Friedrich Nietzsche on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

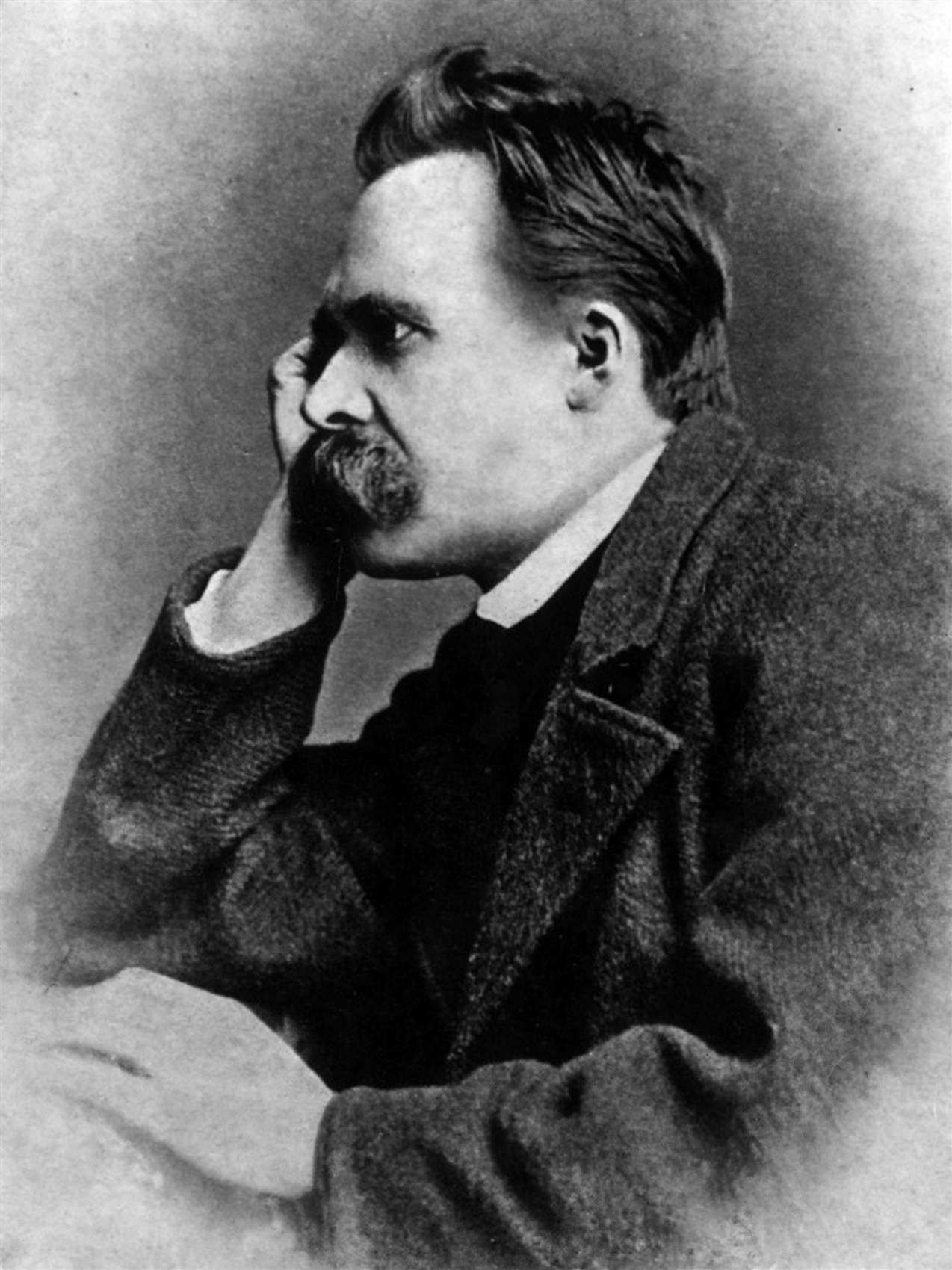

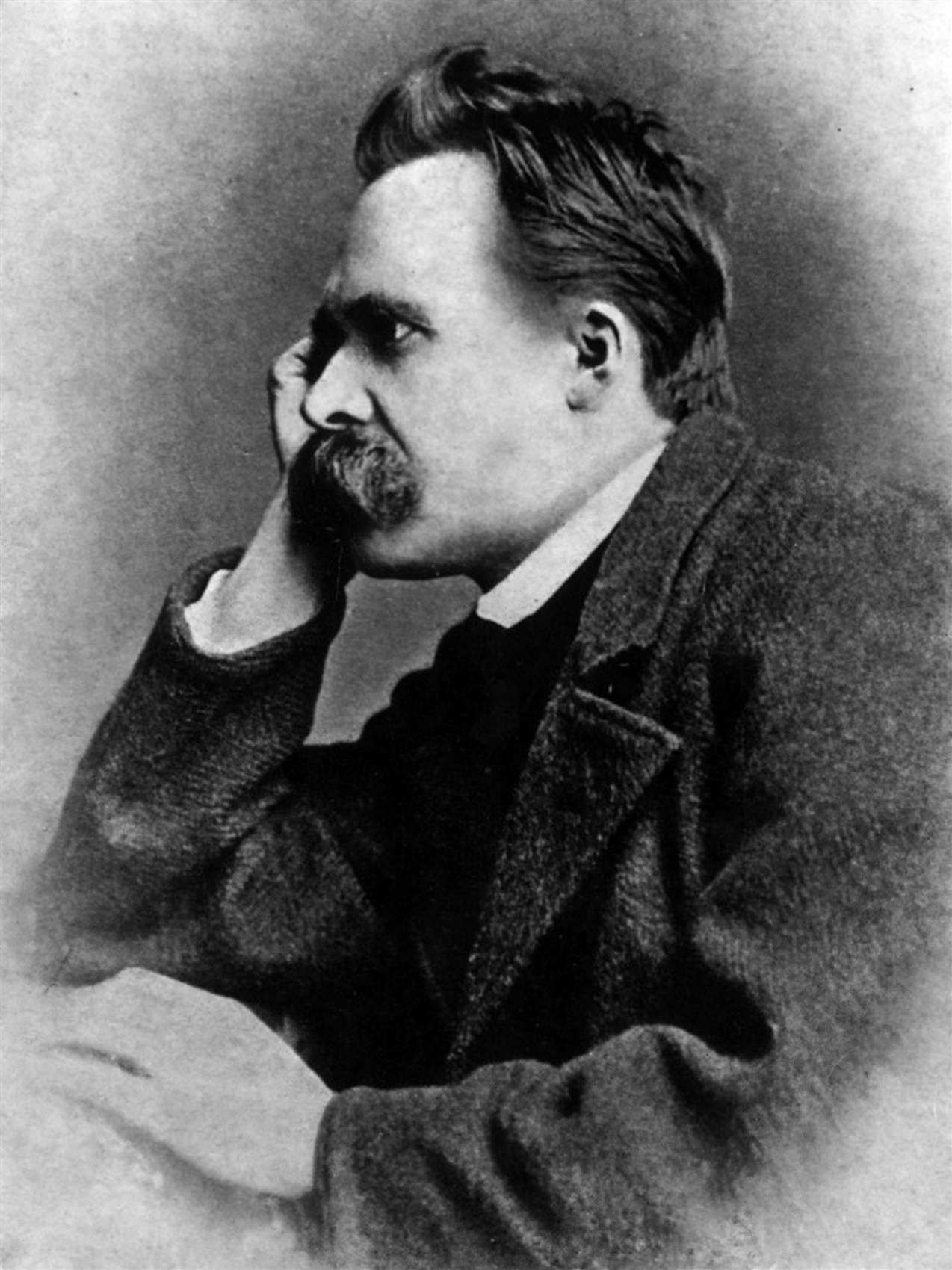

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche became the youngest professor to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the

Nietzsche attended a boys' school and then a private school, where he became friends with Gustav Krug and Wilhelm Pinder, both of whom came from highly respected families. Academic records from one of the schools attended by Nietzsche noted that he excelled in

Nietzsche attended a boys' school and then a private school, where he became friends with Gustav Krug and Wilhelm Pinder, both of whom came from highly respected families. Academic records from one of the schools attended by Nietzsche noted that he excelled in  After graduation in September 1864, Nietzsche began studying theology and classical philology at the

After graduation in September 1864, Nietzsche began studying theology and classical philology at the

In 1869, with Ritschl's support, Nietzsche received an offer to become a professor of

In 1869, with Ritschl's support, Nietzsche received an offer to become a professor of  In 1873 Nietzsche began to accumulate notes that would be posthumously published as '' Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks''. Between 1873 and 1876, he published four separate long essays: "

In 1873 Nietzsche began to accumulate notes that would be posthumously published as '' Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks''. Between 1873 and 1876, he published four separate long essays: "

Living on his pension from Basel along with aid from friends, Nietzsche travelled frequently to find climates more conducive to his health. He lived until 1889 as an independent author in different cities. He spent many summers in Sils Maria near St. Moritz in Switzerland, and many of his winters in the Italian cities of

Living on his pension from Basel along with aid from friends, Nietzsche travelled frequently to find climates more conducive to his health. He lived until 1889 as an independent author in different cities. He spent many summers in Sils Maria near St. Moritz in Switzerland, and many of his winters in the Italian cities of

University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

. Plagued by health problems for most of his life, he resigned from the university in 1879, and in the following decade he completed much of his core writing. In 1889, aged 44, he suffered a collapse and thereafter a complete loss of his mental faculties, with paralysis

Paralysis (: paralyses; also known as plegia) is a loss of Motor skill, motor function in one or more Skeletal muscle, muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory d ...

and vascular dementia

Vascular dementia is dementia caused by a series of strokes. Restricted blood flow due to strokes reduces oxygen and glucose delivery to the brain, causing cell injury and neurological deficits in the affected region. Subtypes of vascular dement ...

. He lived his remaining years under the care of his family until his death. His works and his philosophy have fostered not only extensive scholarship but also much popular interest.

Nietzsche's work encompasses philosophical polemic

Polemic ( , ) is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial to ...

s, poetry, cultural critic

A cultural critic is a critic of a given culture, usually as a whole. Cultural criticism has significant overlap with social and cultural theory. While such criticism is simply part of the self-consciousness of the culture, the social positions o ...

ism and fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying character (arts), individuals, events, or setting (narrative), places that are imagination, imaginary or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent ...

, while displaying a fondness for aphorisms

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tra ...

and irony

Irony, in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what, on the surface, appears to be the case with what is actually or expected to be the case. Originally a rhetorical device and literary technique, in modernity, modern times irony has a ...

. Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth

Truth or verity is the Property (philosophy), property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise cor ...

in favour of perspectivism

Perspectivism (also called perspectivalism) is the epistemological principle that perception of and knowledge of something are always bound to the interpretive perspectives of those observing it. While perspectivism regard all perspectives and ...

