Francis Amasa Walker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

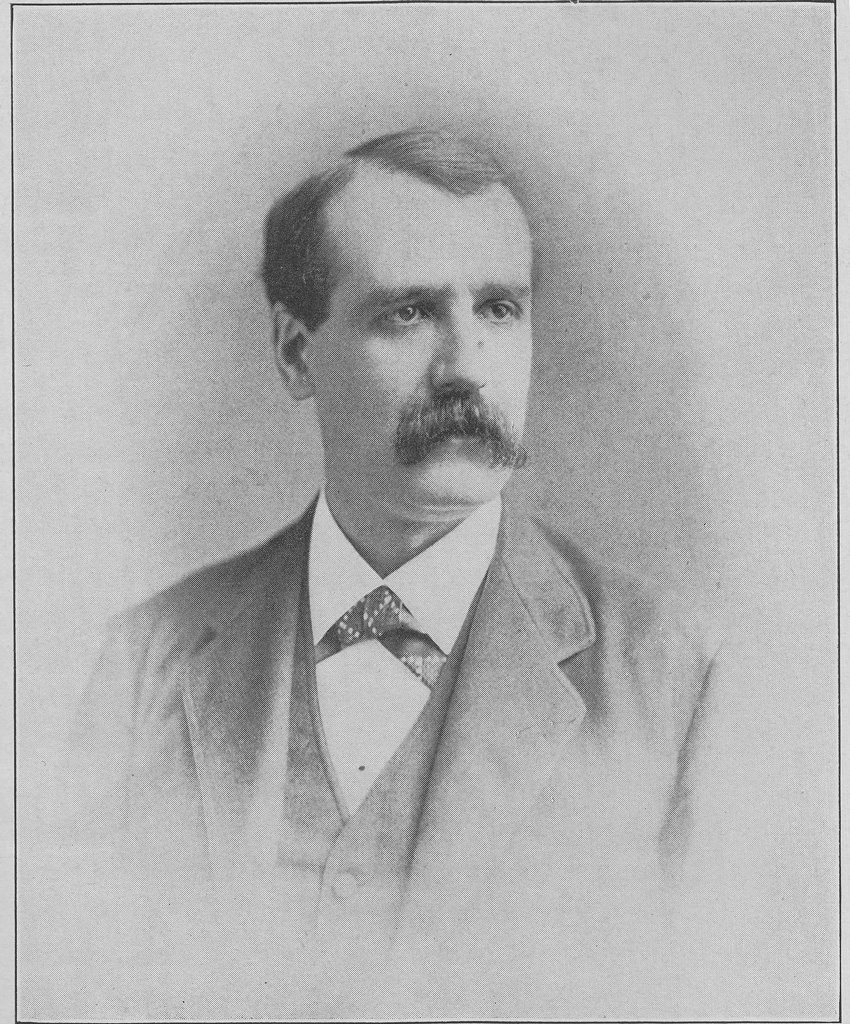

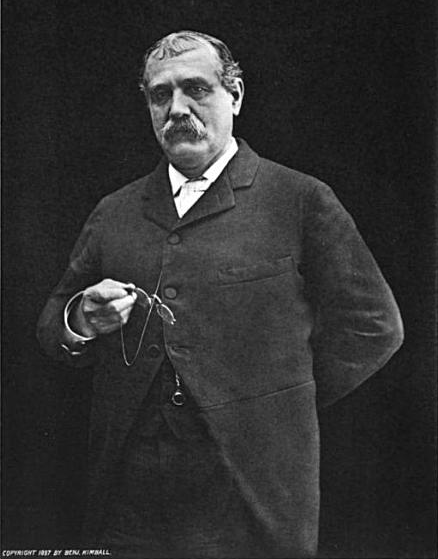

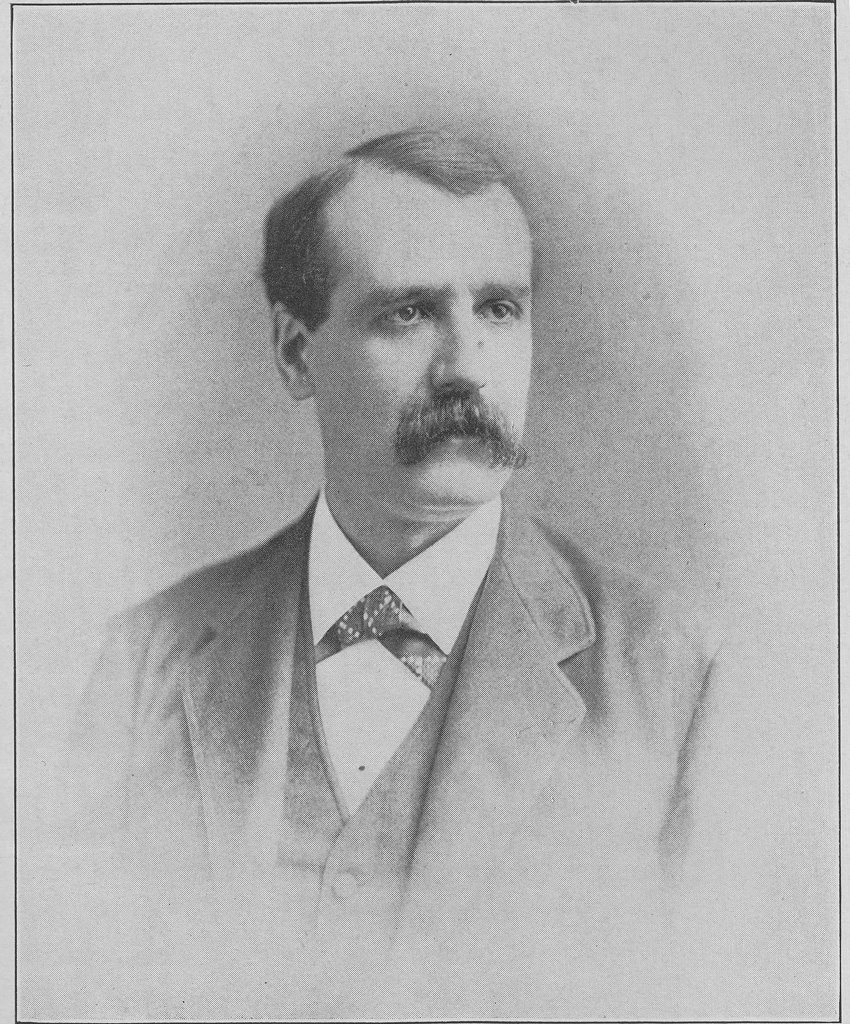

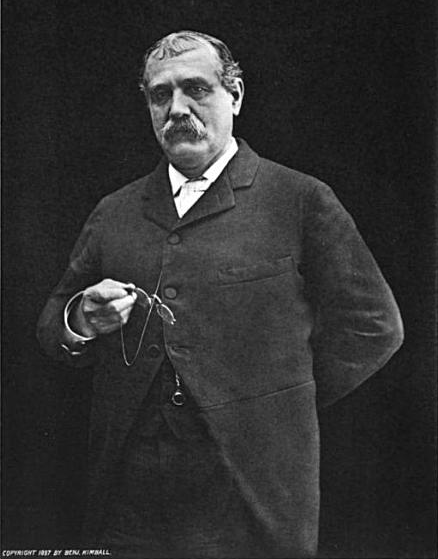

Francis Amasa Walker (July 2, 1840 – January 5, 1897) was an American

economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

, statistician

A statistician is a person who works with theoretical or applied statistics. The profession exists in both the private and public sectors.

It is common to combine statistical knowledge with expertise in other subjects, and statisticians may w ...

, journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalis ...

, educator

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. whe ...

, academic administrator

Academic administration is a branch of university or college employees responsible for the maintenance and supervision of the institution and separate from the faculty or academics, although some personnel may have joint responsibilities. Some ...

, and an officer in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

.

Walker was born into a prominent Boston family, the son of the economist and politician Amasa Walker

Amasa Walker (May 4, 1799 – October 29, 1875) was an American economist and United States Representative. He was the father of Francis Amasa Walker.

Biography

He moved with his parents to North Brookfield, Massachusetts, and attended the dis ...

, and he graduated from Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educati ...

at the age of 20. He received a commission to join the 15th Massachusetts Infantry and quickly rose through the ranks as an assistant adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

. Walker fought in the Peninsula Campaign and was wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

but subsequently participated in the Bristoe, Overland, and Richmond-Petersburg Campaigns before being captured by Confederate forces and held at the infamous Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army. It gained an infamous reputation for the overcrowded and harsh conditions. Priso ...

. In July 1866, he was nominated by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

and confirmed by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

for the award of the honorary grade of brevet brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

United States Volunteers

United States Volunteers also known as U.S. Volunteers, U.S. Volunteer Army, or other variations of these, were military volunteers called upon during wartime to assist the United States Army but who were separate from both the Regular Army and t ...

, to rank from March 13, 1865, when he was 24 years old.

Following the war, Walker served on the editorial staff of the ''Springfield Republican

''The Republican'' is a newspaper based in Springfield, Massachusetts covering news in the Greater Springfield area, as well as national news and pieces from Boston, Worcester and northern Connecticut. It is owned by Newhouse Newspapers, a ...

'' before using his family and military connections to gain appointment as the chief of the Bureau of Statistics

The following is a list of national and international statistical services.

Central national statistical services

Nearly every country in the world has set a central public sector unit entirely devoted to the production, harmonisation and dissemin ...

from 1869 to 1870 and superintendent of the 1870 census

The United States census of 1870 was the ninth United States census. It was conducted by the Census Bureau from June 1, 1870, to August 23, 1871. The 1870 census was the first census to provide detailed information on the African-American popu ...

where he published an award-winning ''Statistical Atlas'' visualizing the data for the first time. He joined Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

's Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffiel ...

as a professor of political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour ...

in 1872 and rose to international prominence serving as a chief member of the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, American representative to the 1878 International Monetary Conference The international monetary conferences were a series of assemblies held in the second half of the 19th century. They were held with a view to reaching agreement on matters relating to international relationships between national currency systems.

B ...

, President of the American Statistical Association

The American Statistical Association (ASA) is the main professional organization for statisticians and related professionals in the United States. It was founded in Boston, Massachusetts on November 27, 1839, and is the second oldest continuousl ...

in 1882, and inaugural president of the American Economic Association

The American Economic Association (AEA) is a learned society in the field of economics. It publishes several peer-reviewed journals acknowledged in business and academia. There are some 23,000 members.

History and Constitution

The AEA was esta ...

in 1886, and vice president of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

in 1890. Walker also led the 1880 census

The United States census of 1880 conducted by the Census Bureau during June 1880 was the tenth United States census.wage-fund doctrine and engaged in a prominent scholarly debate with

Beginning his schooling at the age of seven, Walker studied Latin at various private and public schools in Brookfield before being sent to the Leicester Academy when he was twelve. He completed his college preparation by the time he was fourteen and spent another year studying Greek and Latin under the future

Beginning his schooling at the age of seven, Walker studied Latin at various private and public schools in Brookfield before being sent to the Leicester Academy when he was twelve. He completed his college preparation by the time he was fourteen and spent another year studying Greek and Latin under the future

Walker remained at the Berkeley Plantation until his promotion on August 11 to

Walker remained at the Berkeley Plantation until his promotion on August 11 to

As his Census obligations diminished in 1872, Walker reconsidered becoming an editorialist and even briefly entertained the idea of becoming a shoe manufacturer with his brother-in-law back in North Brookfield. However, in October 1872, he was unanimously offered to fill

As his Census obligations diminished in 1872, Walker reconsidered becoming an editorialist and even briefly entertained the idea of becoming a shoe manufacturer with his brother-in-law back in North Brookfield. However, in October 1872, he was unanimously offered to fill

Established in 1861 and opened in 1865, the

Established in 1861 and opened in 1865, the  MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the Lawrence Scientific School at

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the Lawrence Scientific School at

Walker sought to erect a new building to address the increasingly cramped conditions of the original

Walker sought to erect a new building to address the increasingly cramped conditions of the original

Although Walker continued Census-related activities, he began to lecture on political economy as well as establishing a new general course of study (Course IX) emphasizing economics, history, law, English, and modern languages. Walker also set out to reform and expand the Institute's organization by creating a smaller Executive Committee, apart from the fifty-member Corporation, to handle regular administrative issues. Walker emphasized the importance of faculty governance by regularly attending their meetings and seeking their advice on major decisions.

