory on 1 April 1999.

On 29 October 2009, a special service of thanksgiving was held in the chapel at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, to accompany the rededication of the national monument to Franklin there. The service also included the solemn re-interment of the only remains from ''Erebus'' to be repatriated to England, entombed within the monument in 1873 (previously thought to be Le Vesconte, but may actually have been Goodsir).[Mays, S., et al., New light on the personal identification of a skeleton of a member of Sir John Franklin's last

expedition to the Arctic, 1845, Journal of Archaeological Science (2011), ] The following day, a group of polar authors went to London's Kensal Green Cemetery to pay their respects to the Arctic explorers buried there.

Many other veterans of the searches for Franklin are buried there too, including Admiral Sir Horatio Thomas Austin, Admiral Sir George Back, Admiral Sir Edward Augustus Inglefield, Admiral Bedford Pim, and Admiral Sir John Ross. Franklin's wife, Lady Franklin, is also interred at Kensal Green in the vault and commemorated on a marble cross dedicated to her niece, Sophia Cracroft.

Literary works