Earth's history on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Earth concerns the development of

The history of Earth concerns the development of

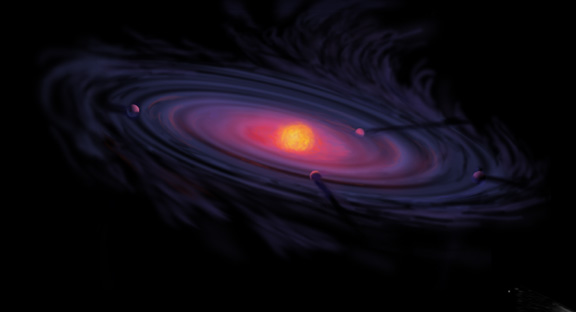

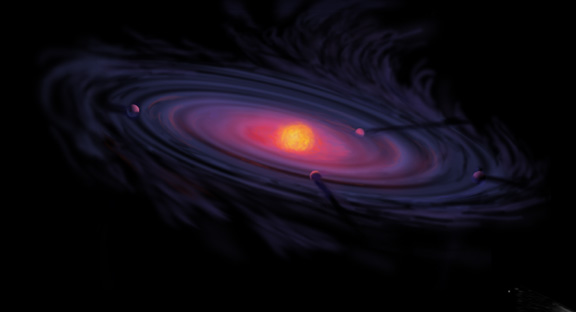

The standard model for the formation of the

The standard model for the formation of the

The first

The first

Earth's only

Earth's only

In early models for the formation of the atmosphere and ocean, the second atmosphere was formed by outgassing of

In early models for the formation of the atmosphere and ocean, the second atmosphere was formed by outgassing of

Another long-standing hypothesis is that the first life was composed of protein molecules. Amino acids, the building blocks of

Another long-standing hypothesis is that the first life was composed of protein molecules. Amino acids, the building blocks of

Research in 2003 reported that montmorillonite could also accelerate the conversion of

Research in 2003 reported that montmorillonite could also accelerate the conversion of

The earliest cells absorbed energy and food from the surrounding environment. They used

The earliest cells absorbed energy and food from the surrounding environment. They used  Photosynthesis had another major impact. Oxygen was toxic; much life on Earth probably died out as its levels rose in what is known as the '' oxygen catastrophe''. Resistant forms survived and thrived, and some developed the ability to use oxygen to increase their metabolism and obtain more energy from the same food.

Photosynthesis had another major impact. Oxygen was toxic; much life on Earth probably died out as its levels rose in what is known as the '' oxygen catastrophe''. Resistant forms survived and thrived, and some developed the ability to use oxygen to increase their metabolism and obtain more energy from the same food.

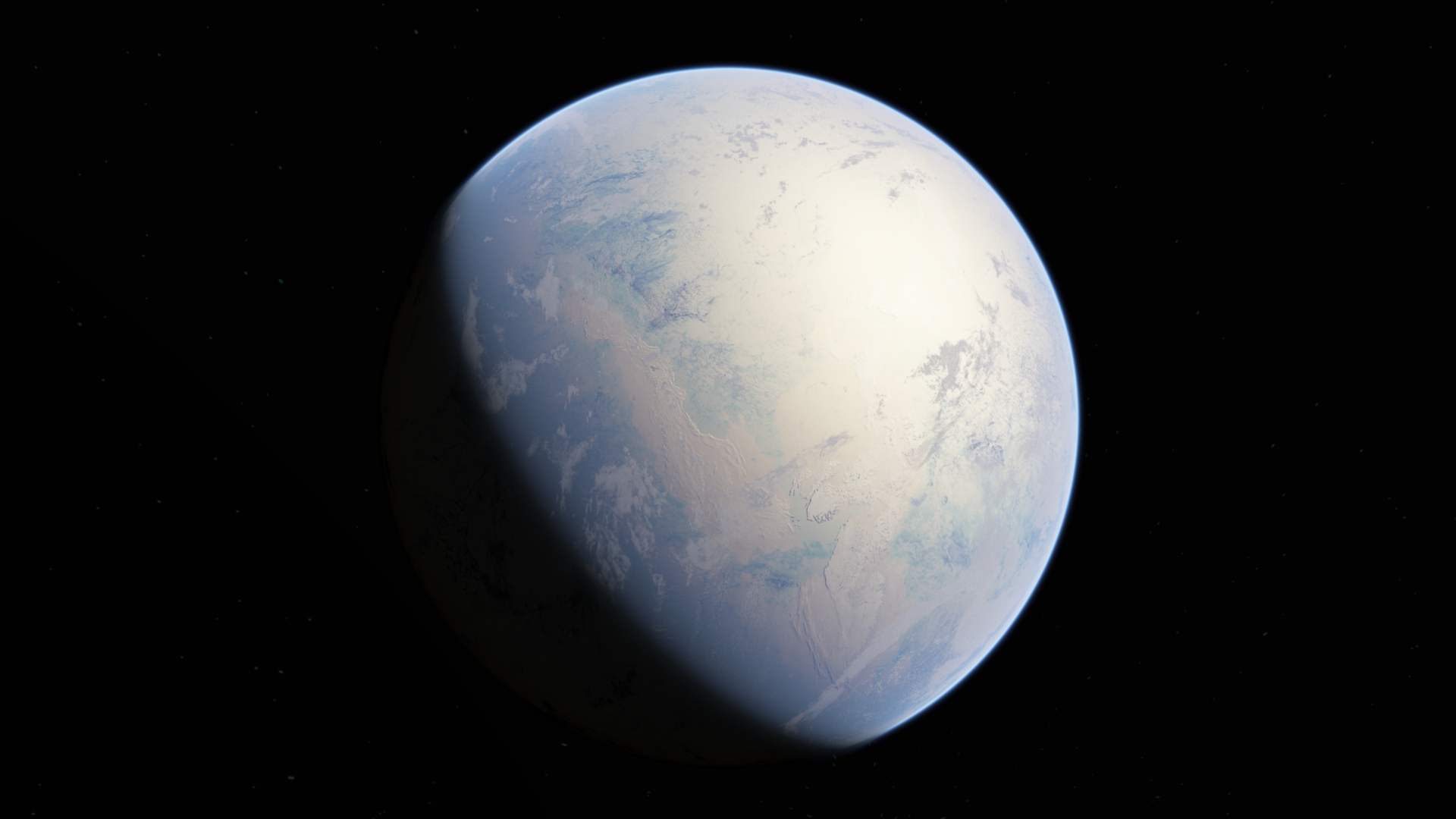

The natural evolution of the Sun made it progressively more luminous during the Archean and Proterozoic eons; the Sun's luminosity increases 6% every billion years. As a result, the Earth began to receive more heat from the Sun in the Proterozoic eon. However, the Earth did not get warmer. Instead, the geological record suggests it cooled dramatically during the early Proterozoic. Glacial deposits found in South Africa date back to 2.2 Ga, at which time, based on

The natural evolution of the Sun made it progressively more luminous during the Archean and Proterozoic eons; the Sun's luminosity increases 6% every billion years. As a result, the Earth began to receive more heat from the Sun in the Proterozoic eon. However, the Earth did not get warmer. Instead, the geological record suggests it cooled dramatically during the early Proterozoic. Glacial deposits found in South Africa date back to 2.2 Ga, at which time, based on

