European witchcraft on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Belief in

Belief in

In

In

Similarly, the Lombard code of 643 states:

This conforms to the thoughts of Saint Augustine of Hippo, who taught that witchcraft did not exist and that the belief in it was heretical.

In 814,

Similarly, the Lombard code of 643 states:

This conforms to the thoughts of Saint Augustine of Hippo, who taught that witchcraft did not exist and that the belief in it was heretical.

In 814,  The

The

In England,

In England,

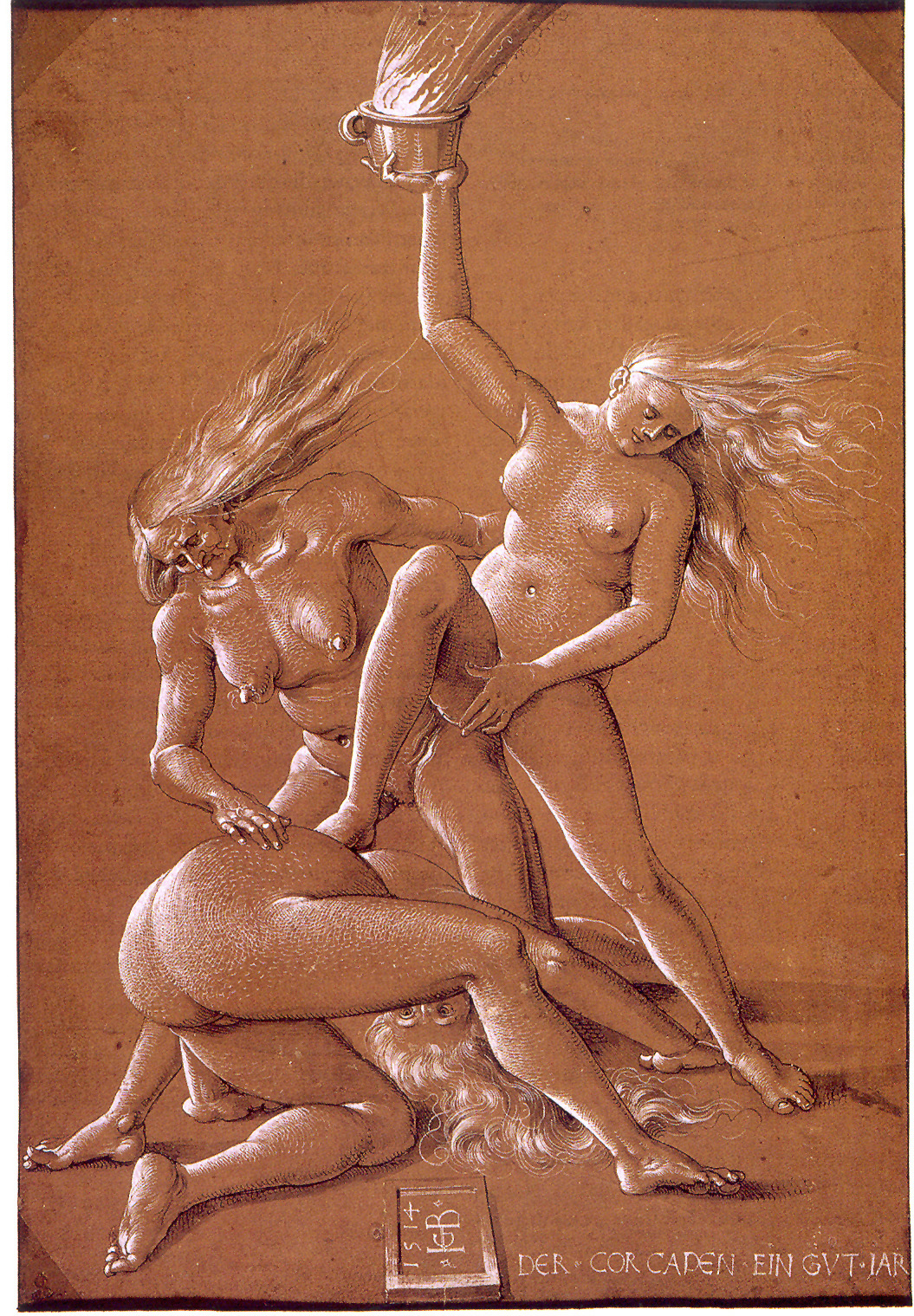

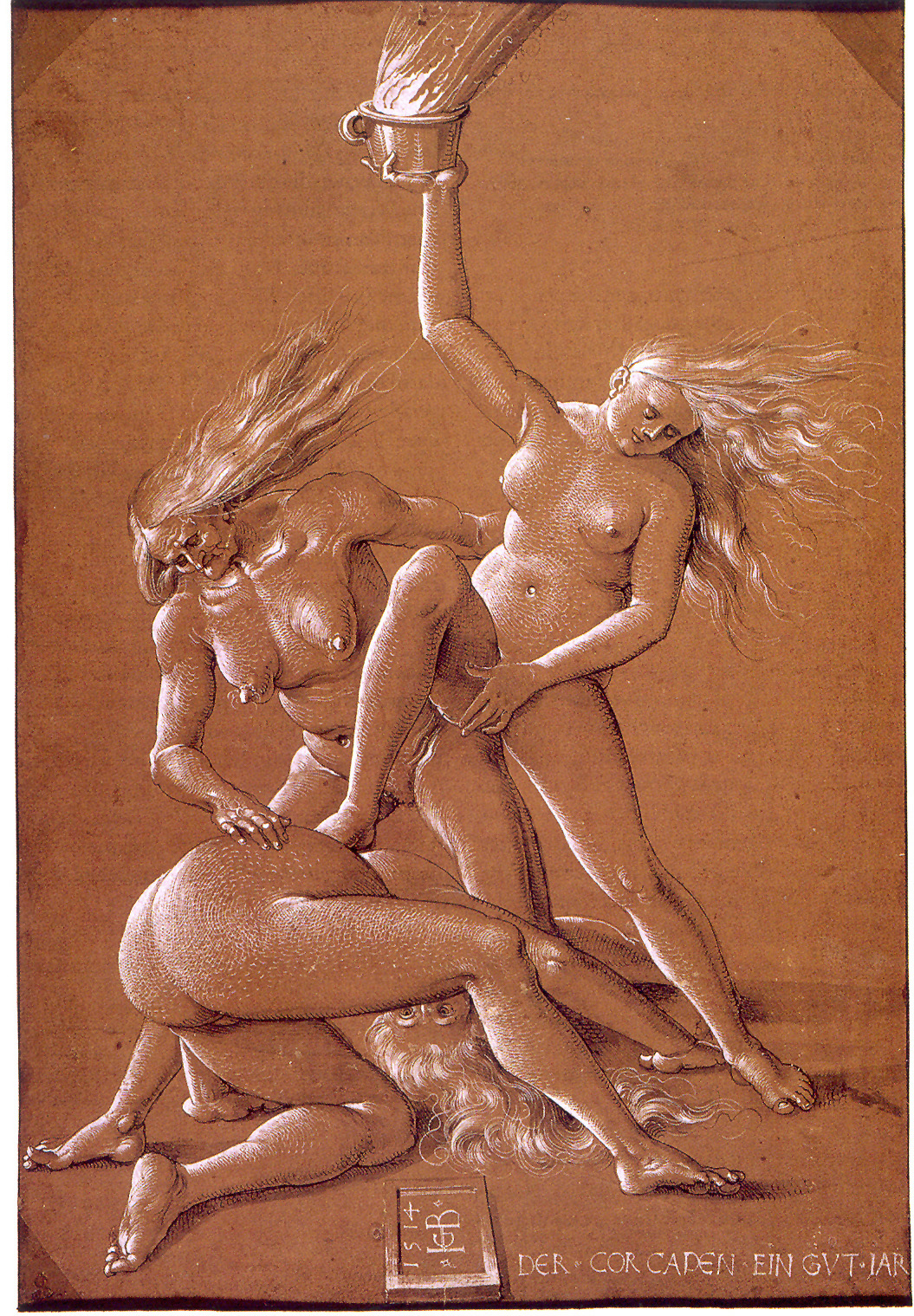

The characterization of the witch in Europe is not derived from a single source.

The familiar witch of folklore and popular superstition is a combination of numerous influences.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the recurring beliefs about witches were:

The ''

The characterization of the witch in Europe is not derived from a single source.

The familiar witch of folklore and popular superstition is a combination of numerous influences.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the recurring beliefs about witches were:

The '' Especially in media aimed at children (such as

Especially in media aimed at children (such as

in JSTOR

* . * Scarre, Geoffrey, and John Callow. ''Witchcraft and magic in sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Europe'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001). * Waite, Gary K. ''Heresy, Magic and Witchcraft in early modern Europe'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003). {{Witchcraft European witchcraft

Belief in

Belief in witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

can be traced to classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

and has continuous history during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, culminating in the Early Modern witch trials and giving rise to the fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful beings. In most cult ...

and popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

