The history of the Jews in France deals with

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and Jewish communities in

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

since at least the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

. France was a centre of Jewish learning in the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, but

persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

increased over time, including multiple expulsions and returns. During the

French Revolution in the late 18th century, on the other hand, France was the first European country to

emancipate

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchi ...

its Jewish population.

Antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

still occurred in cycles and reached a high in the 1890s, as shown during the

Dreyfus affair, and in the 1940s, under

Nazi occupation

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at ...

and the

Vichy regime

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against ...

.

Before 1919, most French Jews lived in

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, with many being very proud to be fully assimilated into French culture, and they comprised an upscale subgroup. A more traditional Judaism was based in

Alsace-Lorraine, which was recovered by The German Empire in 1871 and taken by France in 1918 following World War I. In addition, numerous Jewish refugees and immigrants came from Russia and eastern and central Europe in the early 20th century, changing the character of French Judaism in the 1920s and 1930s. These new arrivals were much less interested in assimilation into French culture. Some supported such new causes as

Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

, the

Popular Front and communism, the latter two being popular among the

French political left.

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Vichy government

collaborated

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. The f ...

with

Nazi occupiers to deport a large number of both French Jews and foreign Jewish refugees to

concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

.

[ By the war's end, 25% of the Jewish population of France had been murdered in the ]Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

, though this was a lower proportion than in most other countries under Nazi occupation

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at ...

.Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem (; ) is Israel's official memorial institution to the victims of Holocaust, the Holocaust known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (). It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; echoing the stories of the ...

br>

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

). The Jewish community in France is estimated to number 480,000–550,000, depending in part on the definition being used. French Jewish communities are concentrated in the metropolitan areas of Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, which has the largest Jewish population among all European cities (277,000), Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, with a population of 70,000, Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one million[Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...]

and Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

.

The majority of French Jews in the 21st century are Sephardi

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

and Mizrahi

''Mizrachi'' or ''Mizrahi'' () has two meanings.

In the literal Hebrew meaning ''eastern'', it may refer to:

* Mizrahi Jews, Jews from the Middle East and North Africa

* Mizrahi (surname), a Sephardic surname, given to Jews who got to the Iberia ...

North African Jews, many of whom (or their parents) emigrated from former French colonies of North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

after those countries gained independence in the 1950s and 1960s. They span a range of religious affiliations, from the ultra-Orthodox Haredi

Haredi Judaism (, ) is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that is characterized by its strict interpretation of religious sources and its accepted (Jewish law) and traditions, in opposition to more accommodating values and practices. Its members are ...

communities to the large segment of Jews who are entirely secular and who often marry outside the Jewish community.

Approximately 200,000 French Jews live in Israel. Since 2010 or so, more have been making aliyah

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine (region), Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the Israel ...

in response to rising antisemitism in France.

Roman and Merovingian periods

According to the ''Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on the ...

'' (1906), "The first settlements of Jews in Europe are obscure. From 163 BCE there is evidence of Jews in Rome .. In the year 6 C.E. there were Jews at Vienne Vienne may refer to:

Places

*Vienne (department), a department of France named after the river Vienne

*Vienne, Isère, a city in the French department of Isère

* Vienne-en-Arthies, a village in the French department of Val-d'Oise

* Vienne-en-Bessi ...

and Gallia Celtica

Gallia Celtica, meaning "Celtic Gaul" in Latin, was a cultural region of Gaul inhabited by Celts, located in what is now France, Switzerland, Luxembourg and the west bank of the Rhine River in Germany.

According to Roman ethnography and Julius C ...

; in the year 39 at Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Colonia (Roman), Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon, France, Lyon.

The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but cont ...

(i.e. Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

)".Hilary of Poitiers

Hilary of Poitiers (; ) was Bishop of Poitiers and a Doctor of the Church. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hammer of the Arians" () and the " Athanasius of the West". His name comes from the Latin word for happy or cheerful. In addition t ...

(died 366) for having fled from the Jewish society. The emperors Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( ; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450), called "the Calligraphy, Calligrapher", was Roman emperor from 402 to 450. He was proclaimed ''Augustus (title), Augustus'' as an infant and ruled as the Eastern Empire's sole emperor after the ...

and Valentinian III

Valentinian III (; 2 July 41916 March 455) was Roman emperor in the Western Roman Empire, West from 425 to 455. Starting in childhood, his reign over the Roman Empire was one of the longest, but was dominated by civil wars among powerful general ...

sent a decree to Amatius, prefect of Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

(9 July 425), that prohibited Jews and pagans from practising law or holding public offices (''militandi''). This was to prevent Christians from being subject to them and possibly incited to change their faith. At the funeral of Hilary, Bishop of Arles

Hilary of Arles, also known by his Latin name Hilarius (c. 403–449), was a bishop of Arles in Southern France. He is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church, with 5 May being his feast day.

Life

In his ea ...

, in 449, Jews and Christians mingled in crowds and wept; the former were said to have sung psalms in Hebrew.Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, Arles

Arles ( , , ; ; Classical ) is a coastal city and Communes of France, commune in the South of France, a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône Departments of France, department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Reg ...

, Uzès

Uzès (; ) is a commune in the Gard department in the Occitanie region of Southern France. Uzès lies about north-northeast of Nîmes, west of Avignon, and southeast of Alès.

