Franciscan order on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, merged =

, formation =

, founder =

''Peace and llgood'' , leader_title2 = Minister General , leader_name2 = Fr. Massimo Fusarelli, , leader_title3 = , leader_name3 = , leader_title4 = , leader_name4 = , key_people = , main_organ = , parent_organization =

Third Order of Saint Francis (1447) , secessions = OFM (1897)

OFM Conventual (1517)

OFM Capuchin (1520) , affiliations = , mission = , website = , remarks = , formerly = Order of Observant Friars Minor , footnotes = The Franciscans are a group of related

The Franciscans are a group of related

The name of the original order, (Friars Minor, literally 'Order of Lesser Brothers') stems from Francis of Assisi's rejection of extravagance. Francis was the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, but gave up his wealth to pursue his faith more fully. He had cut all ties that remained with his family, and pursued a life living in solidarity with his fellow brothers in Christ. Francis adopted the simple tunic worn by peasants as the

The name of the original order, (Friars Minor, literally 'Order of Lesser Brothers') stems from Francis of Assisi's rejection of extravagance. Francis was the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, but gave up his wealth to pursue his faith more fully. He had cut all ties that remained with his family, and pursued a life living in solidarity with his fellow brothers in Christ. Francis adopted the simple tunic worn by peasants as the

Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 28 December 2019 He planned and built the In the external successes of the brothers, as they were reported at the yearly general chapters, there was much to encourage Francis. , the first German provincial, a zealous advocate of the founder's strict principle of poverty, began in 1221 from

In the external successes of the brothers, as they were reported at the yearly general chapters, there was much to encourage Francis. , the first German provincial, a zealous advocate of the founder's strict principle of poverty, began in 1221 from

Elias was a lay friar, and encouraged other laymen to enter the order. This brought opposition from many ordained friars and ministers provincial, who also opposed increased centralization of the Order. Gregory IX declared his intention to build a splendid church to house the body of Francis and the task fell to Elias, who at once began to lay plans for the erection of a great basilica at Assisi, to enshrine the remains of the ''Poverello''. In order to build the basilica, Elias proceeded to collect money in various ways to meet the expenses of the building. Elias thus also alienated the zealots in the order, who felt this was not in keeping with the founder's views upon the question of poverty.

The earliest leader of the strict party was

Elias was a lay friar, and encouraged other laymen to enter the order. This brought opposition from many ordained friars and ministers provincial, who also opposed increased centralization of the Order. Gregory IX declared his intention to build a splendid church to house the body of Francis and the task fell to Elias, who at once began to lay plans for the erection of a great basilica at Assisi, to enshrine the remains of the ''Poverello''. In order to build the basilica, Elias proceeded to collect money in various ways to meet the expenses of the building. Elias thus also alienated the zealots in the order, who felt this was not in keeping with the founder's views upon the question of poverty.

The earliest leader of the strict party was

Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 28 December 2019 At the chapter held in May 1227, Elias was rejected in spite of his prominence, and Giovanni Parenti, Minister Provincial of Spain, was elected Minister General of the order. In 1232 Elias succeeded him, and under him the Order significantly developed its ministries and presence in the towns. Many new houses were founded, especially in Italy, and in many of them special attention was paid to education. The somewhat earlier settlements of Franciscan teachers at the universities (in

Elias governed the Order from the center, imposing his authority on the provinces (as had Francis). A reaction to this centralized government was led from the provinces of England and Germany. At the general chapter of 1239, held in Rome under the personal presidency of Gregory IX, Elias was deposed in favor of Albert of Pisa, the former provincial of England, a moderate Observantist. This chapter introduced General Statutes to govern the Order and devolved power from the

Elias governed the Order from the center, imposing his authority on the provinces (as had Francis). A reaction to this centralized government was led from the provinces of England and Germany. At the general chapter of 1239, held in Rome under the personal presidency of Gregory IX, Elias was deposed in favor of Albert of Pisa, the former provincial of England, a moderate Observantist. This chapter introduced General Statutes to govern the Order and devolved power from the  Elias, who had been excommunicated and taken under the protection of Frederick II, was now forced to give up all hope of recovering his power in the Order. He died in 1253, after succeeding by recantation in obtaining the removal of his censures. Under John of Parma, who enjoyed the favor of Innocent IV and

Elias, who had been excommunicated and taken under the protection of Frederick II, was now forced to give up all hope of recovering his power in the Order. He died in 1253, after succeeding by recantation in obtaining the removal of his censures. Under John of Parma, who enjoyed the favor of Innocent IV and

A few years later a new controversy, this time theoretical, broke out on the question of

A few years later a new controversy, this time theoretical, broke out on the question of

This was founded in the hermitage of St. Bartholomew at Brugliano near

This was founded in the hermitage of St. Bartholomew at Brugliano near

Projects for a union between the two main branches of the Order were put forth not only by the Council of Constance but by several popes, without any positive result. By direction of

Projects for a union between the two main branches of the Order were put forth not only by the Council of Constance but by several popes, without any positive result. By direction of

.

The work of the Franciscans in New Spain began in 1523, when three Flemish friars—Juan de Ayora, Pedro de Tecto, and Pedro de Gante—reached the central highlands. Their impact as missionaries was limited at first, since two of them died on Cortés's expedition to Central American in 1524, but Fray Pedro de Gante initiated the evangelization process and studied the

.

The work of the Franciscans in New Spain began in 1523, when three Flemish friars—Juan de Ayora, Pedro de Tecto, and Pedro de Gante—reached the central highlands. Their impact as missionaries was limited at first, since two of them died on Cortés's expedition to Central American in 1524, but Fray Pedro de Gante initiated the evangelization process and studied the

The

The

The

The

The Poor Clares, officially the Order of Saint Clare, are members of a contemplative order of nuns in the

The Poor Clares, officially the Order of Saint Clare, are members of a contemplative order of nuns in the

The Third Order of Saint Francis comprises people who desired to grow in holiness in their daily lives without entering

The Third Order of Saint Francis comprises people who desired to grow in holiness in their daily lives without entering

Within a century of the death of Francis, members of the Third Order began to live in common, in an attempt to follow a more

Within a century of the death of Francis, members of the Third Order began to live in common, in an attempt to follow a more

Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

, founding_location =

, extinction =

, merger =

, type = Mendicant Order of Pontifical Right for men

, status =

, purpose =

, headquarters = Via S. Maria Mediatrice 25, 00165 Rome, Italy

, location =

, coords =

, region =

, services =

, membership = 12,476 members (8,512 priests) as of 2020

, language =

, sec_gen =

, leader_title = Motto

, leader_name = ''Pax et bonum'' ''Peace and llgood'' , leader_title2 = Minister General , leader_name2 = Fr. Massimo Fusarelli, , leader_title3 = , leader_name3 = , leader_title4 = , leader_name4 = , key_people = , main_organ = , parent_organization =

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, subsidiaries = Secular Franciscan Order (1221)Third Order of Saint Francis (1447) , secessions = OFM (1897)

OFM Conventual (1517)

OFM Capuchin (1520) , affiliations = , mission = , website = , remarks = , formerly = Order of Observant Friars Minor , footnotes =

The Franciscans are a group of related

The Franciscans are a group of related mendicant

A mendicant (from la, mendicans, "begging") is one who practices mendicancy, relying chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. In principle, mendicant religious orders own little property, either individually or collectively, and in many inst ...

