Execution By Firing Squad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'',

The method is often the capital punishment or disciplinary means employed by military courts for crimes such as cowardice,

The method is often the capital punishment or disciplinary means employed by military courts for crimes such as cowardice,

Manuel Dorrego, a prominent Argentine statesman and soldier who governed Buenos Aires in the 1820s, was executed by firing squad on 12 December 1828 after being defeated in battle by Juan Lavalle and later convicted of treason.

Manuel Dorrego, a prominent Argentine statesman and soldier who governed Buenos Aires in the 1820s, was executed by firing squad on 12 December 1828 after being defeated in battle by Juan Lavalle and later convicted of treason.

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the

The death penalty was widely used during and after the

The death penalty was widely used during and after the

The New Zealand government

Ben Fenton, August 16, 2006, accessed October 14, 2006 On 15 October 1917 Dutch exotic dancer

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as

The

The

During the

During the  John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the University of Utah School of Medicine, at his request.

Since 1960 there have been four executions by firing squad, all in

John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the University of Utah School of Medicine, at his request.

Since 1960 there have been four executions by firing squad, all in

Firing Squad Execution of a Civil War Deserter Described in an 1861 Newspaper

* ttp://www.thefirstpost.co.uk/64684,in-pictures,news-in-pictures,death-by-firing-squad Death by Firing Squadnbsp;– slideshow by '' The First Post''

Nazis Meet the Firing Squad

– slideshow by ''

rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

), is a method of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

, particularly common in the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

s are usually readily available and a gunshot to a vital organ

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

, such as the brain or heart, most often will kill relatively quickly.

A firing squad is normally composed of several soldiers, all of whom are usually instructed to fire simultaneously, thus preventing both disruption of the process by one member and identification of who fired the lethal shot. To avoid disfigurement due to multiple shots to the head, the shooters are typically instructed to aim at the heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as ca ...

, sometimes aided by a paper or cloth target. The prisoner is typically blindfolded or hooded

A hood is a kind of headgear that covers most of the head and neck, and sometimes the face. Hoods that cover mainly the sides and top of the head, and leave the face mostly or partly open may be worn for protection from the environment (typica ...

as well as restrained. Media portrayals have frequently shown the condemned being offered a final cigarette

A cigarette is a narrow cylinder containing a combustible material, typically tobacco, that is rolled into thin paper for smoking. The cigarette is ignited at one end, causing it to smolder; the resulting smoke is orally inhaled via the opp ...

as well. Executions can be carried out with the condemned either standing or sitting. There is a tradition in some jurisdictions that such executions are carried out at first light or at sunrise. This gave rise to the phrase "shot at dawn".

Execution by firing squad is a specific practice that is distinct from other forms of execution by firearms, such as an execution by shot(s) to the back of the head or neck. However, the single shot by the squad's officer with a pistol ( coup de grâce) is sometimes incorporated in a firing squad execution, particularly if the initial volley turns out not to be immediately fatal. Before the introduction of firearms, bows or crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar ...

s were often used—Saint Sebastian

Saint Sebastian (in Latin: ''Sebastianus''; Narbo, Gallia Narbonensis, Roman Empire c. AD 255 – Rome, Italia, Roman Empire c. AD 288) was an early Christian saint and martyr. According to traditional belief, he was killed during the Diocle ...

is usually depicted as executed by a squad of Roman auxiliary

The (, lit. "auxiliaries") were introduced as non-citizen troops attached to the citizen legions by Augustus after his reorganisation of the Imperial Roman army from 30 BC. By the 2nd century, the Auxilia contained the same number of in ...

archers in around AD 288; King Edmund the Martyr

Edmund the Martyr (also known as St Edmund or Edmund of East Anglia, died 20 November 869) was king of East Anglia from about 855 until his death.

Few historical facts about Edmund are known, as the kingdom of East Anglia was devastated by t ...

of East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, by some accounts, was tied to a tree and executed by Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

archers on 20 November 869 or 870.

Military significance

The method is often the capital punishment or disciplinary means employed by military courts for crimes such as cowardice,

The method is often the capital punishment or disciplinary means employed by military courts for crimes such as cowardice, desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or Military base, post without permission (a Pass (military), pass, Shore leave, liberty or Leave (U.S. military), leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with u ...

, espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

, murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the ...

, mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among memb ...

, or treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

.

If the condemned prisoner is an ex-officer who is acknowledged to have shown bravery throughout their career, they may be afforded the privilege of giving the order to fire. An example of this is Marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished ( ...

Michel Ney. As a means of insulting the condemned, however, past executions have had them shot in the back, denied blindfolds, or even tied to chairs. When Galeazzo Ciano, son-in-law of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

, and several other former Fascists who voted to remove Mussolini from power were executed, they were tied to chairs facing away from their executioners. By some reports, Ciano managed to twist his chair around at the last second to face them.

Blank cartridge

Sometimes, one or more soldiers of the firing squad may be issued a rifle containing ablank cartridge

A blank is a firearm cartridge that, when fired, does not shoot a projectile like a bullet or pellet, but generates a muzzle flash and an explosive sound ( muzzle report) like a normal gunshot would. Firearms may need to be modified to allow a b ...

. In such cases, soldiers of the firing squad are not told beforehand whether they are using live ammunition. This is believed to reinforce the sense of diffusion of responsibility

Diffusion of responsibility is a sociopsychological phenomenon whereby a person is less likely to take responsibility for action or inaction when other bystanders or witnesses are present. Considered a form of attribution, the individual assume ...

among the firing squad members. It provides each member with a measure of plausible deniability that they, personally, did not fire a bullet at all. For this reason, it is sometimes referred to as the "conscience round".

