English Tangier on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

English Tangier was the period in Moroccan history in which the city of

In 1680, the pressure from the

In 1680, the pressure from the

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

was occupied by England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

as part of the English colonial empire

The English overseas possessions, also known as the English colonial empire, comprised a variety of overseas territories that were colonised, conquered, or otherwise acquired by the former Kingdom of England during the centuries before the Ac ...

from 1661 to 1684. Tangier had been under Portuguese control before King Charles II acquired the city as part of the dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

when he married the Portuguese '' infanta'' Catherine. The marriage treaty was an extensive renewal of the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance. It was opposed by Spain, then at war with Portugal, but clandestinely supported by France.

The English garrisoned and fortified the city against hostile but disunited Moroccan forces. The enclave was expensive to defend and fortify and offered neither commercial nor military advantage to England. When Morocco was later united under the Alaouites, the cost of maintaining the garrison against Moroccan attack greatly increased, and Parliamentary refusal to provide funds for its upkeep partly because of fears of 'Popery' and a Catholic succession under James II, forced Charles to give up possession. In 1684, the English blew up the city's harbour and defensive works that they had been constructing and evacuated the city, which was swiftly occupied and annexed by Moroccan forces.

History

Background

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

has the best natural harbour on the western end of the Strait of Gibraltar, allowing its owner to control naval access to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. Since antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, it and Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territori ...

to its east were the major commercial centres on the north-western coast of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

.

Portugal

The Portuguese started their colonial empire by taking nearby Ceuta in 1415. Years of conflict between Portugal and the Moroccans under theWattasid

The Wattasid dynasty ( ber, Iweṭṭasen; ar, الوطاسيون, ''al-waṭṭāsīyūn'') was a ruling dynasty of Morocco. Like the Marinid dynasty, its rulers were of Zenata Berber descent. The two families were related, and the Marinids ...

and Saadi dynasties followed. In 1471, the Portuguese stormed Asilah to the west and threw Tangier into such chaos that they were able to occupy it completely unopposed.

By 1657, the position had changed. The Saadi dynasty steadily lost control of the country to various warlords and finally came to an end with the death of Ahmad al-Abbas. The main warlord around Tangier was Khadir Ghaïlan (known to the English of the time as "Guyland"). He and his family had taken control of much of the Gharb, the Rif, and the other coastal areas around Tangier. He appears to have considerably increased attacks on Portuguese Tangier.

Meanwhile, after the Dila'i interlude, the Alaouites came to the forefront. Mulai al-Rashid (known as "Tafileta" by the English) took Fes in 1666 and Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

in 1669, essentially unifying all of Morocco except the ports occupied by Portugal, Spain, and England. He was supportive of restoring Muslim control over the ports, but he and the last of the Dila'ites (around Salé) still put their own pressures upon Ghaïlan.

The Treaty of the Pyrenees in November 1659 specifically pledged that Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

of France would withdraw support from Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

under the Braganzas and released Spanish troops and ships to pursue the continuing Portuguese Restoration War

The Portuguese Restoration War ( pt, Guerra da Restauração) was the war between Portugal and Spain that began with the Portuguese revolution of 1640 and ended with the Treaty of Lisbon in 1668, bringing a formal end to the Iberian Union. The ...

. Portugal, severely weakened and with little support in other countries, sought a renewal of its alliance with England to counterbalance the renewed Spanish threat to its independence.

The alliancewhich had originated in 1373had been adjusted and renewed in 1654 under Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

and was again renewed in 1660 after the English Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

. Negotiations for the marriage of Charles to Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza ( pt, Catarina de Bragança; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to King Charles II, which lasted from 21 May 1662 until his death on 6 February 1685. She ...

(originally proposed by CharlesI) had started shortly after (perhaps even before) the Restoration, and the proposed marriage was mentioned by the Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

envoys as early as June 1660. As part of the dowry, Portugal was to hand over the port of Tangier and the island of Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

(now Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the secon ...

) but it is unclear when those detailed terms were agreed upon or became publicly known. Some were widely rumoured early, certainly before the marriage treaty itself.

The Portuguese government was content to part with Tangier, though many within the country had reservations. The anchorage was not particularly safe for shipping and, exposed to the Atlantic and to destructive winds from the east, it was expensive to maintain, requiring significant improvement. Khadir Ghaïlan had mounted a major attack on the city in 1657, forcing the governor and garrison to appeal to Lisbon for assistance. Portugal, hard pressed in its war of independence from Spain and struggling against Dutch aggression in the East Indies, could not hope to maintain all of its overseas possessions without English assistance and could not afford to commit troops to the defence of Tangier while fighting Spain in the Iberian peninsula. Indeed, Portugal had even offered Tangier to France in 1648 to try to solicit support against Spain.

