Edward Boscawen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the siege, Boscawen was ordered with Sir Charles Knowles to destroy the forts. The task took three weeks and 122 barrels of

During the siege, Boscawen was ordered with Sir Charles Knowles to destroy the forts. The task took three weeks and 122 barrels of

In 1741 Boscawen was part of the fleet sent to attack another Caribbean port,

In 1741 Boscawen was part of the fleet sent to attack another Caribbean port,

On 4 February 1755 Boscawen was promoted vice admiral and given command of a squadron on the

On 4 February 1755 Boscawen was promoted vice admiral and given command of a squadron on the  Boscawen returned to the

Boscawen returned to the

In October 1757 Boscawen was second in command under Admiral

In October 1757 Boscawen was second in command under Admiral

In April 1759 Boscawen took command of a fleet bound for the Mediterranean. His aim was to prevent another planned invasion of Britain by the French. With his flag aboard the newly constructed of 90 guns he blockaded

In April 1759 Boscawen took command of a fleet bound for the Mediterranean. His aim was to prevent another planned invasion of Britain by the French. With his flag aboard the newly constructed of 90 guns he blockaded

The town of Boscawen, New Hampshire is named after him. Two ships and a

The town of Boscawen, New Hampshire is named after him. Two ships and a

History of War – Siege of Louisburg 1758National Trust – Hatchlands ParkOxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Edward BoscawenTregothnan Estate, Cornwall

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Boscawen, Edward 1711 births 1761 deaths Younger sons of viscounts Royal Navy admirals Lords of the Admiralty British military personnel of the French and Indian War Royal Navy personnel of the War of the Austrian Succession Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Truro British MPs 1741–1747 British MPs 1747–1754 British MPs 1754–1761 Burials in Cornwall

Admiral of the Blue

The Admiral of the Blue was a senior rank of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major mar ...

Edward Boscawen, PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a British admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

and Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for the borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle Ag ...

of Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its population was 18,766 in the 2011 census. People of Truro ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. He is known principally for his various naval commands during the 18th century and the engagements that he won, including the siege of Louisburg in 1758 and Battle of Lagos in 1759. He is also remembered as the officer who signed the warrant authorising the execution of Admiral John Byng

Admiral John Byng (baptised 29 October 1704 – 14 March 1757) was a British Royal Navy officer who was court-martialled and executed by firing squad. After joining the navy at the age of thirteen, he participated at the Battle of Cape Pass ...

in 1757, for failing to engage the enemy at the Battle of Minorca (1756). In his political role, he served as a Member of Parliament for Truro from 1742 until his death although due to almost constant naval employment he seems not to have been particularly active. He also served as one of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

on the Board of Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

from 1751 and as a member of the Privy Council from 1758 until his death in 1761.

Early life

The Honourable

''The Honourable'' (British English) or ''The Honorable'' ( American English; see spelling differences) (abbreviation: ''Hon.'', ''Hon'ble'', or variations) is an honorific style that is used as a prefix before the names or titles of certa ...

Edward Boscawen was born in Tregothnan

Tregothnan is a country house and estate near the village of St Michael Penkivel, southeast of Truro, Cornwall, England, which has for many centuries been a possession of the Boscawens.

Geography Location

Tregothnan is located on a hill overl ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

, England, on 19 August 1711, the third son of Hugh Boscawen, 1st Viscount Falmouth

Hugh Boscawen, 1st Viscount Falmouth (pronounced "Boscowen") ( ; ca. 1680 – 25 October 1734), was an English Whig politician who sat in the House of Commons for Cornish constituencies from 1702 until 1720 when he was raised to the peerage ...

(1680–1734) by his wife Charlotte Godfrey (died 1754) elder daughter and co-heiress of Colonel Charles Godfrey, master of the jewel office by his wife Arabella Churchill, the King's mistress, and sister of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

General John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, 1st Prince of Mindelheim, 1st Count of Nellenburg, Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, (26 May 1650 – 16 June 1722 O.S.) was an English soldier and statesman whose career spanned the reign ...

.