History

Originally ''Ucetia'' or ''Eutica'' in Latin, Uzès wa ...

, Narbonne

Narbonne ( , , ; ; ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and was ...

, Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand (, , ; or simply ; ) is a city and Communes of France, commune of France, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes regions of France, region, with a population of 147,284 (2020). Its metropolitan area () had 504,157 inhabitants at the 2018 ...

, Orléans

Orléans (,["Orleans"](_blank)

(US) and [Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...]

, and Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

. These cities had generally been centers of ancient Roman administration and were located on the great commercial routes. The Jews built synagogues

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

in these cities. In harmony with the Theodosian code

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' ("Theodosian Code") is a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 429 an ...

, and according to an edict of 331 by the emperor Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine g ...

, the Jews were organized for religious purposes as they were in the Roman empire. They appear to have had priests (rabbis

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as '' semikha''—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

or ḥazzanim

A ''hazzan'' (; , lit. Hazan) or ''chazzan'' (, plural ; ; ) is a Jewish musician or precentor trained in the vocal arts who leads the congregation in songful prayer. In English, this prayer leader is often referred to as a cantor, a term also ...

), archisynagogues, patersynagogues, and other synagogue officials. The Jews worked principally as merchants, as they were prohibited from owning land; they also served as tax collectors, sailors, and physicians. They probably remained under Roman law until the triumph of Christianity, with the status established by

They probably remained under Roman law until the triumph of Christianity, with the status established by Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname Caracalla (; ), was Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father and then r ...

, on a footing of equality with their fellow citizens. Their association with fellow citizens was generally amicable, even after the establishment of Christianity in Gaul. The Christian clergy participated in some Jewish feasts; intermarriage between Jews and Christians sometimes occurred; and the Jews made proselytes. Worried about Christians adopting Jewish religious customs, the third Council of Orléans

The third council of national stature, or third Council of Orléans, was a synod of the Catholic bishops of France. It opened around 7 May 538 and was presided over by Loup, Archbishop of Lyon. It established mainly:

* Sunday as day of the Lord;

* ...

(539) warned the faithful against Jewish "superstitions", and ordered them to abstain from traveling on Sunday and from adorning their persons or dwellings on that day. In the 6th century, a Jewish community thrived in Paris.Pepin the Short

the Short (; ; ; – 24 September 768), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian dynasty, Carolingian to become king.

Pepin was the son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel and his wife Rotrude of H ...

. The Jews on the other hand continued to dwell and to prosper in what is now Southern France

Southern France, also known as the south of France or colloquially in French as , is a geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', Atlas e ...

, then known as Septimania

Septimania is a historical region in modern-day southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of '' Gallia Narbonensis'' that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septimania was ceded to their king, Theod ...

and a dependency of the Visigothic

The Visigoths (; ) were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied barbarian military group united under the comman ...

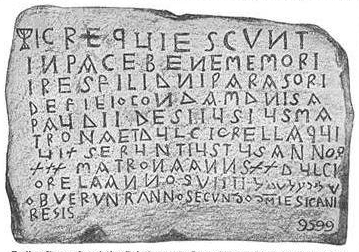

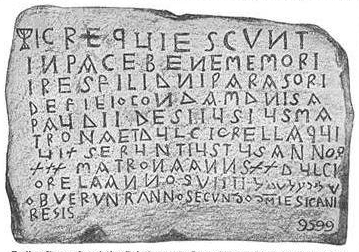

kings of Spain. From this epoch (689) dates the earliest known inscription relating to the Jews of France, the "Funerary Stele of Justus, Matrona and Dulciorella" of Narbonne, written in Latin and Hebrew.

Carolingian period

The presence of Jews in France under Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

is documented, with their position being regulated by law. Exchanges with the Orient strongly declined with the presence of Arabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

in the Mediterranean sea. Trading and importing of oriental products such as gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

, black pepper

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit (the peppercorn), which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in diameter ...

or papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

almost disappeared under the Carolingians

The Carolingian dynasty ( ; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid ...

. The Radhanite

The Radhanites or Radanites (; ) were early medieval Jewish merchants, active in the trade between Christendom and the Muslim world during roughly the 8th to the 10th centuries.

Many trade routes previously established under the Roman Empire cont ...

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

traders were nearly the only group to maintain trade between the Occident and the Orient.

Charlemagne fixed a formula for the Jewish oath to the state. He allowed Jews to enter into lawsuits with Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

. They were not allowed to require Christians to work on Sundays. Jews were not allowed to trade in currency

A currency is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins. A more general definition is that a currency is a ''system of money'' in common use within a specific envi ...

, wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink made from Fermentation in winemaking, fermented fruit. Yeast in winemaking, Yeast consumes the sugar in the fruit and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Wine is most often made f ...

, or grain. Legally, Jews belonged to the emperor and could be tried only by him. But the numerous provincial councils which met during Charlemagne's reign were not concerned with the Jewish communities.

Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (; ; ; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aquitaine from 781. As the only ...

(ruled 814–840), faithful to the principles of his father Charlemagne, granted strict protection to Jews, whom he respected as merchants. Like his father, Louis believed that 'the Jewish question' could be solved with the gradual conversion of Jews; according to medievalist scholar J. M. Wallace-Hadrill

John Michael Wallace-Hadrill (29 September 1916 – 3 November 1985) was a British academic and one of the foremost historians of the early Merovingian period. He held the Chichele Chair in Modern History at the University of Oxford between 1 ...

