European wars of religion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in

The

The

After numerous minor incidents and provocations from both sides, a Catholic priest was executed in the Thurgau in May 1528, and the Protestant pastor J. Keyser was burned at the stake in Schwyz in 1529. The last straw was the installation of a Catholic

After numerous minor incidents and provocations from both sides, a Catholic priest was executed in the Thurgau in May 1528, and the Protestant pastor J. Keyser was burned at the stake in Schwyz in 1529. The last straw was the installation of a Catholic

Following the

Following the

By 1617, Germany was bitterly divided, and it was clear that Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, would die without an heir. His lands would therefore fall to his nearest male relative, his cousin Ferdinand of

By 1617, Germany was bitterly divided, and it was clear that Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, would die without an heir. His lands would therefore fall to his nearest male relative, his cousin Ferdinand of  The major impact of the Thirty Years' War, in which mercenary armies were extensively used, was the devastation of entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread

The major impact of the Thirty Years' War, in which mercenary armies were extensively used, was the devastation of entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread

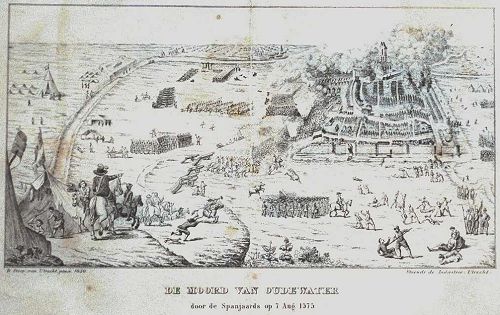

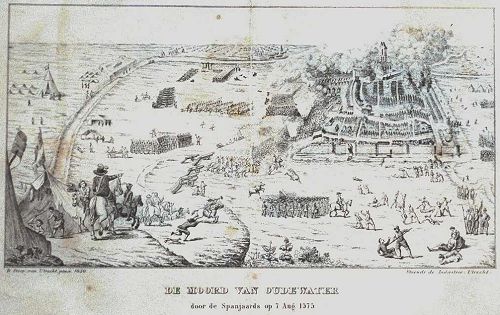

Philip gave full power to Alva in 1567. Alva's judgment was that of a soldier trained in Spanish discipline and piety. His object was to crush the rebels without mercy on the basis that every concession strengthens the opposition. Alva hand-picked an army of 10,000 men. He issued them the finest in armor while attending to their baser needs by hiring 2,000 prostitutes. Alva installed himself as Governor General and appointed a

Philip gave full power to Alva in 1567. Alva's judgment was that of a soldier trained in Spanish discipline and piety. His object was to crush the rebels without mercy on the basis that every concession strengthens the opposition. Alva hand-picked an army of 10,000 men. He issued them the finest in armor while attending to their baser needs by hiring 2,000 prostitutes. Alva installed himself as Governor General and appointed a  While Alva rested, he sent his son Don Fadrique to revenge the Beggar's atrocities. Don Fadrique's troops indiscriminately sacked homes, monasteries and churches. They stole the jewels and costly robes of the religious. They trampled consecrated hosts, butchered men and violated women. No distinction was made between Catholic or Protestant. His army crushed the weak defenses of Zutphen and put nearly every man in town to death, hanging some by the feet while drowning 500 others. Sometime later after brief resistance, little

While Alva rested, he sent his son Don Fadrique to revenge the Beggar's atrocities. Don Fadrique's troops indiscriminately sacked homes, monasteries and churches. They stole the jewels and costly robes of the religious. They trampled consecrated hosts, butchered men and violated women. No distinction was made between Catholic or Protestant. His army crushed the weak defenses of Zutphen and put nearly every man in town to death, hanging some by the feet while drowning 500 others. Sometime later after brief resistance, little

Philip's half brother, the famous Don John, was placed in charge of the Spanish troops who, feeling cheated at not being able to pillage Zeirikzee, mutinied and began a campaign of indiscriminate plunder and violence. This " Spanish Fury" was used by William to reinforce his arguments to ally all the Netherlands' Provinces with him. The Union of Brussels was formed only to be dissolved later out of intolerance towards the religious diversity of its members. Calvinists began their wave of uncontrolled atrocities aimed at the Catholics. This divisiveness gave Spain the opportunity to send

Philip's half brother, the famous Don John, was placed in charge of the Spanish troops who, feeling cheated at not being able to pillage Zeirikzee, mutinied and began a campaign of indiscriminate plunder and violence. This " Spanish Fury" was used by William to reinforce his arguments to ally all the Netherlands' Provinces with him. The Union of Brussels was formed only to be dissolved later out of intolerance towards the religious diversity of its members. Calvinists began their wave of uncontrolled atrocities aimed at the Catholics. This divisiveness gave Spain the opportunity to send

In a pattern soon to become familiar in the Netherlands and Scotland, underground

In a pattern soon to become familiar in the Netherlands and Scotland, underground  The Protestant army laid siege to several cities in the Poitou and

The Protestant army laid siege to several cities in the Poitou and

The King knew that he had to take Paris if he stood any chance of ruling all of France, and this was no easy task. The Catholic League's presses and supporters continued to spread stories about atrocities committed against Catholic priests and the laity in Protestant England, such as the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. The city prepared to fight to the death rather than accept a Calvinist king. The

The King knew that he had to take Paris if he stood any chance of ruling all of France, and this was no easy task. The Catholic League's presses and supporters continued to spread stories about atrocities committed against Catholic priests and the laity in Protestant England, such as the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. The city prepared to fight to the death rather than accept a Calvinist king. The

Charles II landed in Scotland at Garmouth in Moray on 23 June 1650 and signed the 1638 National Covenant and the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant immediately after coming ashore. With his original Scottish Royalist followers and his new Covenanter allies, King Charles II became the greatest threat facing the new English republic. In response to the threat, Cromwell left some of his lieutenants in Ireland to continue the suppression of the Irish Royalists and returned to England.

