Edmond Halley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

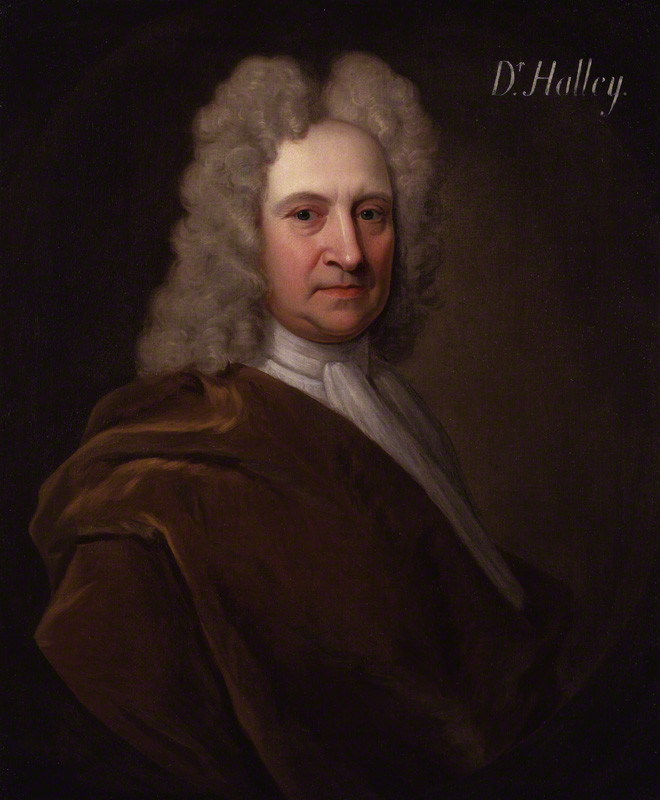

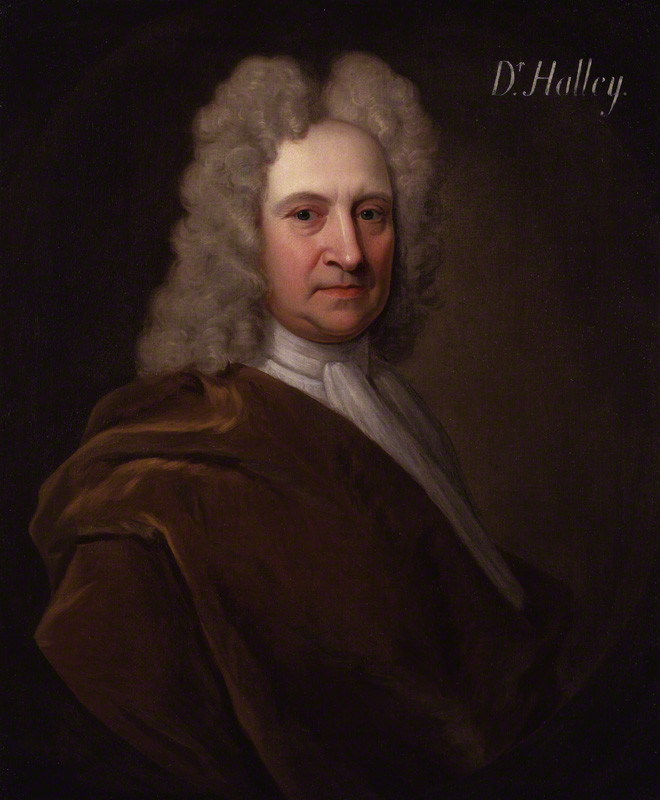

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English

In 1676, Flamsteed helped Halley publish his first paper, titled "A Direct and Geometrical Method of Finding the Aphelia, Eccentricities, and Proportions of the Primary Planets, Without Supposing Equality in Angular Motion", about planetary

In 1676, Flamsteed helped Halley publish his first paper, titled "A Direct and Geometrical Method of Finding the Aphelia, Eccentricities, and Proportions of the Primary Planets, Without Supposing Equality in Angular Motion", about planetary

In 1698, at the behest of King William III, Halley was given command of the , a

In 1698, at the behest of King William III, Halley was given command of the , a  The preface to Awnsham and John Churchill's collection of voyages and travels (1704), supposedly written by John Locke or by Halley, valourised expeditions such as these as part of a grand expansion of European knowledge of the world:

The preface to Awnsham and John Churchill's collection of voyages and travels (1704), supposedly written by John Locke or by Halley, valourised expeditions such as these as part of a grand expansion of European knowledge of the world:

Halley succeeded John Flamsteed in 1720 as Astronomer Royal, a position Halley held until his death in 1742 at the age of 85. He was buried in the graveyard of the old church of St Margaret's, Lee (since rebuilt), at Lee, London, Lee Terrace, Blackheath, London, Blackheath. He was interred in the same vault as the Astronomer Royal John Pond; the unmarked grave of the Astronomer Royal Nathaniel Bliss is nearby. His original tombstone was transferred by the British Admiralty, Admiralty when the original Lee church was demolished and rebuilt – it can be seen today on the southern wall of the Camera Obscura at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. His marked grave can be seen at St Margaret's Church, Lee Terrace.