, some people believed this tolerance threatened the Christian unity of the Empire, which led to the strengthening of the Bishops at the expense of the Emperor. Saint Agobard of Lyon (779–841) had many run-ins with the Jews of France. He wrote about how rich and powerful they were becoming. Scholars such as Jeremy CohenLouis the Pious

Louis the Pious (; ; ; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aquitaine from 781. As the only ...

in the early 830s.Lothar

Lothar or Lothair is a Danish, Finnish, German, Norwegian, and Swedish masculine given name, while Lotár is a Hungarian masculine given name. Both names are modern forms of the Germanic Chlothar (which is a blended form of ''Hlūdaz'', me ...

and Agobard's entreaties to Pope Gregory IV

Pope Gregory IV (; died 25 January 844) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from October 827 to his death on 25 January 844. His pontificate was notable for the papacy’s attempts to intervene in the quarrels between Emperor L ...

gained them papal support for the overthrow of Emperor Louis. Upon Louis the Pious' return to power in 834, he deposed Saint Agobard from his see, to the consternation of Rome. There were unsubstantiated rumors in this period that Louis

Louis may refer to:

People

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

Other uses

* Louis (coin), a French coin

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

...

' second wife Judith

The Book of Judith is a deuterocanonical book included in the Septuagint and the Catholic Church, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Christian Old Testament of the Bible but Development of the Hebrew Bible canon, excluded from the ...

was a converted Jew, as she would not accept the ''ordinatio'' for their first child.

Jews were engaged in export trade, particularly traveling to Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

under Charlemagne. When the Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

disembarked on the coast of Narbonnese Gaul, they were taken for Jewish merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in goods produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Merchants have been known for as long as humans have engaged in trade and commerce. Merchants and merchant networks operated i ...

s. One authority said the Jewish traders boasted about buying whatever they pleased from bishops and abbots. Isaac the Jew, who was sent by Charlemagne in 797 with two ambassadors to Harun al-Rashid

Abū Jaʿfar Hārūn ibn Muḥammad ar-Rāshīd (), or simply Hārūn ibn al-Mahdī (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Hārūn al-Rāshīd (), was the fifth Abbasid caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate, reigning from September 786 unti ...

, the fifth Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 C ...

Caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

, was probably one of these merchants. He was said to have asked the Baghdad caliph for a rabbi to instruct the Jews whom he had allowed to settle at Narbonne

Narbonne ( , , ; ; ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and was ...

(see History of the Jews in Babylonia).

Capetians

Persecutions (987–1137)

There were widespread persecutions of Jews in France beginning in 1007 or 1009.

There were widespread persecutions of Jews in France beginning in 1007 or 1009.[ which also states that the King of France conspired with his vassals to destroy all the Jews on their lands who would not accept baptism, and many were put to death or killed themselves. Robert is credited with advocating forced conversions of local Jewry, as well as mob violence against Jews who refused. Among the dead was the learned Rabbi Senior. Robert the Pious is well known for his lack of religious tolerance and for the hatred which he bore toward heretics; it was Robert who reinstated the Roman imperial custom of burning heretics at the stake.]Richard II, Duke of Normandy

Richard II (died 28 August 1026), called the Good (French: ''Le Bon''), was the duke of Normandy from 996 until 1026.

Life

Richard was the eldest surviving son and heir of Richard the Fearless and Gunnor. He succeeded his father as the ruler o ...

, Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

Jewry suffered from persecutions that were so terrible that many women, in order to escape the fury of the mob, jumped into the river and drowned. A notable of the town, Jacob b. Jekuthiel, a Talmudic scholar, sought to intercede with Pope John XVIII

Pope John XVIII (; died June or July 1009) was the bishop of Rome and nominal ruler of the Papal States from January 1004 (25 December 1003 NS) to his abdication in July 1009. He wielded little temporal power, ruling during the struggle betwee ...

to stop the persecution in Lorraine (1007). Jacob undertook the journey to Rome, but was imprisoned with his wife and four sons by Duke Richard, and escaped death only by allegedly miraculous means. He left his eldest son, Judah, as a hostage with Richard while he and his wife and three remaining sons went to Rome. He bribed the pope with seven gold marks and two hundred pounds, who thereupon sent a special envoy to King Robert ordering him to stop the persecutions.Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century History of Germany, German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to ...

. According to Adémar, Christians urged by Pope Sergius IV

Pope Sergius IV (died 12 May 1012) was the bishop of Rome and nominal ruler of the Papal States from 31 July 1009 to his death. His temporal power (papal), temporal power was eclipsed by the patrician John Crescentius. Sergius IV may have calle ...

were shocked by the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also known as the Church of the Resurrection, is a fourth-century church in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. The church is the seat of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Some ...

in Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

by the Muslims in 1009. After the destruction, European reaction to the rumor of the letter was of shock and dismay, Cluniac

Cluny Abbey (; , formerly also ''Cluni'' or ''Clugny''; ) is a former Order of Saint Benedict, Benedictine monastery in Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France. It was dedicated to Saint Peter, Saints Peter and Saint Paul, Paul.

The abbey was constructed ...

monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

Rodulfus Glaber

Rodulfus (or Radulfus or Raoul Glaber; 985–1047), was an 11th-century Benedictine chronicler.