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

religious orders

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious pract ...

within the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

, these orders include three independent orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor

The Order of Friars Minor (also called the Franciscans, the Franciscan Order, or the Seraphic Order; postnominal abbreviation OFM) is a mendicant Catholic religious order, founded in 1209 by Francis of Assisi. The order adheres to the teachi ...

being the largest contemporary male order), orders for women religious such as the Order of Saint Clare, and the Third Order of Saint Francis open to male and female members. They adhere to the teachings and spiritual disciplines of the founder and of his main associates and followers, such as Clare of Assisi

Clare of Assisi (born Chiara Offreduccio and sometimes spelled Clara, Clair, Claire, Sinclair; 16 July 1194 – 11 August 1253) was an Italian saint and one of the first followers of Francis of Assisi. She founded the Order of Poor Ladies ...

, Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua ( it, Antonio di Padova) or Anthony of Lisbon ( pt, António/Antônio de Lisboa; born Fernando Martins de Bulhões; 15 August 1195 – 13 June 1231) was a Portuguese Catholic priest and friar of the Franciscan Order. He was bo ...

, and Elizabeth of Hungary. Several smaller Protestant Franciscan orders exist as well, notably in the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

and Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

traditions (e.g. the Community of Francis and Clare).

Francis began preaching around 1207 and traveled to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to seek approval from Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

in 1209 to form a new religious order. The original Rule of Saint Francis

Francis of Assisi founded three orders and gave each of them a special rule. Here, only the rule of the first order is discussed, i.e., that of the Order of Friars Minor.

Origin and contents of the rule

Origin

Whether St. Francis wrote several r ...

approved by the Pope did not allow ownership of property, requiring members of the order to beg for food while preaching. The austerity was meant to emulate the life and ministry of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

. Franciscans traveled and preached in the streets, while staying in church properties. Clare of Assisi

Clare of Assisi (born Chiara Offreduccio and sometimes spelled Clara, Clair, Claire, Sinclair; 16 July 1194 – 11 August 1253) was an Italian saint and one of the first followers of Francis of Assisi. She founded the Order of Poor Ladies ...

, under Francis's guidance, founded the Poor Clares

The Poor Clares, officially the Order of Saint Clare ( la, Ordo sanctae Clarae) – originally referred to as the Order of Poor Ladies, and later the Clarisses, the Minoresses, the Franciscan Clarist Order, and the Second Order of Saint Francis ...

(Order of Saint Clare) of the Franciscans.

The extreme poverty required of members was relaxed in the final revision of the Rule in 1223. The degree of observance required of members remained a major source of conflict within the order, resulting in numerous secessions. The Order of Friars Minor, previously known as the "Observant" branch, is one of the three Franciscan First Orders within the Catholic Church, the others being the " Conventuals" (formed 1517) and "Capuchins

Capuchin can refer to:

*Order of Friars Minor Capuchin

The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (; postnominal abbr. O.F.M. Cap.) is a religious order of Franciscan friars within the Catholic Church, one of Three " First Orders" that reformed from t ...

" (1520). The Order of Friars Minor, in its current form, is the result of an amalgamation of several smaller orders completed in 1897 by Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-ol ...

. The latter two, the Capuchin and Conventual, remain distinct religious institute

A religious institute is a type of institute of consecrated life in the Catholic Church whose members take religious vows and lead a life in community with fellow members. Religious institutes are one of the two types of institutes of consecrat ...

s within the Catholic Church, observing the Rule of Saint Francis

Francis of Assisi founded three orders and gave each of them a special rule. Here, only the rule of the first order is discussed, i.e., that of the Order of Friars Minor.

Origin and contents of the rule

Origin

Whether St. Francis wrote several r ...

with different emphases. Conventual Franciscans are sometimes referred to as minorites or greyfriars because of their habit

A habit (or wont as a humorous and formal term) is a routine of behavior that is repeated regularly and tends to occur subconsciously.

. In Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

they are known as Bernardines, after Bernardino of Siena

Bernardino of Siena, OFM (8 September 138020 May 1444), also known as Bernardine, was an Italian priest and Franciscan missionary preacher in Italy. He was a systematizer of Scholastic economics. His preaching, his book burnings, and his " bon ...

, although the term elsewhere refers to Cistercians

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

instead.

Name and demographics

The name of the original order, (Friars Minor, literally 'Order of Lesser Brothers') stems from Francis of Assisi's rejection of extravagance. Francis was the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, but gave up his wealth to pursue his faith more fully. He had cut all ties that remained with his family, and pursued a life living in solidarity with his fellow brothers in Christ. Francis adopted the simple tunic worn by peasants as the

The name of the original order, (Friars Minor, literally 'Order of Lesser Brothers') stems from Francis of Assisi's rejection of extravagance. Francis was the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, but gave up his wealth to pursue his faith more fully. He had cut all ties that remained with his family, and pursued a life living in solidarity with his fellow brothers in Christ. Francis adopted the simple tunic worn by peasants as the religious habit

A religious habit is a distinctive set of religious clothing worn by members of a religious order. Traditionally some plain garb recognizable as a religious habit has also been worn by those leading the religious eremitic and anchoritic life, ...

for his order, and had others who wished to join him do the same. Those who joined him became the original Order of Friars Minor.

First Order

The First Order or the Order of Friars Minor are commonly called simply the Franciscans. This order is amendicant

A mendicant (from la, mendicans, "begging") is one who practices mendicancy, relying chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. In principle, mendicant religious orders own little property, either individually or collectively, and in many inst ...

religious order

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious pract ...

of men, some of whom trace their origin to Francis of Assisi. Their official Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

name is the . Francis thus referred to his followers as "Fraticelli", meaning "Little Brothers". Franciscan brothers are informally called friars or the Minorites.

The modern organization of the Friars Minor comprises three separate families or groups, each considered a religious order in its own right under its own minister General and particular type of governance. They all live according to a body of regulations known as the Rule of Saint Francis.

* The Order of Friars Minor

The Order of Friars Minor (also called the Franciscans, the Franciscan Order, or the Seraphic Order; postnominal abbreviation OFM) is a mendicant Catholic religious order, founded in 1209 by Francis of Assisi. The order adheres to the teachi ...

, also known as the Observants, are most commonly simply called Franciscan friars, official name: Friars Minor (OFM).

* The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin

The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (; postnominal abbr. O.F.M. Cap.) is a religious order of Franciscan friars within the Catholic Church, one of Three " First Orders" that reformed from the Franciscan Friars Minor Observant (OFM Obs., now OFM ...

or simply Capuchins, official name: Friars Minor Capuchin (OFM Cap.).

* The Order of Friars Minor Conventual or simply Minorites, official name: Friars Minor Conventual (OFM Conv.).