The young Edward joined the navy at the age of 12 aboard of 60 guns. ''Superb'' was sent to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

with Admiral Francis Hosier. Boscawen stayed with ''Superb'' for three years during the Anglo-Spanish War. He was subsequently reassigned to , , and under Admiral Sir Charles Wager

Admiral Sir Charles Wager (24 February 1666 – 24 May 1743) was a Royal Navy officer and politician who served as First Lord of the Admiralty from 1733 to 1742. Despite heroic active service and steadfast administration and diplomatic service, ...

and was aboard ''Namur'' when she sailed into Cadiz and Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 158,493 residents in December 2017. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn (pronou ...

following the Treaty of Seville

The Treaty of Seville was signed on 9 November, 1729 between Britain, France, and Spain, formally ending the 1727–1729 Anglo-Spanish War; the Dutch Republic joined the Treaty on 29 November.

However, the Treaty failed to resolve underlying t ...

that ended hostilities between Britain and Spain. On 25 May 1732 Boscawen was promoted lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

and in the August of the same year rejoined his old ship the 44-gun fourth-rate ''Hector'' in the Mediterranean. He remained with her until 16 October 1735 when he was promoted to the 70-gun . On 12 March 1736 Boscawen was promoted by Admiral Sir John Norris to the temporary command of the 50-gun . His promotion was confirmed by the Board of Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

. In June 1738 Boscawen was given command of , a small sixth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a sixth-rate was the designation for small warships mounting between 20 and 28 carriage-mounted guns on a single deck, sometimes with smaller guns on the upper works a ...

of 20 guns. He was ordered to accompany Admiral Edward Vernon

Admiral Edward Vernon (12 November 1684 – 30 October 1757) was an English naval officer. He had a long and distinguished career, rising to the rank of admiral after 46 years service. As a vice admiral during the War of Jenkins' Ear, in 173 ...

to the West Indies in preparation for the oncoming war with Spain.

War of Jenkins' Ear

Porto Bello

The War of Jenkins' Ear proved to be Boscawen's first opportunity for action and when ''Shoreham'' was declared unfit for service he volunteered to accompany Vernon and the fleet sent to attack Porto Bello. During the siege, Boscawen was ordered with Sir Charles Knowles to destroy the forts. The task took three weeks and 122 barrels of

During the siege, Boscawen was ordered with Sir Charles Knowles to destroy the forts. The task took three weeks and 122 barrels of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

to accomplish but the British levelled the forts surrounding the town. Vernon's achievement was hailed in Britain as an outstanding feat of arms and in the furore that surrounded the announcement the patriotic song "Rule, Britannia

"Rule, Britannia!" is a British Patriotism, patriotic song, originating from the 1740 poem "Rule, Britannia" by James Thomson (poet, born 1700), James Thomson and set to music by Thomas Arne in the same year. It is most strongly associated w ...

" was played for the first time. Streets were named after Porto Bello throughout Britain and its colonies. When the fleet returned to Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

''Shoreham'' had been refitted and Boscawen resumed command of her.

Cartagena

In 1741 Boscawen was part of the fleet sent to attack another Caribbean port,

In 1741 Boscawen was part of the fleet sent to attack another Caribbean port, Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( , also ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, bordering the Caribbean sea. Cartagena's past role as a link ...

. Large reinforcements had been sent from Britain, including 8,000 soldiers who were landed to attack the chain of fortresses surrounding the Spanish colonial city. The Spanish had roughly 6,000 troops made up of regular soldiers, sailors and local loyalist natives. The siege lasted for over two months during which period the British troops suffered over 18,000 casualties, the vast majority from disease. Vernon's fleet suffered from dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease, disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, ch ...

, yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

and other illnesses that were widespread throughout the Caribbean during the period. As a result of the battle Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Lea ...

's government collapsed and George II removed his promise of support to the Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

ns if the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

ns advanced into Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

. The defeat of Vernon was a contributing factor to the increased hostilities of the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George ...

. Boscawen had however distinguished himself once more. The land forces that he commanded had been instrumental in capturing Fort San Luis and Boca Chica Castle, and together with Knowles he destroyed the captured forts when the siege was abandoned. For his services he was promoted in May 1742 to the rank of captain and appointed to command the 70-gun ''Prince Frederick'' to replace Lord Aubrey Beauclerk

Lord Aubrey Beauclerk (c. 1710 – 22 March 1741) was an officer of the Royal Navy. He saw service during the War of the Austrian Succession and was killed at the Battle of Cartagena de Indias.