Cromwell arrived in Scotland on 22 July 1650 and proceeded to lay siege to Edinburgh. By the end of August disease and a shortage of supplies had reduced his army, and he had to order a retreat towards his base at Dunbar. A Scottish army, assembled under the command of David Leslie, tried to block the retreat, but Cromwell defeated them at the Battle of Dunbar on 3 September. Cromwell's army then took Edinburgh, and by the end of the year his army had occupied much of southern Scotland.

In July 1651, Cromwell's forces crossed the Firth of Forth into Fife and defeated the Scots at the Battle of Inverkeithing (20 July 1651). The New Model Army advanced towards

Charles II landed in Scotland at Garmouth in Moray on 23 June 1650 and signed the 1638 National Covenant and the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant immediately after coming ashore. With his original Scottish Royalist followers and his new Covenanter allies, King Charles II became the greatest threat facing the new English republic. In response to the threat, Cromwell left some of his lieutenants in Ireland to continue the suppression of the Irish Royalists and returned to England.

Cromwell arrived in Scotland on 22 July 1650 and proceeded to lay siege to Edinburgh. By the end of August disease and a shortage of supplies had reduced his army, and he had to order a retreat towards his base at Dunbar. A Scottish army, assembled under the command of David Leslie, tried to block the retreat, but Cromwell defeated them at the Battle of Dunbar on 3 September. Cromwell's army then took Edinburgh, and by the end of the year his army had occupied much of southern Scotland.

In July 1651, Cromwell's forces crossed the Firth of Forth into Fife and defeated the Scots at the Battle of Inverkeithing (20 July 1651). The New Model Army advanced towards

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

during the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries. Fought after the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

began in 1517, the wars disrupted the religious and political order in the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

countries of Europe, or Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

. Other motives during the wars involved revolt, territorial ambitions and great power conflicts. By the end of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

(1618–1648), Catholic France had allied with the Protestant forces against the Catholic Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

. The wars were largely ended by the Peace of Westphalia (1648), which established a new political order that is now known as Westphalian sovereignty.

The conflicts began with the minor Knights' Revolt (1522), followed by the larger German Peasants' War (1524–1525) in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

. Warfare intensified after the Catholic Church began the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

in 1545 against the growth of Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. The conflicts culminated in the Thirty Years' War, which devastated Germany and killed one third of its population, a mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

twice that of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The Peace of Westphalia broadly resolved the conflicts by recognising three separate Christian traditions in the Holy Roman Empire: Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, and Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

.Treaty of Münster 1648 Although many European leaders were sickened by the bloodshed by 1648, smaller religious wars continued to be waged until the 1710s, including the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bi ...

(1639–1651) in the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

, the Savoyard–Waldensian wars (1655–1690), and the Toggenburg War (1712) in the Western Alps.

Definitions and discussions

The European wars of religion are also known as the Wars of the Reformation. In 1517,Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

's '' Ninety-five Theses'' took only two months to spread throughout Europe with the help of the printing press, overwhelming the abilities of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and the papacy to contain it. In 1521, Luther was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

, sealing the schism within Western Christendom between the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

s and opening the door for other Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s to resist the power of the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

.

Although most of the wars ended with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, religious conflicts continued to be fought in Europe until at least the 1710s. These included the Savoyard–Waldensian wars (1655–1690), the Nine Years' War (1688–1697, including the Glorious Revolution and the Williamite War in Ireland), and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714). Whether these should be included in the European wars of religion depends on how one defines a "war of religion

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to ...

", and whether these wars can be considered "European" (i.e. international rather than domestic).Onnekink, pp. 9–10.

The religious nature of the wars has also been debated, and contrasted with other factors at play, such as national, dynastic (e.g. they could often simultaneously be characterised as wars of succession

A war of succession is a war prompted by a succession crisis in which two or more individuals claim the right of successor to a deceased or deposed monarch. The rivals are typically supported by factions within the royal court. Foreign pow ...

), and financial interests. Scholars have pointed out that some European wars of this period were not caused by disputes occasioned by the Reformation, such as the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

(1494–1559, only involving Catholics), as well as the Northern Seven Years' War (1563–1570, only involving Lutherans). Others emphasise the fact that cross-religious alliances existed, such as the Lutheran duke Maurice of Saxony

Maurice (21 March 1521 – 9 July 1553) was Duke (1541–47) and later Elector (1547–53) of Saxony. His clever manipulation of alliances and disputes gained the Albertine branch of the Wettin dynasty extensive lands and the electoral dignity.

...

assisting the Catholic emperor Charles V in the first Schmalkaldic War in 1547 in order to become the Saxon elector instead of John Frederick, his Lutheran cousin, while the Catholic king Henry II of France

Henry II (french: Henri II; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I and Duchess Claude of Brittany, he became Dauphin of France upon the death of his elder bro ...

supported the Lutheran cause in the Second Schmalkaldic War

The Second Schmalkaldic War, also known as the Princes' Revolt (German: ''Fürstenaufstand'', ''Fürstenkrieg'' or ''Fürstenverschwörung''), was an uprising of German Protestant princes led by elector Maurice of Saxony against the Catholic emp ...

in 1552 to secure French bases in modern-day Lorraine. The ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' maintains that " hewars of religion of this period erefought mainly for confessional security and political gain."

In the late 20th century, a number of revisionist historians such as William M. Lamont regarded the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

(1642–1651) as a religious war, with John Morrill (1993) stating: "The English Civil War was not the first European revolution: it was the last of the Wars of Religion." This view has been criticised by various pre-, post- and anti-revisionist historians. Glen Burgess (1998) examined political propaganda written by the Parliamentarian politicians and clerics at the time, noting that many were or may have been motivated by their Puritan religious beliefs to support the war against the perceived Catholic king Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. He was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of Scotland, but after ...

, but tried to express and legitimise their opposition and rebellion in terms of a legal revolt against a monarch who had violated crucial constitutional principles and thus had to be overthrown. They even warned their Parliamentarian allies to not make overt use of religious arguments in making their case for war against the king. In some cases, it may be argued that they hid their pro-Anglican and anti-Catholic motives behind legal parliance, for example by emphasising that the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

was the legally established religion: "Seen in this light, the defenses of Parliament's war, with their apparent legal-constitutional thrust, are not at all ways of saying that the struggle was not religious. On the contrary, they are ways of saying that it was." Burgess concluded: " e Civil War left behind it just the sort of evidence that we could reasonably expect a war of religion to leave."

