Edward P. Ney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Purdy Ney (October 28, 1920 – July 9, 1996) was an American physicist who made major contributions to cosmic ray research,

Although early plastic balloons performed spectacularly in a few cases, there were dangerous mishaps during launch and many unexplained failures in flight. Ney realized that this unreliability was due to inadequate engineering and a fundamental lack of understanding of balloon physics. In response, he collaborated with Critchfield and Winckler to carry out a project entitled "Research and Development in the Field of High Altitude Plastic Balloons", which was sponsored by the US Army, Navy, and Air Force under a contract with the

Although early plastic balloons performed spectacularly in a few cases, there were dangerous mishaps during launch and many unexplained failures in flight. Ney realized that this unreliability was due to inadequate engineering and a fundamental lack of understanding of balloon physics. In response, he collaborated with Critchfield and Winckler to carry out a project entitled "Research and Development in the Field of High Altitude Plastic Balloons", which was sponsored by the US Army, Navy, and Air Force under a contract with the

Ney's studies of the corona piqued his curiosity about other sources of dim light within the Solar System. Consequently, Ney and Huch developed reliable cameras whose low

Ney's studies of the corona piqued his curiosity about other sources of dim light within the Solar System. Consequently, Ney and Huch developed reliable cameras whose low

atmospheric physics

Within the atmospheric sciences, atmospheric physics is the application of physics to the study of the atmosphere. Atmospheric physicists attempt to model Earth's atmosphere and the atmospheres of the other planets using fluid flow equations, rad ...

, heliophysics

Heliophysics (from the prefix "wikt:helio-, helio", from Attic Greek ''hḗlios'', meaning Sun, and the noun "physics": the science of matter and energy and their interactions) is the physics of the Sun and its connection with the Solar System. ...

, and infrared astronomy

Infrared astronomy is a sub-discipline of astronomy which specializes in the astronomical observation, observation and analysis of astronomical objects using infrared (IR) radiation. The wavelength of infrared light ranges from 0.75 to 300 microm ...

. He was a discoverer of cosmic ray heavy nuclei and of solar proton events. He pioneered the use of high-altitude balloons for scientific investigations and helped to develop procedures and equipment that underlie modern scientific ballooning. He was one of the first researchers to put experiments aboard spacecraft.

In 1963, Ney became one of the first infrared astronomers. He founded O'Brien Observatory, where he and his colleagues discovered that certain stars are surrounded by grains of carbon and silicate minerals

Silicate minerals are rock-forming minerals made up of silicate groups. They are the largest and most important class of minerals and make up approximately 90 percent of Earth's crust.

In mineralogy, the crystalline forms of silica (silicon dio ...

and established that these grains, from which planets are formed, are ubiquitous in circumstellar winds and regions of star formation.

Early life

Ney's father, Otto Fred Ney and mother, Jessamine Purdy Ney, lived inWaukon, Iowa

Waukon is a city in Makee Township, Allamakee County, Iowa, Makee Township,

Allamakee County, Iowa, Allamakee County, Iowa, United States, and the county seat of Allamakee County. The population was 3,827 at the time of the United States Census ...

. However, in October 1920, his mother went to Minneapolis, Minnesota

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

, where Ney was delivered by Caesarean section

Caesarean section, also known as C-section, cesarean, or caesarean delivery, is the Surgery, surgical procedure by which one or more babies are Childbirth, delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen. It is often performed because va ...

. After elementary school, he attended Waukon High School, where he developed an interest in science and mathematics that was encouraged by Coach Howard B. Moffitt, who taught several of his courses and later became an administrator at the University of Iowa

The University of Iowa (U of I, UIowa, or Iowa) is a public university, public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized int ...

.

Career

In 1938, Ney began undergraduate studies at theUniversity of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities (historically known as University of Minnesota) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint ...

, where he became acquainted with Professor Alfred O. C. Nier, who was an expert in mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a ''mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is used ...

. Soon, Nier recruited him to work in the spectroscopy laboratory for 35 cents per hour. In February 1940, Nier prepared a tiny but pure sample of Uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

, which he mailed to Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, where John R. Dunning and his team proved that this isotope

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their Atomic nucleus, nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemica ...

was responsible for nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

, rather than the more abundant Uranium-238

Uranium-238 ( or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However, it i ...

. This finding was a crucial step in the development of the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

. That summer, Ney and Robert Thompson prepared a larger sample of Uranium-235, which provided material for further important tests. Later, he helped Nier design and test mass spectrographs that were replicated for extensive use in the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

.

Graduate studies in Virginia

In June 1942, after graduating with a B.S. degree in physics, Ney married June Felsing. They had four children: Judy, John, Arthur, and William. That year, Ney took his bride and two of Nier's mass spectrographs toCharlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city (United States), independent city in Virginia, United States. It is the county seat, seat of government of Albemarle County, Virginia, Albemarle County, which surrounds the ...

, where he began graduate studies with Jesse Beams

Jesse Wakefield Beams (December 25, 1898 in Belle Plaine, Kansas – July 23, 1977) was an American physicist at the University of Virginia. He was particularly known for his role in the development of the ultracentrifuge.

Biography

Beams ...

at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

. Ney brought experience and equipment that contributed significantly to Beams's wartime project to develop gas centrifuges for separation of uranium isotopes.

With Beams as his thesis advisor, Ney measured the self-diffusion coefficient of uranium hexafluoride

Uranium hexafluoride, sometimes called hex, is the inorganic compound with the formula . Uranium hexafluoride is a volatile, white solid that is used in enriching uranium for nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons.

Preparation

Uranium dioxide is co ...

. At the time, his results were classified

Classified may refer to:

General

*Classified information, material that a government body deems to be sensitive

*Classified advertising or "classifieds"

Music

*Classified (rapper) (born 1977), Canadian rapper

* The Classified, a 1980s American ro ...

, but in 1947, they were published in the Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal. The journal was established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the Ame ...

. In 1946, Ney received his Ph.D. in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

and became an assistant professor at the University of Virginia. With Beams and Leland Swoddy, he began an underground cosmic ray

Cosmic rays or astroparticles are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the ...

experiment in Endless Caverns near New Market, Virginia

New Market is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States. Founded as a small crossroads trading town in the Shenandoah Valley, it has a population of 2,155 as of the most recent 2020 U.S. census. The north–south U.S. 11 and the east� ...

.

Return to Minnesota

John T. Tate was an influential professor of physics at theUniversity of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities (historically known as University of Minnesota) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint ...

, who was Nier's mentor and editor of the ''Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal. The journal was established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the Ame ...