Modern

Modern

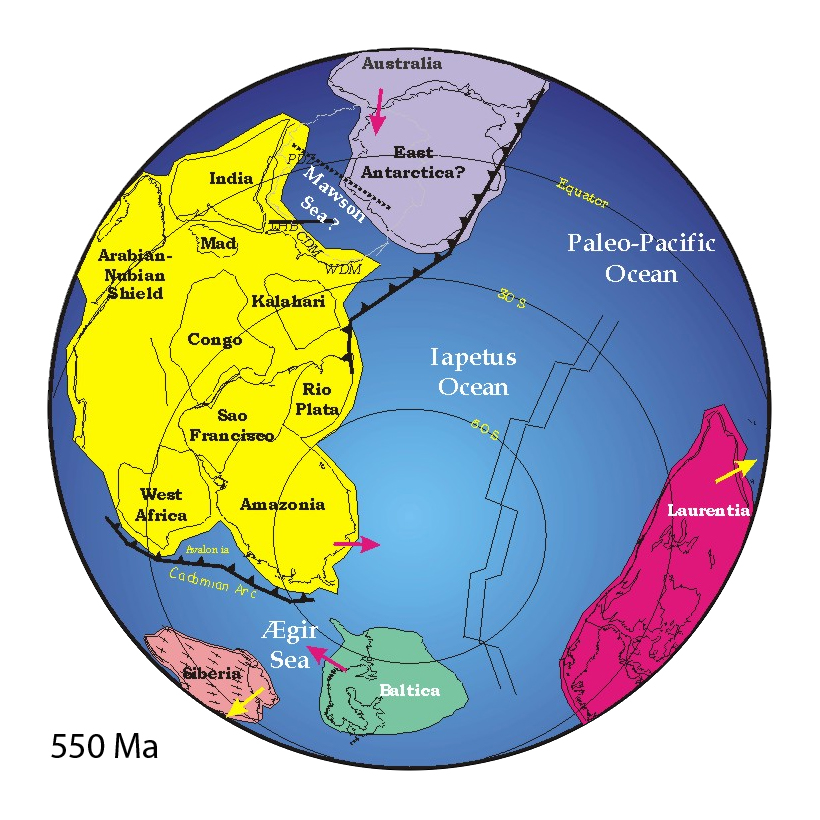

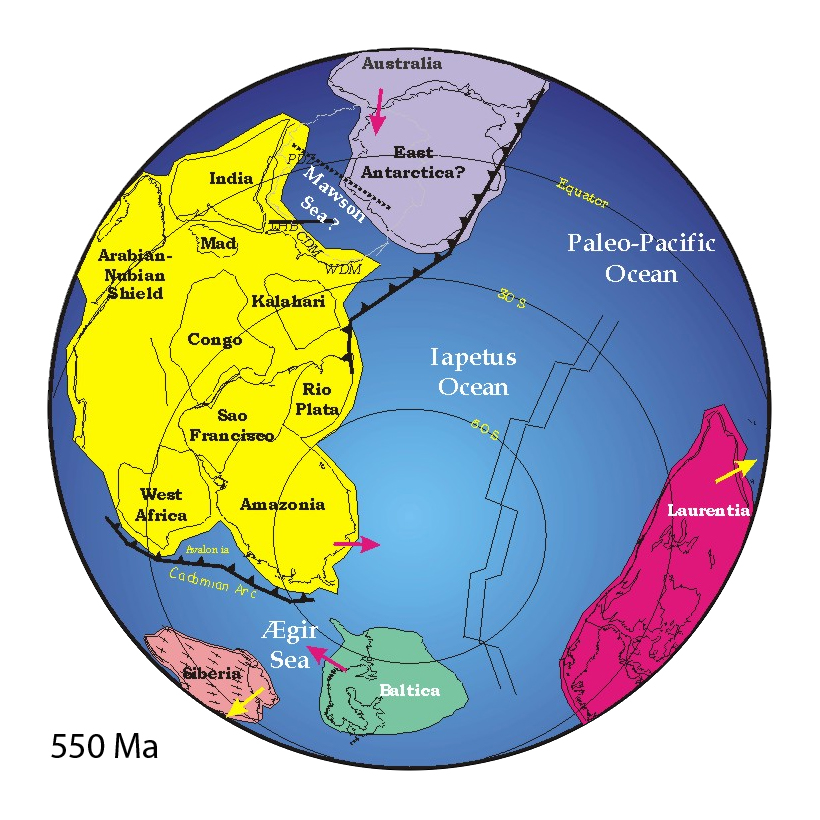

Reconstructions of tectonic plate movement in the past 250 million years (the Cenozoic and Mesozoic eras) can be made reliably using fitting of continental margins, ocean floor magnetic anomalies and paleomagnetic poles. No ocean crust dates back further than that, so earlier reconstructions are more difficult. Paleomagnetic poles are supplemented by geologic evidence such as

Reconstructions of tectonic plate movement in the past 250 million years (the Cenozoic and Mesozoic eras) can be made reliably using fitting of continental margins, ocean floor magnetic anomalies and paleomagnetic poles. No ocean crust dates back further than that, so earlier reconstructions are more difficult. Paleomagnetic poles are supplemented by geologic evidence such as