However, cession of Tangier to England was not popular with the general public and with many in the army. The governor of Tangier, Fernando de Meneses, refused to co-operate and had to be replaced in 1661 by the more compliant Luis de Almeida.''Routh'', p. 10.

Spain

Spain had tolerated Portuguese occupation of Tangier as part of theTreaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Em ...

and had left its Portuguese administration largely undisturbed during the Iberian Union

pt, União Ibérica

, conventional_long_name =Iberian Union

, common_name =

, year_start = 1580

, date_start = 25 August

, life_span = 1580–1640

, event_start = War of the Portuguese Succession

, event_end = Portuguese Restoration War

, ...

and even under the long-running Restoration War, lest a weakened position expose it to Moroccan reconquest. Nonetheless, Spain was strongly opposed to ''English'' possession of Tangier and insisted that the cession would be illegal. Indeed, the note presented by the Spanish ambassador in May 1661 openly threatened war.

A strongly established English naval presence at the Straits of Gibraltar posed a threat to its ports on both the Atlantic and Mediterranean and to communication between them. It also threatened communication not just with Spain's colonial empire but with the maritime links between Spain and the Habsburg's Italian possessions in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

. English fleet activities in the Mediterranean under Robert Blake and Edward Montagu between 1650 and 1659 had shown just how vulnerable Spain's shipping lanes had become. With its emphasis on its transatlantic possessions, Spain had no Mediterranean fleet and could not protect its shipping there: the presence of a hostile naval force at Tangier would make the transfer of Spanish troops from Italy to Spain for the intended war against Portugal much more difficult.

By a proclamation of 7 September 1660 (announced in Spain on 22 September), Charles had declared peace with Spain, but in the same month the Commons passed a bill annexing Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

and Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

. Both had been taken under Cromwell and both had been demanded back by Spain upon the ascension of CharlesII. There was a fear in England that the Portuguese commander at Tangier would hand the port over to Spain rather than "heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

" England or that Spain would otherwise attempt physically to prevent the handover, even if its actions fell short of war. There were further fears that Spain had enlisted Ghaïlan's assistance to attack by land while Spain attacked by sea.''Corbett'', p. 28.

Dutch Republic

TheDutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

had suffered intensely during the First Anglo-Dutch War. Although they were at peace for the moment, they were still competing intensely for trade and had no wish to see the English navy further establish the Mediterranean power it had developed under Cromwell. They ''were'' at war with the Portuguese and did not want to see the Anglo-Portuguese alliance renewed. The Dutch hoped to seize more of Portugal's overseas possessions and had equipped a fleet for that purpose in 1660. They tried, unsuccessfully, to strengthen relations with KingCharlesII by the Dutch Gift in July of the same year.

The States General also sought in negotiations from July 1660 until September 1662 to secure a treaty or pact of friendship with England, but refused to extend such a treaty to any colonies outside Europe with the sole exception of the island of Pulo Run. While that negotiation went on, Charles offered to mediate between the United Provinces and Portugal. (The Anglo-Portuguese treaty, a very short time later, required this.) His intervention resulted in the Treaty of The Hague on 6 August 1661, although it was ignored by the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

. The Company seized Cranganore

Kodungallur (; also Cranganore, Portuguese: Cranganor; formerly known as Mahodayapuram, Shingly, Vanchi, Muchiri, Muyirikkode, and Muziris) is a historically significant town situated on the banks of river Periyar on the Malabar Coast in Th ...

, Cochin

Kochi (), also known as Cochin ( ) ( the official name until 1996) is a major port city on the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea, which is a part of the Arabian Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of ...

, Nagapattinam

Nagapattinam (''nākappaṭṭinam'', previously spelt Nagapatnam or Negapatam) is a town in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Nagapattinam District. The town came to prominence during the period of Medieval ...

, and Cannanore

Kannur (), formerly known in English as Cannanore, is a city and a municipal corporation in the state of Kerala, India. It is the administrative headquarters of the Kannur district and situated north of the major port city and commercial ...

from Portugal in 1662 and 1663.

At the same time, King Charles sought the advancement of his nephew William (later WilliamIII) as Stadtholder

In the Low Countries, ''stadtholder'' ( nl, stadhouder ) was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and H ...

. Johan De Witt

Johan de Witt (; 24 September 1625 – 20 August 1672), ''lord of Zuid- en Noord-Linschoten, Snelrewaard, Hekendorp en IJsselvere'', was a Dutch statesman and a major political figure in the Dutch Republic in the mid-17th century, the F ...

