Eugenicist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a

The term ''eugenics'' and its modern field of study were first formulated by

The term ''eugenics'' and its modern field of study were first formulated by

The reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany.

The reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany.

One general concern that the reduced

One general concern that the reduced

The novel ''

The novel ''The film ''

H-Eugenics, H-Net's network on the history of eugenics

from

Eugenics: Its Origin and Development (1883–Present)

by the

Eugenics and Scientific Racism Fact Sheet

by the

human population

In world demographics, the world population is the total number of humans currently alive. It was estimated by the United Nations to have exceeded eight billion in mid-November 2022. It took around 300,000 years of human prehistory and histor ...

. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological properti ...

by inhibiting the fertility of those considered inferior, or promoting that of those considered superior.

The contemporary history of eugenics

The history of eugenics is the study of development and advocacy of ideas related to eugenics around the world. Early eugenic ideas were discussed in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, Rome. The height of the modern eugenics movement came in the la ...

began in the late 19th century, when a popular eugenics movement emerged in the United Kingdom, and then spread to many countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, and most European countries (e.g. Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

). In this period, people from across the political spectrum espoused eugenics. Many countries adopted eugenic policies intended to improve the quality of their populations.

Historically, the idea of ''eugenics'' has been used to argue for a broad array of practices ranging from prenatal care

Prenatal care, also known as antenatal care, is a type of preventive healthcare for pregnant individuals. It is provided in the form of medical checkups and healthy lifestyle recommendations for the pregnant person. Antenatal care also consists of ...

for mothers deemed genetically desirable to the forced sterilization and murder of those deemed unfit. To population geneticists, the term has included the avoidance of inbreeding

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely genetic distance, related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genet ...

without altering allele frequencies; for example, British-Indian scientist J. B. S. Haldane wrote in 1940 that "the motor bus, by breaking up inbred village communities, was a powerful eugenic agent." Debate as to what qualifies as eugenics continues today. Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with factors of measured intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

that often correlated strongly with social class and racial stereotypes.

Although it originated as a progressive social movement in the 19th century, in the 21st century the term became closely associated with scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

. New liberal eugenics seeks to dissociate itself from the old authoritarian varieties by rejecting coercive state programs in favor of individual parental choice.

Common distinctions

Eugenic programs included both ''positive'' measures, such as encouraging individuals deemed particularly "fit" to reproduce, and ''negative'' measures, such as marriage prohibitions andforced sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, refers to any government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually do ...

of people deemed unfit for reproduction.

Positive eugenics is aimed at encouraging reproduction among the genetically advantaged, for example, the intelligent, the healthy, and the successful. Possible approaches include financial and political stimuli, targeted demographic analyses, ''in vitro'' fertilization, egg transplants, and cloning. Negative eugenics aimed to eliminate, through sterilization or segregation, those deemed physically, mentally, or morally undesirable. This includes abortions, sterilization, and other methods of family planning. Both positive and negative eugenics can be coercive; in Nazi Germany, for example, abortion was illegal for women deemed by the state to be superior.

As opposed to "euthenics"

Historical eugenics

Ancient and medieval origins

According toPlutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, in Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

every proper citizen's child was inspected by the council of elders, the Gerousia

The Gerousia (γερουσία) was the council of elders in ancient Sparta. Sometimes called Spartan senate in the literature, it was made up of the two Spartan kings, plus 28 Spartiates over the age of sixty, known as gerontes. The Gerousia ...

, which determined whether or not the child was fit to live. If the child was deemed unfit, the child was thrown into a chasm. Plutarch is the sole historical source for the Spartan practice of systemic infanticide motivated by eugenics. While infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of re ...

was practiced by Greeks, no contemporary sources support Plutarch's claims of mass infanticide motivated by eugenics. In 2007 the suggestion that infants were dumped near Mount Taygete was called into question due to a lack of physical evidence. Anthropologist Theodoros Pitsios' research found only bodies from adolescents up to the age of approximately 35.

Plato's political philosophy included the belief that human reproduction should be cautiously monitored and controlled by the state through selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...

.

According to Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical works, ''Annals'' ( ...

( – ), a Roman of the Imperial Period, the Germanic tribes of his day killed any member of their community they deemed cowardly, unwarlike or "stained with abominable vices", usually by drowning them in swamps. Modern historians see Tacitus' ethnographic writing as unreliable in such details.

