First Red Scare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The first Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of

On January 21, 1919, 35,000 shipyard workers in

On January 21, 1919, 35,000 shipyard workers in

The Overman Committee was a special five-man subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary chaired by North Carolina Democrat Lee Slater Overman. First charged with investigating German subversion during World War I, its mandate was extended on February 4, 1919, just a day after the announcement of the Seattle General Strike, to study "any efforts being made to propagate in this country the principles of any party exercising or claiming to exercise any authority in Russia" and "any effort to incite the overthrow of the Government of this country". The Committee's hearings into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted from February 11 to March 10, 1919, developed an alarming image of

The Overman Committee was a special five-man subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary chaired by North Carolina Democrat Lee Slater Overman. First charged with investigating German subversion during World War I, its mandate was extended on February 4, 1919, just a day after the announcement of the Seattle General Strike, to study "any efforts being made to propagate in this country the principles of any party exercising or claiming to exercise any authority in Russia" and "any effort to incite the overthrow of the Government of this country". The Committee's hearings into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted from February 11 to March 10, 1919, developed an alarming image of

In late April 1919, approximately 36 booby trap bombs were mailed to prominent politicians, including the Attorney General of the United States, judges, businessmen (including

In late April 1919, approximately 36 booby trap bombs were mailed to prominent politicians, including the Attorney General of the United States, judges, businessmen (including

Though the leadership of the

Though the leadership of the

Despite two attempts on his life in April and June 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer moved slowly to find a way to attack the source of the violence. An initial raid in July 1919 against a small anarchist group in Buffalo failed when a federal judge tossed out his case. In August, he organized the General Intelligence Division within the Department of Justice and recruited

Despite two attempts on his life in April and June 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer moved slowly to find a way to attack the source of the violence. An initial raid in July 1919 against a small anarchist group in Buffalo failed when a federal judge tossed out his case. In August, he organized the General Intelligence Division within the Department of Justice and recruited

On December 21, 1919, the ''Buford'', a ship the press nicknamed the "Soviet Ark", left New York harbor with 249 deportees. Of those, 199 had been detained in the November

On December 21, 1919, the ''Buford'', a ship the press nicknamed the "Soviet Ark", left New York harbor with 249 deportees. Of those, 199 had been detained in the November

On January 7, 1920, at the first session of the

On January 7, 1920, at the first session of the

''To the American People: Report Upon the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice''

(Washington, DC: National Popular Government League, 1920). Co-authors include

''Bolshevik Propaganda: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary''

United States Senate, Sixty-fifth Congress, Third Session and Thereafter, Pursuant to S. Res. 439 and 469. February 11, 1919, to March 10, 1919 (Government Printing Office, 1919) * Waldman, Louis

''Albany: The Crisis in Government: The History of the Suspension, Trial and Expulsion from the New York State Legislature in 1920 of the Five Socialist Assemblymen by Their Political Opponents''

(New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920)

online

* Guariglia, Matthew. "Wrench in the Deportation Machine: Louis F. Post's Objection to Mechanized Red Scare Bureaucracy." ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' 38.1 (2018): 62–77.

Brown, R.G., et al., ''To the American People: Report Upon the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice''

(Washington, DC: National Popular Government League, 1920). Co-authors include

"Chicagoans Cheer Tar Who Shot Man: Sailor Wounds Pageant Spectator Disrespectful to Flag"

, ''The Washington Post'', May 7, 1919. Accessed May 2, 2007

, ''The Nation'', April 17, 1920. Retrieved April 13, 2005. * Nelles, Walter

''Seeing Red: Civil Liberty and the Law in the Period Following the War''

(NY: American Civil Liberties Union, 1920), accessed February 11, 2010.

A. Mitchell Palmer, ''America or Anarchy? An Appeal to Red-Blooded Americans to Strike an Effective Blow for the Protection of the Country We Love from the Red Menace Which Shows Its Ugly Head on Every Hand''

, published as a pamphlet by Martin L. Davey, Member of Congress from the 14th District of Ohio. Retrieved April 13, 2005.

, ''World War I At Home: Readings on American Life, 1914–1920'' (NY: John Wiley and Sons), 185–189. Retrieved April 13, 2005.

{{Authority control 1919 in the United States 1920 in the United States Anarchism in the United States Anti-anarchism in the United States Anti-communism in the United States Conspiracy theories involving communism History of the United States (1917–1945) Industrial Workers of the World Political and cultural purges Political repression in the United States Presidency of Woodrow Wilson Reactions to the Russian Revolution and Civil War Red Scare, *1 Revolutions of 1917–1923 Russia–United States relations Urban warfare

far-left

Far-left politics, also known as extreme left politics or left-wing extremism, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single, coherent definition; some ...

movements, including Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

and anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, due to real and imagined events; real events included the Russian 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, German Revolution of 1918–1919

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, and anarchist bombings in the U.S. At its height in 1919–1920, concerns over the effects of radical political agitation in American society and the alleged spread of socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, and anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

in the American labor movement fueled a general sense of concern.

The scare had its origins in the hyper-nationalism of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

as well as the Russian Revolution. At the war's end, following the October Revolution, American authorities saw the threat of communist revolution in the actions of organized labor

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

, including such disparate cases as the Seattle General Strike and the Boston Police Strike and then in the bombing campaign directed by anarchist groups at political and business leaders. Fueled by labor unrest and the anarchist bombings, and then spurred on by the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchist ...

and attempts by United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the Federal government of the United States, federal government. The attorney general acts as the princi ...

A. Mitchell Palmer to suppress radical organizations, it was characterized by exaggerated rhetoric, illegal searches and seizures, unwarranted arrests and detentions, and the deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people by a state from its sovereign territory. The actual definition changes depending on the place and context, and it also changes over time. A person who has been deported or is under sen ...

of several hundred suspected radicals and anarchists. In addition, the growing anti-immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

nativist movement among Americans viewed increasing immigration from Southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

as a threat to American political and social stability.