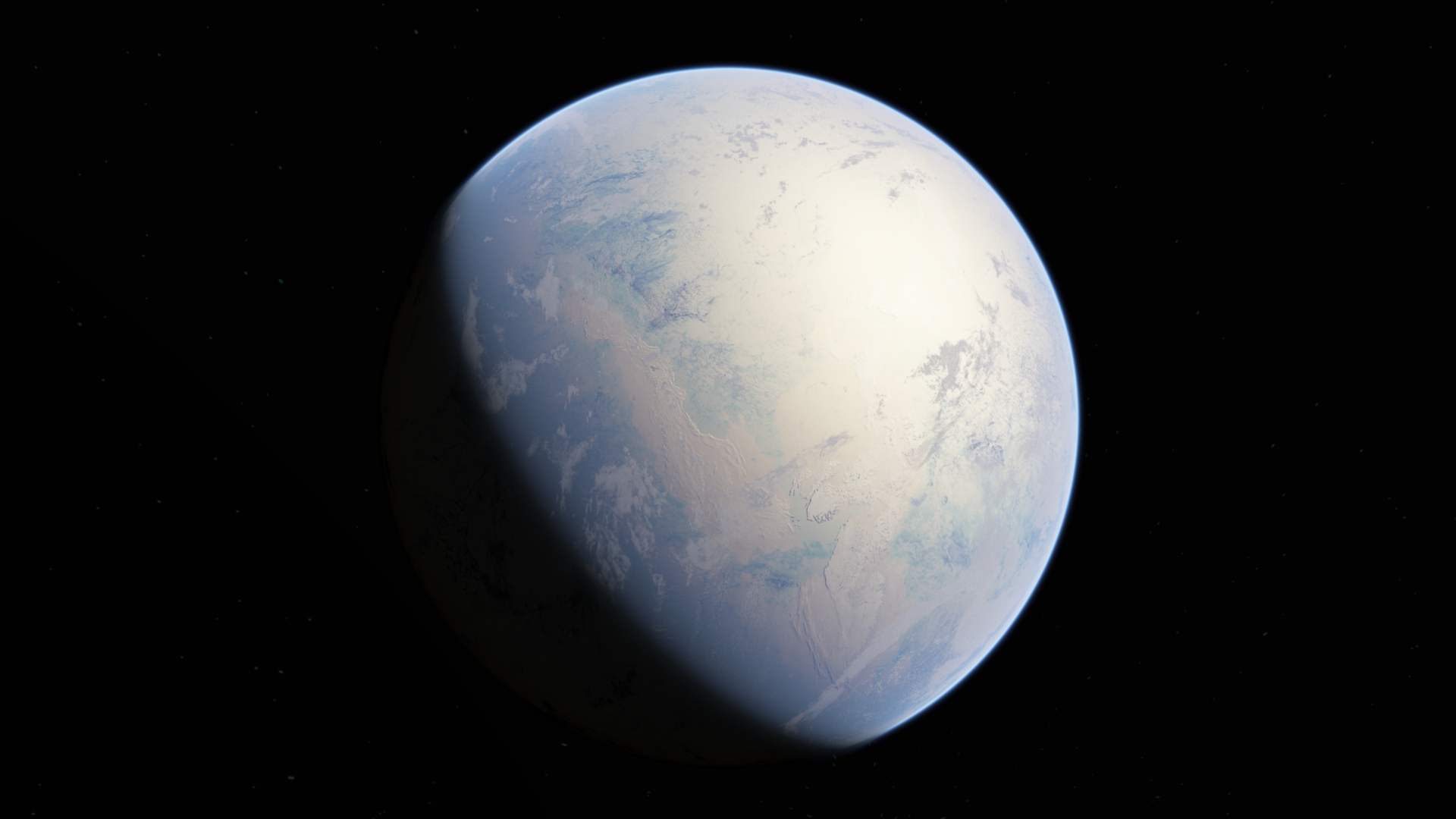

The end of the Proterozoic saw at least two Snowball Earths, so severe that the surface of the oceans may have been completely frozen. This happened about 716.5 and 635 Ma, in the Cryogenian period. The intensity and mechanism of both glaciations are still under investigation and harder to explain than the early Proterozoic Snowball Earth.

Most paleoclimatologists think the cold episodes were linked to the formation of the supercontinent Rodinia. Because Rodinia was centered on the equator, rates of

The end of the Proterozoic saw at least two Snowball Earths, so severe that the surface of the oceans may have been completely frozen. This happened about 716.5 and 635 Ma, in the Cryogenian period. The intensity and mechanism of both glaciations are still under investigation and harder to explain than the early Proterozoic Snowball Earth.

Most paleoclimatologists think the cold episodes were linked to the formation of the supercontinent Rodinia. Because Rodinia was centered on the equator, rates of

At the end of the Proterozoic, the supercontinent Pannotia had broken apart into the smaller continents Laurentia,

At the end of the Proterozoic, the supercontinent Pannotia had broken apart into the smaller continents Laurentia,

The rate of the evolution of life as recorded by fossils accelerated in the

The rate of the evolution of life as recorded by fossils accelerated in the

Oxygen accumulation from photosynthesis resulted in the formation of an ozone layer that absorbed much of the Sun's

Oxygen accumulation from photosynthesis resulted in the formation of an ozone layer that absorbed much of the Sun's

At the end of the Ordovician period, 443 Ma, additional

At the end of the Ordovician period, 443 Ma, additional  After yet another, the most severe extinction of the period (251~250 Ma), around 230 Ma, dinosaurs split off from their reptilian ancestors. The

After yet another, the most severe extinction of the period (251~250 Ma), around 230 Ma, dinosaurs split off from their reptilian ancestors. The

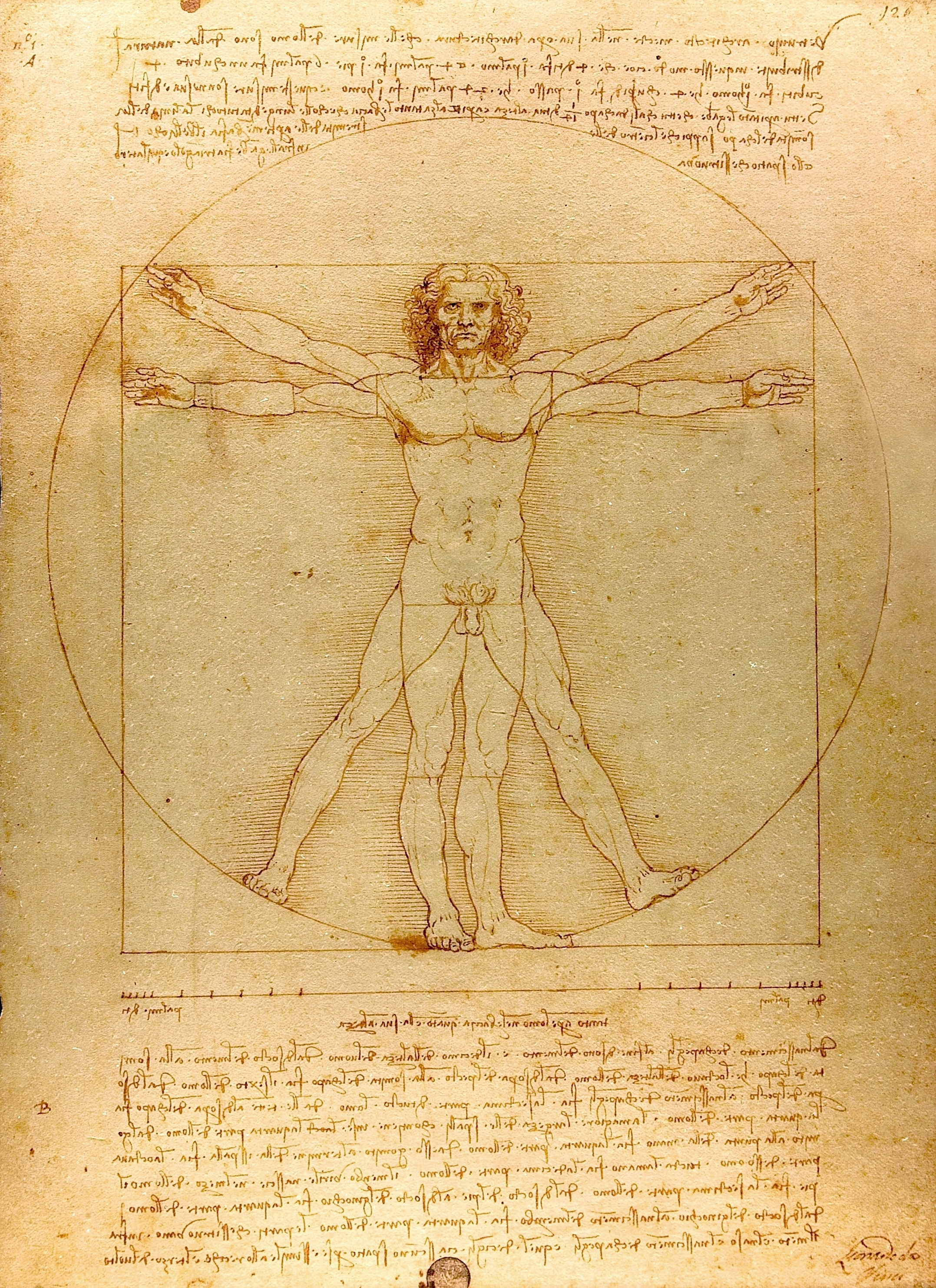

It is more difficult to establish the

It is more difficult to establish the

Throughout more than 90% of its history, ''Homo sapiens'' lived in small bands as

Throughout more than 90% of its history, ''Homo sapiens'' lived in small bands as

accessed 8 December 2014. p. (preface) Thomas E. Woods and Antonio Canizares, 2012, "How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization," Reprint edn., Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, , se

accessed 8 December 2014. p. 1: "Western civilization owes far more to Catholic Church than most people—Catholic included—often realize. The Church in fact built Western civilization."

