Edward Longshanks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was

Edward was born at the

Edward was born at the

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Baili ...

and Lord of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Janu ...

and Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part ...

as a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

of the French king

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the firs ...

. Before his accession to the throne, he was commonly referred to as the Lord Edward. The eldest son of Henry III, Edward was involved from an early age in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included a rebellion by the English baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or kn ...

s. In 1259, he briefly sided with a baronial reform movement, supporting the Provisions of Oxford. After reconciliation with his father, however, he remained loyal throughout the subsequent armed conflict, known as the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the fu ...

. After the Battle of Lewes

The Battle of Lewes was one of two main battles of the conflict known as the Second Barons' War. It took place at Lewes in Sussex, on 14 May 1264. It marked the high point of the career of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, and made h ...

, Edward was held hostage

A hostage is a person seized by an abductor in order to compel another party, one which places a high value on the liberty, well-being and safety of the person seized, such as a relative, employer, law enforcement or government to act, or refr ...

by the rebellious barons, but escaped after a few months and defeated the baronial leader Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester ( – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was a nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the ...

at the Battle of Evesham

The Battle of Evesham (4 August 1265) was one of the two main battles of 13th century England's Second Barons' War. It marked the defeat of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and the rebellious barons by the future King Edward I, who led t ...

in 1265. Within two years the rebellion was extinguished and, with England pacified, Edward left to join the Ninth Crusade

Lord Edward's crusade, sometimes called the Ninth Crusade, was a military expedition to the Holy Land under the command of Edward, Duke of Gascony (future King Edward I of England) in 1271–1272. It was an extension of the Eighth Crusade and was ...

to the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

in 1270. He was on his way home in 1272 when he was informed of his father's death. Making a slow return, he reached England in 1274 and was crowned at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Edward spent much of his reign reforming royal administration and common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

. Through an extensive legal inquiry, he investigated the tenure of various feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

liberties, while the law was reformed through a series of statute

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by ...

s regulating criminal

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in C ...

and property law

Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property (land) and personal property. Property refers to legally protected claims to resources, such as land and personal property, including intellectual pro ...

. However, Edward's attention was increasingly drawn toward military affairs. After suppressing a minor rebellion in Wales in 1276–77, Edward responded to a second rebellion in 1282–83 with a full-scale conquest. After a successful campaign, he subjected Wales to English rule, built a series of castles and towns in the countryside and settled them with English people

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known ...

. Next, his efforts were directed towards the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

. Initially invited to arbitrate a succession dispute, Edward claimed feudal suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

over Scotland, with the ensuing war continuing after Edward's death. Simultaneously, Edward found himself at war with France (a Scottish ally) after King Philip IV confiscated the Duchy of Gascony, which until then had been held in personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

with the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

. Although Edward recovered his duchy, this conflict relieved English military pressure against Scotland. In the mid-1290s, extensive military campaigns required high levels of taxation, and Edward met with both lay

Lay may refer to:

Places

*Lay Range, a subrange of mountains in British Columbia, Canada

*Lay, Loire, a French commune

* Lay (river), France

*Lay, Iran, a village

* Lay, Kansas, United States, an unincorporated community

People

* Lay (surname)

...

and ecclesiastical opposition. When the King died in 1307, he left to his son Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to th ...

an ongoing war with Scotland, along with other financial and political problems that had been left unanswered during his reign.

Edward's temperamental nature and height made him an intimidating man, and he often instilled fear in his contemporaries. Nevertheless, he held the respect of his subjects for the way he embodied the medieval ideal of kingship, as a soldier, an administrator, and a man of faith. Modern historians are divided on their assessment of Edward: while some have praised him for his contribution to the law and administration, others have criticised him for his uncompromising attitude towards his nobility. Edward I is credited with many accomplishments during his reign, including restoring royal authority after the reign of Henry III, establishing Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

as a permanent institution and thereby also a functional system for raising taxes, and reforming the law through statutes. At the same time, he is also often condemned for his wars against Scotland and for expelling the Jews from his kingdom in 1290.

Early years, 1239–1263

Childhood and marriage

Edward was born at the

Edward was born at the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

on the night of 17–18 June 1239, to King Henry III and Eleanor of Provence

Eleanor of Provence (c. 1223 – 24/25 June 1291) was a French noblewoman who became Queen of England as the wife of King Henry III from 1236 until his death in 1272. She served as regent of England during the absence of her spouse in 1253.

A ...

.

''Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

'', an Anglo-Saxon name, was not commonly given among the aristocracy of England after the Norman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

, but Henry was devoted to the veneration of Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

, and decided to name his firstborn son after the saint. Edward's birth was widely celebrated at the royal court and throughout England, and he was baptised

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

three days later at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. Until his accession to the throne in 1272, Edward was commonly referred to as the Lord Edward. Among his childhood friends was his cousin Henry of Almain, son of King Henry's brother Richard of Cornwall

Richard (5 January 1209 – 2 April 1272) was an English prince who was King of the Romans from 1257 until his death in 1272. He was the second son of John, King of England, and Isabella, Countess of Angoulême. Richard was nominal Count of P ...

. Henry of Almain remained a close companion of the prince, both through the civil war that followed, and later during the crusade. Edward was placed in the care of Hugh Giffard – father of the future Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Godfrey Giffard

Godfrey Giffard ( 12351302) was Chancellor of the Exchequer of England, Lord Chancellor of England and Bishop of Worcester.