; a genealogical

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

critique of religion and Christian morality

Christian ethics, also known as moral theology, is a multi-faceted ethical system. It is a Virtue ethics, virtue ethic, which focuses on building moral character, and a Deontological ethics, deontological ethic which emphasizes duty according ...

and a related theory of master–slave morality; the aesthetic

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,'' , acces ...

affirmation of life in response to both the " death of God" and the profound crisis of nihilism

Nihilism () encompasses various views that reject certain aspects of existence. There have been different nihilist positions, including the views that Existential nihilism, life is meaningless, that Moral nihilism, moral values are baseless, and ...

; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces; and a characterisation of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power

The will to power () is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's ...

. He also developed influential concepts such as the ' and his doctrine of eternal return. In his later work he became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and moral mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. His body of work touched a wide range of topics, including art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

, philology

Philology () is the study of language in Oral tradition, oral and writing, written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also de ...

, history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

, music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

, tragedy

A tragedy is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a tragic hero, main character or cast of characters. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy is to invoke an accompanying catharsi ...

, culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

and science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, and drew inspiration from Greek tragedy as well as figures such as Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

, Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, minister, abolitionism, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalism, Transcendentalist movement of th ...

, Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influent ...

and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

.

After Nietzsche's death his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche

Therese Elisabeth Alexandra Förster-Nietzsche (10 July 1846 – 8 November 1935) was the sister of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the creator of the Nietzsche Archive in 1894.

Förster-Nietzsche was two years younger than her brother ...

, became the curator and editor of his manuscripts. She edited his unpublished writings to fit her German ultranationalist ideology, often contradicting or obfuscating Nietzsche's stated opinions, which were explicitly opposed to antisemitism and nationalism. Through her published editions, Nietzsche's work became associated with fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

and Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

. 20th-century scholars such as Walter Kaufmann, R. J. Hollingdale and Georges Bataille

Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille (; ; 10 September 1897 – 8 July 1962) was a French philosopher and intellectual working in philosophy, literature, sociology, anthropology, and history of art. His writing, which included essays, novels, ...

defended Nietzsche against this interpretation, and corrected editions of his writings were soon made available. Nietzsche's thought enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1960s and his ideas have since had a profound impact on 20th- and early-21st-century thinkers across philosophy—especially in schools of continental philosophy

Continental philosophy is a group of philosophies prominent in 20th-century continental Europe that derive from a broadly Kantianism, Kantian tradition.Continental philosophers usually identify such conditions with the transcendental subject or ...

such as existentialism

Existentialism is a family of philosophical views and inquiry that explore the human individual's struggle to lead an authentic life despite the apparent absurdity or incomprehensibility of existence. In examining meaning, purpose, and valu ...