/ref> In 610,

Change has continued at a rapid pace from the mid-1940s to today. Technological developments include

Change has continued at a rapid pace from the mid-1940s to today. Technological developments include

Quantum leap of life

. ''

Evolution timeline

(uses Flash Player). Animated story of life shows everything from the big bang to the formation of the Earth and the development of bacteria and other organisms to the ascent of man.

25 biggest turning points in Earth History

BBC

Evolution of the Earth

Timeline of the most important events in the evolution of the Earth. *

Ageing the Earth

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Richard Corfield, Hazel Rymer & Henry Gee (''In Our Time'', Nov. 20, 2003) {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Earth Earth Geochronology Geology theories * World history

planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a yo ...

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

from its formation to the present day. Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by constant geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

change and biological evolution

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

.

The geological time scale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochr ...

(GTS), as defined by international convention, depicts the large spans of time from the beginning of the Earth to the present, and its divisions chronicle some definitive events of Earth history. (In the graphic, Ma means "million years ago".) Earth formed around 4.54 billion years ago, approximately one-third the age of the universe

In physical cosmology, the age of the universe is the time elapsed since the Big Bang. Astronomers have derived two different measurements of the age of the universe:

a measurement based on direct observations of an early state of the universe ...

, by accretion

Accretion may refer to:

Science

* Accretion (astrophysics), the formation of planets and other bodies by collection of material through gravity

* Accretion (meteorology), the process by which water vapor in clouds forms water droplets around nucl ...

from the solar nebula

The formation of the Solar System began about 4.6 billion years ago with the gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant molecular cloud. Most of the collapsing mass collected in the center, forming the Sun, while the rest flattened into ...

. Volcanic outgassing

Outgassing (sometimes called offgassing, particularly when in reference to indoor air quality) is the release of a gas that was dissolved, trapped, frozen, or absorbed in some material. Outgassing can include sublimation and evaporation (which a ...

probably created the primordial atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

and then the ocean, but the early atmosphere contained almost no oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

. Much of the Earth was molten because of frequent collisions with other bodies which led to extreme volcanism. While the Earth was in its earliest stage (Early Earth

The early Earth is loosely defined as Earth in its first one billion years, or gigayear (Ga, 109y). The “early Earth” encompasses approximately the first gigayear in the evolution of our planet, from its initial formation in the young Solar Sy ...

), a giant impact collision with a planet-sized body named Theia

In Greek mythology, Theia (; grc, Θεία, Theía, divine, also rendered Thea or Thia), also called Euryphaessa ( grc, Εὐρυφάεσσα) "wide-shining", is one of the twelve Titans, the children of the earth goddess Gaia and the sky god ...

is thought to have formed the Moon. Over time, the Earth cooled, causing the formation of a solid crust, and allowing liquid water on the surface.

The Hadean

The Hadean ( ) is a geologic eon of Earth history preceding the Archean. On Earth, the Hadean began with the planet's formation about 4.54 billion years ago (although the start of the Hadean is defined as the age of the oldest solid materi ...

eon represents the time before a reliable (fossil) record of life; it began with the formation of the planet and ended 4.0 billion years ago. The following Archean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth during the Archea ...

and Proterozoic

The Proterozoic () is a geological eon spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8million years ago. It is the most recent part of the Precambrian "supereon". It is also the longest eon of the Earth's geologic time scale, and it is subdivided ...

eons produced the beginnings of life on Earth and its earliest evolution

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

. The succeeding eon is the Phanerozoic

The Phanerozoic Eon is the current geologic eon in the geologic time scale, and the one during which abundant animal and plant life has existed. It covers 538.8 million years to the present, and it began with the Cambrian Period, when anim ...

, divided into three eras: the Palaeozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ''z ...

, an era of arthropods, fishes, and the first life on land; the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

, which spanned the rise, reign, and climactic extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs; and the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configurat ...

, which saw the rise of mammals. Recognizable humans emerged at most 2 million years ago, a vanishingly small period on the geological scale.

The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates at least from 3.5 billion years ago, during the Eoarchean Era, after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean

The Hadean ( ) is a geologic eon of Earth history preceding the Archean. On Earth, the Hadean began with the planet's formation about 4.54 billion years ago (although the start of the Hadean is defined as the age of the oldest solid materi ...

Eon

Eon or Eons may refer to: Time

* Aeon, an indefinite long period of time

* Eon (geology), a division of the geologic time scale

Arts and entertainment

Fictional characters

* Eon, in the 2007 film '' Ben 10: Race Against Time''

* Eon, in th ...

. There are microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet of microorganisms, mainly bacteria and archaea, or bacteria alone. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few survive in desert ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s such as stromatolites

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). The ...

found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

discovered in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

. Other early physical evidence of a biogenic substance

A biogenic substance is a product made by or of life forms. While the term originally was specific to metabolite compounds that had toxic effects on other organisms, it has developed to encompass any constituents, secretions, and metabolites of p ...

is graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on lar ...

in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks

In geology, metasedimentary rock is a type of metamorphic rock. Such a rock was first formed through the deposition and solidification of sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and ...

discovered in southwestern Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

as well as "remains of biotic life" found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia. Early edition, published online before print. According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth … then it could be common in the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

."

Photosynthetic

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

organisms appeared between 3.2 and 2.4 billion years ago and began enriching the atmosphere with oxygen. Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

remained mostly small and microscopic until about 580 million years ago, when complex multicellular life arose, developed over time, and culminated in the Cambrian Explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil recor ...

about 538.8 million years ago. This sudden diversification of life forms produced most of the major phyla known today, and divided the Proterozoic Eon from the Cambrian Period of the Paleozoic Era. It is estimated that 99 percent of all species that ever lived on Earth, over five billion, have gone extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

. Estimates on the number of Earth's current species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

range from 10 million to 14 million, of which about 1.2 million are documented, but over 86 percent have not been described. However, it was recently claimed that 1 trillion species currently live on Earth, with only one-thousandth of one percent described.

The Earth's crust has constantly changed since its formation, as has life since its first appearance. Species continue to evolve, taking on new forms, splitting into daughter species, or going extinct in the face of ever-changing physical environments. The process of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

continues to shape the Earth's continents and oceans and the life they harbor.

Eons

Ingeochronology

Geochronology is the science of determining the age of rocks, fossils, and sediments using signatures inherent in the rocks themselves. Absolute geochronology can be accomplished through radioactive isotopes, whereas relative geochronology is p ...

, time is generally measured in mya (million years ago), each unit representing the period of approximately 1,000,000 years in the past. The history of Earth is divided into four great eons, starting 4,540 mya with the formation of the planet. Each eon saw the most significant changes in Earth's composition, climate and life. Each eon is subsequently divided into eras

Eras is a humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Albert Boton and Albert Hollenstein and was released by the International Typeface Corporation (ITC) in 1976. Eras is licensed by the Linotype type foundry.

A distinct and curious feature of E ...

, which in turn are divided into periods, which are further divided into epochs

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

.