''. After the war, he recognized the research potential of large plastic balloons, which had been invented by Jean Piccard and were being manufactured at the General Mills

General Mills, Inc. is an American multinational corporation, multinational manufacturer and marketer of branded ultra-processed consumer foods sold through retail stores. Founded on the banks of the Mississippi River at Saint Anthony Falls in ...

Laboratories in the Como neighborhood of Minneapolis. Here, Otto C. Winzen used polyethylene to make balloons whose performance at high altitudes was better than the cellophane ones developed by Piccard. In 1947, because of Ney's interest in cosmic rays, Tate offered him a position as assistant professor, which was immediately accepted. Except for a sabbatical and two brief leaves of absence, Ney spent the rest of his life at Minnesota.

Discovery of heavy cosmic ray nuclei

Back in Minneapolis, Ney metFrank Oppenheimer

Frank Friedman Oppenheimer (14 August 1912 – 3 February 1985) was an American particle physicist, cattle rancher, professor of physics at the University of Colorado, and the founder of the Exploratorium in San Francisco.

The younger brother o ...

and Edward J. Lofgren, who had both arrived about a year earlier. In response to Tate's initiative, these three decided to use balloons to study primary cosmic rays at the top of the atmosphere. At first, they focused on developing cloud chamber

A cloud chamber, also known as a Wilson chamber, is a particle detector used for visualizing the passage of ionizing radiation.

A cloud chamber consists of a sealed environment containing a supersaturated vapor of water or alcohol. An energetic ...

s small enough to fly on balloons, but soon realized that nuclear emulsion A nuclear emulsion plate is a type of particle detector first used in nuclear and particle physics experiments in the early decades of the 20th century. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1728791/files/vol6-issue5-p083-e.pdf''The Study of Elementary Partic ...

s offer a more portable way to detect energetic particles. To take charge of emulsion work, they enlisted a graduate student, Phyllis S. Freier, as the fourth member of their group. Later, she became a renowned professor. In 1948, the Minnesota group collaborated with Bernard Peters and Helmut L. Bradt, of the University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

, to launch a balloon flight carrying a cloud chamber and emulsions. This flight gave evidence for heavy nuclei among the cosmic rays. More specifically, the researchers discovered that, in addition to Hydrogen nuclei (protons

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' ( elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an electron (the pro ...

), primary cosmic rays contain substantial numbers of fast moving nuclei of elements from helium

Helium (from ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, non-toxic, inert gas, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. Its boiling point is ...

to iron.

In ordinary matter, atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

s of these elements consist of a nucleus

Nucleus (: nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucleu ...

surrounded by a cloud of electrons, but when the nuclei arrive as cosmic rays, they are devoid of electrons, because of collisions with atoms in interstellar matter. In both emulsions and cloud chambers, these "stripped" heavy nuclei leave an unmistakable track, which is much denser and "hairier" than that of protons, and whose characteristics make it possible to determine their atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of pro ...

. In further flights, the group showed that the abundances of elements in cosmic rays are similar to those found on Earth and in stars. These results had a major impact, for they showed that studies of cosmic radiation could play a significant role in astrophysics

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline, James Keeler, said, astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the ...

.

Shortly after these discoveries, Lofgren left for California to build the Bevatron

The Bevatron was a particle accelerator — specifically, a Weak focusing, weak-focusing proton synchrotron — located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, U.S., which began operations in 1954. The antiproton was discovered there in ...

. In 1949, Oppenheimer was forced to resign from the Minnesota faculty, because he had concealed his prewar membership in the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

. That year, John R. Winckler joined Minnesota's cosmic ray group.

In 1950, with the aid of a cloud chamber that contained lead plates, Ney, together with Charles Critchfield and graduate student Sophie Oleksa, searched for primary cosmic ray electrons

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

. They did not find them, but in 1960, James Earl, who joined the Minnesota group in 1958, used similar apparatus to discover a small primary electron component.

During the decade from 1950 to 1960, Ney's cosmic ray research shifted away from cloud chambers toward emulsions. However, his graduate students used counter controlled cloud chambers to make significant advances in electronic instrumentation for the detection and analysis of cosmic rays. Specifically, in 1954, John Linsley used a cloud chamber triggered by a cherenkov detector

A Cherenkov detector (pronunciation: /tʃɛrɛnˈkɔv/; Russian: Черенко́в) is a type particle detector designed to detect and identify particles by the Cherenkov Radiation produced when a charged particle travels through the medium of th ...

to study the charge distribution of heavy nuclei, and in 1955, Frank McDonald used one triggered by a scintillation counter

A scintillation counter is an instrument for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation by using the Electron excitation, excitation effect of incident radiation on a Scintillation (physics), scintillating material, and detecting the resultant li ...

for a similar purpose. Later, McDonald combined these two electronic detectors into a balloon instrument that served as a prototype for devices carried on many spacecraft.