Early naval service

Lord Aubrey was born circa ...

who had died during the siege.

War of the Austrian Succession

In 1742 Boscawen returned in ''Prince Frederick'' to England, where she was paid off and Boscawen joined the fleet commanded by Admiral Norris in the newly built 60-gun . In the same year he was returned as aMember of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Truro, a position he held until his death. At the 1747 general election he was also returned for Saltash

Saltash (Cornish: Essa) is a town and civil parish in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It had a population of 16,184 in 2011 census. Saltash faces the city of Plymouth over the River Tamar and is popularly known as "the Gateway to Corn ...

, but chose to continue to sit for Truro.

In 1744 the French attempted an invasion of England and Boscawen was with the fleet under Admiral Norris when the French fleet were sighted. The French under Admiral Rocquefeuil

Jacques Aymar de Roquefeuil du Bousquet (14 November 1665, in château du Bousquet, Montpeyroux, Rouergue – 8/9 March 1744) was a French Navy admiral.

Family

He was a member of the de Roquefeuil-Blanquefort family from Languedoc in Fran ...

retreated and the British attempts to engage were confounded by a violent storm that swept the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

.

Whilst cruising the Channel, Boscawen had the good fortune to capture the French frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

. She was the first capture of an enemy ship made during the War of Austrian Succession and was commanded by . ''Médée'' was sold and became a successful privateer under her new name ''Boscawen'' commanded by George Walker.

At the end of 1744 Boscawen was given command of , guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usua ...

at the Nore

The Nore is a long bank of sand and silt running along the south-centre of the final narrowing of the Thames Estuary, England. Its south-west is the very narrow Nore Sand. Just short of the Nore's easternmost point where it fades into the cha ...

anchorage

Anchorage () is the largest city in the U.S. state of Alaska by population. With a population of 291,247 in 2020, it contains nearly 40% of the state's population. The Anchorage metropolitan area, which includes Anchorage and the neighboring ...

. He commanded her until 1745 when he was appointed to another of his old ships, HMS ''Namur'', that had been reduced ( razéed) from 90 guns to 74 guns. He was appointed to command a small squadron under Vice-Admiral Martin Martin may refer to:

Places

* Martin City (disambiguation)

* Martin County (disambiguation)

* Martin Township (disambiguation)

Antarctica

* Martin Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land

* Port Martin, Adelie Land

* Point Martin, South Orkney Islands

Austr ...

in the Channel.

First Battle of Cape Finisterre

In 1747 Boscawen was ordered to join Admiral Anson and took an active part in the first Battle of Cape Finisterre. The British fleet sighted the French fleet on 3 May. The French fleet under Admiral de la Jonquière was convoying its merchant fleet to France and the British attacked. The French fleet was almost completely annihilated with all but two of the escorts taken and six merchantmen. Boscawen was injured in the shoulder during the battle by amusket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

ball. Once more the French captain, M. de Hocquart became Boscawen's prisoner and was taken to England.

Command in India

Boscawen was promoted rear-admiral of the blue on 15 July 1747 and was appointed to command a joint operation being sent to theEast Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

. With his flag in ''Namur'', and with five other line of battle ships, a few smaller men of war

''Men of War'' is a real-time tactics video game franchise, based mainly in World War II.

Main series

Soldiers: Heroes of World War II

''Soldiers: Heroes of World War II'' is the original game of the 'Men of War' series, and uses an early GE ...

, and a number of transports Boscawen sailed from England on 4 November 1747. On the outward voyage Boscawen made an abortive attempt to capture Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

by surprise but was driven off by French forces. Boscawen continued on arriving at Fort St. David

Fort St David, now in ruins, was a British fort near the town of Cuddalore, a hundred miles south of Chennai on the Coromandel Coast of India. It is located near silver beach without any maintenance. It was named for the patron saint of Wales b ...

near the town of Cuddalore

Cuddalore, also spelt as Kadalur (), is the city and headquarters of the Cuddalore District in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Situated south of Chennai, Cuddalore was an important port during the British Raj.

While the early history of Cudd ...

on 29 July 1748 and took over command from Admiral Griffin. Boscawen had been ordered to capture and destroy the main French settlement in India at Pondichéry. Factors such as Boscawen's lack of knowledge and experience of land offensives, the failings of the engineers

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the li ...

and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

officers under his command, a lack of secrecy surrounding the operation and the skill of the French governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Joseph François Dupleix

Joseph Marquis Dupleix (23 January 1697 – 10 November 1763) was Governor-General of French India and rival of Robert Clive.