Despite the persistent misconception that Halley received a knighthood, it is not the case. The idea can be tracked back to American astronomical texts such as William Augustus Norton's 1839 ''An Elementary Treatise on Astronomy'', possibly due to Halley's royal occupations and connections to Sir Isaac Newton.

Halley succeeded John Flamsteed in 1720 as Astronomer Royal, a position Halley held until his death in 1742 at the age of 85. He was buried in the graveyard of the old church of St Margaret's, Lee (since rebuilt), at Lee, London, Lee Terrace, Blackheath, London, Blackheath. He was interred in the same vault as the Astronomer Royal John Pond; the unmarked grave of the Astronomer Royal Nathaniel Bliss is nearby. His original tombstone was transferred by the British Admiralty, Admiralty when the original Lee church was demolished and rebuilt – it can be seen today on the southern wall of the Camera Obscura at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. His marked grave can be seen at St Margaret's Church, Lee Terrace.

Despite the persistent misconception that Halley received a knighthood, it is not the case. The idea can be tracked back to American astronomical texts such as William Augustus Norton's 1839 ''An Elementary Treatise on Astronomy'', possibly due to Halley's royal occupations and connections to Sir Isaac Newton.

* Halley's Comet (orbital period (approximately) 75 years)

* Halley (lunar crater)

* Halley (Martian crater)

* Halley Research Station, Antarctica

* Halley's method, for the numerical solution of equations

* Halley Street, in Blackburn, Victoria, Australia

* Edmund Halley Road, Oxford Science Park, Oxford, OX4 4DQ UK

* Edmund Halley Drive, Reston, Virginia, United States

* Edmund Halley Way, Greenwich Peninsula, London

* Halley's Mount, Saint Helena (680m high)

* Halley Drive, Hackensack, New Jersey, Hackensack, New Jersey, intersects with Comet Way on the campus of Hackensack High School, home of the Comets

* Rue Edmund Halley, Avignon, France

* The Halley Academy, a school in London, England

* Halley House School, Hackney London (2015)

* Halley Gardens, Blackheath, London.

* Halley's Comet (orbital period (approximately) 75 years)

* Halley (lunar crater)

* Halley (Martian crater)

* Halley Research Station, Antarctica

* Halley's method, for the numerical solution of equations

* Halley Street, in Blackburn, Victoria, Australia

* Edmund Halley Road, Oxford Science Park, Oxford, OX4 4DQ UK

* Edmund Halley Drive, Reston, Virginia, United States

* Edmund Halley Way, Greenwich Peninsula, London

* Halley's Mount, Saint Helena (680m high)

* Halley Drive, Hackensack, New Jersey, Hackensack, New Jersey, intersects with Comet Way on the campus of Hackensack High School, home of the Comets

* Rue Edmund Halley, Avignon, France

* The Halley Academy, a school in London, England

* Halley House School, Hackney London (2015)

* Halley Gardens, Blackheath, London.

Edmond Halley Biography (SEDS)

* The National Portrait Gallery (London) has several portraits of Halley

Search the collection

* Halley, Edmond

* Halley, Edmond

* ** Halley, Edmund

''A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets'' (1715)

annexed on pages 881 to 905 of volume 2 of ''The Elements of Astronomy'' by David Gregory * Material on Halley's life table for Breslau on the Life & Work of Statisticians site

* Halley, Edmund

Considerations on the Changes of the Latitudes of Some of the Principal Fixed Stars (1718)

– Reprinted in R. G. Aitken, ''Edmund Halley and Stellar Proper Motions'' (1942) *

Online catalogue of Halley's working papers (part of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives held at Cambridge University Library)

* Halley, Edmond (1724

"Some considerations about the cause of the universal deluge, laid before the Royal Society, on the 12th of December 1694"

an

"Some farther thoughts upon the same subject, delivered on the 19th of the same month"

''Philosophical Transactions, Giving Some Account of the Present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours of the Ingenious, in Many Considerable Parts of the World. Vol. 33'' p. 118–125. – digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library * {{DEFAULTSORT:Halley, Edmond 1656 births 1742 deaths 18th-century British astronomers Alumni of The Queen's College, Oxford Astronomers Royal British geophysicists British climatologists 17th-century English astronomers British scientific instrument makers English meteorologists English physicists Fellows of the Royal Society Halley's Comet Hollow Earth proponents People educated at St Paul's School, London People from Shoreditch Savilian Professors of Geometry English inventors Diving equipment inventors 17th-century English mathematicians 18th-century English mathematicians Royal Observatory, Greenwich

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either ...

, mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

and physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constit ...

in 1676–77, Halley catalogued the southern celestial hemisphere

The southern celestial hemisphere, also called the Southern Sky, is the southern half of the celestial sphere; that is, it lies south of the celestial equator. This arbitrary sphere, on which seemingly fixed stars form constellations, appear ...

and recorded a transit of Mercury across the Sun. He realised that a similar transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tr ...

could be used to determine the distances between Earth, Venus, and the Sun. Upon his return to England, he was made a fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

, and with the help of King Charles II, was granted a master's degree from Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

.

Halley encouraged and helped fund the publication of Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

's influential ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(English: ''Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'') often referred to as simply the (), is a book by Isaac Newton that expounds Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. The ''Principia'' is written in Latin and ...

'' (1687). From observations Halley made in September 1682, he used Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in mo ...

to compute the periodicity of Halley's Comet in his 1705 ''Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets''. It was named after him upon its predicted return in 1758, which he did not live to see.

Beginning in 1698, Halley made sailing expeditions and made observations on the conditions of terrestrial magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

. In 1718, he discovered the proper motion

Proper motion is the astrometric measure of the observed changes in the apparent places of stars or other celestial objects in the sky, as seen from the center of mass of the Solar System, compared to the abstract background of the more distan ...

of the "fixed" stars.

Early life

Halley was born in Haggerston inMiddlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

. According to Halley, his birthdate was . his father, Edmond Halley Sr., came from a Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

family and was a wealthy soap-maker in London. As a child, Halley was very interested in mathematics. He studied at St Paul's School, where he developed his initial interest in astronomy, and was elected captain of the school in 1671. On , Halley's mother, Anne Robinson, died. In July 1673, he began studying at The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassical architecture, ...

. Halley took a 24-foot-long telescope with him, apparently paid for by his father. While still an undergraduate, Halley published papers on the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

and sunspots

Sunspots are phenomena on the Sun's photosphere that appear as temporary spots that are darker than the surrounding areas. They are regions of reduced surface temperature caused by concentrations of magnetic flux that inhibit convection ...

. In March 1675, he wrote to John Flamsteed, the Astronomer Royal (England's first), telling him that the leading published tables on the positions of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

and Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

were erroneous, as were some of Tycho Brahe's star positions.

Career

Publications and inventions

In 1676, Flamsteed helped Halley publish his first paper, titled "A Direct and Geometrical Method of Finding the Aphelia, Eccentricities, and Proportions of the Primary Planets, Without Supposing Equality in Angular Motion", about planetary

In 1676, Flamsteed helped Halley publish his first paper, titled "A Direct and Geometrical Method of Finding the Aphelia, Eccentricities, and Proportions of the Primary Planets, Without Supposing Equality in Angular Motion", about planetary orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

s, in '' Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society''. Influenced by Flamsteed's project to compile a catalogue of stars of the northern celestial hemisphere, Halley proposed to do the same for the southern sky, dropping out of school to do so. He chose the south Atlantic island of Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constit ...

(west of Africa), from which he would be able to observe not only the southern stars, but also some of the northern stars with which to cross-reference them. King Charles II supported his endeavour. Halley sailed to the island in late 1676, then set up an observatory with a large sextant

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects. The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of ce ...

with telescopic sights. Over a year, he made observations with which he would produce the first catalogue of the southern sky, and observed a transit of Mercury across the Sun. Focusing on this latter observation, Halley realised that observing the solar parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby object ...

of a planet—more ideally using the transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tr ...