Bolshevism and the threat of a communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

-inspired revolution in the U.S. became the overriding explanation for challenges to the social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social orde ...

, even for such largely unrelated events as incidents of interracial violence during the Red Summer

The Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which Terrorism in the United States#White nationalism and white supremacy, white supremacist terrorism and Mass racial violence in the United States, racial riots occurred in more than three d ...

of 1919. Fear of radicalism was used to explain the suppression of freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

in the form of display of certain flags and banners. In April 1920, concerns peaked with J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

telling the nation to prepare for a bloody uprising on May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

. Police and militias prepared for the worst, but May Day passed without event. Soon, public opinion and the courts turned against Palmer, putting an end to his raids and the first Red Scare.

Origins

In reaction to subversive and militantleftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social hierarchies. Left-wing politi ...

actions in the United States, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

passed the Espionage Act in 1917, the Sedition Act of 1918, and the Immigration Act of 1918. The Espionage Act made it a crime to interfere with the operation or success of the military, and the Sedition Act forbade Americans to use "disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language" about the United States government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

, flag

A flag is a piece of textile, fabric (most often rectangular) with distinctive colours and design. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic design employed, and fla ...

, or armed forces of the United States during war. The Immigration Act of 1918 targeted anarchists by name and was used to deport Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

, Alexander Berkman and Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani (; 12 August 1861 – 4 November 1931) was an Italian insurrectionary anarchism, insurrectionary anarchist and Communism, communist best known for his advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", a strategy of political assassinations ...

, among others.

Progression of events

Seattle General Strike

On January 21, 1919, 35,000 shipyard workers in

On January 21, 1919, 35,000 shipyard workers in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

went on strike seeking wage increases. They appealed to the Seattle Central Labor Council for support from other unions and found widespread enthusiasm. Within two weeks, more than 100 local unions joined in a call on February 3 for a general strike to begin on the morning of February 6. The 60,000 total strikers paralyzed the city's normal activities, like streetcar service, schools, and ordinary commerce, while their General Strike Committee maintained order and provided essential services, like trash collection and milk deliveries.

Even before the strike began, the press tried to persuade the unions to reconsider. In part they were frightened by some of labor's rhetoric, like the labor newspaper editorial that proclaimed: "We are undertaking the most tremendous move ever made by labor in this country ... We are starting on a road that leads – NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!" Daily newspapers saw the general strike as a foreign import: "This is America – not Russia," one said when denouncing the general strike. The non-striking part of Seattle's population imagined the worst and stocked up on food. Hardware stores sold their stock of guns.

Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson announced that he had 1500 police and 1500 federal troops on hand to put down any disturbances. He personally oversaw their deployment throughout the city.Murray, 63 "The time has come", he said, "for the people in Seattle to show their Americanism ... The anarchists in this community shall not rule its affairs." He promised to use them to replace striking workers, but never carried out that threat.

Meanwhile, the national leadership of the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL) and international leaders of some of the Seattle locals recognized how inflammatory the general strike was proving in the eyes of the American public and Seattle's middle class. Press and political reaction made the general strike untenable, and they feared Seattle labor would lose gains made during the war if it continued. The national press called the general strike "Marxian" and "a revolutionary movement aimed at existing government". "It is only a middling step", said the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1847, it was formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper", a slogan from which its once integrated WGN (AM), WGN radio and ...

'', "from Petrograd to Seattle."

As early as February 8 some unions began to return to work at the urging of their leaders. Some workers went back to work as individuals, perhaps fearful of losing their jobs if the Mayor acted on his threats or in reaction to the pressure of life under the general strike. The executive committee of the General Strike Committee first recommended ending the general strike on February 8 but lost that vote. Finally on February 10, the General Strike Committee voted to end the strike the next day. The original strike in the shipyards continued.

Though the general strike collapsed because labor leadership viewed it as a misguided tactic from the start, Mayor Hanson took credit for ending the five-day strike and was hailed for it by the press. He resigned a few months later and toured the country giving lectures on the dangers of "domestic bolshevism". He earned $38,000 in seven months, five times his annual salary as mayor. He published a pamphlet called ''Americanism versus Bolshevism''.

Overman Committee

The Overman Committee was a special five-man subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary chaired by North Carolina Democrat Lee Slater Overman. First charged with investigating German subversion during World War I, its mandate was extended on February 4, 1919, just a day after the announcement of the Seattle General Strike, to study "any efforts being made to propagate in this country the principles of any party exercising or claiming to exercise any authority in Russia" and "any effort to incite the overthrow of the Government of this country". The Committee's hearings into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted from February 11 to March 10, 1919, developed an alarming image of

The Overman Committee was a special five-man subcommittee of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary chaired by North Carolina Democrat Lee Slater Overman. First charged with investigating German subversion during World War I, its mandate was extended on February 4, 1919, just a day after the announcement of the Seattle General Strike, to study "any efforts being made to propagate in this country the principles of any party exercising or claiming to exercise any authority in Russia" and "any effort to incite the overthrow of the Government of this country". The Committee's hearings into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted from February 11 to March 10, 1919, developed an alarming image of Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

as an imminent threat to the U.S. government and American values. The Committee's final report appeared in June 1919.