Early life

Giffard was a son of Hugh Giffard of Boyton in Wiltshire, Nonetheless, he grew up to become an strong, athletic, and imposing man. At he towered over most of his contemporaries, hence his

Edward remained in captivity until March, and even after his release he was kept under strict surveillance. Then, on 28 May, he managed to escape his custodians and joined up with

Edward remained in captivity until March, and even after his release he was kept under strict surveillance. Then, on 28 May, he managed to escape his custodians and joined up with

Edward took the crusader's cross in an elaborate ceremony on 24 June 1268, with his brother

Edward took the crusader's cross in an elaborate ceremony on 24 June 1268, with his brother  By then, the situation in the

By then, the situation in the

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd enjoyed an advantageous situation in the aftermath of the Barons' War. Through the 1267

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd enjoyed an advantageous situation in the aftermath of the Barons' War. Through the 1267

By the 1284

By the 1284

Edward never again went on crusade after his return to England in 1274, but he maintained an intention to do so, and took the cross again in 1287. This intention guided much of his foreign policy, until at least 1291. To stage a European-wide crusade, it was essential to prevent conflict between the sovereigns on

Edward never again went on crusade after his return to England in 1274, but he maintained an intention to do so, and took the cross again in 1287. This intention guided much of his foreign policy, until at least 1291. To stage a European-wide crusade, it was essential to prevent conflict between the sovereigns on

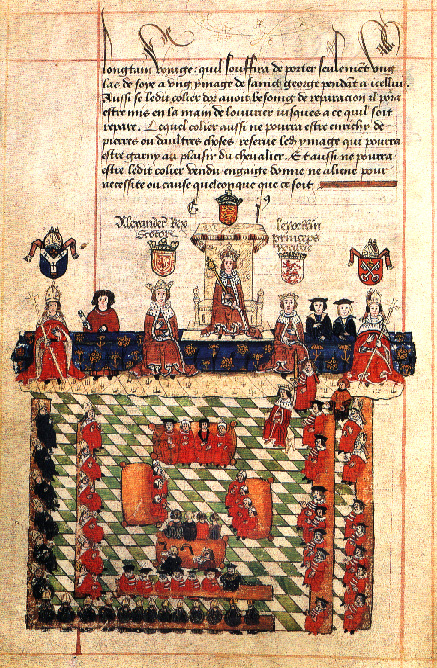

The relationship between England and Scotland by the 1280s was one of relatively harmonious coexistence. The issue of homage did not reach the same level of controversy as it did in Wales; in 1278 King Alexander III of Scotland paid homage to Edward I, who was his brother-in-law, but apparently only for the lands he held of Edward in England. Problems arose only with the Scottish succession crisis of the early 1290s. When Alexander died in 1286, he left as heir to the Scottish throne

The relationship between England and Scotland by the 1280s was one of relatively harmonious coexistence. The issue of homage did not reach the same level of controversy as it did in Wales; in 1278 King Alexander III of Scotland paid homage to Edward I, who was his brother-in-law, but apparently only for the lands he held of Edward in England. Problems arose only with the Scottish succession crisis of the early 1290s. When Alexander died in 1286, he left as heir to the Scottish throne

Edward had a reputation for a fierce and sometimes unpredictable temper, and he could be intimidating; one story tells of how the

Edward had a reputation for a fierce and sometimes unpredictable temper, and he could be intimidating; one story tells of how the

Soon after assuming the throne, Edward set about restoring order and re-establishing royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father. To accomplish this, he immediately ordered an extensive change of administrative personnel. The most important of these was the appointment of Robert Burnell as

Soon after assuming the throne, Edward set about restoring order and re-establishing royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father. To accomplish this, he immediately ordered an extensive change of administrative personnel. The most important of these was the appointment of Robert Burnell as

Edward's reign saw an overhaul of the coinage system, which was in a poor state by 1279. Compared to the coinage already circulating at the time of Edward's accession, the new coins issued proved to be of superior quality. In addition to minting

Edward's reign saw an overhaul of the coinage system, which was in a poor state by 1279. Compared to the coinage already circulating at the time of Edward's accession, the new coins issued proved to be of superior quality. In addition to minting  However, Edward I's frequent military campaigns put a great financial strain on the nation. There were several ways through which the King could raise money for war, including customs

However, Edward I's frequent military campaigns put a great financial strain on the nation. There were several ways through which the King could raise money for war, including customs

In February 1307, Bruce resumed his efforts and started gathering men, and in May he defeated Valence at the

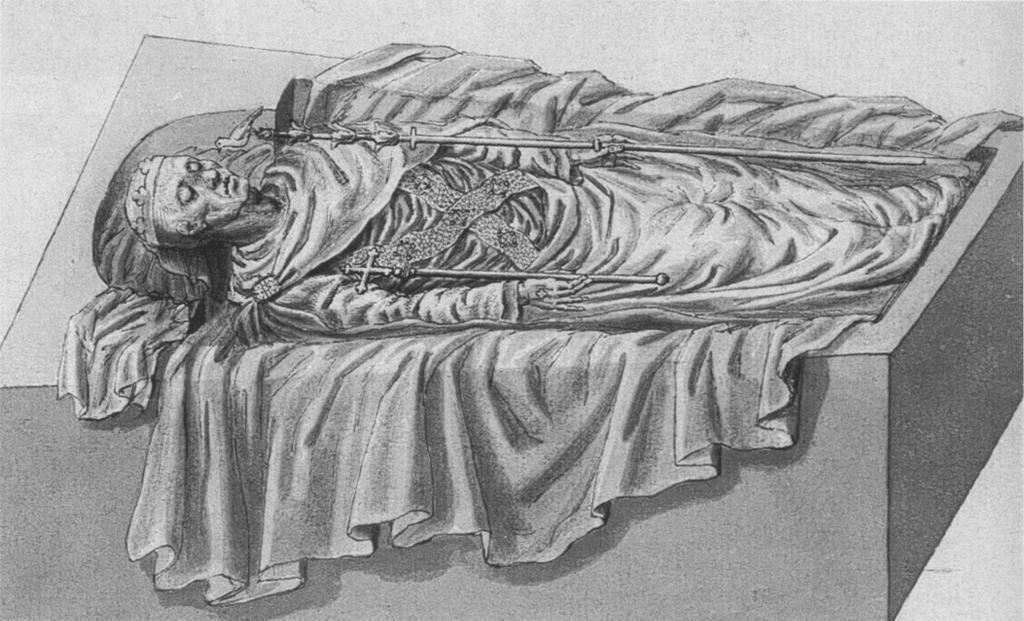

In February 1307, Bruce resumed his efforts and started gathering men, and in May he defeated Valence at the  Edward I's body was brought south, lying in state at Waltham Abbey, before being buried in Westminster Abbey on 27 October. There are few records of the funeral, which cost £473. Edward's tomb was an unusually plain

Edward I's body was brought south, lying in state at Waltham Abbey, before being buried in Westminster Abbey on 27 October. There are few records of the funeral, which cost £473. Edward's tomb was an unusually plain

The first histories of Edward in the 16th and 17th centuries drew primarily on the works of the chroniclers, and made little use of the official records of the period. They limited themselves to general comments on Edward's significance as a monarch, and echoed the chroniclers' praise for his accomplishments. During the 17th century, the lawyer Edward Coke wrote extensively about Edward's legislation, terming the king the "English Justinian" after the renowned Byzantine lawmaker Justinian I. Later in the century, historians used the available record evidence to address the role of parliament and kingship under Edward, drawing comparisons between his reign and the political strife of their own century. Eighteenth-century historians established a picture of Edward as an able, if ruthless, monarch, conditioned by the circumstances of his own time.

