Edwin Armstrong on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edwin Howard Armstrong (December 18, 1890 – February 1, 1954) was an American

Armstrong was born in the Chelsea district of New York City, the oldest of John and Emily (née Smith) Armstrong's three children. His father began working at a young age at the American branch of the

Armstrong was born in the Chelsea district of New York City, the oldest of John and Emily (née Smith) Armstrong's three children. His father began working at a young age at the American branch of the

p. 27

/ref> He loved heights and constructed a makeshift backyard antenna tower that included a

Armstrong began working on his first major invention while still an undergraduate at Columbia. In late 1906,

Armstrong began working on his first major invention while still an undergraduate at Columbia. In late 1906,

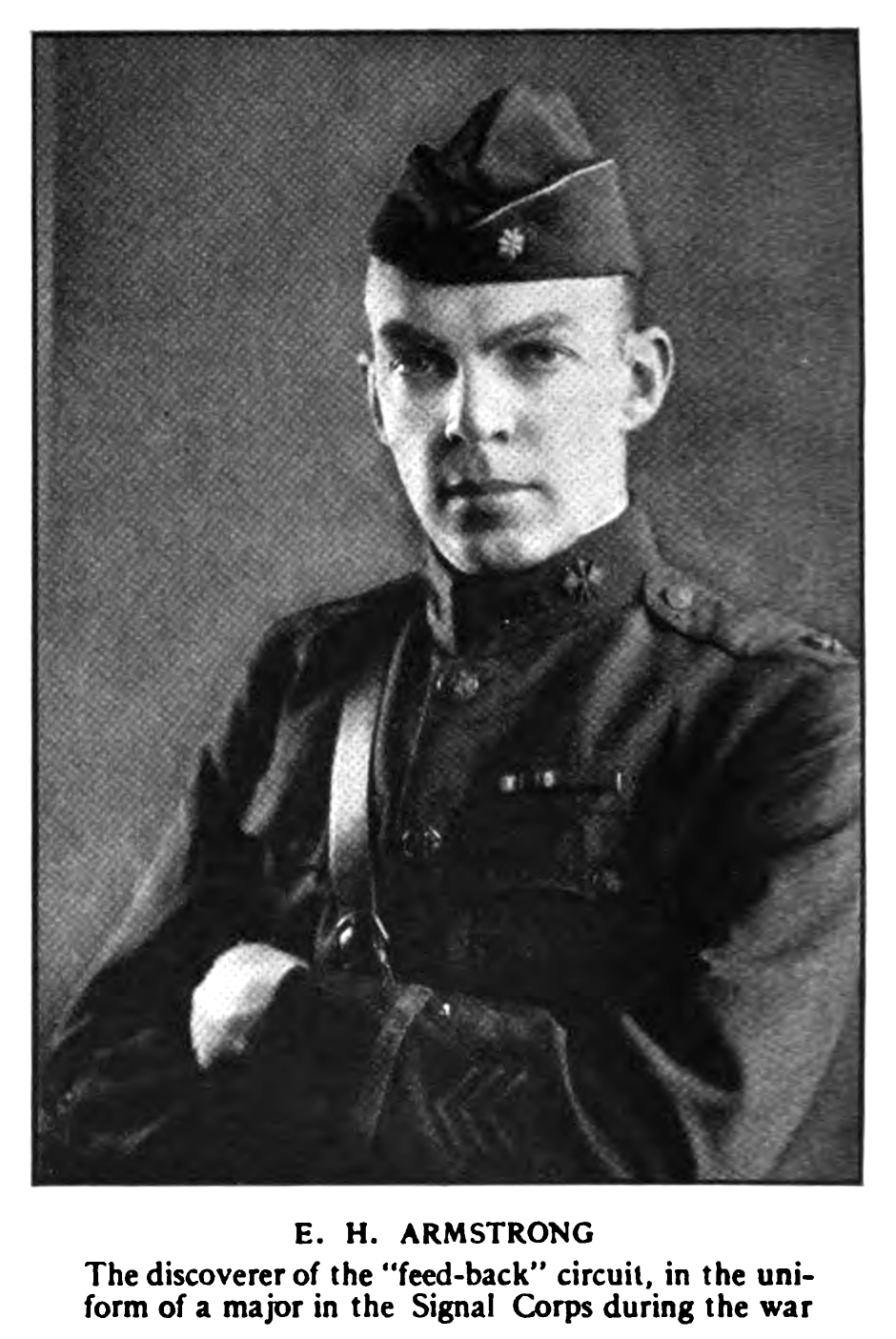

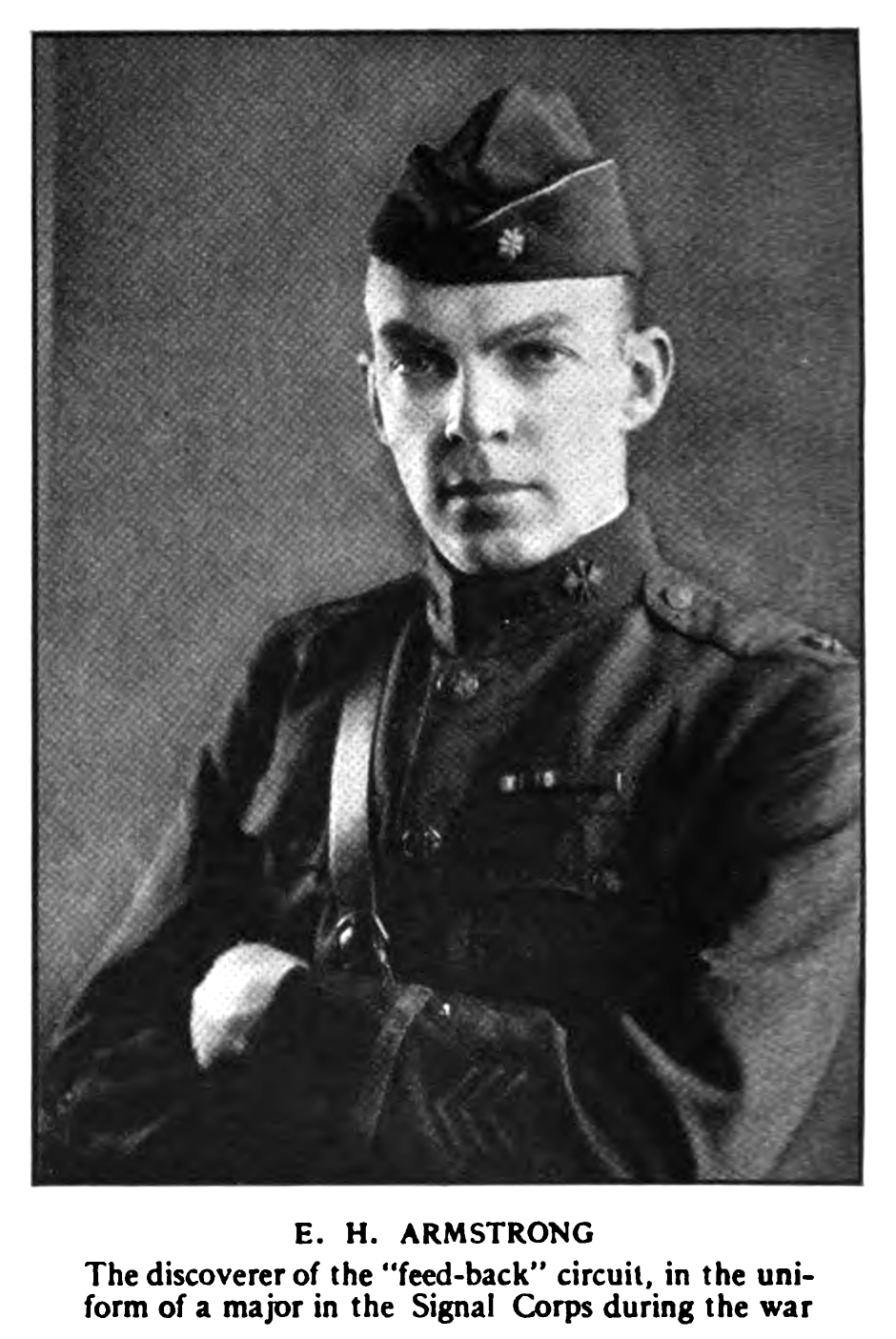

The United States entered WWI in April 1917. Later that year Armstrong was commissioned as a captain in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and assigned to a laboratory in Paris, France to help develop radio communication for the Allied war effort. He returned to the US in the autumn of 1919, after being promoted to the rank of Major. (During both world wars, Armstrong gave the US military free use of his patents.)

During this period, Armstrong's most significant accomplishment was the development of a "supersonic heterodyne" – soon shortened to "superheterodyne" – radio receiver circuit. This circuit made radio receivers more sensitive and selective and is used extensively today. The key feature of the superheterodyne approach is the mixing of the incoming radio signal with a locally generated, different frequency signal within a radio set. That circuit is called the mixer. The result is a fixed, unchanging intermediate frequency, or I.F. signal which is easily amplified and detected by following circuit stages. In 1919, Armstrong filed an application for a US patent of the superheterodyne circuit which was issued the next year. This patent was subsequently sold to Westinghouse. The patent was challenged, triggering another patent office interference hearing."Who Invented the Superheterodyne?"

The United States entered WWI in April 1917. Later that year Armstrong was commissioned as a captain in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and assigned to a laboratory in Paris, France to help develop radio communication for the Allied war effort. He returned to the US in the autumn of 1919, after being promoted to the rank of Major. (During both world wars, Armstrong gave the US military free use of his patents.)

During this period, Armstrong's most significant accomplishment was the development of a "supersonic heterodyne" – soon shortened to "superheterodyne" – radio receiver circuit. This circuit made radio receivers more sensitive and selective and is used extensively today. The key feature of the superheterodyne approach is the mixing of the incoming radio signal with a locally generated, different frequency signal within a radio set. That circuit is called the mixer. The result is a fixed, unchanging intermediate frequency, or I.F. signal which is easily amplified and detected by following circuit stages. In 1919, Armstrong filed an application for a US patent of the superheterodyne circuit which was issued the next year. This patent was subsequently sold to Westinghouse. The patent was challenged, triggering another patent office interference hearing."Who Invented the Superheterodyne?"

by Alan Douglas, originally published in ''The Legacies of Edwin Howard Armstrong'' from the "Proceedings of the Radio Club of America", Nov. 1990, Vol.64 no.3, pages 123-142. Page 139: "Lévy broadened his claims to purposely create an interference, by copying Armstrong's claims exactly. The Patent Office would then have to choose between the two inventors." Armstrong ultimately lost this patent battle; although the outcome was less controversial than that involving the regeneration proceedings. The challenger was Lucien Lévy of France who had worked developing Allied radio communication during WWI. He had been awarded French patents in 1917 and 1918 that covered some of the same basic ideas used in Armstrong's superheterodyne receiver. AT&T, interested in radio development at this time, primarily for point-to-point extensions of its wired telephone exchanges, purchased the US rights to Lévy's patent and contested Armstrong's grant. The subsequent court reviews continued until 1928, when the District of Columbia Court of Appeals disallowed all nine claims of Armstrong's patent, assigning priority for seven of the claims to Lévy, and one each to