Balloon technology

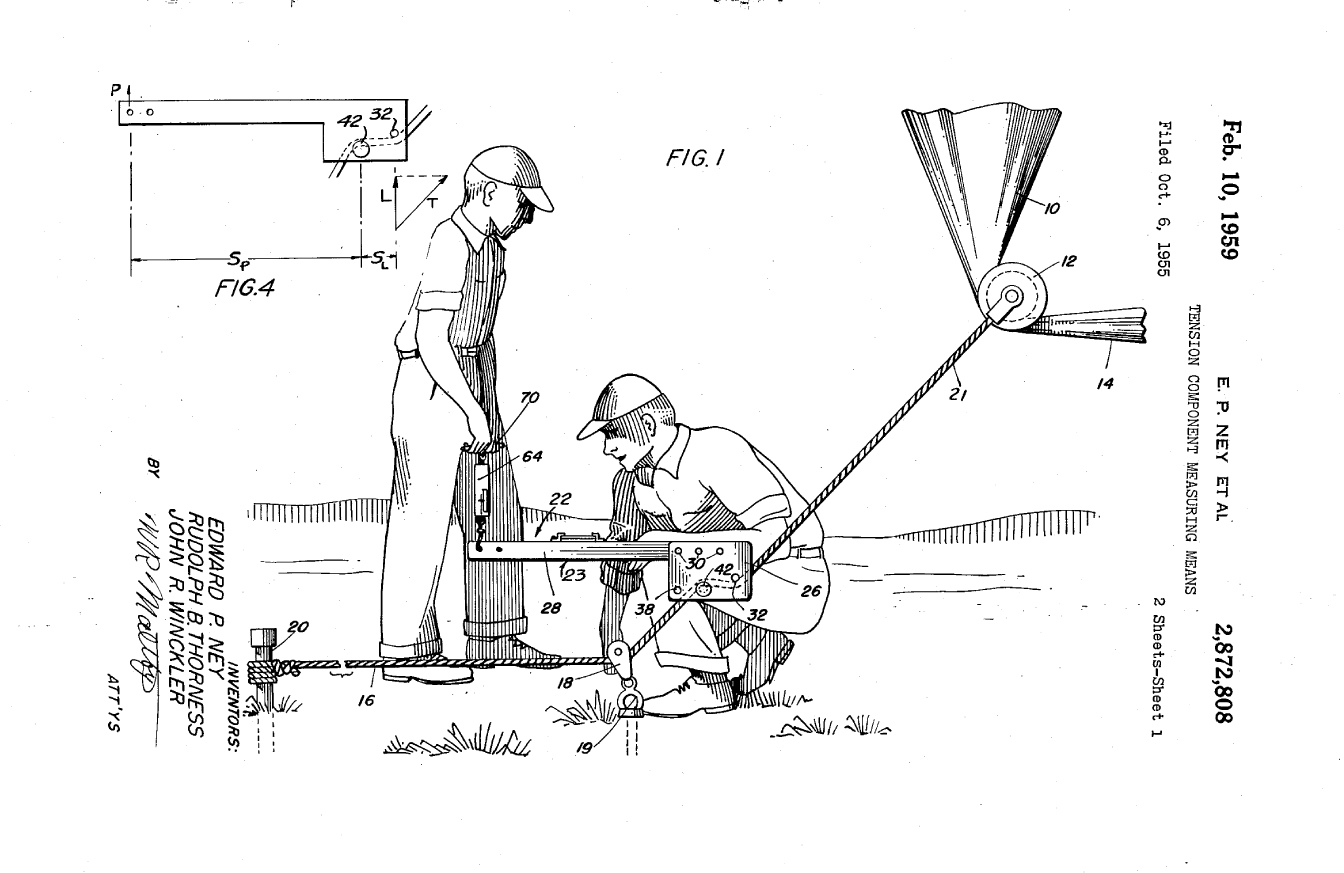

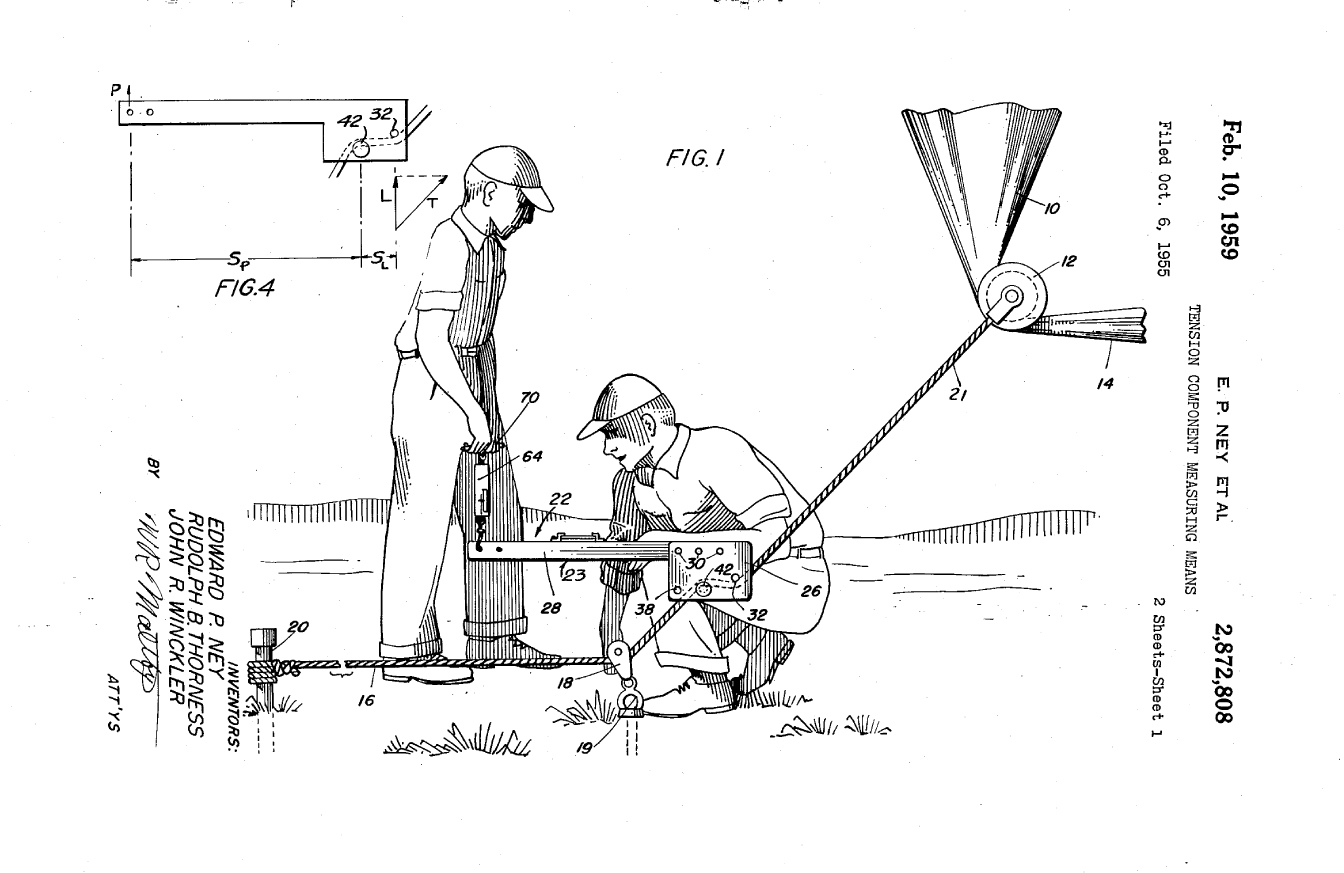

Although early plastic balloons performed spectacularly in a few cases, there were dangerous mishaps during launch and many unexplained failures in flight. Ney realized that this unreliability was due to inadequate engineering and a fundamental lack of understanding of balloon physics. In response, he collaborated with Critchfield and Winckler to carry out a project entitled "Research and Development in the Field of High Altitude Plastic Balloons", which was sponsored by the US Army, Navy, and Air Force under a contract with the

Although early plastic balloons performed spectacularly in a few cases, there were dangerous mishaps during launch and many unexplained failures in flight. Ney realized that this unreliability was due to inadequate engineering and a fundamental lack of understanding of balloon physics. In response, he collaborated with Critchfield and Winckler to carry out a project entitled "Research and Development in the Field of High Altitude Plastic Balloons", which was sponsored by the US Army, Navy, and Air Force under a contract with the Office of Naval Research

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is an organization within the United States Department of the Navy responsible for the science and technology programs of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. Established by Congress in 1946, its mission is to plan ...