, which would not occur within his lifetime—could be used to trigonometrically determine the distances between Earth, Venus, and the Sun.Jeremiah Horrocks, William Crabtree, and the Lancashire observations of the transit of Venus of 1639, Allan Chapman 2004 Cambridge University Press

Halley returned to England in May 1678, and used his data to produce a map of the southern stars. Oxford would not allow Halley to return because he had violated his residency requirements when he left for Saint Helena. He appealed to Charles II, who signed a letter requesting that Halley be unconditionally awarded his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree, which the college granted on 3 December 1678. Just a few days before, Halley had been elected as a fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

, at the age of 22. In 1679, he published ''Catalogus Stellarum Australium'' ('A catalogue of the stars of the South'), which includes his map and descriptions of 341 stars. Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

presented the catalogue to the Royal Society. In mid-1679, Halley went to Danzig (Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

) on behalf of the Society to help resolve a dispute: because astronomer Johannes Hevelius

Johannes Hevelius

Some sources refer to Hevelius as Polish:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Some sources refer to Hevelius as German:

*

*

*

*

*of the Royal Society

* (in German also known as ''Hevel''; pl, Jan Heweliusz; – 28 January 1687) was a councillor ...

' observing instruments were not equipped with telescopic sight

A telescopic sight, commonly called a scope informally, is an optical sighting device based on a refracting telescope. It is equipped with some form of a referencing pattern – known as a '' reticle'' – mounted in a focally appropriate ...

s, Flamsteed and Hooke had questioned the accuracy of his observations; Halley stayed with Hevelius and checked his observations, finding that they were quite precise.

By 1681, Giovanni Domenico Cassini had told Halley of his theory that comets were objects in orbit. In September 1682, Halley carried out a series of observations of what became known as Halley's Comet; his name became associated with it because of his work on its orbit and predicting its return in 1758 (which he did not live to see). In early 1686, Halley was elected to the Royal Society's new position of secretary, requiring him to give up his fellowship and manage correspondence and meetings, as well as edit the ''Philosophical Transactions''. Also in 1686, Halley published the second part of the results from his Helenian expedition, being a paper and chart on trade winds and monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

s. The symbols he used to represent trailing winds still exist in most modern day weather chart representations. In this article he identified solar heating as the cause of atmospheric

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A ...

motions. He also established the relationship between barometric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars, 7 ...

and height above sea level. His charts were an important contribution to the emerging field of information visualisation.

Halley spent most of his time on lunar observations, but was also interested in the problems of gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

. One problem that attracted his attention was the proof of Kepler's laws of planetary motion

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler between 1609 and 1619, describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. The laws modified the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus, replacing its circular orb ...

. In August 1684, he went to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

to discuss this with Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

, much as John Flamsteed had done four years earlier, only to find that Newton had solved the problem, at the instigation of Flamsteed with regard to the orbit of comet Kirch, without publishing the solution. Halley asked to see the calculations and was told by Newton that he could not find them, but promised to redo them and send them on later, which he eventually did, in a short treatise titled '' On the motion of bodies in an orbit''. Halley recognised the importance of the work and returned to Cambridge to arrange its publication with Newton, who instead went on to expand it into his ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(English: ''Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'') often referred to as simply the (), is a book by Isaac Newton that expounds Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. The ''Principia'' is written in Latin and ...

'' published at Halley's expense in 1687. Halley's first calculations with comets were thereby for the orbit of comet Kirch, based on Flamsteed's observations in 1680–1681. Although he was to accurately calculate the orbit of the comet of 1682, he was inaccurate in his calculations of the orbit of comet Kirch. They indicated a periodicity of 575 years, thus appearing in the years 531 and 1106, and presumably heralding the death of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

in a like fashion in 45 BCE. It is now known to have an orbital period of circa 10,000 years.

In 1691, Halley built a diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

, a device in which the atmosphere was replenished by way of weighted barrels of air sent down from the surface. In a demonstration, Halley and five companions dived to in the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

, and remained there for over an hour and a half. Halley's bell was of little use for practical salvage work, as it was very heavy, but he made improvements to it over time, later extending his underwater exposure time to over 4 hours. Halley suffered one of the earliest recorded cases of middle ear barotrauma

Barotrauma is physical damage to body tissues caused by a difference in pressure between a gas space inside, or contact with, the body and the surrounding gas or liquid. The initial damage is usually due to over-stretching the tissues in tensi ...

. That same year, at a meeting of the Royal Society, Halley introduced a rudimentary working model of a magnetic compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

using a liquid-filled housing to damp the swing and wobble of the magnetised needle.

In 1691, Halley sought the post of Savilian Professor of Astronomy

The position of Savilian Professor of Astronomy was established at the University of Oxford in 1619. It was founded (at the same time as the Savilian Professorship of Geometry) by Sir Henry Savile, a mathematician and classical scholar who was ...

at Oxford. While a candidate for the position, Halley faced the animosity of the Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, and the Anglican Church questioned his religious views, largely on the grounds that he had doubted the Earth's age as given in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

. After Flamsteed wrote to Newton to rally support against Halley, Newton wrote back in hopes of reconciliation, but was unsuccessful. Halley's candidacy was opposed by both the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, John Tillotson, and Bishop Stillingfleet, and the post went instead to David Gregory, who had Newton's support.