, postmodernism

Postmodernism encompasses a variety of artistic, Culture, cultural, and philosophical movements that claim to mark a break from modernism. They have in common the conviction that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of depicting ...

and post-structuralism

Post-structuralism is a philosophical movement that questions the objectivity or stability of the various interpretive structures that are posited by structuralism and considers them to be constituted by broader systems of Power (social and poli ...

—as well as art, literature, music, poetry, politics and popular culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of cultural practice, practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art

.

f. pop art

F is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet.

F may also refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* F or f, the number 15 (number), 15 in hexadecimal and higher positional systems

* ''p'F'q'', the hypergeometric function

* F-distributi ...

or mass art, sometimes contraste ...Life

Youth (1844–1868)

Born on 15 October 1844, Nietzsche grew up in the town of Röcken (now part of Lützen), nearLeipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, in the Prussian Province of Saxony

The Province of Saxony (), also known as Prussian Saxony (), was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia and later the Free State of Prussia from 1816 until 1944. Its capital was Magdeburg.

It was formed by the merger of various territories ceded ...

. He was named after King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, who turned 49 on the day of Nietzsche's birth (Nietzsche later dropped his middle name, Wilhelm). Nietzsche's great-grandfather, (1714–1804), was an inspector and a philosopher. Nietzsche's grandfather, (1756–1826), was a theologian. Nietzsche's parents, Carl Ludwig Nietzsche (1813–1849), a Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

pastor and former teacher; and (''née'' Oehler) (1826–1897), married in 1843, the year before their son's birth. They had two other children: a daughter, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche

Therese Elisabeth Alexandra Förster-Nietzsche (10 July 1846 – 8 November 1935) was the sister of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the creator of the Nietzsche Archive in 1894.

Förster-Nietzsche was two years younger than her brother ...

, born in 1846; and a second son, Ludwig Joseph, born in 1848. Nietzsche's father died of a brain disease in 1849, after a year of excruciating agony, when the boy was only four years old; Ludwig Joseph died six months later at age two. The family then moved to Naumburg

Naumburg () is a town in (and the administrative capital of) the district Burgenlandkreis, in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany. It has a population of around 33,000. The Naumburg Cathedral became a UNES ...

, where they lived with Nietzsche's maternal grandmother and his father's two unmarried sisters. After the death of Nietzsche's grandmother in 1856, the family moved into their own house, now Nietzsche-Haus, a museum, and Nietzsche study centre.

Nietzsche attended a boys' school and then a private school, where he became friends with Gustav Krug and Wilhelm Pinder, both of whom came from highly respected families. Academic records from one of the schools attended by Nietzsche noted that he excelled in

Nietzsche attended a boys' school and then a private school, where he became friends with Gustav Krug and Wilhelm Pinder, both of whom came from highly respected families. Academic records from one of the schools attended by Nietzsche noted that he excelled in Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

.

In 1854 he began to attend the Domgymnasium in Naumburg. Because his father had worked for the state (as a pastor), the now-fatherless Nietzsche was offered a scholarship to study at the internationally recognised Schulpforta. The claim that Nietzsche was admitted on the strength of his academic competence has been debunked: his grades were not near the top of the class. He studied there from 1858 to 1864, becoming friends with Paul Deussen

Paul Jakob Deussen (; 7 January 1845 – 6 July 1919) was a German Indologist and professor of philosophy at University of Kiel. Strongly influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer, Deussen was a friend of Friedrich Nietzsche and Swami Vivekananda. In ...

and Carl von Gersdorff (1844–1904), who later became a jurist. He also found time to work on poems and musical compositions. Nietzsche led "Germania", a music and literature club, during his summers in Naumburg. At Schulpforta, Nietzsche received an important grounding in languages—Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, and French—to be able to read important primary source

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called an original source) is an Artifact (archaeology), artifact, document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, recording, or any other source of information that was cre ...

s; he also experienced for the first time being away from his family life in a small-town conservative environment. His end-of-semester exams in March 1864 showed a 1 in Religion and German; a 2a in Greek and Latin; a 2b in French, History, and Physics; and a "lackluster" 3in Hebrew and Mathematics.

Nietzsche was an amateur composer. He composed several works for voice, piano, and violin beginning in 1858 at the Schulpforta in Naumburg when he started to work on musical compositions. Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

was dismissive of Nietzsche's music, allegedly mocking a birthday gift of a piano composition sent by Nietzsche in 1871 to Wagner's wife Cosima. German conductor and pianist Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (; 8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for establishi ...

also described another of Nietzsche's pieces as "the most undelightful and the most anti-musical draft on musical paper that I have faced in a long time".

While at Schulpforta Nietzsche pursued subjects that were considered unbecoming. He became acquainted with the work of the then-almost-unknown poet Friedrich Hölderlin, calling him "my favourite poet" and writing an essay in which he said that the poet raised consciousness to "the most sublime ideality". The teacher who corrected the essay gave it a good mark but commented that Nietzsche should concern himself in the future with healthier, more lucid, and more "German" writers. Additionally, he became acquainted with Ernst Ortlepp, an eccentric, blasphemous

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

, and often drunken poet who was found dead in a ditch weeks after meeting the young Nietzsche but who may have introduced Nietzsche to the music and writing of Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

. Perhaps under Ortlepp's influence, he and a student named Richter returned to school drunk and encountered a teacher, resulting in Nietzsche's demotion from first in his class and the end of his status as a prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect' ...

.

After graduation in September 1864, Nietzsche began studying theology and classical philology at the

After graduation in September 1864, Nietzsche began studying theology and classical philology at the University of Bonn

The University of Bonn, officially the Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn (), is a public research university in Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was founded in its present form as the () on 18 October 1818 by Frederick Willi ...

in the hope of becoming a minister. For a short time, he and Deussen became members of the Burschenschaft '' Frankonia''. After one semester (and to the anger of his mother), he stopped his theological studies and lost his faith. As early as his 1862 essay "Fate and History", Nietzsche argued that historical research had discredited the central teachings of Christianity, but David Strauss

David Friedrich Strauss (; ; 27 January 1808 – 8 February 1874) was a German liberal Protestant theologian and writer, who influenced Christian Europe with his portrayal of the "historical Jesus", whose divine nature he explored via myth. St ...

's ''Life of Jesus

The life of Jesus is primarily outlined in the four canonical gospels, which includes his Genealogy of Jesus, genealogy and Nativity of Jesus, nativity, Ministry of Jesus, public ministry, Passion of Jesus, passion, prophecy, Resurrection of J ...

'' also seems to have had a profound effect on the young man. In addition, Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; ; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book '' The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced ge ...