In the late 1930s, as technical advances made it possible to transmit on higher frequencies, the FCC investigated options for increasing the number of broadcasting stations, in addition to ideas for better audio quality, known as "high-fidelity". In 1937 it introduced what became known as the Apex band, consisting of 75 broadcasting frequencies from 41.02 to 43.98 MHz. As on the standard broadcast band, these were AM stations but with higher quality audio – in one example, a frequency response from 20 Hz to 17,000 Hz +/- 1 dB – because station separations were 40 kHz instead of the 10 kHz spacings used on the original AM band. Armstrong worked to convince the FCC that a band of FM broadcasting stations would be a superior approach. That year he financed the construction of the first FM radio station, W2XMN (later

In the late 1930s, as technical advances made it possible to transmit on higher frequencies, the FCC investigated options for increasing the number of broadcasting stations, in addition to ideas for better audio quality, known as "high-fidelity". In 1937 it introduced what became known as the Apex band, consisting of 75 broadcasting frequencies from 41.02 to 43.98 MHz. As on the standard broadcast band, these were AM stations but with higher quality audio – in one example, a frequency response from 20 Hz to 17,000 Hz +/- 1 dB – because station separations were 40 kHz instead of the 10 kHz spacings used on the original AM band. Armstrong worked to convince the FCC that a band of FM broadcasting stations would be a superior approach. That year he financed the construction of the first FM radio station, W2XMN (later

In 1917, Armstrong was the first recipient of the IRE's (now IEEE)

In 1917, Armstrong was the first recipient of the IRE's (now IEEE)

Empire of the Air

. Documentary that first aired on PBS in 1992. *

Armstrong Memorial Research Foundation

– The Armstrong Foundation disseminates knowledge of Armstrong's research and achievements

Houck Collection

– A collection of images and documents that belonged to Armstrong's assistant, Harry W. Houck, which have been annotated by Mike Katzdorn.

Rare Book & Manuscript Library Collections

– A collection of images and documents at Columbia University

– A brief biography by Donna Halper * Ammon, Richard T., "

The Rolls Royce Of Reception

: Super Heterodynes – 1918 to 1930''". * IEEE History Center'

Edwin H. Armstrong

: Excerpt from "The Legacy of Edwin Howard Armstrong," by J. E. Brittain Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 79, no. 2, February 1991 * Hong, Sungook, "

A History of the Regeneration Circuit: From Invention to Patent Litigation

'" University, Seoul, Korea (PDF)

Who Invented the Superhetrodyne?

The history of the invention of the superhetrodyne receiver and related patent disputes * Yannis Tsividis,

, 2002. A profile on the web site of

electrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems that use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

and inventor who developed FM (frequency modulation

Frequency modulation (FM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, originally for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In frequency modulation a carrier wave is varied in its instantaneous frequency in proporti ...

) radio and the superheterodyne receiver system.

He held 42 patents and received numerous awards, including the first Medal of Honor awarded by the Institute of Radio Engineers (now IEEE

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) is an American 501(c)(3) organization, 501(c)(3) public charity professional organization for electrical engineering, electronics engineering, and other related disciplines.

The IEEE ...