"witch" stock character of modern times, as well as to the concept of the "modern witch" in Wicca

Wicca () is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religion categorise it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and w ...

and related movements of contemporary witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have use ...

.

In medieval and early modern Europe, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have used magic to cause harm and misfortune to members of their own community. Witchcraft was seen as immoral and often thought to involve communion with evil beings, such as a "Deal with the Devil

A deal with the Devil (also called a Faustian bargain or Mephistophelian bargain) is a cultural motif exemplified by the legend of Faust and the figure of Mephistopheles, as well as being elemental to many Christian traditions. According to ...

". It was believed witchcraft could be thwarted by protective magic or counter-magic, which could be provided by the cunning folk

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services a ...

. Suspected witches were also intimidated, banished, attacked or lynched. Often they would be formally prosecuted and punished if found guilty. European witch-hunt

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern pe ...

s and witch trials in the early modern period

Witch trials in the early modern period saw that between 1400 to 1782, around 40,000 to 60,000 were killed due to suspicion that they were practicing witchcraft. Some sources estimate that a total of 100,000 trials occurred at its maximum for a s ...

led to tens of thousands of executions - almost always of women who did not practice witchcraft. European belief in witchcraft gradually dwindled during and after the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

The topic is a complex amalgamation of the practices of folk healer

A folk healer is an unlicensed person who practices the art of healing using traditional practices, herbal remedies and the power of suggestion.