In practice however, firing a live round produces significant recoil, while firing a blank does not. This is especially significant with bolt-action rifles. As a result, it is not realistic to assume that, after the fact, trained soldiers will be unaware of which they shot. This is reflected in first-hand reports such as Pte. W. A. Quinton’s, who served in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and served on a firing squad in October 1915. Per his account, he and 11 colleagues were relieved of any live ammunition and their own rifles, then issued replacement firearms for the task at hand. After a short speech by an officer, the squad fired a volley at the condemned man. Quinton stated that "I had the satisfaction of knowing that as soon as I fired, the absence of any recoil ndicatedthat I had merely fired a blank cartridge".

In more recent times, such as the 2010 execution of Ronnie Lee Gardner

Ronnie Lee Gardner (January 16, 1961 – June 18, 2010) was an American criminal who received the death penalty for killing a man during an attempted escape from a courthouse in 1985, and was executed by a firing squad by the state of Utah in 20 ...

in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

, USA, one rifleman may be given a "dummy" cartridge containing a wax bullet, which provides a more realistic recoil.

By country

Argentina

Manuel Dorrego, a prominent Argentine statesman and soldier who governed Buenos Aires in the 1820s, was executed by firing squad on 12 December 1828 after being defeated in battle by Juan Lavalle and later convicted of treason.

Manuel Dorrego, a prominent Argentine statesman and soldier who governed Buenos Aires in the 1820s, was executed by firing squad on 12 December 1828 after being defeated in battle by Juan Lavalle and later convicted of treason.

Belgium

On 12 October 1915 a British nurseEdith Cavell

Edith Louisa Cavell ( ; 4 December 1865 – 12 October 1915) was a British nurse. She is celebrated for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination and for helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Be ...

was executed by a German firing squad at the Tir national

The National shooting range (french: Tir national, nl, Nationale Schietbaan) was a firing range and military training complex of situated in the municipality of Schaerbeek in Brussels. During World Wars I and II the site was used for the execu ...

shooting range at Schaerbeek after being convicted of "conveying troops to the enemy" during the First World War.

On 1 April 1916 a Belgian woman, Gabrielle Petit

Gabrielle Alina Eugenia Maria Petit (20 February 1893 – 1 April 1916) was a Belgian woman who spied for the British Secret Service during World War I. She was executed in 1916, and became a Belgian national heroine after the war's end.

, was executed by a German firing squad at Schaerbeek after being convicted of spying for the British Secret Service during World War I.

During the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

in World War II, three captured German spies were tried and executed by a U.S. firing squad at Henri-Chapelle

Henri-Chapelle ( wa, Hinri-Tchapele, nl, Hendrik-Kapelle, german: Heinrichskapelle, li, Kapäl) is a village of Wallonia and a district of the municipality of Welkenraedt, located in the province of Liège, Belgian.

It is located 17 kilomete ...

on 23 December 1944. Thirteen other Germans were also tried and shot at either Henri-Chapelle or Huy.Pallud, p. 15 These executed spies took part in Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

commando Otto Skorzeny

Otto Johann Anton Skorzeny (12 June 1908 – 5 July 1975) was an Austrian-born German SS-''Obersturmbannführer'' (lieutenant colonel) in the Waffen-SS during World War II. During the war, he was involved in a number of operations, including t ...

's Operation Greif, in which English-speaking German commandos operated behind U.S. lines, masquerading in U.S. uniforms and equipment.

Brazil

The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 expressly prohibits the usage of capital punishment in peacetime, but authorizes the use of the death penalty for military crimes committed during wartime. War needs to be declared formally, in accordance with international law and article 84, item 19 of the Federal Constitution, with due authorization from the Brazilian Congress. The Brazilian Code of Military Penal Law, in its chapter dealing with wartime offences, specifies the crimes that are subject to the death penalty. The death penalty is never the only possible sentence for a crime, and the punishment must be imposed by the military courts system. Per the norms of the Brazilian Code of Military Penal Procedure, the death penalty is carried out by firing squad. Although Brazil still permits the use of capital punishment during wartime, no convicts were actually executed during Brazil's last military conflict, the Second World War. The military personnel sentenced to death during World War II had their sentences reduced by the President of the Republic.Chile

Following the military overthrow of the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende in 1973, Chilean dictatorAugusto Pinochet

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte (, , , ; 25 November 1915 – 10 December 2006) was a Chilean general who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, first as the leader of the Military Junta of Chile from 1973 to 1981, being declared President of ...

initiated a series of war tribunal trials against leftist people around the country. During the first months after his coup, hundreds of people were killed by firing squads and summary executions.

Cuba

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the

Cuba, as part of its penal system, still utilizes death by firing squad, although the last recorded execution was in 2003. In January 1992 a Cuban exile convicted of "terrorism, sabotage and enemy propaganda" was executed by firing squad. The Council of the State noted that the punishment served as a deterrent and stated that the death penalty "fulfills a goal of overall prevention, especially when the idea is to stop such loathsome actions from being repeated, to deter others and so to prevent innocent human lives from being endangered in the future".

During the months following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in co ...

in 1959, soldiers of the Batista government and political opponents to the revolution were executed by firing squad.

Finland

The death penalty was widely used during and after the

The death penalty was widely used during and after the Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''Aamulehti'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil W ...

(January–May 1918); some 9,700 Finns and an unknown number of Russian volunteers on Red side were executed during the war or in its aftermath. Most executions were carried out by firing squads after the sentences were given by illegal or semi-legal courts martial. Only some 250 persons were sentenced to death in courts acting on legal authority.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

some 500 persons were executed, half of them condemned spies. The usual causes for death penalty for Finnish citizens were treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and high treason (and to a lesser extent cowardice and disobedience, applicable for military personnel). Almost all cases of capital punishment were tried by court-martial. Usually the executions were carried out by the regimental military police platoon, or by the local military police in the case of spies. One Finn, Toivo Koljonen, was executed for a civilian crime (six murders). Most executions occurred in 1941 and during the Soviet Summer Offensive in 1944. The last death sentences were given in 1945 for murder, but later commuted to life imprisonment.