, the " Grand Pensionary", was a confirmed Republican and had excluded William through the 'secret' (but widely leaked) Act of Seclusion

The Act of Seclusion was an Act of the States of Holland, required by a secret annex in the Treaty of Westminster (1654) between the United Provinces and the Commonwealth of England in which William III, Prince of Orange, was excluded from the ...

annex to the Treaty of Westminster with Cromwell. The States General was unable or unwilling to rein in the Dutch East India Company's aggressively anti-English and anti-Portuguese activities; the Republic hence had no significant influence in Restoration England, and De Witt's diplomatic failures in 1660-1661 marked the beginning of the end of the Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age ( nl, Gouden Eeuw ) was a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the era from 1588 (the birth of the Dutch Republic) to 1672 (the Rampjaar, "Disaster Year"), in which Dutch trade, science, and art and ...

. Although De Ruyter's presence in the Mediterranean necessitated caution, the English acquisition of Tangier could not be meaningfully opposed by the Dutch.

France

In France,Cardinal Mazarin

Cardinal Jules Mazarin (, also , , ; 14 July 1602 – 9 March 1661), born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino () or Mazarini, was an Italian cardinal, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Louis XIII and Louis X ...

was at the height of his powers following the formation of the League of the Rhine in 1658; the defeatwith the help of Cromwell's army and navyof the Prince of Condé and Spain at the Battle of the Dunes the same year; and the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees on 7 November 1659. Spain (then allied with English Royalists) and France (allied with Commonwealth England) made peace, and by the treaty LouisXIV was betrothed to Maria Theresa of Spain. The treaty also required France to cease direct or indirect support for Portugal. In May 1660, six months after the treaty was signed, CharlesII was restored. Mazarin realized that an alliance between Restoration England and Spain, with its extensive lands in Italy and the Netherlands, would almost surround France and leave both more powerful than he wished; he worked quickly to restore relations with Charles's court. By August, he had proposed the marriage of Philippe I, Duke of Orléans

''Monsieur'' Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (21 September 1640 – 9 June 1701), was the younger son of King Louis XIII of France and his wife, Anne of Austria. His elder brother was the "Sun King", Louis XIV. Styled Duke of Anjou from bir ...

, to Charles's sister Henrietta Anne. It is likely that he encouraged the Braganza marriage, but he died on 9 March 1661 and Louis took personal control of his government. In July 1661, Louis sent the Comte d'Estrades as his ambassador to London, and it is clear from the instructions and correspondence between them that the treaty between England and Portugal was welcomed by France. At the time, France had no significant Mediterranean or East Indies naval presence, and English possession of Tangier and Bombay posed no apparent threat. In 1656, Louis or Mazarin had proposed the cession of Tangier to France, but no agreement had been reached and the peace with Spain probably precluded any further similar proposal.

England

In 1659, Cromwell's England was allied to France by the Treaty of Paris, was allied to Portugal, was at war withSpain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, and was not a party to the Treaty of the Pyrenees. King Charles II's government in exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile ...

was, technically, allied to Spain and so pledged to resist Portugal's independence and to raise forces against France by the Treaty of Brussels

The Treaty of Brussels, also referred to as the Brussels Pact, was the founding treaty of the Western Union (WU) between 1948 and 1954, when it was amended as the Modified Brussels Treaty (MTB) and served as the founding treaty of the Western Eu ...

, the converse of the Commonwealth position. After his restoration, Charles declared peace with Spain in September 1660 but there was already speculation about a possible Portuguese marriage. There is debate as to who proposed Charles's marriage to Catherine of Braganza and when; but by a letter dated 5 or 15 June 1660, the queen regent of Portugal Luisa de Guzmán

Luisa María Francisca de Guzmán y Sandoval ( pt, Luísa Maria Francisca de Gusmão;. 13 October 1613 – 27 February 1666) was a queen consort of Portugal. She was the spouse of King John IV, the first Braganza ruler, as well as the mother o ...

requested Charles's consent to send Francisco de Mello as an ambassador extraordinary to negotiate a new treaty. According to Clarendon's account, the ambassador suggested the treaty and marriage to the lord chamberlain the Earl of Manchester

Duke of Manchester is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain, and the current senior title of the House of Montagu. It was created in 1719 for the politician Charles Montagu, 4th Earl of Manchester. Manchester Parish in Jamaica was named afte ...

, who informed the King. Charles consulted Clarendon (Lord Chancellor), Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

(Lord Treasurer), Ormonde Ormonde is a surname occurring in Portugal (mainly Azores), Brazil, England, and United States. It may refer to:

People

* Ann Ormonde (born 1935), an Irish politician

* James Ormond or Ormonde (c. 1418–1497), the illegitimate son of John Butl ...

(Lord Steward of the Household), Lord Manchester, and Sir Edward Nicholas

Sir Edward Nicholas (4 April 15931669) was an English officeholder and politician who served as Secretary of State to Charles I and Charles II. He also sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1621 and 1629. He served as secretary ...