In 1692, Halley put forth the idea of a hollow Earth

The Hollow Earth is a concept proposing that the planet Earth is entirely hollow or contains a substantial interior space. Notably suggested by Edmond Halley in the late 17th century, the notion was disproven, first tentatively by Pierre Bougue ...

consisting of a shell about 500 miles (800 km) thick, two inner concentric shells and an innermost core. He suggested that atmospheres separated these shells, and that each shell had its own magnetic poles, with each sphere rotating at a different speed. Halley proposed this scheme to explain anomalous compass readings. He envisaged each inner region as having an atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A ...

and being luminous (and possibly inhabited), and speculated that escaping gas caused the aurora borealis. He suggested, "Auroral rays are due to particles, which are affected by the magnetic field, the rays parallel to Earth's magnetic field."

In 1693 Halley published an article on life annuities, which featured an analysis of age-at-death on the basis of the Breslau statistics Caspar Neumann

Caspar (or Kaspar) Neumann (14 September 1648 – 27 January 1715) was a German professor and clergyman from Breslau with a special scientific interest in mortality rates.

Biography

Caspar Neuman was born September 14, 1648 in Breslau, to M ...

had been able to provide. This article allowed the British government to sell life annuities at an appropriate price based on the age of the purchaser. Halley's work strongly influenced the development of actuarial science. The construction of the life-table for Breslau, which followed more primitive work by John Graunt, is now seen as a major event in the history of demography

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as ed ...

.

The Royal Society censured Halley for suggesting in 1694 that the story of Noah's flood might be an account of a cometary impact. A similar theory was independently suggested three centuries later, but is generally rejected by geologists.Deutsch, A., C. Koeberl, J.D. Blum, B.M. French, B.P. Glass, R. Grieve, P. Horn, E.K. Jessberger, G. Kurat, W.U. Reimold, J. Smit, D. Stöffler, and S.R. Taylor, 1994, ''The impact-flood connection: Does it exist?'' Terra Nova. v. 6, pp. 644–650.

In 1696, Newton was appointed as warden of the Royal Mint and nominated Halley as deputy comptroller of the Chester mint. Halley spent two years supervising coin production. While there, he caught two clerks pilfering precious metals. He and the local warden spoke out about the scheme, unaware that the local master of the mint was profiting from it.

In 1698, the Czar of Russia (later known as Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

) was on a visit to England, and hoped Newton would be available to entertain him. Newton sent Halley in his place. He and the Czar bonded over science and brandy. According to one disputed account, when both of them were drunk one night, Halley jovially pushed the Czar around Deptford in a wheelbarrow.

Exploration years

In 1698, at the behest of King William III, Halley was given command of the , a

In 1698, at the behest of King William III, Halley was given command of the , a pink

Pink is the color of a namesake flower that is a pale tint of red. It was first used as a color name in the late 17th century. According to surveys in Europe and the United States, pink is the color most often associated with charm, politeness, ...

, so that he could carry out investigations in the South Atlantic into the laws governing the variation of the compass, as well as to refine the coordinates of the English colonies in the Americas. On 19 August 1698, he took command of the ship and, in November 1698, sailed on what was the first purely scientific voyage by an English naval vessel. Unfortunately problems of insubordination arose over questions of Halley's competence to command a vessel. Halley returned the ship to England to proceed against officers in July 1699. The result was a mild rebuke for his men, and dissatisfaction for Halley, who felt the court had been too lenient. Halley thereafter received a temporary commission as a captain in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, recommissioned the ''Paramour'' on 24 August 1699 and sailed again in September 1699 to make extensive observations on the conditions of terrestrial magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

. This task he accomplished in a second Atlantic voyage which lasted until 6 September 1700, and extended from 52 degrees north to 52 degrees south. The results were published in ''General Chart of the Variation of the Compass'' (1701). This was the first such chart to be published and the first on which isogonic, or Halleyan, lines appeared. The use of such lines inspired later ideas such as those of isotherms by Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister ...

in his maps. In 1701, Halley made a third and final voyage on the ''Paramour'' to study the tides of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

. In 1702, he was dispatched by Queen Anne on diplomatic missions to other European leaders.