Second Order

The Second Order, most commonly calledPoor Clares

The Poor Clares, officially the Order of Saint Clare ( la, Ordo sanctae Clarae) – originally referred to as the Order of Poor Ladies, and later the Clarisses, the Minoresses, the Franciscan Clarist Order, and the Second Order of Saint Francis ...

in English-speaking countries, consists of only one branch of religious sisters. The order is called the Order of St. Clare (OSC), but prior to 1263 they were called "The Poor Ladies", "The Poor Enclosed Nuns", and "The Order of San Damiano".

Third Order

The Franciscan third order, known as the Third Order of Saint Francis, has many men and women members, separated into two main branches: * The Secular Franciscan Order, OFS, originally known as the Brothers and Sisters of Penance or Third Order of Penance, try to live the ideals of the movement in their daily lives outside ofreligious institute

A religious institute is a type of institute of consecrated life in the Catholic Church whose members take religious vows and lead a life in community with fellow members. Religious institutes are one of the two types of institutes of consecrat ...

s.

* Members of the Third Order Regular (TOR) live in religious communities under the traditional religious vows

Religious vows are the public vows made by the members of religious communities pertaining to their conduct, practices, and views.

In the Buddhism tradition, in particular within the Mahayana and Vajrayana tradition, many different kinds of re ...

. They grew out of the Secular Franciscan Order.

The 2013 gave the following figures for the membership of the principal male Franciscan orders:.''Annuario Pontificio 2013'' (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ), p. 1422

* Order of Friars Minor (OFM): 2,212 communities; 14,123 members; 9,735 priests

* Franciscan Order of Friars Minor Conventual (OFM Conv.): 667 communities; 4,289 members; 2,921 priests

* Franciscan Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (OFM Cap.): 1,633 communities; 10,786 members; 7,057 priests

* Third Order Regular of Saint Francis (TOR): 176 communities; 870 members; 576 priests

The coat of arms that is a universal symbol of Franciscan "contains the Tau cross

The tau cross is a T-shaped cross, sometimes with all three ends of the cross expanded. It is called a “tau cross” because it is shaped like the Greek letter tau, which in its upper-case form has the same appearance as Latin letter T.

Anoth ...

, with two crossed arms: Christ’s right hand with the nail wound and Francis’ left hand with the stigmata wound."

History

Beginnings

A sermon Francis heard in 1209 on Mt 10:9 made such an impression on him that he decided to devote himself wholly to a life of apostolic poverty. Clad in a rough garment, barefoot, and, after theEvangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

precept, without staff or scrip, he began to preach repentance.

He was soon joined by a prominent fellow townsman, Bernard of Quintavalle, who contributed all that he had to the work, and by other companions, who are said to have reached the number of eleven within a year. The brothers lived in the deserted leper colony

A leper colony, also known by many other names, is an isolated community for the quarantining and treatment of lepers, people suffering from leprosy. ''M. leprae'', the bacterium responsible for leprosy, is believed to have spread from East Afr ...

of Rivo Torto near Assisi

Assisi (, also , ; from la, Asisium) is a town and '' comune'' of Italy in the Province of Perugia in the Umbria region, on the western flank of Monte Subasio.

It is generally regarded as the birthplace of the Latin poet Propertius, born arou ...

; but they spent much of their time traveling through the mountainous districts of Umbria

it, Umbro (man) it, Umbra (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, ...

, always cheerful and full of songs, yet making a deep impression on their hearers by their earnest exhortations. Their life was extremely ascetic, though such practices were apparently not prescribed by the first rule which Francis gave them (probably as early as 1209) which seems to have been nothing more than a collection of Scriptural passages emphasizing the duty of poverty.

In spite of some similarities between this principle and some of the fundamental ideas of the followers of Peter Waldo

Peter Waldo (; c. 1140 – c. 1205; also ''Valdo'', ''Valdes'', ''Waldes''; , ) was the leader of the Waldensians, a Christian spiritual movement of the Middle Ages.

The tradition that his first name was "Peter" can only be traced back to the f ...

, the brotherhood of Assisi succeeded in gaining the approval of Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

.Chesterton(1924), pp. 107–108 What seems to have impressed first the Bishop of Assisi, Guido, then Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, t ...

Giovanni di San Paolo and finally Innocent himself, was their utter loyalty to the Catholic Church and the clergy. Innocent III was not only the pope reigning during the life of Francis of Assisi, but he was also responsible for helping to construct the church Francis was being called to rebuild. Innocent III and the Fourth Lateran Council helped maintain the church in Europe. Innocent probably saw in them a possible answer to his desire for an orthodox preaching force to counter heresy. Many legends have clustered around the decisive audience of Francis with the pope. The realistic account in Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

, according to which the pope originally sent the shabby saint off to keep swine, and only recognized his real worth by his ready obedience, has, in spite of its improbability, a certain historical interest, since it shows the natural antipathy of the older Benedictine monasticism to the plebeian mendicant orders. The group was tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice i ...

d and Francis was ordained as a deacon, allowing him to proclaim Gospel passages and preach in churches during Mass.Galli(2002), pp. 74–80

Francis's last years

Francis had to suffer from the dissensions just alluded to and the transformation they effected in the original constitution of the brotherhood making it a regular order under strict supervision from Rome. Exasperated by the demands of running a growing and fractious Order, Francis askedPope Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of import ...

for help in 1219. He was assigned Cardinal Ugolino as protector of the Order by the pope. Francis resigned the day-to-day running of the Order into the hands of others but retained the power to shape the Order's legislation, writing a Rule in 1221 which he revised and had approved in 1223. After about 1221, the day-to-day running of the Order was in the hands of Brother Elias of Cortona

Elias of Cortona was born, it is said, at Bevilia near Assisi, ca. 1180; he died at Cortona, 22 April 1253. He was among the first to join St. Francis of Assisi in his newly founded Order of Friars Minor. In 1221, Francis appointed Elias Vicar Ge ...

, an able friar who would be elected as leader of the friars a few years after Francis's death (1232) but who aroused much opposition because of his autocratic leadership style.Robinson, Paschal. "Elias of Cortona." The Catholic EncyclopediaVol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 28 December 2019 He planned and built the

Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi

The Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Basilica di San Francesco d'Assisi; la, Basilica Sancti Francisci Assisiensis) is the mother church of the Roman Catholic Order of Friars Minor Conventual in Assisi, a town in the Umbria region in c ...

in which Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

is buried, a building which includes the friary Sacro Convento, still today the spiritual centre of the Order.

In the external successes of the brothers, as they were reported at the yearly general chapters, there was much to encourage Francis. , the first German provincial, a zealous advocate of the founder's strict principle of poverty, began in 1221 from

In the external successes of the brothers, as they were reported at the yearly general chapters, there was much to encourage Francis. , the first German provincial, a zealous advocate of the founder's strict principle of poverty, began in 1221 from Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

, with twenty-five companions, to win for the Order the land watered by the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

and the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

. In 1224 Agnellus of Pisa led a small group of friars to England. The branch of the Order arriving in England became known as the "greyfriars". Beginning at Greyfriars Greyfriars, Grayfriars or Gray Friars is a term for Franciscan Order of Friars Minor, in particular, the Conventual Franciscans. The term often refers to buildings or districts formerly associated with the order.