), the French Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

, the 1941 Franklin Medal

The Franklin Medal was a science award presented from 1915 until 1997 by the Franklin Institute located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country ...

and the 1942 Edison Medal. He achieved the rank of major in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and was often referred to as "Major Armstrong" during his career. He was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a US patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also operate ...

and included in the International Telecommunication Union

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU)In the other common languages of the ITU:

*

* is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for many matters related to information ...

's roster of great inventors. He was inducted into the Wireless Hall of Fame posthumously in 2001. Armstrong attended Columbia University, and served as a professor there for most of his life.

Armstrong is also noted for his legal battles with Lee de Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

and David Sarnoff

David Sarnoff (February 27, 1891 – December 12, 1971) was a Russian and American businessman who played an important role in the American history of radio and television. He led the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) for most of his career in ...

, two other key figures in developing the early radio industry in the United States. The prolonged litigation took a toll on Armstrong's health and finances, which led to a breakdown in his marriage, followed by his suicide in 1954. Thereafter, his estate's legal cases were pursued by his widow, Marion, who won several successful suits and settlements.

Early life

Armstrong was born in the Chelsea district of New York City, the oldest of John and Emily (née Smith) Armstrong's three children. His father began working at a young age at the American branch of the

Armstrong was born in the Chelsea district of New York City, the oldest of John and Emily (née Smith) Armstrong's three children. His father began working at a young age at the American branch of the Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, which published bibles and standard classical works, eventually advancing to the position of vice president. His parents first met at the North Presbyterian Church, located at 31st Street and Ninth Avenue. His mother's family had strong ties to Chelsea, and an active role in church functions. When the church moved north, the Smiths and Armstrongs followed, and in 1895 the Armstrong family moved from their brownstone row house at 347 West 29th Street to a similar house at 26 West 97th Street on the Upper West Side

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper We ...

. The family was comfortably middle class.

At the age of eight, Armstrong contracted Sydenham's chorea

Sydenham's chorea, also known as rheumatic chorea, is a disorder characterized by Chorea, rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet. Sydenham's chorea is an autoimmune disease that results from childhood ...

(then known as St. Vitus' Dance), an infrequent but serious neurological disorder precipitated by rheumatic fever. For the rest of his life, Armstrong was afflicted with a physical tic

A tic is a sudden and repetitive motor movement or vocalization that is not rhythmic and involves discrete muscle groups. Tics are typically brief and may resemble a normal behavioral characteristic or gesture.

Tics can be invisible to the obs ...

exacerbated by excitement or stress. Due to this illness, he withdrew from public school and was home-tutored for two years. To improve his health, the Armstrong family moved to a house overlooking the Hudson River, at 1032 Warburton Avenue in Yonkers

Yonkers () is the List of municipalities in New York, third-most populous city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and the most-populous City (New York), city in Westchester County, New York, Westchester County. A centrally locate ...

. The Smith family subsequently moved next door. Armstrong's tic and the time missed from school led him to become socially withdrawn.

From an early age, Armstrong showed an interest in electrical and mechanical devices, particularly trains.Lessing 1956p. 27

/ref> He loved heights and constructed a makeshift backyard antenna tower that included a

bosun's chair

A bosun's chair (or boatswain's chair) is a device used to suspend a person from a rope to perform work aloft. Originally just a short plank or swath of heavy canvas, many modern bosun's chairs incorporate safety devices similar to those found ...

for hoisting himself up and down its length, to the concern of neighbors. Much of his early research was conducted in the attic of his parents' house.

In 1909, Armstrong enrolled at Columbia University in New York City, where he became a member of the Epsilon Chapter of the Theta Xi engineering fraternity, and studied under Professor Michael Pupin at the Hartley Laboratories, a separate research unit at Columbia. Another of his instructors, Professor John H. Morecroft, later remembered Armstrong as being intensely focused on the topics that interested him, but somewhat indifferent to the rest of his studies. Armstrong challenged conventional wisdom and was quick to question the opinions of both professors and peers. In one case, he recounted how he tricked a visiting professor from Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

that he disliked into receiving a severe electrical shock. He also stressed the practical over the theoretical, stating that progress was more likely the product of experimentation and reasoning than on mathematical calculation and the formulae of "mathematical physics

Mathematical physics is the development of mathematics, mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. The ''Journal of Mathematical Physics'' defines the field as "the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the de ...

".

Armstrong graduated from Columbia in 1913, earning an electrical engineering degree.

During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Armstrong served in the Signal Corps

A signal corps is a military branch, responsible for military communications (''signals''). Many countries maintain a signal corps, which is typically subordinate to a country's army.

Military communication usually consists of radio, telephone, ...

as a captain and later a major.

Following college graduation, he received a $600 one-year appointment as a laboratory assistant at Columbia, after which he nominally worked as a research assistant, for a salary of $1 a year, under Professor Pupin. Unlike most engineers, Armstrong never became a corporate employee. He set up a self-financed independent research and development laboratory at Columbia, and owned his patents outright.

In 1934, he filled the vacancy left by John H. Morecroft's death, receiving an appointment as a professor of Electrical Engineering at Columbia, a position he held the remainder of his life.

Early work

Regenerative circuit

Armstrong began working on his first major invention while still an undergraduate at Columbia. In late 1906,

Armstrong began working on his first major invention while still an undergraduate at Columbia. In late 1906, Lee de Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

had invented the three-element (triode) "grid Audion" vacuum-tube. How vacuum tubes worked was not understood at the time. De Forest's initial Audions did not have a high vacuum and developed a blue glow at modest plate voltages; De Forest improved the vacuum for Federal Telegraph. By 1912, vacuum tube operation was understood, and regenerative circuits using high-vacuum tubes were appreciated.

While growing up, Armstrong had experimented with the early temperamental, "gassy" Audions. Spurred by the later discoveries, he developed a keen interest in gaining a detailed scientific understanding of how vacuum tubes worked. In conjunction with Professor Morecroft he used an oscillograph to conduct comprehensive studies. His breakthrough discovery was determining that employing positive feedback

Positive feedback (exacerbating feedback, self-reinforcing feedback) is a process that occurs in a feedback loop where the outcome of a process reinforces the inciting process to build momentum. As such, these forces can exacerbate the effects ...

(also known as "regeneration") produced amplification hundreds of times greater than previously attained, with the amplified signals now strong enough so that receivers could use loudspeakers instead of headphones. Further investigation revealed that when the feedback was increased beyond a certain level a vacuum-tube would go into oscillation

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

, thus could also be used as a continuous-wave radio transmitter.

Beginning in 1913 Armstrong prepared a series of comprehensive demonstrations and papers that carefully documented his research, and in late 1913 applied for patent protection covering the regenerative circuit. On October 6, 1914, was issued for his discovery. Although Lee de Forest initially discounted Armstrong's findings, beginning in 1915 de Forest filed a series of competing patent applications that largely copied Armstrong's claims, now stating that he had discovered regeneration first, based on a notebook entry made on August 6, 1912, while working for the Federal Telegraph company, prior to the date recognized for Armstrong of January 31, 1913. The result was an interference hearing at the patent office to determine priority. De Forest was not the only other inventor involved – the four competing claimants included Armstrong, de Forest, General Electric's Langmuir, and Alexander Meissner, who was a German national, which led to his application being seized by the Office of Alien Property Custodian during World War I.