The healer may be a highly trained person who pursues their specialties, learning by study, observa ...

s, folk magic, ancient belief in sorcery

Sorcery may refer to:

* Magic (supernatural), the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed to subdue or manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces

** Witchcraft, the practice of magical skills and abilities

* Magic in fiction, ...

in pagan Europe, Christian views on heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

, medieval and early modern practice of ceremonial magic and simple fiction in folklore and literature.

History

Antiquity

Instances of persecution of witchcraft in the classical period were documented, paralleling evidence from theancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

and the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

. In ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

, for example, Theoris, a woman of Lemnos, was prosecuted for casting incantations and using harmful drugs. She was executed along with her family.

In

In Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom ...

black magic was punished as a capital offence by the Law of the Twelve Tables

The Laws of the Twelve Tables was the legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. Formally promulgated in 449 BC, the Tables consolidated earlier traditions into an enduring set of laws.Crawford, M.H. 'Twelve Tables' in Simon Hornblow ...

, which are to be assigned to the 5th century BC, and, as Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

records, from time to time Draconian statutes were directed against those who attempted to blight crops and vineyards or to spread disease among flocks and cattle. The terms of the frequent references in Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

to Canidia illustrate the odium in which sorceresses were held. Under the Empire, in the third century, the punishment of burning alive was enacted by the State against witches who compassed another person's death through their enchantments. Nevertheless, all the while normal legislation utterly condemned witchcraft and its works, while the laws were not merely carried out to their very letter, but reinforced by such emperors as Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Drusus and Antonia Minor ...

, Vitellius

Aulus Vitellius (; ; 24 September 1520 December 69) was Roman emperor for eight months, from 19 April to 20 December AD 69. Vitellius was proclaimed emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of ci ...

, and Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Emp ...

.

In the imperial period, it is evident from many Latin authors and from the historians that Rome swarmed with occultists and diviners, many of whom in spite of the Lex Cornelia almost openly traded in poisons, and not infrequently in assassination to boot. Paradoxical as it may appear, such emperors as Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

, and Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary suc ...

, while banishing from their realms all seers and necromancers, and putting them to death, in private entertained astrologers and wizards among their retinue, consulting their art upon each important occasion, and often even in the everyday and ordinary affairs of life. These prosecutions are significant, as they establish that and the prohibition under severest penalties, the sentence of death itself of witchcraft was demonstrably not a product of Christianity, but had long been employed among polytheistic societies.

The ecclesiastical legislation followed a similar but milder course. The Council of Elvira (306), Canon 6, refused the holy Viaticum to those who had killed a man by a "per maleficium", translated as "visible effect of malicious intention" and adds the reason that such a crime could not be effected "without idolatry"; which probably means without the aid of the Devil, devil-worship and idolatry being then convertible terms. Similarly canon 24 of the Council of Ancyra (314) imposes five years of penance upon those who consult magicians, and here again the offence is treated as being a practical participation in paganism. This legislation represented the mind of the Church for many centuries. Similar penalties were enacted at the Eastern council in Trullo (692), while certain early Irish canons in the far West treated sorcery as a crime to be visited with excommunication until adequate penance had been performed.

The early legal codes of most European nations contain laws directed against witchcraft. Thus, for example, the oldest document of Frankish legislation, the Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; la, Lex salica), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by the first Frankish King, Clovis. The written text is in Latin and contains some of the earliest known instances of Old D ...

, which was reduced to a written form and promulgated under Clovis, who died 27 November, 511, punishes those who practice magic with various fines, especially when it could be proven that the accused launched a deadly curse, or had tied the Witch's Knot. The laws of the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

, which were to some extent founded upon the Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

, punished witches who had killed any person by their spells with death; while long-continued and obstinate witchcraft, if fully proven, was visited with such severe sentences as slavery for life.

Christianization and Early Middle Ages

The '' Pactus Legis Alamannorum'', an early 7th-century code of laws of theAlemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

confederation of Germanic tribes, lists witchcraft as a punishable crime on equal terms with poisoning. If a free man accuses a free woman of witchcraft or poisoning, the accused may be disculpated either by twelve people swearing an oath on her innocence or by one of her relatives defending her in a trial by combat

Trial by combat (also wager of battle, trial by battle or judicial duel) was a method of Germanic law to settle accusations in the absence of witnesses or a confession in which two parties in dispute fought in single combat; the winner of the ...

. In this case, the accuser is required to pay a fine (''Pactus Legis Alamannorum'' 13). Charles the Great prescribed the death penalty for anyone who would burn witches.

With Christianization, belief in witchcraft came to be seen as superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs ...

. The Council of Leptinnes in 744 drew up a "List of Superstitions", which prohibited sacrifice to saints and created a baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

al formula that required one to renounce works of demons, specifically naming Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, ...

and Odin

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, ...

. Persecution of witchcraft nevertheless persisted throughout most of the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, into the 10th century.

When Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

imposed Christianity upon the people of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a ...

in 789, he proclaimed:

Similarly, the Lombard code of 643 states:

This conforms to the thoughts of Saint Augustine of Hippo, who taught that witchcraft did not exist and that the belief in it was heretical.