Archibald E. Stevenson, a New York attorney with ties to the Justice Department

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

, probably as a "volunteer spy", testified on January 22, 1919, during the German phase of the subcommittee's work. He established that anti-war and anti-draft activism during World War I, which he described as pro-German activity, had now transformed itself into propaganda "developing sympathy for the Bolshevik movement". America's wartime enemy, though defeated, had exported an ideology that now ruled Russia and threatened America anew. "The Bolshevik movement is a branch of the revolutionary socialism of Germany. It had its origin in the philosophy of Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and its leaders were Germans." He cited the propaganda efforts of John Reed and gave many examples from the foreign press. He told the senators that "We have found money coming into this country from Russia."

The senators were particularly interested in how Bolshevism had united many disparate elements on the left, including anarchists and socialists of many types, "providing a common platform for all these radical groups to stand on".United States Congress, ''Bolshevik Propaganda'', 34 Senator Knute Nelson

Knute Nelson (born Knud Evanger; February 2, 1843 – April 28, 1923) was a Norway, Norwegian-born United States, American attorney and politician active in Wisconsin and Minnesota. A Republican Party (United States), Republican, he served in sta ...

, Republican of Minnesota, responded by enlarging Bolshevism's embrace to include an even larger segment of political opinion: "Then they have really rendered a service to the various classes of progressives and reformers that we have here in this country." Other witnesses described the horrors of the revolution in Russia and the consequences of a comparable revolution in the United States: the imposition of atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the Existence of God, existence of Deity, deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the ...

, the seizure of newspapers, assaults on banks, and the abolition of the insurance industry. The senators heard various views of women in Russia, including claims that women had been made the property of the state.

The press reveled in the investigation and the final report, referring to the Russians as "assassins and madmen", "human scum", "crime mad", and "beasts". The occasional testimony by some who viewed the Bolshevik Revolution favorably lacked the punch of its critics. One extended headline in February read:

On the release of the final report, newspapers printed sensational articles with headlines in capital letters: "Red Peril Here", "Plan Bloody Revolution", and "Want Washington Government Overturned".

Anarchist bombings

There were several anarchist bombings in 1919.April 1919 mail bombs

In late April 1919, approximately 36 booby trap bombs were mailed to prominent politicians, including the Attorney General of the United States, judges, businessmen (including

In late April 1919, approximately 36 booby trap bombs were mailed to prominent politicians, including the Attorney General of the United States, judges, businessmen (including John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

), and a Bureau of Investigation field agent, R. W. Finch, who happened to be investigating the ''Galleanist'' organization.

The bombs were mailed in identical packages and were timed to arrive on May Day, the day of celebration of organized labor and the working class. A few of the packages went undelivered because they lacked sufficient postage. One bomb intended for Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson, who had opposed the Seattle General Strike, arrived early and failed to explode as intended. Seattle police in turn notified the Post Office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letter (message), letters and parcel (package), parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post o ...

and other police agencies. On April 29, a package sent to U.S. Senator Thomas W. Hardwick of Georgia, a sponsor of the Anarchist Exclusion Act, exploded injuring his wife and housekeeper. On April 30, a post office employee in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

recognized sixteen packages by their wrapping and interrupted their delivery. Another twelve bombs were recovered before reaching their targets.

June 1919 bombs

In June 1919, eight bombs, far larger than those mailed in April, exploded almost simultaneously in several U.S. cities. These new bombs were believed to contain up to twenty-five pounds of dynamite,"Plotter Here Hid Trail Skillfully; His Victim Was a Night Watchman", ''The New York Times'', June 4, 1919"Wreck Judge Nott's Home", ''The New York Times'', June 3, 1919 and all were wrapped or packaged with heavy metal slugs designed to act as shrapnel. All of the intended targets had participated in some way with the investigation of or the opposition to anarchist radicals. Along with Attorney General Palmer, who was targeted a second time, the intended victims included a Massachusetts state representative and a New Jersey silk manufacturer. Fatalities included a New York City night watchman, William Boehner, and one of the bombers, Carlo Valdinoci, a Galleanist radical who died in spectacular fashion when the bomb he placed at the home of Attorney General Palmer exploded in his face. Though not seriously injured, Attorney General Palmer and his family were thoroughly shaken by the blast, and their home was largely demolished. All of the bombs were delivered with pink flyers bearing the title "Plain Words" that accused the intended victims of waging class war and promised: "We will destroy to rid the world of your tyrannical institutions." Police and the Bureau of Investigation tracked the flyer to a print shop owned by an anarchist, Andrea Salcedo, but never obtained sufficient evidence for a prosecution. Evidence from Valdonoci's death, bomb components, and accounts from participants later tied both bomb attacks to the Galleanists. Though some of the Galleanists were deported or left the country voluntarily, attacks by remaining members continued until 1932.May Day 1919

The American labor movement had been celebrating itsMay Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

holiday since the 1890s and had seen none of the violence associated with the day's events in Europe.Murray, 74 On May 1, 1919, the left mounted especially large demonstrations, and violence greeted the normally peaceful parades in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, and Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

. In Boston, police tried to stop a march that lacked a permit. In the ensuing melee both sides fought for possession of the Socialists' red flags. One policeman was shot and died of his wounds; a second officer died of a heart attack. William Sidis was arrested. Later a mob attacked the Socialist headquarters. Police arrested 114, all from the Socialist side. Each side's newspapers provided uncritical support to their own the next day. In New York, soldiers in uniform burned printed materials at the Russian People's House and forced immigrants to sing the ''Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written by American lawyer Francis Scott Key on September 14, 1814, after he witnessed the bombardment of For ...

''.

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–United States border, Canada–U.S. maritime border ...

saw the worst violence. Leftists protesting the imprisonment of Eugene V. Debs and promoting the campaign of Charles Ruthenberg, the Socialist candidate for mayor, planned to march through the center of the city. A group of Victory Loan workers, a nationalist organization whose members sold war bonds

War bonds (sometimes referred to as victory bonds, particularly in propaganda) are debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war without raising taxes to an unpopular level. They are ...

and thought themselves still at war against all forms of anti-Americanism, tried to block some of the marchers and a melee ensued. A mob ransacked Ruthenberg's headquarters. Mounted police, army trucks, and tanks restored order. Two people died, forty were injured, and 116 arrested. Local newspapers noted that only 8 of those arrested were born in the United States. The city government immediately passed laws to restrict parades and the display of red flags.