Life

Glaber was born in 985 in Burgundy. At the behest of his uncle, a monk at Saint-Léger-de-Champeaux (now Saint-Léger-Triey, Glaber was sent to ...

blamed the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

for the destruction. In that year Alduin, Bishop of Limoges

The Diocese of Limoges (Latin: ''Dioecesis Lemovicensis''; French: ''Diocèse de Limoges'') is a Latin Church diocese of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese comprises the '' départments'' of Haute-Vienne and Creuse. After the Concordat ...

(bishop 990–1012), offered the Jews of his diocese the choice between baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

and exile. For a month theologians held disputations with the Jews, but without much success, for only three or four of Jews abjured their faith; others killed themselves; and the rest either fled or were expelled from Limoges

Limoges ( , , ; , locally ) is a city and Communes of France, commune, and the prefecture of the Haute-Vienne Departments of France, department in west-central France. It was the administrative capital of the former Limousin region. Situated o ...

.[ By 1030, Rodulfus Glaber knew more concerning this story. According to his 1030 explanation, Jews of ]Orléans

Orléans (,["Orleans"](_blank)

(US) and [Pope Alexander II

Pope Alexander II (1010/1015 – 21 April 1073), born Anselm of Baggio, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1061 to his death in 1073. Born in Milan, Anselm was deeply involved in the Pataria reform mo ...]

wrote to Béranger, Viscount of Narbonne The viscount of Narbonne was the secular ruler of Narbonne in the Middle Ages. Narbonne had been the capital of the Visigoth province of Septimania, until the 8th century, after which it became the Carolingian Viscounty of Narbonne. Narbonne was nom ...

and to Guifred, bishop of the city, praising them for having prevented the massacre of the Jews in their district, and reminding them that God does not approve of the shedding of blood. In 1065 also, Alexander admonished Landulf VI of Benevento

Landulf VI (died 27 November 1077) was the last Lombard prince of Benevento. Unlike his predecessors, he never had a chance to rule alone and independently. The principality lost its independence in 1051, at which point Landulf was only co-ruling ...

"that the conversion of Jews is not to be obtained by force." Also in the same year, Alexander called for a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

against the Moors in Spain.

Franco-Jewish literature

During this period, which continued until the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

, Jewish culture flourished in the South and North of France. The initial interest included poetry, which was at times purely liturgical, but which more often was a simple scholastic exercise without aspiration, destined rather to amuse and instruct than to move. Following this came Biblical exegesis, the simple interpretation of the text, with neither daring nor depth, reflecting a complete faith in traditional interpretation, and based by preference on the ''Midrashim'', despite their fantastic character. Finally, and above all, their attention was occupied with the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

and its commentaries. The text of this work, together with that of the writings of the ''Geonim

''Geonim'' (; ; also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated Gaonim, singular Gaon) were the presidents of the two great Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Babylonian Talmudic Academies of Sura Academy , Sura and Pumbedita Academy , Pumbedita, in t ...

'', particularly their ''responsa

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars i ...

'', was first revised and copied; then these writings were treated as a ''corpus juris

The legal term ''Corpus Juris'' means "body of law".

It was originally used by the Ancient Rome, Romans for several of their collections of all the laws in a certain field—see ''Corpus Juris Civilis''—and was later adopted by medieval jurists ...

'', and were commented upon and studied both as a pious exercise in dialectics and from the practical point of view. While most of the focus of Jewish authors was religious, they did discuss other subjects, like the papal presence in their communities.

Rashi

The great Jewish figure who dominated the second half of the 11th century, as well as the whole rabbinical history of France, was

The great Jewish figure who dominated the second half of the 11th century, as well as the whole rabbinical history of France, was Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki (; ; ; 13 July 1105) was a French rabbi who authored comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible. He is commonly known by the List of rabbis known by acronyms, Rabbinic acronym Rashi ().

Born in Troyes, Rashi stud ...

(Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki) of Troyes

Troyes () is a Communes of France, commune and the capital of the Departments of France, department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within ...

(1040–1105). He personified the genius of northern French Judaism: its devoted attachment to tradition; its untroubled faith; its piety, ardent but free from mysticism. His works are distinguished by their clarity, directness, and are written in a simple, concise, unaffected style, suited to his subject.Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

, which was the product of colossal labor, and which eclipsed the similar works of all his predecessors, by its clarity and soundness made the study of that vast compilation easy, and soon became its indispensable complement. Every edition of the Talmud that was ever published has this commentary printed on the same page of the Talmud itself. His commentary on the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

(particularly on the Pentateuch), a sort of repertory of the ''Midrash

''Midrash'' (;["midrash"]

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

'', served for edification, but also advanced the taste for seeking the plain and true meaning of the bible. The school which he founded at Troyes

Troyes () is a Communes of France, commune and the capital of the Departments of France, department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within ...

, his birthplace, after having followed the teachings of those of Worms

The World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) is a taxonomic database that aims to provide an authoritative and comprehensive catalogue and list of names of marine organisms.

Content

The content of the registry is edited and maintained by scien ...

and Mainz

Mainz (; #Names and etymology, see below) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, and with around 223,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 35th-largest city. It lies in ...