Biography

Dupleix was born in Landrecies, on January 23, 1697. His father, François Dupleix, a wealthy ''fermier gé ...

combined to thwart the attack. The British forces amounting to some 5,000 men captured and destroyed the outlying fort of Aranciopang. This capture was the only success of the operation and after failing to breach the walls of the city the British forces withdrew. Amongst the combatants were a young ensign Robert Clive

Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive, (29 September 1725 – 22 November 1774), also known as Clive of India, was the first British Governor of the Bengal Presidency. Clive has been widely credited for laying the foundation of the British ...

, later known as Clive of India and Major Stringer Lawrence, later Commander-in-Chief, India

During the period of the Company rule in India and the British Raj, the Commander-in-Chief, India (often "Commander-in-Chief ''in'' or ''of'' India") was the supreme commander of the British Indian Army. The Commander-in-Chief and most of his ...

. Lawrence was captured by the French during the retreat and exchanged after the news of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had reached India. Over the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

season Boscawen remained at Fort St David. Fortunately, for the Admiral and his staff, when a storm hit the British outpost Boscawen was ashore but his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

''Namur'' went down with over 600 men aboard.

Boscawen returned to England in 1750. In 1751 Anson became First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

and asked Boscawen to serve on the Admiralty Board. Boscawen remained one of the Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty until his death.

Seven Years' War

On 4 February 1755 Boscawen was promoted vice admiral and given command of a squadron on the

On 4 February 1755 Boscawen was promoted vice admiral and given command of a squadron on the North American Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the ...

. A squadron of partially disarmed French ships of the line were dispatched to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

loaded with reinforcements and Boscawen was ordered to intercept them. The French ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or s ...

to London, the Duc de Mirepoix had informed the government of George II that any act of hostility taken by British ships would be considered an act of war. Thick fog both obstructed Boscawen's reconnaissance and scattered the French ships, but on 8 June Boscawen's squadron sighted the ''Alcide'', ''Lys'' and ''Dauphin Royal'' off Cape Ray off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

. In the ensuing engagement the British captured the ''Alcide'' and ''Lys'' but the ''Dauphin Royal'' escaped into the fog. Amongst the 1,500 men made prisoner was the captain of the ''Alcide''. For M. de Hocquart it was the third time that Boscawen had fought him and taken his ship. Pay amounting to £80,000 was captured aboard the ''Lys''. Boscawen, as vice-admiral commanding the squadron, would have been entitled to a sizeable share in the prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to ...

. The British squadron headed for Halifax to regroup but a fever spread through the ships and the Vice-admiral was forced to return to England.

Boscawen returned to the

Boscawen returned to the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

and was commander-in-chief Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

during the trial of Admiral John Byng

Admiral John Byng (baptised 29 October 1704 – 14 March 1757) was a British Royal Navy officer who was court-martialled and executed by firing squad. After joining the navy at the age of thirteen, he participated at the Battle of Cape Pass ...

. Boscawen signed the order of execution after the King had refused to grant the unfortunate admiral a pardon. Boscawen was advanced to Senior Naval Lord on the Admiralty Board in November 1756 but then stood down (as Senior Naval Lord although he remained on the Board) in April 1757, during the caretaker ministry, before being advanced to Senior Naval Lord again in July 1757.

Siege of Louisburg

In October 1757 Boscawen was second in command under Admiral

In October 1757 Boscawen was second in command under Admiral Edward Hawke

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of T ...

. On 7 February 1758 Boscawen was promoted to Admiral of the blue squadron. and ordered to take a fleet to North America. Once there, he took naval command at the siege of Louisburg during June and July 1758. On this occasion rather than entrust the land assault to a naval commander, the army was placed under the command of General Jeffrey Amherst and Brigadier James Wolfe

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. ...

. The siege of Louisburg was one of the key contributors to the capture of French possessions in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. Wolfe later would use Louisburg as a staging point for the siege of Quebec. The capture of the town took away from the French the only effective naval base that they had in Canada, as well as leading to the destruction of four of their ships of the line and the capture of another. On his return from North America Boscawen was awarded the Thanks of both Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

for his service. The King made Boscawen a Privy Counsellor

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

in recognition for his continued service both as a member of the Board of Admiralty and commander-in-chief.