Overview of the wars

Individual conflicts that may be distinguished within this topic include: * Pre-Reformation wars: ** TheOldcastle Revolt

The Oldcastle Revolt was a Lollard uprising directed against the Catholic Church and the English king, Henry V. The revolt was led by John Oldcastle, taking place on the night of 9/10 January 1414. The rebellion was crushed following a decisive ...

(1414) in England (sometimes considered to have "foreshadowed the wars of religion")

** The Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, Eur ...

(1419–1434) in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown were a number of incorporated states in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods connected by feudal relations under the Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted of the Kingdom o ...

* Conflicts immediately connected with the Reformation:

** The Knights' Revolt (1522–1523) in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

Onnekink, p. 2.

** The First Dalecarlian Rebellion

The Dalecarlian rebellions ( sv, Dalupproren) were a series of Swedish rebellions which took place in Dalarna in Sweden: the First Dalecarlian Rebellion in 1524-1525, the Second Dalecarlian Rebellion in 1527–1528, and the Third Dalecarlian Reb ...

(1524–1525) in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

.

** The German Peasants' War (1524–1526) in the Holy Roman Empire

** The Second Dalecarlian Rebellion

The Dalecarlian rebellions ( sv, Dalupproren) were a series of Swedish rebellions which took place in Dalarna in Sweden: the First Dalecarlian Rebellion in 1524-1525, the Second Dalecarlian Rebellion in 1527–1528, and the Third Dalecarlian Reb ...

(1527–1528) in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

.

** The Wars of Kappel

The wars of Kappel (''Kappelerkriege'') is a collective term for two armed conflicts fought near Kappel am Albis between the Catholic and the Protestant cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy during the Reformation in Switzerland.

First War

The ...

(1529–1531) in the Old Swiss Confederacy

** The Tudor conquest of Ireland (1529–1603) on the Catholic population of Ireland by the Tudor kings of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and their Protestant allies

*** The Kildare Rebellion (1534–1535)

*** The First Desmond Rebellion

The Desmond Rebellions occurred in 1569–1573 and 1579–1583 in the Irish province of Munster.

They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond, the head of the Fitzmaurice/FitzGerald Dynasty in Munster, and his followers, the Geraldines an ...

(1569–1573)

*** The Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–1583)

*** The Nine Years' War (1593–1603)

** The Third Dalecarlian Rebellion

The Dalecarlian rebellions ( sv, Dalupproren) were a series of Swedish rebellions which took place in Dalarna in Sweden: the First Dalecarlian Rebellion in 1524-1525, the Second Dalecarlian Rebellion in 1527–1528, and the Third Dalecarlian Reb ...

(1531–1533) in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

.

** The War of Two Kings (1531–1532) in the Kalmar Union (Denmark and Norway)

** The Count's Feud (1534–1536) in the Kalmar Union (Denmark and Norway)

** The Münster rebellion (1534–1535) in the Prince-Bishopric of Münster

The Prince-Bishopric of Münster (german: Fürstbistum Münster; Bistum Münster, Hochstift Münster) was a large ecclesiastical principality in the Holy Roman Empire, located in the northern part of today's North Rhine-Westphalia and western L ...

** The Anabaptist riot

The Anabaptist riot of Amsterdam or ''Wederdopersoproer'' generally refers to an event on 10 May 1535 in which 40 Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the mi ...

(1535) in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

** Olav Engelbrektsson's rebellion

Olav Engelbrektsson (, Trondenes, Norway – 7 February 1538, Lier, Duchy of Brabant, Habsburg Netherlands) was the 28th Archbishop of Norway from 1523 to 1537, the Regent of Norway from 1533 to 1537, a member and later president of the ''Ri ...

(1536–1537) in Norway

** Bigod's rebellion (1537) in England

** The Dacke War (1542–1543) in Sweden

* Conflicts after the death of Martin Luther:

** The Schmalkaldic War (1546–1547) in the Holy Roman Empire

** The Prayer Book Rebellion (1549) in England

** The Battle of Sauðafell

The Battle of Sauðafell (''Orrustan á Sauðafelli'') occurred in 1550, when the forces of Catholic Bishop Jón Arason clashed with the forces of Daði Guðmundsson of Snóksdalur.

Location

Sauðafell was an important part of Daði's fief in ...

(1550) on Iceland

** The Second Schmalkaldic War

The Second Schmalkaldic War, also known as the Princes' Revolt (German: ''Fürstenaufstand'', ''Fürstenkrieg'' or ''Fürstenverschwörung''), was an uprising of German Protestant princes led by elector Maurice of Saxony against the Catholic emp ...

or Princes' Revolt

The Second Schmalkaldic War, also known as the Princes' Revolt (German: ''Fürstenaufstand'', ''Fürstenkrieg'' or ''Fürstenverschwörung''), was an uprising of German Protestant princes led by elector Maurice of Saxony against the Catholic emp ...

(1552–1555)Onnekink, p. 3.

** Wyatt's rebellion (1554) in England over Mary I of England's decision to marry the Catholic non-English prince Philip II of Spain. Mary's repression of the rebellion earned her the nickname "Bloody Mary" amongst Protestants.

** The French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mil ...

(1562–1598) in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

** The Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Ref ...

(1566/68–1648) in the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

** The Cologne War (1583–1588) in the Electorate of Cologne

** The Strasbourg Bishops' War (1592–1604) in the Prince-Bishopric of Strasbourg

** The War against Sigismund (1598–1599) in the Polish–Swedish union

The Polish–Swedish union was a short-lived personal union between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Kingdom of Sweden between 1592 and 1599. It began when Sigismund III Vasa, elected King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, was ...

** The Bocskai uprising (1604–1606) in Hungary and Transylvania

** The War of the Jülich Succession (1609–10, 1614) in the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

The so-called United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg was a territory in the Holy Roman Empire between 1521 and 1666, formed from the personal union of the duchies of Jülich, Cleves and Berg.

The name was resurrected after the Congress of Vie ...