, immediately became famous. Around his chair were gathered Simḥah b. Samuel, R. Shamuel b. Meïr

Samuel ben Meir (Troyes, c. 1085 – c. 1158), after his death known as the "Rashbam", a Hebrew acronym for RAbbi SHmuel Ben Meir, was a leading French Tosafist and grandson of Shlomo Yitzhaki, "Rashi".

Biography

He was born in the vicinity of T ...

(Rashbam), and Shemaya, his grandsons; likewise Shemaria, Judah b. Nathan, and Isaac Levi b. Asher, all of whom continued his work. The school's Talmudic commentaries and interpretations are the basis and starting point for the Ashkenazic tradition of how to interpret and understand the Talmud's explanation of Biblical laws. In many cases, these interpretations differ substantially from those of the Sephardim, which results in differences between how Ashkenazim and Sephardim hold what constitutes the practical application of the law. In his Biblical commentaries, he availed himself of the works of his contemporaries. Among them must be cited Moses ha-Darshan

Moshe haDarshan (circa early 11th century) (, trans. "Moses the preacher") was chief of the yeshiva of Narbonne, and perhaps the founder of Jewish exegetical studies in France. Along with Rashi, his writings are often cited as the first extant w ...

, chief of the school of Narbonne, who was perhaps the founder of exegetical studies in France, and Menachem b. Ḥelbo. Thus the 11th century was a period of fruitful activity in literature. Thenceforth French Judaism became one of the poles within Judaism.

The Crusades

The Jews of France suffered during the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

(1096), when the crusaders are stated, for example, to have shut up the Jews of Rouen in a church and to have murdered them without distinction of age or sex, sparing only those who accepted baptism.Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

document, the Jews throughout France were at that time in great fear and wrote to their brothers in the Rhine countries making known to them their terror and asking them to fast and pray.

Expulsions and Returns

Expulsion from France, 1182

The

The First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

led to nearly a century of accusations (blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mu ...

) against the Jews, many of whom were burned or attacked in France. Immediately after the coronation of Philip Augustus

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), also known as Philip Augustus (), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks (Latin: ''rex Francorum''), but from 1190 onward, Philip became the firs ...

on 14 March 1181, the King ordered the Jews arrested on a Saturday, in all their synagogues, and despoiled of their money and their investments. In the following April 1182, he published an edict of expulsion, but according to the Jews a delay of three months for the sale of their personal property. Immovable property, however, such as houses, fields, vines, barns, and wine presses, he confiscated. The Jews attempted to win over the nobles to their side but in vain. In July they were compelled to leave the royal domains of France (and not the whole kingdom); their synagogues were converted into churches. These successive measures were simply expedients to fill the royal coffers. The goods confiscated by the king were at once converted into cash.

During the century which terminated so disastrously for the Jews, their condition was not altogether bad, especially if compared with that of their brethren in Germany. Thus may be explained the remarkable intellectual activity which existed among them, the attraction that it exercised over the Jews of other countries, and the numerous works produced in those days. The impulse given by Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki (; ; ; 13 July 1105) was a French rabbi who authored comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible. He is commonly known by the List of rabbis known by acronyms, Rabbinic acronym Rashi ().

Born in Troyes, Rashi stud ...

to study did not cease with his death; his successors—the members of his family first among them—continued his work. Research moved within the same limits as in the preceding century, and dealt mainly with the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

, rabbinical jurisprudence, and Biblical exegesis.

Recalled by Philip Augustus, 1198

This century, which opened with the return of the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

to France proper (then almost reduced to the Île de France

Ile or ILE may refer to:

Ile

* Ile, a Puerto Rican singer

* Ile District (disambiguation), multiple places

* Ilé-Ifẹ̀, an ancient Yoruba city in south-western Nigeria

* Interlingue (ISO 639:ile), a planned language

* Isoleucine, an amino aci ...

), closed with their complete exile from the country in a larger sense. In July 1198, Philip Augustus, "contrary to the general expectation and despite his own edict, recalled the Jews to Paris and made the churches of God suffer great persecutions" (Rigord). The king adopted this measure from no good will toward the Jews, for he had shown his true sentiments a short time before in the Bray affair. But since then he had learned that the Jews could be an excellent source of income from a fiscal point of view, especially as money-lenders. Not only did he recall them to his estates, but he gave state sanction by his ordinances to their operations in banking and pawnbroking. He placed their business under control, determined the legal rate of interest, and obliged them to have seals affixed to all their deeds. Naturally, this trade was taxed, and the affixing of the royal seal was paid for by the Jews. Henceforward there was in the treasury a special account called "Produit des Juifs", and the receipts from this source increased continually. At the same time, it was in the interest of the treasury to secure possession of the Jews, considered a fiscal resource. The Jews were therefore made serfs of the king in the royal domain, just at a time when the charters, becoming wider and wider, tended to bring about the disappearance of serfdom. In certain respects their position became even harder than that of serfs, for the latter could in certain cases appeal to custom and were often protected by the Church; but there was no custom to which the Jews might appeal, and the Church laid them under its ban. The kings and the lords said "my Jews" just as they said "my lands", and they disposed in like manner of the one and of the other. The lords imitated the king: "they endeavored to have the Jews considered an inalienable dependence of their fiefs, and to establish the usage that if a Jew domiciled in one barony passed into another, the lord of his former domicil should have the right to seize his possessions." This agreement was made in 1198 between the king and the Count of Champagne in a treaty, the terms of which provided that neither should retain in his domains the Jews of the other without the latter's consent and furthermore that the Jews should not make loans or receive pledges without the express permission of the king and the count. Other lords made similar conventions with the king. Thenceforth they too had a revenue known as the ''Produit des Juifs'', comprising the taille

The ''taille'' () was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in ''Ancien Régime'' France. The tax was imposed on each household and was based on how much land it held, and was paid directly to the state.