Academic origins

The term ''eugenics'' and its modern field of study were first formulated by

The term ''eugenics'' and its modern field of study were first formulated by Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics.

Galton produced over 340 papers and b ...

in 1883, directly drawing on the recent work delineating natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

by his half-cousin Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

. He published his observations and conclusions chiefly in his influential book '' Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development''. Galton himself defined it as "the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations". The first to systematically apply Darwinism theory to human relations, Galton believed that various desirable human qualities were also hereditary ones, although Darwin strongly disagreed with this elaboration of his theory.

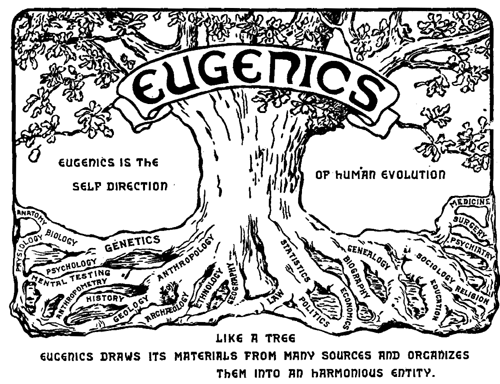

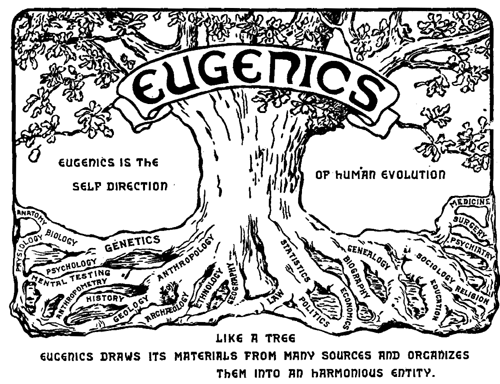

Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities and received funding from various sources. Organizations were formed to win public support for and to sway opinion towards responsible eugenic values in parenthood, including the British Eugenics Education Society of 1907 and the American Eugenics Society

The American Eugenics Society (AES) was a pro-eugenics organization dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of huma ...

of 1921. Both sought support from leading clergymen and modified their message to meet religious ideals. In 1909, the Anglican clergymen William Inge and James Peile both wrote for the Eugenics Education Society. Inge was an invited speaker at the 1921 International Eugenics Conference, which was also endorsed by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York Patrick Joseph Hayes.

Three International Eugenics Conferences presented a global venue for eugenicists, with meetings in 1912 in London, and in 1921 and 1932 in New York City. Eugenic policies in the United States were first implemented by state-level legislators in the early 1900s. Eugenic policies also took root in France, Germany, and Great Britain. Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, the eugenic policy of sterilizing certain mental patients was implemented in other countries including Belgium, Brazil, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

.

Frederick Osborn's 1937 journal article "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy" framed eugenics as a social philosophy

Social philosophy is the study and interpretation of society and social institutions in terms of ethical values rather than empirical relations. Social philosophers emphasize understanding the social contexts for political, legal, moral and cultur ...

—a philosophy with implications for social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social orde ...

. That definition is not universally accepted. Osborn advocated for higher rates of sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

among people with desired traits ("positive eugenics") or reduced rates of sexual reproduction or sterilization of people with less-desired or undesired traits ("negative eugenics").

In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations. Its scientific aspects were carried on through research bodies such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, the Cold Spring Harbor Carnegie Institution for Experimental Evolution, and the Eugenics Record Office. Politically, the movement advocated measures such as sterilization laws. In its moral dimension, eugenics rejected the doctrine that all human beings are born equal and redefined moral worth purely in terms of genetic fitness. Its racist elements included pursuit of a pure "Nordic race

The Nordic race is an obsolete racial classification of humans based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. It was once considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists di ...

" or "Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

" genetic pool and the eventual elimination of "unfit" races.

Many leading British politicians subscribed to the theories of eugenics. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

supported the British Eugenics Society and was an honorary vice president for the organization. Churchill believed that eugenics could solve "race deterioration" and reduce crime and poverty.

As a social movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century, when it was practiced around the world and promoted by governments, institutions, and influential individuals. Many countries enacted various eugenics policies, including: genetic screenings, birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

and sequestering the mentally ill), compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, refers to any government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually do ...

