Francis Legatt Chantrey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey (7 April 1781 – 25 November 1841) was an English sculptor. He became the leading portrait sculptor in

Chantrey developed a procedure of making a portrait sculpture in which he would begin by making two life-sized drawings of his sitter's head, one full-face and one in profile, with the aid of a ''

Chantrey developed a procedure of making a portrait sculpture in which he would begin by making two life-sized drawings of his sitter's head, one full-face and one in profile, with the aid of a ''

Chantrey was a prolific sculptor. According to an article published in 1842, he produced, besides his busts and reliefs, three equestrian statues, 18 standing ones, 18 seated ones and 14 recumbent figures. His most notable works include the statues of

Chantrey was a prolific sculptor. According to an article published in 1842, he produced, besides his busts and reliefs, three equestrian statues, 18 standing ones, 18 seated ones and 14 recumbent figures. His most notable works include the statues of  He executed four monuments to military heroes for

He executed four monuments to military heroes for

By his will, dated 31 December 1840, Chantrey (who had no children) left his whole residuary personal estate after the decease or on the second marriage of his widow (less certain specified annuities and bequests) in trust for the president and trustees of the Royal Academy (or in the event of its dissolution to such society as might take its place), the income to be devoted to the encouragement of British painting and sculpture, by "the purchase of works of fine art of the highest merit ... that can be obtained." The funds might be allowed to accumulate for not more than five years; works by British or foreign artists, dead or living, might be acquired, so long as such works were entirely executed within Great Britain, the artists having been in residence there during the execution and completion. The prices to be paid were to be "liberal," and no sympathy for an artist or his family was to influence the selection or the purchase of works, which were to be acquired solely on the ground of intrinsic merit. No commission or orders might be given: the works must be finished before purchase. Conditions were made as to the exhibition of the works, in the confident expectation that the government or the country would provide a suitable gallery for their display; and an annual sum of £300 and £50 was to be paid to the president and the secretary of the

By his will, dated 31 December 1840, Chantrey (who had no children) left his whole residuary personal estate after the decease or on the second marriage of his widow (less certain specified annuities and bequests) in trust for the president and trustees of the Royal Academy (or in the event of its dissolution to such society as might take its place), the income to be devoted to the encouragement of British painting and sculpture, by "the purchase of works of fine art of the highest merit ... that can be obtained." The funds might be allowed to accumulate for not more than five years; works by British or foreign artists, dead or living, might be acquired, so long as such works were entirely executed within Great Britain, the artists having been in residence there during the execution and completion. The prices to be paid were to be "liberal," and no sympathy for an artist or his family was to influence the selection or the purchase of works, which were to be acquired solely on the ground of intrinsic merit. No commission or orders might be given: the works must be finished before purchase. Conditions were made as to the exhibition of the works, in the confident expectation that the government or the country would provide a suitable gallery for their display; and an annual sum of £300 and £50 was to be paid to the president and the secretary of the  Lady Chantrey died in 1875 and was buried with

Lady Chantrey died in 1875 and was buried with

Works by Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey

at the

Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections

* , an image drawn by Henry Corbould and accompanied by

Regency era

The Regency era of British history is commonly understood as the years between and 1837, although the official regency for which it is named only spanned the years 1811 to 1820. King George III first suffered debilitating illness in the lat ...

Britain, producing busts and statues of many notable figures of the time. Chantrey's most notable works include the statues of King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

(Trafalgar Square); King George III (Guildhall), and George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

(Massachusetts State House). He also executed four monuments to military heroes for St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. He left the ''Chantrey Bequest'' (or ''Chantrey Fund'') for the purchase of works of art for the nation, which was available from 1878 after the death of his widow.

Life

Chantrey was born at Jordanthorpe near Norton (then aDerbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

village, now a suburb of Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

), where his family had a small farm.

His father, who also dabbled in carpentry and wood-carving, died when Francis was twelve; and his mother remarried, leaving him without a clear career to follow. At fifteen, he was working for a grocer in Sheffield, when, having seen some wood-carving in a shop-window, he asked to be apprenticed as a carver instead, and was placed with a woodcarver and gilder called Ramsay in Sheffield.

At Ramsay's house he met the draughtsman and engraver John Raphael Smith who recognised his artistic potential and gave him lessons in painting, and was later to help advance his career by introducing him to potential patrons.