In 814,

Similarly, the Lombard code of 643 states:

This conforms to the thoughts of Saint Augustine of Hippo, who taught that witchcraft did not exist and that the belief in it was heretical.

In 814, Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (german: Ludwig der Fromme; french: Louis le Pieux; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aqu ...

upon his accession to the throne began to take very active measures against all sorcerers and necromancers, and it was owing to his influence and authority that the Council of Paris in 829 appealed to the secular courts to carry out any such sentences as the Bishops might pronounce. The consequence was that from this time forward the penalty of witchcraft was death, and there is evidence that if the constituted authority, either ecclesiastical or civil, seemed to slacken in their efforts the populace took the law into their own hands with far more fearful results.

In England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, the early Penitentials are greatly concerned with the repression of pagan ceremonies, which under the cover of Christian festivities were very largely practised at Christmas and on New Year's Day. These rites were closely connected with witchcraft, and especially do S. Theodore, S. Aldhelm, Ecgberht of York, and other prelates prohibit the masquerade as a horned animal, a stag, or a bull, which S. Caesarius of Arles had denounced as a ''"foul tradition,"'' an ''"evil custom,"'' a ''"most heinous abomination."'' The laws of King Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his fir ...

(924–40), corresponsive with the early French laws, punished any person casting a spell which resulted in death by extracting the extreme penalty.

Among the laws attributed to the Pictish King Cináed mac Ailpin (ruled 843 to 858), ''"is an important statute which enacts that all sorcerers and witches, and such as invoke spirits, "and use to seek upon them for helpe, let them be burned to death". Even then this was obviously no new penalty, but the statutory confirmation of a long-established punishment. So the witches of Forres who attempted the life of King Duffus in the year 968 by the old bane of slowly melting a wax image, when discovered, were according to the law burned at the stake."''

The

The Canon Episcopi

The title canon ''Episcopi'' (or ''capitulum Episcopi'') is conventionally given to a certain passage found in medieval canon law.

The text possibly originates in an early 10th-century penitential, recorded by Regino of Prüm; it was included ...

, which was written circa 900 AD (though alleged to date from 314 AD), once more following the teachings of Saint Augustine, declared that witches did not exist and that anyone who believed in them was a heretic. The crucial passage from the Canon Episcopi reads as follows:

Early modern witch hunts

The origins of the accusations against witches in the Early Modern period are eventually present in trials against heretics, which trials include claims of secret meetings, orgies, and the consumption of babies. From the 15th century, the idea of a pact became important—one could be possessed by the Devil and not responsible for one's actions, but to be a witch, one had to sign a pact with the Devil, often to worship him, which was heresy and meant damnation. The idea of an explicit and ceremonial pact with the Devil was crucial to the development of the witchcraft concept, because it provided an explanation that differentiated the figure of the witch from that of the learned necromancer or sorcerer (whose magic was presumed to be diabolic in source, but with the power to wield it being achieved through rigorous application of study and complex ritual). A rise in the practice of necromancy in the 12th century, spurred on by an influx of texts on magic and diabolism from the Islamic world, had alerted clerical authorities to the potential dangers of malefic magic. This elevated concern was slowly expanded to include the common witch, but clerics needed an explanation for why uneducated commoners could perform feats of diabolical sorcery that rivaled those of the most seasoned and learned necromancers. The idea that witches gained their powers through a pact with the Devil provided a satisfactory explanation, and allowed authorities to develop a mythology through which they could project accusations of crimes formerly associated with various heretical sects (incestuous orgies, cannibalism, ritualinfanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of resou ...

, and the worship of demonic familiars) onto the newly emerging threat of diabolical witchcraft. This pact and the ceremony that accompanied it became widely known as the witches' sabbath

A Witches' Sabbath is a purported gathering of those believed to practice witchcraft and other rituals. The phrase became popular in the 20th century.

Origins

In 1668, Johannes Praetorius published his literary work "Blockes-Berges Verrichtu ...

.

By 1300, the elements were in place for a witch hunt, and for the next century and a half, fear of witches spread gradually throughout Europe. At the end of the Middle Ages (about 1450), the fear became a craze that lasted more than 200 years. As the notion spread that all magic involved a pact with the Devil, legal sanctions against witchcraft grew harsher. Each new conviction reinforced the beliefs in the methods (torture and pointed interrogation) being used to solicit confessions and in the list of accusations to which these "witches" confessed. The rise of the witch-craze was concurrent with the rise of Renaissance magic

Renaissance magic was a resurgence in Hermeticism and Neo-Platonic varieties of the magical arts which arose along with Renaissance humanism in the 15th and 16th centuries CE. These magical arts (called '' artes magicae'') were divided into sev ...

in the great humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

of the time (this was called High Magic, and the Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

s and Aristotelians that practised it took pains to insist that it was wise and benevolent and nothing like Witchcraft), which helped abet the rise of the craze. Witchcraft was held to be the worst of heresies, and early skepticism slowly faded from view almost entirely.

In the early 14th century, many accusations were brought against clergymen and other learned people who were capable of reading and writing magic; Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani family was of baronial ...