Following the end of WWI Armstrong enlisted representation by the law firm of Pennie, Davis, Martin and Edmonds. To finance his legal expenses he began issuing non-transferable licenses for use of the regenerative patents to a select group of small radio equipment firms, and by November 1920, 17 companies had been licensed. These licensees paid 5% royalties on their sales which were restricted to only "amateurs and experimenters". Meanwhile, Armstrong explored his options for selling the commercial rights to his work. Although the obvious candidate was the Radio Corporation of America

RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded in 1919 as the Radio Corporation of America. It was initially a patent pool, patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Westinghou ...

(RCA), on October 5, 1920, the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse and headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was ...

took out an option for $335,000 for the commercial rights for both the regenerative and superheterodyne patents, with an additional $200,000 to be paid if Armstrong prevailed in the regenerative patent dispute. Westinghouse exercised this option on November 4, 1920.

Legal proceedings related to the regeneration patent became separated into two groups of court cases. An initial court action was triggered in 1919 when Armstrong sued de Forest's company in district court, alleging infringement of patent 1,113,149. This court ruled in Armstrong's favor on May 17, 1921. A second line of court cases, the result of the patent office interference hearing, had a different outcome. The interference board had also sided with Armstrong, but he was unwilling to settle with de Forest for less than what he considered full compensation. Thus pressured, de Forest continued his legal defense, and appealed the interference board decision to the District of Columbia district court. On May 8, 1924, that court ruled that it was de Forest who should be considered regeneration's inventor. Armstrong (along with much of the engineering community) was shocked by these events, and his side appealed this decision. Although the legal proceeding twice went before the US Supreme Court, in 1928 and 1934, he was unsuccessful in overturning the decision.

In response to the second Supreme Court decision upholding de Forest as the inventor of regeneration, Armstrong attempted to return his 1917 IRE Medal of Honor, which had been awarded "in recognition of his work and publications dealing with the action of the oscillating and non-oscillating audion". The organization's board refused to allow him, and issued a statement that it "strongly affirms the original award".

Superheterodyne circuit

The United States entered WWI in April 1917. Later that year Armstrong was commissioned as a captain in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and assigned to a laboratory in Paris, France to help develop radio communication for the Allied war effort. He returned to the US in the autumn of 1919, after being promoted to the rank of Major. (During both world wars, Armstrong gave the US military free use of his patents.)

During this period, Armstrong's most significant accomplishment was the development of a "supersonic heterodyne" – soon shortened to "superheterodyne" – radio receiver circuit. This circuit made radio receivers more sensitive and selective and is used extensively today. The key feature of the superheterodyne approach is the mixing of the incoming radio signal with a locally generated, different frequency signal within a radio set. That circuit is called the mixer. The result is a fixed, unchanging intermediate frequency, or I.F. signal which is easily amplified and detected by following circuit stages. In 1919, Armstrong filed an application for a US patent of the superheterodyne circuit which was issued the next year. This patent was subsequently sold to Westinghouse. The patent was challenged, triggering another patent office interference hearing."Who Invented the Superheterodyne?"

The United States entered WWI in April 1917. Later that year Armstrong was commissioned as a captain in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and assigned to a laboratory in Paris, France to help develop radio communication for the Allied war effort. He returned to the US in the autumn of 1919, after being promoted to the rank of Major. (During both world wars, Armstrong gave the US military free use of his patents.)

During this period, Armstrong's most significant accomplishment was the development of a "supersonic heterodyne" – soon shortened to "superheterodyne" – radio receiver circuit. This circuit made radio receivers more sensitive and selective and is used extensively today. The key feature of the superheterodyne approach is the mixing of the incoming radio signal with a locally generated, different frequency signal within a radio set. That circuit is called the mixer. The result is a fixed, unchanging intermediate frequency, or I.F. signal which is easily amplified and detected by following circuit stages. In 1919, Armstrong filed an application for a US patent of the superheterodyne circuit which was issued the next year. This patent was subsequently sold to Westinghouse. The patent was challenged, triggering another patent office interference hearing."Who Invented the Superheterodyne?"by Alan Douglas, originally published in ''The Legacies of Edwin Howard Armstrong'' from the "Proceedings of the Radio Club of America", Nov. 1990, Vol.64 no.3, pages 123-142. Page 139: "Lévy broadened his claims to purposely create an interference, by copying Armstrong's claims exactly. The Patent Office would then have to choose between the two inventors." Armstrong ultimately lost this patent battle; although the outcome was less controversial than that involving the regeneration proceedings. The challenger was Lucien Lévy of France who had worked developing Allied radio communication during WWI. He had been awarded French patents in 1917 and 1918 that covered some of the same basic ideas used in Armstrong's superheterodyne receiver. AT&T, interested in radio development at this time, primarily for point-to-point extensions of its wired telephone exchanges, purchased the US rights to Lévy's patent and contested Armstrong's grant. The subsequent court reviews continued until 1928, when the District of Columbia Court of Appeals disallowed all nine claims of Armstrong's patent, assigning priority for seven of the claims to Lévy, and one each to

Ernst Alexanderson

Ernst Frederick Werner Alexanderson (; January 25, 1878 – May 14, 1975) was a Swedish-American electrical engineer and inventor who was a pioneer in radio development. He invented the Alexanderson alternator, an early radio transmitter used b ...

of General Electric and Burton W. Kendall of Bell Laboratories

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, the company operates several lab ...

.

Although most early radio receivers used regeneration Armstrong approached RCA's David Sarnoff

David Sarnoff (February 27, 1891 – December 12, 1971) was a Russian and American businessman who played an important role in the American history of radio and television. He led the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) for most of his career in ...

, whom he had known since giving a demonstration of his regeneration receiver in 1913, about the corporation offering superheterodynes as a superior offering to the general public. (The ongoing patent dispute was not a hindrance, because extensive cross-licensing agreements signed in 1920 and 1921 between RCA, Westinghouse and AT&T meant that Armstrong could freely use the Lévy patent.) Superheterodyne sets were initially thought to be prohibitively complicated and expensive as the initial designs required multiple tuning knobs and used nine vacuum tubes. In conjunction with RCA engineers, Armstrong developed a simpler, less costly design. RCA introduced its superheterodyne Radiola sets in the US market in early 1924, and they were an immediate success, dramatically increasing the corporation's profits. These sets were considered so valuable that RCA would not license the superheterodyne to other US companies until 1930.

Super-regeneration circuit

The regeneration legal battle had one serendipitous outcome for Armstrong. While he was preparing apparatus to counteract a claim made by a patent attorney, he "accidentally ran into the phenomenon of super-regeneration", where, by rapidly "quenching" the vacuum-tube oscillations, he was able to achieve even greater levels of amplification. A year later, in 1922, Armstrong sold his super-regeneration patent to RCA for $200,000 plus 60,000 shares of corporation stock, which was later increased to 80,000 shares in payment for consulting services. This made Armstrong RCA's largest shareholder, and he noted that "The sale of that invention was to net me more than the sale of the regenerative circuit and the superheterodyne combined". RCA envisioned selling a line of super-regenerative receivers until superheterodyne sets could be perfected for general sales, but it turned out the circuit was not selective enough to make it practical for broadcast receivers.Wide-band FM radio

"Static" interference – extraneous noises caused by sources such as thunderstorms and electrical equipment – bedeviled early radio communication usingamplitude modulation

Amplitude modulation (AM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, most commonly for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In amplitude modulation, the instantaneous amplitude of the wave is varied in proportion t ...

and perplexed numerous inventors attempting to eliminate it. Many ideas for static elimination were investigated, with little success. In the mid-1920s, Armstrong began researching a solution. He initially, and unsuccessfully, attempted to resolve the problem by modifying the characteristics of AM transmissions.