The death penalty was abolished by Finnish law in 1949 for crimes committed during peacetime, and in 1972 for all crimes. Finland is party to the Optional protocol of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, fre ...

, forbidding the use of the death penalty in all circumstances.

France

Pte.Thomas Highgate

Private Thomas James Highgate (13 May 1895 – 8 September 1914) was a British soldier during World War I and the first British soldier to be convicted of desertion and executed by firing squad. He was born in Shoreham and worked as a farm ...

was the first British soldier to be convicted of desertion and executed by firing squad in September 1914 at Tournan-en-Brie during World War I. In October 1916 Pte. Harry Farr

Private Harry T. Farr (1891 – 18 October 1916) was a British soldier who was executed by firing squad during World War I for cowardice at the age of 25. Before the war, he lived in Kensington, London and joined the British Army in 1908. He ...

was shot for cowardice at Carnoy, which was later suspected to be acoustic shock

Acoustic shock is the set of symptoms a person may experience after hearing an unexpected, loud sound. The loud sound, called an acoustic incident, can be caused by feedback oscillation, fax tones, or signalling tones. Telemarketers and call cen ...

. Highgate and Farr, along with 304 other British and Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas

...

troops who were executed for similar offenses, were listed at the Shot at Dawn Memorial

The Shot at Dawn Memorial is a monument at the National Memorial Arboretum near Alrewas, in Staffordshire, UK. It commemorates the 306 British Army and Commonwealth soldiers executed after courts-martial for desertion and other capital offences ...

which was erected to honor them.The Shot at Dawn CampaignThe New Zealand government

pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

ed its troops in 2000; the British government in 1998 expressed sympathy for the executed and in 2006 the Secretary of State for Defence

The secretary of state for defence, also referred to as the defence secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the business of the Ministry of Defence. The incumbent is a membe ...

announced a full pardon for all 306 executed soldiers from the First World War.The Daily TelegraphBen Fenton, August 16, 2006, accessed October 14, 2006 On 15 October 1917 Dutch exotic dancer

Mata Hari

Margaretha Geertruida MacLeod (née Zelle; 7 August 187615 October 1917), better known by the stage name Mata Hari (), was a Dutch exotic dancer and courtesan who was convicted of being a spy for Germany during World War I. She was executed ...

was executed by a French firing squad at Château de Vincennes

The Château de Vincennes () is a former fortress and royal residence next to the town of Vincennes, on the eastern edge of Paris, alongside the Bois de Vincennes. It was largely built between 1361 and 1369, and was a preferred residence, afte ...

castle in the town of Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

after being convicted of spying for Germany during World War I.

During World War II, on 24 September 1944, Josef Wende and Stephan Kortas, two Poles drafted into the German army, crossed the Moselle Rivers behind U.S. lines in civilian clothes to observe Allied strength and were to rejoin their own army on the same day. However, they were discovered by the Americans and arrested. On 18 October 1944 they were found guilty of espionage by a U.S. military commission and sentenced to death. On 11 November 1944 they were shot in the garden of a farmhouse at Toul

Toul () is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in north-eastern France.

It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

Geography

Toul is between Commercy and Nancy, and the river Moselle and Canal de la Marne au Rhin.

Climate

Toul ...

. The footage of Wende's execution as well as Kortas's is shown in these links.

On 31 January 1945, U.S. Army Pvt. Edward "Eddie" Slovik was executed by firing squad for desertion near the village of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. He was the first American soldier executed for such offense since the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.

On 15 October 1945 Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occ ...

, the puppet leader of Nazi-occupied Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

, was executed for treason at Fresnes Prison in Paris.

On 11 March 1963 Jean Bastien-Thiry was the last person to be executed by firing squad for a failed attempt to assassinate French president Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

.

Indonesia

Execution by firing squad is the capital punishment method used in Indonesia. The following persons were executed (reported by BBC World Service) by firing squad on 29 April 2015 following convictions for drug offences: two Australians,Myuran Sukumaran

Myuran Sukumaran (17 April 1981 – 29 April 2015) was an Australian who was convicted in Indonesia of drug trafficking as a member of the Bali Nine. In 2005, Sukumaran was arrested in a room at the Melasti Hotel in Kuta with eight others. Pol ...

and Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan (; 12 January 1984 – 29 April 2015) was an Australian man who was convicted and executed in Indonesia for drug trafficking as a member of the Bali Nine. In 2005, Chan was arrested at Ngurah Rai International Airport in Denpasar. ...

, the Ghanaian Martin Anderson, the Indonesian Zainal Abidin bin Mgs Mahmud Badarudin, three Nigerians: Raheem Agbaje Salami, Sylvester Obiekwe Nwolise and Okwudili Oyatanze, as well as Brazilian Rodrigo Gularte

Rodrigo Muxfeldt Gularte (13 July 1972 – 29 April 2015) was a Brazilian citizen who was executed in Indonesia by firing squad for drug trafficking.

Gularte was diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. According to news reports, he did ...

.

In 2006 Fabianus Tibo

Fabianus Tibo was an Indonesian Catholic citizen who was executed by firing squad on 22 September 2006 at 1:20 a.m. local time together with Dominggus da Silva and Marinus Riwu for leading Poso riots, in 2000 that led to the murders of about ...

, Dominggus da Silva and Marinus Riwu

Marinus may refer to:

*Marinus (crater), a crater on the Moon

*Marinus (given name), for people named Marinus

*Dr. Marinus, a recurring character in the novels of David Mitchell

See also

*''The Keys of Marinus

''The Keys of Marinus'' is the ...

were executed. Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

n drug smugglers Samuel Iwachekwu Okoye and Hansen Anthoni Nwaolisa were executed in June 2008 in Nusakambangan

Nusa Kambangan (also Nusakambangan, Kambangan island, or Nusa Kambangan Island) island is located in Indonesia, separated by a narrow strait from the south coast of Java; the closest port is Cilacap in Central Java province. It known as the place ...