(Secretary of State) and enquired as to Tangier of Admirals Lord Sandwich

Earl of Sandwich is a noble title in the Peerage of England, held since its creation by the House of Montagu. It is nominally associated with Sandwich, Kent. It was created in 1660 for the prominent naval commander Admiral Sir Edward Montagu. ...

and Sir John Lawson. Clarendon is vague, perhaps misleading, as to chronology. Ambassador De Mello had a private audience with Charles on 28 July 1660 (7 August 1660 NS) and, after other meetings, returned to Lisbon on 18 or 28 October 1660. The Queen Regent was pleased and made him Marquis de Sande' He returned to England on 9 February 1661 (NS) and from then until announcement of the marriage at the opening of the Cavalier Parliament

The Cavalier Parliament of England lasted from 8 May 1661 until 24 January 1679. It was the longest English Parliament, and longer than any Great British or UK Parliament to date, enduring for nearly 18 years of the quarter-century reign of C ...

on 8 or 18 May 1661 there were rumours and counter-rumours, amongst them suggested marriages to Mademoiselle d'Orleans (who had previously rejected Charles), to an unidentified 'Princess of Parma', and to Princess Maria of Nassau. Indeed, rumours continued even after that, but the treaty was signed on 23 June 1661 and witnessed by Clarendon, Southampton, Albemarle, Ormonde, Manchester, Nicholas, and Morrice

Morrice is a surname, predominantly of Scottish origin. Notable people with the name include:

* Ian Morrice, Australian CEO

*James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924), Canadian landscape painter

* Jane Morrice (born 1954), Irish politician

* Mike Morrice ...

.

English occupation

Sandwich and Portugal 1661/1662

Before the treaty with Portugal and marriage to Catherine was announced at Charles's coronation on 8 May 1661, Admiral Sir Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich was commissioned to bring Catherine over to England. The corsair fleet of Algiers was a growing problem. Montagu was instructed, by negotiation or by bombardment, to secure a treaty with Algiers not to molest English ships. He also carried instructions to seek peaceful arrangements with Tripoli, Tetuan, andSalé

Salé ( ar, سلا, salā, ; ber, ⵙⵍⴰ, sla) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the right bank of the Bou Regreg river, opposite the national capital Rabat, for which it serves as a commuter town. Founded in about 1030 by the Banu Ifran, ...