History

Originally ...

, or annual quit-rent, the legal fees for the writs necessitated by the Jews' law trials, and the seal duty. A thoroughly characteristic feature of this fiscal policy is that the bishops (according to the agreement of 1204 regulating the spheres of ecclesiastical and seigniorial jurisdiction) continued to prohibit the clergy from excommunicating those who sold goods to the Jews or who bought from them.

The practice of "retention treaties" spread throughout France after 1198. Lords intending to impose a heavy tax (''captio'', literally "capture") on Jews living in their lordship (''dominium'') signed treaties with their neighbours, whereby the latter refused to permit the former's Jews entry into his domains, thus "retaining" them for the lord to tax. This practice arose in response to the common flight of Jews in the face of a ''captio'' to a different ''dominium'', where they purchased the right to settle unmolested by gifts (bribes) to their new lord. In May 1210 the crown negotiated a series of treaties with the neighbours of the royal demesne and successfully "captured" its Jews with a large tax levy. From 1223 on, however, the Count Palatine of Champagne refused to sign any such treaties, and in that year, he even refused to affirm the crown's asserted right to force non-retention policies on its barons. Such treaties became obsolete after Louis IX's ordinance of Melun (1230), when it became illegal for a Jew to migrate between lordships. This ordinance—the first piece of public legislation in France since Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty ( ; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid c ...

times—also declared it treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

to refuse non-retention.

Under Louis VIII

Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII (5 September 1187 8 November 1226), nicknamed The Lion (), was King of France from 1223 to 1226. As a prince, he invaded Kingdom of England, England on 21 May 1216 and was Excommunication in the Catholic Church, excommunicated by a ...

(1223–26), in his ''Etablissement sur les Juifs'' of 1223, while more inspired with the doctrines of the Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a place/building for Christian religious activities and praying

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian comm ...

than his father, Philip Augustus, knew also how to look after the interests of his treasury. Although he declared that from 8 November 1223, the interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a debtor or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distinct f ...

on Jews' debts should no longer hold good, he at the same time ordered that the capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

should be repaid to the Jews in three years and that the debts due the Jews should be inscribed and placed under the control of their lords. The lords then collected the debts for the Jews, doubtless receiving a commission. Louis furthermore ordered that the special seal for Jewish deeds should be abolished and replaced by the ordinary one.

Twenty-six barons accepted Louis VIII's new measures, but Theobald IV (1201–53), the powerful Count of Champagne

The count of Champagne was the ruler of the County of Champagne from 950 to 1316. Champagne evolved from the County of Troyes in the late eleventh century and Hugh I was the first to officially use the title count of Champagne.

Count Theobal ...

, did not, since he had an agreement with the Jews that guaranteed their safety in return for extra income through taxation. Champagne's capital at Troyes was where Rashi had lived a century before, and Champagne continued to have a prosperous Jewish population. Theobald IV would become a major opposition force to Capetian dominance, and his hostility was manifest during the reign of Louis VIII. For example, during the siege of Avignon, he performed only the minimum service of 40 days and left for home amid charges of treachery.

Under Louis IX

In spite of all these restrictions designed to restrain, if not to suppress moneylending

In finance, a loan is the tender of money by one party to another with an agreement to pay it back. The recipient, or borrower, incurs a debt and is usually required to pay interest for the use of the money.

The document evidencing the debt ( ...

, Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis VI ...

(1226–70) (also known as Saint Louis), with his ardent piety and his submission to the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, unreservedly condemned loans at interest. He was less amenable than Philip Augustus to fiscal considerations. Despite former conventions, in an assembly held at Melun in December 1230, he compelled several lords to sign an agreement not to authorize Jews to make any loan. No one in the whole Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

was allowed to detain a Jew belonging to another, and each lord might recover a Jew who belonged to him, just as he might his own serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

(''tanquam proprium servum''), wherever he might find him and however long a period had elapsed since the Jew had settled elsewhere. At the same time, the ordinance of 1223 was enacted afresh, which only proves that it had not been carried into effect. Both king and lords were forbidden to borrow from Jews.

In 1234, Louis freed his subjects from a third of their registered debts to Jews (including those who had already paid their debts), but debtors had to pay the remaining two-thirds within a specified time. It was also forbidden to imprison Christians or to sell their real estate to recover debts owed to Jews. The king wished in this way to strike a deadly blow at usury.

In 1243, Louis ordered, at the urging of Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the Pa ...

, the burning in Paris of some 12,000 manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

copies of the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

and other Jewish works.

In order to finance his first Crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

, Louis ordered the expulsion of all Jews engaged in usury

Usury () is the practice of making loans that are seen as unfairly enriching the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in e ...

and the confiscation of their property, for use in his crusade, but the order for the expulsion was only partly enforced if at all. Louis left for the Seventh Crusade

The Seventh Crusade (1248–1254) was the first of the two Crusades led by Louis IX of France. Also known as the Crusade of Louis IX to the Holy Land, it aimed to reclaim the Holy Land by attacking Egypt, the main seat of Muslim power in the Nea ...

in 1248.