In 1802, Chantrey paid £50 to buy himself out of his apprenticeship with Ramsay and immediately set up a studio as a portrait artist in Sheffield, which allowed him a reasonable income.

For several years he divided his time between Sheffield and London, studying intermittently at the Royal Academy Schools

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

. In the summer of 1802, he travelled to Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, where he fell very ill, losing all his hair. He exhibited pictures at the Royal Academy for a few years from 1804, but from 1807 onwards devoted himself mainly to sculpture.

Asked later in life, as a witness in a court case, whether he had ever worked for any other sculptors, he replied: "No, and what is more, I never had an hour's instruction from any sculptor in my life".

His first recorded marble bust was one of the Rev. James Wilkinson (1805–06), for Sheffield parish church. His first imaginative sculpture, a head of Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

was shown at the Royal Academy in 1808.

In 1809, the architect Daniel Asher Alexander commissioned him to make four monumental plaster busts of the admirals Adam Duncan, 1st Viscount Duncan, Richard Howe, Earl Howe, John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent

John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent ( ; 9 January 1735 – 13 March 1823) was a British Royal Navy admiral and politician. He served throughout the latter half of the 18th century and into the 19th, and was an active commander during the Seven ...

and Horatio Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

for the Royal Naval Asylum at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

, for which he received £10 each. Three of them were shown at the Royal Academy that year.

On 23 November 1809, he married his cousin, Mary Ann Wale at St Mary's Church, Twickenham. By this time he was settled permanently in London,Whinney 1971, p. 147 His wife brought £10,000 into the marriage, which allowed Chantrey to pay off his debts,Jones 1849, p. 9 and for the couple to move into a house at 13 Eccleston Street, Pimlico

Pimlico () is a district in Central London, in the City of Westminster, built as a southern extension to neighbouring Belgravia. It is known for its garden squares and distinctive Regency architecture. Pimlico is demarcated to the north by Lon ...

, (recorded as Chantrey's address in the Royal Academy catalogues from 1810). He also bought land to build two more houses, a studio and offices. In 1811, he showed six busts in the Royal Academy.

The subjects included John Horne Tooke

John Horne Tooke (25 June 1736 – 18 March 1812), known as John Horne until 1782 when he added the surname of his friend William Tooke to his own, was an English clergyman, politician and Philology, philologist. Associated with radical proponen ...

and Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartism, Chartists) of univ ...

, two political figures he greatly admired; his early mentor John Raphael Smith, and Benjamin West

Benjamin West (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as ''The Death of Nelson (West painting), The Death of Nelson'', ''The Death of General Wolfe'', the ''Treaty of Paris ( ...

. Joseph Nollekens placed the bust of Tooke between two of his own, and the prominence given to it is said to have had a significant influence on Chantrey's career. In the wake of the exhibition he received commissions amounting to £12,000. In 1813 he was able to raise his price for a bust to a hundred and fifty guineas, and in 1822 to two hundred.

He visited Paris in 1814, and again in 1815, this time with his wife, Thomas Stothard, and D. A. Alexander, visiting the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

where he especially admired the works of Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), now generally known in English as Raphael ( , ), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. List of paintings by Raphael, His work is admired for its cl ...

and Titian

Tiziano Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian Renaissance painter, the most important artist of Renaissance Venetian painting. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno.

Ti ...

. In 1819 he went to Italy, accompanied by the painter John Jackson, and an old friend named Read. In Rome he met Bertel Thorvaldsen

Albert Bertel Thorvaldsen (; sometimes given as Thorwaldsen; 19 November 1770 – 24 March 1844) was a Danes, Danish-Icelanders, Icelandic Sculpture, sculptor and medallist, medalist of international fame, who spent most of his life (1797–183 ...

and Antonio Canova

Antonio Canova (; 1 November 1757 – 13 October 1822) was an Italians, Italian Neoclassical sculpture, Neoclassical sculptor, famous for his marble sculptures. Often regarded as the greatest of the Neoclassical artists,. his sculpture was ins ...

, getting to know the latter especially well.

In 1828 Chantrey set up his own foundry in Eccleston Place, not far from his house and studio, where large-scale works in bronze, including equestrian statues, could be cast.