Island. Five months later three men convicted for the 2002 Bali bombing

The 2002 Bali bombings occurred on 12 October 2002 in the tourist district of Kuta on the Indonesian island of Bali. The attack killed 202 people (including 88 Australians, 38 Indonesians, 23 Britons, and people of more than 20 other nationa ...

— Amrozi, Imam Samudra

Imam Samudra ( ar, الإمام سامودرة, al-Imām Sāmūdirah, 14 January 1970 – 9 November 2008), also known as Abdul Aziz, Qudama/Kudama, Fatih/Fat, Abu Umar or Heri, was an Indonesian terrorist who was convicted and executed for his r ...

and Ali Ghufron

Huda bin Abdul Haq ( ar, هدى بن عبد الحق, Hudā bin ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq, also known as Ali Ghufron, Muklas or Mukhlas; February 1960 – 9 November 2008) was an Indonesian terrorist who was convicted and executed for his role in coordinat ...

—were executed on the same spot in Nusakambangan. In January 2013 56-year-old British woman Lindsay Sandiford

Lindsay June Sandiford (born 25 June 1956) is a former legal secretary and convicted drug smuggler from Redcar, Teesside in North Yorkshire, England who was sentenced to death in January 2013 by a court in Indonesia after being found guilty of sm ...

was sentenced to execution by firing squad for importing a large amount of cocaine; she lost her appeal against her sentence in April 2013. On 18 January 2015, under the new leadership of Joko Widodo

Joko Widodo (; born 21 June 1961), popularly known as Jokowi, is an Indonesian politician and businessman who is the 7th and current president of Indonesia. Elected in July 2014, he was the first Indonesian president not to come from an elit ...

, six people sentenced to death for producing and smuggling drugs into Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

were executed at Nusa Kambangan Penitentiary shortly after midnight.

Ireland

Following the 1916Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

in Ireland, 15 of the 16 leaders who were executed were shot by British military authorities under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

. The executions have often been cited as a reason for how the Rising managed to galvanise public support in Ireland after the failed rebellion.

Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

, a split in the government and the Dail led to a Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

during which the Free State Government sanctioned the executions by firing squad of 81 persons. Included in those numbers were some prominent prisoners who were executed without trial as reprisals.

Italy

Italy had used the firing squad as its only form of death penalty, both for civilians and military, since the unification of the country in 1861. The death penalty was abolished completely by both Italian Houses of Parliament in 1889 but revived under the Italiandictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

in 1926. Mussolini was himself shot in the last days of World War Two.

On 1 December 1945 Anton Dostler

Anton Dostler (10 May 1891 – 1 December 1945) was a German army officer who fought in both World Wars. During World War II, he commanded several units as a General of the Infantry, primarily in Italy. After the Axis defeat, Dostler was execute ...

, the first German general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

to be tried for war crimes, was executed by a U.S. firing squad in Aversa

Aversa () is a city and '' comune'' in the Province of Caserta in Campania, southern Italy, about 24 km north of Naples. It is the centre of an agricultural district, the ''Agro Aversano'', producing wine and cheese (famous for the typical ...

after being found guilty by a U.S. military tribunal of ordering the killing of 15 U.S. prisoners of war in Italy during World War II.

The last execution took place on 4 March 1947, as Francesco La Barbera, Giovanni Puleo and Giovanni D'Ignoti, sentenced to death on multiple accounts of robbery and murder, faced the firing squad at the range of Basse di Stura, near Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

. Soon after the Constitution of the newly proclaimed Republic prohibited the death penalty except for some crimes, like high treason, during wartime; no one was sentenced to death after 1947. In 2007 the Constitution was amended to ban the death penalty altogether.

Malta

Firing squads were used during the periods ofFrench

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and British control in Malta. Ringleaders of rebellions were often shot dead by firing squad during the French period, with perhaps the most notable examples being Dun Mikiel Xerri and other patriots in 1799.

The British also used the practice briefly, and for the last time in 1813, when two men were shot separately outside the courthouse

A courthouse or court house is a building that is home to a local court of law and often the regional county government as well, although this is not the case in some larger cities. The term is common in North America. In most other English-spe ...

after being convicted of failing to report their infection of plague to the authorities.

Mexico

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as

During the Mexican Independence War, several Independentist generals (such as Miguel Hidalgo

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), more commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican Wa ...

and José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

) were executed by Spanish firing squads.Known history of the Mexican Revolution Also, Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico

Maximilian I (german: Ferdinand Maximilian Josef Maria von Habsburg-Lothringen, link=no, es, Fernando Maximiliano José María de Habsburgo-Lorena, link=no; 6 July 1832 – 19 June 1867) was an Austrian archduke who reigned as the only Emperor ...