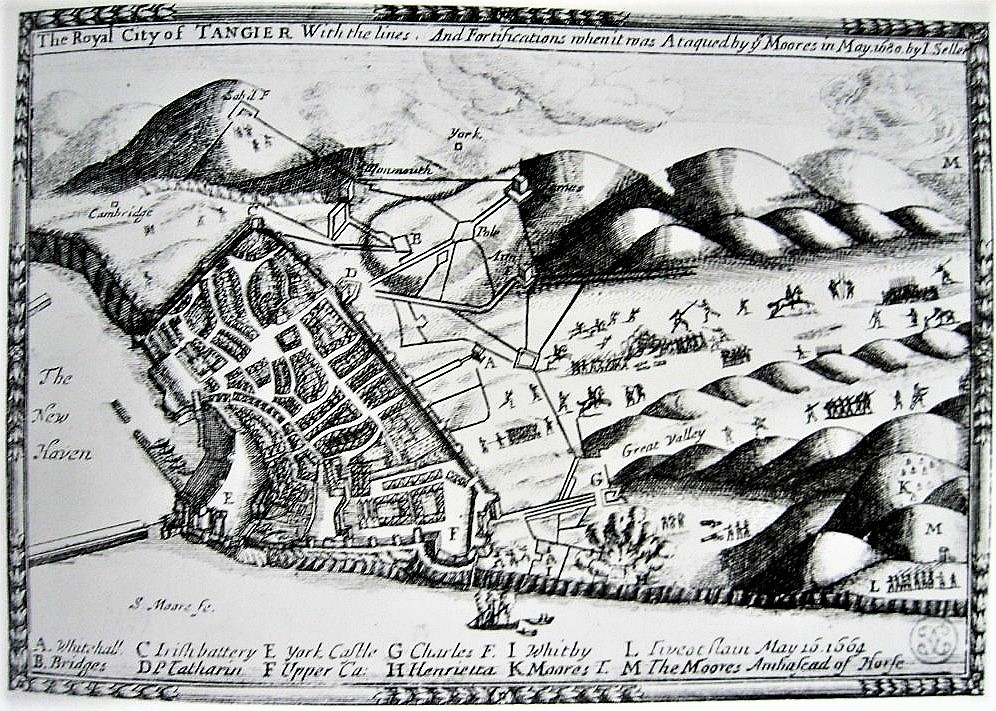

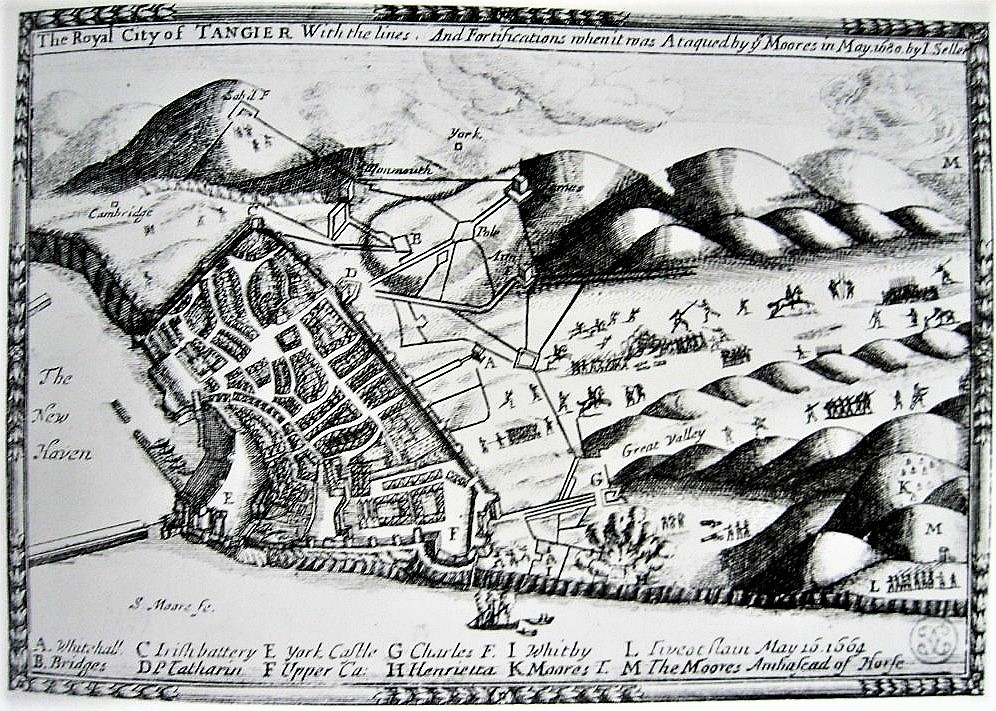

. Sandwich left London on 13 June for the fleet assembled at the Downs and from there, with John Lawson as Vice-Admiral, sailed to Algiers, where he arrived on 29 July. There was little negotiation, and a short bombardment, but weather prevented more significant action. Sandwich left Lawson to blockade Algiers, and proceeded to Lisbon, not yet in his official capacity as an Ambassador Extraordinaire, but rather to meet a second English fleet which was to take possession of Tangier. There was a perceived danger that the Spanish and Dutch would attack the Portuguese Brazil fleet and, reciprocally, Spain and the allied Dutch merchants feared that the English would attack the Spanish treasure fleet; hence there was some careful watching until those both arrived safely. The marriage, by proxy, of Charles and Catherine was notified to the Governor of Tangier (Don Luis D'Almeida) by letter from the King of Portugal on 4 September 1661. Lord Sandwich sailed back to Tangier on 3 October (arriving 10 October) taking transports for the evacuation of the Portuguese Tangier Garrison. He remained there for some three months, while awaiting the further fleet from England bringing the new Governor and troops. Still expecting trouble from Spain or the Netherlands, Lawson's squadron joined him, unsuccessful in subduing Algiers (although a storm severely damaged the harbour there the next year and enabled a peace later). During the waiting time, there was correspondence with the other Barbary ports, and with Ghaïlan, who ostensibly welcomed Sandwich. Sandwich had met Ghaïlan before, when watering the fleet during his 1657 voyage with Robert Blake in the Mediterranean. It is likely that Sandwich also used the time to obtain details of the city and its defences – Martin Beckman

Sir Martin Beckman (1634/35–1702) was a draughtsman/painter, Swedish-English colonel, chief engineer and master gunner of England.

Life

Beckman was born in Stockholm, the son of Melcher Beckman and his wife Chistiana van Benningen. He left ...

was with Sandwich's fleet at Algiers and Tangier and produced the map later seen and admired by Pepys. It was reported that Sir John Lawson and Sir Richard Stayner

Vice-Admiral Sir Richard Stayner (1625–1662) was an English naval officer who supported the Parliamentary cause during the English Civil War and the Interregnum. During the First Anglo-Dutch War he commanded the in actions at Portland (Feb ...

purchased houses in the town during this time and, perhaps, Sandwich also bought then the house he later owned.

In England, a Tangier Committee of the King's Privy Council was appointed, with its members including Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

, Secretary to the Admiralty, and Prince Rupert of the Rhine

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist cava ...

. Pepys later claimed that all Rupert did in meetings was to laugh and swear occasionally.