Geologic time scale

The history of the Earth can be organized chronologically according to thegeologic time scale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochr ...

, which is split into intervals based on stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers ( strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithostra ...

analysis.

Solar System formation

The standard model for the formation of the

The standard model for the formation of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

(including the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

) is the solar nebula hypothesis. In this model, the Solar System formed from a large, rotating cloud of interstellar dust and gas called the solar nebula

The formation of the Solar System began about 4.6 billion years ago with the gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant molecular cloud. Most of the collapsing mass collected in the center, forming the Sun, while the rest flattened into ...

. It was composed of hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxi ...

and helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table ...

created shortly after the Big Bang

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from the ...

13.8 Ga (billion years ago) and heavier elements

Element or elements may refer to:

Science

* Chemical element, a pure substance of one type of atom

* Heating element, a device that generates heat by electrical resistance

* Orbital elements, parameters required to identify a specific orbit of o ...

ejected by supernovae

A supernova is a powerful and luminous explosion of a star. It has the plural form supernovae or supernovas, and is abbreviated SN or SNe. This transient astronomical event occurs during the last evolutionary stages of a massive star or when ...

. About 4.5 Ga, the nebula began a contraction that may have been triggered by the shock wave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a med ...

from a nearby supernova

A supernova is a powerful and luminous explosion of a star. It has the plural form supernovae or supernovas, and is abbreviated SN or SNe. This transient astronomical event occurs during the last evolutionary stages of a massive star or whe ...

. A shock wave would have also made the nebula rotate. As the cloud began to accelerate, its angular momentum

In physics, angular momentum (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a conserved quantity—the total angular momentum of a closed syste ...

, gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the str ...

, and inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law ...

flattened it into a protoplanetary disk

A protoplanetary disk is a rotating circumstellar disc of dense gas and dust surrounding a young newly formed star, a T Tauri star, or Herbig Ae/Be star. The protoplanetary disk may also be considered an accretion disk for the star itself, b ...

perpendicular to its axis of rotation. Small perturbations due to collisions and the angular momentum of other large debris created the means by which kilometer-sized protoplanet

A protoplanet is a large planetary embryo that originated within a protoplanetary disc and has undergone internal melting to produce a differentiated interior. Protoplanets are thought to form out of kilometer-sized planetesimals that gravitation ...

s began to form, orbiting the nebular center.

The center of the nebula, not having much angular momentum, collapsed rapidly, the compression heating it until nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles (neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manife ...

of hydrogen into helium began. After more contraction, a T Tauri star

T Tauri stars (TTS) are a class of variable stars that are less than about ten million years old. This class is named after the prototype, T Tauri, a young star in the Taurus star-forming region. They are found near molecular clouds and ide ...

ignited and evolved into the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

. Meanwhile, in the outer part of the nebula gravity caused matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic parti ...

to condense around density perturbations and dust particles, and the rest of the protoplanetary disk began separating into rings. In a process known as runaway accretion

Accretion may refer to:

Science

* Accretion (astrophysics), the formation of planets and other bodies by collection of material through gravity

* Accretion (meteorology), the process by which water vapor in clouds forms water droplets around nucl ...

, successively larger fragments of dust and debris clumped together to form planets. Earth formed in this manner about 4.54 billion years ago (with an uncertainty

Uncertainty refers to epistemic situations involving imperfect or unknown information. It applies to predictions of future events, to physical measurements that are already made, or to the unknown. Uncertainty arises in partially observable o ...

of 1%) and was largely completed within 10–20 million years. The solar wind

The solar wind is a stream of charged particles released from the upper atmosphere of the Sun, called the corona. This plasma mostly consists of electrons, protons and alpha particles with kinetic energy between . The composition of the sol ...

of the newly formed T Tauri star cleared out most of the material in the disk that had not already condensed into larger bodies. The same process is expected to produce accretion disks

An accretion disk is a structure (often a circumstellar disk) formed by diffuse material in orbital motion around a massive central body. The central body is typically a star. Friction, uneven irradiance, magnetohydrodynamic effects, and other ...

around virtually all newly forming stars in the universe, some of which yield planets

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a yo ...

.

The proto-Earth grew by accretion until its interior was hot enough to melt the heavy, siderophile metal

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typica ...

s. Having higher densities than the silicates, these metals sank. This so-called '' iron catastrophe'' resulted in the separation of a primitive mantle and a (metallic) core only 10 million years after the Earth began to form, producing the layered structure of Earth

The internal structure of Earth is the solid portion of the Earth, excluding its atmosphere and hydrosphere. The structure consists of an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous asthenosphere and solid mantle, a liquid outer core whose ...

and setting up the formation of Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic ...

. J.A. Jacobs was the first to suggest that Earth's inner core

Earth's inner core is the innermost geologic layer of planet Earth. It is primarily a solid ball with a radius of about , which is about 20% of Earth's radius or 70% of the Moon's radius.

There are no samples of Earth's core accessible for d ...

—a solid center distinct from the liquid outer core

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. The outer core begins approximately beneath Earth's surface at the core-mantle boundary and e ...

—is freezing

Freezing is a phase transition where a liquid turns into a solid when its temperature is lowered below its freezing point. In accordance with the internationally established definition, freezing means the solidification phase change of a liquid o ...

and growing out of the liquid outer core due to the gradual cooling of Earth's interior (about 100 degrees Celsius per billion years).

Hadean and Archean Eons

The first

The first eon

Eon or Eons may refer to: Time

* Aeon, an indefinite long period of time

* Eon (geology), a division of the geologic time scale

Arts and entertainment

Fictional characters

* Eon, in the 2007 film '' Ben 10: Race Against Time''

* Eon, in th ...

in Earth's history, the ''Hadean'', begins with the Earth's formation and is followed by the ''Archean'' eon at 3.8 Ga. The oldest rocks found on Earth date to about 4.0 Ga, and the oldest detrital

Detritus (; adj. ''detrital'' ) is particles of rock derived from pre-existing rock through weathering and erosion.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Ed, Stephen Marshak, p G-7 A fragment of detritus is called a clast.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Ed, Steph ...

zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of the ...

crystals in rocks to about 4.4 Ga, soon after the formation of the Earth's crust and the Earth itself. The giant impact hypothesis

The giant-impact hypothesis, sometimes called the Big Splash, or the Theia Impact, suggests that the Moon formed from the ejecta of a collision between the proto-Earth and a Mars-sized planet, approximately 4.5 billion years ago, in the Hadean ...

for the Moon's formation states that shortly after formation of an initial crust, the proto-Earth was impacted by a smaller protoplanet, which ejected part of the mantle and crust into space and created the Moon.

From crater counts on other celestial bodies, it is inferred that a period of intense meteorite impacts, called the ''Late Heavy Bombardment

The Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB), or lunar cataclysm, is a hypothesized event thought to have occurred approximately 4.1 to 3.8 billion years (Ga) ago, at a time corresponding to the Neohadean and Eoarchean eras on Earth. According to the hypot ...

'', began about 4.1 Ga, and concluded around 3.8 Ga, at the end of the Hadean. In addition, volcanism was severe due to the large heat flow

Heat transfer is a discipline of thermal engineering that concerns the generation, use, conversion, and exchange of thermal energy ( heat) between physical systems. Heat transfer is classified into various mechanisms, such as thermal conductio ...

and geothermal gradient

Geothermal gradient is the rate of temperature change with respect to increasing depth in Earth's interior. As a general rule, the crust temperature rises with depth due to the heat flow from the much hotter mantle; away from tectonic plate b ...