One approach used frequency modulation (FM) transmissions. Instead of varying the strength of the carrier wave as with AM, the frequency of the carrier was changed to represent the audio signal. In 1922 John Renshaw Carson of AT&T, inventor of Single-sideband modulation

In radio communications, single-sideband modulation (SSB) or single-sideband suppressed-carrier modulation (SSB-SC) is a type of signal modulation used to transmit information, such as an audio signal, by radio waves. A refinement of amplitu ...

(SSB), had published a detailed mathematical analysis which showed that FM transmissions did not provide any improvement over AM. Although the Carson bandwidth rule for FM is important today, Carson's review turned out to be incomplete, as it analyzed only (what is now known as) "narrow-band" FM.

In early 1928 Armstrong began researching the capabilities of FM. Although there were others involved in FM research at this time, he knew of an RCA project to see if FM shortwave transmissions were less susceptible to fading than AM. In 1931 the RCA engineers constructed a successful FM shortwave link transmitting the Schmeling– Stribling fight broadcast from California to Hawaii, and noted at the time that the signals seemed to be less affected by static. The project made little further progress.

Working in secret in the basement laboratory of Columbia's Philosophy Hall, Armstrong developed "wide-band" FM, in the process discovering significant advantages over the earlier "narrow-band" FM transmissions. In a "wide-band" FM system, the deviations of the carrier frequency are made to be much larger than the frequency of the audio signal which can be shown to provide better noise rejection. He was granted five US patents covering the basic features of the new system on December 26, 1933. Initially, the primary claim was that his FM system was effective at filtering out the noise produced in receivers, by vacuum tubes.

Armstrong had a standing agreement to give RCA the right of first refusal

Right of first refusal (ROFR or RFR) is a contractual right that gives its holder the option to enter a business transaction with the owner of something, according to specified terms, before the owner is entitled to enter into that transactio ...

to his patents. In 1934 he presented his new system to RCA president Sarnoff. Sarnoff was somewhat taken aback by its complexity, as he had hoped it would be possible to eliminate static merely by adding a simple device to existing receivers. From May 1934 until October 1935 Armstrong conducted field tests of his FM technology from an RCA laboratory located on the 85th floor of the Empire State Building

The Empire State Building is a 102-story, Art Deco-style supertall skyscraper in the Midtown South neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, United States. The building was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and built from 1930 to 1931. Its n ...

in New York City. An antenna attached to the building's spire transmitted signals for distances up to . These tests helped demonstrate FM's static-reduction and high-fidelity capabilities. RCA, which was heavily invested in perfecting TV broadcasting, chose not to invest in FM, and instructed Armstrong to remove his equipment.

Denied the marketing and financial clout of RCA, Armstrong decided to finance his own development and form ties with smaller members of the radio industry, including Zenith

The zenith (, ) is the imaginary point on the celestial sphere directly "above" a particular location. "Above" means in the vertical direction (Vertical and horizontal, plumb line) opposite to the gravity direction at that location (nadir). The z ...

and General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

, to promote his invention. Armstrong thought that FM had the potential to replace AM stations within 5 years, which he promoted as a boost for the radio manufacturing industry, then suffering from the effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. Making existing AM radio transmitters and receivers obsolete would necessitate that stations buy replacement transmitters and listeners purchase FM-capable receivers. In 1936 he published a landmark paper in the ''Proceedings of the IRE'' that documented the superior capabilities of using wide-band FM. (This paper would be reprinted in the August 1984 issue of ''Proceedings of the IEEE

The ''Proceedings of the IEEE'' is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). The journal focuses on electrical engineering and computer science. According to the ''Journa ...

''.) A year later, a paper by Murray G. Crosby (inventor of Crosby system for FM Stereo) in the same journal provided further analysis of the wide-band FM characteristics, and introduced the concept of "threshold", demonstrating that there is a superior signal-to-noise ratio

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR or S/N) is a measure used in science and engineering that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. SNR is defined as the ratio of signal power to noise power, often expressed in deci ...

when the signal is stronger than a certain level.

In June 1936, Armstrong gave a formal presentation of his new system at the US Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, internet, wi-fi, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains j ...

(FCC) headquarters. For comparison, he played a jazz record using a conventional AM radio, then switched to an FM transmission. A United Press

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20th ...

correspondent was present, and recounted in a wire service report that: "if the audience of 500 engineers had shut their eyes they would have believed the jazz band was in the same room. There were no extraneous sounds." Moreover, "Several engineers said after the demonstration that they consider Dr. Armstrong's invention one of the most important radio developments since the first earphone crystal sets were introduced." Armstrong was quoted as saying he could "visualize a time not far distant when the use of ultra-high frequency wave bands will play the leading role in all broadcasting", although the article noted that "A switchover to the ultra-high frequency system would mean the junking of present broadcasting equipment and present receivers in homes, eventually causing the expenditure of billions of dollars."