On 14 January 1662, the Portuguese garrison attempted a sally out into the surrounding countryside, taking about 400 head of cattle, and also capturing 35 women and girls. Unsurprisingly, the Moroccans counter-attacked and recovered the booty, killing some 51 of the Portuguese, including the Aidill (the military commander) and twelve knights, pursuing the remainder of the force to the city gates. Alarmed, the Governor (Luis de Almeida) requested assistance from Sandwich's fleet in the bay. Sandwich sent parties of seamen ashore to man the defences, under the command of Sir Richard Stayner, effectively (but not formally) taking control of the city to help protect it against attacks by Ghaïlan (supported by Spain) and, perhaps, to ensure a withdrawal by the Portuguese. By 23 January, Sandwich had three to four hundred men ashore.

Peterborough, Teviot, Bridge, FitzGerald, Belasyse and Ghaïlan 1662/1666

On 6 September 1661, King Charles had appointed Henry Mordaunt, 2nd Earl of Peterborough, as governor and captain general of all the forces in Tangier. Peterborough quite quickly raised a regiment in England, probably in large part from the Parliamentary forces which were being disbanded, but otherwise took some time over the preparations; he finally sailed for Tangier on 15 January 1662, arriving, with a considerable force, on 29 January. When Peterborough landed he found the fleet already in possession. The Tangier Garrison (his new regiment augmented by units from Flanders) disembarked on 30 January and the city keys were handed over with due ceremony. The start was far from auspicious. The available accommodation was completely insufficient for the three thousand or so troops, who had little in common (neither language nor, for the most part, religion or custom) with the Portuguese population; the money (such as was available to the new occupants) was English currency, unfamiliar to the townspeople. The basis of the Portuguese garrison had, in large part, been a militia of the men of the town and they, of course, had been driven back within the walls. Given that Portugal: had been seeking (and, latterly, expecting) to dispose of Tangier; had a major war with Spain at home; and needed to raise a very significant dowry for the marriage; it is not surprising that some neglect may have crept in but it is also clear that Peterborough was not well prepared. The list of the stores which were immediately required, even after Sandwich had provided much from the fleet, is a tacit admission of the inadequacy of those brought with the occupation force. Peterborough reported that the Portuguese, leaving, had carried off ''the very ffloers, the Windowes, and the Dores'', but since most of the inhabitants, and their possessions, were repatriated by the English fleet, that may be an exaggeration. Moreover, the idea that the Portuguese inhabitants would enrol as soldiers for the new Government is nowhere reflected in the forecast expenditure of the garrison, except in respect of a troop of horse which did, in fact, enrol. At the time when Peterborough arrived, Ghaïlan was engaged at Salé, fighting with Mohammed al-Hajj ibn Abu Bakr al-Dila'i (known to the English as "Ben Bowker") the last (as it turned out) of the Dila'ites but, with his army, he appeared close to Tangier around 22 March 1662, and Peterborough arranged parleys. Perhaps indicative of the problem with borders or limits to English possession of the city is the map of the forts around Tangier in 1680. To the East, beyond York Fort, and beyond the ominous, all-embracing, area marked as "The Moors", are the words "To Portugal Cross". It is perfectly likely that this refers to a form of padrão marking what the Portuguese considered to be the border. English occupation never came close to establishing such a distant frontier. These units were augmented later in 1662 by elements of Rutherfurd's (Scottish Royalist) Regiment and Roger Alsop's (Parliamentarian) Regiment just before Peterborough was replaced by Andrew Rutherfurd, 1st Earl of Teviot as Governor. The regiments were merged (into two in 1662) ultimately becoming a single regiment (1668), and this, the Tangier Regiment, remained in Tangier thereafter, a total of 23 years, until the port was finally evacuated in 1684. Each redoubt had four hundred men guarding the excavation site, while to the front balls of spikes, stakes and piles ofgunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

-and-stone mix, which acted as basic landmine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s, were laid.''Wreglesworth''.

Norwood, Middleton and Inchiquin 1666/1680

In 1674,William O'Brien, 2nd Earl of Inchiquin

Colonel William O'Brien, 2nd Earl of Inchiquin, PC ( – 16 January 1692), was an Irish military officer, peer and colonial administrator who served as the governor of Tangier from 1675 to 1680 and the governor of Jamaica from 1690 until his ...

took up the post of governor, in succession to the Earl of Middleton. In 1675, a garrison school was founded, led by the Rev. Dr George Mercer.

On 30 December 1676, Charles ordered a survey of the city and garrison of Tangier, which was costing about £140,000 a year to maintain. The survey showed that the total inhabitants numbered 2,225, of whom fifty were army officers, 1,231 other ranks, with 302 army wives and children. Amongst the buildings was a hospital and an army school.

On 4 June 1668, Tangier was declared a free city by charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the re ...

, with a mayor and corporation to govern it instead of the army. The charter made it equal to English towns.