The preface to Awnsham and John Churchill's collection of voyages and travels (1704), supposedly written by John Locke or by Halley, valourised expeditions such as these as part of a grand expansion of European knowledge of the world:

The preface to Awnsham and John Churchill's collection of voyages and travels (1704), supposedly written by John Locke or by Halley, valourised expeditions such as these as part of a grand expansion of European knowledge of the world:

What was cosmography before these discoveries, but an imperfect fragment of a science, scarce deserving so good a name? When all the known world was only Europe, a small part of Africk, and the lesser portion of Asia; so that of this terraqueous globe not one sixth part had ever been seen or heard of. Nay so great was the ignorance of man in this particular, that learned persons made a doubt of its being round; others no less knowing imagin'd all they were not acquainted with, desart and uninhabitable. But now geography and hydrography have receiv'd some perfection by the pains of so many mariners and travelers, who to evince the rotundity of the earth and water, have sail’d and travell'd round it, as has been here made appear; to show there is no part uninhabitable, unless the frozen polar regions, have visited all other countries, tho never so remote, which they have found well peopl'd, and most of them rich and delightful…. Astronomy has receiv'd the addition of many constellations never seen before. Natural and moral history is embelish'd with the most beneficial increase of so many thousands of plants it had never before receiv'd, so many drugs and spices, such variety of beasts, birds and fishes, such rarities in minerals, mountains and waters, such unaccountable diversity of climates and men, and in them of complexions, tempers, habits, manners, politicks, and religions…. To conclude, the empire of Europe is now extended to the utmost bounds of the earth, where several of its nations have conquests and colonies. These and many more are the advantages drawn from the labours of those, who expose themselves to the dangers of the vast ocean, and of unknown nations; which those who sit still at home abundantly reap in every kind: and the relation of one traveler is an incentive to stir up another to imitate him, whilst the rest of mankind, in their accounts without stirring a foot, compass the earth and seas, visit all countries, and converse with all nations.

Life as an academic

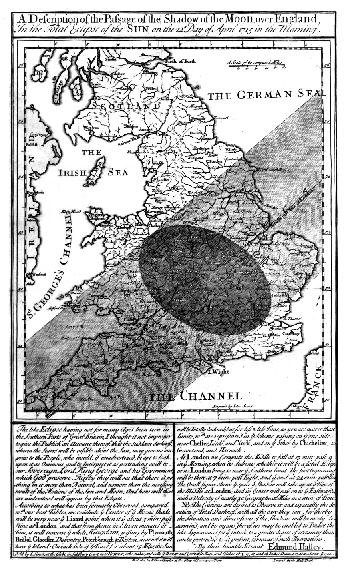

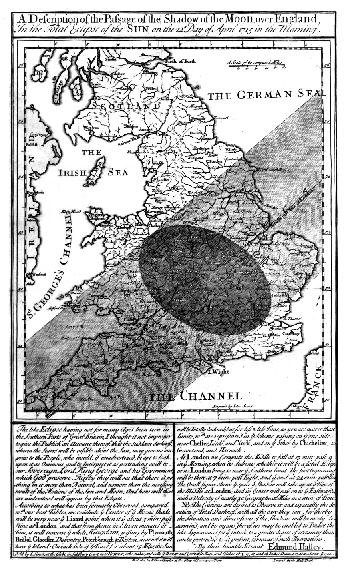

In November 1703, Halley was appointed Savilian Professor of Geometry at the University of Oxford, his theological enemies, John Tillotson and Bishop Stillingfleet having died. In 1705, applyinghistorical astronomy

Historical astronomy is the science of analysing historic astronomical data. The American Astronomical Society (AAS), established 1899, states that its Historical Astronomy Division "...shall exist for the purpose of advancing interest in topics r ...

methods, he published the paper '' Astronomiae cometicae synopsis'' (''A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets''); in this, he stated his belief that the comet sightings of 1456, 1531, 1607, and 1682 were of the same comet, and that it would return in 1758. Halley did not live to witness the comet's return, but when it did, the comet became generally known as Halley's Comet.

By 1706 Halley had learned Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

and completed the translation started by Edward Bernard of Books V–VII of Apollonius's ''Conics'' from copies found at Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration w ...

and the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the sec ...

at Oxford. He also completed a new translation of the first four books from the original Greek that had been started by the late David Gregory. He published these along with his own reconstruction of Book VIII in the first complete Latin edition in 1710. The same year, he received an honorary degree of doctor of laws from Oxford.

In 1716, Halley suggested a high-precision measurement of the distance between the Earth and the Sun by timing the transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tr ...