's '' The Essence of Christianity'' influenced young Nietzsche with its argument that people created God and not the other way around. In June 1865, at the age of 20, Nietzsche wrote to his sister Elisabeth, who was deeply religious, a letter regarding his loss of faith. This letter contains the following statement:

Hence the ways of men part: if you wish to strive for peace of soul and pleasure, then believe; if you wish to be a devotee of truth, then inquire....Nietzsche subsequently concentrated on studying philology under Professor Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl, whom he followed to the

University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December 1409 by Frederick I, Electo ...

in 1865. There, he became close friends with his fellow-student Erwin Rohde. Nietzsche's first philological publications appeared soon after.

In 1865 Nietzsche thoroughly studied the works of Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

. He owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading Schopenhauer's ''The World as Will and Representation

''The World as Will and Representation'' (''WWR''; , ''WWV''), sometimes translated as ''The World as Will and Idea'', is the central work of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. The first edition was published in late 1818, with the date ...

,'' later admitting that Schopenhauer was one of the few thinkers whom he respected, dedicating the essay "Schopenhauer as Educator

''Untimely Meditations'' (), also translated as ''Unfashionable Observations'' and ''Thoughts Out of Season'', consists of four works by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, started in 1873 and completed in 1876.

The work comprises a collection ...

" in the '' Untimely Meditations'' to him.

In 1866 he read Friedrich Albert Lange's '' History of Materialism''. Lange's descriptions of Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

's anti-materialistic philosophy, the rise of European Materialism

Materialism is a form of monism, philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental Substance theory, substance in nature, and all things, including mind, mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. Acco ...

, Europe's increased concern with science, Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

and the general rebellion against tradition and authority intrigued Nietzsche greatly. Nietzsche would ultimately argue the impossibility of an evolutionary explanation of the human aesthetic sense.

In 1867 Nietzsche signed up for one year of voluntary service with the Prussian artillery division in Naumburg. He was regarded as one of the finest riders among his fellow-recruits, and his officers predicted that he would soon reach the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

. However, in March 1868, while mounting his horse, Nietzsche struck his chest against the pommel and tore two muscles in his left side, leaving him exhausted and unable to walk for months. Consequently, he turned his attention to his studies again, completing them in 1868. Nietzsche also met Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

for the first time later that year.

Professor at Basel (1869–1879)

classical philology

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek and Roman literature and their original languages, ...

at the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

in Switzerland. He was only 24 years old and had neither completed his doctorate nor received a teaching certificate ("''habilitation

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in Germany, France, Italy, Poland and some other European and non-English-speaking countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excelle ...

''"). He was awarded an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

by Leipzig University

Leipzig University (), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December 1409 by Frederick I, Electo ...

in March 1869, again with Ritschl's support.

Despite his offer coming at a time when he was considering giving up philology for science, he accepted. To this day, Nietzsche is still among the youngest of the tenured Classics professors on record.

Nietzsche's 1870 projected doctoral thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

, "Contribution toward the Study and the Critique of the Sources of Diogenes Laertius" ("''Beiträge zur Quellenkunde und Kritik des Laertius Diogenes''"), examined the origins of the ideas of Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

. Though never submitted, it was later published as a ('congratulatory publication') in Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

.

Before moving to Basel Nietzsche renounced his Prussian citizenship: for the rest of his life he remained officially stateless.

Nevertheless, Nietzsche served in the Prussian forces during the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

(1870–1871) as a medical orderly. In his short time in the military, he experienced much and witnessed the traumatic effects of battle. He also contracted diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacteria, bacterium ''Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild Course (medicine), clinical course, but in some outbreaks, the mortality rate approaches 10%. Signs a ...

and dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

. Walter Kaufmann speculates that he also contracted syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

at a brothel along with his other infections at this time. On returning to Basel in 1870, Nietzsche observed the establishment of the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

and Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

's subsequent policies as an outsider and with a degree of scepticism regarding their genuineness. His inaugural lecture at the university was " Homer and Classical Philology". Nietzsche also met Franz Overbeck, a professor of theology who remained his friend throughout his life. Afrikan Spir, a little-known Russian philosopher responsible for the 1873 ''Thought and Reality'' and Nietzsche's colleague, the historian Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (; ; 25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. His best known work is '' The Civilization of the Renaissance in ...

, whose lectures Nietzsche frequently attended, began to exercise significant influence on him.

Nietzsche had already met Richard Wagner in Leipzig in 1868 and later Wagner's wife, Cosima. Nietzsche admired both greatly and during his time at Basel frequently visited Wagner's house in Tribschen in Lucerne

Lucerne ( ) or Luzern ()Other languages: ; ; ; . is a city in central Switzerland, in the Languages of Switzerland, German-speaking portion of the country. Lucerne is the capital of the canton of Lucerne and part of the Lucerne (district), di ...

. The Wagners brought Nietzsche into their most intimate circle—which included Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic music, Romantic period. With a diverse List of compositions by Franz Liszt, body of work spanning more than six ...

, of whom Nietzsche colloquially described: "Liszt or the art of running after women!" Nietzsche enjoyed the attention he gave to the beginning of the Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival () is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of stage works by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived and promoted the idea of a special ...

. In 1870 he gave Cosima Wagner the manuscript of "The Genesis of the Tragic Idea" as a birthday gift. In 1872 Nietzsche published his first book, '' The Birth of Tragedy''. However, his colleagues within his field, including Ritschl, expressed little enthusiasm for the work in which Nietzsche eschewed the classical philologic method in favour of a more speculative approach. In his polemic

Polemic ( , ) is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial to ...

''Philology of the Future'', Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff damped the book's reception and increased its notoriety. In response, Rohde (then a professor in Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

) and Wagner came to Nietzsche's defence. Nietzsche remarked freely about the isolation he felt within the philological community and attempted unsuccessfully to transfer to a position in philosophy at Basel.

In 1873 Nietzsche began to accumulate notes that would be posthumously published as '' Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks''. Between 1873 and 1876, he published four separate long essays: "

In 1873 Nietzsche began to accumulate notes that would be posthumously published as '' Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks''. Between 1873 and 1876, he published four separate long essays: "David Strauss

David Friedrich Strauss (; ; 27 January 1808 – 8 February 1874) was a German liberal Protestant theologian and writer, who influenced Christian Europe with his portrayal of the "historical Jesus", whose divine nature he explored via myth. St ...

: the Confessor and the Writer", " On the Use and Abuse of History for Life", "Schopenhauer as Educator", and "Richard Wagner in Bayreuth". These four later appeared in a collected edition under the title '' Untimely Meditations''. The essays shared the orientation of a cultural critique, challenging the developing German culture suggested by Schopenhauer and Wagner. During this time in the circle of the Wagners, he met Malwida von Meysenbug and Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (; 8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for establishi ...