, Nonr-710 (01), which was in force from December 1951 until August 1956.

During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, the United States sponsored several heavily funded and top secret attempts to carry out surveillance of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

by means of balloon overflights. These included: Project Mogul, Project Moby Dick, and Project Genetrix. In July 1958, responding to the disappointing results of these efforts and to the deployment of the Lockheed U-2

The Lockheed U-2, nicknamed the "''Dragon Lady''", is an American single-engine, high–altitude reconnaissance aircraft operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) since the 1950s. Designed for all- ...

, President Eisenhower ordered an end to balloon surveillance. Because the secret programs made use of information from the Minnesota balloon project, it too was secret, but all its materials were declassified in 1958.

While the project was active, Ney and his coworkers carried out 313 major or experimental balloon flights, published 16 technical reports, and patented approximately 20 inventions. The final report lists 62 major innovations and achievements. The innovations include the duct appendix, the natural shape balloon, the Minnesota launch system, and the tetroon balloon design. The last achievement listed was the post-project flight of a mylar

BoPET (biaxially oriented polyethylene terephthalate) is a polyester film made from stretched polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and is used for its high tensile strength, chemical stability, dimensional stability, transparency reflectivity, an ...

tetroon on September 7, 1956, which reached a maximum height of 145,000 feet (44,000 m) over Minneapolis. At the time, this was a record altitude for balloons, and there was considerable press coverage of the flight. Most of the project's balloons were launched at the University of Minnesota Airport in New Brighton, Minnesota

New Brighton ( ) is a city in Ramsey County, Minnesota, United States. It is a suburb of the Twin Cities. The population was 23,454 at the 2020 census.

History

In the mid 18th century, Mdewakanton Dakota tribes lived in the vicinity of New ...

. They were among more than 1000 flights launched here from 1948 until the airport was devastated by a tornado on May 6, 1965.

Key personnel of the project were: Raymond W. Maas and William F. Huch, who provided engineering expertise, Rudolph B. Thorness, who was in charge of the physics machine shop, Robert L. Howard, who ran the electronics shop, and Leland S. Bohl, who worked on the project while earning his Ph.D. under Ney. Many of their names appear as authors not only of patents and technical reports, but also of scientific publications.

In spite of its secrecy, many of the project's balloons carried instruments for open scientific research. For example, from January 20, 1953, until February 4, 1953, with Winzen Research, Inc, the project launched 13 flights at Pyote Air Force Base in Texas. Several of these carried packages for cosmic ray research, one of which was designated as "ballast". These were Skyhook flights, which is the generic term used by the Office of Naval Research to designate balloon flights whose primary objectives were scientific, rather than military. Some milestones of more than 1500 Skyhook flights are: the first Skyhook launch (1947), the first shipboard launch (1949), the Rockoon

A rockoon (from ''rocket'' and ''balloon'') is a sounding rocket that, rather than being lit immediately while still on the ground, is first carried into the upper atmosphere by a gas-filled balloon, then separated from the balloon and ignited. ...

program (1952), the tetroon record flight of September 1956, Stratoscope (1957 - 1971), and Skyhook Churchill (1959 - 1976).

In 1960, the National Center for Atmospheric Research

The US National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR ) is a US federally funded research and development center (FFRDC) managed by the nonprofit University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) and funded by the National Science Foundat ...

was established. On October 17, 1961, its panel on scientific balloons met to select a permanent launch site for balloon operations. Members of this panel, whose chairman was Verner E. Suomi, were Ney, Charles B. Moore, Alvin Howell, James K. Angell, J. Allen Hynek

Josef Allen Hynek (May 1, 1910 – April 27, 1986) was an American astronomer, professor, and ufologist. He is perhaps best remembered for his UFO research. Hynek acted as scientific advisor to UFO studies undertaken by the U.S. Air Force un ...

, and Martin Schwarzschild

Martin Schwarzschild (May 31, 1912 – April 10, 1997) was a German-American astrophysicist. The Schwarzschild criterion, for the stability of stellar gas against convention, is named after him.

Biography

Schwarzschild was born in Potsdam ...

, who was the prime mover behind Stratoscope. They chose Palestine, Texas, where the National Scientific Balloon Facility (NSBF) was created in 1962. Since then, thousands of balloons have been launched there, and it has served as the base for flight expeditions all over the world.

The Minnesota balloon project pioneered procedures and equipment used in Skyhook, NSBF, and the crewed flights of Projects Stratolab and Manhigh. These include launch methods, design of reliable balloons, knowledge of atmospheric

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosphere ...

structure, and reliable instrumentation for flight control and tracking.

Atmospheric physics

During the balloon project, winds and temperatures in the atmosphere were prime subjects for investigation, for they have a critical impact on balloon performance. To map out upper level winds, Professor Homer T. Mantis used "down cameras", which photographed features on the ground. Ney was interested in studying variations of air temperature with altitude. To measure them, he put thermistors and wire thermometers on many flights. With the aid of standardradiosonde

A radiosonde is a battery-powered telemetry instrument carried into the atmosphere usually by a weather balloon that measures various atmospheric parameters and transmits them by radio to a ground receiver. Modern radiosondes measure or calculat ...

equipment, Ney's student, John L. Gergen, carried out 380 radiation temperature soundings in parallel with the balloon project. With Leland Bohl, and Suomi, he invented and patented the "black ball", which is an instrument that responds not to air temperature, but to thermal radiation

Thermal radiation is electromagnetic radiation emitted by the thermal motion of particles in matter. All matter with a temperature greater than absolute zero emits thermal radiation. The emission of energy arises from a combination of electro ...

in the atmosphere.

After 1956, the Office of Naval Research continued to support, under Nonr-710 (22), Minnesota's research in atmospheric physics

Within the atmospheric sciences, atmospheric physics is the application of physics to the study of the atmosphere. Atmospheric physicists attempt to model Earth's atmosphere and the atmospheres of the other planets using fluid flow equations, rad ...

. While this grant was in force, and earlier during the balloon project, Ney's students made major contributions, which he summarized as follows:

John Kroening studied atmospheric small ions, invented a chemiluminescent ozone detector, and did a seminal study of atmospheric ozone. John Gergen designed the "black ball" and studied atmospheric radiation balance, culminating in a national series of radiation soundings in which a majority of the weather bureau stations took part. Jim Rosen studied aerosols with an optical coincidence counter, which was so good it still has not been improved; he was the first to discover thin laminar layers of dust in the stratosphere and to identify the source as volcanic eruptions. Ted Pepin participated in photographic observations from balloon platforms, and has subsequently carried this interest further with optical observations of the Earth's limb from satellites.