Former Friaries

* Greyfriars, Bed ...

at Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of t ...

, the ecclesiastical capital, they moved on to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, the political capital, and Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, the intellectual capital. From these three bases the Franciscans swiftly expanded to embrace the principal towns of England.

Dissensions during Francis's life

The controversy about how to follow the Gospel life of poverty, which extends through the first three centuries of Franciscan history, began in the lifetime of the founder. The ascetic brothers Matthew ofNarni

Narni (in Latin, Narnia) is an ancient hilltown and '' comune'' of Umbria, in central Italy, with 19,252 inhabitants (2017). At an altitude of 240 m (787 ft), it overhangs a narrow gorge of the Nera River in the province of Tern ...

and Gregory of Naples, a nephew of Cardinal Ugolino, were the two vicars-general to whom Francis had entrusted the direction of the order during his absence. They carried through at a chapter which they held certain stricter regulations in regard to fasting and the reception of alms, which departed from the spirit of the original rule. It did not take Francis long, on his return, to suppress this insubordinate tendency but he was less successful in regard to another of an opposite nature which soon came up. Elias of Cortona

Elias of Cortona was born, it is said, at Bevilia near Assisi, ca. 1180; he died at Cortona, 22 April 1253. He was among the first to join St. Francis of Assisi in his newly founded Order of Friars Minor. In 1221, Francis appointed Elias Vicar Ge ...

originated a movement for the increase of the worldly consideration of the Order and the adaptation of its system to the plans of the hierarchy which conflicted with the original notions of the founder and helped to bring about the successive changes in the rule already described. Francis was not alone in opposition to this lax and secularizing tendency. On the contrary, the party which clung to his original views and after his death took his "Testament" for their guide, known as Observantists or , was at least equal in numbers and activity to the followers of Elias.

Custody of the Holy Land

After an intense apostolic activity in Italy, in 1219 Francis went toEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

with the Fifth Crusade to announce the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

to the Saracens

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia ...

. He met with the Sultan Malik al-Kamil

Al-Kamil ( ar, الكامل) (full name: al-Malik al-Kamil Naser ad-Din Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad) (c. 1177 – 6 March 1238) was a Muslim ruler and the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. During his tenure as sultan, the Ayyubids defeated the Fifth Cru ...

, initiating a spirit of dialogue and understanding between Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

and Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. The Franciscan presence in the Holy Land started in 1217, when the province of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

was established, with Brother Elias as Minister. By 1229 the friars had a small house near the fifth station of the Via Dolorosa. In 1272 sultan Baibars

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari ( ar, الملك الظاهر ركن الدين بيبرس البندقداري, ''al-Malik al-Ẓāhir Rukn al-Dīn Baybars al-Bunduqdārī'') (1223/1228 – 1 July 1277), of Turkic Kipchak ...

allowed the Franciscans to settle in the Cenacle

The Cenacle (from the Latin , "dining room"), also known as the Upper Room (from the Koine Greek and , both meaning "upper room"), is a room in Mount Zion in Jerusalem, just outside the Old City walls, traditionally held to be the site o ...

on Mount Zion

Mount Zion ( he, הַר צִיּוֹן, ''Har Ṣīyyōn''; ar, جبل صهيون, ''Jabal Sahyoun'') is a hill in Jerusalem, located just outside the walls of the Old City. The term Mount Zion has been used in the Hebrew Bible first for the Ci ...

. Later on, in 1309, they also settled in the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, hy, Սուրբ Հարության տաճար, la, Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri, am, የቅዱስ መቃብር ቤተክርስቲያን, he, כנסיית הקבר, ar, كنيسة القيامة is a church i ...

and in Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, بيت لحم ; he, בֵּית לֶחֶם '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital ...

. In 1335 the king of Naples Robert of Anjou ( it, Roberto d'Angiò) and his wife Sancha of Majorca

Sancia of Majorca (c. 1281 – 28 July 1345), also known as Sancha, was Queen of Naples from 1309 until 1343 as the wife of Robert the Wise. She served as regent of Naples during the minority of her stepgrandaughter, Joanna I of Naples, from 1343 ...

( it, Sancia di Maiorca) bought the Cenacle and gave it to the Franciscans. Pope Clement VI

Pope Clement VI ( la, Clemens VI; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Bl ...