. Nevertheless, detrital zircon crystals dated to 4.4 Ga show evidence of having undergone contact with liquid water, suggesting that the Earth already had oceans or seas at that time.

By the beginning of the Archean, the Earth had cooled significantly. Present life forms could not have survived at Earth's surface, because the Archean atmosphere lacked oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

hence had no ozone layer

The ozone layer or ozone shield is a region of Earth's stratosphere that absorbs most of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation. It contains a high concentration of ozone (O3) in relation to other parts of the atmosphere, although still small in relat ...

to block ultraviolet light. Nevertheless, it is believed that primordial life began to evolve by the early Archean, with candidate fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s dated to around 3.5 Ga. Some scientists even speculate that life could have begun during the early Hadean, as far back as 4.4 Ga, surviving the possible Late Heavy Bombardment period in hydrothermal vents below the Earth's surface.

Formation of the Moon

Earth's only

Earth's only natural satellite

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moo ...

, the Moon, is larger relative to its planet than any other satellite in the Solar System. During the Apollo program, rocks from the Moon's surface were brought to Earth. Radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares ...

of these rocks shows that the Moon is 4.53 ± 0.01 billion years old, formed at least 30 million years after the Solar System. New evidence suggests the Moon formed even later, 4.48 ± 0.02 Ga, or 70–110 million years after the start of the Solar System.

Theories for the formation of the Moon must explain its late formation as well as the following facts. First, the Moon has a low density (3.3 times that of water, compared to 5.5 for the Earth) and a small metallic core. Second, the Earth and Moon have the same oxygen isotopic signature

An isotopic signature (also isotopic fingerprint) is a ratio of non-radiogenic ' stable isotopes', stable radiogenic isotopes, or unstable radioactive isotopes of particular elements in an investigated material. The ratios of isotopes in a sample ...

(relative abundance of the oxygen isotopes). Of the theories proposed to account for these phenomena, one is widely accepted: The ''giant impact hypothesis'' proposes that the Moon originated after a body the size of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin atm ...

(sometimes named Theia

In Greek mythology, Theia (; grc, Θεία, Theía, divine, also rendered Thea or Thia), also called Euryphaessa ( grc, Εὐρυφάεσσα) "wide-shining", is one of the twelve Titans, the children of the earth goddess Gaia and the sky god ...

) struck the proto-Earth a glancing blow.

The collision released about 100 million times more energy than the more recent Chicxulub impact

The Chicxulub crater () is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore near the community of Chicxulub, after which it is named. It was formed slightly over 66 million years ago when a large as ...

that is believed to have caused the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs. It was enough to vaporize some of the Earth's outer layers and melt both bodies. A portion of the mantle material was ejected

Ejection or Eject may refer to:

* Ejection (sports), the act of officially removing someone from a game

* Eject (''Transformers''), a fictional character from ''The Transformers'' television series

* "Eject" (song), 1993 rap rock single by Senser ...

into orbit around the Earth. The giant impact hypothesis predicts that the Moon was depleted of metallic material, explaining its abnormal composition. The ejecta in orbit around the Earth could have condensed into a single body within a couple of weeks. Under the influence of its own gravity, the ejected material became a more spherical body: the Moon.

First continents

Mantle convection

Mantle convection is the very slow creeping motion of Earth's solid silicate mantle as convection currents carrying heat from the interior to the planet's surface.

The Earth's surface lithosphere rides atop the asthenosphere and the two form ...

, the process that drives plate tectonics, is a result of heat flow from the Earth's interior to the Earth's surface. It involves the creation of rigid tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

s at mid-oceanic ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a diver ...

s. These plates are destroyed by subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

into the mantle at subduction zone

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

s. During the early Archean (about 3.0 Ga) the mantle was much hotter than today, probably around , so convection in the mantle was faster. Although a process similar to present-day plate tectonics did occur, this would have gone faster too. It is likely that during the Hadean and Archean, subduction zones were more common, and therefore tectonic plates were smaller.

The initial crust, formed when the Earth's surface first solidified, totally disappeared from a combination of this fast Hadean plate tectonics and the intense impacts of the Late Heavy Bombardment. However, it is thought that it was basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low- viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron ( mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More tha ...

ic in composition, like today's oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic c ...

, because little crustal differentiation had yet taken place. The first larger pieces of continental crust

Continental crust is the layer of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks that forms the geological continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as continental shelves. This layer is sometimes called ''sial'' bec ...

, which is a product of differentiation of lighter elements during partial melting

Partial melting occurs when only a portion of a solid is melted. For mixed substances, such as a rock containing several different minerals or a mineral that displays solid solution, this melt can be different from the bulk composition of the solid ...

in the lower crust, appeared at the end of the Hadean, about 4.0 Ga. What is left of these first small continents are called craton

A craton (, , or ; from grc-gre, κράτος "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging and ...

s. These pieces of late Hadean and early Archean crust form the cores around which today's continents grew.

The oldest rocks on Earth are found in the North American craton

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' i ...

of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world ...

. They are tonalite

Tonalite is an igneous, plutonic ( intrusive) rock, of felsic composition, with phaneritic (coarse-grained) texture. Feldspar is present as plagioclase (typically oligoclase or andesine) with alkali feldspar making up less than 10% of the tot ...

s from about 4.0 Ga. They show traces of metamorphism

Metamorphism is the transformation of existing rock (the protolith) to rock with a different mineral composition or texture. Metamorphism takes place at temperatures in excess of , and often also at elevated pressure or in the presence of ch ...

by high temperature, but also sedimentary grains that have been rounded by erosion during transport by water, showing that rivers and seas existed then. Cratons consist primarily of two alternating types of terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its own ...

s. The first are so-called greenstone belt

Greenstone belts are zones of variably metamorphosed mafic to ultramafic volcanic sequences with associated sedimentary rocks that occur within Archaean and Proterozoic cratons between granite and gneiss bodies.

The name comes from the green h ...

s, consisting of low-grade metamorphosed sedimentary rocks. These "greenstones" are similar to the sediments today found in oceanic trench

Oceanic trenches are prominent long, narrow topographic depressions of the ocean floor. They are typically wide and below the level of the surrounding oceanic floor, but can be thousands of kilometers in length. There are about of oceanic tre ...

es, above subduction zones. For this reason, greenstones are sometimes seen as evidence for subduction during the Archean. The second type is a complex of felsic

In geology, felsic is a modifier describing igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz.Marshak, Stephen, 2009, ''Essentials of Geology,'' W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. It is contrasted with mafic rocks, whi ...

magmatic rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or ...

s. These rocks are mostly tonalite, trondhjemite

Trondhjemite is a leucocratic (light-colored) intrusive igneous rock. It is a variety of tonalite in which the plagioclase is mostly in the form of oligoclase. Trondhjemites that occur in the oceanic crust or in ophiolites are usually called p ...

or granodiorite

Granodiorite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock similar to granite, but containing more plagioclase feldspar than orthoclase feldspar.

The term banatite is sometimes used informally for various rocks ranging from gr ...

, types of rock similar in composition to granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies unde ...

(hence such terranes are called TTG-terranes). TTG-complexes are seen as the relicts

A relict is a surviving remnant of a natural phenomenon.