. In doing so, he was following the method described by James Gregory in ''Optica Promota'' (in which the design of the Gregorian telescope

The Gregorian telescope is a type of reflecting telescope designed by Scottish mathematician and astronomer James Gregory in the 17th century, and first built in 1673 by Robert Hooke. James Gregory was a contemporary of Isaac Newton. Both oft ...

is also described). It is reasonable to assume Halley possessed and had read this book given that the Gregorian design was the principal telescope design used in astronomy in Halley's day. It is not to Halley's credit that he failed to acknowledge Gregory's priority in this matter. In 1717–18 he discovered the proper motion

Proper motion is the astrometric measure of the observed changes in the apparent places of stars or other celestial objects in the sky, as seen from the center of mass of the Solar System, compared to the abstract background of the more distan ...

of the "fixed" stars (publishing this in 1718) by comparing his astrometric

Astrometry is a branch of astronomy that involves precise measurements of the positions and movements of stars and other celestial bodies. It provides the kinematics and physical origin of the Solar System and this galaxy, the Milky Way.

Hist ...

measurements with those given in Ptolemy's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it can ...

''. Arcturus and Sirius

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. Its name is derived from the Greek word , or , meaning 'glowing' or 'scorching'. The star is designated α Canis Majoris, Latinized to Alpha Canis Majoris, and abbreviated Alpha CM ...

were two noted to have moved significantly, the latter having progressed 30 arc minutes (about the diameter of the moon) southwards in 1800 years.

In 1720, together with his friend the antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

William Stukeley

William Stukeley (7 November 1687 – 3 March 1765) was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric ...

, Halley participated in the first attempt to scientifically date Stonehenge. Assuming that the monument had been laid out using a magnetic compass, Stukeley and Halley attempted to calculate the perceived deviation introducing corrections from existing magnetic records, and suggested three dates (460 BC, AD 220 and AD 920), the earliest being the one accepted. These dates were wrong by thousands of years, but the idea that scientific methods could be used to date ancient monuments was revolutionary in its day.

Halley succeeded John Flamsteed in 1720 as Astronomer Royal, a position Halley held until his death in 1742 at the age of 85. He was buried in the graveyard of the old church of St Margaret's, Lee (since rebuilt), at Lee, London, Lee Terrace, Blackheath, London, Blackheath. He was interred in the same vault as the Astronomer Royal John Pond; the unmarked grave of the Astronomer Royal Nathaniel Bliss is nearby. His original tombstone was transferred by the British Admiralty, Admiralty when the original Lee church was demolished and rebuilt – it can be seen today on the southern wall of the Camera Obscura at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. His marked grave can be seen at St Margaret's Church, Lee Terrace.

Despite the persistent misconception that Halley received a knighthood, it is not the case. The idea can be tracked back to American astronomical texts such as William Augustus Norton's 1839 ''An Elementary Treatise on Astronomy'', possibly due to Halley's royal occupations and connections to Sir Isaac Newton.

Halley succeeded John Flamsteed in 1720 as Astronomer Royal, a position Halley held until his death in 1742 at the age of 85. He was buried in the graveyard of the old church of St Margaret's, Lee (since rebuilt), at Lee, London, Lee Terrace, Blackheath, London, Blackheath. He was interred in the same vault as the Astronomer Royal John Pond; the unmarked grave of the Astronomer Royal Nathaniel Bliss is nearby. His original tombstone was transferred by the British Admiralty, Admiralty when the original Lee church was demolished and rebuilt – it can be seen today on the southern wall of the Camera Obscura at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. His marked grave can be seen at St Margaret's Church, Lee Terrace.

Despite the persistent misconception that Halley received a knighthood, it is not the case. The idea can be tracked back to American astronomical texts such as William Augustus Norton's 1839 ''An Elementary Treatise on Astronomy'', possibly due to Halley's royal occupations and connections to Sir Isaac Newton.

Personal life

Halley married Mary Tooke in 1682 and settled in Islington. The couple had three children.Named after Edmond Halley

* Halley's Comet (orbital period (approximately) 75 years)

* Halley (lunar crater)

* Halley (Martian crater)

* Halley Research Station, Antarctica

* Halley's method, for the numerical solution of equations

* Halley Street, in Blackburn, Victoria, Australia

* Edmund Halley Road, Oxford Science Park, Oxford, OX4 4DQ UK

* Edmund Halley Drive, Reston, Virginia, United States

* Edmund Halley Way, Greenwich Peninsula, London

* Halley's Mount, Saint Helena (680m high)

* Halley Drive, Hackensack, New Jersey, Hackensack, New Jersey, intersects with Comet Way on the campus of Hackensack High School, home of the Comets

* Rue Edmund Halley, Avignon, France

* The Halley Academy, a school in London, England

* Halley House School, Hackney London (2015)

* Halley Gardens, Blackheath, London.