(d. 1303) was posthumously tried for apostasy, murder, and sodomy, in addition to allegedly entering into a pact with the Devil (while popes had been accused of crimes before, the demonolatry charge was new). The Templars were also tried as Devil-invoking heretics in 1305–14. The middle years of the 14th century were quieter, but towards the end of the century, accusations increased and were brought against ordinary people more frequently. In 1398, the University of Paris declared that the demonic pact could be implicit; no document need be signed, as the mere act of summoning a demon constituted an implied pact. Tens of thousands of trials continued through Europe generation after generation; William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

wrote about the infamous "Three Witches

The Three Witches, also known as the Weird Sisters or Wayward Sisters, are characters in William Shakespeare's play ''Macbeth'' (c. 1603–1607). The witches eventually lead Macbeth to his demise, and they hold a striking resemblance to the ...

" in his tragedy ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' during the reign of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, who was notorious for his ruthless prosecution of witchcraft.

Accusations against witches were almost identical to those levelled by 3rd-century pagans against early Christians:

The craze took on new strength in the 15th century, and in 1486, Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer ( 1430 – 1505, aged 74-75), also known under the Latinized name Henricus Institor, was a German churchman and inquisitor. With his widely distributed book ''Malleus Maleficarum'' (1487), which describes witchcraft and endors ...

, a member of the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

, published the ''Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and first ...

'' (the 'Hammer against the Witches'). This book was banned by the Church in 1490 and scholars are unclear on just how influential the Malleus was in its day. Less than one hundred years after it was written, the Council of the Inquisitor General in Spain discounted the credibility of the Malleus since it contained numerous errors.

Persecution continued through the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, and the Protestants and Catholics both continued witch trials with varying numbers of executions from one period to the next. The "Caroline Code", the basic law code of the Holy Roman Empire (1532) imposed heavy penalties on witchcraft. As society became more literate (due mostly to the invention of the printing press in the 1440s), increasing numbers of books and tracts fueled the witch fears.

The craze reached its height between 1560 and 1660. After 1580, the Jesuits replaced the Dominicans as the chief Catholic witch-hunters, and the Catholic Rudolf II (1576–1612) presided over a long persecution in Austria. The Jura Mountains in southern Germany provided a small respite from the insanity; there, torture was imposed only within the precise limits of the Caroline Code of 1532, little attention was paid to the accusations of or by children, and charges had to be brought openly before a suspect could be arrested. These limitations contained the mania in that area.

The nuns of Loudun

Loudun (; ; Poitevin: ''Loudin'') is a commune in the Vienne department and the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, western France.

It is located south of the town of Chinon and 25 km to the east of the town Thouars. The area south of Loudun i ...

(1630), novelized by Aldous Huxley and made into a film by Ken Russell

Henry Kenneth Alfred Russell (3 July 1927 – 27 November 2011) was a British film director, known for his pioneering work in television and film and for his flamboyant and controversial style. His films in the main were liberal adaptation ...

, provide an example of the craze during this time. The nuns had conspired to accuse Father Urbain Grandier of witchcraft by faking symptoms of possession and torment; they feigned convulsions, rolled and gibbered on the ground, and accused Grandier of indecencies. Grandier was convicted and burned; however, after the plot succeeded, the symptoms of the nuns only grew worse, and they became more and more sexual in nature. This attests to the degree of mania and insanity present in such witch trials.

In 1687, Louis XIV issued an edict against witchcraft that was rather moderate compared to former ones; it ignored black cats and other lurid fantasies of the witch mania. After 1700, the number of witches accused and condemned fell rapidly.

Witchcraft in Britain

In England,

In England, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

, and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

there was a succession of Witchcraft Acts

In England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, and the British colonies, there has historically been a succession of Witchcraft Acts governing witchcraft and providing penalties for its practice, or—in later years—rather for pretending to practise ...

starting with Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

's Act of 1542. They governed witchcraft and providing penalties for its practice, or—after 1700—rather for pretending to practise it.

In Wales, witchcraft trials heightened in the 16th and 17th centuries, after the fear of it was imported from England. There was a growing alarm of women's magic as a weapon aimed against the state and church. The Church made greater efforts to enforce the canon law of marriage, especially in Wales where tradition allowed a wider range of sexual partnerships. There was a political dimension as well, as accusations of witchcraft were levied against the enemies of Henry VII, who was exerting more and more control over Wales.

The records of the Courts of Great Sessions for Wales, 1536–1736 show that Welsh custom was more important than English law. Custom provided a framework of responding to witches and witchcraft in such a way that interpersonal and communal harmony was maintained, Showing to regard to the importance of honour, social place and cultural status. Even when found guilty, execution did not occur.

Becoming king in 1603, James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

brought to England and Scotland continental explanations of witchcraft. He set out the much stiffer Witchcraft Act of 1604, which made it a felony under common law. One goal was to divert suspicion away from male homosociality among the elite, and focus fear on female communities and large gatherings of women. He thought they threatened his political power so he laid the foundation for witchcraft and occultism policies, especially in Scotland. The point was that a widespread belief in the conspiracy of witches and a witches' Sabbath with the devil deprived women of political influence. Occult power was supposedly a womanly trait because women were weaker and more susceptible to the devil.