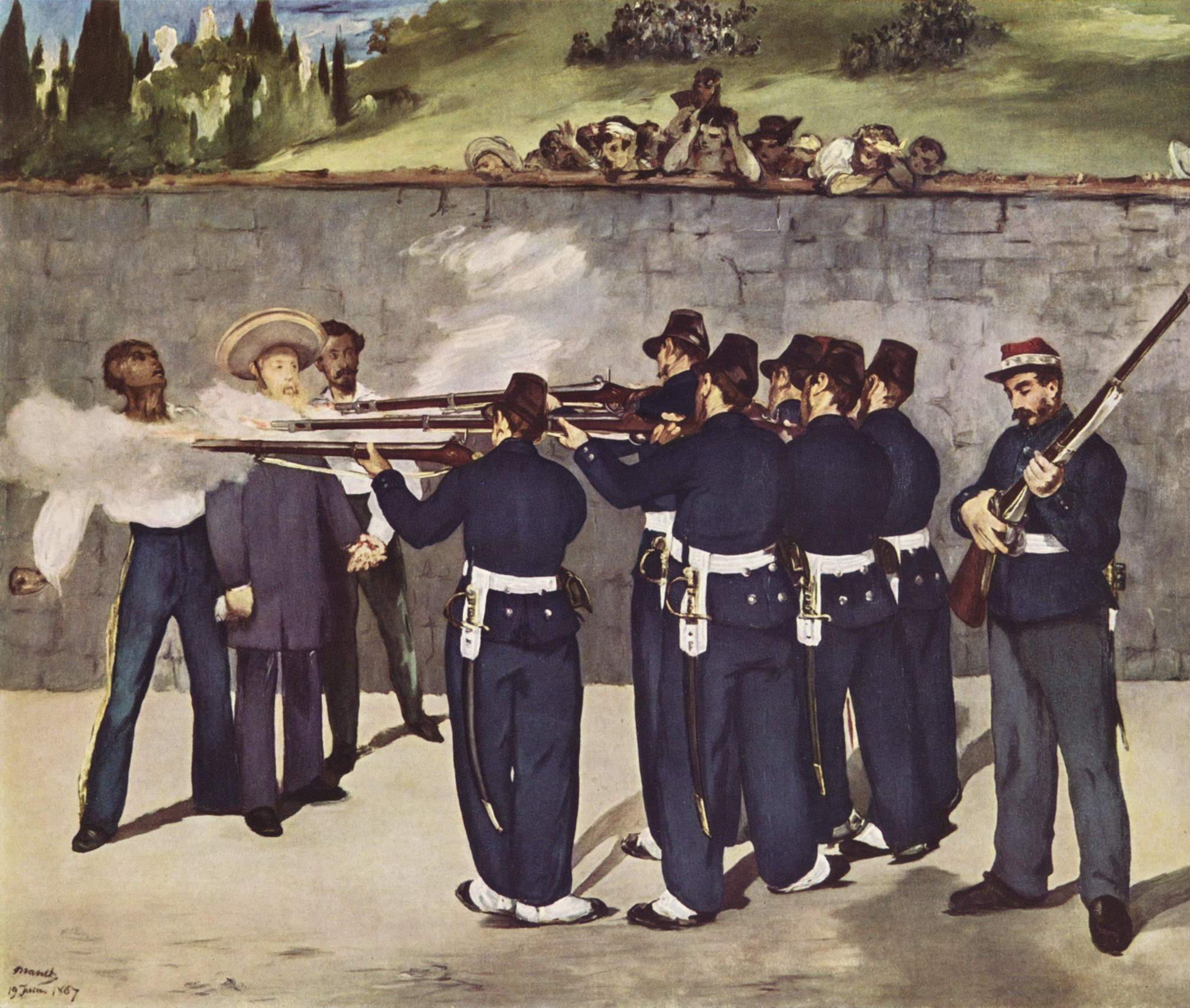

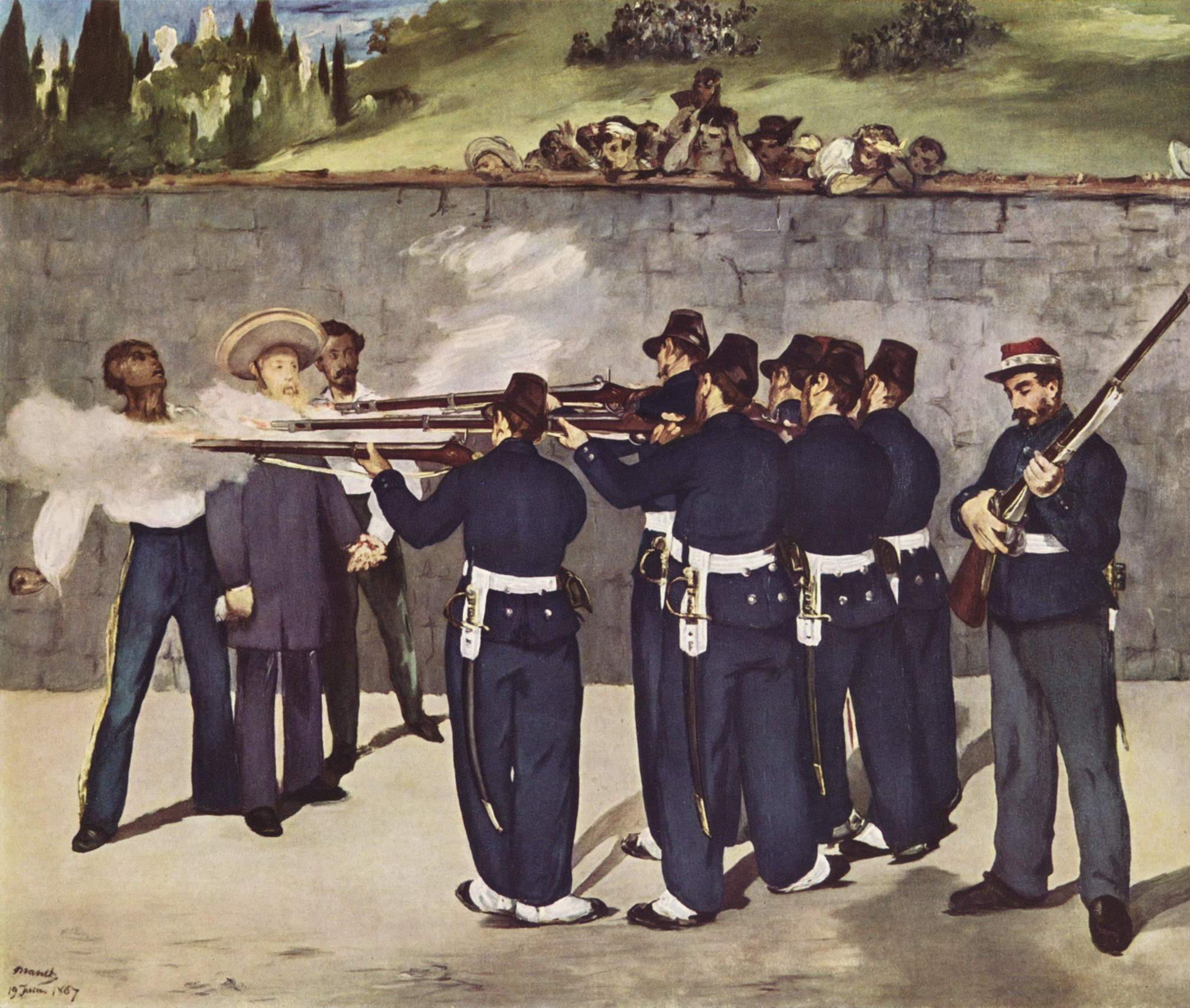

and two of his generals were executed in the Cerro de las Campanas after the Juaristas took control of Mexico in 1867. Manet

A wireless ad hoc network (WANET) or mobile ad hoc network (MANET) is a decentralized type of wireless network. The network is ad hoc because it does not rely on a pre-existing infrastructure, such as routers in wired networks or access points ...

immortalized the execution in a now-famous painting, '' The Execution of Emperor Maximilian''; he painted at least three versions.

Firing-squad execution was the most common way to carry out a death sentence in Mexico, especially during the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

and the Cristero War. An example of that is in the attempted execution of Wenseslao Moguel

Wenceslao Moguel Herrera (c. 1890 – 29 July 1976), known in the press as El Fusilado (''Spanish'': "The Executed One"), was a Mexican soldier under Pancho Villa who was captured on March 18, 1915 during the Mexican Revolution, and survived ex ...

, who survived being shot ten times—once at point-blank range—because he fought under Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

. After these events, the death sentence was imposed for fewer types of crimes in Article 22 of the Mexican Constitution

The Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States ( es, Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the current constitution of Mexico. It was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in ...

; however, in 1917 capital punishment was abolished completely.

Netherlands

During the Nazi occupation in World War II some 3,000 persons were executed by German firing squads. The victims were sometimes sentenced by a military court; in other cases they were hostages or arbitrary pedestrians who were executed publicly to intimidate the population. After the attack on high-ranking German officer Hanns Albin Rauter, about 300 people were executed publicly as reprisal against resistance movements. Rauter himself was executed nearScheveningen

Scheveningen is one of the eight districts of The Hague, Netherlands, as well as a subdistrict (''wijk'') of that city. Scheveningen is a modern seaside resort with a long, sandy beach, an esplanade, a pier, and a lighthouse. The beach is ...

on 12 January 1949, following his conviction for war crimes. Anton Mussert, a Dutch Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

leader, was sentenced to death by firing squad and executed in the dunes near The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

on 7 May 1946.

While under Allied guard in Amsterdam, and five days after the capitulation of Nazi Germany, two German Navy deserters were shot by a firing squad composed of other German prisoners kept in the Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

-run prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