. He also began a friendship with Paul Rée who, in 1876, influenced him into dismissing the pessimism

Pessimism is a mental attitude in which an undesirable outcome is anticipated from a given situation. Pessimists tend to focus on the negatives of life in general. A common question asked to test for pessimism is "Is the glass half empty or half ...

in his early writings. However, he was deeply disappointed by the Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival () is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of stage works by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived and promoted the idea of a special ...

of 1876, where the banality of the shows and baseness of the public repelled him. He was also alienated by Wagner's championing of "German culture", which Nietzsche felt a contradiction in terms, as well as by Wagner's celebration of his fame among the German public. All this contributed to his subsequent decision to distance himself from Wagner.

With the publication in 1878 of '' Human, All Too Human'' (a book of aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tra ...

s ranging from metaphysics to morality to religion), a new style of Nietzsche's work became clear, highly influenced by Afrikan Spir's ''Thought and Reality'' and reacting against the pessimistic philosophy of Wagner and Schopenhauer. Nietzsche's friendship with Deussen and Rohde cooled as well. In 1879, after a significant decline in health, Nietzsche had to resign his position at Basel and was pensioned. Since his childhood, various disruptive illnesses had plagued him, including moments of shortsightedness that left him nearly blind, migraine

Migraine (, ) is a complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea, and light and sound sensitivity. Other characterizing symptoms may includ ...

headaches, and violent indigestion. The 1868 riding accident and diseases in 1870 may have aggravated these persistent conditions, which continued to affect him through his years at Basel, forcing him to take longer and longer holidays until regular work became impractical.

Independent philosopher (1879–1888)

Living on his pension from Basel along with aid from friends, Nietzsche travelled frequently to find climates more conducive to his health. He lived until 1889 as an independent author in different cities. He spent many summers in Sils Maria near St. Moritz in Switzerland, and many of his winters in the Italian cities of

Living on his pension from Basel along with aid from friends, Nietzsche travelled frequently to find climates more conducive to his health. He lived until 1889 as an independent author in different cities. He spent many summers in Sils Maria near St. Moritz in Switzerland, and many of his winters in the Italian cities of Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Rapallo

Rapallo ( , , ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, in the Italy, Italian region of Liguria.

As of 2017 it had 29,778 inhabitants. It lies on the Ligurian Sea coast, on the Tigullio Gulf, between Portofino and ...

, and Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, and the French city of Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionFrance occupied Tunisia, he planned to travel to  By 1882 Nietzsche was taking huge doses of

By 1882 Nietzsche was taking huge doses of

On 3 January 1889 Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown. Two policemen approached him after he caused a public disturbance in the streets of

On 3 January 1889 Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown. Two policemen approached him after he caused a public disturbance in the streets of  On 6 January 1889 Burckhardt showed the letter he had received from Nietzsche to Overbeck. The following day, Overbeck received a similar letter and decided that Nietzsche's friends had to bring him back to Basel. Overbeck travelled to Turin and brought Nietzsche to a psychiatric clinic in Basel. By that time Nietzsche appeared fully in the grip of a serious mental illness, and his mother Franziska decided to transfer him to a clinic in

On 6 January 1889 Burckhardt showed the letter he had received from Nietzsche to Overbeck. The following day, Overbeck received a similar letter and decided that Nietzsche's friends had to bring him back to Basel. Overbeck travelled to Turin and brought Nietzsche to a psychiatric clinic in Basel. By that time Nietzsche appeared fully in the grip of a serious mental illness, and his mother Franziska decided to transfer him to a clinic in  Nietzsche's insanity was originally diagnosed as tertiary syphilis, in accordance with a prevailing medical paradigm of the time. Although most commentators regard his breakdown as unrelated to his philosophy,

Nietzsche's insanity was originally diagnosed as tertiary syphilis, in accordance with a prevailing medical paradigm of the time. Although most commentators regard his breakdown as unrelated to his philosophy,

A trained philologist, Nietzsche had a thorough knowledge of

A trained philologist, Nietzsche had a thorough knowledge of

Albert Fouillée, ''Revue philosophique de la France et de l'étranger''. An. 34. Paris 1909. T. 67, S. 519–525 (on French Wikisource) The essays of

* '' The Birth of Tragedy'' (1872)

* ''

* '' The Birth of Tragedy'' (1872)

* ''

Public Opinions, Private Laziness: The Epistemological Break in Nietzsche

''Numero Cinq'' magazine (August). * * * * Conway, Daniel (Ed.),

Nietzsche and the Political

' (Routledge, 1997) * Corriero, Emilio Carlo, ''Nietzsche oltre l'abisso. Declinazioni italiane della 'morte di Dio, Marco Valerio, Torino, 2007 * Corriero, Emilio Carlo, "Nietzsche's Death of God and Italian Philosophy". Preface by Gianni Vattimo, Rowman & Littlefield, London & New York, 2016 * Dod, Elmar, "Der unheimlichste Gast. Die Philosophie des Nihilismus". Marburg: Tectum Verlag 2013. . "Der unheimlichste Gast wird heimisch. Die Philosophie des Nihilismus – Evidenzen der Einbildungskraft". (Wissenschaftliche Beiträge Philosophie Bd. 32) Baden–Baden 2019 * * * Garrard, Graeme (2008). "Nietzsche For and Against the Enlightenment," ''Review of Politics'', Vol. 70, No. 4, pp. 595–608. * * Golan, Zev. ''God, Man, and Nietzsche: A Startling Dialogue between Judaism and Modern Philosophers'' (iUniverse, 2007). * * * Huskinson, Lucy. ''Nietzsche and Jung: The whole self in the union of opposites'' (London and New York: Routledge, 2004) * Kaplan, Erman. ''Cosmological Aesthetics through the Kantian Sublime and Nietzschean Dionysian''. Lanham: UPA, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. * * Kopić, Mario, ''S Nietzscheom o Europi'', Jesenski i Turk, Zagreb, 2001 * * * * * * * * * * O'Flaherty, James C., Sellner, Timothy F., Helm, Robert M., ''Studies in Nietzsche and the Classical Tradition'' (

Review

Translation by Will Stone of ''Nietzsche en Italie'', Bernard Grasset, 1929. * Prideaux, Sue, '' I Am Dynamite! A Life of Nietzsche'' (

Nietzsche NOW!: The Great Immoralist on the Vital Issues of Our Time

', New York City: Warbler Press. * Weir, Simon & Hill Glen. (2021), "Making space for degenerate thinking: revaluing architecture with Friedrich Nietzsche." arq: architecture research quarterly 25:2

Making space for degenerate thinking: revaluing architecture with Friedrich Nietzsche

* * *

Entry on Nietzsche

at Britannica.com

Nietzsche's brief autobiography

* * * * * * ** ** * **

Nietzsche Source: Digital version of the German critical edition of the complete works and Digital facsimile edition of the entire Nietzsche estate

Lexido: Searchable Database index of Public Domain editions of all Nietzsche's major works