Working practices

Chantrey developed a procedure of making a portrait sculpture in which he would begin by making two life-sized drawings of his sitter's head, one full-face and one in profile, with the aid of a ''

Chantrey developed a procedure of making a portrait sculpture in which he would begin by making two life-sized drawings of his sitter's head, one full-face and one in profile, with the aid of a ''camera lucida

A ''camera lucida'' is an optical device used as a drawing aid by artists and microscopy, microscopists. It projects an optics, optical superimposition of the subject being viewed onto the surface upon which the artist is drawing. The artist se ...

''. His assistants would then make a clay model based on the drawings, to which Chantrey would add the finishing touches in front of the sitter. A plaster cast

A plaster cast is a copy made in plaster of another 3-dimensional form. The original from which the cast is taken may be a sculpture, building, a face, a pregnant belly, a fossil or other remains such as fresh or fossilised footprints – ...

would be made of the clay model, and then a marble replica made of that. Allan Cunningham and Henry Weekes were his chief assistants, and made many of the works produced under Chantrey's name. The debilitating effects of heart disease made him even more reliant on assistants in the last few years of his life.

Style

Chantrey was rare among the leading sculptors of his time in not having visited Italy at a formative stage in his career. A writer in Blackwood's '' Edinburgh Magazine'' in 1820 saw him as liberating English sculpture from foreign influence:Those who wish to trace the return of English sculpture from the foreign artificial and allegorical style, to its natural and original character—from cold and conceited fiction to tender and elevated truth, will find it chiefly in the history of Francis Chantrey and his productions.More recently, Margaret Whinney wrote that Chantrey "had a great gift for characterisation, his ability to render the softness of flesh was much admired" and that "though compelled by the fashion of the day to produce, on occasions, classicizing works, his robust common sense and his enormous talent is better displayed in works which combine an almost classical simplicity of form with naturalism in presentation".