However, he did not cancel the debts owed by Christians. Later, Louis became conscience-stricken, and, overcome by scruples, he feared lest the treasury, by retaining some part of the interest paid by the borrowers, might be enriched with the product of usury. As a result, one-third of the debts was forgiven, but the other two-thirds were to be remitted to the royal treasury.

In 1251, while Louis was in captivity on the Crusade, a popular movement rose up with the intention of traveling to the east to rescue him; although they never made it out of northern France, Jews were subject to their attacks as they wandered throughout the country (see Shepherds' Crusade).

In 1257 or 1258 ("Ordonnances", i. 85), wishing, as he says, to provide for his safety of soul and peace of conscience, Louis issued a mandate for the restitution in his name of the amount of usurious interest which had been collected on the confiscated property, the restitution to be made either to those who had paid it or to their heirs.

Later, after having discussed the subject with his son-in-law, King Theobald II of Navarre

Theobald II (6/7 December 1239 – 4/5 December 1270) was King of Navarre and also, as Theobald V, Count of Champagne and Brie (region), Brie, from 1253 until his death. He was the son and successor of Theobald I of Navarre, Theobald I and the s ...

and Count of Champagne

The count of Champagne was the ruler of the County of Champagne from 950 to 1316. Champagne evolved from the County of Troyes in the late eleventh century and Hugh I was the first to officially use the title count of Champagne.

Count Theobal ...

, Louis decided on 13 September 1268 to arrest Jews and seize their property. But an order which followed close upon this last (1269) shows that on this occasion also Louis reconsidered the matter. Nevertheless, at the request of Paul Christian (Pablo Christiani), he compelled the Jews, under penalty of a fine, to wear at all times the ''rouelle'' or badge decreed by the Fourth Council of the Lateran

The Fourth Council of the Lateran or Lateran IV was convoked by Pope Innocent III in April 1213 and opened at the Lateran Palace in Rome on 11 November 1215. Due to the great length of time between the council's convocation and its meeting, m ...

in 1215. This consisted of a piece of red felt or cloth cut in the form of a wheel, four fingers in circumference, which had to be attached to the outer garment at the chest and back.

The Medieval Inquisition

The

The Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

, which had been instituted in order to suppress Catharism

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a he ...

, finally occupied itself with the Jews of Southern France who converted to Christianity. The popes complained that not only were baptized Jews returning to their former faith but that Christians also were being converted to Judaism. In March 1273, Pope Gregory X

Pope Gregory X (; – 10 January 1276), born Teobaldo Visconti, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 September 1271 to his death and was a member of the Third Order of St. Francis. He was elected at the ...

formulated the following rules: relapsed Jews, as well as Christians who abjured their faith in favor of "the Jewish superstition", were to be treated by the Inquisitors as heretics. The instigators of such apostasies, as those who received or defended the guilty ones, were to be punished in the same way as the delinquents.

In accordance with these rules, the Jews of Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

, who had buried a Christian convert in their cemetery, were brought before the Inquisition in 1278 for trial, with their rabbi, Isaac Males, being condemned to the stake. Philip IV at first ordered his seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

s not to imprison any Jews at the instance of the Inquisitors, but in 1299 he rescinded this order.

The Great Exile of 1306

Toward the middle of 1306 the treasury was nearly empty, and the king, as he was about to do the following year in the case of the Templars

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a military order of the Catholic faith, and one of the most important military orders in Western Christianity. They were founded in 11 ...

, condemned the Jews to banishment, and took forcible possession of their property, real and personal. Their houses, lands, and movable goods were sold at auction; and for the king were reserved any treasures found buried in the dwellings that had belonged to the Jews. That Philip the Fair

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip I from ...

intended merely to fill the gap in his treasury, and was not at all concerned about the well-being of his subjects, is shown by the fact that he put himself in the place of the Jewish moneylenders and exacted from their Christian debtors the payment of their debts, which they themselves had to declare. Furthermore, three months before the sale of the property of the Jews the king took measures to ensure that this event should be coincident with the prohibition of clipped money, in order that those who purchased the goods should have to pay in undebased coin. Finally, fearing that the Jews might have hidden some of their treasures, he declared that one-fifth of any amount found should be paid to the discoverer. It was on 22 July, the day after ''Tisha B'Av

Tisha B'Av ( ; , ) is an annual fast day in Judaism. A commemoration of a number of disasters in Jewish history, primarily the destruction of both Solomon's Temple by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Second Temple by the Roman Empire in Jerusal ...

'', a Jewish fast day, that the Jews were arrested. In prison they received notice that they had been sentenced to exile; that, abandoning their goods and debts, and taking only the clothes which they had on their backs and the sum of 12 ''sous tournois'' each, they would have to quit the kingdom within one month. Speaking of this exile, a French historian has said,In striking at the Jews, Philip the Fair at the same time dried up one of the most fruitful sources of the financial, commercial, and industrial prosperity of his kingdom.

To a large extent, the history of the Jews of France ceased. The span of control of the King of France had increased considerably in extent. Outside the Île de France

Ile or ILE may refer to:

Ile

* Ile, a Puerto Rican singer

* Ile District (disambiguation), multiple places

* Ilé-Ifẹ̀, an ancient Yoruba city in south-western Nigeria

* Interlingue (ISO 639:ile), a planned language

* Isoleucine, an amino aci ...