With few dissents, newspapers blamed the May Day marchers for provoking the nationalists' response. The Salt Lake City ''Tribune'' did not think anyone had a right to march. It said: "Free speech has been carried to the point where it is an unrestrained menace." A few, however, thought the marches were harmless and that the marchers' enthusiasm would die down on its own if they were left unmolested.

Race riots

More than two dozen American communities, mostly urban areas or industrial centers, saw racial violence in the summer and early fall of 1919. Unlike earlier race riots in U.S. history, the 1919 riots were among the first in which blacks responded with resistance to white attacks.Martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

was imposed in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, This newspaper article includes several paragraphs of editorial analysis followed by Dr. Haynes' report, "summarized at several points". where men of the U.S. Navy led a race riot on May 10. Five white men and eighteen black men were injured in the riot. An official investigation found that four U.S. sailors and one civilian—all white men—were responsible for the outbreak of violence.Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton. ''Encyclopedia of American Race Riots''. Volume 1. 2007, pp. 92–93. On July 3, the 10th U.S. Cavalry, a segregated African American unit founded in 1866, was attacked by local police in Bisbee, Arizona

Bisbee is a city in and the county seat of Cochise County, Arizona, Cochise County in southeastern Arizona, United States. It is southeast of Tucson, Arizona, Tucson and north of the Mexican border. According to the 2020 United States census, ...

. Two of the most violent episodes occurred in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

. In Washington, D.C., white men, many in military uniforms, responded to the rumored arrest of a black man for rape with four days of mob violence, rioting and beatings of random black people on the street. When police refused to intervene, the black population fought back. When the violence ended, ten whites were dead, including two police officers, and 5 blacks. Some 150 people had been the victims of attacks. The rioting in Chicago started on July 27. Chicago's beaches along Lake Michigan were segregated in practice, if not by law. A black youth who drifted into the area customarily reserved for whites was stoned and drowned. Blacks responded violently when the police refused to take action. Violence between mobs and gangs lasted 13 days. The resulting 38 fatalities included 23 blacks and 15 whites. Injuries numbered 537 injured, and 1,000 black families were left homeless. Some 50 people were reported dead. Unofficial numbers were much higher. Hundreds of mostly black homes and businesses on the South Side were destroyed by mobs, and a militia force of several thousand was called in to restore order.

In mid-summer, in the middle of the Chicago riots, a "federal official" told the ''New York Times'' that the violence resulted from "an agitation, which involves the I.W.W., Bolshevism and the worst features of other extreme radical movements". He supported that claim with copies of negro publications that called for alliances with leftist groups, praised the Soviet regime, and contrasted the courage of jailed Socialist Eugene V. Debs with the "school boy rhetoric" of traditional black leaders. The ''Times'' characterized the publications as "vicious and apparently well financed," mentioned "certain factions of the radical Socialist elements", and reported it all under the headline: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt".

In mid-October, government sources again provided the ''New York Times'' with evidence of Bolshevist propaganda targeting America's black communities that was "paralleling the agitation that is being carried on in industrial centres of the North and West, where there are many alien laborers". Vehicles for this propaganda about the "doctrines of Lenin and Trotzky" included newspapers, magazines, and "so-called 'negro betterment' organizations". Quotations from such publications contrasted the recent violence in Chicago and Washington, D.C., with "Soviet Russia, a country in which dozens of racial and lingual types have settled their many differences and found a common meeting ground, a country which no longer oppresses colonies, a country from which the lynch rope is banished and in which racial tolerance and peace now exist." The ''New York Times'' cited one publication's call for unionization: "Negroes must form cotton workers' unions. Southern white capitalists know that the negroes can bring the white bourbon South to its knees. So go to it."

Strikes

Boston police strike

TheAmerican Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL) began granting charters to police unions in June 1919 when pressed to do so by local groups, and in just 5 months had recognized affiliate police unions in 37 cities. The Boston Police rank and file went out on strike on September 9, 1919 in order to achieve recognition for their union and improvements in wages and working conditions. Police Commissioner Edwin Upton Curtis denied that police officers had any right to form a union, much less one affiliated with a larger organization like the AFL. During the strike, Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

experienced two nights of lawlessness until several thousand members of the State Guard supported by volunteers restored order, though not without causing several deaths. The public, fed by lurid press accounts and hyperbolic political observers, viewed the strike with a degree of alarm out of proportion to the events, which ultimately produced only about $35,000 of property damage.

The strikers were called "deserters" and "agents of Lenin." The Philadelphia ''Public Ledger'' viewed the Boston violence in the same light as many other of 1919's events: "Bolshevism in the United States is no longer a specter. Boston in chaos reveals its sinister substance." President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, speaking from Montana, branded the walkout "a crime against civilization" that left the city "at the mercy of an army of thugs". The timing of the strike also happened to present the police union in the worst light. September 10, the first full day of the strike, was also the day a huge New York City parade celebrated the return of General John J. Pershing, the hero of the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

.

A report from Washington, D.C., included this headline: "Senators Think Effort to Sovietize the Government Is Started". Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

saw in the strike the dangers of the national labor movement: "If the American Federation of Labor succeeds in getting hold of the police in Boston it will go all over the country, and we shall be in measurable distance of Soviet government by labor unions." The ''Ohio State Journal'' opposed any sympathetic treatment of the strikers: "When a policeman strikes, he should be debarred not only from resuming his office, but from citizenship as well. He has committed the unpardonable sin; he has forfeited all his rights."