Ossory, Plymouth, Sackville, Kirke and Mulai al-Rashid 1680/1683

In 1680, the pressure from the

In 1680, the pressure from the Moroccans

Moroccans (, ) are the citizens and nationals of the Kingdom of Morocco. The country's population is predominantly composed of Arabs and Berbers (Amazigh). The term also applies more broadly to any people who are of Moroccan nationality, sh ...

increased, as the Moroccan Sultan Moulay Ismail joined forces with the Chief of Fez in order to pursue a war against all foreign troops in his land. Reinforcements were needed at the Garrison, which was raised to 3,000 in number. The Royal Scots

The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment), once known as the Royal Regiment of Foot, was the oldest and most senior infantry regiment of the line of the British Army, having been raised in 1633 during the reign of Charles I of Scotland. The regime ...

, shortly followed by a further (new) foot regiment, the 2nd Tangier Regiment, (later the King's Own, 4th Regiment of Foot) raised on 13 July 1680, were sent to Tangier, reinforced by a composite King's Battalion formed from the Grenadier

A grenadier ( , ; derived from the word ''grenade'') was originally a specialist soldier who threw hand grenades in battle. The distinct combat function of the grenadier was established in the mid-17th century, when grenadiers were recruited from ...

and Coldstream Guards

The Coldstream Guards is the oldest continuously serving regular regiment in the British Army. As part of the Household Division, one of its principal roles is the protection of the monarchy; due to this, it often participates in state ceremonia ...

, the Duke of York's Regiment (disbanded in 1690) and The Holland Regiment (the later 3rd Foot) and the remnant of the old Tangier Regiment. The King's Battalion landed in July 1680, and fierce attacks were made against the Moors, who had gained a footing on the edge of the town, finally defeating them by controlled and well-aimed musket fire. The Battalion remained in Tangier until the fort was abandoned.

In 1680 the Earl of Inchiquin resigned and was replaced by Thomas Butler, 6th Earl of Ossory, who died before taking up his post.

In October 1680, Colonel Charles FitzCharles, 1st Earl of Plymouth, arrived as governor, but was taken mortally ill soon afterwards. Lt-Colonel Edward Sackville of the Coldstream Guards took over the governorship temporarily until on 28 December 1680 Colonel Piercy Kirke was appointed colonel and governor.

The garrison at Tangier had to be constantly reinforced, having cost nearly two million pounds of royal treasure, and many lives had been sacrificed in its defence. Merchant ships continued to be harassed by Barbary pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe ...

, and undefended crews were regularly captured into slavery. The so-called Popish Plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the Kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria. Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate ...

in England had intensified the dread of Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and the King's frequent request for more troops to increase the size of the garrison raised suspicions that a standing army was being retained in Tangier to ensure a Catholic succession and absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

.

In England, in the Exclusion Crisis

The Exclusion Crisis ran from 1679 until 1681 in the reign of King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland. Three Exclusion bills sought to exclude the King's brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the thrones of England, Sco ...

, the House of Commons of England

The House of Commons of England was the lower house of the Parliament of England (which incorporated Wales) from its development in the 14th century to the union of England and Scotland in 1707, when it was replaced by the House of Commons ...

petitioned the King to give his assent to the Bill of Exclusion (which had passed the Commons, but not the Lords

Lords may refer to:

* The plural of Lord

Places

*Lords Creek, a stream in New Hanover County, North Carolina

*Lord's, English Cricket Ground and home of Marylebone Cricket Club and Middlesex County Cricket Club

People

*Traci Lords (born 19 ...

) intended to disinherit the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was ...

(later James II & VII). The Earl of Shaftesbury (effectively the Prime Minister) urged Parliament to disapprove any taxes unless and until the bill was passed. The King refused to prejudice his brother's right of succession and dismissed the Exclusion Bill Parliament

The Exclusion Bill Parliament was a Parliament of England during the reign of Charles II of England, named after the long saga of the Exclusion Bill. Summoned on 24 July 1679, but prorogued by the king so that it did not assemble until 21 Octob ...

and, later, the Oxford Parliament. But he could no longer afford the cost of the colony in Tangier.

Dartmouth and evacuation 1683/1684

For some time Parliament had been concerned about the cost of maintaining the Tangier garrison. By 1680 the King had threatened to give up Tangier unless the supplies were voted for its sea defences, intended to provide a safe harbour for shipping. The fundamental problem was that in order to keep the town and harbour free from cannon fire the perimeter of the defended area had to be vastly increased. A number ofoutwork

An outwork is a minor fortification built or established outside the principal fortification limits, detached or semidetached. Outworks such as ravelins, lunettes (demilunes), flèches and caponiers to shield bastions and fortification curtain ...

s were built but the siege of 1680 showed that the Moroccans were capable of isolating and capturing these outworks by entrenchments and mining.