* The Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

(1618–1648), affecting the Holy Roman Empire including the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

and Bohemia and Moravia, France, Denmark-Norway and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

** Bohemian Revolt (1618–1620) between the Protestant nobility of the Bohemian Crown

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown were a number of incorporated states in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods connected by feudal relations under the Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted of the Kingdom of B ...

and their Catholic Habsburg king. This revolt started the Thirty Years' War, causing additional conflicts elsewhere in Europe, and subsuming other already ongoing conflicts.

** Hessian War

The Hessian War (german: Hessenkrieg), in its wider sense sometimes also called the Hessian Wars (''Hessenkriege''), was a drawn out conflict that took place between 1567 and 1648, sometimes pursued through diplomatic means, sometimes by military ...

(1567–1648) between the Lutheran Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Darmstadt) was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hesse. It was formed in 1567 following the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse bet ...

(member of the Catholic League) and the Calvinist Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (member of the Protestant Union)

* The Huguenot rebellions (1621–1629) in France

* The Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bi ...

(1639–1651), affecting England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

** Bishops' Wars (1639–1640)

** English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

(1642–1651)

** Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1644–1651)

** Irish Confederate Wars (1641–1653) and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–1653)Onnekink, p. 7.

* The post-Westphalian wars:

** The Düsseldorf Cow War (1651)

** The Savoyard–Waldensian wars (1655–1690) beginning with the Piedmontese Easter

The Piedmontese Easter (Italian: ''Pasque piemontesi'', French: ''Pâques piémontaises'' or ''Pâques vaudoises'') was a series of massacres on Waldensians (also known as Waldenses or Vaudois) by Savoyard troops in the Duchy of Savoy in 1655.

...

(''Pasque piemontesi'') of April 1655, in the Duchy of Savoy

** The First War of Villmergen (1656) in the Old Swiss Confederacy

** The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667) between England and the Dutch Republic

** The Nine Years' War (1688–1697)

*** The Glorious Revolution (1688–1689)

*** The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691)

*** The Jacobite rising of 1689 in Scotland saw Roman Catholics and Anglican Tories supporting the deposed Catholic king James Stuart take up arms against the newly enthroned Calvinist William of Orange and his Presbyterian Covenanter allies; the religious component may be regarded as secondary to the dynastic factor, however.

** The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) across Europe had a strong religious component

** The War in the Cevennes (1702–1710) in France

** The Toggenburg War (Second War of Villmergen) (1712) in the Old Swiss Confederacy

Holy Roman Empire

The

The Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, encompassing present-day Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and surrounding territory, was the area most devastated by the wars of religion. The Empire was a fragmented collection of practically independent states with an elected Holy Roman Emperor as their titular ruler; after the 14th century, this position was usually held by a Habsburg. The Austrian House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

, who remained Catholic, was a major European power in its own right, ruling over some eight million subjects in present-day Germany, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Bohemia and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

. The Empire also contained regional powers, such as Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

, the Electorate of Saxony, the Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg (german: link=no, Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Brandenburg developed out ...

, the Electorate of the Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate (german: Kurpfalz) or the Palatinate (), officially the Electorate of the Palatinate (), was a state that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The electorate had its origins under the rulership of the Counts Palatine o ...

, the Landgraviate of Hesse, the Archbishopric of Trier

The Diocese of Trier, in English historically also known as ''Treves'' ( IPA "tɾivz") from French ''Trèves'', is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic church in Germany.Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Württ ...

. A vast number of minor independent duchies, free imperial cities, abbeys, bishoprics, and small lordships of sovereign families rounded out the Empire.

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, from its inception at Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the River Elbe, north of ...

in 1517, found a ready reception in Germany, as well as German-speaking parts of Hussite Bohemia (where the Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, Eur ...

took place from 1419 to 1434, and Hussites remained a majority of the population until the 1620 Battle of White Mountain). The preaching of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

and his many followers raised tensions across Europe. In Northern Germany, Luther adopted the tactic of gaining the support of the local princes and city elites in his struggle to take over and re-establish the church along Lutheran lines. The Elector of Saxony, the Landgrave of Hesse, and other North German princes not only protected Luther from retaliation from the edict of outlawry issued by the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fro ...

, but also used state power to enforce the establishment of Lutheran worship in their lands, in what is called the Magisterial Reformation. Church property was seized, and Catholic worship was forbidden in most territories that adopted the Lutheran Reformation. The political conflicts thus engendered within the Empire led almost inevitably to war.

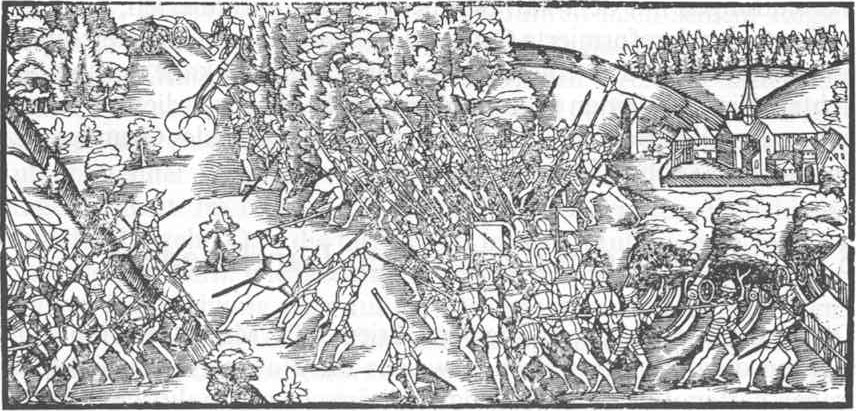

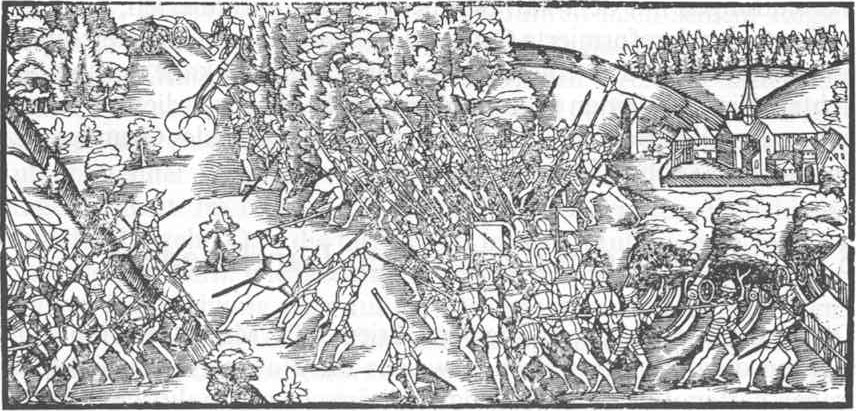

The Knights' Revolt of 1522 was a revolt by a number of Protestant and religious humanist German knights led by Franz von Sickingen, against the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Emperor. It has also been called the "Poor Barons' Rebellion". The revolt was short-lived but would inspire the bloody German Peasants' War of 1524–1526.