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

of the AFL recognized that the strike was damaging labor in the public mind and advised the strikers to return to work. The Police Commissioner, however, remained adamant and refused to re-hire the striking policemen. He was supported by Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

, whose rebuke of Gompers earned him a national reputation. Famous as a man of few words, he put the anti-union position simply: "There is no right to strike against the public safety, anywhere, anytime."

The strike proved another setback for labor and the AFL immediately withdrew its recognition of police unions. Coolidge won the Republican nomination for Vice-President in the 1920 presidential election in part due to his actions during the Boston Police Strike.

1918–1920 New York City rent strikes

Following a housing and coal shortage caused by the mobilization for World War I, a wave of rent strikes occurred across all of New York City andJersey City

Jersey City is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, second-most populous

from 1918 to 1920. While it is unclear exactly how many tenants were involved, at least tens of thousands and likely hundreds of thousands tenants struck.

In response to the strikes, which was marked heavily by the Red Scare, rhetoric accusing tenant leaders of being Bolsheviks and comments that claimed a fear that there would be a mass uprising were commonly invoked by political officials at the time. Repression by the government was also prevalent; two examples include the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchist ...

and Lusk Committee raids. The period was also marked by anti-Semitic rhetoric.

In 1920, the five Socialist members of the New York state assembly were expelled from it by a vote of 140 to 6, partially in response to their support for the strikes.

By its end, the wave of strikes had led to the passage of the first rent laws in the country and fundamentally shifted tenant-landlord relations. However, the more radical tenant groups largely were destroyed by raids or slowly dwindled as a result of the new laws addressing the crisis.

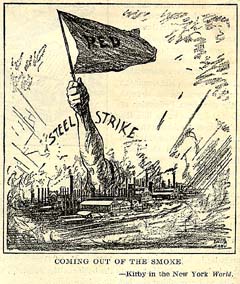

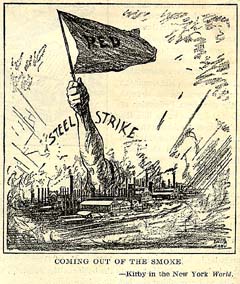

Steel strike of 1919

Though the leadership of the

Though the leadership of the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL) opposed a strike in the steel industry, 98% of their union members voted to strike beginning on September 22, 1919. It shut down half the steel industry, including almost all mills in Pueblo, Colorado

Pueblo ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Home rule municipality, home rule municipality that is the county seat of and the List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous municipality in Pueblo County, Colorado, United States. The ...

; Chicago, Illinois

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

; Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in Ohio County, West Virginia, Ohio and Marshall County, West Virginia, Marshall counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The county seat of Ohio County, it lies along the Ohio River in the foothills of the Appalachian Mo ...

; Johnstown, Pennsylvania

Johnstown is the largest city in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 18,411 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located east of Pittsburgh, it is the principal city of the Metropolitan statistical area ...

; Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–United States border, Canada–U.S. maritime border ...

; Lackawanna, New York

Lackawanna is a city in Erie County, New York, United States, just south of the city of Buffalo in western New York State. The population was 19,949 at the 2020 census. It is one of the fastest-growing cities in New York, growing in populati ...

; and Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in Mahoning County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Ohio, 11th-most populous city in Ohio with a population of 60,068 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Mahoning ...

.

The owners quickly turned public opinion against the AFL. As the strike began, they published information exposing AFL National Committee co-chairman William Z. Foster's radical past as a Wobbly and syndicalist

Syndicalism is a labour movement within society that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes and other forms of direct action, with the eventual goal of gainin ...

, and claimed this was evidence that the steelworker strike was being masterminded by radicals and revolutionaries. The steel companies played on nativist fears by noting that a large number of steelworkers were immigrants. Public opinion quickly turned against the striking workers. State and local authorities backed the steel companies. They prohibited mass meetings, had their police attack pickets and jailed thousands. After strikebreakers and police clashed with unionists in Gary, Indiana

Gary ( ) is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. The population was 69,093 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it Indiana's List of municipalities in Indiana, eleventh-most populous city. The city has been historical ...

, the U.S. Army took over the city on October 6, 1919, and martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

was declared. National Guardsmen, leaving Gary after federal troops had taken over, turned their anger on strikers in nearby Indiana Harbor, Indiana.

Steel companies also turned toward strikebreaking and rumor-mongering to demoralize the picketers. They brought in between 30,000 and 40,000 African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

and Mexican-American

Mexican Americans are Americans of full or partial Mexican descent. In 2022, Mexican Americans comprised 11.2% of the US population and 58.9% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexican Americans were born in the United State ...

workers to work in the mills. Company spies also spread rumors that the strike had collapsed elsewhere, and they pointed to the operating steel mills as proof that the strike had been defeated.

Congress conducted its own investigation, focused on radical influence upon union activity. In that context, U.S. Senator Kenneth McKellar, a member of the Senate committee investigating the strike, proposed making one of the Philippine Islands a penal colony to which those convicted of an attempt to overthrow the government could be deported.

The Chicago mills gave in at the end of October. By the end of November, workers were back at their jobs in Gary, Johnstown, Youngstown, and Wheeling. The strike collapsed on January 8, 1920, though it dragged on in isolated areas like Pueblo and Lackawanna.