The influential Victorian historian William Stubbs instead suggested that Edward had actively shaped national history, forming English laws and institutions, and helping England to develop a parliamentary and constitutional monarchy. His strengths and weaknesses as a ruler were considered to be emblematic of the English people as a whole. Stubbs' student, Thomas Tout, initially adopted the same perspective, but after extensive research into Edward's royal household, and backed by the research of his contemporaries into the early parliaments of the period, he changed his mind. Tout came to view Edward as a self-interested, conservative leader, using the parliamentary system as "the shrewd device of an autocrat, anxious to use the mass of the people as a check upon his hereditary foes among the greater baronage."

Historians in the 20th and 21st century have conducted extensive research on Edward and his reign. Most have concluded this was a highly significant period in English medieval history, some going further and describing Edward as one of the great medieval kings, although most also agree that his final years were less successful than his early decades in power. Three major academic narratives of Edward have been produced during this period. F. M. Powicke's volumes, published in 1947 and 1953, forming the standard works on Edward for several decades, were largely positive in praising the achievements of his reign, and in particular his focus on justice and the law. In 1988,

The first histories of Edward in the 16th and 17th centuries drew primarily on the works of the chroniclers, and made little use of the official records of the period. They limited themselves to general comments on Edward's significance as a monarch, and echoed the chroniclers' praise for his accomplishments. During the 17th century, the lawyer Edward Coke wrote extensively about Edward's legislation, terming the king the "English Justinian" after the renowned Byzantine lawmaker Justinian I. Later in the century, historians used the available record evidence to address the role of parliament and kingship under Edward, drawing comparisons between his reign and the political strife of their own century. Eighteenth-century historians established a picture of Edward as an able, if ruthless, monarch, conditioned by the circumstances of his own time.

The influential Victorian historian William Stubbs instead suggested that Edward had actively shaped national history, forming English laws and institutions, and helping England to develop a parliamentary and constitutional monarchy. His strengths and weaknesses as a ruler were considered to be emblematic of the English people as a whole. Stubbs' student, Thomas Tout, initially adopted the same perspective, but after extensive research into Edward's royal household, and backed by the research of his contemporaries into the early parliaments of the period, he changed his mind. Tout came to view Edward as a self-interested, conservative leader, using the parliamentary system as "the shrewd device of an autocrat, anxious to use the mass of the people as a check upon his hereditary foes among the greater baronage."

Historians in the 20th and 21st century have conducted extensive research on Edward and his reign. Most have concluded this was a highly significant period in English medieval history, some going further and describing Edward as one of the great medieval kings, although most also agree that his final years were less successful than his early decades in power. Three major academic narratives of Edward have been produced during this period. F. M. Powicke's volumes, published in 1947 and 1953, forming the standard works on Edward for several decades, were largely positive in praising the achievements of his reign, and in particular his focus on justice and the law. In 1988,

By his first wife Eleanor of Castile, Edward had at least fourteen children, perhaps as many as sixteen. Of these, five daughters survived into adulthood, but only one son outlived his father, becoming King Edward II (1307–1327). Edward's children with Eleanor were:

#Katherine (1261 or 1263 – September 1264)

#Joan (1265 – before 7 September 1265)

#John (10 July 1266 – 3 August 1271)

# Henry (6 May 1268 – 14 October 1274)

#Eleanor of England (1269–1298), Eleanor (18 June 1269 – 19 August 1298)

#Unnamed daughter (1271 – 1271 or 1272)

#Joan of Acre, Joan (1272 – 23 April 1307)

#Alphonso, Earl of Chester, Alphonso (24 November 1273 – 19 August 1284)

#Margaret of England (1275–1333), Margaret (c.15 March 1275 – after 11 March 1333)

#Berengaria (May 1276 – between 1277 and 1278)

#Unnamed child (January 1278 – 1278)

#Mary of Woodstock, Mary (11 March 1278 – before 8 July 1332)

#Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, Elizabeth (August 1282 – )

#Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327)

By his first wife Eleanor of Castile, Edward had at least fourteen children, perhaps as many as sixteen. Of these, five daughters survived into adulthood, but only one son outlived his father, becoming King Edward II (1307–1327). Edward's children with Eleanor were:

#Katherine (1261 or 1263 – September 1264)

#Joan (1265 – before 7 September 1265)

#John (10 July 1266 – 3 August 1271)

# Henry (6 May 1268 – 14 October 1274)

#Eleanor of England (1269–1298), Eleanor (18 June 1269 – 19 August 1298)

#Unnamed daughter (1271 – 1271 or 1272)

#Joan of Acre, Joan (1272 – 23 April 1307)

#Alphonso, Earl of Chester, Alphonso (24 November 1273 – 19 August 1284)

#Margaret of England (1275–1333), Margaret (c.15 March 1275 – after 11 March 1333)

#Berengaria (May 1276 – between 1277 and 1278)

#Unnamed child (January 1278 – 1278)

#Mary of Woodstock, Mary (11 March 1278 – before 8 July 1332)

#Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, Elizabeth (August 1282 – )

#Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327)

Edward I

at the Royal Family website * *

Edward I

from the online ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Edward 01 Of England Edward I of England, 1239 births 1307 deaths 13th-century English monarchs 14th-century English monarchs Burials at Westminster Abbey Christians of Lord Edward's crusade English people of French descent High Sheriffs of Bedfordshire High Sheriffs of Buckinghamshire Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports People from Westminster English people of the Wars of Scottish Independence People of the Barons' Wars Deaths from dysentery 13th-century peers of France 14th-century peers of France Earls of Chester Competitors for the Crown of Scotland House of Plantagenet Antisemitism in England Children of Henry III of England Sons of kings Victims of the Order of Assassins

epithet

An epithet (, ), also byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) known for accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, di ...