, forced abortion

Forced abortion is a form of reproductive coercion that refers to the act of compelling a woman to undergo termination of a pregnancy against her will or without explicit consent. Forced abortion may also be defined as coerced abortion, and may o ...

s or forced pregnancies, ultimately culminating in genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

. By 2014, gene selection (rather than "people selection") was made possible through advances in genome editing

Genome editing, or genome engineering, or gene editing, is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted, modified or replaced in the genome of a living organism. Unlike early genetic engineering techniques that randomly insert ge ...

, leading to what is sometimes called '' new eugenics'', also known as "neo-eugenics", "consumer eugenics", or "liberal eugenics"; which focuses on individual freedom and allegedly pulls away from racism, sexism or a focus on intelligence.

Early opposition

Early critics of the philosophy of eugenics included the American sociologist Lester Frank Ward, the English writer G. K. Chesterton, and Scottish tuberculosis pioneer and author Halliday Sutherland. Ward's 1913 article "Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics", Chesterton's 1917 book ''Eugenics and Other Evils'', andFranz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

' 1916 article "Eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

" (published in ''The Scientific Monthly

''The Scientific Monthly'' was a science magazine published from 1915 to 1957. Psychologist James McKeen Cattell, the former publisher and editor of '' The Popular Science Monthly'', was the original founder and editor. In 1958, ''The Scientific M ...

'') were all harshly critical of the rapidly growing movement.

Several biologists were also antagonistic to the eugenics movement, including Lancelot Hogben

Lancelot Thomas Hogben FRS FRSE (9 December 1895 – 22 August 1975) was a British experimental zoologist and medical statistician. He developed the African clawed frog ''(Xenopus laevis)'' as a model organism for biological research in his e ...

. Other biologists who were themselves eugenicists, such as J. B. S. Haldane and R. A. Fisher, however, also expressed skepticism in the belief that sterilization of "defectives" (i.e. a purely negative eugenics) would lead to the disappearance of undesirable genetic traits.

Among institutions, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

opposes sterilization for eugenic purposes. Attempts by the Eugenics Education Society to persuade the British government to legalize voluntary sterilization were opposed by Catholics and by the Labour Party. The American Eugenics Society

The American Eugenics Society (AES) was a pro-eugenics organization dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of huma ...

initially gained some Catholic supporters, but Catholic support declined following the 1930 papal encyclical '' Casti connubii''. In this, Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

explicitly condemned sterilization laws: "Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason."

The eugenicists' political successes in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

were not at all matched in such countries as Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, even though measures had been proposed there, largely because of the Catholic church's moderating influence.

Eugenic feminism

North American eugenics

Eugenics in Mexico

Nazism and the decline of eugenics

The reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany.

The reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in in 1925 and emulated eugenic legislation for the sterilization of "defectives" that had been pioneered in the United States once he took power. Some common early 20th century eugenics methods involved identifying and classifying individuals and their families. This included racial groups (such as the Roma and Jews in Nazi Germany), the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women, and homosexuals as "degenerate" or "unfit". This led to segregation, institutionalization, sterilization, and mass murder

Mass murder is the violent crime of murder, killing a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. A mass murder typically occurs in a single location where one or more ...

. The Nazi policy of identifying German citizens deemed unfit and then systematically killing them with poison gas, referred to as the Aktion T4

(German, ) was a campaign of Homicide#By state actors, mass murder by involuntary euthanasia which targeted Disability, people with disabilities and the mentally ill in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-WWII, war trials against d ...

campaign, paved the way for the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

.

By the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, many eugenics laws were abandoned, having become associated with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

, who had called for "the sterilization of failures" in 1904, stated in his 1940 book ''The Rights of Man: Or What Are We Fighting For?'' that among the human rights, which he believed should be available to all people, was "a prohibition on mutilation

Mutilation or maiming (from the ) is Bodily harm, severe damage to the body that has a subsequent harmful effect on an individual's quality of life.

In the modern era, the term has an overwhelmingly negative connotation, referring to alteratio ...

, sterilization, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

, and any bodily punishment". After World War II, the practice of "imposing measures intended to prevent births within national, ethnical, racial or religiousgroup" fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an International Agreement, international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of ...

. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR) enshrines certain political, social, and economic rights for European Union (EU) citizens and residents into EU law. It was drafted by the European Convention and solemnly procla ...

also proclaims "the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at selection of persons".