Walker also sought to improve the state of student life and alumni relations by supporting the creation of a gymnasium, dormitories, and the Technology Club, which served to foster a stronger identity and loyalty among the largely commuter student body. He also won considerable praise from the student body by reducing the required time spent for recitation and preparation, limiting the faculty to examinations lasting no longer than three hours, expanding entrance examinations to other cities, starting a summer curriculum, and launching masters and doctoral graduate degree programs. These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, inapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school. Between 1881 and 1897, enrollments quadrupled from 302 to 1,198 students, annual degrees granted increased from 28 to 179, faculty appointments quadrupled from 38 to 156, and the endowment grew thirteenfold from $137,000 to $1,798,000 ($ to $ in 2016 dollars).

While MIT is a private institution, Walker's extensive civic activities as President set the precedent for future presidents to use the post to fulfill civic and cultural obligations throughout Boston. He served as a member of the

Although Walker continued Census-related activities, he began to lecture on political economy as well as establishing a new general course of study (Course IX) emphasizing economics, history, law, English, and modern languages. Walker also set out to reform and expand the Institute's organization by creating a smaller Executive Committee, apart from the fifty-member Corporation, to handle regular administrative issues. Walker emphasized the importance of faculty governance by regularly attending their meetings and seeking their advice on major decisions.

Walker also sought to improve the state of student life and alumni relations by supporting the creation of a gymnasium, dormitories, and the Technology Club, which served to foster a stronger identity and loyalty among the largely commuter student body. He also won considerable praise from the student body by reducing the required time spent for recitation and preparation, limiting the faculty to examinations lasting no longer than three hours, expanding entrance examinations to other cities, starting a summer curriculum, and launching masters and doctoral graduate degree programs. These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, inapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school. Between 1881 and 1897, enrollments quadrupled from 302 to 1,198 students, annual degrees granted increased from 28 to 179, faculty appointments quadrupled from 38 to 156, and the endowment grew thirteenfold from $137,000 to $1,798,000 ($ to $ in 2016 dollars).

While MIT is a private institution, Walker's extensive civic activities as President set the precedent for future presidents to use the post to fulfill civic and cultural obligations throughout Boston. He served as a member of the

Walker married Exene Evelyn Stoughton on August 16, 1865 (born October 11, 1840). They had five sons and two daughters together: Stoughton (b. June 3, 1866), Lucy (b. September 1, 1867), Francis (b. 1870–1871), Ambrose (b. December 28, 1870), Eveline (b. 1875–1876), Etheredge (b. 1876–1877), and Stuart (b. 1878–1879). Walker was an avid spectator and supporter of college football and baseball, and was a regular Yale enthusiast at the annual Harvard-Yale football game, even during his MIT presidency.

Following a trip to a dedication in the "wilderness of Northern New York" in December 1896, Walker returned exhausted and ill. He died on January 5, 1897, as a result of

Walker married Exene Evelyn Stoughton on August 16, 1865 (born October 11, 1840). They had five sons and two daughters together: Stoughton (b. June 3, 1866), Lucy (b. September 1, 1867), Francis (b. 1870–1871), Ambrose (b. December 28, 1870), Eveline (b. 1875–1876), Etheredge (b. 1876–1877), and Stuart (b. 1878–1879). Walker was an avid spectator and supporter of college football and baseball, and was a regular Yale enthusiast at the annual Harvard-Yale football game, even during his MIT presidency.

Following a trip to a dedication in the "wilderness of Northern New York" in December 1896, Walker returned exhausted and ill. He died on January 5, 1897, as a result of

Following Walker's death, alumni and students began to raise funds to construct a monument to him and his fifteen years as leader of the university. Although the funds were easily raised, plans were delayed for over two decades as MIT made plans to move to a new campus on the western bank of the

Following Walker's death, alumni and students began to raise funds to construct a monument to him and his fifteen years as leader of the university. Although the funds were easily raised, plans were delayed for over two decades as MIT made plans to move to a new campus on the western bank of the

The Indian Question

' (1874) *

The Wages Question: A treatise on Wages and the Wages Class

' (1876)

''Money''

(1878) *

Money in its Relation to Trade and Industry

' (1879)

''Political Economy''

(first edition, 1883) *

Land and its Rent

' (1883) *

History of the Second Army Corps

' (1886) *

Life of General Hancock

' (1894) *

The Making of the Nation

' (1895) *

International Bimetallism"> International Bimetallism

' (1896)

Biographical note – MIT Archives

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Walker, Francis Amasa 1840 births 1897 deaths American biographers American economics writers 19th-century American economists American Civil War prisoners of war Amherst College alumni Boston School Committee members People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Writers from Boston Presidents of the American Statistical Association Presidents of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Union Army generals American statisticians Sheffield Scientific School faculty American columnists United States Census Bureau people Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Connecticut Republicans Massachusetts Republicans People from North Brookfield, Massachusetts 19th-century American journalists American male journalists 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American politicians Members of the American Antiquarian Society Presidents of the American Economic Association Mathematicians from Connecticut Economists from Massachusetts Trustees of the Boston Public Library American male biographers The Boston Post people

Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

on land, rent, and taxes. Walker argued in support of bimetallism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betw ...

and although he was an opponent of the nascent socialist movement

The history of socialism has its origins in the 1789 French Revolution and the changes which it brought, although it has precedents in earlier movements and ideas. ''The Communist Manifesto'' was written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1847-4 ...

, he argued that obligations existed between the employer and the employed. He published his ''International Bimetallism'' at the height of the 1896 presidential election campaign in which economic issues were prominent. Walker was a prolific writer, authoring ten books on political economy and military history. In recognition of his contributions to economic theory, beginning in 1947, the American Economic Association recognized the lifetime achievement of an individual economist with a "Francis A. Walker Medal".