. The men were lined up against the wall of an air raid shelter

Air raid shelters are structures for the protection of non-combatants as well as combatants against enemy attacks from the air. They are similar to bunkers in many regards, although they are not designed to defend against ground attack (but man ...

near an abandoned Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. The company sells automobi ...

assembly plant in the presence of Canadian military.

Nigeria

Nigeria executes criminals who committed armed robberies—such as Ishola Oyenusi,Lawrence Anini

Lawrence Nomanyakpon Anini (c. 1960 – March 29, 1987) was a Nigerian bandit who terrorised Benin City in the 1980s along with his sidekick Monday Osunbor. He was captured and executed for his crimes.

Arrest

On December 3, 1986, he was caug ...

and Osisikankwu Obioma Nwankwo predominantly known as Osiskankwu was a Nigerian kidnapper and murderer. He terrorised Abia state from 2008 until he was apprehended by the Joint Military Task Force of the Nigerian army

The Nigerian Army (NA) is the land force ...

—as well as military officers convicted of plotting coups against the government, such as Buka Suka Dimka

Lieutenant Colonel Bukar Suwa Dimka (1940 – 15 May 1976) was a Nigerian Army officer who played a leading role in the 13 February 1976 abortive military coup against the government of General Murtala Ramat Muhammed. Dimka also participated in t ...

and Maj. Gideon Orkar, by firing squad.

Norway

Vidkun Quisling, the leader of the collaborationist Nasjonal Samling Party and president of Norway during the German occupation in World War II, was sentenced to death fortreason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and executed by firing squad on 24 October 1945 at the Akershus Fortress.

Philippines

Jose Rizal

Jose is the English transliteration of the Hebrew and Aramaic name ''Yose'', which is etymologically linked to ''Yosef'' or Joseph. The name was popular during the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods.

*Jose ben Abin

*Jose ben Akabya

* Jose the Ga ...

was executed by firing squad on the morning of 30 December 1896, in what is now Rizal Park

Rizal Park ( fil, Liwasang Rizal, es, link=no, Parque Rizal), also known as Luneta Park or simply Luneta, is a historic urban park located in Ermita, Manila. It is considered one of the largest urban parks in the Philippines, covering an are ...

, where his remains have since been placed.

During the Marcos administration, drug trafficking was punishable by firing-squad execution, as was done to Lim Seng. Execution by firing squad was later replaced by the electric chair, then lethal injection

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person (typically a barbiturate, paralytic, and potassium solution) for the express purpose of causing rapid death. The main application for this procedure is capital puni ...