Works

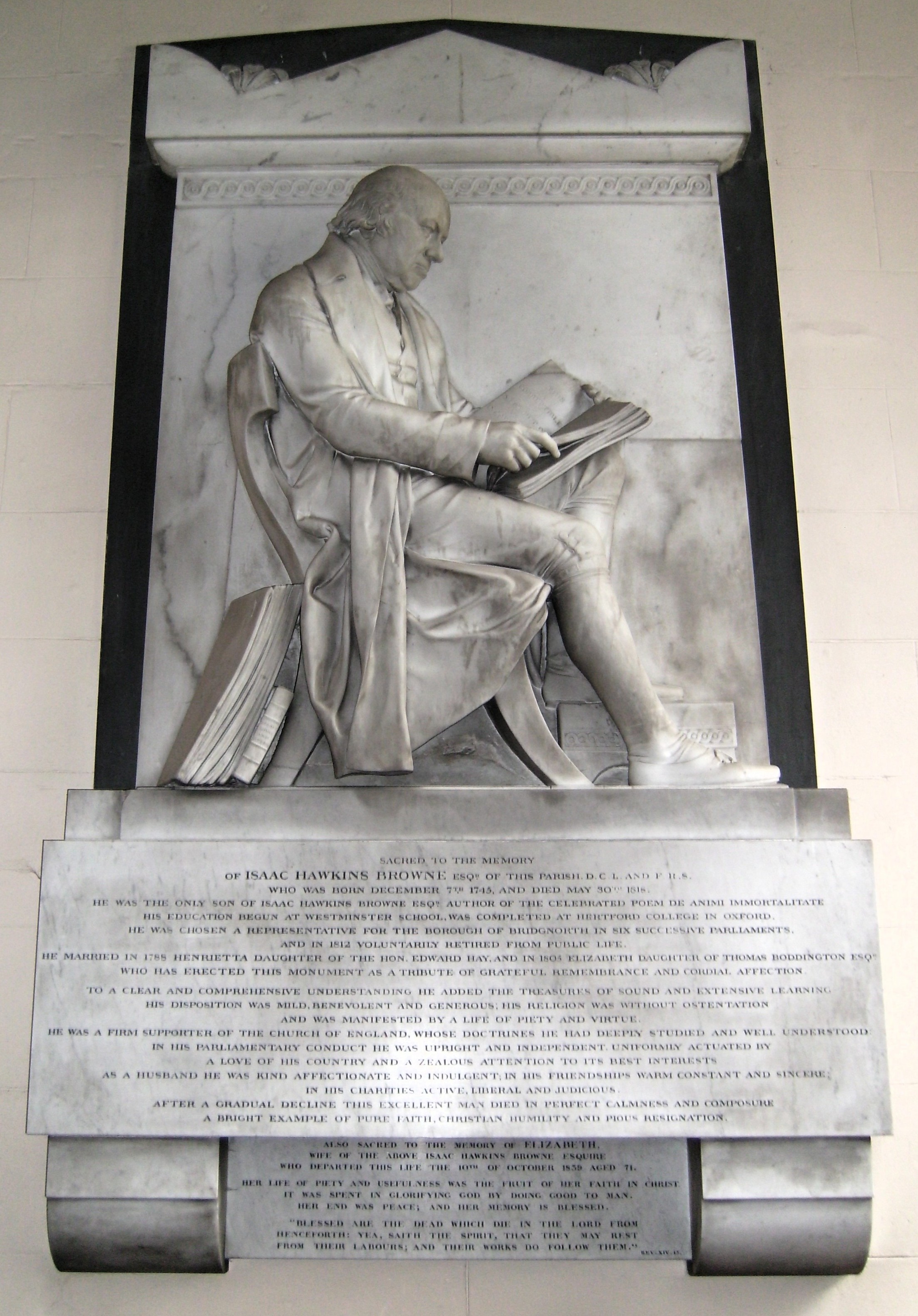

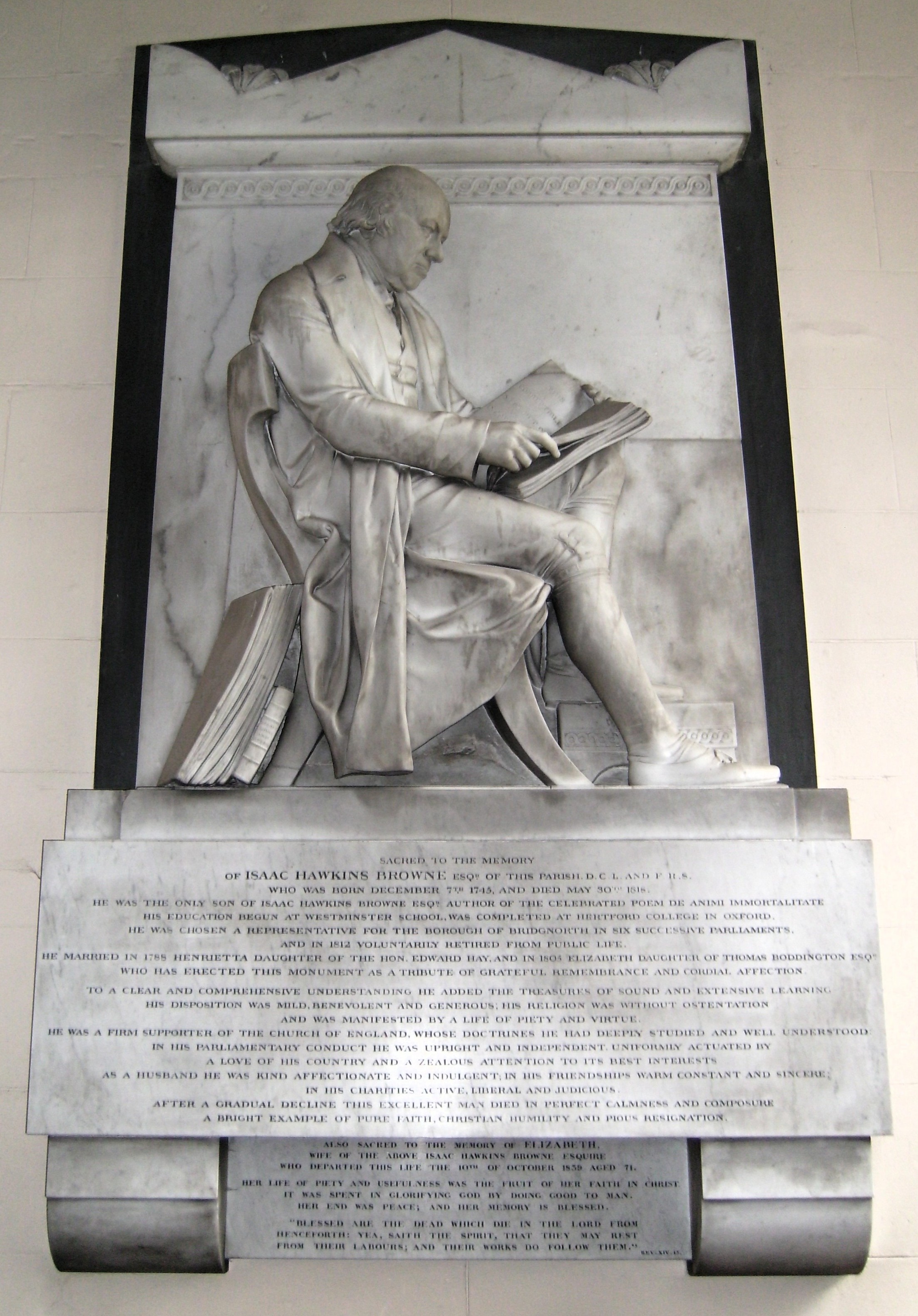

Chantrey was a prolific sculptor. According to an article published in 1842, he produced, besides his busts and reliefs, three equestrian statues, 18 standing ones, 18 seated ones and 14 recumbent figures. His most notable works include the statues of

Chantrey was a prolific sculptor. According to an article published in 1842, he produced, besides his busts and reliefs, three equestrian statues, 18 standing ones, 18 seated ones and 14 recumbent figures. His most notable works include the statues of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

in The Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a guild hall or guild house, is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Europe, with many surviving today in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commo ...

, London; of George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

in the Massachusetts State House

The Massachusetts State House, also known as the Massachusetts Statehouse or the New State House, is the List of state capitols in the United States, state capitol and seat of government for the Massachusetts, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, lo ...

; of George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

at Brighton

Brighton ( ) is a seaside resort in the city status in the United Kingdom, city of Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, England, south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze Age Britain, Bronze Age, R ...

(in bronze); of William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman who served as the last prime minister of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1783 until the Acts of Union 1800, and then first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, p ...

in Hanover Square, London (in bronze); of James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was f ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

and in Greenock (also a bust, plus one of William Murdoch

William Murdoch (sometimes spelled Murdock) (21 August 1754 – 15 November 1839) was a Scottish chemist, inventor, and mechanical engineer.

Murdoch was employed by the firm of Boulton & Watt and worked for them in Cornwall, as a steam engin ...

, at St. Mary's Church, Handsworth

St Mary's Church, Handsworth, also known as Handsworth Old Church, is a Grade II* listed Anglican church in Handsworth, Birmingham, England. Its ten-acre (4 hectare) grounds are contiguous with Handsworth Park. It lies just off the Bir ...