Although the attempt by Sultan Moulay Ismail of Morocco to seize the town had been unsuccessful, a crippling blockade by the Jaysh al-Rifi

Jaysh al-Rifi ({{Lang-ar, جيش الريف, lit=Army of the Rif), described in 18th-century correspondence with the British as 'the Army of all the People of the Rif', was the name of an influential Moroccan army corps in the 17th and the 18th ce ...

ultimately forced the English to withdraw. In 1683, Charles gave Admiral Lord Dartmouth secret orders to abandon Tangier. Dartmouth was to level the fortifications, destroy the harbour, and evacuate the troops. In August 1683 Dartmouth, as Admiral of the Fleet and governor and captain general in Tangier, sailed from Plymouth. He was accompanied by Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

, who wrote an account of the evacuation.

Once in Tangier, one of Lord Dartmouth's main concerns was the evacuation of sick soldiers "and the many families and their effects to be brought off". The hospital ship ''Unity'' sailed for England on 18 October 1683 with 114 invalid soldiers and 104 women and children, alongside HMS ''Diamond''. HMS ''Diamond'' arrived at The Downs on 14 December 1683. Dartmouth was also able to purchase the release of many English prisoners from Ismail's bagnio

Bagnio is a loan word into several languages (from it, bagno). In English, French, and so on, it has developed varying meanings: typically a brothel, bath-house, or prison for slaves.

In reference to the Ottoman Empire

The origin of this sens ...

, including several officers and about 40 men, some of whom had spent 10 years in the hands of the Moroccans.

All the forts and walls were mined for last-minute destruction. On 5 February 1684 Tangier was officially evacuated, leaving the town in ruins. Thereafter Kirke's Regiment (i.e., the Tangier Regiment) returned to England. The main force of 2,830 officers and men and 361 wives and children finally completed the demolition of the harbour wall and fortifications, and evacuated the garrison during the early months of 1684. The 2nd Tangier Regiment left late in the second week of February for Plymouth with some six hundred men and thirty wives and children. The Earl of Dumbarton's regiment (The Royal Scots) went into quarters at Rochester

Rochester may refer to:

Places Australia

* Rochester, Victoria

Canada

* Rochester, Alberta

United Kingdom

*Rochester, Kent

** City of Rochester-upon-Medway (1982–1998), district council area

** History of Rochester, Kent

** HM Prison ...

, and Trelawney's (Second Tangier) Regiment to Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

.

Aftermath

Some of the departing soldiers were to be rewarded with large land grants in the newly acquiredProvince of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

. Thomas Dongan, 2nd Earl of Limerick

Thomas Dongan, (pronounced "Dungan") 2nd Earl of Limerick (1634 – 14 December 1715), was a member of the Irish Parliament, Royalist military officer during the English Civil War, and Governor of the Province of New York. He is noted for ha ...

, a lieutenant-governor of Tangier, became New York provincial governor and William "Tangier" Smith

William "Tangier" Smith (February 2, 1655 – February 18, 1705) was a governor of Tangier, on the coast of Morocco, and an early settler of New York who owned more than of Atlantic Ocean waterfront property in central Long Island in New York S ...

, the last mayor of Tangier, obtained 50 miles of Atlantic oceanfront property on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

.

The mole

The English planned to improve the harbour by building a mole, which would reach long and cost £340,000 before its demolition. The improved harbour was to be long, deep at low tide, and capable of keeping out the roughest of seas. Work began on the fortified harbour at the end of November, 1662, and work on the Mole in August, 1663. The work continued for some years under a succession of governors. With an improved harbour the town would have played the same role thatGibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

later played in British naval strategy.Enid M. G. Routh – Tangier: England's lost Atlantic outpost, 1912; Martin Malcolm Elbl, "(Re)claiming Walls: The Fortified Médina of Tangier under Portuguese Rule (1471–1661) and as a Modern Heritage Artefact," ''Portuguese Studies Review'' 15 (1–2) (2007; publ. 2009): 103–192.

Governors

See also

* List of governors of Tangier * George Elliott, surgeon *Roger Elliott

Major General Roger Elliott ( 1665 – 16 May 1714

)

was one of the earliest British Governors of Gibraltar. A member of the Eliot family, his son Granville Elliott became the first Count Elliott and his nephew George Augustus Eliott als ...

* Alexander Spotswood

* Tangier Protocol

The Tangier Protocol (formally the Convention regarding the Organisation of the Statute of the Tangier Zone) was an agreement signed between France, Spain, and the United Kingdom by which the city of Tangier in Morocco became the Tangier Interna ...

* Tangier Garrison

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * as reproduced at * * * . * * * * * ''Venetian Papers'' * URL is preview location only. * * . URL is preview location only. * . URL is preview location only. {{Authority control History of TangierTangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

Former colonies in Africa

Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

17th century in Morocco

1661 establishments in Africa

1684 disestablishments in Africa

1661 establishments in the British Empire

1684 disestablishments in the British Empire

1660s in the British Empire

1670s in the British Empire

1680s in the British Empire