. On 24 June 2006, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo

Maria Gloria Macaraeg Macapagal Arroyo (, born April 5, 1947), often referred to by her initials GMA, is a Filipino academic and politician serving as one of the House Deputy Speakers since 2022, and previously from 2016 to 2017. She previously ...

abolished capital punishment through the enactment of Republic Act No. 9346. Existing death row

Death row, also known as condemned row, is a place in a prison that houses inmates awaiting execution after being convicted of a capital crime and sentenced to death. The term is also used figuratively to describe the state of awaiting execution ...

inmates, who numbered in the thousands, were eventually given life sentence

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes ...

s or reclusion perpetua

A recluse is a person who lives in voluntary seclusion from the public and society. The word is from the Latin ''recludere'', which means "shut up" or "sequester". Historically, the word referred to a Christian hermit's total isolation from th ...

instead.

Romania

Nicolae Ceaușescu

Nicolae Ceaușescu ( , ; – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist politician and dictator. He was the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and the second and last Communist leader of Romania. He ...

was executed by firing squad alongside his wife while singing the Communist Internationale following a show trial, bringing an end to the Romanian Revolution

The Romanian Revolution ( ro, Revoluția Română), also known as the Christmas Revolution ( ro, Revoluția de Crăciun), was a period of violent civil unrest in Romania during December 1989 as a part of the Revolutions of 1989 that occurred ...

, on Christmas Day, 1989.

Russia/USSR

In Imperial Russia, firing squads were used in the army for executions during combat on the orders of military tribunals. In the Soviet Union, from the very earliest days, the bullet to the back of the head, in front of a ready-dug burial trench was by far the most common practice. It became especially widely used during theGreat Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

.

Saudi Arabia

Executions in Saudi Arabia are usually carried out bybeheading

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

; however, at times other methods have been used. Al-Beshi, a Saudi executioner, has said that he has conducted some executions by shooting. Mishaal bint Fahd bin Mohammed Al Saud

Mishaal bint Fahd Al Saud (1958 – 15 July 1977; ar, الأميرة مشاعل بنت فهد بن محمد بن عبدالعزيز آل سعود) was a member of the House of Saud who was executed by shooting for committing adultery in 197 ...

, a Saudi princess, was also executed in the same way.

South Africa

Australian soldiers Harry "Breaker" Morant and Peter Handcock were executed by a British firing squad in theSouth African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

on 27 February 1902 for war crimes during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

.

United Arab Emirates

In theUnited Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia (Middle East, The Middle East). It is ...

, firing squad is the preferred method of execution.

United Kingdom

The standard method of execution in the United Kingdom washanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

. Execution by firing squad was limited to times of war, armed insurrection and in the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, although it is now outlawed in all circumstances, along with all other forms of capital punishment. The

The Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

was used during both World Wars for executions. During World War I, eleven captured German spies were shot between 1914 and 1916: nine on the Tower's rifle range and two in the Tower Ditch, all of whom were buried in East London Cemetery

The East London Cemetery and Crematorium are located in West Ham in the London Borough of Newham. It is owned and operated by the Dignity Funeral Group.

History

The cemetery was founded in 1871 and laid out in 1872 to meet the increasing deman ...

, in Plaistow, London. On 15 August 1941, the last execution at the Tower was that of German Cpl. Josef Jakobs

Josef Jakobs (30 June 1898 – 15 August 1941) was a German spy and the last person to be executed at the Tower of London. He was captured shortly after parachuting into the United Kingdom during the Second World War. Convicted of espionage unde ...

, shot for espionage during World War II.

The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

took over Shepton Mallet prison in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

in 1942, renaming it Disciplinary Training Center No.1 and housing troops convicted of offences across Europe. There were eighteen executions at the prison, two of them by firing squad for murder: Pvt. Alexander Miranda on 30 May 1944 and Pvt. Benjamin Pygate on 28 November 1944. Locals complained about the noise, as the executions took place in the prison yard at 1:00am.

Since the 1960s, there has been some controversy concerning the 346 British and Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas

...

troops—including 25 Canadians, 22 Irish and 5 New Zealanders—shot for desertion, murder, cowardice and other offences during World War I, some of whom are now thought to have been suffering from combat stress reaction

Combat stress reaction (CSR) is acute behavioral disorganization as a direct result of the trauma of war. Also known as "combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", or "battle neurosis", it has some overlap with the diagnosis of acute stress reaction used ...

or post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats o ...

("shell-shock", as it was then known). This led to organisations such as the Shot at Dawn Campaign being set up in later years to try to uncover just why these soldiers were executed. The Shot at Dawn Memorial

The Shot at Dawn Memorial is a monument at the National Memorial Arboretum near Alrewas, in Staffordshire, UK. It commemorates the 306 British Army and Commonwealth soldiers executed after courts-martial for desertion and other capital offences ...

was erected at Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands C ...

to honour these soldiers. In August 2006 it was announced that 306 of these soldiers would receive posthumous pardons.

United States

American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, General George Washington approved a sentence of death by firing squad, but the prisoner was later pardoned.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, 433 of the 573 men executed were shot dead by a firing squad: 186 of the 267 executed by the Union Army, and 247 of the 306 executed by the Confederate Army.

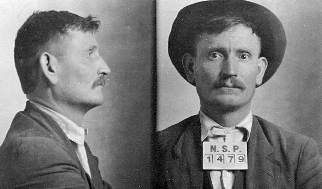

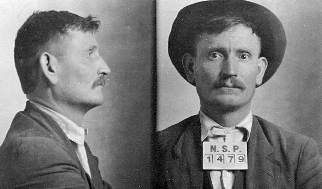

In 1913, Andriza Mircovich

Andriza (or Andrew) Mircovich ( sr, Андрија Мирковић / Andrija Mirković, 1879 – May 14, 1913) was an Austro-Hungarian national of Serb descent. He was the only prisoner ever to be executed by shooting in the US state of Ne ...

became the first and only inmate in Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

to be executed by shooting. After the warden of Nevada State Prison

Nevada State Prison (NSP) was a penitentiary located in Carson City. The prison was in continuous operation since its establishment in 1862 and was managed by the Nevada Department of Corrections. It was one of the oldest prisons still operatin ...

could not find five men to form a firing squad, a shooting machine was built to carry out Mircovich's execution.