Walker accepted the presidency of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

in 1881, a position he held for fifteen years until his death. During his tenure, he placed the institution on more stable financial footing by aggressively fund-raising and securing grants from the Massachusetts government, implemented many curricular reforms, oversaw the launch of new academic programs, and expanded the size of the Boston campus, faculty, and student enrollments. MIT's Walker Memorial Hall, a former students' clubhouse and one of the original buildings on the Charles River campus, was dedicated to him in 1916.

Background

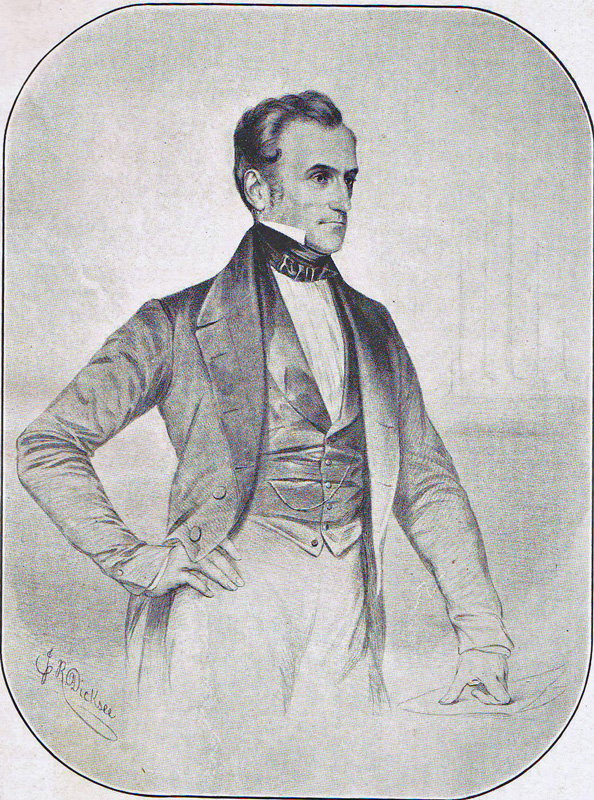

Walker was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the youngest son of Hanna (née Ambrose) andAmasa Walker

Amasa Walker (May 4, 1799 – October 29, 1875) was an American economist and United States Representative. He was the father of Francis Amasa Walker.

Biography

He moved with his parents to North Brookfield, Massachusetts, and attended the dis ...

, a prominent economist and state politician. The Walkers had three children, Emma (born 1835), Robert (born 1837), and Francis. Because the Walkers' next-door neighbor was Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., the junior Walker and junior Holmes were playmates as young children and renewed their friendship later in life. The family moved from Boston to North Brookfield, Massachusetts

North Brookfield is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 4,735 at the 2020 census.

For geographic and demographic information on the census-designated place North Brookfield, please see the article North ...

, in 1843 and remained there. As a boy he had both a noted temper as well as a magnetic personality.

Beginning his schooling at the age of seven, Walker studied Latin at various private and public schools in Brookfield before being sent to the Leicester Academy when he was twelve. He completed his college preparation by the time he was fourteen and spent another year studying Greek and Latin under the future

Beginning his schooling at the age of seven, Walker studied Latin at various private and public schools in Brookfield before being sent to the Leicester Academy when he was twelve. He completed his college preparation by the time he was fourteen and spent another year studying Greek and Latin under the future suffragist

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

, and entered Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educati ...

at the age of fifteen. Although he had planned to matriculate at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

after his first year at Amherst, Walker's father believed his son was too young to enter the larger college and insisted he remain at Amherst. While he had entered with the class of 1859, Walker became ill during his first year there and fell back a year. He was a member of the Delta Kappa and Athenian societies as a freshman, joined and withdrew from Alpha Sigma Phi

Alpha Sigma Phi (), commonly known as Alpha Sig, is an intercollegiate men's social fraternity with 181 active chapters and provisional chapters. Founded at Yale in 1845, it is the 10th oldest Greek letter fraternity in the United States.

The ...

as a sophomore on account of "rowdyism", and finally joined Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon (), commonly known as ''DKE'' or ''Deke'', is one of the oldest fraternities in the United States, with fifty-six active chapters and five active colonies across North America. It was founded at Yale College in 1844 by fiftee ...

. As a student, Walker was awarded the Sweetser Essay Prize and the Hardy Prize for extemporaneous speaking. He graduated in 1860 as Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

with a degree in law. After graduation, he joined the law firm of Charles Devens

Charles Devens Jr. (April 4, 1820 – January 7, 1891) was an American lawyer, jurist and statesman. He also served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Early life and career

Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, Devens gr ...

and George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 to 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politically prominen ...

in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 census, making it the second- most populous city in New England after ...

.

Military service

15th Massachusetts Infantry

As tensions between the North and South increased over the winter of 1860–1861, Walker equipped himself and began drilling with Major Devens' 3rd Battalion of Rifles in Worcester and New York. Despite his older brother Robert serving in the 34th Massachusetts Infantry, his father objected to his youngest son mobilizing with the first wave of volunteers. Walker returned to Worcester but began to lobbyWilliam Schouler

William Schouler (December 31, 1814 – October 24, 1872) was an American journalist, politician and Adjutant General of Massachusetts during the American Civil War.

Early life

Schouler was born on December 31, 1814, in Kilbarchan, Renfrewshi ...

and Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

John Andrew to grant him a commission as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

under Devens' command of the 15th Massachusetts. Following his 21st birthday and the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

in July 1861, Walker secured the consent of his father to join the war effort as well as assurances by Devens that he would receive an officer's commission. However, the lieutenancy never materialized and Devens instead offered Walker an appointment as a sergeant major

Sergeant major is a senior non-commissioned rank or appointment in many militaries around the world.

History

In 16th century Spain, the ("sergeant major") was a general officer. He commanded an army's infantry, and ranked about third in th ...

, which he assumed on August 1, 1861, after re-tailoring his previously ordered lieutenant's uniform to reflect his enlisted status. However, by September 14, 1861, Walker had been recommended by Devens and reassigned to Brig. Gen. Darius N. Couch

Darius Nash Couch (July 23, 1822 – February 12, 1897) was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career U.S. Army officer during the Mexican–American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general officer in the Uni ...

as assistant adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

and promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. Walker remained in Washington, D.C., over the winter of 1861–1862 and did not see combat until May 1862 at the Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first p ...