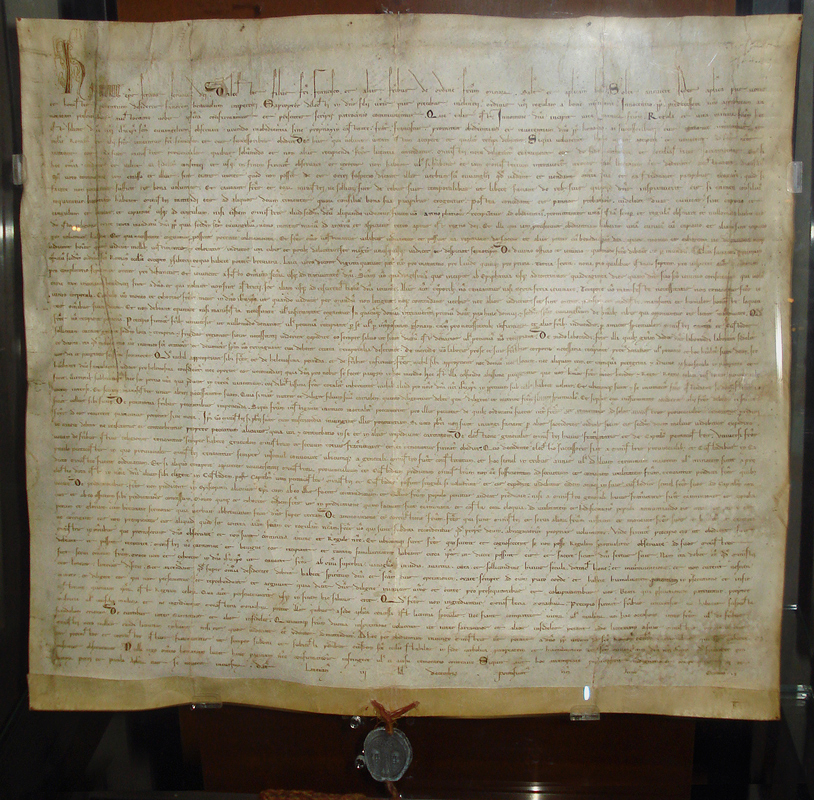

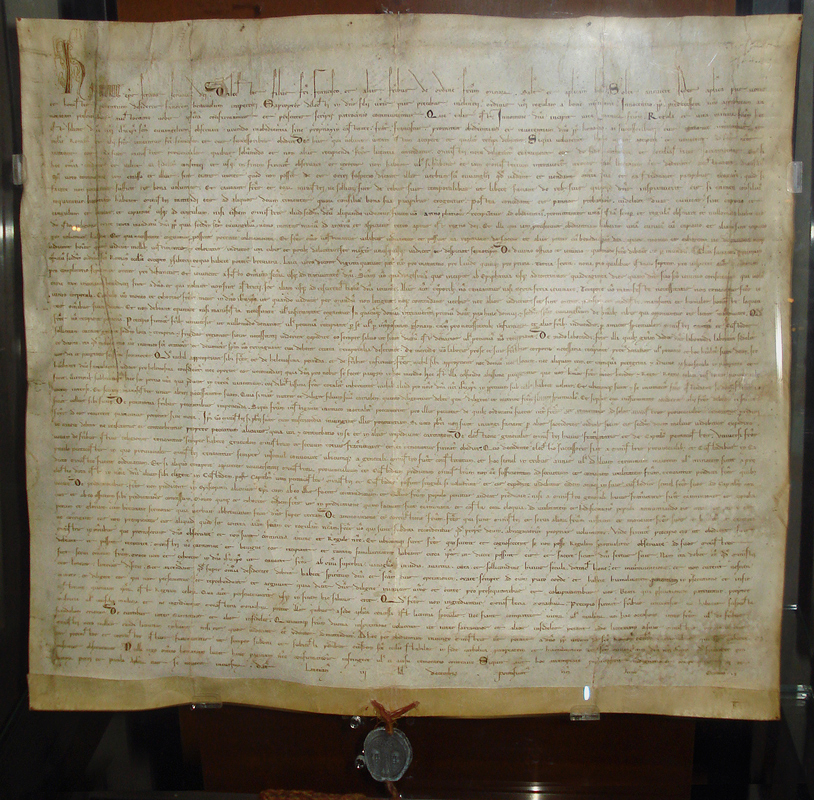

by the Bulls ''Gratias agimus'' and ''Nuper charissimae'' (1342) declared the Franciscans as the official custodians of the Holy Places in the name of the Catholic Church.

The Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land

, native_name_lang = Latin

, named_after=

, image = Coat_of_arms_of_the_Custodian_of_the_Holy_Land.jpg

, image_size = 200px

, alt=

, caption = Coat of arms of the Custody of the Holy Land

, map ...

is still in force today.

Development after Francis's death

Development to 1239

Elias was a lay friar, and encouraged other laymen to enter the order. This brought opposition from many ordained friars and ministers provincial, who also opposed increased centralization of the Order. Gregory IX declared his intention to build a splendid church to house the body of Francis and the task fell to Elias, who at once began to lay plans for the erection of a great basilica at Assisi, to enshrine the remains of the ''Poverello''. In order to build the basilica, Elias proceeded to collect money in various ways to meet the expenses of the building. Elias thus also alienated the zealots in the order, who felt this was not in keeping with the founder's views upon the question of poverty.

The earliest leader of the strict party was

Elias was a lay friar, and encouraged other laymen to enter the order. This brought opposition from many ordained friars and ministers provincial, who also opposed increased centralization of the Order. Gregory IX declared his intention to build a splendid church to house the body of Francis and the task fell to Elias, who at once began to lay plans for the erection of a great basilica at Assisi, to enshrine the remains of the ''Poverello''. In order to build the basilica, Elias proceeded to collect money in various ways to meet the expenses of the building. Elias thus also alienated the zealots in the order, who felt this was not in keeping with the founder's views upon the question of poverty.

The earliest leader of the strict party was Brother Leo

Brother Leo (died c. 1270) was the favorite disciple, secretary and confessor of St Francis of Assisi. The dates of his birth and of his becoming a Franciscan are not known; a native of Assisi, he was one of the small group of most trusted compa ...

, a close companion of Francis during his last years and the author of the , a strong polemic against the laxer party. Having protested against the collection of money for the erection of the basilica of San Francesco, it was Leo who broke in pieces the marble box which Elias had set up for offertories for the completion of the basilica at Assisi

Assisi (, also , ; from la, Asisium) is a town and '' comune'' of Italy in the Province of Perugia in the Umbria region, on the western flank of Monte Subasio.

It is generally regarded as the birthplace of the Latin poet Propertius, born arou ...

. For this Elias had him scourged, and this outrage on St Francis's dearest disciple consolidated the opposition to Elias. Leo was the leader in the early stages of the struggle in the order for the maintenance of St Francis's ideas on strict poverty.Robinson, Paschal. "Brother Leo." The Catholic EncyclopediaVol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 28 December 2019 At the chapter held in May 1227, Elias was rejected in spite of his prominence, and Giovanni Parenti, Minister Provincial of Spain, was elected Minister General of the order. In 1232 Elias succeeded him, and under him the Order significantly developed its ministries and presence in the towns. Many new houses were founded, especially in Italy, and in many of them special attention was paid to education. The somewhat earlier settlements of Franciscan teachers at the universities (in

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, for example, where Alexander of Hales

Alexander of Hales (also Halensis, Alensis, Halesius, Alesius ; 21 August 1245), also called ''Doctor Irrefragibilis'' (by Pope Alexander IV in the ''Bull De Fontibus Paradisi'') and ''Theologorum Monarcha'', was a Franciscan friar, theologian a ...

was teaching) continued to develop. Contributions toward the promotion of the Order's work, and especially the building of the Basilica in Assisi, came in abundantly. Funds could only be accepted on behalf of the friars for determined, imminent, real necessities that could not be provided for from begging. When in 1230, the General Chapter could not agree on a common interpretation of the 1223 Rule it sent a delegation including Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua ( it, Antonio di Padova) or Anthony of Lisbon ( pt, António/Antônio de Lisboa; born Fernando Martins de Bulhões; 15 August 1195 – 13 June 1231) was a Portuguese Catholic priest and friar of the Franciscan Order. He was bo ...

to Pope Gregory IX for an authentic interpretation of this piece of papal legislation. The bull of Gregory IX declared that the Testament of St. Francis was not legally binding and offered an interpretation of poverty that would allow the Order to continue to develop. Gregory IX, authorized agents of the Order to have custody of such funds where they could not be spent immediately. Elias pursued with great severity the principal leaders of the opposition, and even Bernardo di Quintavalle, the founder's first disciple, was obliged to conceal himself for years in the forest of Monte Sefro.

The conflict between the two parties lasted many years and the won several notable victories in spite of the favor shown to their opponents by the papal administration, until finally the reconciliation of the two points of view was seen to be impossible and the order was actually split into halves.

1239–1274

Elias governed the Order from the center, imposing his authority on the provinces (as had Francis). A reaction to this centralized government was led from the provinces of England and Germany. At the general chapter of 1239, held in Rome under the personal presidency of Gregory IX, Elias was deposed in favor of Albert of Pisa, the former provincial of England, a moderate Observantist. This chapter introduced General Statutes to govern the Order and devolved power from the

Elias governed the Order from the center, imposing his authority on the provinces (as had Francis). A reaction to this centralized government was led from the provinces of England and Germany. At the general chapter of 1239, held in Rome under the personal presidency of Gregory IX, Elias was deposed in favor of Albert of Pisa, the former provincial of England, a moderate Observantist. This chapter introduced General Statutes to govern the Order and devolved power from the Minister General

Minister General is the term used for the leader or Superior General of the different branches of the Order of Friars Minor. It is a term exclusive to them, and comes directly from its founder, St. Francis of Assisi. He chose this word over "Sup ...

to the Ministers Provincial sitting in chapter. The next two Ministers General, Haymo of Faversham

Haymo of Faversham, O.F.M. ( ) was an English Franciscan scholar. His scholastic epithet was ' (Latin for "Most Aristotelian among the Aristotelians"), referring to his stature among the Scholastics during the Recovery of Aristotle amid the ...