); of William Roscoe

William Roscoe (8 March 175330 June 1831) was an English banker, lawyer, and briefly a Member of Parliament. He is best known as one of England's first abolitionists, and as the author of the poem for children '' The Butterfly's Ball, and th ...

and George Canning

George Canning (; 11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as foreign secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the U ...

in Liverpool; of John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He introduced the atomic theory into chemistry. He also researched Color blindness, colour blindness; as a result, the umbrella term ...

in Manchester Town Hall

Manchester Town Hall is a Victorian era, Victorian, Gothic Revival architecture, Neo-gothic City and town halls, municipal building in Manchester, England. It is the ceremonial headquarters of Manchester City Council and houses a number of local ...

; of Lord President Blair and Lord Melville in Edinburgh.

He made a bronze equestrian statue of Thomas Munro for Madras (now Chennai

Chennai, also known as Madras (List of renamed places in India#Tamil Nadu, its official name until 1996), is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Tamil Nadu by population, largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost states and ...

) and another of King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

, originally commissioned, on the instructions of the King himself, to stand on top of the Marble Arch

The Marble Arch is a 19th-century white marble-faced triumphal arch in London, England. The structure was designed by John Nash in 1827 as the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace; it stood near the site of what is today th ...

, in front of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

, but eventually placed in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster in Central London. It was established in the early-19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. Its name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar, the Royal Navy, ...

. The horses in these two works are identical. A third, of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (; 1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was a British Army officer and statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures in Britain during t ...

for a site in front of the Royal Exchange in London, was completed after Chantrey's death.