Solar energetic particles and the IGY

The International Geophysical Year (IGY) was an international scientific initiative that lasted from July 1, 1957, to December 31, 1958. Because its agenda included studies of cosmic rays, Ney served on the IGY's US National Committee - Technical Panel on Cosmic Rays. Other members of the panel were: Scott E. Forbush (chairman), Serge A. Korff, H. Victor Neher, J. A. Simpson, S. F. Singer and J. A. Van Allen. With Winckler and Freier, Ney proposed to keep balloons aloft (nearly) continuously to monitor the intensity of cosmic rays during the period of maximumsolar activity

Solar phenomena are natural phenomena which occur within the Stellar atmosphere, atmosphere of the Sun. They take many forms, including solar wind, Solar radio emission, radio wave flux, solar flares, coronal mass ejections, Stellar corona#Coron ...

that coincided with the IGY. When this ambitious proposal was funded, Freier and Ney took responsibility for emulsion packs that went on every flight, and Winckler designed a payload that combined an ionization chamber

The ionization chamber is the simplest type of gaseous ionisation detector, and is widely used for the detection and measurement of many types of ionizing radiation, including X-rays, gamma rays, alpha particles and beta particles. Conventionall ...

with a geiger counter

A Geiger counter (, ; also known as a Geiger–Müller counter or G-M counter) is an electronic instrument for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation with the use of a Geiger–Müller tube. It is widely used in applications such as radiat ...

.

On the first day of the IGY, this scheme paid off, when Winckler and his students, Laurence E. Peterson, Roger Arnoldy and Robert Hoffman, observed X rays whose intensity followed temporal variations of an aurora

An aurora ( aurorae or auroras),

also commonly known as the northern lights (aurora borealis) or southern lights (aurora australis), is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly observed in high-latitude regions (around the Arc ...

over Minneapolis. A few weeks later, Winckler and Peterson observed a brief burst of gamma ray

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from high energy interactions like the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei or astronomical events like solar flares. It consists o ...

s from a Solar Flare.

During the balloon project, Ney's research on cosmic rays became less intense, but he continued to work with Freier and guided student work in the field. He became more active, in anticipation of IGY, when Peter Fowler came to Minnesota in 1956/57. Fowler, Freier and Ney measured the intensity of Helium nuclei as a function of energy. They found that, at high energies, the intensity exhibited a steep decrease with increasing energy, but at lower energies, it peaked and then decreased at even lower energies. Because the peak intensity varied within the solar cycle

The Solar cycle, also known as the solar magnetic activity cycle, sunspot cycle, or Schwabe cycle, is a periodic 11-year change in the Sun's activity measured in terms of Modern Maximum, variations in the number of observed sunspots on the Sun ...

, these measurements were an early observation of the solar modulation of low-energy galactic cosmic rays.

After Fowler had returned to Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

, Freier, Ney and Winckler observed a very high intensity of particles on March 26, 1958, which examination of the emulsions proved were mostly low-energy protons, and which were associated with a solar flare

A solar flare is a relatively intense, localized emission of electromagnetic radiation in the Sun's atmosphere. Flares occur in active regions and are often, but not always, accompanied by coronal mass ejections, solar particle events, and ot ...

. This was surprising, because the Earth's magnetic field would normally have prevented these particles from reaching Minnesota. Consequently, the team concluded that a geomagnetic storm

A geomagnetic storm, also known as a magnetic storm, is a temporary disturbance of the Earth's magnetosphere that is driven by interactions between the magnetosphere and large-scale transient Plasma (physics), plasma and magnetic field structur ...

, which was underway during the event, had distorted the field enough to admit protons. Later, these influxes of solar energetic particles

Solar energetic particles (SEP), formerly known as solar cosmic rays, are high-energy, charged particles originating in the solar atmosphere and solar wind. They consist of protons, electrons and heavy ions with energies ranging from a few tens ...

, whose discovery was an important achievement of IGY, became designated as solar proton events. Along with geomagnetic storms, they are important phenomena of space weather

Space weather is a branch of space physics and aeronomy, or heliophysics, concerned with the varying conditions within the Solar System and its heliosphere. This includes the effects of the solar wind, especially on the Earth's magnetosphere, ion ...

, and their intensive study continues in an effort to understand the propagation of charged particles in interplanetary space.

After the IGY ended, Ney's interest in cosmic rays began to diminish, but in 1959, he wrote an often cited paper ''Cosmic Rays and the Weather'', in which "he was probably the first person to discuss climatological effects of cosmic rays".

Dim Light

In 1959, Ney and his colleague Paul J. Kellogg developed a theory of thesolar corona

In astronomy, a corona (: coronas or coronae) is the outermost layer of a star's Stellar atmosphere, atmosphere. It is a hot but relatively luminosity, dim region of Plasma (physics), plasma populated by intermittent coronal structures such as so ...

based on the idea that some of its light is synchrotron radiation

Synchrotron radiation (also known as magnetobremsstrahlung) is the electromagnetic radiation emitted when relativistic charged particles are subject to an acceleration perpendicular to their velocity (). It is produced artificially in some types ...

emitted by energetic electrons spiraling in solar magnetic fields. This theory predicted that the polarization of coronal light would exhibit a component perpendicular to that arising from Thomson scattering

Thomson scattering is the elastic scattering of electromagnetic radiation by a free charged particle, as described by classical electromagnetism. It is the low-energy limit of Compton scattering: the particle's kinetic energy and photon frequency ...

of sunlight, which had been widely considered to be the source of coronal luminosity. To test this theory, Ney developed an "eclipse polarimeter", to measure the intensity and direction of coronal polarization during a total solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs approximately every six months, during the eclipse season i ...

. Ney and his colleagues decided to perform these measurements during the eclipse of October 2, 1959, which was visible from North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, where there was only a small chance that clouds over the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

would spoil the observations. In July, Ney went to French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

to set up logistical support for an expedition. Here, a military truck, in which he was scouting locations to view the eclipse, overturned, and Ney suffered seven broken ribs, a broken collarbone and a broken leg. By October, Ney had recovered enough to return to Africa, where he and his colleagues deployed three polarimeters along the track of the total eclipse. One of these was clouded over, but the other two returned good data. The results disproved the theory of Kellogg and Ney.