*

* Walter Kaufmann 1960 ttps://archive.org/details/NietzscheAndTheCrisisInPhilosophy Prof. Nietzsche and the Crisis in Philosophy(audio) * * Burkhart Brückner, Robin Pape

Biography of Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

in

Biographical Archive of Psychiatry (BIAPSY)

* * Rick Roderick (1991

Nietzsche and the Postmodern Condition (1991)

Video Lectures {{DEFAULTSORT:Nietzsche, Friedrich 1844 births 1900 deaths People from Lützen People from the Province of Saxony Former Lutherans 19th-century German non-fiction writers 19th-century German male writers 19th-century German novelists 19th-century German philosophers 19th-century German male musicians 19th-century Prussian people Aphorists German critics of Christianity Determinists Existentialists German classical philologists Hellenists German metaphysicians German philosophers of art Philosophers of time German philosophy writers Writers from Saxony-Anhalt Leipzig University alumni University of Bonn alumni Academic staff of the University of Basel People associated with the University of Basel Prussian Army personnel German military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War Deaths from pneumonia in Germany Dithyrambic poets

Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

to view Europe from the outside but later abandoned that idea, probably for health reasons. Nietzsche occasionally returned to Naumburg to visit his family, and, especially during this time, he and his sister, Elisabeth, had repeated periods of conflict and reconciliation.

While in Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Nietzsche's failing eyesight prompted him to explore the use of typewriter

A typewriter is a Machine, mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of Button (control), keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an i ...

s as a means of continuing to write. He is known to have tried using the Hansen Writing Ball, a contemporary typewriter device. In the end, a past pupil of his, Peter Gast, became a private secretary to Nietzsche. In 1876, Gast transcribed the crabbed, nearly illegible handwriting of Nietzsche's first time with Richard Wagner in Bayreuth. He subsequently transcribed and proofread the galleys for almost all of Nietzsche's work. On at least one occasion, on 23 February 1880, the usually poor Gast received 200 marks from their mutual friend, Paul Rée. Gast was one of the very few friends Nietzsche allowed to criticise him. In responding most enthusiastically to '' Also Sprach Zarathustra'' ("Thus Spoke Zarathustra"), Gast did feel it necessary to point out that what were described as "superfluous" people were in fact quite necessary. He went on to list the number of people Epicurus

Epicurus (, ; ; 341–270 BC) was an Greek philosophy, ancient Greek philosopher who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy that asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain tranqui ...

, for example, had to rely on to supply his simple diet of goat cheese.

To the end of his life, Gast and Overbeck remained consistently faithful friends. Malwida von Meysenbug remained like a motherly patron even outside the Wagner circle. Soon Nietzsche made contact with the music-critic Carl Fuchs. Nietzsche stood at the beginning of his most productive period. Beginning with '' Human, All Too Human'' in 1878, Nietzsche published one book or major section of a book each year until 1888, his last year of writing; that year, he completed five.

In 1882 Nietzsche published the first part of ''The Gay Science

''The Gay Science'' (; sometimes translated as ''The Joyful Wisdom'' or ''The Joyous Science'') is a book by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1882, and followed by a second edition in 1887 after the completion of ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' and ...

''. That year he also met Lou Andreas-Salomé

Lou Andreas-Salomé (born either Louise von Salomé or Luíza Gustavovna Salomé or Lioulia von Salomé, ; 12 February 1861 – 5 February 1937) was a Russian-born psychoanalyst and a well-traveled author, narrator, and essayist from a French Hu ...

, through Malwida von Meysenbug and Paul Rée.

Salomé's mother took her to Rome when Salomé was 21. At a literary salon in the city, Salomé became acquainted with Paul Rée. Rée proposed marriage to her, but she, instead, proposed that they should live and study together as "brother and sister", along with another man for company, where they would establish an academic commune. Rée accepted the idea and suggested that they be joined by his friend Nietzsche. The two met Nietzsche in Rome in April 1882, and Nietzsche is believed to have instantly fallen in love with Salomé, as Rée had done. Nietzsche asked Rée to propose marriage to Salomé, which she rejected. She had been interested in Nietzsche as a friend, but not as a husband. Nietzsche nonetheless was content to join with Rée and Salomé touring through Switzerland and Italy together, planning their commune. The three travelled with Salomé's mother through Italy and considered where they would set up their "Winterplan" commune. They intended to set up their commune in an abandoned monastery, but no suitable location was found. On 13 May, in Lucerne, when Nietzsche was alone with Salomé, he earnestly proposed marriage to her again, which she rejected. He nonetheless was happy to continue with the plans for an academic commune. After discovering the relationship, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth became determined to get Nietzsche away from the "immoral woman". Nietzsche and Salomé spent the summer together in Tautenburg in Thuringia, often with Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth as a chaperone. Salomé reports that he asked her to marry him on three separate occasions and that she refused, though the reliability of her reports of events is questionable. Arriving in Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

(Germany) in October, Salomé and Rée separated from Nietzsche after a falling-out between Nietzsche and Salomé, in which Salomé believed that Nietzsche was desperately in love with her.

While the three spent a number of weeks together in Leipzig in October 1882, the following month Rée and Salomé left Nietzsche, leaving for Stibbe (modern-day Zdbowo in Poland) without any plans to meet again. Nietzsche soon fell into a period of mental anguish, although he continued to write to Rée, stating "We shall see one another from time to time, won't we?" In later recriminations, Nietzsche would blame on separate occasions the failure in his attempts to woo Salomé on Salomé, Rée, and on the intrigues of his sister (who had written letters to the families of Salomé and Rée to disrupt the plans for the commune). Nietzsche wrote of the affair in 1883, that he now felt "genuine hatred for my sister".

Amidst renewed bouts of illness, living in near-isolation after a falling out with his mother and sister regarding Salomé, Nietzsche fled to Rapallo, where he wrote the first part of ''Also Sprach Zarathustra'' in only ten days.

By 1882 Nietzsche was taking huge doses of

By 1882 Nietzsche was taking huge doses of opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

and continued to have trouble sleeping. In 1883, while staying in Nice, he was writing out his own prescriptions for the sedative chloral hydrate

Chloral hydrate is a geminal diol with the formula . It was first used as a sedative and hypnotic in Germany in the 1870s. Over time it was replaced by safer and more effective alternatives but it remained in use in the United States until at ...

, signing them "Dr. Nietzsche".

He turned away from the influence of Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

, and after he severed his social ties with Wagner, Nietzsche had few remaining friends. Now, with the new style of ''Zarathustra'', his work became even more alienating, and the market received it only to the degree required by politeness. Nietzsche recognised this and maintained his solitude, though he often complained. His books remained largely unsold. In 1885, he printed only 40 copies of the fourth part of ''Zarathustra'' and distributed a fraction of them among close friends, including Helene von Druskowitz.