John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the University of Utah School of Medicine, at his request.

Since 1960 there have been four executions by firing squad, all in

John W. Deering allowed an electrocardiogram recording of the effect of gunshot wounds on his heart during his 1938 execution by firing squad, and afterwards his body was donated to the University of Utah School of Medicine, at his request.

Since 1960 there have been four executions by firing squad, all in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

: The 1960 execution of James W. Rodgers

James W. Rodgers (August 3, 1910 – March 30, 1960) was an American who was sentenced to death by the state of Utah for the murder of miner Charles Merrifield in 1957. In his final statement before his execution by firing squad in 1960, Ro ...

, Gary Gilmore

Gary Mark Gilmore (born Faye Robert Coffman; December 4, 1940 – January 17, 1977) was an American criminal who gained international attention for demanding the implementation of his death sentence for two murders he had admitted to committing ...

's execution in 1977, and John Albert Taylor

John Albert Taylor (June 6, 1959 – January 26, 1996) was an American who was convicted of burglary and carrying a concealed weapon in the state of Florida, and sexual assault and murder in the state of Utah. Taylor's own sister tipped of ...

in 1996, who chose a firing squad for his execution, according to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', "to make a statement that Utah was sanctioning murder". However, a 2010 article for the British newspaper ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' quotes Taylor justifying his choice because he did not want to "flop around like a dying fish" during a lethal injection. Ronnie Lee Gardner

Ronnie Lee Gardner (January 16, 1961 – June 18, 2010) was an American criminal who received the death penalty for killing a man during an attempted escape from a courthouse in 1985, and was executed by a firing squad by the state of Utah in 20 ...

was executed by firing squad in 2010, having said he preferred this method of execution because of his "Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into se ...

heritage". Gardner also felt that lawmakers were trying to eliminate the firing squad, in opposition to popular opinion in Utah, because of concern over the state's image in the 2002 Winter Olympics

The 2002 Winter Olympics, officially the XIX Olympic Winter Games and commonly known as Salt Lake 2002 ( arp, Niico'ooowu' 2002; Gosiute Shoshoni: ''Tit'-so-pi 2002''; nv, Sooléí 2002; Shoshoni: ''Soónkahni 2002''), was an internationa ...

.

Execution by firing squad was banned in Utah in 2004, but as the ban was not retroactive, three inmates on Utah's death row

Death row, also known as condemned row, is a place in a prison that houses inmates awaiting execution after being convicted of a capital crime and sentenced to death. The term is also used figuratively to describe the state of awaiting execution ...

have the firing squad set as their method of execution. Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

banned execution by firing squad in 2009, temporarily leaving Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New ...

as the only state utilizing this method of execution (and only as a secondary method).

Reluctance by drug companies to see their drugs used to kill people has led to a shortage of the commonly used lethal injection drugs. In March 2015, Utah enacted legislation allowing for execution by firing squad if the drugs they use are unavailable. Several other states are also exploring a return to the firing squad. Thus, after waning in both use and popularity in recent decades, as of 2022, firing squad executions appear to be at least anecdotally regaining popularity as an alternative to lethal injection

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person (typically a barbiturate, paralytic, and potassium solution) for the express purpose of causing rapid death. The main application for this procedure is capital puni ...

.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor argued in ''Arthur v. Dunn'' (2017): "In addition to being near instant, death by shooting may also be comparatively painless. ..And historically, the firing squad has yielded significantly fewer botched executions."

On January 30, 2019, South Carolina's Senate voted 26–13 in favor of a revived proposal to bring back the electric chair and add firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are ...

s to its execution options. On May 14, 2021, South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster signed a bill into law which brought back the electric chair as the default method of execution (in the event lethal injection was unavailable) and added the firing squad to the list of execution options. South Carolina has not performed executions in over a decade, and its lethal injection drugs expired in 2013. Pharmaceutical companies have since refused to sell drugs for lethal injection.

On April 7, 2022, the South Carolina Supreme Court scheduled the execution of Richard Bernard Moore

Richard Bernard Moore (born February 20, 1965) is an American man on death row in South Carolina. He was convicted of the September 1999 murder of James Mahoney, a convenience store clerk, in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Moore's case received inte ...

for April 29, 2022. On April 15, 2022, Moore chose to be executed by firing squad instead of the electric chair, however, his execution was later stayed by the South Carolina Supreme Court.

See also

*Bullet fee

A bullet fee is a financial charge levied on the family of executed prisoners. Bullet fees have been levied in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Kingdom of Yugoslavia, as well as in the People's Republic of China, and Nazi Germanyhttp://karlrobertkreit ...

* Use of capital punishment by country

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is a state-sanctioned practice of killing a person as a punishment for a crime. Historically, capital punishment has been used in almost every part of the world. Currently, the large majorit ...

Notes and references

Further reading

* Moore, William, ''The Thin Yellow Line'', Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1974 * Putkowski and Sykes, ''Shot at Dawn'', Leo Cooper, 2006 * Hughs-Wilson, John and Corns, Cathryn M, ''Blindfold and Alone: British Military Executions in the Great War'', Cassell, 2005 * Johnson, David, ''Executed at Dawn: The British Firing Squads of the First World War'', History Press, 2015External links

Firing Squad Execution of a Civil War Deserter Described in an 1861 Newspaper

* ttp://www.thefirstpost.co.uk/64684,in-pictures,news-in-pictures,death-by-firing-squad Death by Firing Squadnbsp;– slideshow by '' The First Post''

Nazis Meet the Firing Squad

– slideshow by ''

Life magazine

''Life'' was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, ''Life'' was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest ma ...

''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Execution By Firing Squad

Firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are ...

Capital punishment