Battle of Lagos

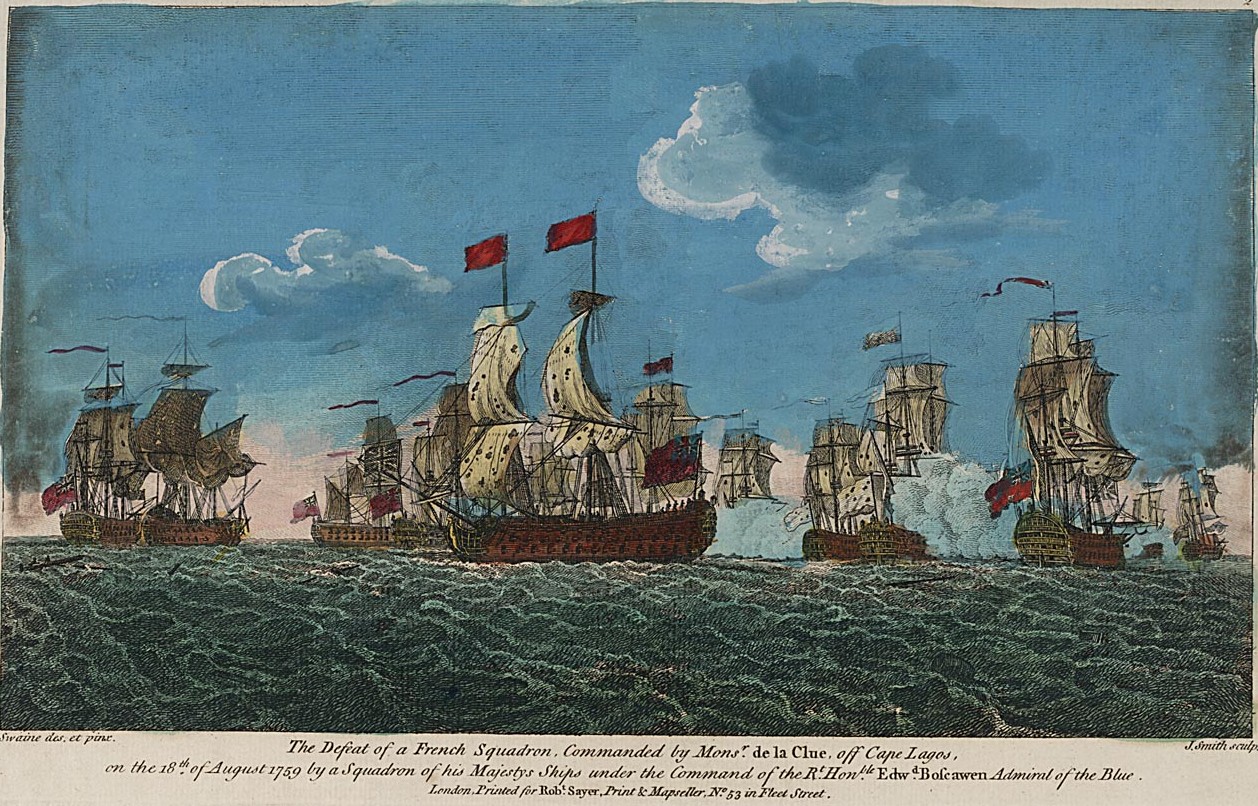

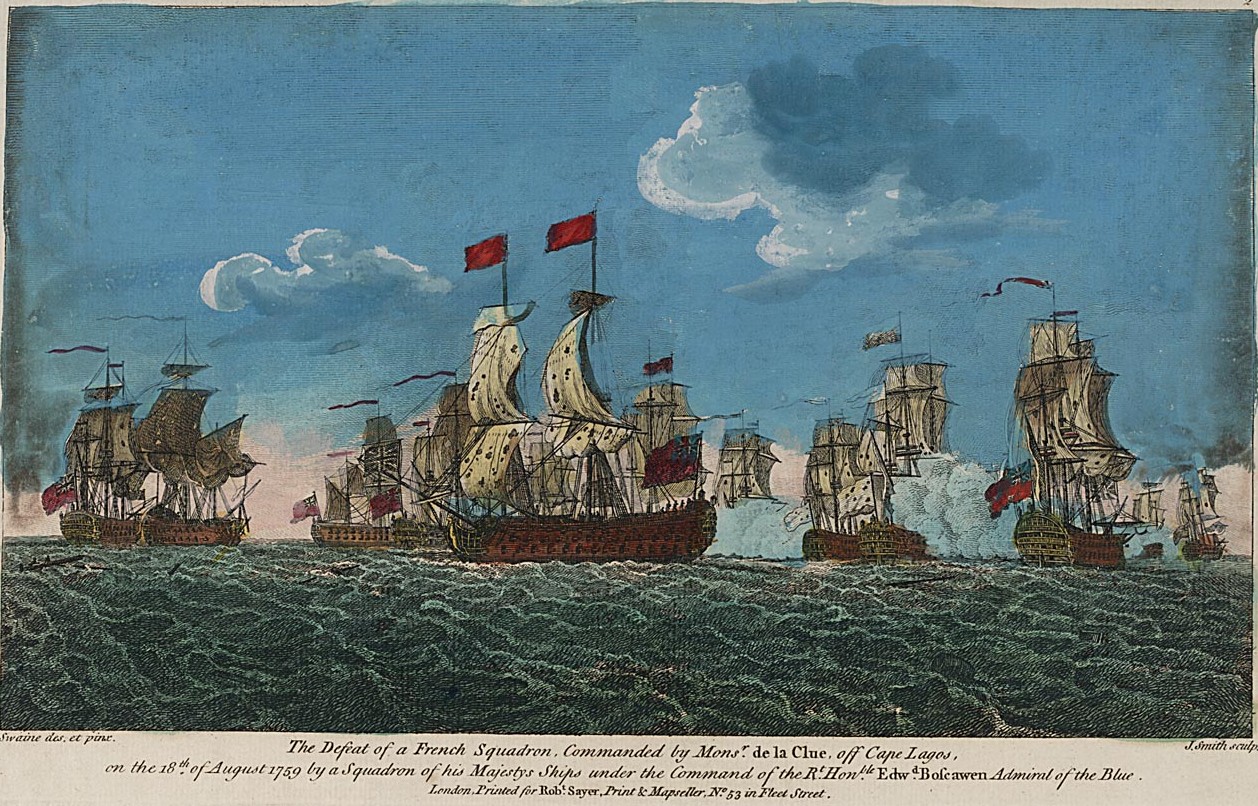

In April 1759 Boscawen took command of a fleet bound for the Mediterranean. His aim was to prevent another planned invasion of Britain by the French. With his flag aboard the newly constructed of 90 guns he blockaded

In April 1759 Boscawen took command of a fleet bound for the Mediterranean. His aim was to prevent another planned invasion of Britain by the French. With his flag aboard the newly constructed of 90 guns he blockaded Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

and kept the fleet of Admiral de le Clue-Sabran in port. In order to tempt the French out of port, Boscawen sent three of his ships to bombard the port. The guns of the batteries surrounding the town drove off the British ships. Having sustained damage in the action and due to the constant weathering of ships on blockade duty Boscawen took his fleet to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

to refit and resupply. On 17 August a frigate that had been ordered to watch the Straits of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaism, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to ...

signalled that the French fleet were in sight. Boscawen took his available ships to sea to engage de la Clue. During the night the British chased the French fleet and five of de la Clue's ships managed to separate from the fleet and escape. The others were driven in to a bay near Lagos

Lagos (Nigerian English: ; ) is the largest city in Nigeria and the second most populous city in Africa, with a population of 15.4 million as of 2015 within the city proper. Lagos was the national capital of Nigeria until December 1991 fo ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

. The British overhauled the remaining seven ships of the French fleet and engaged. The French line of battle ship began a duel with ''Namur'' but was outgunned and struck her colours. The damage aboard ''Namur'' forced Boscawen to shift his flag to of 80 guns. Whilst transferring between ships, the small boat that Boscawen was in was hit by an enemy cannonball. Boscawen took off his wig and plugged the hole. Two more French ships, and escaped during the second night and on the morning of 19 August the British captured and and drove the French flagship and ashore where they foundered and were set on fire by their crews to stop the British from taking them off and repairing them. The five French ships that avoided the battle made their way to Cadiz where Boscawen ordered Admiral Thomas Broderick to blockade the port.