He executed four monuments to military heroes for

He executed four monuments to military heroes for St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

: they commemorate Major-General Daniel Hoghton, Major-General Barnard Foord Bowes, and Colonel Henry Cadogan, and (in a single monument) Major-Generals Arthur Gore and John Byne Skerrett. He was also responsible for the memorials to Sir James Brisbane

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Sir James Brisbane, Order of the Bath, CB (1774 – 19 December 1826) was a British Royal Navy officer of the French Revolutionary Wars, French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Although never engaged in any majo ...

in St James' Church, Sydney and to Reginald Heber in Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

, a replica of which was made for St Paul's Cathedral in London. Other good examples of his church monuments are those to John Maxwell, 2nd Earl of Farnham (1826) in Urney Parish Church, Cavan and Mary Anne Boulton (1834) in Great Tew In Snaith church there is a notable monument to John Dawnay, 5th Viscount Downe by Chantrey.

One of his most famous works was '' The Sleeping Children'', a monument to two girls of the Robinson family, depicting them asleep in one another's arms, the younger holding a bunch of snowdrops. It attracted a great deal of attention when shown at the Royal Academy in 1817, before its installation in Lichfield Cathedral. The design of the monument was widely rumoured to be by Thomas Stothard

Thomas Stothard (17 August 1755 – 27 April 1834) was a British painter, illustrator and engraver.

His son, Robert T. Stothard was a painter (floruit, fl. 1810): he painted the proclamation outside York Minster of Queen Victoria's accession to ...

; Chantrey's biographer, James Holland, however gave more credence to another account of its history, according to which Stothard had merely made a drawing from Chantrey's preliminary model. Another popular work, much reproduced, was a small statue, made for Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

of the young Louisa, Lady Russell, depicted cradling a dove.

Derby Museum and Art Gallery has an unusual bust of William Strutt.

Honours

Chantrey was elected an Associate of theRoyal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

in 1816 and a full Academician in 1818. In 1822 Henry Wolsey Bayfield named Chantry Island in Ontario after him. He received the degree of MA from Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, and that of DCL from Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, and was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in 1835.

Death

He died suddenly at his home in Eccleston Street,Pimlico

Pimlico () is a district in Central London, in the City of Westminster, built as a southern extension to neighbouring Belgravia. It is known for its garden squares and distinctive Regency architecture. Pimlico is demarcated to the north by Lon ...

, London, on 25 November 1841, having suffered from heart disease for some years. He was buried in a tomb constructed by his assistant James Heffernan in the churchyard of his native village, Norton in Derbyshire (now a suburb of Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

).

Bequest

By his will, dated 31 December 1840, Chantrey (who had no children) left his whole residuary personal estate after the decease or on the second marriage of his widow (less certain specified annuities and bequests) in trust for the president and trustees of the Royal Academy (or in the event of its dissolution to such society as might take its place), the income to be devoted to the encouragement of British painting and sculpture, by "the purchase of works of fine art of the highest merit ... that can be obtained." The funds might be allowed to accumulate for not more than five years; works by British or foreign artists, dead or living, might be acquired, so long as such works were entirely executed within Great Britain, the artists having been in residence there during the execution and completion. The prices to be paid were to be "liberal," and no sympathy for an artist or his family was to influence the selection or the purchase of works, which were to be acquired solely on the ground of intrinsic merit. No commission or orders might be given: the works must be finished before purchase. Conditions were made as to the exhibition of the works, in the confident expectation that the government or the country would provide a suitable gallery for their display; and an annual sum of £300 and £50 was to be paid to the president and the secretary of the

By his will, dated 31 December 1840, Chantrey (who had no children) left his whole residuary personal estate after the decease or on the second marriage of his widow (less certain specified annuities and bequests) in trust for the president and trustees of the Royal Academy (or in the event of its dissolution to such society as might take its place), the income to be devoted to the encouragement of British painting and sculpture, by "the purchase of works of fine art of the highest merit ... that can be obtained." The funds might be allowed to accumulate for not more than five years; works by British or foreign artists, dead or living, might be acquired, so long as such works were entirely executed within Great Britain, the artists having been in residence there during the execution and completion. The prices to be paid were to be "liberal," and no sympathy for an artist or his family was to influence the selection or the purchase of works, which were to be acquired solely on the ground of intrinsic merit. No commission or orders might be given: the works must be finished before purchase. Conditions were made as to the exhibition of the works, in the confident expectation that the government or the country would provide a suitable gallery for their display; and an annual sum of £300 and £50 was to be paid to the president and the secretary of the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

respectively, for the discharge of their duties in carrying out the provisions of the will.