In 1883 he tried and failed to obtain a lecturing post at the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December 1409 by Frederick I, Electo ...

. According to a letter he wrote to Peter Gast, this was due to his "attitude towards Christianity and the concept of God".

In 1886 Nietzsche broke with his publisher Ernst Schmeitzner, disgusted by his antisemitic opinions. Nietzsche saw his own writings as "completely buried and in this anti-Semitic dump" of Schmeitzner—associating the publisher with a movement that should be "utterly rejected with cold contempt by every sensible mind". He then printed ''Beyond Good and Evil

''Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future'' () is a book by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche that covers ideas in his previous work ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' but with a more polemical approach. It was first published in 1886 ...

'' at his own expense. He also acquired the publication rights for his earlier works and over the next year issued second editions of ''The Birth of Tragedy'', '' Human, All Too Human'', '' Daybreak'', and of ''The Gay Science

''The Gay Science'' (; sometimes translated as ''The Joyful Wisdom'' or ''The Joyous Science'') is a book by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1882, and followed by a second edition in 1887 after the completion of ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' and ...

'' with new prefaces placing the body of his work in a more coherent perspective. Thereafter, he saw his work as completed for a time and hoped that soon a readership would develop. In fact, interest in Nietzsche's thought did increase at this time, if rather slowly and imperceptibly to him. During these years Nietzsche met Meta von Salis, Carl Spitteler and Gottfried Keller.

In 1886 his sister, Elisabeth, married the antisemite Bernhard Förster and travelled to Paraguay to found Nueva Germania, a "Germanic" colony. Through correspondence, Nietzsche's relationship with Elisabeth continued through cycles of conflict and reconciliation, but they met again only after his collapse. He continued to have frequent and painful attacks of illness, which made prolonged work impossible.

In 1887 Nietzsche wrote the polemic '' On the Genealogy of Morality''. During the same year, he encountered the work of Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

, to whom he felt an immediate kinship. He also exchanged letters with Hippolyte Taine

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine (21 April 1828 – 5 March 1893) was a French historian, critic and philosopher. He was the chief theoretical influence on French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism and one of the first practitione ...

and Georg Brandes. Brandes, who had started to teach the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard ( , ; ; 5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danes, Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical tex ...

in the 1870s, wrote to Nietzsche asking him to read Kierkegaard, to which Nietzsche replied that he would come to Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

and read Kierkegaard with him. However, before fulfilling this promise, Nietzsche slipped too far into illness. At the beginning of 1888, Brandes delivered in Copenhagen one of the first lectures on Nietzsche's philosophy.

Although Nietzsche had previously announced at the end of '' On the Genealogy of Morality'' a new work with the title ''The Will to Power

The will to power () is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's ...

: Attempt at a Revaluation of All Values'', he seems to have abandoned this idea and, instead, used some of the draft passages to compose '' Twilight of the Idols'' and '' The Antichrist'' in 1888.

His health improved and he spent the summer in high spirits. In the autumn of 1888, his writings and letters began to reveal a higher estimation of his own status and "fate". He overestimated the increasing response to his writings, however, especially to the recent polemic, '' The Case of Wagner''. On his 44th birthday, after completing ''Twilight of the Idols'' and ''The Antichrist'', he decided to write the autobiography '' Ecce Homo''. In its preface—which suggests Nietzsche was well aware of the interpretive difficulties his work would generate—he declares, "Hear me! For I am such and such a person. Above all, do not mistake me for someone else." In December, Nietzsche began a correspondence with August Strindberg

Johan August Strindberg (; ; 22 January 184914 May 1912) was a Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist, and painter.Lane (1998), 1040. A prolific writer who often drew directly on his personal experience, Strindberg wrote more than 60 pla ...

and thought that, short of an international breakthrough, he would attempt to buy back his older writings from the publisher and have them translated into other European languages. Moreover, he planned the publication of the compilation '' Nietzsche contra Wagner'' and of the poems that made up his collection '' Dionysian-Dithyrambs''.

Mental illness and death (1889–1900)

On 3 January 1889 Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown. Two policemen approached him after he caused a public disturbance in the streets of

On 3 January 1889 Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown. Two policemen approached him after he caused a public disturbance in the streets of Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

. What happened remains unknown, but an often-repeated tale from shortly after his death states that Nietzsche witnessed the flogging of a horse at the other end of the Piazza Carlo Alberto, ran to the horse, threw his arms around its neck to protect it and then collapsed to the ground. In the following few days Nietzsche sent short writings—known as the ''Wahnzettel'' or ''Wahnbriefe'' (literally "Delusion notes" or "letters")—to a number of friends including Cosima Wagner

Francesca Gaetana Cosima Wagner (; 24 December 1837 – 1April 1930) was the daughter of the Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt and Franco-German romantic author Marie d'Agoult. She became the second wife of the German composer Richard ...

and Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (; ; 25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. His best known work is '' The Civilization of the Renaissance in ...

. Most of them were signed "Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; ) is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus ( or ; ...

", though some were also signed "der Gekreuzigte" meaning "the crucified one". To his former colleague Burckhardt, Nietzsche wrote:I have hadAdditionally, he commanded the German emperor to go to Rome to be shot and summoned the European powers to take military action against Germany, writing also that the pope should be put in jail and that he, Nietzsche, created the world and was in the process of having all antisemites shot dead.Caiaphas Joseph ben Caiaphas (; c. 14 BC – c. 46 AD) was the High Priest of Israel during the first century. In the New Testament, the Gospels of Gospel of Matthew, Matthew, Gospel of Luke, Luke and Gospel of John, John indicate he was an organizer of ...put in fetters. Also, last year I was crucified by the German doctors in a very drawn-out manner. Wilhelm, Bismarck, and all anti-Semites abolished.

Jena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

under the direction of Otto Binswanger. In January 1889, they proceeded with the planned release of '' Twilight of the Idols'', by that time already printed and bound. From November 1889 to February 1890, the art historian Julius Langbehn attempted to cure Nietzsche, claiming that the methods of the medical doctors were ineffective in treating Nietzsche's condition. Langbehn assumed progressively greater control of Nietzsche until his secretiveness discredited him. In March 1890, Franziska removed Nietzsche from the clinic and, in May 1890, brought him to her home in Naumburg. During this process Overbeck and Gast contemplated what to do with Nietzsche's unpublished works. In February they ordered a fifty-copy private edition of '' Nietzsche contra Wagner'', but the publisher C. G. Naumann secretly printed one hundred. Overbeck and Gast decided to withhold publishing '' The Antichrist'' and '' Ecce Homo'' because of their more radical content. Nietzsche's reception and recognition enjoyed their first surge.

In 1893, Nietzsche's sister, Elisabeth, returned from Nueva Germania in Paraguay following the suicide of her husband. She studied Nietzsche's works and, piece by piece, took control of their publication. Overbeck was dismissed and Gast finally co-operated. After the death of Franziska in 1897, Nietzsche lived in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

, where Elisabeth cared for him and allowed visitors, including Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (; 27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century ...