Rebellions of Anabaptists and other radicals

The first large-scale wave of violence was engendered by the more radical wing of the Reformation movement, whose adherents wished to extend the wholesale reform of the Church into a similarly wholesale reform of society in general. This was a step that the princes supporting Luther were not willing to countenance. The German Peasants' War of 1524/1525 was apopular revolt

This is a chronological list of conflicts in which peasants played a significant role.

Background

The history of peasant wars spans over two thousand years. A variety of factors fueled the emergence of the peasant revolt phenomenon, including:

...

inspired by the teachings of the radical reformers. It consisted of a series of economic as well as religious revolts by Anabaptist peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

s, townsfolk and nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

. The conflict took place mostly in southern, western and central areas of modern Germany but also affected areas in neighboring modern Switzerland, Austria and the Netherlands (for example, the 1535 Anabaptist riot

The Anabaptist riot of Amsterdam or ''Wederdopersoproer'' generally refers to an event on 10 May 1535 in which 40 Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the mi ...

in Amsterdam). At its height, in the spring and summer of 1525, it involved an estimated 300,000 peasant insurgents. Contemporary estimates put the dead at 100,000. It was Europe's largest and most widespread popular uprising before the 1789 French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

.

Because of their revolutionary political ideas, radical reformers like Thomas Müntzer were compelled to leave the Lutheran cities of North Germany in the early 1520s. They spread their revolutionary religious and political doctrines into the countryside of Bohemia, Southern Germany, and Switzerland. Starting as a revolt against feudal oppression, the peasants' uprising became a war against all constituted authorities, and an attempt to establish by force an ideal Christian commonwealth. The total defeat of the insurgents at Frankenhausen on 15 May 1525, was followed by the execution of Müntzer and thousands of his peasant followers. Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

rejected the demands of the insurgents and upheld the right of Germany's rulers to suppress the uprisings, setting out his views in his polemic ''Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants

''Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants'' (german: link=no, Wider die Mordischen und Reubischen Rotten der Bawren) is a piece written by Martin Luther in response to the German Peasants' War. Beginning in 1524 and ending in 1525, th ...

''. This played a major part in the rejection of his teachings by many German peasants, particularly in the south.

After the Peasants' War, a second and more determined attempt to establish a theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fr ...

was made at Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

, in Westphalia (1532–1535). Here a group of prominent citizens, including the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

pastor turned Anabaptist Bernhard Rothmann

Bernhard (or Bernard) Rothmann (c. 1495 – c. 1535) was a 16th-century radical and Anabaptist leader in the city of Münster. He was born in Stadtlohn, Westphalia, around 1495.

Overview

In the late 1520s Bernard Rothmann became the leader for ...

, Jan Matthys, and Jan Bockelson ("John of Leiden") had little difficulty in obtaining possession of the town on 5 January 1534. Matthys identified Münster as the " New Jerusalem", and preparations were made to not only hold what had been gained, but to proceed from Münster toward the conquest of the world.

Claiming to be the successor of David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, John of Leiden was installed as king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

. He legalized polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marr ...

and took sixteen wives, one of whom he personally beheaded in the marketplace. Community of goods was also established. After obstinate resistance, the town was taken by the besiegers on 24 June 1535, and then Leiden and some of his more prominent followers were executed in the marketplace.

Swiss Confederacy

In 1529 under the lead of Huldrych Zwingli, the Protestant canton and city ofZürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Z ...

had concluded with other Protestant cantons a defence alliance, the ''Christliches Burgrecht'', which also included the cities of Konstanz

Konstanz (, , locally: ; also written as Constance in English) is a university city with approximately 83,000 inhabitants located at the western end of Lake Constance in the south of Germany. The city houses the University of Konstanz and was t ...

and Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label= Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label= Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the ...

. The Catholic cantons in response had formed an alliance with Ferdinand of Austria.

After numerous minor incidents and provocations from both sides, a Catholic priest was executed in the Thurgau in May 1528, and the Protestant pastor J. Keyser was burned at the stake in Schwyz in 1529. The last straw was the installation of a Catholic

After numerous minor incidents and provocations from both sides, a Catholic priest was executed in the Thurgau in May 1528, and the Protestant pastor J. Keyser was burned at the stake in Schwyz in 1529. The last straw was the installation of a Catholic vogt

During the Middle Ages, an (sometimes given as modern English: advocate; German: ; French: ) was an office-holder who was legally delegated to perform some of the secular responsibilities of a major feudal lord, or for an institution such as ...

at Baden, and Zürich declared war on 8 June (First War of Kappel

The First War of Kappel (''Erster Kappelerkrieg'') was an armed conflict in 1529 between the Protestant and the Catholic cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy during the Reformation in Switzerland. It ended, without any single battle having been ...

), occupied the Thurgau and the territories of the Abbey of St. Gall, and marched to Kappel at the border to Zug. Open war was avoided by means of a peace agreement (''Erster Landfriede

Under the law of the Holy Roman Empire, a ''Landfrieden'' or ''Landfriede'' (Latin: ''constitutio pacis'', ''pax instituta'' or ''pax jurata'', variously translated as "land peace", or "public peace") was a contractual waiver of the use of legiti ...

'') that was not exactly favourable to the Catholic side, which had to dissolve its alliance with the Austrian Habsburgs. Tensions remained essentially unresolved.