Coal strike of 1919

TheUnited Mine Workers

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American Labor history of the United States, labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing work ...

under John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of Labor unions in the United States, organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers, United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. ...

announced a strike for November 1, 1919. They had agreed to a wage agreement to run until the end of World War I and now sought to capture some of their industry's wartime gains. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer invoked the Lever Act, a wartime measure that made it a crime to interfere with the production or transportation of necessities. The law, meant to punish hoarding and profiteering, had never been used against a union. Certain of united political backing and almost universal public support, Palmer obtained an injunction on October 31 and 400,000 coal workers went on strike the next day. He claimed the President authorized the action, following a meeting with the severely ill President in the presence of his doctor. Palmer also asserted that the entire Cabinet had backed his request for an injunction. That infuriated Secretary of Labor Wilson who had opposed Palmer's plan and supported Gompers' view of the President's promises when the Act was under consideration. The rift between the Attorney General and the Secretary of Labor was never healed, which had consequences the next year when Palmer's attempts to deport radicals were frustrated by the Department of Labor.

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, President of the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

, protested that President Wilson and members of his Cabinet had provided assurances when the Act was passed that it would not be used to prevent strikes by labor unions. He provided detailed accounts of his negotiations with representatives of the administration, especially Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson. He also argued that the end of hostilities, even in the absence of a signed treaty, should have invalidated any attempts to enforce the Act's provisions. Nevertheless, he attempted to mediate between Palmer and Lewis, but after several days called the injunction "so autocratic as to stagger the human mind". The coal operators smeared the strikers with charges that Lenin and Trotsky had ordered the strike and were financing it, and some of the press echoed that language.Murray, 155 Others used words like "insurrection" and "Bolshevik revolution". Eventually Lewis, facing criminal charges and sensitive to the propaganda campaign, withdrew his strike call, though many strikers ignored his action. As the strike dragged on into its third week, coal supplies were running low and public sentiment was calling for ever stronger government action. Final agreement came on December 10.

Reactions

Palmer Raids

Despite two attempts on his life in April and June 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer moved slowly to find a way to attack the source of the violence. An initial raid in July 1919 against a small anarchist group in Buffalo failed when a federal judge tossed out his case. In August, he organized the General Intelligence Division within the Department of Justice and recruited

Despite two attempts on his life in April and June 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer moved slowly to find a way to attack the source of the violence. An initial raid in July 1919 against a small anarchist group in Buffalo failed when a federal judge tossed out his case. In August, he organized the General Intelligence Division within the Department of Justice and recruited J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

, a recent law school graduate, to head it. Hoover pored over arrest records, subscription records of radical newspapers, and party membership records to compile lists of resident aliens for deportation proceedings. On October 17, 1919, just a year after the Immigration Act of 1918 had expanded the definition of aliens that could be deported, the U.S. Senate demanded Palmer explain his failure to move against radicals.

Palmer launched his campaign against radicalism with two sets of police actions known as the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchist ...

in November 1919 and January 1920. Federal agents supported by local police rounded up large groups of suspected radicals, often based on membership in a political group rather than any action taken. Undercover informants and warrantless wiretaps (authorized under the Sedition Act) helped to identify several thousand suspected leftists and radicals to be arrested.

Only the dismissal of most of the cases by Acting United States Secretary of Labor Louis Freeland Post limited the number of deportations to 556. Fearful of extremist violence and revolution, the American public supported the raids. Civil libertarians, the radical left, and legal scholars raised protests. Officials at the Department of Labor, especially Post, asserted the rule of law in opposition to Palmer's anti-radical campaign. Post faced a Congressional threat to impeach or censure him. He successfully defended his actions in two days of testimony before the House Rules Committee in June 1919 and no action was ever taken against him. Palmer testified before the same committee, also for two days, and stood by the raids, arrests, and deportation program. Much of the press applauded Post's work at Labor, while Palmer, rather than President Wilson, was largely blamed for the negative aspects of the raids.

Deportations

On December 21, 1919, the ''Buford'', a ship the press nicknamed the "Soviet Ark", left New York harbor with 249 deportees. Of those, 199 had been detained in the November

On December 21, 1919, the ''Buford'', a ship the press nicknamed the "Soviet Ark", left New York harbor with 249 deportees. Of those, 199 had been detained in the November Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchist ...

, with 184 of them deported because of their membership in the Union of Russian Workers

The Union of Russian Workers in the United States and Canada, commonly known as the "Union of Russian Workers" (Союз Русских Рабочих, ''Soiuz Russkikh Rabochikh)'' was an anarcho-syndicalist union of Russian American, Russian em ...

, an anarchist group that was a primary target of the November raids. Others on board, including the well-known radical leaders Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

and Alexander Berkman, had not been taken in the Palmer Raids. Goldman had been convicted in 1893 of "inciting to riot" and arrested on many other occasions. Berkman had served 14 years in prison for the attempted murder of industrialist Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company and played a major ...

in 1892. Both were convicted in 1917 of interfering with military recruitment. Some of the 249 were leftists or anarchists or at least fell within the legal definition of anarchist because they "believed that no government would be better for human society than any kind of government". In beliefs they ranged from violent revolutionaries to pacifist advocates of non-resistance. Others belonged to radical organizations but disclaimed knowledge of the organization's political aims and had joined to take advantage of educational programs and social opportunities.

The U.S. War Department used the ''Buford'' as a transport ship in the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

and in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and loaned it to the Department of Labor

A ministry of labour (''British English, UK''), or labor (''American English, US''), also known as a department of labour, or labor, is a government department responsible for setting labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workfor ...

in 1919 for the deportation mission. A "strong detachment of marines" numbering 58 enlisted men and four officers made the journey and pistols were distributed to the crew. Its final destination was unknown as it sailed under sealed orders. Even the captain only learned his final destination while in Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

harbor for repairs, since the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

found it difficult to make arrangements to land in Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

. Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, though chosen, was not an obvious choice, since Finland and Russia were at war.