Enlightenment attitudes after 1700 made a mockery of beliefs in witches. The Witchcraft Act of 1735

The Witchcraft Act 1735 (9 Geo. 2 c. 5) was an Act of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1735 which made it a crime for a person to claim that any human being had magical powers or was guilty of practising witchcraft. With this, t ...

marked a complete reversal in attitudes. Penalties for the practice of witchcraft as traditionally constituted, which by that time was considered by many influential figures to be an impossible crime, were replaced by penalties for the pretence of witchcraft. A person who claimed to have the power to call up spirits, or foretell the future, or cast spells, or discover the whereabouts of stolen goods, was to be punished as a vagrant and a con artist, subject to fines and imprisonment.

Hallucinogens and witchcraft

Arguments in favor

A number of modern researchers have argued for the existence of hallucinogenic plants in the practice of European witchcraft; among them, anthropologists Edward B. Taylor, Bernard Barnett, Michael J. Harner and Julio C. BarojaBaroja, Julio C., (1964) ''The World of the Witches''. University of Chicago Press. and pharmacologistsLouis Lewin

Louis Lewin (9 November 1850 - 1 December 1929) was a German pharmacologist. In 1887 he received his first sample of the Peyote cactus from Dallas, Texas-based physician John Raleigh Briggs (1851-1907), and later published the first methodical a ...

Lewin, Louis. (1964) ''Phantastica, Narcotic and Stimulating Drugs: Their Use and Abuse''. E.P. Dutton, New York. and Erich Hesse.Hesse, Erich. (1946) ''Narcotics and Drug Addiction''. Philosophical Library of New York. Many medieval writers also comment on the use of hallucinogenic plants in witches' ointments, including Joseph Glanvill

Joseph Glanvill (1636 – 4 November 1680) was an English writer, philosopher, and clergyman. Not himself a scientist, he has been called "the most skillful apologist of the virtuosi", or in other words the leading propagandist for the approa ...

,Glanvil, Joseph. 1681. ''Saducismus Triumphatus''. London Jordanes de Bergamo, Sieur de Beauvoys de Chauvincourt, Martin Delrio, Raphael Holinshed

Raphael Holinshed ( – before 24 April 1582) was an English chronicler, who was most famous for his work on ''The Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande'', commonly known as ''Holinshed's Chronicles''. It was the "first complete printe ...

, Andrés Laguna, Johannes Nider

Johannes Nider (c. 1380 – 13 August 1438) was a German theologian.

__NOTOC__ Life

Nider was born in Swabia. He entered the Order of Preachers at Colmar and after profession was sent to Vienna for his philosophical studies, which he finished ...

, Sieur Jean de Nynald, Henry Boguet

Henry Boguet (1550 in Pierrecourt, Haute-Saône – 1619) was a well known jurist and judge of Saint-Claude (1596–1616) in the County of Burgundy. His renown is to a large degree based on his fame as a demonologist for his ''Discours ex ...

, Giovanni Porta, Nicholas Rémy, Bartolommeo Spina, Richard Verstegan

Richard Rowlands, born Richard Verstegan (c. 1550 – 1640), was an Anglo- Dutch antiquary, publisher, humorist and translator. Verstegan was born in East London the son of a cooper; his grandfather, Theodore Roland Verstegen, was a refugee f ...

, Johann Vincent and Pedro Ciruelo.Harner, Michael J., ed. (1973) "The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft" in ''Hallucinogens and Shamanism''. Oxford University Press. Library of Congress: 72-92292. p. 128–50

Much of the knowledge of herbalism

Herbal medicine (also herbalism) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. With worldwide research into pharmacology, some herbal medicines have been translated into modern reme ...

in European witchcraft comes from the Spanish Inquisitors and other authorities, who occasionally recognized the psychological nature of the "witches' flight", but more often considered the effects of witches' ointments to be demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in Media (communication), media such as comics, video ...

ic or satanic.

Use patterns

Decoctions ofdeliriant

Deliriants are a subclass of hallucinogen. The term was coined in the early 1980s to distinguish these drugs from psychedelics and dissociatives such as LSD and ketamine, respectively, due to their primary effect of causing delirium, as oppose ...

nightshades (such as henbane, belladonna, mandrake, or datura

''Datura'' is a genus of nine species of highly poisonous, vespertine-flowering plants belonging to the nightshade family Solanaceae. They are commonly known as thornapples or jimsonweeds, but are also known as devil's trumpets (not to be co ...

) were used in European witchcraft. All of these plants contain hallucinogenic alkaloids

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

of the tropane family, including hyoscyamine

Hyoscyamine (also known as daturine or duboisine) is a naturally occurring tropane alkaloid and plant toxin. It is a secondary metabolite found in certain plants of the family Solanaceae, including henbane, mandrake, angel's trumpets, jims ...

, atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically given ...

and scopolamine

Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine, or Devil's Breath, is a natural or synthetically produced tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic drug that is formally used as a medication for treating motion sickness and postoperative nausea and vomi ...

—the last of which is unique in that it can be absorbed through the skin. These concoctions are described in the literature variously as brews, salves

A salve is a medical ointment used to soothe the surface of the body.