To confirm and extend these observations, Ney organized an expedition to The Forks, Maine

The Forks is a plantation in Somerset County, Maine, United States. The population was 48 at the 2020 census.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the plantation has a total area of , of which is land and (4.46%) is water. ...

and Senneterre, Quebec, where he set up two polarimeters to measure the corona during the eclipse of July 20, 1963. In coordination with these measurements, two balloons were launched into the path of totality with cameras to record the zodiacal light

The zodiacal light (also called false dawn when seen before sunrise) is a faint glow of diffuse sunlight scattered by interplanetary dust. Brighter around the Sun, it appears in a particularly dark night sky to extend from the Sun's direct ...

. Zodiacal cameras were also launched in Australia by V. D. Hopper and J. G. Sparrow, and astronaut Scott Carpenter

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (May 1, 1925 – October 10, 2013) was an American naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut. He was one of the Mercury Seven astronauts selected for NASA's Project Mercury ...

took photographs of the corona from an aircraft at 40,000 feet over Canada.

Ney's studies of the corona piqued his curiosity about other sources of dim light within the Solar System. Consequently, Ney and Huch developed reliable cameras whose low

Ney's studies of the corona piqued his curiosity about other sources of dim light within the Solar System. Consequently, Ney and Huch developed reliable cameras whose low F-number

An f-number is a measure of the light-gathering ability of an optical system such as a camera lens. It is calculated by dividing the system's focal length by the diameter of the entrance pupil ("clear aperture").Smith, Warren ''Modern Optical ...

enhanced their ability to record dim light, but sacrificed picture sharpness. This compromise proved to be appropriate for the dim and diffuse zodiacal light

The zodiacal light (also called false dawn when seen before sunrise) is a faint glow of diffuse sunlight scattered by interplanetary dust. Brighter around the Sun, it appears in a particularly dark night sky to extend from the Sun's direct ...

and airglow

Airglow is a faint emission of light by a planetary atmosphere. In the case of Earth's atmosphere, this optical phenomenon causes the night sky never to be completely dark, even after the effects of starlight and diffuse sky radiation, diffuse ...

. On May 15, 1963, aboard '' Faith 7'', one of Ney's cameras was operated in space by Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper

Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr. (March 6, 1927 – October 4, 2004) was an American aerospace engineer, test pilot, United States Air Force Aviator, pilot, and the youngest of the Mercury Seven, seven original astronauts in Project Mercury, the f ...

. According to Ney's student John E. Naugle, NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

's Associate Administrator for Space Science and Applications, one of its images was: ".... the first photograph of the night airglow taken from above." NASA designated Ney's experiment as "S-1", which means that it was the first scientific experiment conducted on a crewed space flight. Later, aboard Geminis, 5, 9, 10, and 11, astronauts photographed the Zodiacal Light

The zodiacal light (also called false dawn when seen before sunrise) is a faint glow of diffuse sunlight scattered by interplanetary dust. Brighter around the Sun, it appears in a particularly dark night sky to extend from the Sun's direct ...

and the gegenschein

Gegenschein (; ; ) or counterglow is a faintly bright spot in the night sky centered at the antisolar point. The backscatter of sunlight by interplanetary dust causes this optical phenomenon, being a zodiacal light and part of its zodiacal light ...

, which had been obscured in the Mercury missions by nightglow.

Ney followed up his zodiacal experiments on crewed space missions by putting instruments aboard the Orbiting Solar Observatory

The Orbiting Solar Observatory (abbreviated OSO) Program was the name of a series of American space telescopes primarily intended to study the Sun, though they also included important non-solar experiments. Eight were launched successfully into ...

(OSO). The observations showed that zodiacal light is highly polarized, and that its intensity and polarization are nearly constant in time. The OSO instruments also recorded terrestrial lightning and demonstrated the remarkable fact that there are ten times as many flashes over the land as over the ocean. This difference remains unexplained.

Infrared astronomy

In 1963, Ney went to Australia on sabbatical leave, where he helped Robert Hanbury Brown andRichard Q. Twiss

Richard Quintin Twiss (24 August 1920 – 20 May 2005) was a British astronomer. He is known for his work on the Hanbury Brown and Twiss effect with Robert Hanbury Brown. It led to the development of the Hanbury Brown-Twiss intensity interferomete ...

to construct the Narrabri Stellar Intensity Interferometer. When he returned, Ney left behind a working instrument, but with the advice of Fred Hoyle

Sir Fred Hoyle (24 June 1915 – 20 August 2001) was an English astronomer who formulated the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis and was one of the authors of the influential B2FH paper, B2FH paper. He also held controversial stances on oth ...

, who he met in Australia, had decided to focus his attention on a field of broader scope: infrared astronomy

Infrared astronomy is a sub-discipline of astronomy which specializes in the astronomical observation, observation and analysis of astronomical objects using infrared (IR) radiation. The wavelength of infrared light ranges from 0.75 to 300 microm ...

. His students, Wayne Stein and Fred Gillett, who had participated in the eclipse expeditions, were eager to work in this area. At this time, there were only two infrared astronomers: Frank J. Low, at the University of Arizona

The University of Arizona (Arizona, U of A, UArizona, or UA) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Tucson, Arizona, United States. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, it ...

, and Gerry Neugebauer

Gerhart "Gerry" Neugebauer (3 September 1932 – 26 September 2014) was an American astronomer known for his pioneering work in infrared astronomy.

Neugebauer was born in Göttingen, Germany and was the son of Otto Neugebauer, an Austrian-Amer ...

at the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small group of institutes ...

. To learn more, Ney and his technician, Jim Stoddart, went to Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, where Low, who Ney dubbed "The Pope of infrared astronomy", familiarized them with his newly developed low temperature bolometer

A bolometer is a device for measuring radiant heat by means of a material having a temperature-dependent electrical resistance. It was invented in 1878 by the American astronomer Samuel Pierpont Langley.

Principle of operation

A bolometer ...

s. After Stein completed his Ph.D. in 1964, he went to Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

to help Professor Robert E. Danielson, an earlier Ney student, carry out infrared observations on Stratoscope II. Similarly, Larry Peterson convinced Gillett to begin a program in infrared astronomy at the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego in communications material, formerly and colloquially UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California, United States. Es ...

(UCSD). Soon, Stein joined Gillett at UCSD.

Until Ney began his infrared studies, astronomical research at Minnesota had been carried out mainly by Willem Luyten, who was an expert on white dwarf

A white dwarf is a Compact star, stellar core remnant composed mostly of electron-degenerate matter. A white dwarf is very density, dense: in an Earth sized volume, it packs a mass that is comparable to the Sun. No nuclear fusion takes place i ...

stars and is credited with coining this name in 1922. When Luyten retired in 1967, he was replaced by Nick Woolf, who had been involved with Stratoscope II, and whom Ney had recruited from the University of Texas

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 students as of fall 2 ...