The notoriety of Goldman and Berkman as convicted anti-war agitators allowed the press and public to imagine that all the deportees had similar backgrounds. ''The New York Times'' called them all "Russian Reds". Most of the press approved enthusiastically. The Cleveland ''Plain Dealer'' wrote: "It is hoped and expected that other vessels, larger, more commodious, carrying similar cargoes, will follow in her wake." The ''New York Evening Mail

The ''New York Evening Mail'' (1867–1924) was an American daily newspaper published in New York City. For a time the paper was the only evening newspaper to have a franchise in the Associated Press.

History Names

The paper was founded as the ' ...

'' said: "Just as the sailing of the Ark that Noah built was a pledge for the preservation of the human race, so the sailing of the Ark of the Soviet is a pledge for the preservation of America." Goldman later wrote a book about her experiences after being deported to Russia, called '' My Disillusionment in Russia''.

=Concentration camps

= As reported by ''The New York Times'', some communists agreed to be deported while others were put into a concentration camp at Camp Upton in New York pending deportation hearings.Expulsion of Socialists from the New York Assembly

On January 7, 1920, at the first session of the

On January 7, 1920, at the first session of the New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature, with the New York State Senate being the upper house. There are 150 seats in the Assembly. Assembly members serve two-year terms without term limits.

The Ass ...

, Assembly Speaker Thaddeus C. Sweet attacked the Assembly's five Socialist members, declaring they had been "elected on a platform that is absolutely inimical to the best interests of the state of New York and the United States". The Socialist Party, Sweet said, was "not truly a political party", but was rather "a membership organization admitting within its ranks aliens, enemy aliens, and minors". It had supported the revolutionaries in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Austria, and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, he continued, and consorted with international Socialist parties close to the Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

.Waldman, 2–7 The Assembly suspended the five by a vote of 140 to 6, with just one Democrat supporting the Socialists.

A trial in the Assembly, lasting from January 20 to March 11, resulted in a recommendation that the five be expelled and the Assembly voted overwhelmingly for expulsion on April 1, 1920. The expulsion was partially in response to their support for and involvement in the wave of rent strikes occurring in NYC.

Opposition to the Assembly's actions was widespread and crossed party lines. From the start of the process, former Republican Governor, Supreme Court Justice, and presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

defended the Socialist members: "Nothing ... is a more serious mistake at this critical time than to deprive Socialists or radicals of their opportunities for peaceful discussion and thus to convince them that the Reds are right and that violence and revolution are the only available means at their command." Democratic Governor Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was the 42nd governor of New York, serving from 1919 to 1920 and again from 1923 to 1928. He was the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party's presidential nominee in the 1 ...

denounced the expulsions: "To discard the method of representative government leads to the misdeeds of the very extremists we denounce and serves to increase the number of enemies of orderly free government." Hughes also led a group of leading New York attorneys in a protest that said: "We have passed beyond the stage in political development when heresy-hunting is a permitted sport."

Coverage

Newspaper coverage

America's newspapers continually reinforced their readers' pro-American views and presented a negative attitude toward the Soviet Union and communism. They presented a threat of imminent conflict with the Soviet Union that would be justified by the clash with American ideals and goals.Kriesberg, Martin. "Soviet News in the ''New York Times''". ''The Public Opinion Quarterly'', Vol. 10. (Winter, 1946–1947): 540–564. JSTOR. 23 October 2014. In addition, when ''The New York Times'' reported positively about the Soviet Union, it received less attention from the public than when it reported antagonistically about it. This did not hold true when Soviet interests agreed with American ones. As a result of this, the ''Times'' had a tendency to use exaggerated headlines, weighted words, and questionable sources in order to create a negative slant against the Soviets and communism. The tendency was to be very pro-American and theatrical in their coverage. The Red Scare led to the Western popularization of ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated text purporting to detail a Jewish plot for global domination. Largely plagiarized from several earlier sources, it was first published in Imperial Russia in 1903, translated into multip ...

''. The text was purportedly brought to the United States by a Russian army officer in 1917; it was translated into English by Natalie de Bogory (personal assistant of Harris A. Houghton, an officer of the Department of War) in June 1918, and White Russian expatriate Boris Brasol soon circulated it in American government circles, specifically diplomatic and military, in typescript form, It also appeared in 1919 in the '' Public Ledger'' as a pair of serialized newspaper articles. But all references to "Jews" were replaced with references to '' Bolsheviki'' as an exposé by the journalist – and subsequently highly respected Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

School of Journalism dean – Carl W. Ackerman. Shortly thereafter it was adapted as "The International Jew

''The International Jew'' is a four-volume set of antisemitic booklets or pamphlets originally published and distributed in the early 1920s by the Dearborn Publishing Company, an outlet owned by Henry Ford, the American industrialist and autom ...

" series in '' The Dearborn Independent'', establishing the myth of Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist conspiracy theory that claims that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a Jewish plot and that Jews controlled the Soviet Union and international communist moveme ...

.

Film

America's film industry reflected and exploited every aspect of the public's fascination with and fear of Bolshevism. ''The German Curse in Russia'' dramatized the German instigation of Russia'sOctober Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. The Soviet nationalization of women was central to the plot of ''The New Moon'', in which women between the ages of 23 and 32 are the property of the state and the heroine, Norma Talmadge

Norma Marie Talmadge (May 2, 1894 – December 24, 1957) was an American actress and film producer of the silent film, silent era. A major box-office draw for more than a decade, her career reached a peak in the early 1920s, when she ranked among ...

, is a Russian princess posing as a peasant during the Russian Revolution. Similarly, in ''The World and Its Woman'' starring Geraldine Farrar, the daughter of an American engineer working in Russia becomes an opera star and has to fend off attempts to "nationalize" her.