On 11 October 1531, the Catholic cantons decisively defeated the forces of Zürich in the Second War of Kappel. The Zürich troops had little support from allied Protestant cantons, and Huldrych Zwingli was killed on the battlefield, along with twenty-four other pastors. After the defeat, the forces of Zürich regrouped and attempted to occupy the Zugerberg

The Zugerberg is a mountain overlooking Zug and Lake Zug in the Zug

Zug ( Standard German: , Alemannic German: ; french: Zoug it, Zugo rm, Zug New Latin: ''Tugium'')named in the 16th century is the largest town and capital of the Swiss canto ...

, and some of them camped on the ''Gubel'' hill near Menzingen

Menzingen is a municipality in the canton of Zug in Switzerland.

History

Menzingen is first mentioned around 1217-22 as ''Meincingin''.

The traditionalist Society of Saint Pius X, which is said to have broken with the Vatican over "doctrinal ...

. A small force of Aegeri succeeded in routing the camp, and the demoralized Zürich force had to retreat, forcing the Protestants to agree to a peace treaty to their disadvantage. Switzerland was to be divided into a patchwork of Protestant and Catholic cantons, with the Protestants tending to dominate the larger cities, and the Catholics the more rural areas.

In 1656, tensions between Protestants and Catholics re-emerged and led to the outbreak of the First War of Villmergen. The Catholics were victorious and able to maintain their political dominance. The Toggenburg War in 1712 was a conflict between Catholic and Protestant cantons. According to the Peace of Aarau of 11 August 1712 and the Peace of Baden of 16 June 1718, the war ended with the end of Catholic hegemony. The Sonderbund War of 1847 was also based on religion.

Schmalkaldic Wars and other early conflicts

Following the

Following the Diet of Augsburg

The Diet of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sessi ...

in 1530, the Emperor demanded that all religious innovations not authorized by the Diet be abandoned by 15 April 1531. Failure to comply would result in prosecution by the Imperial Court. In response, the Lutheran princes who had set up Protestant churches in their own realms met in the town of Schmalkalden

Schmalkalden () is a town in the Schmalkalden-Meiningen district, in the southwest of the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is on the southern slope of the Thuringian Forest at the Schmalkalde river, a tributary to the Werra. , the town had a p ...

in December 1530. Here they banded together to form the Schmalkaldic League (german: Schmalkaldischer Bund), an alliance designed to protect themselves from the Imperial action. Its members eventually intended the League to replace the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

itself, and each state was to provide 10,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry for mutual defense. In 1532 the Emperor, pressed by external troubles, stepped back from confrontation, offering the "Peace of Nuremberg

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

", which suspended all action against the Protestant states pending a General Council of the Church. The moratorium kept peace in the German lands for over a decade, yet Protestantism became further entrenched, and spread, during its term.

The peace finally ended in the Schmalkaldic War (german: Schmalkaldischer Krieg), a brief conflict between 1546 and 1547 between the forces of Charles V and the princes of the Schmalkaldic League. The conflict ended with the advantage of the Catholics, and the Emperor was able to impose the Augsburg Interim, a compromise allowing slightly modified worship, and supposed to remain in force until the conclusion of a General Council of the Church. However various Protestant elements rejected the Interim, and the Second Schmalkaldic War

The Second Schmalkaldic War, also known as the Princes' Revolt (German: ''Fürstenaufstand'', ''Fürstenkrieg'' or ''Fürstenverschwörung''), was an uprising of German Protestant princes led by elector Maurice of Saxony against the Catholic emp ...

broke out in 1552, which would last until 1555.

The Peace of Augsburg (1555), signed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, confirmed the result of the 1526 Diet of Speyer and ended the violence between the Lutherans and the Catholics in Germany. It stated that:

* German princes could choose the religion (Lutheranism or Catholicism) of their realms according to their conscience. The citizens of each state were forced to adopt the religion of their rulers (the principle of ''cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individual ...

'').

* Lutherans living in an ''ecclesiastical state'' (under the control of a bishop) could continue to practice their faith.

* Lutherans could keep the territory that they had captured from the Catholic Church since the Peace of Passau in 1552.

* The ecclesiastical leaders of the Catholic Church (bishops) that had converted to Lutheranism were required to give up their territories.

Religious tensions remained strong throughout the second half of the 16th century. The Peace of Augsburg began to unravel as some bishops converting to Protestantism refused to give up their bishoprics. This was evident from the Cologne War (1582–83), a conflict initiated when the prince-archbishop of the city converted to Calvinism. Religious tensions also broke into violence in the German free city Free city may refer to: Historical places

* Free city (antiquity) a self-governed city during the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial eras

* Free imperial city, self-governed city in the Holy Roman Empire subordinate only to the emperor

** Free City of ...

of Donauwörth in 1606, when the Lutheran majority barred the Catholic residents from holding a procession, provoking a riot. This prompted intervention by Duke Maximilian of Bavaria on behalf of the Catholics.

By the end of the 16th century the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

lands and those of southern Germany remained largely Catholic, while Lutherans predominated in the north, and Calvinists dominated in west-central Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. The latter formed the League of Evangelical Union

The Protestant Union (german: Protestantische Union), also known as the Evangelical Union, Union of Auhausen, German Union or the Protestant Action Party, was a coalition of Protestant German states. It was formed on 14 May 1608 by Frederick IV ...

in 1608.

Thirty Years' War

Styria

Styria (german: Steiermark ; Serbo-Croatian and sl, ; hu, Stájerország) is a state (''Bundesland'') in the southeast of Austria. With an area of , Styria is the second largest state of Austria, after Lower Austria. Styria is bordered ...

. Ferdinand, having been educated by the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

, was a staunch Catholic. The rejection of Ferdinand as Crown Prince by the mostly Hussite Bohemia triggered the Thirty Years' War in 1618, when his representatives were defenestrated in Prague.

The Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

was fought between 1618 and 1648, principally on the territory of today's Germany, and involved most of the major European powers. Beginning as a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, it gradually developed into a general war involving much of Europe, for reasons not necessarily related to religion. The war marked a continuation of the France-Habsburg rivalry for pre-eminence in Europe, which led later to direct war between France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

. Military intervention by external powers such as Denmark and Sweden on the Protestant side increased the duration of the war and the extent of its devastation. In the latter stages of the war, Catholic France, fearful of an increase in Habsburg power, also intervened on the Protestant side.

The major impact of the Thirty Years' War, in which mercenary armies were extensively used, was the devastation of entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread

The major impact of the Thirty Years' War, in which mercenary armies were extensively used, was the devastation of entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompan ...

and disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

devastated the population of the German states and, to a lesser extent, the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

and Italy, while bankrupting many of the powers involved. The war ended with the Treaty of Münster, a part of the wider Peace of Westphalia.

During the war, Germany's population was reduced by 30% on average. In the territory of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

, the losses had amounted to half, while in some areas an estimated two thirds of the population died. The population of the Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic sin ...

declined by a third. The Swedish army alone, which was no greater a ravager than the other armies of the Thirty Years' War, destroyed 2,000 castles, 18,000 villages and 1,500 towns during its tenure of 17 years in Germany. For decades armies and armed bands had roamed Germany like packs of wolves, slaughtering the populace like sheep. One band of marauders even styled themselves as "Werewolves". Huge damage was done to monasteries, churches and other religious institutions. The war had proved disastrous for the German-speaking parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Germany lost population and territory, and was henceforth further divided into hundreds of largely impotent semi-independent states. The Imperial power retreated to Austria and the Habsburg lands. The Netherlands and Switzerland were confirmed independent. The peace institutionalised the Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist religious divide in Germany, with populations either converting, or moving to areas controlled by rulers of their own faith.

One authority puts France's losses against Austria at 80,000 killed or wounded and against Spain (including the years 1648–1659, after Westphalia) at 300,000 dead or disabled. Sweden and Finland lost, by one calculation, 110,000 dead from all causes. Another 400,000 Germans, British, and other nationalities died in Swedish service.

Low Countries

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Netherlands, orLow Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, were engaged in a seemingly futile struggle for independence against the most dominant power of the times, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

. The most politically significant turn of events came when Charles V of Spain Charles V of Spain may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of ...

transferred sovereignty of the Low Countries to his son Philip II. At this point in history the Low Countries were a loosely associated cluster of provinces. Philip II mishandled his responsibility through a series of bungled diplomatic maneuvers. Unlike his father, he had no basic understanding of the people placed under his direction. Charles V spoke the language; Philip II did not. Charles V was raised in Brussels; Philip II was considered a foreigner.

The religious element was a decisive factor in the development of hostilities despite the fact that the Dutch people at the time were overwhelmingly Roman Catholic. Their theological basis was in the liberal tradition of Erasmus versus the conservative line of the Spanish Church. Nevertheless, Protestant religions, especially Calvinism, seeped into the Low Countries during the early part of the 16th century due to the fact that it was a major center for trade. This period was also known for the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

. Under Charles’ reign, the Low Countries were subjected to the papal form of the Inquisition where laws were rarely enforced. An incident at Rotterdam involving the rescue of several heretics from burning at the stake made Philip introduce the Spanish form of the Inquisition. This did little to promote allegiance to Spain.

Calvinism thrived in the mercantile atmosphere of the Low Countries. Businessmen liked the role of the laity in Calvinist congregations. The Roman Catholic church was viewed as an unyielding patriarch, and the pompous hierarchy of the Roman Catholic church was resented even though Catholicism had respect as an important social, moral, and political force. Merchants welcomed the "new" religion. Not to be taken lightly was the imposition of taxes on the businesses and people of the Low Countries. The taxation was unilateral in nature: it was levied by a foreign political entity and the benefit derived from the taxes went to Spain. Spain was building an empire, and the low Countries paid dearly.

In 1559, Philip appointed Margaret of Parma as governess. She held little power since her authority had been carefully limited by advisors designated by Philip. This was a means of preserving absolute control over the Low Countries and it was an excellent vehicle to promote the spread of the Inquisition. Hardly a day passed without an execution. Protestant authorities substantiate a number of accounts associated with the "justice" of Philip. One account reveals an incident where an Anabaptist was hacked to death with seven blows of a rusty sword in the presence of his wife, who died at the horror of the sight. Another tells of an enraged man who interrupted Christmas Mass, took the host, and trampled it. He was put to torture by having his right hand and foot burned away to the bane. His tongue was torn out, he was suspended over a fire and was slowly roasted to death. Margaret interceded but the atrocities continued. Even the Catholics now joined with Protestants as Philip stated that he would rather sacrifice a hundred thousand lives than change his policy. Some diplomacy was used and when a compromise was reached on 6 May 1566, Philip eased off. During the ensuing lull, Protestants brought their worship into the open. A group called the "Beggars" grew in strength and proceeded to raise a sizable army.

On 6 August 1566, Philip signed a formal instrument declaring that his offer of pardon had been gotten from him against his will. He claimed that he was not bound by the compromise of 6 May and a few days later, Philip assured the Pope that any suspension of the Inquisition was subject to papal approval. The destruction of thirty churches and monasteries followed. Protestants entered cathedrals smashing holy objects, breaking up altars and statues and smashing stained glass windows. Bodies were exhumed and corpses were stripped. Numbers of malcontents drank sacramental wine and burned missals. One Count fed the Eucharistic wafers to his parrot in defiance. It was well known that most Protestant leaders condemned the violence perpetrated by the angry mobs, but the pillage and destruction of property was considered far less criminal than burning heretics at the stake. On the political front, William of Orange saw the opportunity to amass support for a large scale insurrection aimed at procuring independence from Spain. Philip became dissatisfied with Margaret, and seized the opportunity to relieve her. The choice was crucial. Instead of selecting a successor trained in handling diplomacy, Philip sent the Duke of Alva to crush the malcontents.