"Longshanks", meaning "long legs" or "long shins". The historian Michael Prestwich

Michael Charles Prestwich OBE (born 30 January 1943) is an English historian, specialising on the history of medieval England, in particular the reign of Edward I. He is retired, having been Professor of History at Durham University and He ...

states that his "long arms gave him an advantage as a swordsman, long thighs one as a horseman. In youth, his curly hair was blond; in maturity it darkened, and in old age it turned white. The regularity of his features was marred by a drooping left eyelid... His speech, despite a lisp, was said to be persuasive."

In 1254 English fears of a Castilian invasion of the English-held province of Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part ...

induced King Henry to arrange a politically expedient marriage between fifteen-year-old Edward and thirteen-year-old Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was intro ...

, the half-sister of King Alfonso X of Castile

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Ger ...

. They were married on 1 November 1254 in the Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas

The Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas is a monastery of Cistercian nuns located approximately 1.5 km west of the city of Burgos in Spain. The word ''huelgas'', which usually refers to "labour strikes" in modern Spanish, refers i ...

in Castile. As part of the marriage agreement, Alfonso X gave up his claims to Gascony, and Edward received grants of land worth 15,000 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

a year. The endowments King Henry made to Edward in 1254, which included Gascony; most of Ireland, which was granted to Edward with the stipulation that it would never separate from the English crown; and much land in Wales and England, including the earldom of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and a ...

, were sizeable, but they offered Edward little independence. King Henry still retained much control over the land in question, particularly in Ireland, so Edward's power was limited there as well, and the King derived most of the income from those lands. Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester ( – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was a nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led th ...

had been appointed as royal lieutenant of Gascony the year before and, consequently, drew its income, so in practice Edward derived neither authority nor revenue from this province. Around December, Edward and Eleanor entered Gascony, where they were warmly received by the populace. Here, Edward styled himself as 'ruling Gascony as prince and lord', a move that the historian J.S. Hamilton asserts was a show of his blooming political independence.

From 1254 to 1257, Edward was under the influence of his mother's relatives, known as the Savoyards, the most notable of whom was Peter II of Savoy

Peter II (120315 May 1268), called the Little Charlemagne, held the Honour of Richmond, Yorkshire, England (but not the Earldom), from April 1240 until his death, holder of the Honour of l’Aigle, and was Count of Savoy (now part of France, Sw ...

, the Queen's uncle. After 1257, Edward became increasingly close to the Lusignan

The House of Lusignan ( ; ) was a royal house of French origin, which at various times ruled several principalities in Europe and the Levant, including the kingdoms of Jerusalem, Cyprus, and Armenia, from the 12th through the 15th centuries duri ...

faction – the half-brothers of his father Henry III – led by such men as William de Valence. This association was significant because the two groups of privileged foreigners were resented by the established English aristocracy, who would be at the centre of the ensuing years' baronial reform movement. Edward's ties to his Lusignan kinsmen were viewed unfavorably by contemporaries, including the chronicler

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

, who circulated tales of unruly and violent conduct by Edward's inner circle, which raised questions about his personal qualities.

Early ambitions

Edward had shown independence in political matters as early as 1255, when he sided with the Soler family in Gascony, in the ongoing conflict between the Soler and Colomb families. This ran contrary to his father's policy of mediation between the local factions. In May 1258, a group ofmagnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s drew up a document for reform of the King's government – the so-called Provisions of Oxford – largely directed against the Lusignans. Edward stood by his political allies and strongly opposed the Provisions. The reform movement succeeded in limiting the Lusignan influence, however, and gradually Edward's attitude started to change. In March 1259, he entered into a formal alliance with one of the main reformers, Richard de Clare, 6th Earl of Gloucester

Richard de Clare, 5th Earl of Hertford, 6th Earl of Gloucester, 2nd Lord of Glamorgan, 8th Lord of Clare (4 August 1222 – 14 July 1262) was the son of Gilbert de Clare, 4th Earl of Hertford and Isabel Marshal.History of Tewkesbury by James Be ...

. Then, on 15 October 1259, he announced that he supported the barons' goals, and their leader, Simon de Montfort.

The motive behind Edward's change of heart could have been purely pragmatic; Montfort was in a good position to support his cause in Gascony. When the King left for France in November, Edward's behaviour turned into pure insubordination. He made several appointments to advance the cause of the reformers, causing his father to believe that Edward was considering a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

. When the King returned from France, he initially refused to see his son, but through the mediation of the Earl of Cornwall and Boniface, Archbishop of Canterbury

Boniface of Savoy ( – 18 July 1270) was a medieval Bishop of Belley in Savoy and Archbishop of Canterbury in England. He was the son of Thomas, Count of Savoy, and owed his initial ecclesiastical posts to his father. Other members of hi ...

, the two were eventually reconciled. Edward was sent abroad, and in November 1260 he again united with the Lusignans, who had been exiled to France.

Back in England, early in 1262, Edward fell out with some of his former Lusignan allies over financial matters. The next year, King Henry sent him on a campaign in Wales against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

, with only limited results. Around the same time, Montfort, who had been out of the country since 1261, returned to England and reignited the baronial reform movement. It was at this pivotal moment, as the King seemed ready to resign to the barons' demands, that Edward began to take control of the situation. Whereas he had so far been unpredictable and equivocating, from this point on he remained firmly devoted to protecting his father's royal rights. He reunited with some of the men he had alienated the year before – among them his childhood friend, Henry of Almain, and John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey – and retook Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

from the rebels. Through the arbitration of King Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the d ...

, an agreement was made between the two parties. This so-called Mise of Amiens was largely favourable to the royalist side, and laid the seeds for further conflict.

Civil war and crusades, 1264–1273

Second Barons' War

The years 1264–1267 saw the conflict known as theSecond Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the fu ...

, in which baronial forces led by Simon de Montfort fought against those who remained loyal to the King. The first scene of battle was the city of Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east o ...

, which Edward managed to retake from the enemy. When Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby

Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby (1239–1279) was an English nobleman.

He was born at Tutbury Castle in Staffordshire, England, the son of William de Ferrers, 5th Earl of Derby, by his second wife Margaret de Quincy (born 1218), a daugh ...