Several films used labor troubles as their setting, with an idealistic American hero and heroine struggling to outwit manipulative left-wing agitators. '' Dangerous Hours'' tells the story of an attempted Russian infiltration of American industry. College graduate John King is sympathetic to the left in a general way. Then he is seduced, both romantically and politically, by Sophia Guerni, a female agitator. Her superior is the Bolshevik Boris Blotchi, who has a "wild dream of planting the scarlet seed of terrorism in American soil".Brownlow, 263 Sofia and Boris turn their attention to the Weston shipyards that are managed by John's childhood sweetheart, May. The workers have valid grievances, but the Bolsheviks set out to manipulate the situation. They are "the dangerous element following in the wake of labor as riffraff and ghouls follow an army". When they threaten May, John has an epiphany and renounces revolutionary doctrine.

A reviewer in ''Picture Play'' protested the film's stew of radical beliefs and strategies: "Please, oh please, look up the meaning of the words 'bolshevik' and 'soviet'. Neither of them mean 'anarchist', 'scoundrel' or 'murderer' – really they don't!"

Some films just used Bolsheviks for comic relief, where they are easily seduced (''The Perfect Woman'') or easily inebriated (''Help Yourself''). In ''Bullin the Bullsehviks'' an American named Lotta Nerve outwits Trotsky. New York State Senator Clayton R. Lusk spoke at the film's New York premiere in October 1919. Other films used one feature or another of radical philosophy as the key plot point: anarchist violence (''The Burning Question''), assassination and devotion to the red flag (''The Volcano''), utopian vision ('' Bolshevism on Trial'').

The advertising for ''Bolshevism on Trial'' called it "the timeliest picture ever filmed" and reviews were good. "Powerful, well-knit with indubitably true and biting satire", said ''Photoplay

''Photoplay'' was one of the first American film fan magazines, its title another word for screenplay. It was founded in Chicago in 1911. Under early editors Julian Johnson and James R. Quirk, in style and reach it became a pacesetter for fan m ...

''. As a promotion device, the April 15, 1919, issue of ''Moving Picture World'' suggested staging a mock radical demonstration by hanging red flags around town and then have actors in military uniforms storm in to tear them down. The promoter was then to distribute handbills to the confused and curious crowds to reassure them that ''Bolshevism on Trial'' takes a stand against Bolshevism and "you will not only clean up but will profit by future business". When this publicity technique came to the attention of U.S. Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson, he expressed his dismay to the press: "This publication proposes by deceptive methods of advertising to stir every community in the United States into riotous demonstrations for the purpose of making profits for the moving picture business". He hoped to ban movies treating Bolshevism and Socialism.

Legislation

In 1919, Kansas enacted a law titled "An act relating to the flag, standard or banner of Bolshevism, anarchy or radical socialism" in an attempt to punish the display of the most common symbol of radicalism, the red flag. Only Massachusetts (1913) and Rhode Island (1914) passed such "red flag laws" earlier. By 1920 they were joined by 24 more states.Franklin, 292 Some banned certain colors (red or black), or certain expressions ("indicating disloyalty or belief in anarchy" or "antagonistic to the existing government of the United States"), or certain contexts ("to overthrow the government by general strike"), or insignia ("flag or emblem or sign"). The ''Yale Law Journal'' mocked the Connecticut law against symbols "calculated to ... incite people to disorder", anticipating its enforcement at the next Harvard-Yale football game. Ohio exempted college pennants and Wisconsin made an exception for historical museums. Minnesota allowed red flags for railroad and highway warnings. Setting patriotic standards, red flag laws regulated the proper display of the American flag: above all other flags, ahead of all other banners in any parade, or flown only in association with state flags or the flags of friendly nations. Punishment generally included fines from $1,000 to $5,000 and prison terms of 5 to 10 years, occasionally more. At the federal level, theEspionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code ( ...

and the amendments to it in the Sedition Act of 1918 prohibited interference with the war effort, including many expressions of opinion. With that legislation rendered inoperative by the end of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, supported by President Wilson, waged a public campaign in favor of a peacetime version of the Sedition Act without success.Chafee, 195 He sent a circular outlining his rationale to newspaper editors in January 1919, citing the dangerous foreign-language press and radical attempts to create unrest in African American communities. At one point Congress had more than 70 versions of proposed language and amendments for such a bill, but it took no action on the controversial proposal during the campaign year of 1920.

Palmer called for every state to enact its own version of the Sedition Act. Six states had laws of this sort before 1919 usually aimed at sabotage, but another 20 added them in 1919 and 1920. Usually called "anti-syndicalist laws", they varied in their language, but generally made it a crime to "destroy organized government" by one method or another, including "by the general cessation of industry", that is, through a general strike. Many cities had their own versions of these laws, including 20 in the state of Washington alone.

Demise

May Day 1920

Within Attorney General Palmer's Justice Department, the General Intelligence Division (GID) headed byJ. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

had become a storehouse of information about radicals in America. It had infiltrated many organizations and, following the raids of November 1919 and January 1920, it had interrogated thousands of those arrested and read through boxes of publications and records seized. Though agents in the GID knew there was a gap between what the radicals promised in their rhetoric and what they were capable of accomplishing, they nevertheless told Palmer they had evidence of plans for an attempted overthrow of the U.S. government on May Day 1920.

With Palmer's backing, Hoover warned the nation to expect the worst: assassinations, bombings, and general strikes. Palmer issued his own warning on April 29, 1920, claiming to have a "list of marked men" and said domestic radicals were "in direct connection and unison" with European counterparts with disruptions planned for the same day there. Newspapers headlined his words: "Terror Reign by Radicals, says Palmer" and "Nation-wide Uprising on Saturday". Localities prepared their police forces and some states mobilized their militias. New York City's 11,000-man police force worked for 32 hours straight. Boston police mounted machine guns on automobiles and positioned them around the city.

The date came and went without incident. Newspaper reaction was almost uniform in its mockery of Palmer and his "hallucinations". Clarence Darrow