In Singapore

Lee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew (born Harry Lee Kuan Yew; 16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015), often referred to by his initials LKY, was a Singaporean politician who ruled as the first Prime Minister of Singapore from 1959 to 1990. He is widely recognised ...

, the founding father of Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, actively promoted eugenics as late as 1983. In 1984, Singapore began providing financial incentives to highly educated women to encourage them to have more children. For this purpose was introduced the "Graduate Mother Scheme" that incentivized graduate women to get married as much as the rest of their populace. The incentives were extremely unpopular and regarded as eugenic, and were seen as discriminatory towards Singapore's non-Chinese ethnic population. In 1985, the incentives were partly abandoned as ineffective, while the government matchmaking agency, the Social Development Network, remains active.

Modern eugenics

Liberal eugenics, also called new eugenics, aims to make genetic interventions morally acceptable by rejecting coercive state programs and relying on parental choice. Bioethicist Nicholas Agar, who coined the term, argues that the state should intervene only to forbid interventions that excessively limit a child’s ability to shape their own future. Unlike "authoritarian" or "old" eugenics, liberal eugenics draws on modern scientific knowledge ofgenomics

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, ...

to enable informed choices aimed at improving well-being. Julien Savulescu further argues that some eugenic practices, like prenatal screening for Down syndrome, are already widely practiced, without being labeled "eugenics", as they are seen as enhancing freedom rather than restricting it.

UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after the Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkele ...

sociologist Troy Duster

Troy Smith Duster (born July 11, 1936) is an American sociologist with research interests in the sociology of science, public policy, race and ethnicity and deviance. He is a Chancellor's Professor of Sociology at University of California, Berkele ...

argued that modern genetics is a "back door to eugenics". This view was shared by then-White House Assistant Director for Forensic Sciences, Tania Simoncelli, who stated in a 2003 publication by the Population and Development Program at Hampshire College

Hampshire College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. It was opened in 1970 as an experiment in alternative education, in association with four other colleges ...

that advances in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) are moving society to a "new era of eugenics", and that, unlike the Nazi eugenics, modern eugenics is consumer driven and market based, "where children are increasingly regarded as made-to-order consumer products". The United Nations' International Bioethics Committee also noted that while human genetic engineering should not be confused with the 20th century eugenics movements, it nonetheless challenges the idea of human equality and opens up new forms of discrimination and stigmatization for those who do not want or cannot afford the technology.

In 2025, geneticist Peter Visscher published a paper in ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

,'' arguing genome editing of human embryos and germ cells may become feasible in the 21st century, and raising ethical considerations in the context of previous eugenics movements. A response argued that human embryo genetic editing is "unsafe and unproven". ''Nature'' also published an editorial, stating: "The fear that polygenic gene editing could be used for eugenics looms large among them, and is, in part, why no country currently allows genome editing in a human embryo, even for single variants".

Contested scientific status

One general concern that the reduced

One general concern that the reduced genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

may be a feature of long-term, species-wide eugenics plans, could eventually result in inbreeding depression

Inbreeding depression is the reduced biological fitness caused by loss of genetic diversity as a consequence of inbreeding, the breeding of individuals closely related genetically. This loss of genetic diversity results from small population siz ...

, increased spread of infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

, and decreased resilience to changes in the environment.

Arguments for scientific validity

In his original lecture "Darwinism, Medical Progress and Eugenics",Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson (; born Carl Pearson; 27 March 1857 – 27 April 1936) was an English biostatistician and mathematician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university ...

claimed that everything concerning eugenics fell into the field of medicine. Anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička

Alois Ferdinand Hrdlička, after 1918 changed to Aleš Hrdlička (; March 30,HRDLICKA, ALES ...

said in 1918 that " e growing science of eugenics will essentially become applied anthropology." The economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

was a lifelong proponent of eugenics and described it as a branch of sociology.

In a 2006 newspaper article, Richard Dawkins said that discussion regarding eugenics was inhibited by the shadow of Nazi misuse, to the extent that some scientists would not admit that breeding humans for certain abilities is at all possible. He believes that it is not physically different from breeding domestic animals for traits such as speed or herding skill. Dawkins felt that enough time had elapsed to at least ask just what the ethical differences were between breeding for ability versus training athletes or forcing children to take music lessons, though he could think of persuasive reasons to draw the distinction.