. Walker also served at Seven Pines as well as at the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

of the Peninsula Campaign in the summer of 1862 under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

.

Second Army Corps

Walker remained at the Berkeley Plantation until his promotion on August 11 to

Walker remained at the Berkeley Plantation until his promotion on August 11 to major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

and transferral with General Couch to the II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

of the Army of the Potomac. Although the II Corps later saw action at the battles of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

and Fredericksburg, the latter being under the new command of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

, Walker and the Corps did not join Burnsides's Mud March over the winter. Walker was promoted to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

on January 1, 1863, and remained with the II Corps. He fought the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

in May 1863, where his hand and wrist were shattered and neck lacerated by an exploding shell. A record of the 1880 Census indicated that he had "compound fracture of the metacarpal bones of the left hand resulting in permanent extension of his hand". Later in 1896, as the president of MIT, he would receive one of the first radiograph

Radiography is an imaging technique using X-rays, gamma rays, or similar ionizing radiation and non-ionizing radiation to view the internal form of an object. Applications of radiography include medical radiography ("diagnostic" and "therapeut ...

s in the country, which documented the extent of the damage to his hand. He did not return to service until August 1863. Walker participated in the Bristoe Campaign and narrowly escaped encirclement during the Battle of Bristoe Station before withdrawing and encamping near the Berry Hill Plantation for much of the winter and spending some leave in the North.

After extensive reorganization during the winter of 1863–1864, Walker and the Army of the Potomac fought in the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

through May and June 1864. The Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses ...

in early June took a substantial toll on the ranks of the II Corps and Walker injured his knee during the battle. In the ensuing Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, Walker was appointed a brevet colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

. However, on August 25, 1864, as he rode to find Maj. Gen. John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the four ...

at the front during the Second Battle of Ream's Station, Walker was surrounded and captured by the 11th Georgia Infantry. On August 27, Walker was able to escape from a marching prisoner column with another prisoner but was recaptured by the 51st North Carolina Infantry after trying to swim across the Appomattox River

The Appomattox River is a tributary of the James River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 in central and eastern Virginia in the United S ...

and nearly drowning. After being held as a prisoner in Petersburg, he was transferred to the infamous Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army. It gained an infamous reputation for the overcrowded and harsh conditions. Priso ...

in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

, where his older brother was also held. In October 1864, Walker was released with thirty other prisoners as a part of an exchange.

Walker returned to North Brookfield to recuperate and resigned his commission on January 8, 1865, as a result of his injuries and health. At the end of the war, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

recommended that Walker be brevetted as a brigadier general of U.S. Volunteers in recognition of his meritorious services during the war and especially his gallant conduct at Chancellorsville. On July 9, 1866, Walker was nominated by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

for appointment to the honorary grade of brevet brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

, U.S. Volunteers

United States Volunteers also known as U.S. Volunteers, U.S. Volunteer Army, or other variations of these, were military volunteers called upon during wartime to assist the United States Army but who were separate from both the Regular Army and the ...

, to rank from March 13, 1865 (when he was age 24), for gallant conduct at the battle of Chancellorsville and meritorious services during the war. The U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on July 23, 1866.

After the war, Walker became a companion of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or simply the Loyal Legion is a United States patriotic order, organized April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Army. The original membership was composed of members ...

. Based upon his experiences in the military, Walker published two books describing the history of II Corps (1886) as well as a biography of General Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

(1884). Walker was elected Commander of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or simply the Loyal Legion is a United States patriotic order, organized April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Army. The original membership was composed of members ...

in 1883 was also the president of the National Military Historical Association.

Postbellum activity

By late spring 1865, Walker regained sufficient strength and began to assist his father by lecturing on political economy at Amherst as well as assisting him in the preparation of ''The Science of Wealth.'' He also taught Latin, Greek, and mathematics at the Williston Seminary in Easthampton, Massachusetts until being offered an editorial position at the ''Springfield Republican

''The Republican'' is a newspaper based in Springfield, Massachusetts covering news in the Greater Springfield area, as well as national news and pieces from Boston, Worcester and northern Connecticut. It is owned by Newhouse Newspapers, a ...

'' by Samuel Bowles. At the ''Republican,'' Walker wrote on Reconstruction era politics, railroad regulation, and representation.

1870 Census

While his editorial career was moving forward, Walker called upon his own as well as his father's political contacts to secure an appointment underDavid Ames Wells

David Ames Wells (June 17, 1828 – November 5, 1898) was an American engineer, textbook author, economist and advocate of low tariffs.

Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, he graduated from Williams College in 1847. In 1848 he joined the staff ...

as the chief of the U.S. Bureau of Statistics and deputy special commissioner of Internal Revenue in January 1869. On January 29, 1869, Major General J.D. Cox, who had also previously served in McClellan's army and was currently the Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Grant's administration, notified the twenty-nine-year-old Walker that he was being nominated to become the superintendent of the 1870 census

The United States census of 1870 was the ninth United States census. It was conducted by the Census Bureau from June 1, 1870, to August 23, 1871. The 1870 census was the first census to provide detailed information on the African-American popu ...

. After he was confirmed by the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, Walker sought to strike a moderate reformist position free from the inefficient and unscientific methods of the 1850 and 1860 censuses; however, the required legislation was not passed and the census proceeded under the rules governing previous collections. Among the problems facing Walker included a lack of authority to determine, enforce, or control the marshals personnel, methods, or timing all of which were regularly manipulated by local political interests. Additionally, the 1870 Census would not only occur five years after Civil War but would also be the first in which emancipated

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchi ...

African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s would be fully counted in the census.

Owing to the confluence of these problems, the Census was completed and tabulated several months behind schedule to much popular criticism, and led indirectly to a deterioration in Walker's health during the spring of 1871. Walker took leave to travel to England with Bowles that summer to recuperate and upon return that fall, despite an offer from ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' to join their editorial board with an annual salary of $8,000 ($ in 2016), accepted Secretary Columbus Delano's offer to become the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs in November 1871. The appointment was simultaneously a go-around to continue to fund Walker's federal responsibilities as Census superintendent despite Congress' cessation of appropriations for the position as well as a political opportunity to replace a scandal-ridden predecessor. Walker continued to work on the Census for several years thereafter, culminating in the publication of the ''Statistical Atlas of the United States'' that was unprecedented in its use of visual statistics and maps to report the results of the Census. The ''Atlas'' won him praise from both the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

as well as a First Class medal from the International Geographical Congress.