(1240–44) and Crescentius of Jesi (1244–47), consolidated this greater democracy in the Order but also led the Order towards a greater clericalization. The new Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV ( la, Innocentius IV; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universitie ...

supported them in this. In a bull of November 14, 1245, this pope even sanctioned an extension of the system of financial agents, and allowed the funds to be used not simply for those things that were necessary for the friars but also for those that were useful.

The Observantist party took a strong stand in opposition to this ruling and agitated so successfully against the lax General that in 1247, at a chapter held in Lyon, France—where Innocent IV was then residing—he was replaced by the strict Observantist John of Parma (1247–57) and the Order refused to implement any provisions of Innocent IV that were laxer than those of Gregory IX.

Elias, who had been excommunicated and taken under the protection of Frederick II, was now forced to give up all hope of recovering his power in the Order. He died in 1253, after succeeding by recantation in obtaining the removal of his censures. Under John of Parma, who enjoyed the favor of Innocent IV and

Elias, who had been excommunicated and taken under the protection of Frederick II, was now forced to give up all hope of recovering his power in the Order. He died in 1253, after succeeding by recantation in obtaining the removal of his censures. Under John of Parma, who enjoyed the favor of Innocent IV and Pope Alexander IV

Pope Alexander IV (1199 or 1185 – 25 May 1261) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 December 1254 to his death in 1261.

Early career

He was born as Rinaldo di Jenne in Jenne (now in the Province of Rome), he ...

, the influence of the Order was notably increased, especially by the provisions of the latter pope in regard to the academic activity of the brothers. He not only sanctioned the theological institutes in Franciscan houses, but did all he could to support the friars in the Mendicant Controversy, when the secular Masters of the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

and the Bishops of France combined to attack the mendicant orders. It was due to the action of Alexander IV's envoys, who were obliged to threaten the university authorities with excommunication, that the degree of doctor of theology was finally conceded to the Dominican Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

and the Franciscan Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; it, Bonaventura ; la, Bonaventura de Balneoregio; 1221 – 15 July 1274), born Giovanni di Fidanza, was an Italian Catholic Franciscan, bishop, cardinal, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister G ...

(1257), who had previously been able to lecture only as licentiates.

The Franciscan Gerard of Borgo San Donnino at this time issued a Joachimite tract and John of Parma was seen as favoring the condemned theology of Joachim of Fiore. To protect the Order from its enemies, John was forced to step down and recommended Bonaventure as his successor. Bonaventure saw the need to unify the Order around a common ideology and both wrote a new life of the founder and collected the Order's legislation into the Constitutions of Narbonne, so called because they were ratified by the Order at its chapter held at Narbonne

Narbonne (, also , ; oc, Narbona ; la, Narbo ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the ...

, France, in 1260. In the chapter of Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ci ...

three years later Bonaventure's was approved as the only biography of Francis and all previous biographies were ordered to be destroyed. Bonaventure ruled (1257–74) in a moderate spirit, which is represented also by various works produced by the order in his time—especially by the written by David of Augsburg soon after 1260.

14th century

1274–1300

The successor to Bonaventure, Jerome of Ascoli or Girolamo Masci (1274–79), (the future Pope Nicholas IV), and his successor, Bonagratia of Bologna (1279–85), also followed a middle course. Severe measures were taken against certain extremeSpirituals

Spirituals (also known as Negro spirituals, African American spirituals, Black spirituals, or spiritual music) is a genre of Christian music that is associated with Black Americans, which merged sub-Saharan African cultural heritage with the ex ...

who, on the strength of the rumor that Pope Gregory X was intending at the Council of Lyon The Council of Lyon may refer to a number of synods or councils of the Roman Catholic Church, held in Lyon, France or in nearby Anse.

Previous to 1313, a certain Abbé Martin counted twenty-eight synods or councils held at Lyons

or at Anse.

Some ...

(1274–75) to force the mendicant orders to tolerate the possession of property, threatened both pope and council with the renunciation of allegiance. Attempts were made, however, to satisfy the reasonable demands of the Spiritual party, as in the bull ''Exiit qui seminat'' of Pope Nicholas III (1279), which pronounced the principle of complete poverty to be meritorious and holy, but interpreted it in the way of a somewhat sophistical distinction between possession and usufruct. The bull was received respectfully by Bonagratia and the next two generals, Arlotto of Prato (1285–87) and Matthew of Aqua Sparta (1287–89); but the Spiritual party under the leadership of the Bonaventuran pupil and apocalyptic Pierre Jean Olivi Peter John Olivi, also Pierre de Jean Olivi or Petrus Joannis Olivi (1248 – 14 March 1298), was a French Franciscan theologian and philosopher who, although he died professing the faith of the Roman Catholic Church, remained a controversial figure ...

regarded its provisions for the dependence of the friars upon the pope and the division between brothers occupied in manual labor and those employed on spiritual missions as a corruption of the fundamental principles of the Order. They were not won over by the conciliatory attitude of the next general, Raymond Gaufredi (1289–96), and of the Franciscan Pope Nicholas IV (1288–92). The attempt made by the next pope, Celestine V, an old friend of the order, to end the strife by uniting the Observantist party with his own order of hermits (see Celestines) was scarcely more successful. Only a part of the Spirituals joined the new order, and the secession scarcely lasted beyond the reign of the hermit-pope. Pope Boniface VIII annulled Celestine's bull of foundation with his other acts, deposed the general Raymond Gaufredi, and appointed a man of laxer tendency, John de Murro, in his place. The Benedictine section of the Celestines was separated from the Franciscan section, and the latter was formally suppressed by Pope Boniface VIII in 1302. The leader of the Observantists, Olivi, who spent his last years in the Franciscan house at Tarnius and died there in 1298, had pronounced against the extremer "Spiritual" attitude, and given an exposition of the theory of poverty which was approved by the more moderate Observantists, and for a long time constituted their principle.

Persecution

UnderPope Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

(1305–14) this party succeeded in exercising some influence on papal decisions. In 1309 Clement had a commission sit at Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

for the purpose of reconciling the conflicting parties. Ubertino of Casale, the leader, after Olivi's death, of the stricter party, who was a member of the commission, induced the Council of Vienne to arrive at a decision in the main favoring his views, and the papal constitution (1313) was on the whole conceived in the same sense. Clement's successor, Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected b ...

(1316–34), favored the laxer or conventual party. By the bull he modified several provisions of the constitution , and required the formal submission of the Spirituals. Some of them, encouraged by the strongly Observantist general Michael of Cesena, ventured to dispute the pope's right so to deal with the provisions of his predecessor. Sixty-four of them were summoned to Avignon and the most obstinate delivered over to the Inquisition, four of them being burned (1318). Shortly before this all the separate houses of the Observantists had been suppressed.