Objections to scientific validity

Amanda Caleb, Professor of Medical Humanities at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, says "Eugenic laws and policies are now understood as part of a specious devotion to a pseudoscience that actively dehumanizes to support political agendas and not true science or medicine." The first major challenge to conventional eugenics based on genetic inheritance was made in 1915 byThomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an Americans, American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, Embryology, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries e ...

. He demonstrated the event of genetic mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitosis ...

occurring outside of inheritance involving the discovery of the hatching of a fruit fly (''Drosophila melanogaster'') with white eyes from a family with red eyes, demonstrating that major genetic changes occurred outside of inheritance. Morgan criticized the view that traits such as intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

or criminality were hereditary, because these traits were subjective.

Pleiotropy

Pleiotropy () is a condition in which a single gene or genetic variant influences multiple phenotypic traits. A gene that has such multiple effects is referred to as a ''pleiotropic gene''. Mutations in pleiotropic genes can impact several trait ...

occurs when one gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

influences multiple, seemingly unrelated phenotypic trait

A phenotypic trait, simply trait, or character state is a distinct variant of a phenotypic characteristic of an organism; it may be either inherited or determined environmentally, but typically occurs as a combination of the two.Lawrence, Eleano ...

s, an example being phenylketonuria

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is an inborn error of metabolism that results in decreased metabolism of the amino acid phenylalanine. Untreated PKU can lead to intellectual disability, seizures, behavioral problems, and mental disorders. It may also r ...

, which is a human disease that affects multiple systems but is caused by one gene defect. Andrzej Pękalski, from the University of Wroclaw, argues that eugenics can cause harmful loss of genetic diversity if a eugenics program selects a pleiotropic gene that could possibly be associated with a positive trait. Pękalski uses the example of a coercive government eugenics program that prohibits people with myopia

Myopia, also known as near-sightedness and short-sightedness, is an eye condition where light from distant objects focuses in front of, instead of on, the retina. As a result, distant objects appear blurry, while close objects appear normal. ...

from breeding but has the unintended consequence of also selecting against high intelligence since the two were associated.

While the science of genetics has increasingly provided means by which certain characteristics and conditions can be identified and understood, given the complexity of human genetics, culture, and psychology, at this point there is no agreed objective means of determining which traits might be ultimately desirable or undesirable. Some conditions such as sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD), also simply called sickle cell, is a group of inherited haemoglobin-related blood disorders. The most common type is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying ...

and cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

respectively confer immunity to malaria and resistance to cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

when a single copy of the recessive allele is contained within the genotype of the individual, so eliminating these genes is undesirable in places where such diseases are common.

Edwin Black

Edwin Black (born February 27, 1950) is an American historian and author, as well as a print syndication, syndicated columnist, investigative journalist, and weekly talk show host on The Edwin Black Show. He specializes in human rights, the hist ...

, journalist, historian, and author of ''War Against the Weak'', argues that eugenics is often deemed a pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

because what is defined as a genetic improvement of a desired trait is a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined through objective scientific inquiry. This aspect of eugenics is often considered to be tainted with scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

and pseudoscience.

Contested ethical status

Contemporary ethical opposition

In a book directly addressed at socialist eugenicist J.B.S. Haldane and his once-influential ''Daedalus

In Greek mythology, Daedalus (, ; Greek language, Greek: Δαίδαλος; Latin language, Latin: ''Daedalus''; Etruscan language, Etruscan: ''Taitale'') was a skillful architect and craftsman, seen as a symbol of wisdom, knowledge and power. H ...

'', Betrand Russell had one serious objection of his own: eugenic policies might simply end up being used to reproduce existing power relations "rather than to make men happy."

Environmental ethicist Bill McKibben

William Ernest McKibben (born December 8, 1960)"Bill Ernest McKibben." ''Environmental Encyclopedia''. Edited by Deirdre S. Blanchfield. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 2009. Retrieved via ''Biography in Context'' database, December 31, 2017. is a ...

argued against germinal choice technology and other advanced biotechnological strategies for human enhancement. He writes that it would be morally wrong for humans to tamper with fundamental aspects of themselves (or their children) in an attempt to overcome universal human limitations, such as vulnerability to aging

Ageing (or aging in American English) is the process of becoming Old age, older until death. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi; whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentiall ...