, came to the assistance of the rebels, Edward negotiated a truce with the Earl, the terms of which Edward later broke. He then captured Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

from Simon de Montfort the Younger before embarking on a retaliatory campaign against Derby's lands. The baronial and royalist forces finally met at the Battle of Lewes

The Battle of Lewes was one of two main battles of the conflict known as the Second Barons' War. It took place at Lewes in Sussex, on 14 May 1264. It marked the high point of the career of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, and made h ...

, on 14 May 1264. Edward, commanding the right wing, performed well, and soon defeated the London contingent of Montfort's forces. Unwisely, however, he followed the scattered enemy in pursuit, and on his return found the rest of the royal army defeated. By the agreement known as the Mise of Lewes

The Mise of Lewes was a settlement made on 14 May 1264 between King Henry III of England and his rebellious barons, led by Simon de Montfort. The settlement was made on the day of the Battle of Lewes, one of the two major battles of the Second B ...

, Edward and his cousin Henry of Almain were given up as hostages to Montfort.

Edward remained in captivity until March, and even after his release he was kept under strict surveillance. Then, on 28 May, he managed to escape his custodians and joined up with

Edward remained in captivity until March, and even after his release he was kept under strict surveillance. Then, on 28 May, he managed to escape his custodians and joined up with Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester

Gilbert de Clare, 6th Earl of Hertford, 7th Earl of Gloucester (2 September 1243 – 7 December 1295) was a powerful English noble. He was also known as "Red" Gilbert de Clare or "The Red Earl", probably because of his hair colour or fiery temp ...

, who had recently defected to the King's side. Montfort's support was now dwindling, and Edward retook Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

and Gloucester with relatively little effort. Meanwhile, Montfort had made an alliance with Llywelyn and started moving east to join forces with his son Simon. Edward managed to make a surprise attack at Kenilworth Castle

Kenilworth Castle is a castle in the town of Kenilworth in Warwickshire, England managed by English Heritage; much of it is still in ruins. The castle was founded during the Norman conquest of England; with development through to the Tudor pe ...

, where the younger Montfort was quartered, before moving on to cut off the earl of Leicester. The two forces then met at the second great encounter of the Barons' War, the Battle of Evesham

The Battle of Evesham (4 August 1265) was one of the two main battles of 13th century England's Second Barons' War. It marked the defeat of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and the rebellious barons by the future King Edward I, who led t ...

, on 4 August 1265. Montfort stood little chance against the superior royal forces, and after his defeat he was killed and mutilated on the field.

Through such episodes as the deception of Derby at Gloucester, Edward acquired a reputation as untrustworthy. During the summer campaign, though, he began to learn from his mistakes, and acted in a way that gained the respect and admiration of his contemporaries. The war did not end with Montfort's death, and Edward participated in the continued campaigning. At Christmas, he came to terms with Simon the Younger and his associates at the Isle of Axholme

The Isle of Axholme is a geographical area in England: a part of North Lincolnshire that adjoins South Yorkshire. It is located between the towns of Scunthorpe and Gainsborough, both of which are in the traditional West Riding of Lindsey, an ...

in Lincolnshire, and in March he led a successful assault on the Cinque Ports

The Confederation of Cinque Ports () is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier ( Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to t ...

. A contingent of rebels held out in the virtually impregnable Kenilworth Castle and did not surrender until the drafting of the conciliatory Dictum of Kenilworth. In April it seemed as if Gloucester would take up the cause of the reform movement, and civil war would resume, but after a renegotiation of the terms of the Dictum of Kenilworth, the parties came to an agreement. Around this time, Edward was made Steward of England and began to exercise influence in the government, but despite this, was little involved in the settlement negotiations following the wars; at this point his main focus was on planning his forthcoming crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

.

Crusade and accession

Edward took the crusader's cross in an elaborate ceremony on 24 June 1268, with his brother

Edward took the crusader's cross in an elaborate ceremony on 24 June 1268, with his brother Edmund Crouchback

Edmund, Earl of Lancaster and Earl of Leicester (16 January 12455 June 1296) nicknamed Edmund Crouchback was a member of the House of Plantagenet. He was the second surviving son of King Henry III of England and Eleanor of Provence. In his chi ...

and cousin Henry of Almain. Among others who committed themselves to the Ninth Crusade were Edward's former adversaries – such as the Earl of Gloucester, though he did not ultimately participate. With the country pacified, the greatest impediment to the project was providing sufficient finances. King Louis IX of France, who was the leader of the crusade, provided a loan of about £17,500. This, however, was not enough; the rest had to be raised through a tax on the laity

In religious organizations, the laity () consists of all members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non- ordained members of religious orders, e.g. a nun or a lay brother.

In both religious and wider secular usage, a lay ...

, which had not been levied since 1237. In May 1270, Parliament granted a tax of a twentieth, in exchange for which the King agreed to reconfirm Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

, and to impose restrictions on Jewish money lending. On 20 August Edward sailed from Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

for France. Historians have not determined the size of the force with any certainty, but Edward probably brought with him around 225 knights and altogether fewer than 1000 men.

Originally, the Crusaders intended to relieve the beleaguered Christian stronghold of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

, but King Louis had been diverted to Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

. Louis and his brother Charles of Anjou

Charles I (early 1226/12277 January 1285), commonly called Charles of Anjou, was a member of the royal Capetian dynasty and the founder of the second House of Anjou. He was Count of Provence (1246–85) and Forcalquier (1246–48, 1256–85) ...

, the king of Sicily

The monarchs of Sicily ruled from the establishment of the County of Sicily in 1071 until the "perfect fusion" in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1816.

The origins of the Sicilian monarchy lie in the Norman conquest of southern Italy which occ ...

, decided to attack the emirate to establish a stronghold in North Africa. The plans failed when the French forces were struck by an epidemic which, on 25 August, took the life of Louis himself. By the time Edward arrived at Tunis, Charles had already signed a treaty with the emir, and there was little else to do but return to Sicily. The crusade was postponed until the following spring, but a devastating storm off the coast of Sicily dissuaded both Charles and Philip III (Louis's successor) from any further campaigning. Edward decided to continue alone, and on 9 May 1271 he finally landed at Acre.

By then, the situation in the

By then, the situation in the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

was a precarious one. Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

was reconquered by the Muslims in 1244, and Acre was now the centre of the Christian state

A Christian state is a country that recognizes a form of Christianity as its official religion and often has a state church (also called an established church), which is a Christian denomination that supports the government and is supported by ...