Biology

A relict (or relic) is an organism that at an earlier time was abundant in a large area but now occurs at only one or a few small areas.

Geology and geomorphology

In geology, a r ...

of the first continental crust, formed by partial melting in basalt.

Oceans and atmosphere

Earth is often described as having had three atmospheres. The first atmosphere, captured from the solar nebula, was composed of light ( atmophile) elements from the solar nebula, mostly hydrogen and helium. A combination of the solar wind and Earth's heat would have driven off this atmosphere, as a result of which the atmosphere is now depleted of these elements compared to cosmic abundances. After the impact which created the Moon, the molten Earth released volatile gases; and later more gases were released byvolcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

es, completing a second atmosphere rich in greenhouse gas

A greenhouse gas (GHG or GhG) is a gas that absorbs and emits radiant energy within the thermal infrared range, causing the greenhouse effect. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere are water vapor (), carbon dioxide (), methane ...

es but poor in oxygen. Finally, the third atmosphere, rich in oxygen, emerged when bacteria began to produce oxygen about 2.8 Ga.

In early models for the formation of the atmosphere and ocean, the second atmosphere was formed by outgassing of

In early models for the formation of the atmosphere and ocean, the second atmosphere was formed by outgassing of volatiles

Volatiles are the group of chemical elements and chemical compounds that can be readily vaporized. In contrast with volatiles, elements and compounds that are not readily vaporized are known as refractory substances.

On planet Earth, the term ...

from the Earth's interior. Now it is considered likely that many of the volatiles were delivered during accretion by a process known as ''impact degassing'' in which incoming bodies vaporize on impact. The ocean and atmosphere would, therefore, have started to form even as the Earth formed. The new atmosphere probably contained water vapor

(99.9839 °C)

, -

, Boiling point

,

, -

, specific gas constant

, 461.5 J/( kg·K)

, -

, Heat of vaporization

, 2.27 MJ/kg

, -

, Heat capacity

, 1.864 kJ/(kg·K)

Water vapor, water vapour or aqueous vapor is the gaseous phas ...

, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and smaller amounts of other gases.

Planetesimals at a distance of 1 astronomical unit

The astronomical unit (symbol: au, or or AU) is a unit of length, roughly the distance from Earth to the Sun and approximately equal to or 8.3 light-minutes. The actual distance from Earth to the Sun varies by about 3% as Earth orbits ...

(AU), the distance of the Earth from the Sun, probably did not contribute any water to the Earth because the solar nebula was too hot for ice to form and the hydration of rocks by water vapor would have taken too long. The water must have been supplied by meteorites from the outer asteroid belt and some large planetary embryos from beyond 2.5 AU. Comets may also have contributed. Though most comets are today in orbits farther away from the Sun than Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 time ...

, computer simulations show that they were originally far more common in the inner parts of the Solar System.

As the Earth cooled, clouds formed. Rain created the oceans. Recent evidence suggests the oceans may have begun forming as early as 4.4 Ga. By the start of the Archean eon, they already covered much of the Earth. This early formation has been difficult to explain because of a problem known as the faint young Sun paradox. Stars are known to get brighter as they age, and the Sun has become 30% brighter since its formation 4.5 billion years ago. Many models indicate that the early Earth should have been covered in ice. A likely solution is that there was enough carbon dioxide and methane to produce a greenhouse effect

The greenhouse effect is a process that occurs when energy from a planet's host star goes through the planet's atmosphere and heats the planet's surface, but greenhouse gases in the atmosphere prevent some of the heat from returning directly ...

. The carbon dioxide would have been produced by volcanoes and the methane by early microbes. It is hypothesized that there also existed an organic haze created from the products of methane photolysis that caused an anti-greenhouse effect as well. Another greenhouse gas, ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous w ...

, would have been ejected by volcanos but quickly destroyed by ultraviolet radiation.

Origin of life

One of the reasons for interest in the early atmosphere and ocean is that they form the conditions under which life first arose. There are many models, but little consensus, on how life emerged from non-living chemicals; chemical systems created in the laboratory fall well short of the minimum complexity for a living organism. The first step in the emergence of life may have been chemical reactions that produced many of the simpler organic compounds, includingnucleobases

Nucleobases, also known as ''nitrogenous bases'' or often simply ''bases'', are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic ...

and amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

, that are the building blocks of life. An experiment in 1953 by Stanley Miller

Stanley Lloyd Miller (March 7, 1930 – May 20, 2007) was an American chemist who made landmark experiments in the origin of life by demonstrating that a wide range of vital organic compounds can be synthesized by fairly simple chemical process ...

and Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the d ...

showed that such molecules could form in an atmosphere of water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen with the aid of sparks to mimic the effect of lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

. Although atmospheric composition was probably different from that used by Miller and Urey, later experiments with more realistic compositions also managed to synthesize organic molecules. Computer simulation

Computer simulation is the process of mathematical modelling, performed on a computer, which is designed to predict the behaviour of, or the outcome of, a real-world or physical system. The reliability of some mathematical models can be det ...

s show that extraterrestrial organic molecules could have formed in the protoplanetary disk before the formation of the Earth.

Additional complexity could have been reached from at least three possible starting points: self-replication

Self-replication is any behavior of a dynamical system that yields construction of an identical or similar copy of itself. Biological cells, given suitable environments, reproduce by cell division. During cell division, DNA is replicated and c ...

, an organism's ability to produce offspring that are similar to itself; metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

, its ability to feed and repair itself; and external cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

s, which allow food to enter and waste products to leave, but exclude unwanted substances.

Replication first: RNA world

Even the simplest members of the three modern domains of life use DNA to record their "recipes" and a complex array ofRNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

and protein molecules to "read" these instructions and use them for growth, maintenance, and self-replication.

The discovery that a kind of RNA molecule called a ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozymes demon ...

can catalyze

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

both its own replication and the construction of proteins led to the hypothesis that earlier life-forms were based entirely on RNA. They could have formed an RNA world

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

in which there were individuals but no species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

, as mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s and horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HG ...

s would have meant that the offspring in each generation were quite likely to have different genomes

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

from those that their parents started with. RNA would later have been replaced by DNA, which is more stable and therefore can build longer genomes, expanding the range of capabilities a single organism can have. Ribozymes remain as the main components of ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to fo ...

s, the "protein factories" of modern cells.

Although short, self-replicating RNA molecules have been artificially produced in laboratories, doubts have been raised about whether natural non-biological synthesis of RNA is possible. The earliest ribozymes may have been formed of simpler nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

s such as PNA, TNA or GNA, which would have been replaced later by RNA. Other pre-RNA replicators have been posited, including crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macr ...

s and even quantum systems.

In 2003 it was proposed that porous metal sulfide precipitate

In an aqueous solution, precipitation is the process of transforming a dissolved substance into an insoluble solid from a super-saturated solution. The solid formed is called the precipitate. In case of an inorganic chemical reaction leading ...

s would assist RNA synthesis at about and at ocean-bottom pressures near hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

s. In this hypothesis, the proto-cells would be confined in the pores of the metal substrate until the later development of lipid membranes.

Metabolism first: iron–sulfur world

proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

, are easily synthesized in plausible prebiotic conditions, as are small peptides

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A ...

(polymers

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic and ...

of amino acids) that make good catalysts. A series of experiments starting in 1997 showed that amino acids and peptides could form in the presence of carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simp ...

and hydrogen sulfide with iron sulfide

Iron sulfide or Iron sulphide can refer to range of chemical compounds composed of iron and sulfur.