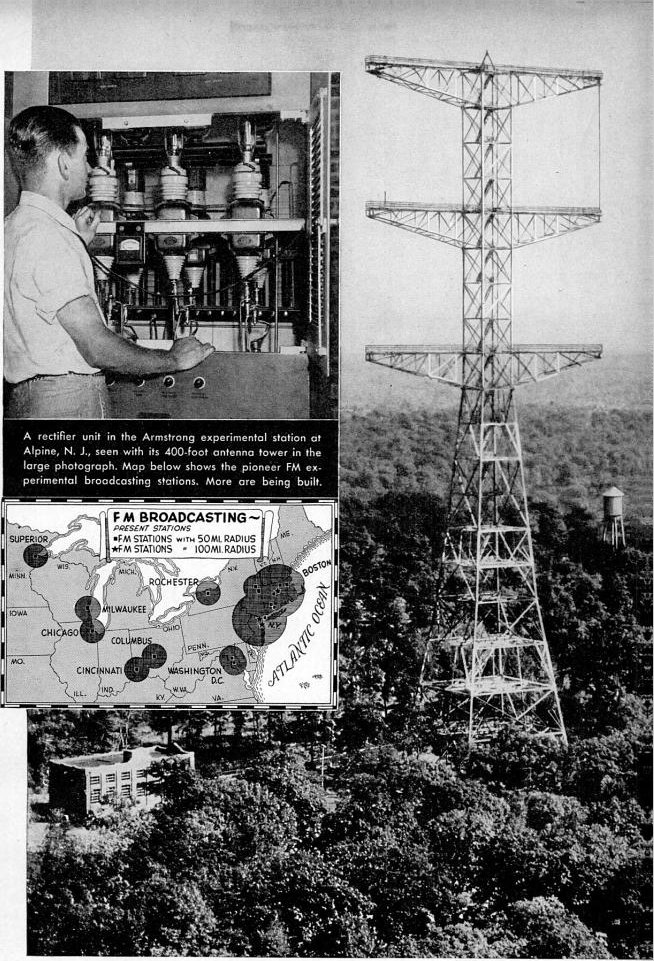

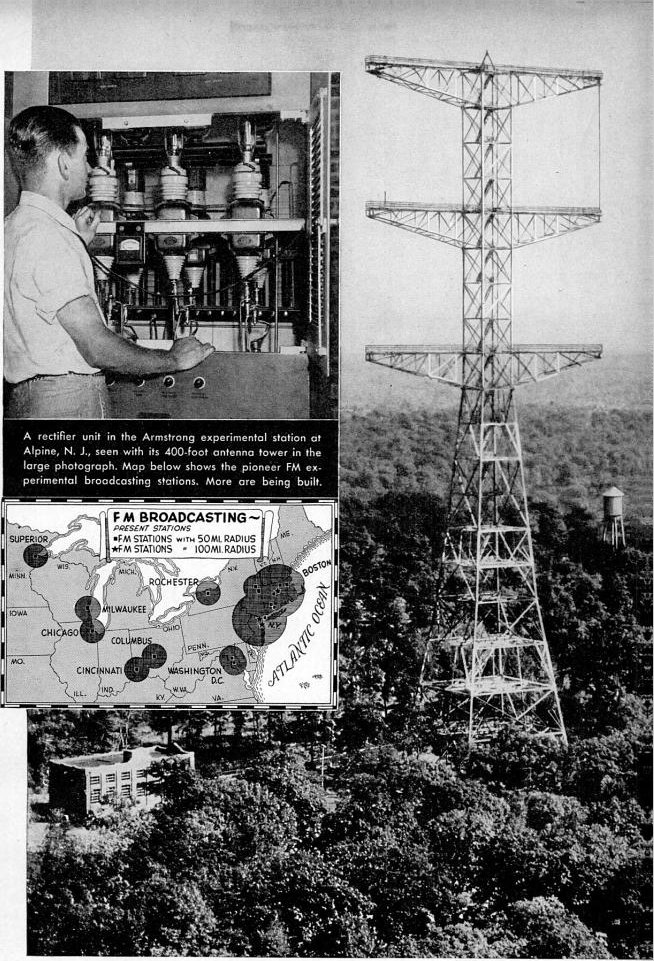

In the late 1930s, as technical advances made it possible to transmit on higher frequencies, the FCC investigated options for increasing the number of broadcasting stations, in addition to ideas for better audio quality, known as "high-fidelity". In 1937 it introduced what became known as the Apex band, consisting of 75 broadcasting frequencies from 41.02 to 43.98 MHz. As on the standard broadcast band, these were AM stations but with higher quality audio – in one example, a frequency response from 20 Hz to 17,000 Hz +/- 1 dB – because station separations were 40 kHz instead of the 10 kHz spacings used on the original AM band. Armstrong worked to convince the FCC that a band of FM broadcasting stations would be a superior approach. That year he financed the construction of the first FM radio station, W2XMN (later

In the late 1930s, as technical advances made it possible to transmit on higher frequencies, the FCC investigated options for increasing the number of broadcasting stations, in addition to ideas for better audio quality, known as "high-fidelity". In 1937 it introduced what became known as the Apex band, consisting of 75 broadcasting frequencies from 41.02 to 43.98 MHz. As on the standard broadcast band, these were AM stations but with higher quality audio – in one example, a frequency response from 20 Hz to 17,000 Hz +/- 1 dB – because station separations were 40 kHz instead of the 10 kHz spacings used on the original AM band. Armstrong worked to convince the FCC that a band of FM broadcasting stations would be a superior approach. That year he financed the construction of the first FM radio station, W2XMN (later KE2XCC

KE2XCC, first authorized in 1945 with the call sign W2XEA, was an experimental FM radio station located in Alpine, New Jersey and operated by inventor Edwin Howard Armstrong. It was located at the same site as Armstrong's original FM station, W2 ...

) at Alpine, New Jersey. FCC engineers had believed that transmissions using high frequencies would travel little farther than line-of-sight distances, limited by the horizon. When operating with 40 kilowatts on 42.8 MHz, the station could be clearly heard away, matching the daytime coverage of a full power 50-kilowatt AM station.

FCC studies comparing the Apex station transmissions with Armstrong's FM system concluded that his approach was superior. In early 1940, the FCC held hearings on whether to establish a commercial FM service. Following this review, the FCC announced the establishment of an FM band effective January 1, 1941, consisting of forty 200 kHz-wide channels on a band from 42 to 50 MHz, with the first five channels reserved for educational stations. Existing Apex stations were notified that they would not be allowed to operate after January 1, 1941, unless they converted to FM.

Although there was interest in the new FM band by station owners, construction restrictions that went into place during WWII limited the growth of the new service. Following the end of WWII, the FCC moved to standardize its frequency allocations. One area of concern was the effects of tropospheric and Sporadic E propagation, which at times reflected station signals over great distances, causing mutual interference. A particularly controversial proposal, spearheaded by RCA, was that the FM band needed to be shifted to higher frequencies to avoid this problem. This reassignment was fiercely opposed as unneeded by Armstrong, but he lost. The FCC made its decision final on June 27, 1945. It allocated 100 FM channels from 88 to 108 MHz, and assigned the former FM band to 'non government fixed and mobile' (42–44 MHz), and television channel 1 (44–50 MHz), now sidestepping the interference concerns. A period of allowing existing FM stations to broadcast on both low and high bands ended at midnight on January 8, 1949, at which time any low band transmitters were shut down, making obsolete 395,000 receivers that had already been purchased by the public for the original band. Although converters allowing low band FM sets to receive high band were manufactured, they ultimately proved to be complicated to install, and often as (or more) expensive than buying a new high band set outright.

Armstrong felt the FM band reassignment had been inspired primarily by a desire to cause a disruption that would limit FM's ability to challenge the existing radio industry, including RCA's AM radio properties that included the NBC radio network, plus the other major networks including CBS, ABC and Mutual. The change was thought to have been favored by AT&T, as the elimination of FM relaying stations would require radio stations to lease wired links from that company. Particularly galling was the FCC assignment of TV channel 1 to the 44–50 MHz segment of the old FM band. Channel 1 was later deleted, since periodic radio propagation

Radio propagation is the behavior of radio waves as they travel, or are wave propagation, propagated, from one point to another in vacuum, or into various parts of the atmosphere.

As a form of electromagnetic radiation, like light waves, radio w ...

would make local TV signals unviewable.

Although the FM band shift was an economic setback, there was reason for optimism. A book published in 1946 by Charles A. Siepmann heralded FM stations as "Radio's Second Chance". In late 1945, Armstrong contracted with John Orr Young, founding member of the public relations firm Young & Rubicam

VMLY&R was an American marketing and Marketing communications, communications company specializing in advertising, Digital media, digital and social media, sales promotion, direct marketing and brand identity consulting, formed from the 2020 mer ...

, to conduct a national campaign promoting FM broadcasting, especially by educational institutions. Article placements promoting both Armstrong personally and FM were made with general circulation publications including ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'', ''Fortune

Fortune may refer to:

General

* Fortuna or Fortune, the Roman goddess of luck

* Luck

* Wealth

* Fate

* Fortune, a prediction made in fortune-telling

* Fortune, in a fortune cookie

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Fortune'' (19 ...

'', ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', '' Atlantic Monthly'', and ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine published six times a year. It was published weekly from 1897 until 1963, and then every other week until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely circulated and influ ...

''.