, it now comprised Champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

, the Vermandois

Vermandois was a French county that appeared in the Merovingian period. Its name derives from that of an ancient tribe, the Viromandui. In the 10th century, it was organised around two castellan domains: St Quentin (Aisne) and Péronne ( Som ...

, Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

, Perche

Perche () (French: ''le Perche'') is a former Provinces of France, province of France, known historically for its forests and, for the past two centuries, for the Percheron draft horse, draft horse breed. Until the French Revolution, Perche was ...

, Maine, Anjou

Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

** Du ...

, Touraine

Touraine (; ) is one of the traditional provinces of France. Its capital was Tours. During the political reorganization of French territory in 1790, Touraine was divided between the departments of Indre-et-Loire, :Loir-et-Cher, Indre and Vien ...

, Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

, the Marche, Lyonnais

The Lyonnais (, ) is a historical province of France which owes its name to the city of Lyon.

The geographical area known as the ''Lyonnais'' became part of the Kingdom of Burgundy after the division of the Carolingian Empire. The disintegra ...

, Auvergne

Auvergne (; ; or ) is a cultural region in central France.

As of 2016 Auvergne is no longer an administrative division of France. It is generally regarded as conterminous with the land area of the historical Province of Auvergne, which was dis ...

, and Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

, reaching from the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Ròse''; Franco-Provençal, Arpitan: ''Rôno'') is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and Southeastern France before dischargi ...

to the Pyrénées

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto.

F ...

. The exiles could not take refuge anywhere except in Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

, the county of Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

, Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

, Dauphiné

The Dauphiné ( , , ; or ; or ), formerly known in English as Dauphiny, is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was ...

, Roussillon

Roussillon ( , , ; , ; ) was a historical province of France that largely corresponded to the County of Roussillon and French Cerdagne, part of the County of Cerdagne of the former Principality of Catalonia. It is part of the region of ' ...

, and a part of Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

—all regions located in Empire. It is not possible to estimate the number of fugitives; that given by Grätz, 100,000, has no foundation in fact.

Return of the Jews to France, 1315

Nine years had hardly passed since the expulsion of 1306 when Louis X of France

Louis X (4 October 1289 – 5 June 1316), known as the Quarrelsome (), was King of France from 1314 and King of Navarre (as Louis I) from 1305 until his death. He emancipated serfs who could buy their freedom and readmitted Jews into the king ...

(1314–16) recalled the Jews. In an edict dated 28 July 1315, he permitted them to return for a period of twelve years, authorizing them to establish themselves in the cities in which they had lived before their banishment. He issued this edict in answer to the demands of the people. Geoffrey of Paris, the popular poet of the time, says in fact that the Jews were gentle in comparison with the Christians who had taken their place, and who had flayed their debtors alive; if the Jews had remained, the country would have been happier; for there were no longer any moneylenders at all. The king probably had the interests of his treasury also in view. The profits of the former confiscations had gone into the treasury, and by recalling the Jews for only twelve years he would have an opportunity for ransoming them at the end of this period. It appears that they gave the sum of 122,500 ''livres

Livre may refer to:

Currency

* French livre, one of a number of obsolete units of currency of France

* Livre tournois, one particular obsolete unit of currency of France

* Livre parisis, another particular obsolete unit of currency of France

* F ...

'' for the privilege of returning. It is also probable, as Adolphe Vuitry

Adolphe Vuitry (, 31 March 1813 – 23 June 1885) was a French lawyer, economist and politician.

He became recognized as an expert on finance. He was governor of the Banque de France from 1863 to 1864, then Minister-President of the Conseil d'Etat ...

states, that a large number of the debts owing to the Jews had not been recovered, and that the holders of the notes had preserved them; the decree of return specified that two-thirds of the old debts recovered by the Jews should go into the treasury. The conditions under which they were allowed to settle in the land are set forth in a number of articles; some of the guaranties which were accorded the Jews had probably been demanded by them and been paid for.

They were to live by the work of their hands or to sell merchandise of good quality; they were to wear the circular badge, and not discuss religion with laymen. They were not to be molested, either with regard to the chattels they had carried away at the time of their banishment, or with regard to the loans which they had made since then, or in general with regard to anything which had happened in the past. Their synagogues and their cemeteries were to be restored to them on condition that they would refund their value; or, if these could not be restored, the king would give them the necessary sites at a reasonable price. The books of the Law that had not yet been returned to them were also to be restored, with the exception of the Talmud. After the period of twelve years granted to them, the king might not expel the Jews again without giving them a year's time in which to dispose of their property and carry away their goods. They were not to lend on usury

Usury () is the practice of making loans that are seen as unfairly enriching the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in e ...

, and no one was to be forced by the king or his officers to repay to them usurious loans.

If they engaged in pawnbroking, they were not to take more than two deniers in the pound a week; they were to lend only on pledges. Two men with the title "auditors of the Jews" were entrusted with the execution of this ordinance and were to take cognizance of all claims that might arise in connection with goods belonging to the Jews that had been sold before the expulsion for less than half of what was regarded as a fair price. The king finally declared that he took the Jews under his special protection and that he desired to have their persons and property protected from all violence, injury, and oppression.

Expulsion of 1394