Duke of Alba (Alva)

Philip gave full power to Alva in 1567. Alva's judgment was that of a soldier trained in Spanish discipline and piety. His object was to crush the rebels without mercy on the basis that every concession strengthens the opposition. Alva hand-picked an army of 10,000 men. He issued them the finest in armor while attending to their baser needs by hiring 2,000 prostitutes. Alva installed himself as Governor General and appointed a

Philip gave full power to Alva in 1567. Alva's judgment was that of a soldier trained in Spanish discipline and piety. His object was to crush the rebels without mercy on the basis that every concession strengthens the opposition. Alva hand-picked an army of 10,000 men. He issued them the finest in armor while attending to their baser needs by hiring 2,000 prostitutes. Alva installed himself as Governor General and appointed a Council of Troubles

The Council of Troubles (usual English translation of nl, Raad van Beroerten, or es, Tribunal de los Tumultos, or french: Conseil des Troubles) was the special tribunal instituted on 9 September 1567 by Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of ...

which the terrified Protestants renamed "The Council of Blood". There were nine members: seven Dutch and two Spanish. Only the two Spanish members had the power to vote, with Alva personally retaining the right of final decision on any case that interested him. Through a network of spies and informers, hardly a family in Flanders did not mourn some member arrested or killed. One morning, 1,500 were seized in their sleep and sent to jail. There were short trials held, often on the spot, for 40 or 50 at a time. In January 1568, 84 people were executed from Valenciennes alone. William of Orange decided to strike back at Spain, having organized three armies. He lost every battle and the Eighty Years' War was underway (1568–1648).

The Duke of Alva had money sent from Spain but it was intercepted by English privateers who were beginning to establish England as a viable world power. The Queen of England sent her apologies as a matter of diplomatic courtesy while unofficially enjoying Spain's troubles. Alva responded to his financial bind by imposing a new series of taxes. There was a 1% levy on all property, due immediately. He enforced a 5% perpetual tax on every transfer of realty and a 10% perpetual tax on every sale. This was Alva's downfall. Catholics, as well as Protestants, opposed him for eroding the foundations of business upon which the Dutch economy was built. What followed was a series of mutual confiscation of property as England and Spain played international cat-and-mouse.

Two new forces emerged to oppose Spain. Seizing upon the term, Beggars, used earlier in a derogatory manner by Margaret of Parma, the Dutch rebels formed the Wild Beggars and the Beggars of the Sea. The Wild Beggars pillaged churches and monasteries, cutting off the noses and ears of priests and monks. The Beggars of the Sea took to pirating under commission from William of Orange. William, who raised another army after a series of earlier defeats, again battled the Spanish without a single victory. He could neither control his troops nor deal with the fanatic Beggars. There existed no true unity between Catholics, Calvinists, and Protestants against Alva. The Beggars, who were nearly all ardent Calvinists, showed against the Catholics the same ferocity that the Inquisition and the Council of Blood had shown against rebels and heretics. Their captives were often given a choice between Calvinism and death. They unhesitatingly killed those who clung to the old faith, sometimes after incredible tortures. One Protestant historian wrote:

Naarden

Naarden () is a city and former municipality in the Gooi region in the province of North Holland, Netherlands. It has been part of the new municipality of Gooise Meren since 2016.

History

Naarden was granted its city rights in 1300 (the only to ...

surrendered to the Spaniards. They greeted the victorious soldiers with tables set with feasts. The soldiers ate, drank, then killed every person in the town. Don Fadrique's army later attempted to besiege Alkmaar but the rebels won by opening the dikes and routing the Spanish troops. When Don Fadrique came to Haarlem a brutal battle ensued. Haarlem was a Calvinist center that was known for its enthusiastic support of the rebels. A garrison of 4,000 troops defended the city with such intensity that Don Fadrique contemplated withdrawing. His father, Alva, threatened to disown him if he stopped the siege, so the barbarities intensified. Each army hung captives on crosses facing the enemy. The Dutch defenders taunted the Spanish besiegers by staging parodies of Catholic rituals on the cities ramparts.

William sent 3,000 men in an effort to relieve Haarlem. They were destroyed and subsequent efforts to save the city were futile. After seven months, when the city's inhabitants had been reduced to eating weeds and heather, the city surrendered (11 July 1573). Most of the 1,600 surviving defenders were put to death and 400 leading citizens were executed. Those that were spared were shown mercy only because they agreed to pay a fine of 250,000 guilders, a sizable sum even by today's standards. This was considered the last and most costly victory of Alva's regime. The Bishop of Namur estimated that in seven years, Alva had done more to harm Catholicism than Luther or Calvin had done in a generation. A new Governor of the Netherlands followed.

Division

Philip's half brother, the famous Don John, was placed in charge of the Spanish troops who, feeling cheated at not being able to pillage Zeirikzee, mutinied and began a campaign of indiscriminate plunder and violence. This " Spanish Fury" was used by William to reinforce his arguments to ally all the Netherlands' Provinces with him. The Union of Brussels was formed only to be dissolved later out of intolerance towards the religious diversity of its members. Calvinists began their wave of uncontrolled atrocities aimed at the Catholics. This divisiveness gave Spain the opportunity to send

Philip's half brother, the famous Don John, was placed in charge of the Spanish troops who, feeling cheated at not being able to pillage Zeirikzee, mutinied and began a campaign of indiscriminate plunder and violence. This " Spanish Fury" was used by William to reinforce his arguments to ally all the Netherlands' Provinces with him. The Union of Brussels was formed only to be dissolved later out of intolerance towards the religious diversity of its members. Calvinists began their wave of uncontrolled atrocities aimed at the Catholics. This divisiveness gave Spain the opportunity to send Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma

Alexander Farnese ( it, Alessandro Farnese, es, Alejandro Farnesio; 27 August 1545 – 3 December 1592) was an Italian noble and condottiero and later a general of the Spanish army, who was Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Castro from 1586 to 1592 ...

with 20,000 well-trained troops into the Netherlands. Groningen, Breda, Campen, Antwerp, and Brussels, among others, were put to siege.

Farnese, the son of Margaret of Parma, was the ablest general of Spain. In January 1579, a group of Catholic nobles formed a League for the protection of their religion and property. Later that same month Friesland, Gelderland, Groningen, Holland, Overijssel, Utrecht and Zeeland formed the United Provinces which became the Dutch Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

of today. The remaining provinces became the Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands ( Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the ...

and in the 19th century became Belgium