, maximum life span and biological constraints on physical and cognitive ability. Attempts to "improve" themselves through such manipulation would remove limitations that provide a necessary context for the experience of meaningful human choice. He claims that human lives would no longer seem meaningful in a world where such limitations could be overcome with technology. Even the goal of using germinal choice technology for clearly therapeutic purposes should be relinquished, he argues, since it would inevitably produce temptations to tamper with such things as cognitive capacities. He argues that it is possible for societies to benefit from renouncing particular technologies, using Ming China

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

, Tokugawa Japan and the contemporary Amish

The Amish (, also or ; ; ), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, church fellowships with Swiss people, Swiss and Alsace, Alsatian origins. As they ...

as examples.

Contemporary ethical advocacy

Bioethicist

Bioethics is both a field of study and professional practice, interested in ethics, ethical issues related to health (primarily focused on the human, but also increasingly includes animal ethics), including those emerging from advances in biolo ...

Stephen Wilkinson has said that some aspects of modern genetics can be classified as eugenics, but that this classification does not inherently make modern genetics immoral.

Historian Nathaniel C. Comfort has claimed that the change from state-led reproductive-genetic decision-making to individual choice has moderated the worst abuses of eugenics by transferring the decision-making process from the state to patients and their families.

In their book published in 2000, ''From Chance to Choice: Genetics and Justice'', bioethicists Allen Buchanan

Allen Edward Buchanan (born 1948) is a moral, political and legal philosopher. As of 2022, he held multiple academic positions: Laureate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Arizona, Distinguished Research Fellow at Oxford University, Vi ...

, Dan Brock, Norman Daniels and Daniel Wikler argued that liberal societies have an obligation to encourage as wide an adoption of eugenic enhancement technologies as possible (so long as such policies do not infringe on individuals' reproductive rights

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to human reproduction, reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights:

Reproductive rights ...

or exert undue pressures on prospective parents to use these technologies) in order to maximize public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the de ...

and minimize the inequalities that may result from both natural genetic endowments and unequal access to genetic enhancements.

In science fiction

Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931, and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hier ...

'' by the English author Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley ( ; 26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. His bibliography spans nearly 50 books, including non-fiction novel, non-fiction works, as well as essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the ...

(1931), is a dystopian

A dystopia (lit. "bad place") is an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives. It is an imagined place (possibly state) in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmenta ...

social science fiction novel which is set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarchy

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). ...

.

Various works by the author Robert A. Heinlein mention the Howard Foundation, a group which attempts to improve human longevity through selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...

.

Among Frank Herbert

Franklin Patrick Herbert Jr. (October 8, 1920February 11, 1986) was an American science-fiction author, best known for his 1965 novel Dune (novel), ''Dune'' and its five sequels. He also wrote short stories and worked as a newspaper journalist, ...

's other works, the ''Dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, flat ...

'' series, starting with the eponymous 1965 novel, describes selective breeding by a powerful sisterhood, the '' Bene Gesserit'', to produce a supernormal male being, the ''Kwisatz Haderach''.

The Star Trek

''Star Trek'' is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the Star Trek: The Original Series, series of the same name and became a worldwide Popular culture, pop-culture Cultural influence of ...

franchise features a race of genetically engineered humans which is known as "Augments", the most notable of them being Khan Noonien Singh. These "supermen" were the cause of the Eugenics Wars, a dark period in Earth's fictional history, before they were deposed and exiled. Spin-offs like '' Star Trek: Deep Space Nine'' and '' Star Trek: Strange New Worlds'' present the Eugenics Wars as the main reason why genetic enhancement is illegal in the United Federation of Planets

In the fictional universe of ''Star Trek'', the United Federation of Planets (UFP) is the interstellar government with which, as part of its space force Starfleet, most of the characters and starships of the franchise are affiliated. Commonly re ...

.

Gattaca

''Gattaca'' is a 1997 American dystopian science fiction film written and directed by Andrew Niccol in his List of directorial debuts, feature directorial debut. It stars Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman with Jude Law, Loren Dean, Ernest Borgnine, Go ...