. The Muslim states were on the offensive under the Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

leadership of Baibars

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari ( ar, الملك الظاهر ركن الدين بيبرس البندقداري, ''al-Malik al-Ẓāhir Rukn al-Dīn Baybars al-Bunduqdārī'') (1223/1228 – 1 July 1277), of Turkic Kipchak ...

, and were now threatening Acre itself. Though Edward's men were an important addition to the garrison, they stood little chance against Baibars' superior forces, and an initial raid at nearby St Georges-de-Lebeyne in June was largely futile. An embassy to the Ilkhan

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm, ...

Abaqa

Abaqa Khan (27 February 1234 – 4 April 1282, mn, Абаха/Абага хан (Khalkha Cyrillic), ( Traditional script), "paternal uncle", also transliterated Abaġa), was the second Mongol ruler (''Ilkhan'') of the Ilkhanate. The son of Hul ...

(1234–1282) of the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

helped bring about an attack on Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

in the north, which helped to distract Baibars' forces. In November, Edward led a raid on Qaqun

Qaqun ( ar, قاقون) was a Palestinian Arab village located northwest of the city of Tulkarm at the only entrance to Mount Nablus from the coastal Sharon plain.

Evidence of organized settlement in Qaqun dates back to the period of Assyrian ...

, which could have served as a bridgehead to Jerusalem, but both the Mongol invasion and the attack on Qaqun failed. Things now seemed increasingly desperate, and in May 1272 Hugh III of Cyprus

Hugh III (french: Hugues; – 24 March 1284), also called Hugh of Antioch-Lusignan and the Great, was the king of Cyprus from 1267 and king of Jerusalem from 1268. Born into the family of the princes of Antioch, he effectively ruled as regen ...

, who was the nominal king of Jerusalem

The King of Jerusalem was the supreme ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Crusader state founded in Jerusalem by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade, when the city was conquered in 1099.

Godfrey of Bouillon, the first ruler of ...

, signed a ten-year truce with Baibars. Edward was initially defiant, but an assassination attempt by a Syrian Nizari

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

(Assassin) supposedly sent by Baibars in June 1272 finally forced him to abandon any further campaigning. Although he managed to kill the assassin, he was struck in the arm by a dagger feared to be poisoned, and became severely weakened over the following months.

It was not until 24 September 1272 that Edward left Acre. Arriving in Sicily, he was met with the news that his father had died on 16 November 1272. Edward was deeply saddened by this news, but rather than hurrying home at once, he made a leisurely journey northwards. This was due partly to his still-poor health, but also to a lack of urgency. The political situation in England was stable after the mid-century upheavals, and Edward was proclaimed king after his father's death, rather than at his own coronation, as had until then been customary. In Edward's absence, the country was governed by a royal council, led by Robert Burnell

Robert Burnell (sometimes spelled Robert Burnel;Harding ''England in the Thirteenth Century'' p. 159 c. 1239 – 25 October 1292) was an English bishop who served as Lord Chancellor of England from 1274 to 1292. A native of Shropshire, h ...

. The new king embarked on an overland journey through Italy and France, during which he visited Pope Gregory X

Pope Gregory X ( la, Gregorius X; – 10 January 1276), born Teobaldo Visconti, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 September 1271 to his death and was a member of the Secular Franciscan Order. He was ...

and paid homage to Philip III in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

for his French domains. Before returning to England, however, Edward travelled by way of Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Sa ...

to receive homage from his uncle Count Philip I for a number of castles in the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

held by a treaty in 1246. At Philip’s castle of Saint-Georges-d'Espéranche

Saint-Georges-d'Espéranche () is a commune in the Isère department in southeastern France.

History

The medieval architect and castle builder for Edward I of England, Master James of Saint George, also known as Jacques de Saint-Georges d'Esp� ...

in June 1273, Edward met Philip's castle-builder James of Saint George

Master James of Saint George (–1309; French: , Old French: Mestre Jaks, Latin: Magister Jacobus de Sancto Georgio) was a master of works/architect from Savoy, described by historian Marc Morris as "one of the greatest architects of the Europ ...

, the man who would later build castles for him in north Wales. Following Paris and Savoy, Edward went to Gascony in order to sort out its affairs and put down a revolt headed by Gaston de Béarn. While there, he launched an investigation into his feudal possessions, which, as Hamilton puts it, reflects "Edward's keen interest in administrative efficiency... ndreinforced Edward's position as lord in Aquitaine and strengthened the bonds of loyalty between the king-duke and his subjects". Around the same time, the King organized political alliances with the kingdoms in Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

. His four year old daughter Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was intro ...

was promised in marriage to Alfonso

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century (Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula. ...

, the heir to the Kingdom of Aragon

The Kingdom of Aragon ( an, Reino d'Aragón, ca, Regne d'Aragó, la, Regnum Aragoniae, es, Reino de Aragón) was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon ...

, whereas Edward's own heir Henry was betrothed to Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*: Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

*Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

, heiress to the Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre (; , , , ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona (), was a Basque kingdom that occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, alongside the Atlantic Ocean between present-day Spain and France.

The medieval state took ...

. However, neither union would come into fruition. Only on 2 August 1274 did Edward return to England, landing at Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

. The thirty-five year old King Edward was crowned on 19 August at Westminster Abbey, alongside Queen Eleanor. Immediately after being anointed and crowned by Robert Kilwardby

Robert Kilwardby ( c. 1215 – 11 September 1279) was an Archbishop of Canterbury in England and a cardinal. Kilwardby was the first member of a mendicant order to attain a high ecclesiastical office in the English Church.

Life

Kilwardby s ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, Edward removed his crown, saying that he did not intend on wearing it until he had recovered all the crown lands lost under his father's reign.

Early reign, 1274–1296

Welsh wars

Conquest

Treaty of Montgomery

The Treaty of Montgomery was an Anglo-Welsh treaty signed on 29 September 1267 in Montgomeryshire by which Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was acknowledged as Prince of Wales by King Henry III of England (r. 1216–1272). It was the only time an English ...

, he officially obtained land he had conquered in the Four Cantrefs of Perfeddwlad and was recognised in his title of Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

. Armed conflicts nevertheless continued, in particular with certain dissatisfied Marcher Lords

A Marcher lord () was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border (known as the Welsh Marches) between England and Wales.