Final years, death, and legacy

Boscawen returned to England, where he was promoted General of Marines in recognition of his service. He was given theFreedom of the City

The Freedom of the City (or Borough in some parts of the UK) is an honour bestowed by a municipality upon a valued member of the community, or upon a visiting celebrity or dignitary. Arising from the medieval practice of granting respected ...

of Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. Admiral Boscawen returned to sea for the final time and took his station off the west coast of France around Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (french: Baie de Quiberon) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to t ...

. After a violent attack of what was later diagnosed as Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

, the Admiral came ashore, where, on 10 January 1761, he died at his home in Hatchlands Park in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

. His body was taken to St. Michael's Church in St Michael Penkevil

St Michael Penkivel ( kw, Pennkevyl), sometimes spelt ''St Michael Penkevil'', is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is in the valley of the River Fal about three miles (5 km) southeast of Truro. The po ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

, where he was buried. The monument was designed by Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him. With his ...

and sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack

Johannes Michel or John Michael Rysbrack, original name Jan Michiel Rijsbrack, often referred to simply as Michael Rysbrack (24 June 1694 – 8 January 1770), was an 18th-century Flemish sculptor, who spent most of his career in England where h ...

. The monument at the church begins:

Here lies the Right Honourable

Edward Boscawen,

Admiral of the Blue, General of Marines,

Lord of the Admiralty, and one of his

Majesty's most Honourable Privy Council.

His birth, though noble,

His titles, though illustrious,

Were but incidental additions to his greatness.

Edward Boscawen,

Admiral of the Blue, General of Marines,

Lord of the Admiralty, and one of his

Majesty's most Honourable Privy Council.

His birth, though noble,

His titles, though illustrious,

Were but incidental additions to his greatness.

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

and Prime Minister once said to Boscawen: "When I apply to other Officers respecting any expedition I may chance to project, they always raise difficulties, you always find expedients."

Legacy

The town of Boscawen, New Hampshire is named after him. Two ships and a

The town of Boscawen, New Hampshire is named after him. Two ships and a stone frigate

A stone frigate is a naval establishment on land.

"Stone frigate" is an informal term that has its origin in Britain's Royal Navy after its use of Diamond Rock, an island off Martinique, as a 'sloop of war' to harass the French in 1803–04. ...

of the Royal Navy have borne the name HMS ''Boscawen'', after Admiral Boscawen, whilst another ship was planned but the plans were shelved before she was commissioned. The stone frigate was a training base for naval cadets and in consequence three ships were renamed HMS ''Boscawen'' whilst being used as the home base for the training establishment.

Quotes

Boscawen was quoted as saying "To be sure I lose the fruits of the earth, but then, I am gathering the flowers of the Sea" (1756) and "Never fire, my lads, till you see the whites of the Frenchmen's eyes."Frances Evelyn Boscawen

In 1742 Boscawen marriedFrances Evelyn Glanville

Frances Evelyn "Fanny" Boscawen (née Glanville) (23 July 1719 – 26 February 1805) was an English literary hostess, correspondent and member of the Blue Stockings Society. She was born Frances Evelyn Glanville on 23 July 1719 at St Clere, Kems ...

(1719–1805), with whom he had three sons and two daughters, and who became an important hostess of Bluestocking

''Bluestocking'' is a term for an educated, intellectual woman, originally a member of the 18th-century Blue Stockings Society from England led by the hostess and critic Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800), the "Queen of the Blues", including E ...

meetings after his death. The older daughter Frances married John Leveson-Gower, and the younger, Elizabeth married Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort.

References

Sources

* * * *External links

History of War – Siege of Louisburg 1758

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Boscawen, Edward 1711 births 1761 deaths Younger sons of viscounts Royal Navy admirals Lords of the Admiralty British military personnel of the French and Indian War Royal Navy personnel of the War of the Austrian Succession Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Truro British MPs 1741–1747 British MPs 1747–1754 British MPs 1754–1761 Burials in Cornwall

Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

18th-century English politicians

Sailors from Cornwall

British military personnel of the Anglo-Spanish War (1727–1729)

Royal Navy personnel of the Seven Years' War

People of Father Le Loutre's War