Indian Bureau

Despite his Census-related efforts, Walker did not neglect his obligations as Indian affairs superintendent. However, Walker’s frustration with the treatment of Native Americans caused his resignation after only one year on December 26, 1872 to take a faculty position at Yale. During his brief assignment, he collected demographic information on native tribes and on the history of conflict and treaties, which he published in 1874 as a book titled ''The Indian Question''. More than half of the book is dedicated to an appendix with descriptions of over 100 tribes which he describes as including 300,000 natives, the majority of which were living on existing government reservations. The remainder of the work proposes policy options for future government actions. A central theme of Walker’s book is to consider two options for future relationships to the Native Americans: seclusion on reservations or citizenship. He warns that the current reservation system is failing due to unabated illegal incursion into the native lands. He provides examples of how the alternative of immediate full assimilation as citizens is damaging native culture, quality of life, and dignity. Walker’s conclusions are that assimilation as citizens must be the ultimate end goal, but to accomplish this in an orderly manner over time requires protection of the indigenous population “under the shell of the reservation system.” He proposes detailed recommendations including consolidation of the existing 92 reservations into fewer larger units; laws and enforcement to stop settler incursions; government sponsored training programs within the reservations; and ongoing federal financial support based on an endowment and not annual appropriations. Walker makes a number of moral arguments to support reparations for past actions toward Native Americans, including : “We may have no fear that the dying curse of the red man, outcast and homeless by our fault, will bring barrenness upon the soil that once was his, or dry the streams of the beautiful land that, through so much of evil and of good, has become our patrimony ; but surely we shall be clearer in our lives, and freer to meet the glances of our sons and grandsons, if in our generation we do justice and show mercy to a race which has been impoverished that we might be made rich.” He elevated the treatment of the natives to be one of the great issues of the time: “The United States will be judged at the bar of history according to what they shall have done in two respects, -by their disposition of negro slavery, and by their treatment of the Indians.”Other engagements

1876 was a busy year for Walker.Henry Brooks Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fran ...

sought to recruit Walker to be the editor-in-chief of his '' Boston Post'' after failing to recruit Horace White and Charles Nordhoff

Charles Bernard Nordhoff (February 1, 1887 – April 10, 1947) was an American novelist and traveler, born in England. Nordhoff is perhaps best known for '' The Bounty Trilogy'', three historical novels he wrote with James Norman Hall: ''Mutiny ...

for the position. That spring, Walker was nominated to run for the Secretary of the State of Connecticut

The secretary of the State of Connecticut is one of the constitutional officers of the U.S. state of Connecticut. (The definite article is part of the legal job title.) It is an elected position in the state government and has a term length of four ...

, running on a platform that would later be embodied by the "Mugwump

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. Typically they switched parties from the Republican Party by supporting Democratic ...

" movement, but ultimately lost to Marvin H. Sanger by a margin of 7,200 votes out of 99,000 cast. In the summer, the faculty of Amherst attempted to recruit him to become the President, but the position went instead to the Rev. Julius Hawley Seelye to appease the more conservative trustees.

Walker's rise to prominence was further accelerated by his appointment by Charles Francis Adams, Jr. as the chief of the Bureau of Awards at the 1876 Centennial Exposition

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official World's Fair to be held in the United States, was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May 10 to November 10, 1876, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the ...

in Philadelphia. Previous world expositions in Europe were fraught with national factionalism and a superabundance of awards. Walker imposed a much leaner operation replacing juries with judges and being more selective in awarding prizes. Walker won formal international recognition when he was named a "Knight Commander" by Sweden and Norway and a "Comendador" by Spain. He was also invited to serve as Assistant Commissioner General for the 1878 Paris Exposition. The Centennial Exposition affected Walker's later career by greatly increasing his interest in technical education as well as introducing him to MIT President John D. Runkle

John Daniel Runkle (October 11, 1822 – July 8, 1902) was a U.S. educator and mathematician. He served as acting president of MIT from 1868–70 and president between 1870 and 1878.

Biography

Professor Runkle was born at Root, New York State. H ...

and Treasurer John C. Cummings.

1880 Census

Walker accepted a re-appointment as the superintendent of the1880 Census

The United States census of 1880 conducted by the Census Bureau during June 1880 was the tenth United States census.Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

James A. Garfield, had been passed to allow him to appoint trained census enumerators free from political influence. Notably, the 1880 Census's results suggested population throughout the Southern states had increased improbably over Walker's 1870 census but an investigation revealed that the latter had been inaccurately enumerated. Walker publicized the discrepancy even as it effectively discredited the accuracy his 1870 work. The tenth Census resulted in the publication of twenty-two volumes, was popularly regarded as the best census of any up to that time, and definitively established Walker's reputation as the preeminent statistician in the nation. The Census was again delayed as a result of its size and was the subject of praise and criticism on its comprehensiveness and relevance. Walker also used the position as a bully pulpit

A bully pulpit is a conspicuous position that provides an opportunity to speak out and be listened to.

This term was coined by United States President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), ...

to advocate for the creation of a permanent Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the Federal Statistical System of the United States, U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the Americans, Ame ...

to not only ensure that professional statisticians could be trained and retained but that the information could be better popularized and disseminated. Following Garfield's 1880 election, there was wide speculation that he would name Walker to be Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

, but Walker had accepted the offer to become President of MIT in the spring of 1881 instead.

Social Darwinism

Walker was a strong believer insocial Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

. In 1896, he wrote an article in the ''Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'' titled "Restriction of Immigration," in which he said immigrants from Austria, Italy, Hungary, and Russia were nothing more than "vast masses of peasantry, degraded below our utmost conceptions . . . beaten men from beaten races, representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence."

According to historian Mae Ngai

Mae Ngai is an American historian and Lung Family Professor of Asian American Studies and Professor of History at Columbia University. She focuses on nationalism, citizenship, ethnicity, immigration, and race in 20th-century United States his ...