(who in 1895 had written ''Friedrich Nietzsche: A Fighter Against His Time'', one of the first books praising Nietzsche), to meet her uncommunicative brother. Elisabeth employed Steiner as a tutor to help her to understand her brother's philosophy. Steiner abandoned the attempt after only a few months, declaring that it was impossible to teach her anything about philosophy.

Georges Bataille

Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille (; ; 10 September 1897 – 8 July 1962) was a French philosopher and intellectual working in philosophy, literature, sociology, anthropology, and history of art. His writing, which included essays, novels, ...

wrote poetically of his condition ("'Man incarnate' must also go mad") and René Girard's postmortem psychoanalysis posits a worshipful rivalry with Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

. Girard suggests that Nietzsche signed his final letters as both Dionysus and the Crucified One because he was demonstrating that by being a god (Dionysus), one is also a victim (Crucified One) since a god still suffers by overcoming the law. Nietzsche had previously written, "All superior men who were irresistibly drawn to throw off the yoke of any kind of morality and to frame new laws had, if they were not actually mad, no alternative but to make themselves or pretend to be mad." (Daybreak, 14) The diagnosis of syphilis has since been challenged and a diagnosis of " manic-depressive illness with periodic psychosis

In psychopathology, psychosis is a condition in which a person is unable to distinguish, in their experience of life, between what is and is not real. Examples of psychotic symptoms are delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized or inco ...

followed by vascular dementia

Vascular dementia is dementia caused by a series of strokes. Restricted blood flow due to strokes reduces oxygen and glucose delivery to the brain, causing cell injury and neurological deficits in the affected region. Subtypes of vascular dement ...

" was put forward by Cybulska prior to Schain's study. Leonard Sax suggested the slow growth of a right-sided retro-orbital meningioma as an explanation of Nietzsche's dementia; Orth and Trimble postulated frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), also called frontotemporal degeneration disease or frontotemporal neurocognitive disorder, encompasses several types of dementia involving the progressive degeneration of the brain's frontal lobe, frontal and tempor ...

while other researchers have proposed a hereditary stroke disorder called CADASIL

CADASIL or CADASIL syndrome, involving cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, is the most common form of hereditary stroke disorder and is thought to be caused by mutations of the '' NOTCH3'' gen ...

. Poisoning by mercury, a treatment for syphilis at the time of Nietzsche's death, has also been suggested.

In 1898 and 1899 Nietzsche suffered at least two strokes. They partially paralysed him, leaving him unable to speak or walk. He likely suffered from clinical hemiparesis

Hemiparesis, also called unilateral paresis, is the weakness of one entire side of the body (''wikt:hemi-#Prefix, hemi-'' means "half"). Hemiplegia, in its most severe form, is the complete paralysis of one entire side of the body. Either hemipar ...

/hemiplegia on the left side of his body by 1899. After contracting pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

in mid-August 1900, he suffered another stroke during the night of 24–25 August and died at about noon on 25 August. Elisabeth had him buried beside his father at the church in Röcken near Lützen. His friend and secretary Gast gave his funeral oration, proclaiming: "Holy be your name to all future generations!"

Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche

Therese Elisabeth Alexandra Förster-Nietzsche (10 July 1846 – 8 November 1935) was the sister of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the creator of the Nietzsche Archive in 1894.

Förster-Nietzsche was two years younger than her brother ...

compiled ''The Will to Power

The will to power () is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's ...

'' from Nietzsche's unpublished notebooks and published it posthumously in 1901. Because his sister arranged the book based on her own conflation of several of Nietzsche's early outlines and took liberties with the material, the scholarly consensus has been that it does not reflect Nietzsche's intent. (For example, Elisabeth removed aphorism 35 of ''The Antichrist'', where Nietzsche rewrote a passage of the Bible.) Indeed, Mazzino Montinari, the editor of Nietzsche's ''Nachlass

''Nachlass'' (, older spelling ''Nachlaß'') is a German language, German word, used in academia to describe the collection of manuscripts, notes, correspondence, and so on left behind when a scholar dies. The word is a compound word, compound in ...

'', called it a forgery. Yet, the endeavour to rescue Nietzsche's reputation by discrediting ''The Will to Power'' often leads to scepticism about the value of his late notes, even of his whole ''Nachlass''. However, his ''Nachlass'' and ''The Will to Power'' are distinct.

Citizenship, nationality and ethnicity

General commentators and Nietzsche scholars, whether emphasising his cultural background or his language, overwhelmingly label Nietzsche as a "German philosopher." Others do not assign him a national category. While Germany had not yet been unified into a single sovereign state, Nietzsche was born a citizen ofPrussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, which was mostly part of the German Confederation

The German Confederation ( ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved ...

. His birthplace, Röcken, is in the modern German state of Saxony-Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt ( ; ) is a States of Germany, state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.17 million inhabitants, making it the List of German states ...

. When he accepted his post at Basel, Nietzsche applied for annulment of his Prussian citizenship. The official revocation of his citizenship came in a document dated 17 April 1869, and for the rest of his life he remained officially stateless.

At least towards the end of his life, Nietzsche believed his ancestors were Polish. He wore a signet ring

A seal is a device for making an impression in Sealing wax, wax, clay, paper, or some other medium, including an Paper embossing, embossment on paper, and is also the impression thus made. The original purpose was to authenticate a document, or ...

bearing the Radwan coat of arms, traceable back to Polish nobility

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

of medieval times and the surname "Nicki" of the Polish noble (szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

) family bearing that coat of arms. Gotard Nietzsche, a member of the Nicki family, left Poland for Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

. His descendants later settled in the Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony ( or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356 to 1806 initially centred on Wittenberg that came to include areas around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz. It was a ...

circa the year 1700. Nietzsche wrote in 1888, "My ancestors were Polish noblemen (Nietzky); the type seems to have been well preserved despite three generations of German mothers." At one point, Nietzsche became even more adamant about his Polish identity. "I am a pure-blooded Polish nobleman, without a single drop of bad blood, certainly not German blood." On yet another occasion, Nietzsche stated, "Germany is a great nation only because its people have so much Polish blood in their veins.... I am proud of my Polish descent." Nietzsche believed his name might have been Germanised, in one letter claiming, "I was taught to ascribe the origin of my blood and name to Polish noblemen who were called Niëtzky and left their home and nobleness about a hundred years ago, finally yielding to unbearable suppression: they were Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

."

Most scholars dispute Nietzsche's account of his family's origins. Hans von Müller debunked the genealogy put forward by Nietzsche's sister in favour of Polish noble heritage. Max Oehler, Nietzsche's cousin and curator of the Nietzsche Archive at Weimar