A Marcher lord was the English equivalent of a margrave (in the Holy Roman Empire) or a marquis (in ...

, such as Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, Roger Mortimer and Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford

Humphrey (VI) de Bohun (c. 1249 – 31 December 1298), 3rd Earl of Hereford and 2nd Earl of Essex, was an English nobleman known primarily for his opposition to King Edward I over the ''Confirmatio Cartarum.''Fritze and Robison, (2002). ...

. Problems were exacerbated when Llywelyn's younger brother Dafydd Dafydd is a Welsh masculine given name, related to David, and more rarely a surname. People so named include:

Given name Medieval era

:''Ordered chronologically''

* Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd (c. 1145-1203), Prince of Gwynedd

* Dafydd ap Gruffydd (12 ...

and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn

Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn (died c. 1286) was a Welsh king who was lord of the part of Powys known as Powys Wenwynwyn and sided with Edward I in his conquest of Wales of 1277 to 1283.

Gruffydd was the son of Gwenwynwyn and Margaret Corbet. He was st ...

of Powys

Powys (; ) is a county and preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh successor state, petty kingdom and principality that emerged during the Middle Ages following the end of Roman rule in Britain.

Geog ...

, after failing in an assassination attempt against Llywelyn, defected to the English in 1274. Citing ongoing hostilities and Edward's harbouring of his enemies, Llywelyn refused to do homage to the King. For Edward, a further provocation came from Llywelyn's planned marriage to Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was intro ...

, daughter of Simon de Montfort.

In November 1276, war was declared. Initial operations were launched under the captaincy of Mortimer, Edward's brother Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, and William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick

William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick (c. 1238 – 1298) was the eldest of eight children of William de Beauchamp of Elmley and his wife Isabel de Mauduit. He was an English nobleman and soldier, described as a “vigorous and innovative mili ...

. Support for Llywelyn was weak among his own countrymen. In July 1277 Edward invaded with a force of 15,500, of whom 9,000 were Welshmen. The campaign never came to a major battle, and Llywelyn soon realised he had no choice but to surrender. By the Treaty of Aberconwy

The Treaty of Aberconwy was signed on the 10th of November 1277, the treaty was by King Edward I of England and Llewelyn the Last, Prince of Wales, following Edward’s invasion of Llewelyn’s territories earlier that year. The treaty granted p ...

in November 1277, he was left only with the land of Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, an ...

, though he was allowed to retain the title of Prince of Wales.

When war broke out again in 1282, it was an entirely different undertaking. For the Welsh, this war was over national identity, enjoying wide support, provoked particularly by attempts to impose English law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, b ...

on Welsh subjects. For Edward, it became a war of conquest rather than simply a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beh ...

, like the former campaign. The war started with a rebellion by Dafydd, who was discontented with the reward he had received from Edward in 1277. Llywelyn and other Welsh chieftains soon joined in, and initially the Welsh experienced military success. In June, Gloucester was defeated at the Battle of Llandeilo Fawr. On 6 November, while John Peckham

John Peckham (c. 1230 – 8 December 1292) was Archbishop of Canterbury in the years 1279–1292. He was a native of Sussex who was educated at Lewes Priory and became a Friar Minor about 1250. He studied at the University of Paris under ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, was conducting peace negotiations, Edward's commander of Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

, Luke de Tany, decided to carry out a surprise attack. A pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, uses floats or shallow- draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maximum load that they can carry ...

had been built to the mainland, but shortly after Tany and his men crossed over, they were ambushed by the Welsh and suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Moel-y-don

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

. The Welsh advances ended on 11 December, however, when Llywelyn was lured into a trap and killed at the Battle of Orewin Bridge

The Battle of Orewin Bridge (also known as the Battle of Irfon Bridge) was fought between English (led by the Marcher Lords) and Welsh armies on 11 December 1282 near Builth Wells in mid-Wales. It was a decisive defeat for the Welsh because ...

. The conquest of Gwynedd was complete with the capture in June 1283 of Dafydd, who was taken to Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

and executed as a traitor the following autumn; King Edward ordered Dafydd's head to be publicly exhibited on London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It re ...

. Further rebellions occurred in 1287–88 and, more seriously, in 1294, under the leadership of Madog ap Llywelyn

Madog ap Llywelyn (died after 1312) was the leader of the Welsh revolt of 1294–95 against English rule in Wales and proclaimed "Prince of Wales". The revolt was surpassed in longevity only by the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr in the 15th century. Ma ...

, a distant relative of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. This last conflict demanded the King's own attention, but in both cases the rebellions were put down.

Colonisation

By the 1284

By the 1284 Statute of Rhuddlan

The Statute of Rhuddlan (12 Edw 1 cc.1–14; cy, Statud Rhuddlan ), also known as the Statutes of Wales ( la, Statuta Valliae) or as the Statute of Wales ( la, Statutum Valliae, links=no), provided the constitutional basis for the government of ...

, the Principality of Wales

The Principality of Wales ( cy, Tywysogaeth Cymru) was originally the territory of the native Welsh princes of the House of Aberffraw from 1216 to 1283, encompassing two-thirds of modern Wales during its height of 1267–1277. Following the co ...

was incorporated into England and was given an administrative system like the English, with counties policed by sheriffs. English law was introduced in criminal cases, though the Welsh were allowed to maintain their own customary laws in some cases of property disputes. After 1277, and increasingly after 1283, Edward embarked on a full-scale project of English settlement of Wales, creating new towns like Flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

, Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth () is a university and seaside town as well as a community in Ceredigion, Wales. Located in the historic county of Cardiganshire, means "the mouth of the Ystwyth". Aberystwyth University has been a major educational location i ...

and Rhuddlan

Rhuddlan () is a town, community, and electoral ward in the county of Denbighshire, Wales, in the historic county of Flintshire. Its associated urban zone is mainly on the right bank of the Clwyd; it is directly south of seafront town Rhyl. ...

. Their new residents were English migrants, with the local Welsh banned from living inside them, and many were protected by extensive walls.

An extensive project of castle-building was also initiated, under the direction of James of Saint George, a prestigious architect whom Edward had met in Savoy on his return from the crusade. These included the Beaumaris

Beaumaris ( ; cy, Biwmares ) is a town and community on the Isle of Anglesey in Wales, of which it is the former county town of Anglesey. It is located at the eastern entrance to the Menai Strait, the tidal waterway separating Anglesey from th ...

, Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a royal town, community and port in Gwynedd, Wales, with a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the eastern shore of the Menai Strait, opposite the Isle of Anglesey. The city of Bangor ...

, Conwy

Conwy (, ), previously known in English as Conway, is a walled market town, community and the administrative centre of Conwy County Borough in North Wales. The walled town and castle stand on the west bank of the River Conwy, facing Deganwy on ...

and Harlech

Harlech () is a seaside resort and community in Gwynedd, north Wales and formerly in the historic county of Merionethshire. It lies on Tremadog Bay in the Snowdonia National Park. Before 1966, it belonged to the Meirionydd District of the 19 ...

castles, intended to act both as fortresses and royal palaces for the King. His programme of castle building in Wales heralded the introduction of the widespread use of arrowslit

An arrowslit (often also referred to as an arrow loop, loophole or loop hole, and sometimes a balistraria) is a narrow vertical aperture in a fortification through which an archer can launch arrows or a crossbowman can launch bolts.

The interio ...

s in castle walls across Europe, drawing on Eastern influences. Also a product of the Crusades was the introduction of the concentric castle

A concentric castle is a castle with two or more concentric curtain walls, such that the outer wall is lower than the inner and can be defended from it. The layout was square (at Belvoir and Beaumaris) where the terrain permitted, or an irreg ...

, and four of the eight castles Edward founded in Wales followed this design. The castles made a clear, imperial statement about Edward's intentions to rule North Wales permanently, and drew on imagery associated with the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

in an attempt to build legitimacy for his new regime.

In 1284, King Edward had his son Edward (later Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to th ...

) born at Caernarfon Castle, probably to make a deliberate statement about the new political order in Wales. David Powel, a 16th-century clergyman, suggested that the baby was offered to the Welsh as a prince "that was borne in Wales and could speake never a word of English", but there is no evidence to support this widely-reported account. In 1301 at Lincoln, the young Edward became the first English prince to be invested with the title of Prince of Wales, when the King granted him the Earldom of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and a ...

and lands across North Wales.; The King seems to have hoped that this would help in the pacification of the region, and that it would give his son more financial independence.

Diplomacy and war on the continent

Edward never again went on crusade after his return to England in 1274, but he maintained an intention to do so, and took the cross again in 1287. This intention guided much of his foreign policy, until at least 1291. To stage a European-wide crusade, it was essential to prevent conflict between the sovereigns on

Edward never again went on crusade after his return to England in 1274, but he maintained an intention to do so, and took the cross again in 1287. This intention guided much of his foreign policy, until at least 1291. To stage a European-wide crusade, it was essential to prevent conflict between the sovereigns on the continent

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

. A major obstacle to this was represented by the conflict between the French Capetian House of Anjou

The Capetian House of Anjou or House of Anjou-Sicily, was a royal house and cadet branch of the direct French House of Capet, part of the Capetian dynasty. It is one of three separate royal houses referred to as ''Angevin'', meaning "from Anjou" ...

ruling southern Italy and the Kingdom of Aragon in Spain. In 1282, the citizens of Palermo rose up against Charles of Anjou and turned for help to Peter III of Aragon

Peter III of Aragon ( November 1285) was King of Aragon, King of Valencia (as ), and Count of Barcelona (as ) from 1276 to his death. At the invitation of some rebels, he conquered the Kingdom of Sicily and became King of Sicily in 1282, pre ...

, in what has become known as the Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian Vespers ( it, Vespri siciliani; scn, Vespiri siciliani) was a successful rebellion on the island of Sicily that broke out at Easter 1282 against the rule of the French-born king Charles I of Anjou, who had ruled the Kingdom of ...

. In the war that followed, Charles of Anjou's son, Charles of Salerno

Charles II, also known as Charles the Lame (french: Charles le Boiteux; it, Carlo lo Zoppo; 1254 – 5 May 1309), was King of Naples, Count of Provence and Forcalquier (1285–1309), Prince of Achaea (1285–1289), and Count of Anjou and Maine ...

, was taken prisoner by the Aragonese. The French began planning an attack on Aragon, raising the prospect of a large-scale European war. To Edward, it was imperative that such a war be avoided, and in Paris in 1286 he brokered a truce between France and Aragon that helped secure Charles' release. As far as the crusades were concerned, however, Edward's efforts proved ineffective. A devastating blow to his plans came in 1291, when the Mamluks captured Acre, the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land.

Edward had long been deeply involved in the affairs of his own Duchy of Gascony

The Duchy of Gascony or Duchy of Vasconia ( eu, Baskoniako dukerria; oc, ducat de Gasconha; french: duché de Gascogne, duché de Vasconie) was a duchy located in present-day southwestern France and northeastern Spain, an area encompassing the m ...

. In 1278 he assigned an investigating commission to his trusted associates Otto de Grandson and the chancellor Robert Burnell

Robert Burnell (sometimes spelled Robert Burnel;Harding ''England in the Thirteenth Century'' p. 159 c. 1239 – 25 October 1292) was an English bishop who served as Lord Chancellor of England from 1274 to 1292. A native of Shropshire, h ...

, which caused the replacement of the seneschal Luke de Tany. In 1286, Edward visited the region himself and stayed for almost three years. The perennial problem, however, was the status of Gascony within the Kingdom of France, and Edward's role as the French king's vassal. On his diplomatic mission in 1286, Edward had paid homage to the new king, Philip IV, but in 1294 Philip declared Gascony forfeit when Edward refused to appear before him in Paris to discuss the recent conflict between English, Gascon, and French sailors that had resulted in several French ships being captured, along with the sacking of the French port of La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. Wi ...

.

Correspondence between Edward and the Mongol court of the east continued during this time. Diplomatic channels between the two had begun during Edward's time on crusade, regarding a possible alliance to retake the Holy Land for Europe. Edward received Mongol envoys at his court in Gascony while there in 1287, and one of their leaders, Rabban Bar Sauma

Rabban Bar Ṣawma (Syriac language: , ; 1220January 1294), also known as Rabban Ṣawma or Rabban ÇaumaMantran, p. 298 (), was a Turkic Chinese ( Uyghur or possibly Ongud) monk turned diplomat of the "Nestorian" Church of the East in China. ...