. With this addition, the department's research emphasis shifted decisively to infrared astronomy, and Minnesota became a significant presence in this nascent field.

O'Brien Observatory

Infrared astronomy began in Minnesota under a severe competitive disadvantage: the lack of a nearby observatory. Because infrared radiation is primarily absorbed by atmospheric water vapor, infrared observatories were typically on mountain tops, above which there is minimal water. From his knowledge of atmospheric physics, Ney realized that, during its cold winters, the air above Minnesota was as free of water as that above a high mountain. Armed with this insight, he approached Nancy Boggess, who had just taken responsibility for NASA's infrared astronomy programs, and who quickly authorized funding for a Minnesota observatory. Ney persuaded Thomond "Tomy" O'Brien to donate a site on the hills above Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota, which is about 22 miles northeast of Minneapolis. Another 180-acre parcel from the extensive holdings of Thomond's grandfather formed the nucleus of William O'Brien State Park, two miles upriver from Marine. The 30-inchCassegrain reflector

The Cassegrain reflector is a combination of a primary concave mirror and a secondary convex mirror, often used in optical telescopes and Antenna (radio), radio antennas, the main characteristic being that the optical path folds back onto itself, ...

, with which Ney fitted out O'Brien Observatory, saw first light in August 1967. That winter, it was put to use by Ney and Stein. The next winter, Woolf and Ney discovered that infrared radiation

Infrared (IR; sometimes called infrared light) is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than that of visible light but shorter than microwaves. The infrared spectral band begins with the waves that are just longer than those ...

from certain cool stars exhibits a spectral feature which indicates that they are surrounded by grains of carbon and silicate minerals

Silicate minerals are rock-forming minerals made up of silicate groups. They are the largest and most important class of minerals and make up approximately 90 percent of Earth's crust.

In mineralogy, the crystalline forms of silica (silicon dio ...

. Within two years, further work by the Minnesota/UCSD group established that these grains, from which planets are formed, are ubiquitous in circumstellar winds and regions of star formation. At O'Brien, Ney and his Australian colleague, David Allen, carried out imaging studies of the lunar surface which revealed temperature anomalies. To explain them, Allen and Ney suggested that large rocks in contact with deep subsurface layers cooled more slowly than the loosely packed regolith

Regolith () is a blanket of unconsolidated, loose, heterogeneous superficial deposits covering solid rock. It includes dust, broken rocks, and other related materials and is present on Earth, the Moon, Mars, some asteroids, and other terrestria ...

.

Mount Lemmon observing facility

Despite the success of the O'Brien Observatory, the Minnesota/UCSD group realized that they needed regular access to a large infrared telescope located at a high altitude site. Consequently, Stein, Gillett, Woolf and Ney proposed to construct a 60-inch infrared telescope. They obtained funding from their two universities, theNational Science Foundation

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an Independent agencies of the United States government#Examples of independent agencies, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that su ...

, and from Fred Hoyle, who offered a contribution with the understanding that aspiring British infrared astronomers would be trained at Minnesota. After Woolf's student, Robert Gehrz, completed a search for suitable sites, the group decided on Mount Lemmon

Mount Lemmon, with a summit elevation of , is the highest point in the Santa Catalina Mountains. It is located in the Coronado National Forest north of Tucson, Arizona, United States. Mount Lemmon was named for botany, botanist Sara Plummer Lemm ...

, whose proximity to a source of liquid helium

Liquid helium is a physical state of helium at very low temperatures at standard atmospheric pressures. Liquid helium may show superfluidity.

At standard pressure, the chemical element helium exists in a liquid form only at the extremely low temp ...

at the University of Arizona

The University of Arizona (Arizona, U of A, UArizona, or UA) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Tucson, Arizona, United States. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, it ...

greatly simplified the logistics. The observatory was named the Mount Lemmon Observing Facility (MLOF). It achieved first light in December 1970.

Teaching

Ney loved to teach. In 1961 he gave the Minnesota department's first honors course in modern physics. He wrote up his lectures as ''Ney's Notes on Relativity'', which were published as the book ''Electromagnetism and Relativity''. In 1964, Ney received Minnesota's outstanding teaching award.Retirement

In 1982, Ney had a serious heart attack. It was followed by open heart surgery on November 28 of that year, which left him withventricular tachycardia

Ventricular tachycardia (V-tach or VT) is a cardiovascular disorder in which fast heart rate occurs in the ventricles of the heart. Although a few seconds of VT may not result in permanent problems, longer periods are dangerous; and multiple ...

for the rest of his life. Taking an active role in the treatment of this condition, Ney applied his knowledge of physics to the study of cardiology and of his heart's electrical system.

This illness slowed Ney down for a few years, but he eventually began to study the effect of radon gas

Radon is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Rn and atomic number 86. It is a radioactive decay, radioactive noble gas and is colorless and odorless. Of the three naturally occurring radon Isotope, isotopes, only radon-222, Rn ha ...

in the atmosphere. He thought that the ionization from radon, which comes from radioactive decay

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

of uranium and thorium in rocks, might account for the high frequency of lightning over land, which had been demonstrated on OSO. This research continued after his retirement in 1990, but did not reach a conclusion before he died on July 9, 1996.

Impact and legacy

Frank Low summarized Ney's career:Ed Ney at Minnesota had a strong belief that being at the scientific forefront meant doing new and difficult things that few others were doing and doing them better. He also felt that to be the best at what you do and the master of your future, you had to be able to learn how to create and advance all of the technology in your own house rather than collaborating too closely with outsiders. Ed's eclectic interests led him in a natural progression from the Manhattan Project, to measurements of cosmic rays, to studies of the physics of balloon flight, to atmospheric and solar physics, to research on the solar corona and the zodiacal light, and finally into the world of astronomy.

Doctoral students

A less visible impact is that made by Ney's students after they finished their PhDs. In 1959, John Naugle joinedGoddard Space Flight Center

The Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) is a major NASA space research laboratory located approximately northeast of Washington, D.C., in Greenbelt, Maryland, United States. Established on May 1, 1959, as NASA's first space flight center, GSFC ...

, and in 1960, took charge of the National Aeronautical and Space Administration's particles and fields research program. Later, he became associate administrator for NASA's Office of Space Science, and from 1977 until 1981, served as NASA Chief Scientist. Similarly, Frank McDonald joined Goddard in 1959 as head of the Energetic Particles Branch in the Space Science Division, where he was project scientist on nine satellite programs. In 1982 he became NASA Chief Scientist, serving until 1987, when he returned to Goddard as associate director/chief scientist.