, Walker believed the United States "possessed a natural character and teleology, to which immigration was external and unnatural. isassumption resonated with conventional views about America's providential mission and the general march of progress. Yet, it was rooted in a profoundly conservative viewpoint that the composition of the American nation should never change."

Walker's theories and writing were foundational for the American nativist movement.

Academic career

As his Census obligations diminished in 1872, Walker reconsidered becoming an editorialist and even briefly entertained the idea of becoming a shoe manufacturer with his brother-in-law back in North Brookfield. However, in October 1872, he was unanimously offered to fill

As his Census obligations diminished in 1872, Walker reconsidered becoming an editorialist and even briefly entertained the idea of becoming a shoe manufacturer with his brother-in-law back in North Brookfield. However, in October 1872, he was unanimously offered to fill Daniel Coit Gilman

Daniel Coit Gilman (; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic. Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College, and subsequently served as the second president of the University ...

's vacated post at Yale's recently established Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffiel ...

led by the mineralogist

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

George Jarvis Brush. While at Yale, Walker served as a member of the School Committee at New Haven (1877–1880) and the Connecticut Board of Education (1878–1881).

Walker was awarded honorary or ''ad eundem

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a product or service. Advertising aims to put a product or service in the spotlight in hopes of drawing it attention from consumers. It is typically used to promote a ...

'' degrees from Amherst (M.A. 1863, Ph.D. 1875, LL.D. 1882), Yale (M.A. 1873, LL.D. 1882), Harvard (LL.D. 1883), Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region i ...

(LL.D. 1887), St. Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's four ...

(LL.D. 1888), Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

(LL.D. 1892), Halle Halle may refer to:

Places Germany

* Halle (Saale), also called Halle an der Saale, a city in Saxony-Anhalt

** Halle (region), a former administrative region in Saxony-Anhalt

** Bezirk Halle, a former administrative division of East Germany

** Hal ...

(Ph.D. 1894), and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

(LL.D. 1896). He was elected as an honorary member of the Royal Statistical Society

The Royal Statistical Society (RSS) is an established statistical society. It has three main roles: a British learned society for statistics, a professional body for statisticians and a charity which promotes statistics for the public good.

...

in 1875, a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society i ...

in 1876, and a member of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

in 1878 where he served as the vice president from 1890 until his death. In addition to being elected as the president of the American Statistical Association

The American Statistical Association (ASA) is the main professional organization for statisticians and related professionals in the United States. It was founded in Boston, Massachusetts on November 27, 1839, and is the second oldest continuousl ...

in 1882, he helped found and launch the International Statistical Institute

The International Statistical Institute (ISI) is a professional association of statisticians. It was founded in 1885, although there had been international statistical congresses since 1853. The institute has about 4,000 elected members from gov ...

in 1885 and was named its "''President-adjoint''" in 1893. Walker also served as the inaugural president of the American Economic Association

The American Economic Association (AEA) is a learned society in the field of economics. It publishes several peer-reviewed journals acknowledged in business and academia. There are some 23,000 members.

History and Constitution

The AEA was esta ...

from 1885 to 1892. He took appointments as a lecturer at Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

(its first professor of economics) from 1877 to 1879, lecturer at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

in 1882, 1883, and 1896, and trustee at Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educati ...

from 1879 to 1889.

Wages-fund theory

Walker's scholarly contributions are widely recognized as having broadened, liberalized, and modernized economic and statistical theory with his contributions to wages, wealth distribution, money, and social economics. Although his arguments presage bothneoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good ...

and institutionalism, he is not readily classified into either. As a Professor of Political Economy, his first major scholarly contribution was on his ''The Wages Question'' which set out to debunk the wage-fund doctrine as well as address the then-radical notion of obligations between the employer and the employed. His theory of wage distribution later came to be known as residual theory and set the stage for contributions by John Bates Clark

John Bates Clark (January 26, 1847 – March 21, 1938) was an American neoclassical economist. He was one of the pioneers of the marginalist revolution and opponent to the Institutionalist school of economics, and spent most of his career as ...

on the marginal productivity theory. Despite Walker's advocacy of profit sharing

Profit sharing is various incentive plans introduced by businesses that provide direct or indirect payments to employees that depend on company's profitability in addition to employees' regular salary and bonuses. In publicly traded companies th ...

and expansion of educational opportunities using trade and industrial schools, he was an avowed opponent of the nascent socialist movement

The history of socialism has its origins in the 1789 French Revolution and the changes which it brought, although it has precedents in earlier movements and ideas. ''The Communist Manifesto'' was written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1847-4 ...

and published critiques of Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

's popular novel ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short o ...

''.

Henry George debates

Beginning in 1879, Walker and the political economistHenry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

engaged in a prominent debate over economic rent

In economics, economic rent is any payment (in the context of a market transaction) to the owner of a factor of production in excess of the cost needed to bring that factor into production. In classical economics, economic rent is any payment ...

s, land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various isla ...

, money, and taxes. Based on a series of lectures delivered at Harvard, Walker published his ''Land and Its Rent'' in 1883 as a criticism of George's 1879 ''Progress and Poverty

''Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy'' is an 1879 book by social theorist and economist Henry George. It is a treatise on the questions of why pover ...

''. Walker's position on international bimetallism influenced his arguments that the primary cause of economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economical downturn that is result of lowered economic activity in one major or more national economies. Economic depression maybe related to one specific country were there is some economic ...

s was not land speculation, but rather constriction of the money supply. Walker also criticized George's assumptions that technical progress was always labor saving and whether land held for speculation was unproductive or inefficient.

Bimetallism

In August 1878, Walker represented the United States at the thirdInternational Monetary Conference The international monetary conferences were a series of assemblies held in the second half of the 19th century. They were held with a view to reaching agreement on matters relating to international relationships between national currency systems.

B ...

in Paris while also attending the 1878 Exposition. Not only were the attempts by the United States to re-establish an international silver standard

The silver standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is a fixed weight of silver. Silver was far more widespread than gold as the monetary standard worldwide, from the Sumerians 3000 BC until 1873. Following ...

defeated, but Walker also had to scramble to complete the report on the Exposition in only four days. Although he returned to the U.S. in October disheartened by the failure of the conference and exhausted by his obligations at the Exposition, the trip had secured Walker a commanding national and international reputation.