Renewed controversy on the question of poverty

A few years later a new controversy, this time theoretical, broke out on the question of

A few years later a new controversy, this time theoretical, broke out on the question of poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse

. In his 14 August 1279 bull , Pope Nicholas III

Pope Nicholas III ( la, Nicolaus III; c. 1225 – 22 August 1280), born Giovanni Gaetano Orsini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 November 1277 to his death on 22 August 1280.

He was a Roman nobleman who ...

had confirmed the arrangement already established by Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV ( la, Innocentius IV; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universitie ...

, by which all property given to the Franciscans was vested in the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

, which granted the friars the mere use of it. The bull declared that renunciation of ownership of all things "both individually but also in common, for God's sake, is meritorious and holy; Christ, also, showing the way of perfection, taught it by word and confirmed it by example, and the first founders of the church militant, as they had drawn it from the fountainhead itself, distributed it through the channels of their teaching and life to those wishing to live perfectly."

Although ''Exiit qui seminat'' banned disputing about its contents, the decades that followed saw increasingly bitter disputes about the form of poverty to be observed by Franciscans, with the Spirituals (so called because associated with the Age of the Spirit that Joachim of Fiore had said would begin in 1260) pitched against the Conventual Franciscans

The Order of Friars Minor Conventual (OFM Conv) is a male religious fraternity in the Roman Catholic Church that is a branch of the Franciscans. The friars in OFM CONV are also known as Conventual Franciscans, or Minorites.

Dating back to ...

. Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

's bull of 20 November 1312 failed to effect a compromise between the two factions. Clement V's successor, Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected b ...

was determined to suppress what he considered to be the excesses of the Spirituals, who contended eagerly for the view that Christ and his apostles had possessed absolutely nothing, either separately or jointly, and who were citing in support of their view. In 1317, John XXII formally condemned the group of them known as the Fraticelli. On 26 March 1322, with , he removed the ban on discussion of Nicholas III's bull and commissioned experts to examine the idea of poverty based on belief that Christ and the apostles owned nothing. The experts disagreed among themselves, but the majority condemned the idea on the grounds that it would condemn the church's right to have possessions. The Franciscan chapter held in Perugia

Perugia (, , ; lat, Perusia) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber, and of the province of Perugia.

The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part ...

in May 1322 declared on the contrary: "To say or assert that Christ, in showing the way of perfection, and the Apostles, in following that way and setting an example to others who wished to lead the perfect life, possessed nothing either severally or in common, either by right of ownership and or by personal right, we corporately and unanimously declare to be not heretical, but true and catholic." By the bull of 8 December 1322, John XXII, declaring it ridiculous to pretend that every scrap of food given to the friars and eaten by them belonged to the pope, refused to accept ownership over the goods of the Franciscans in the future and granted them exemption from the rule that absolutely forbade ownership of anything even in common, thus forcing them to accept ownership. And, on 12 November 1323, he issued the short bull which declared "erroneous and heretical" the doctrine that Christ and his apostles had no possessions whatever. John XXII's actions thus demolished the fictitious structure that gave the appearance of absolute poverty to the life of the Franciscan friars.

Influential members of the order protested, such as the minister general Michael of Cesena, the English provincial William of Ockham

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vil ...

, and Bonagratia of Bergamo. In 1324, Louis the Bavarian sided with the Spirituals and accused the pope of heresy. In reply to the argument of his opponents that Nicholas III's bull was fixed and irrevocable, John XXII issued the bull on 10 November 1324 in which he declared that it cannot be inferred from the words of the 1279 bull that Christ and the apostles had nothing, adding: "Indeed, it can be inferred rather that the Gospel life lived by Christ and the Apostles did not exclude some possessions in common, since living 'without property' does not require that those living thus should have nothing in common." In 1328, Michael of Cesena was summoned to Avignon to explain the Order's intransigence in refusing the pope's orders and its complicity with Louis of Bavaria. Michael was imprisoned in Avignon, together with Francesco d'Ascoli, Bonagratia, and William of Ockham. In January of that year Louis of Bavaria entered Rome and had himself crowned emperor. Three months later he declared John XXII deposed and installed the Spiritual Franciscan Pietro Rainalducci as antipope

An antipope ( la, antipapa) is a person who makes a significant and substantial attempt to occupy the position of Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. At times between the 3rd and mi ...

. The Franciscan chapter that opened in Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different na ...

on 28 May reelected Michael of Cesena, who two days before had escaped with his companions from Avignon. But in August Louis the Bavarian and his pope had to flee Rome before an attack by Robert, King of Naples

Robert of Anjou ( it, Roberto d'Angiò), known as Robert the Wise ( it, Roberto il Saggio; 1276 – 20 January 1343), was King of Naples, titular King of Jerusalem and Count of Provence and Forcalquier from 1309 to 1343, the central figure of ...

. Only a small part of the Franciscan Order joined the opponents of John XXII, and at a general chapter held in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in 1329 the majority of all the houses declared their submission to the Pope. With the bull of 16 November 1329, John XXII replied to Michael of Cesena's attacks on , , and . In 1330, Antipope Nicholas V submitted, followed later by the ex-general Michael, and finally, just before his death, by Ockham.

Separate congregations

Out of all these dissensions in the 14th century sprang a number of separate congregations, or almost sects, to say nothing of the heretical parties of the Beghards andFraticelli

The Fraticelli (Italian for "Little Brethren") or Spiritual Franciscans opposed changes to the rule of Saint Francis of Assisi, especially with regard to poverty, and regarded the wealth of the Church as scandalous, and that of individual church ...

, some of which developed within the Order on both hermit and cenobitic principles and may here be mentioned:

Clareni

The Clareni or Clarenini was an association of hermits established on the river Clareno in the march ofAncona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

by Angelo da Clareno (1337). Like several other smaller congregations, it was obliged in 1568 under Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

to unite with the general body of Observantists.

Minorites of Narbonne

As a separate congregation, this originated through the union of a number of houses which followed Olivi after 1308. It was limited to southwestern France and, its members being accused of the heresy of the Beghards, was suppressed by the Inquisition during the controversies under John XXII.Reform of Johannes de Vallibus

Foligno

Foligno (; Southern Umbrian: ''Fuligno'') is an ancient town of Italy in the province of Perugia in east central Umbria, on the Topino river where it leaves the Apennines and enters the wide plain of the Clitunno river system. It is located sou ...

in 1334. The congregation was suppressed by the Franciscan general chapter in 1354; reestablished in 1368 by Paolo de' Trinci of Foligno; confirmed by Gregory XI in 1373, and spread rapidly from Central Italy to France, Spain, Hungary, and elsewhere. Most of the Observantist houses joined this congregation by degrees, so that it became known simply as the "brothers of the regular Observance." It acquired the favor of the popes by its energetic opposition to the heretical Fraticelli

The Fraticelli (Italian for "Little Brethren") or Spiritual Franciscans opposed changes to the rule of Saint Francis of Assisi, especially with regard to poverty, and regarded the wealth of the Church as scandalous, and that of individual church ...

, and was expressly recognized by the Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the r ...