In 1940, RCA offered Armstrong $1,000,000 for a non-exclusive, royalty-free license to use his FM patents. He refused this offer, because he felt this would be unfair to the other licensed companies, which had to pay 2% royalties on their sales. Over time this impasse with RCA dominated Armstrong's life. RCA countered by conducting its own FM research, eventually developing what it claimed was a non-infringing FM system. The corporation encouraged other companies to stop paying royalties to Armstrong. Outraged by this, in 1948 Armstrong filed suit against RCA and the National Broadcasting Company, accusing them of patent infringement and that they had "deliberately set out to oppose and impair the value" of his invention, for which he requested treble damages. Although he was confident that this suit would be successful and result in a major monetary award, the protracted legal maneuvering that followed eventually began to impair his finances, especially after his primary patents expired in late 1950.

FM radar

During World War II, Armstrong turned his attention to investigations of continuous-wave FM radar funded by government contracts. Armstrong hoped that the interference fighting characteristic of wide-band FM and a narrow receiver bandwidth to reduce noise would increase range. Primary development took place at Armstrong's Alpine, NJ laboratory. A duplicate set of equipment was sent to the U.S. Army's Evans Signal Laboratory. The results of his investigations were inconclusive, the war ended, and the project was dropped by the Army. Under the nameProject Diana

Project Diana, named for the Roman moon goddess Diana, was an experimental project of the US Army Signal Corps in 1946 to bounce radar signals off the Moon and receive the reflected signals. This was the first experiment in radar astronomy ...

, the Evans staff took up the possibility of bouncing radar signals off the moon. Calculations showed that standard pulsed radar like the stock SCR-271 would not do the job; higher average power, much wider transmitter pulses, and very narrow receiver bandwidth would be required. They realized that the Armstrong equipment could be modified to accomplish the task. The FM modulator of the transmitter was disabled and the transmitter keyed to produce quarter-second CW pulses. The narrow-band (57 Hz) receiver, which tracked the transmitter frequency, got an incremental tuning control to compensate for the possible 300 Hz Doppler shift on the lunar echoes. They achieved success on January 10, 1946.

Death

The numerous protracted patent fights caused Armstrong's health to suffer and his behavior grew erratic. On one occasion he came to believe that someone had poisoned his food and insisted on having his stomach pumped. According to ''They Made America'' – authored by Sir Harold Evans and others – Armstrong was oblivious to the toll his struggle was taking on Marion. Marion spent months in a mental hospital after she threw herself into theEast River

The East River is a saltwater Estuary, tidal estuary or strait in New York City. The waterway, which is not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates Long Island, ...

.

The legal battles also brought Armstrong to the brink of financial ruin. On November 1, 1953, Armstrong told Marion that he had used up almost all his financial resources.

In better times, funds for their retirement were put in her name, and he asked her to release a portion of those funds so he could continue litigation. She declined, and suggested he consider accepting a settlement. Enraged, Armstrong picked up a fireplace poker, striking her on the arm. Marion left the apartment to stay with her sister and never saw Armstrong again.

After just under three months of separation from Marion, sometime during the night of January 31February 1, 1954, Armstrong jumped to his death from a window in his 12-room apartment on the 13th floor of River House in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

, New York City. The ''New York Times'' described the contents of his two-page suicide note to his wife: "he was heartbroken at being unable to see her once again, and expressing deep regret at having hurt her, the dearest thing in his life." The note concluded, "God keep you and Lord have mercy on my Soul."

David Sarnoff

David Sarnoff (February 27, 1891 – December 12, 1971) was a Russian and American businessman who played an important role in the American history of radio and television. He led the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) for most of his career in ...

disclaimed any responsibility, telling Carl Dreher directly that "I did not kill Armstrong." After his death, a friend of Armstrong estimated that 90 percent of his time was spent on litigation against RCA. U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

(R-Wisconsin) reported that Armstrong had recently met with one of his investigators, and had been "mortally afraid" that secret radar discoveries by him and other scientists "were being fed to the Communists as fast as they could be developed".

Following her husband's suicide, Marion Armstrong took charge of pursuing his estate's legal cases. In late December 1954, it was announced that through arbitration

Arbitration is a formal method of dispute resolution involving a third party neutral who makes a binding decision. The third party neutral (the 'arbitrator', 'arbiter' or 'arbitral tribunal') renders the decision in the form of an 'arbitrati ...

a settlement of "approximately $1,000,000" had been made with RCA. Dana Raymond of Cravath, Swaine & Moore in New York served as counsel in that litigation. Marion Armstrong was able to formally establish Armstrong as the inventor of FM following protracted court proceedings over five of his basic FM patents, with a series of successful suits, which lasted until 1967, against other companies that were found guilty of infringement.

Legacy

It was not until the 1960s that FM stations in the United States started to challenge the popularity of the AM band, helped by the development of FM stereo by General Electric, followed by the FCC's FM Non-Duplication Rule, which limited large-city broadcasters with AM and FM licenses to simulcasting on those two frequencies for only half of their broadcast hours. Armstrong's FM system was also used for communications betweenNASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

and the Apollo program

The Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo, was the United States human spaceflight program led by NASA, which Moon landing, landed the first humans on the Moon in 1969. Apollo followed Project Mercury that put the first Americans in sp ...

astronauts.

A US Postage Stamp was released in his honor in 1983 in a series commemorating American Inventors.

Armstrong has been called "the most prolific and influential inventor in radio history". The superheterodyne process is still extensively used by radio equipment. Eighty years after its invention, FM technology has started to be supplemented, and in some cases replaced, by more efficient digital technologies. The introduction of digital television eliminated the FM audio channel that had been used by analog television, HD Radio

HD Radio (HDR) is a trademark for in-band on-channel (IBOC) digital radio broadcast technology. HD radio generally simulcast, simulcasts an existing analog radio station in digital format with less noise and with additional text information. HD R ...

has added digital sub-channels to FM band stations, and, in Europe and Pacific Asia, Digital Audio Broadcasting

Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB) is a digital radio international standard, standard for broadcasting digital audio radio services in many countries around the world, defined, supported, marketed and promoted by the WorldDAB organisation. T ...

bands have been created that will, in some cases, eliminate existing FM stations altogether. However, FM broadcasting is still used internationally, and remains the dominant system employed for audio broadcasting services.

Personal life

In 1923, combining his love for high places with courtship rituals, Armstrong climbed the WJZ (now WABC) antenna located atop a 20-story building in New York City, where he reportedly did a handstand, and when a witness asked him what motivated him to "do these damnfool things", Armstrong replied "I do it because the spirit moves me." Armstrong had arranged to have photographs taken, which he had delivered to David Sarnoff's secretary, Marion McInnis. Armstrong and McInnis married later that year. Armstrong bought aHispano-Suiza

Hispano-Suiza () is a Spanish automotive company. It was founded in 1904 by Marc Birkigt and as an automobile manufacturer and eventually had several factories in Spain and France that produced luxury cars, aircraft engines, trucks and weapons. ...

motor car before the wedding, which he kept until his death, and which he drove to Palm Beach, Florida for their honeymoon. A publicity photograph was made of him presenting Marion with the world's first portable superheterodyne radio as a wedding gift.

He was an avid tennis player until an injury in 1940, and drank an Old Fashioned with dinner. Politically, he was described by one of his associates as "a revolutionist only in technology – in politics he was one of the most conservative of men."