Lady Chantrey died in 1875 and was buried with

Lady Chantrey died in 1875 and was buried with George Jones

George Glenn Jones (September 12, 1931 – April 26, 2013) was an American Country music, country musician, singer, and songwriter. He achieved international fame for a long list of hit records, and is well known for his distinctive voice an ...

in Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in North London, England, designed by architect Stephen Geary. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East sides. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for so ...

, and two years later the fund became available for the purchase of paintings and sculptures. The capital sum available amounted to £105,000 in 3% Consols

Consols (originally short for consolidated annuities, but subsequently taken to mean consolidated stock) were government bond, government debt issues in the form of perpetual bonds, redeemable at the option of the government. The first British co ...

(reduced to 2½% in 1903), which was producing an available annual income varying between £2,100 and £2,500 by around 1910. Initially the works acquired were shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

, but in 1898 the Royal Academy arranged with the treasury, on behalf of the government, for the transfer of the collection to the National Gallery of British Art, which had been erected by Sir Henry Tate

Sir Henry Tate, 1st Baronet (11 March 18195 December 1899) was an English merchant and philanthropist, noted for establishing the Tate Britain, Tate Gallery and the company that became Tate & Lyle.

Early life

Henry Tate was born in White Copp ...

at Millbank

Millbank is an area of central London in the City of Westminster. Millbank is located by the River Thames, east of Pimlico and south of Westminster. Millbank is known as the location of major government offices, Burberry headquarters, the Mill ...

. It was agreed that the Tate Gallery

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the UK ...

should be its future home, but that the trustees and director of the National Gallery should have no power over what works were to be transferred there, or added to the collection at a later date.

By the end of 1905, 203 works had been bought—all but two from living artists—at a cost of nearly £68,000. Of these, 175 were oil paintings, 12 were watercolours, and 16 were sculptures. The bequest remained the main source of funding for expanding the collection of what is now Tate Britain until the 1920s, and it remains active today.

References

Sources

* * * * Attribution: *Further reading

*. A complete illustrated record of the purchases, etc.. * A controversial publication by the leading assailant of the Royal Academy. *''Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Chantrey Trust'', together with the ''Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence and Appendix'' (Wyman & Sons, 1904), and ''Index'' (separate publication, 1904).External links

* * *Works by Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey

at the

National Portrait Gallery National Portrait Gallery may refer to:

* National Portrait Gallery (Australia), in Canberra

* National Portrait Gallery (Sweden), in Mariefred

*National Portrait Gallery (United States), in Washington, D.C.

*National Portrait Gallery, London

...

, London

Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections

* , an image drawn by Henry Corbould and accompanied by

Felicia Hemans

Felicia Dorothea Hemans (25 September 1793 – 16 May 1835) was an English poet (who identified as Welsh by adoption). Regarded as the leading female poet of her day, Hemans was immensely popular during her lifetime in both England and the Unit ...

's poem, ''The Child's Last Sleep'', from the Friendship's Offering annual for 1826.

* , drawn by Henry Corbould from the statue at Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

and accompanied by Felicia Hemans

Felicia Dorothea Hemans (25 September 1793 – 16 May 1835) was an English poet (who identified as Welsh by adoption). Regarded as the leading female poet of her day, Hemans was immensely popular during her lifetime in both England and the Unit ...

's poem, ''The Child and Dove'', from The Literary Souvenir annual for 1826.

* , a poem by Felicia Hemans

Felicia Dorothea Hemans (25 September 1793 – 16 May 1835) was an English poet (who identified as Welsh by adoption). Regarded as the leading female poet of her day, Hemans was immensely popular during her lifetime in both England and the Unit ...

for the Forget Me Not annual for 1829 on ''The Sleeping Children'' in Lichfield Cathedral.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chantrey, Francis Leggatt

1781 births

1841 deaths

Burials at Highgate Cemetery

History of Sheffield

Artists from Sheffield

English sculptors

English male sculptors

Royal Academicians

Knights Bachelor

Fellows of the Royal Society

People from Derbyshire (before 1933)

19th-century English sculptors

19th-century English painters

English male painters

19th-century English male artists