(1415). It was allowed to have a special vicar-general of its own and legislate for its members without reference to the conventual part of the Order. Through the work of such men as Bernardino of Siena

Bernardino of Siena, OFM (8 September 138020 May 1444), also known as Bernardine, was an Italian priest and Franciscan missionary preacher in Italy. He was a systematizer of Scholastic economics. His preaching, his book burnings, and his " bon ...

, Giovanni da Capistrano, and Dietrich Coelde (b. 1435? at Munster; was a member of the Brethren of the Common Life, died December 11, 1515), it gained great prominence during the 15th century. By the end of the Middle Ages, the Observantists, with 1,400 houses, comprised nearly half of the entire Order. Their influence brought about attempts at reform even among the Conventuals, including the quasi-Observantist brothers living under the rule of the Conventual ministers (Martinianists or ''Observantes sub ministris''), such as the male Colletans, later led by Boniface de Ceva in his reform attempts principally in France and Germany; the reformed congregation founded in 1426 by the Spaniard Philip de Berbegal and distinguished by the special importance they attached to the little hood (); the Neutri, a group of reformers originating about 1463 in Italy, who tried to take a middle ground between the Conventuals and Observantists, but refused to obey the heads of either, until they were compelled by the pope to affiliate with the regular Observantists, or with those of the Common Life; the Caperolani, a congregation founded about 1470 in North Italy by Peter Caperolo, but dissolved again on the death of its founder in 1481; the Amadeists, founded by the noble Portuguese Amadeo, who entered the Franciscan order at Assisi in 1452, gathered around him a number of adherents to his fairly strict principles (numbering finally twenty-six houses), and died in the odor of sanctity in 1482.

Unification

Projects for a union between the two main branches of the Order were put forth not only by the Council of Constance but by several popes, without any positive result. By direction of

Projects for a union between the two main branches of the Order were put forth not only by the Council of Constance but by several popes, without any positive result. By direction of Pope Martin V

Pope Martin V ( la, Martinus V; it, Martino V; January/February 1369 – 20 February 1431), born Otto (or Oddone) Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. Hi ...

, John of Capistrano drew up statutes which were to serve as a basis for reunion, and they were actually accepted by a general chapter at Assisi in 1430; but the majority of the Conventual houses refused to agree to them, and they remained without effect. At John of Capistrano's request Eugene IV

Pope Eugene IV ( la, Eugenius IV; it, Eugenio IV; 1383 – 23 February 1447), born Gabriele Condulmer, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 3 March 1431 to his death in February 1447. Condulmer was a Venetian, and ...

issued a bull (, 1446) aimed at the same result, but again nothing was accomplished. Equally unsuccessful were the attempts of the Franciscan Pope Sixtus IV

Pope Sixtus IV ( it, Sisto IV: 21 July 1414 – 12 August 1484), born Francesco della Rovere, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 August 1471 to his death in August 1484. His accomplishments as pope include ...

, who bestowed a vast number of privileges on both of the original mendicant orders, but by this very fact lost the favor of the Observants and failed in his plans for reunion. Julius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or the ...

succeeded in reducing some of the smaller branches, but left the division of the two great parties untouched. This division was finally legalized by Leo X, after a general chapter held in Rome in 1517, in connection with the reform-movement of the Fifth Lateran Council

The Fifth Council of the Lateran, held between 1512 and 1517, was the eighteenth ecumenical council of the Catholic Church and was the last council before the Protestant Reformation and the Council of Trent. It was convoked by Pope Julius II to ...

, had once more declared the impossibility of reunion. The less strict principles of the Conventuals, permitting the possession of real estate and the enjoyment of fixed revenues, were recognized as tolerable, while the Observants, in contrast to this , were held strictly to their own or ''pauper''.

All of the groups that followed the Franciscan Rule literally were united to the Observants, and the right to elect the Minister General of the Order, together with the seal of the Order, was given to this united grouping. This grouping, since it adhered more closely to the rule of the founder, was allowed to claim a certain superiority over the Conventuals. The Observant general (elected now for six years, not for life) inherited the title of "Minister-General of the Whole Order of St. Francis" and was granted the right to confirm the choice of a head for the Conventuals, who was known as "Master-General of the Friars Minor Conventual"—although this privilege never became practically operative.

=New World missions

= .

The work of the Franciscans in New Spain began in 1523, when three Flemish friars—Juan de Ayora, Pedro de Tecto, and Pedro de Gante—reached the central highlands. Their impact as missionaries was limited at first, since two of them died on Cortés's expedition to Central American in 1524, but Fray Pedro de Gante initiated the evangelization process and studied the

.

The work of the Franciscans in New Spain began in 1523, when three Flemish friars—Juan de Ayora, Pedro de Tecto, and Pedro de Gante—reached the central highlands. Their impact as missionaries was limited at first, since two of them died on Cortés's expedition to Central American in 1524, but Fray Pedro de Gante initiated the evangelization process and studied the Nahuatl language

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

through his contacts with children of the Indian elite from the city of Tetzcoco. Later, in May 1524, with the arrival of the Twelve Apostles of Mexico, led by Martín de Valencia. There they built the Convento Grande de San Francisco, which became Franciscan headquarters for New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the A ...

for the next three hundred years.

Franciscans and the Inquisition

About 1236, Pope Gregory IX appointed the Franciscans, along with the Dominicans, as Inquisitors. The Franciscans had been involved in anti-heretical activities from the beginning simply by preaching and acting as living examples of the Gospel life. As official Inquisitors, they were authorized to use torture to extract confessions, as approved by Pope Innocent IV in 1252. The Franciscans were involved in the torture and trials of heretics and witches throughout the Middle Ages and wrote their own manuals to guide Inquisitors, such as the 14th century ''Codex Casanatensis'' for use by Inquisitors in Tuscany.Contemporary organizations

First Order

Order of Friars Minor

The

The Order of Friars Minor

The Order of Friars Minor (also called the Franciscans, the Franciscan Order, or the Seraphic Order; postnominal abbreviation OFM) is a mendicant Catholic religious order, founded in 1209 by Francis of Assisi. The order adheres to the teachi ...

(OFM) has 1,500 houses in about 100 provinces and , with about 16,000 members. In 1897, Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-ol ...

combined the Observants, Discalced (Alcantarines), Recollects, and Riformati into one order under general constitutions. While the Capuchins and Conventuals wanted the reunited Observants to be referred to as The Order of Friars Minor of the Leonine Union, they were instead called simply the Order of Friars Minor

The Order of Friars Minor (also called the Franciscans, the Franciscan Order, or the Seraphic Order; postnominal abbreviation OFM) is a mendicant Catholic religious order, founded in 1209 by Francis of Assisi. The order adheres to the teachi ...

. Despite the tensions caused by this forced union the Order grew from 1897 to reach a peak of 26,000 members in the 1960s before declining after the 1970s. The Order is headed by a Minister General, who since May 2013 is Father Michael Anthony Perry.

Order of Friars Minor Conventual

The Order of Friars Minor Conventual (OFM Conv.) consists of 290 houses worldwide with a total of almost 5000 friars. They have experienced growth in this century throughout the world. They are located in Italy, the United States, Canada, Australia, and throughout Latin America, and Africa. They are the largest in number in Poland because of the work and inspiration ofMaximilian Kolbe