At Princeton

Princeton University is a private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the Unit ...

Bob Danielson played a key role in the Stratoscope project, where he was a pioneer of infrared astronomy

Infrared astronomy is a sub-discipline of astronomy which specializes in the astronomical observation, observation and analysis of astronomical objects using infrared (IR) radiation. The wavelength of infrared light ranges from 0.75 to 300 microm ...

. James M. Rosen became a professor at the University of Wyoming

The University of Wyoming (UW) is a Public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Laramie, Wyoming, United States. It was founded in March 1886, four years before the territory was admitted as the 44th state, ...

Department of Physics and Astronomy, where he studied atmospheric dust and aerosols. He was also instrumental in the founding of the Wyoming Infrared Observatory

The Wyoming Infrared Observatory (WIRO) is an astronomical observatory owned and operated by the University of Wyoming. It is located on Jelm Mountain, southwest of Laramie, Wyoming, U.S. It was founded in 1975, and observations began at the ...

, which was built by Robert Gherz and John Hackwell, another Ney student.

In 1973, Fred Gillett moved from UCSD to Kitt Peak National Observatory

The Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO) is a United States astronomy, astronomical observatory located on Kitt Peak of the Quinlan Mountains in the Arizona-Sonoran Desert on the Tohono Oʼodham Nation, west-southwest of Tucson, Arizona. With ...

where he helped to develop the Infrared Astronomical Satellite

The Infrared Astronomical Satellite ( Dutch: ''Infrarood Astronomische Satelliet'') (IRAS) was the first space telescope to perform a survey of the entire night sky at infrared wavelengths. Launched on 25 January 1983, its mission lasted ten mo ...

. His investigations on this mission revealed the "Vega

Vega is the brightest star in the northern constellation of Lyra. It has the Bayer designation α Lyrae, which is Latinised to Alpha Lyrae and abbreviated Alpha Lyr or α Lyr. This star is relatively close at only from the Sun, and ...

phenomenon", which refers to dust in orbit around certain young stars. This discovery provided the first solid evidence that planet formation occurs throughout the galaxy. From 1987 to 1989, he was a visiting senior scientist at NASA headquarters

The Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters building at 300 E Street SW in Washington, D.C. houses NASA leadership who provide overall guidance and direction to the US government executive branch agency NASA, under the leadership of the NASA administ ...

, where he played a major role in defining the future of infrared astronomy. More specifically, he made major technical and programmatic contributions to the Space Infrared Telescope, which was renamed the Spitzer Space Telescope

The Spitzer Space Telescope, formerly the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (SIRTF), was an infrared space telescope launched in 2003, that was deactivated when operations ended on 30 January 2020. Spitzer was the third space telescope dedicate ...

after its launch in 2003, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy

The Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) was an 80/20 joint project of NASA and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) to construct and maintain an airborne observatory. NASA awarded the contract for the development of the aircra ...

, which consists of a large infrared telescope aboard an airplane, and 2MASS

The Two Micron All-Sky Survey, or 2MASS, was an astronomical survey of the whole sky in infrared light. It took place between 1997 and 2001, in two different locations: at the U.S. Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory on Mount Hopkins, Arizona, and ...

, which is an infrared all-sky survey. After this administrative interlude, he went to the Gemini Observatory

The Gemini Observatory comprises two 8.1-metre (26.6 ft) telescopes, Gemini North and Gemini South, situated in Hawaii and Chile, respectively. These twin telescopes offer extensive coverage of the northern and southern skies and rank among ...

, where he became project scientist. After Gillett's untimely death on April 22, 2001, the telescope on Mauna Kea

Mauna Kea (, ; abbreviation for ''Mauna a Wākea''); is a dormant Shield volcano, shield volcano on the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii. Its peak is above sea level, making it the List of U.S. states by elevation, highest point in Hawaii a ...

, Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

, was officially named the ''Fredrick C. Gillett Gemini Telescope''.

Honors and awards

*1964 University of Minnesota, Outstanding Teaching Award *1969 NASA Apollo Achievement Award *1971National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

*1974 University of Minnesota, Regent's Professorship

*1975 NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal

The NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal (abbrv. ESAM) was established by NASA on September 15, 1961, when the original ESM was divided into three separate awards. Under its guidelines, the ESAM is awarded for unusually significant scien ...

*1979 American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

*1992 University of Minnesota, Outstanding Achievement Award

Advisory committee memberships

*1955 US Air Force, study group on biological aspects of cosmic radiation *1959United States National Research Council

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), also known as the National Academies, is a congressionally chartered organization that serves as the collective scientific national academy of the United States. The name i ...

, subcommittee on nuclear emulsions

*1960 - 1961 NASA, planetary and interplanetary subcommittee

*1975 National Science Foundation

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an Independent agencies of the United States government#Examples of independent agencies, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that su ...

, visiting committee, astronomy section

*1976 - 1978 Science magazine

''Science'' is the peer-reviewed academic journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and one of the world's top academic journals.

It was first published in 1880, is currently circulated weekly and has a subscrib ...

, editorial board

*1976 - 1979 American Astronomical Society

The American Astronomical Society (AAS, sometimes spoken as "double-A-S") is an American society of professional astronomers and other interested individuals, headquartered in Washington, DC. The primary objective of the AAS is to promote the adv ...

, council

*1979 - 1982 NRC, space sciences board

*1982 - 1985 University of Minnesota, university senate

Selected remarks by Ney

I knew I couldn't compete with Al Nier.

Whatever you don't test will come back to haunt you.

It was fun to get to know the astronauts, but a hard way to do science.

I went to Australia to get my merit badge in astronomy.Commenting on the discovery of carbon and silicate grains around aging stars:

In a cosmology dominated by Hydrogen and Helium, it was a relief to find a source of the material that forms the terrestrial planets.On January 19, 1953, replying to an invitation to attend the Bagnères-de-Bigorre cosmic ray conference from Louis Leprince-Ringuet, whom he addressed as "petit Prince", Ney wrote:

I would like very much to attend the conference in the Pyrenees in July. It would be very good if I could locate some little French girl to teach me the language before I come over. I am looking forward to seeing your "charming" scanners.

Remarks about Ney

The principal at Waukon High School said:Nobody who ever graduated from this school has ever done anything in science, and neither will you.

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Ney, Edward P. 1920 births 1996 deaths People from Waukon, Iowa 20th-century American physicists University of Minnesota faculty University of Minnesota alumni University of Virginia alumni Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Scientists from Minneapolis Fellows of the American Physical Society