* Halley's Comet (orbital period (approximately) 75 years)

* Halley (lunar crater)

* Halley (Martian crater)

* Halley Research Station, Antarctica

* Halley's method, for the numerical solution of equations

* Halley Street, in Blackburn, Victoria, Australia

* Edmund Halley Road, Oxford Science Park, Oxford, OX4 4DQ UK

* Edmund Halley Drive, Reston, Virginia, United States

* Edmund Halley Way, Greenwich Peninsula, London

* Halley's Mount, Saint Helena (680m high)

* Halley Drive, Hackensack, New Jersey, Hackensack, New Jersey, intersects with Comet Way on the campus of Hackensack High School, home of the Comets

* Rue Edmund Halley, Avignon, France

* The Halley Academy, a school in London, England

* Halley House School, Hackney London (2015)

* Halley Gardens, Blackheath, London.

Pronunciation and spelling

There are three pronunciations of the surname ''Halley''. These are , , and . As a personal surname, the most common pronunciation in the 21st century, both in Great Britain and in the United States, is (rhymes with "valley"). This is the personal pronunciation used by most Halleys living in London today. This is useful guidance but does not, of course, tell us how the name should be pronounced in the context of the astronomer or the comet. The alternative is much more common in the latter context than it is when used as a modern surname. Colin Ronan, one of Halley's biographers, preferred . Contemporary accounts spell his name ''Hailey, Hayley, Haley, Haly, Halley, Hawley'' and ''Hawly'', and presumably pronunciations varied similarly. As for his given name, although the spelling "Edmund" is quite common, "Edmond" is what Halley himself used, according to a 1902 article,''The Times'' (London) ''Notes and Queries'' No. 254, 8 November 1902 p.36 though a 2007 ''International Comet Quarterly'' article disputes this, commenting that in his published works, he used "Edmund" 22 times and "Edmond" only 3 times, with several other variations used as well, such as the Latinised "Edmundus". Much of the debate stems from the fact that, in Halley's own time, English spelling conventions were not yet standardised, and so he himself used multiple spellings.In popular media

* Halley is voiced by Cary Elwes in the 2014 documentary series ''Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey''. * A fictional version of Halley appears in ''The Magnus Archives'', a horror podcast. * Actor John Wood (English actor), John Wood was cast as Edmond Halley in the TV series, ''Longitude (TV serial), Longitude'' in 2000. * Halley is a major figure in David Williamson's play ''Nearer the Gods'', about Isaac Newton, Sir Isaac Newton * The pronunciation was used by rock and roll singer Bill Haley, who called his backing band his "Comets" after the common pronunciation of Halley's Comet in the United States at the time.See also

* History of geomagnetismNotes

References

Sources

* *Further reading

* * * * * *External links

Edmond Halley Biography (SEDS)

* The National Portrait Gallery (London) has several portraits of Halley

Search the collection

* Halley, Edmond

* Halley, Edmond

* ** Halley, Edmund

''A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets'' (1715)

annexed on pages 881 to 905 of volume 2 of ''The Elements of Astronomy'' by David Gregory * Material on Halley's life table for Breslau on the Life & Work of Statisticians site

* Halley, Edmund

Considerations on the Changes of the Latitudes of Some of the Principal Fixed Stars (1718)

– Reprinted in R. G. Aitken, ''Edmund Halley and Stellar Proper Motions'' (1942) *

Online catalogue of Halley's working papers (part of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives held at Cambridge University Library)

* Halley, Edmond (1724

"Some considerations about the cause of the universal deluge, laid before the Royal Society, on the 12th of December 1694"

an

"Some farther thoughts upon the same subject, delivered on the 19th of the same month"

''Philosophical Transactions, Giving Some Account of the Present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours of the Ingenious, in Many Considerable Parts of the World. Vol. 33'' p. 118–125. – digital facsimile from Linda Hall Library * {{DEFAULTSORT:Halley, Edmond 1656 births 1742 deaths 18th-century British astronomers Alumni of The Queen's College, Oxford Astronomers Royal British geophysicists British climatologists 17th-century English astronomers British scientific instrument makers English meteorologists English physicists Fellows of the Royal Society Halley's Comet Hollow Earth proponents People educated at St Paul's School, London People from Shoreditch Savilian Professors of Geometry English inventors Diving equipment inventors 17th-century English mathematicians 18th-century English mathematicians Royal Observatory, Greenwich