In 1955, Marion Armstrong founded the Armstrong Memorial Research Foundation, and participated in its work until her death in 1979 at the age of 81. She was survived by two nephews and a niece.

Honors

Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

.

For his wartime work on radio, the French government gave him the Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

in 1919. He was awarded the 1941 Franklin Medal, and in 1942 received the AIEEs Edison Medal "for distinguished contributions to the art of electric communication, notably the regenerative circuit, the superheterodyne, and frequency modulation." The ITU added him to its roster of great inventors of electricity in 1955.

He later received two honorary doctorates, from Columbia in 1929, and Muhlenberg College in 1941.

In 1980, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and appeared on a U.S. postage stamp in 1983. The Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame inducted him in 2000, "in recognition of his contributions and pioneering spirit that have laid the foundation for consumer electronics."

He was posthumously inducted into the Wireless Hall of Fame in 2001. Columbia University established the Edwin Howard Armstrong Professorship

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a 'person who professes'. Professors ...

in the School of Engineering and Applied Science in his memory.

Philosophy Hall, the Columbia building where Armstrong developed FM, was declared a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

. Armstrong's boyhood home in Yonkers, New York was recognized by the National Historic Landmark program and the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

, although this was withdrawn when the house was demolished. (includes 1 photo)

Armstrong Hall at Columbia was named in his honor. The hall, located at the northeast corner of Broadway and 112th Street, was originally an apartment house but was converted to research space after being purchased by the university. It is currently home to the Goddard Institute for Space Studies

The Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) is a laboratory in the Earth Sciences Division of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center affiliated with the Columbia University Earth Institute.

The institute is located at Columbia University in Ne ...

, a research institute dedicated to atmospheric and climate science that is jointly operated by Columbia and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the United States's civil space program, aeronautics research and space research. Established in 1958, it su ...

. A storefront in a corner of the building houses Tom's Restaurant, a longtime neighborhood fixture that inspired Susanne Vega's song " Tom's Diner" and was used for establishing shots for the fictional "Monk's diner" in the "Seinfeld

''Seinfeld'' ( ) is an American television sitcom created by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld that originally aired on NBC from July 5, 1989, to May 14, 1998, with a total of nine seasons consisting of List of Seinfeld episodes, 180 episodes. It ...

" television series.

A second Armstrong Hall, also named for the inventor, is located at the United States Army Communications and Electronics Life Cycle Management Command (CECOM-LCMC) Headquarters at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland.

In 2005, Armstrong's regenerative feedback circuit and superheterodyne and FM circuits were inducted into the TECnology Hall of Fame, an honor given to "products and innovations that have had an enduring impact on the development of audio technology."

Patents

E. H. Armstrong patents: * : "Frequency Modulation Multiplex System" * : "Radio Signaling" * : "Frequency-Modulated Carrier Signal Receiver" * : "Frequency Modulation Signaling System" * : "Means for Receiving Radio Signals" * : "Method and Means for Transmitting Frequency Modulated Signals" * : "Current Limiting Device" * : "Frequency Modulation System" * : "Radio Rebroadcasting System" * : "Means and Method for Relaying Frequency Modulated Signals" * : "Means and Method for Relaying Frequency Modulated Signals" * : "Frequency Modulation Signaling System" * : "Radio Transmitting System" * : "Radio Transmitting System" * : "Radio Transmitting System" * : "Frequency Changing System" * : "Radio Receiving System" * : "Radio Receiving System" * : "Multiplex Radio Signaling System" * : "Radio Signaling System" * : "Radio Transmitting System" * : "Phase Control System" * : "Radio Signaling System" * : "Radio Transmitting System" * : "Radio Signaling System" * : "Radio Telephone Signaling" * : "Radiosignaling" * : "Radiosignaling" * : "Radio Broadcasting and Receiving System" * : "Radio Signaling System" * : "Wave Signaling System" * : "Wave Signaling System" * : "Wireless Receiving System for Continuous Wave" * : "Wave Signaling System" * : "Wave Signaling System" * : "Wave Signaling System" * : "Wave Signaling System" * : "Wave Signaling System" * : "Signaling System" * : "Radioreceiving System Having High Selectivity" * : "Selectively Opposing Impedance to Received Electrical Oscillations" * : "Multiple Antenna for Electrical Wave Transmission" * : "Method of Receiving High Frequency Oscillation" * : "Antenna with Distributed Positive Resistance" * : "Electric Wave Transmission" (Note: Co-patentee with Mihajlo Pupin) * : "Wireless Receiving System" U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Database Search The following patents were issued to Armstrong's estate after his death: * : "Radio detection and ranging systems" 1956 * : "Multiplex frequency modulation transmitter" 1956 * : "Linear detector for subcarrier frequency modulated waves" 1958 * : "Noise reduction in phase shift modulation" 1959 * : "Stabilized multiple frequency modulation receiver" 1959 Kraeuter, David. Radio Patent Lists and Index 1830-1980, 2001, p. 23See also

* Awards named after E. H. Armstrong * Grid-leak detectorNotes

References

* * Frost, Gary L. (2010), ''Early FM Radio: Incremental Technology in Twentieth-Century America.'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. , . * * * *Further reading

* Ira Brodsky. ''The History of Wireless: How Creative Minds Produced Technology for the Masses.'' St. Louis: Telescope Books, 2008. *Ken Burns

Kenneth Lauren Burns (born July 29, 1953) is an American filmmaker known for his documentary films and television series, many of which chronicle American history and culture. His work is often produced in association with WETA-TV or the Nati ...

Empire of the Air

. Documentary that first aired on PBS in 1992. *

External links

*Armstrong Memorial Research Foundation

– The Armstrong Foundation disseminates knowledge of Armstrong's research and achievements

Houck Collection

– A collection of images and documents that belonged to Armstrong's assistant, Harry W. Houck, which have been annotated by Mike Katzdorn.

Rare Book & Manuscript Library Collections

– A collection of images and documents at Columbia University

– A brief biography by Donna Halper * Ammon, Richard T., "

The Rolls Royce Of Reception

: Super Heterodynes – 1918 to 1930''". * IEEE History Center'

Edwin H. Armstrong

: Excerpt from "The Legacy of Edwin Howard Armstrong," by J. E. Brittain Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 79, no. 2, February 1991 * Hong, Sungook, "

A History of the Regeneration Circuit: From Invention to Patent Litigation

'" University, Seoul, Korea (PDF)

Who Invented the Superhetrodyne?

The history of the invention of the superhetrodyne receiver and related patent disputes * Yannis Tsividis,

, 2002. A profile on the web site of

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, Armstrong's alma mater

{{DEFAULTSORT:Armstrong, Edwin

1890 births

1954 suicides

1954 deaths

20th-century American inventors

American electronics engineers

United States Army personnel of World War I

American Presbyterians

American telecommunications engineers

Analog electronics engineers

Knights of the Legion of Honour

Columbia School of Engineering and Applied Science alumni

Columbia School of Engineering and Applied Science faculty

Discovery and invention controversies

History of radio in the United States

IEEE Medal of Honor recipients

IEEE Edison Medal recipients

People from Yonkers, New York

Radio electronics

Radio pioneers

United States Army Signal Corps personnel

Military personnel from New York (state)

Suicides by jumping in New York City

People from Chelsea, Manhattan

United States Army officers

Recipients of Franklin Medal