'' (1997) provides a fictional example of a dystopian

A dystopia (lit. "bad place") is an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives. It is an imagined place (possibly state) in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmenta ...

society that uses eugenics to decide what people are capable of and their place in the world. The title alludes to the letters G, A, T and C, the four nucleobase

Nucleotide bases (also nucleobases, nitrogenous bases) are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nuc ...

s of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

, and depicts the possible consequences of genetic discrimination

Genetic discrimination occurs when people treat others (or are treated) differently because they have or are perceived to have a gene mutation(s) that causes or increases the risk of an inherited disorder. It may also refer to any and all discr ...

in the present societal framework. Relegated to the role of a cleaner owing to his genetically projected death at age 32 due to a heart condition (being told: "The only way you'll see the inside of a spaceship is if you were cleaning it"), the protagonist observes enhanced astronauts as they are demonstrating their superhuman athleticism. Although it was not a box office success, it was critically acclaimed and influenced the debate over human genetic engineering in the public consciousness. As to its accuracy, its production company, Sony Pictures

Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. is an American diversified multinational mass media and entertainment studio conglomerate that produces, acquires, and distributes filmed entertainment (theatrical motion pictures, television programs, and rec ...

, consulted with a gene therapy

Gene therapy is Health technology, medical technology that aims to produce a therapeutic effect through the manipulation of gene expression or through altering the biological properties of living cells.

The first attempt at modifying human DNA ...

researcher and prominent critic of eugenics known to have stated that " should not step over the line that delineates treatment from enhancement", W. French Anderson, to ensure that the portrayal of science was realistic. Disputing their success in this mission, Philim Yam of ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it, with more than 150 Nobel Pri ...

'' called the film "science bashing" and ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

's'' Kevin Davies called it a "surprisingly pedestrian affair", while molecular biologist

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

Lee Silver described its extreme determinism

Determinism is the Metaphysics, metaphysical view that all events within the universe (or multiverse) can occur only in one possible way. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes ov ...

as "a straw man".

In his 2018 book ''Blueprint

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842. The process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number ...

'', the behavioral geneticist Robert Plomin writes that while ''Gattaca'' warned of the dangers of genetic information being used by a totalitarian state, genetic testing could also favor better meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods or political power are vested in individual people based on ability and talent, rather than ...

in democratic societies which already administer a variety of standardized test

A standardized test is a Test (assessment), test that is administered and scored in a consistent or standard manner. Standardized tests are designed in such a way that the questions and interpretations are consistent and are administered and scored ...

s to select people for education and employment. He suggests that polygenic scores might supplement testing in a manner that is essentially free of biases.

See also

*Ableism

Ableism (; also known as ablism, disablism (British English), anapirophobia, anapirism, and disability discrimination) is discrimination and social prejudice against physically or mentally disabled people. Ableism characterizes people as they a ...

* Bioconservatism

* Culling

Culling is the process of segregating organisms from a group according to desired or undesired characteristics. In animal breeding, it is removing or segregating animals from a breeding stock based on a specific trait. This is done to exagge ...

* Dor Yeshorim

* Dysgenics

* Eugenic feminism

* Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of Genetic engineering techniques, technologies used to change the genet ...

* Genetic enhancement

* Hereditarianism

* Heritability of IQ

Research on the heritability of intelligence quotient (IQ) inquires into the degree of variation in IQ within a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population. There has been significant controversy in the academ ...

* Mendelian traits in humans

** Simple Mendelian genetics in humans

* Moral enhancement

* ''Project Prevention

Project Prevention (formerly Children Requiring a Caring Kommunity or CRACK) is an American non-profit organization that pays drug addicts cash for volunteering for long-term birth control, including Human sterilization (surgical procedure), ster ...

''

* Social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

* Transhumanism

Transhumanism is a philosophical and intellectual movement that advocates the human enhancement, enhancement of the human condition by developing and making widely available new and future technologies that can greatly enhance longevity, cogni ...

* Wrongful life

* Eugenics in France

References

Notes

External links

H-Eugenics, H-Net's network on the history of eugenics

from

Michigan State University

Michigan State University (Michigan State or MSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in East Lansing, Michigan, United States. It was founded in 1855 as the Agricultural College of the State o ...

Eugenics: Its Origin and Development (1883–Present)

by the

National Human Genome Research Institute

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) is an institute of the National Institutes of Health, located in Bethesda, Maryland.

NHGRI began as the Office of Human Genome Research in The Office of the Director in 1988. This Office transi ...

(30 November 2021)

Eugenics and Scientific Racism Fact Sheet

by the

National Human Genome Research Institute

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) is an institute of the National Institutes of Health, located in Bethesda, Maryland.

NHGRI began as the Office of Human Genome Research in The Office of the Director in 1988. This Office transi ...

(3 November 2021)

{{Authority control

Ableism

Applied genetics

Bioethics

Nazism

Pseudo-scholarship

Pseudoscience

Racism

Technological utopianism

White supremacy