Minerals

By increasing order of stability:

* Iron(II) sulfide, FeS

* Greigite, Fe3S4 (cubic)

* Pyrrhotite, Fe1−xS (where x = 0 to 0.2) (monoclin ...

and nickel sulfide as catalysts. Most of the steps in their assembly required temperatures of about and moderate pressures, although one stage required and a pressure equivalent to that found under of rock. Hence, self-sustaining synthesis of proteins could have occurred near hydrothermal vents.

A difficulty with the metabolism-first scenario is finding a way for organisms to evolve. Without the ability to replicate as individuals, aggregates of molecules would have "compositional genomes" (counts of molecular species in the aggregate) as the target of natural selection. However, a recent model shows that such a system is unable to evolve in response to natural selection.

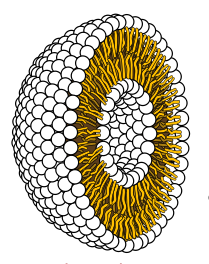

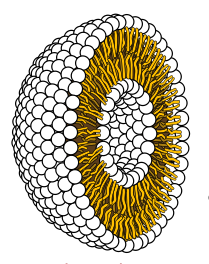

Membranes first: Lipid world

It has been suggested that double-walled "bubbles" oflipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids includ ...

s like those that form the external membranes of cells may have been an essential first step. Experiments that simulated the conditions of the early Earth have reported the formation of lipids, and these can spontaneously form liposome

A liposome is a small artificial vesicle, spherical in shape, having at least one lipid bilayer. Due to their hydrophobicity and/or hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, particle size and many other properties, liposomes can be used as drug deliver ...

s, double-walled "bubbles", and then reproduce themselves. Although they are not intrinsically information-carriers as nucleic acids are, they would be subject to natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Char ...

for longevity and reproduction. Nucleic acids such as RNA might then have formed more easily within the liposomes than they would have outside.

The clay theory

Someclay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay parti ...

s, notably montmorillonite

Montmorillonite is a very soft phyllosilicate group of minerals that form when they precipitate from water solution as microscopic crystals, known as clay. It is named after Montmorillon in France. Montmorillonite, a member of the smectite gro ...

, have properties that make them plausible accelerators for the emergence of an RNA world: they grow by self-replication of their crystalline pattern, are subject to an analog of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Char ...

(as the clay "species" that grows fastest in a particular environment rapidly becomes dominant), and can catalyze the formation of RNA molecules. Although this idea has not become the scientific consensus, it still has active supporters.

Research in 2003 reported that montmorillonite could also accelerate the conversion of

Research in 2003 reported that montmorillonite could also accelerate the conversion of fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is ...

s into "bubbles", and that the bubbles could encapsulate RNA attached to the clay. Bubbles can then grow by absorbing additional lipids and dividing. The formation of the earliest cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

may have been aided by similar processes.

A similar hypothesis presents self-replicating iron-rich clays as the progenitors of nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecule ...

s, lipids and amino acids.

Last universal common ancestor

It is believed that of this multiplicity of protocells, only oneline

Line most often refers to:

* Line (geometry), object with zero thickness and curvature that stretches to infinity

* Telephone line, a single-user circuit on a telephone communication system

Line, lines, The Line, or LINE may also refer to:

Art ...

survived. Current phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

evidence suggests that the last universal ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; t ...

(LUA) lived during the early Archean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth during the Archea ...

eon, perhaps 3.5 Ga or earlier. This LUA cell is the ancestor of all life on Earth today. It was probably a prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

, possessing a cell membrane and probably ribosomes, but lacking a nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

or membrane-bound organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s such as mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is u ...

or chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s. Like modern cells, it used DNA as its genetic code, RNA for information transfer and protein synthesis

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via degradation or export) through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critical ...

, and enzymes to catalyze reactions. Some scientists believe that instead of a single organism being the last universal common ancestor, there were populations of organisms exchanging genes by lateral gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

.

Proterozoic Eon

The Proterozoic eon lasted from 2.5 Ga to 538.8 Ma (million years) ago. In this time span,cratons

A craton (, , or ; from grc-gre, κράτος "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging and ...

grew into continents with modern sizes. The change to an oxygen-rich atmosphere was a crucial development. Life developed from prokaryotes into eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bact ...

s and multicellular forms. The Proterozoic saw a couple of severe ice ages called snowball Earth

The Snowball Earth hypothesis proposes that, during one or more of Earth's icehouse climates, the planet's surface became entirely or nearly entirely frozen. It is believed that this occurred sometime before 650 M.Y.A. (million years ago) du ...

s. After the last Snowball Earth about 600 Ma, the evolution of life on Earth accelerated. About 580 Ma, the Ediacaran biota

The Ediacaran (; formerly Vendian) biota is a taxonomic period classification that consists of all life forms that were present on Earth during the Ediacaran Period (). These were composed of enigmatic tubular and frond-shaped, mostly sessi ...

formed the prelude for the Cambrian Explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil recor ...

.

Oxygen revolution

The earliest cells absorbed energy and food from the surrounding environment. They used

The earliest cells absorbed energy and food from the surrounding environment. They used fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

, the breakdown of more complex compounds into less complex compounds with less energy, and used the energy so liberated to grow and reproduce. Fermentation can only occur in an ''anaerobic'' (oxygen-free) environment. The evolution of photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in ...

made it possible for cells to derive energy from the Sun.

Most of the life that covers the surface of the Earth depends directly or indirectly on photosynthesis. The most common form, oxygenic photosynthesis, turns carbon dioxide, water, and sunlight into food. It captures the energy of sunlight in energy-rich molecules such as ATP, which then provide the energy to make sugars. To supply the electrons in the circuit, hydrogen is stripped from water, leaving oxygen as a waste product. Some organisms, including purple bacteria

Purple bacteria or purple photosynthetic bacteria are Gram-negative proteobacteria that are phototrophic, capable of producing their own food via photosynthesis. They are pigmented with bacteriochlorophyll ''a'' or ''b'', together with various ...

and green sulfur bacteria

The green sulfur bacteria are a phylum of obligately anaerobic photoautotrophic bacteria that metabolize sulfur.

Green sulfur bacteria are nonmotile (except ''Chloroherpeton thalassium'', which may glide) and capable of anoxygenic photosynth ...

, use an anoxygenic form of photosynthesis that uses alternatives to hydrogen stripped from water as electron donors

In chemistry, an electron donor is a chemical entity that donates electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process.

Typical reducing agents undergo permanent chemi ...

; examples are hydrogen sulfide, sulfur and iron. Such extremophile

An extremophile (from Latin ' meaning "extreme" and Greek ' () meaning "love") is an organism that is able to live (or in some cases thrive) in extreme environments, i.e. environments that make survival challenging such as due to extreme temper ...

organisms are restricted to otherwise inhospitable environments such as hot springs and hydrothermal vents.

The simpler anoxygenic form arose about 3.8 Ga, not long after the appearance of life. The timing of oxygenic photosynthesis is more controversial; it had certainly appeared by about 2.4 Ga, but some researchers put it back as far as 3.2 Ga. The latter "probably increased global productivity by at least two or three orders of magnitude". Among the oldest remnants of oxygen-producing lifeforms are fossil stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). The ...

s.

At first, the released oxygen was bound up with limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

, iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in fro ...