Medical uses

Magnesium sulphate paste is used as a drawing salve to treat small boils and infected wounds and to remove 'draw' small splinters. Black ointment, or Ichthyol ...

, ointment

A topical medication is a medication that is applied to a particular place on or in the body. Most often topical medication means application to body surfaces such as the skin or mucous membranes to treat ailments via a large range of classes ...

s, philtres, oils

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

, and unguents. Ointments were mainly applied by rubbing on the skin, especially in sensitive areas—underarms, the pubic region, the forehead, the mucous membranes of the vagina and anus, or on areas rubbed raw ahead of time. They were often first applied to a "vehicle" to be "ridden" (an object such as a broom, pitchfork, basket, or animal skin that was rubbed against sensitive skin). All of these concoctions were made and used for the purpose of giving the witch special abilities to commune with spirits, transform into animals (lycanthropy

In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (; ; uk, Вовкулака, Vovkulaka), is an individual that can shapeshift into a wolf (or, especially in modern film, a therianthropic hybrid wolf-like creature), either purposely ...

), gain love, harm enemies, experience euphoria and sexual pleasure, and—importantly—to " fly to the witches' Sabbath".

Position of the church

Witches were not localised Christian distortions of pagans but people alleged to have both the ability and the will to employ supernatural effects for malignant ends. This belief is familiar from other cultures, and was partly inherited from paganism. The belief that witches were originally purely benign does not derive from any early textual source. However, the view of witches as malignant did stem from blatant misogyny of the time. The earliest written reference to witches as such, from Ælfric's homilies, portrays them as malign. The tendency to perceive them as healers begins only in the 19th century, withJules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and an author on other topics whose major work was a history of France and its culture. His aphoristic style emphasized his anti-clerical republicanism.

In Michelet' ...

whose novel '' La Sorcière'', published in 1862, first postulated a benign witch.

It was in the Church's interest, as it expanded, to suppress all competing Pagan methodologies of magic. This could be done only by presenting a cosmology in which Christian miracles were legitimate and credible, whereas non-Christian ones were "of the devil". Hence the following law:

While the common people were aware of the difference between witches, who they considered willing to undertake evil actions, such as cursing, and cunning folk

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services a ...

who avoided involvement in such activities, the Church attempted to blot out the distinction. In much the same way that culturally distinct non-Christian religions were all lumped together and termed merely "Pagan", so too was all magic lumped together as equally sinful and abhorrent. The ''Demonologie'' of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

explicitly condemns all magic-workers as equally guilty of the same crime against God.

"Witch" stock character

The characterization of the witch in Europe is not derived from a single source.

The familiar witch of folklore and popular superstition is a combination of numerous influences.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the recurring beliefs about witches were:

The ''

The characterization of the witch in Europe is not derived from a single source.

The familiar witch of folklore and popular superstition is a combination of numerous influences.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the recurring beliefs about witches were:

The ''Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and first ...

'' (1486) declared that the four essential points of witchcraft were renunciation of the Catholic faith, devotion of body and soul to evil, offering up unbaptized children to the Devil, and engaging in orgies that included intercourse with the Devil; in addition, witches were accused of shifting their shapes, flying through the air, abusing Christian sacraments, and confecting magical ointments.

Witches were credited with a variety of magical powers. These fall into two broad categories: those that explain the occurrence of misfortune and are thus grounded in real events, and those that are wholly fantastic.

The first category includes the powers to cause impotence, to turn milk sour, to strike people dead, to cause diseases, to raise storms, to cause infants to be stillborn, to prevent cows from giving milk, to prevent hens from laying and to blight crops. The second includes the power to fly in the air, to change form into a hare, to suckle familiar spirit

In European folklore of the medieval and early modern periods, familiars (sometimes referred to as familiar spirits) were believed to be supernatural entities that would assist witches and cunning folk in their practice of magic. According to ...

s from warts, to sail on a single plank and perhaps most absurd of all, to go to sea in an eggshell.

Witches were often believed to fly on broomsticks or distaffs

A distaff (, , also called a rock"Rock." ''The Oxford English Dictionary''. 2nd ed. 1989.), is a tool used in spinning. It is designed to hold the unspun fibers, keeping them untangled and thus easing the spinning process. It is most commonly ...

, or occasionally upon unwilling human beings, who would be called 'hag-ridden'. Horses found sweating in their stalls in the morning were also said to be hag-ridden.

The accused witch Isobel Gowdie gave the following charm as her means of transmuting herself into a hare:

Especially in media aimed at children (such as

Especially in media aimed at children (such as fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful beings. In most cult ...

s), witches are often depicted as wicked old women with wrinkled skin and pointy hats, clothed in black or purple, with wart

Warts are typically small, rough, hard growths that are similar in color to the rest of the skin. They typically do not result in other symptoms, except when on the bottom of the feet, where they may be painful. While they usually occur on the ...

s on their noses and sometimes long claw

A claw is a curved, pointed appendage found at the end of a toe or finger in most amniotes (mammals, reptiles, birds). Some invertebrates such as beetles and spiders have somewhat similar fine, hooked structures at the end of the leg or tarsus ...