Walker published ''International Bimetallism'' in 1896 roundly critiquing the demonetization of silver out of political pressure and the impact of this change on prices and profits as well as worker employment and wages. Walker's reputation and position on the issue isolated him among public figures and made him a target in the press. The book was published in the midst of the 1896 presidential election pitting populist "silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

" candidate William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

against the capitalist "gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

" candidate William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

and the competing interpretations of the nation's leading economist's stance on the issue became a political football during the campaign. The presidential candidate and economist were not close allies as Walker advocated a double standard by all leading financial nations while Bryan argued for the United States' unilateral shift to a silver standard. The rift was heightened by the east-west divide on the issue as well as Walker's general distaste for political populism; Walker's position was supported by conservative bankers and statesmen like Henry Lee Higginson

Henry Lee Higginson (November 18, 1834 – November 14, 1919) was an American businessman best known as the founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and a patron of Harvard University.

Biography

Higginson was born in New York City on November 18 ...

, George F. Hoar, John M. Forbes, and Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign polic ...

.

Other interests

''Political Economy'', the first edition published in 1883, was one of the most widely used textbooks of the 19th century as a component of the ''American Science Series''.Robert Solow

Robert Merton Solow, GCIH (; born August 23, 1924) is an American economist whose work on the theory of economic growth culminated in the exogenous growth model named after him. He is currently Emeritus Institute Professor of Economics at th ...

criticized the third edition (1888) for being devoid of facts, figures, and mostly full of off-the-cuff judgments on the practices and capacities of Native Americans and immigrants, but generally embodying the state of the art of economics at the time.

Walker also took an interest in demographics later in his career, particularly towards the issues of immigration and birth rates. He published ''The Growth of the United States'' in 1882 and ''Restriction on Immigration'' in 1896 arguing for increasing restrictions out of concern about the diminished industrial and intellectual capacity of the most recent wave of immigrants. Walker also argued that unrestricted immigration was the major reason behind nineteenth-century Native American fertility decline, but while the argument was politically popular and became widely accepted in mobilizing restrictions on immigration, it rested upon a surprisingly facile statistical analysis that was later refuted. Writing on immigrants from southern Italy, Hungary, Austria, and Russia in ''The Atlantic'', Walker claimed,

The entrance into our political, social, and industrial life of such vast masses of peasantry, degraded below our utmost conceptions, is a matter which no intelligent patriot can look upon without the gravest apprehension and alarm. These people have no history behind them which is of a nature to give encouragement. They have none of the inherited instincts and tendencies which made it comparatively easy to deal with the immigration of the olden time. They are beaten men from beaten races; representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence. Centuries are against them, as centuries were on the side of those who formerly came to us. They have none of the ideas and aptitudes which fit men to take up readily and easily the problem of self-care and self-government, such as belong to those who are descended from the tribes that met under the oak-trees of old Germany to make laws and choose chieftains.

MIT presidency

Established in 1861 and opened in 1865, the

Established in 1861 and opened in 1865, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

(MIT) saw its financial stability severely undermined following the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

and subsequent Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

. Seventy-five-year-old founder William Barton Rogers was elected interim president in 1878 after John Daniel Runkle stepped down. Rogers wrote Walker in June 1880 to offer him the Presidency, and Walker evidently debated the opportunity for some time as Rogers sent follow-up inquiries in January and February 1881 requesting his committed decision. Walker ultimately accepted in early May and was formally elected President by the MIT Corporation on May 25, 1881, resigning his Yale appointment in June and his Census directorship in November. However, the assassination attempt on President Garfield in July 1881 and the ensuing illness before Garfield's death in September upset Walker's transition and delayed his formal introduction to the faculty of MIT until November 5, 1881. On May 30, 1882, during Walker's first Commencement exercises, Rogers died mid-speech where his last words were famously "bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the seams. It ...

".

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the Lawrence Scientific School at

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. Given the choice between funding technological research at the oldest university in the nation, or at an independent and adolescent institution, potential benefactors were indifferent or even hostile to funding MIT's competing mission. Earlier overtures from Harvard President Charles William Eliot

Charles William Eliot (March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an American academic who was president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909the longest term of any Harvard president. A member of the prominent Eliot family of Boston, he transfor ...

towards consolidation of the two schools were rejected or disrupted by Rogers in 1870 and 1878. Despite his tenure at the analogous Sheffield School of Yale University, Walker remained committed to MIT's independence from a larger institution. Walker also repeatedly received overtures from Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Sen ...

to become the first president of his new university in Palo Alto, California

Palo Alto (; Spanish for "tall stick") is a charter city in the northwestern corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

The city was es ...

, but Walker remained committed to MIT owing to his Boston upbringing.

Aid and expansion

In light of the difficulties in raising capital for these expansions and despite MIT's privately endowed status, Walker and other members of the Corporation lobbied the Massachusetts legislature for a $200,000 grant to aid in the industrial development of the Commonwealth ($ in 2016 dollars). After intensive negotiations that called upon Walker's extensive connections and civic experience, in 1887 the legislature made a grant of $300,000 over two years to the Institute, which would lead to a total of $1.6 million in grants from the Commonwealth before the practice was discontinued in 1921. Walker sought to erect a new building to address the increasingly cramped conditions of the original

Walker sought to erect a new building to address the increasingly cramped conditions of the original Boylston Street

Boylston Street is a major east–west thoroughfare in the city of Boston, Massachusetts. The street begins in Boston's Chinatown neighborhood, forms the southern border of the Boston Public Garden and Boston Common, runs through Back Bay, and e ...

campus located near Copley Square

Copley Square , named for painter John Singleton Copley, is a public square in Boston's Back Bay neighborhood, bounded by Boylston Street, Clarendon Street, St. James Avenue, and Dartmouth Street. Prior to 1883 it was known as Art Square due to i ...

, in the increasingly fashionable and crowded Back Bay

Back Bay is an officially recognized neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, built on reclaimed land in the Charles River basin. Construction began in 1859, as the demand for luxury housing exceeded the availability in the city at the time, and t ...