-like fingernails. Like the Three Witches

The Three Witches, also known as the Weird Sisters or Wayward Sisters, are characters in William Shakespeare's play ''Macbeth'' (c. 1603–1607). The witches eventually lead Macbeth to his demise, and they hold a striking resemblance to the ...

from ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'', they are often portrayed as concocting potions in large cauldrons. Witches typically ride through the air on a broomstick as in the Harry Potter

''Harry Potter'' is a series of seven fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, all of whom are students at ...

universe or in more modern spoof versions, a vacuum cleaner

A vacuum cleaner, also known simply as a vacuum or a hoover, is a device that causes suction in order to remove dirt from floors, upholstery, draperies, and other surfaces. It is generally electrically driven.

The dirt is collected by either a ...

as in the '' Hocus Pocus'' universe. They are often accompanied by black cat

A black cat is a domestic cat with black fur that may be a mixed or specific breed, or a common domestic cat of no particular breed. The Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA) recognizes 22 cat breeds that can come with solid black coats. The Bombay b ...

s. One of the most famous modern depictions is the Wicked Witch of the West

The Wicked Witch of the West is a fictional character who appears in the classic children's novel '' The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900), created by American author L. Frank Baum. In Baum's subsequent ''Oz'' novels, it is the Nome King who is ...

, in L. Frank Baum's '' The Wonderful Wizard of Oz''.

Witches also appear as villains in many 19th- and 20th-century fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful beings. In most cult ...

s, folk tales and children's stories, such as " Snow White", "Hansel and Gretel

"Hansel and Gretel" (; german: Hänsel und Gretel ) is a German fairy tale collected by the German Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 in ''Grimm's Fairy Tales'' (KHM 15). It is also known as Little Step Brother and Little Step Sister.

Hansel ...

", "Sleeping Beauty

''Sleeping Beauty'' (french: La belle au bois dormant, or ''The Beauty in the Sleeping Forest''; german: Dornröschen, or ''Little Briar Rose''), also titled in English as ''The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods'', is a fairy tale about a princess cu ...

", and many other stories recorded by the Brothers Grimm

The Brothers Grimm ( or ), Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), were a brother duo of German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers, and authors who together collected and published folklore. They are among th ...

. Such folktales typically portray witches as either remarkably ugly hags or remarkably beautiful young women.

In the novel by Fernando de Rojas, Celestina Celestina may refer to:

In arts and entertainment:

*''La Celestina'', a 15th-century Spanish novel

*Celestina (novel), ''Celestina'' (novel), an 18th-century English work by poet Charlotte Turner Smith

*''La Celestina'', Spanish title of ''The Want ...

is an old prostitute who commits pimping and witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

in order to arrange sexual relationships.

Witches may also be depicted as essentially good, as in Archie Comics' long running ''Sabrina the Teenage Witch

''Sabrina the Teenage Witch'' is a comic book series published by Archie Comics about the adventures of a fictional American teenager named Sabrina Spellman. Sabrina was created by writer George Gladir and artist Dan DeCarlo, and first appeare ...

'' series, Terry Pratchett's '' Discworld'' novels, in Hayao Miyazaki's 1989 film '' Kiki's Delivery Service'', or the television series ''Charmed

''Charmed'' is an American fantasy drama television series created by Constance M. Burge and produced by Aaron Spelling and his production company Spelling Television, with Brad Kern serving as showrunner. The series was originally broadcas ...

'' (1998–2006). Following the film '' The Craft'', popular fictional depictions of witchcraft have increasingly drawn from Wicca

Wicca () is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religion categorise it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and w ...

n practices, portraying witchcraft as having a religious basis and witches as humans of normal appearance.

See also

References

Further reading

* Barry, Jonathan, Marianne Hester, and Gareth Roberts, eds. ''Witchcraft in early modern Europe: studies in culture and belief'' (Cambridge UP, 1998). * Brauner, Sigrid. ''Fearless wives and frightened shrews: the construction of the witch in early modern Germany'' (Univ of Massachusetts Press, 2001). * Briggs, Robin. ''Witches & neighbours: the social and cultural context of European witchcraft'' (Viking, 1996). * Clark, Stuart. ''Thinking with demons: the idea of witchcraft in early modern Europe'' (Oxford University Press, 1999). * Even-Ezra, A., “Cursus: an early thirteenth century source for nocturnal flights and ointments in the work of Roland of Cremona,” Magic, Ritual and Witchcraft 12/2 (Winter 2017), 314–330. * Kors, A.C. and E. Peters, eds. ''Witchcraft in Europe 400–1700''. (2nd ed. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001). . * Martin, Lois. ''The History Of Witchcraft: Paganism, Spells, Wicca and more.'' (Oldcastle Books, 2015), popular history. * Monter, E. William. ''Witchcraft in France and Switzerland: the Borderlands during the Reformation'' (Cornell University Press, 1976). * Monter, E. William. "The historiography of European witchcraft: progress and prospects". ''journal of interdisciplinary history'' 2#4 (1972): 435–451in JSTOR

* . * Scarre, Geoffrey, and John Callow. ''Witchcraft and magic in sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Europe'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001). * Waite, Gary K. ''Heresy, Magic and Witchcraft in early modern Europe'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003). {{Witchcraft European witchcraft