Dreadnought hoax on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Dreadnought'' hoax was a

The ''Dreadnought'' hoax was a

In early 1905, while at their second year at

In early 1905, while at their second year at

In the early 20th century, Britain's naval fleet was seen as one of the foundations of its empire, and a reflection of the country's power and wealth. As Britain was portrayed in books, plays and popular culture as an island nation, the

In the early 20th century, Britain's naval fleet was seen as one of the foundations of its empire, and a reflection of the country's power and wealth. As Britain was portrayed in books, plays and popular culture as an island nation, the

The ''Dreadnought'' hoax was a

The ''Dreadnought'' hoax was a prank

A practical joke, or prank, is a mischievous trick played on someone, generally causing the victim to experience embarrassment, perplexity, confusion, or discomfort.Marsh, Moira. 2015. ''Practically Joking''. Logan: Utah State University Press. ...

pulled by Horace de Vere Cole

William Horace de Vere Cole (5 May 1881 – 25 February 1936) was an eccentric prankster born in Ballincollig, County Cork, Ireland. His most famous prank was the ''Dreadnought'' hoax where he and several others in blackface, pretending to b ...

in 1910. Cole tricked the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

into showing their flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

, the battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

HMS ''Dreadnought'', to a fake delegation of " Abyssinian royals". The hoax drew attention in Britain to the emergence of the Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group—or Bloomsbury Set—was a group of associated English writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the first half of the 20th century, including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster and Lytton St ...

, among whom some of Cole's collaborators numbered. The hoax was a repeat of a similar impersonation which Cole and Adrian Stephen

Adrian Leslie Stephen (27 October 1883 – 3 May 1948) was a member of the Bloomsbury Group, an author and psychoanalyst, and the younger brother of Thoby Stephen, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. He and his wife Karin Stephen became interested ...

had organised while they were students at Cambridge in 1905.

Background

Hoaxers

Horace de Vere Cole

William Horace de Vere Cole (5 May 1881 – 25 February 1936) was an eccentric prankster born in Ballincollig, County Cork, Ireland. His most famous prank was the ''Dreadnought'' hoax where he and several others in blackface, pretending to b ...

was born in Ireland in 1881 to a well-to-do family. He was commissioned into the Yorkshire Hussars and served in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

, where he was seriously wounded and invalided out of service. On his return to Britain he became an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

; he studied little, and spent his time entertaining and undertaking hoaxes and pranks.

One of Cole's closest friends at Trinity was Adrian Stephen

Adrian Leslie Stephen (27 October 1883 – 3 May 1948) was a member of the Bloomsbury Group, an author and psychoanalyst, and the younger brother of Thoby Stephen, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. He and his wife Karin Stephen became interested ...

, a keen sportsman and actor. Cole's biographer, Martyn Downer, considers that Stephen was a "perfect foil for ... ole someone sympathetic and encouraging yet unafraid to take him on". Stephen was the son of Leslie, the writer and critic, and Julia, the philanthropist and Pre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Jam ...

model. Adrian Stephen's elder brother, Thoby was also at Trinity, and their sisters, Vanessa (later Vanessa Bell) and Virginia (later Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born ...

) would visit. After university the four Stephen siblings became members of the Bloomsbury Group

The Bloomsbury Group—or Bloomsbury Set—was a group of associated English writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the first half of the 20th century, including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster and Lytton St ...

, the set of associated writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists, many of whose members had also been at Trinity College. Cole was on the fringes of the group, but never a member.

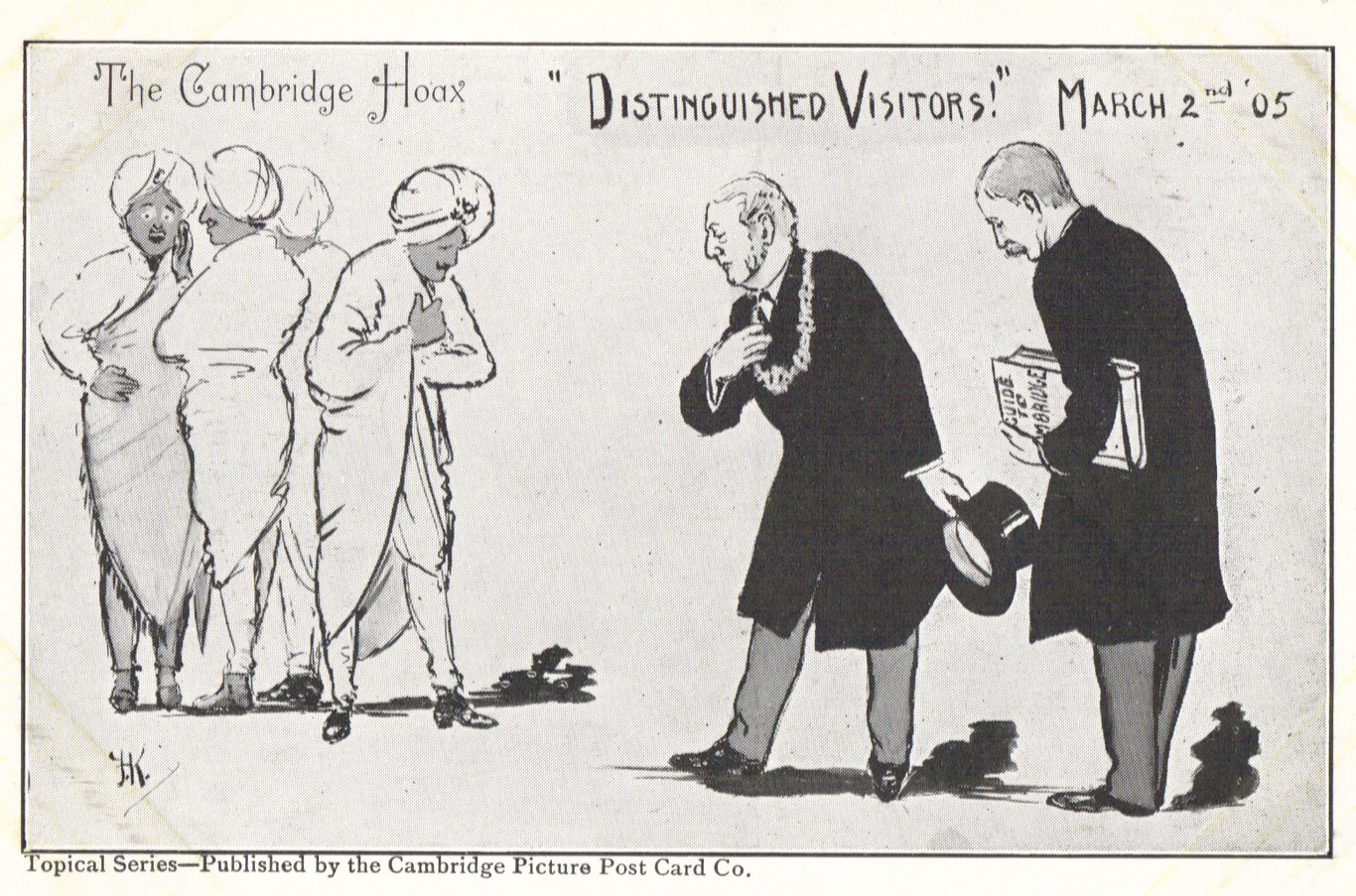

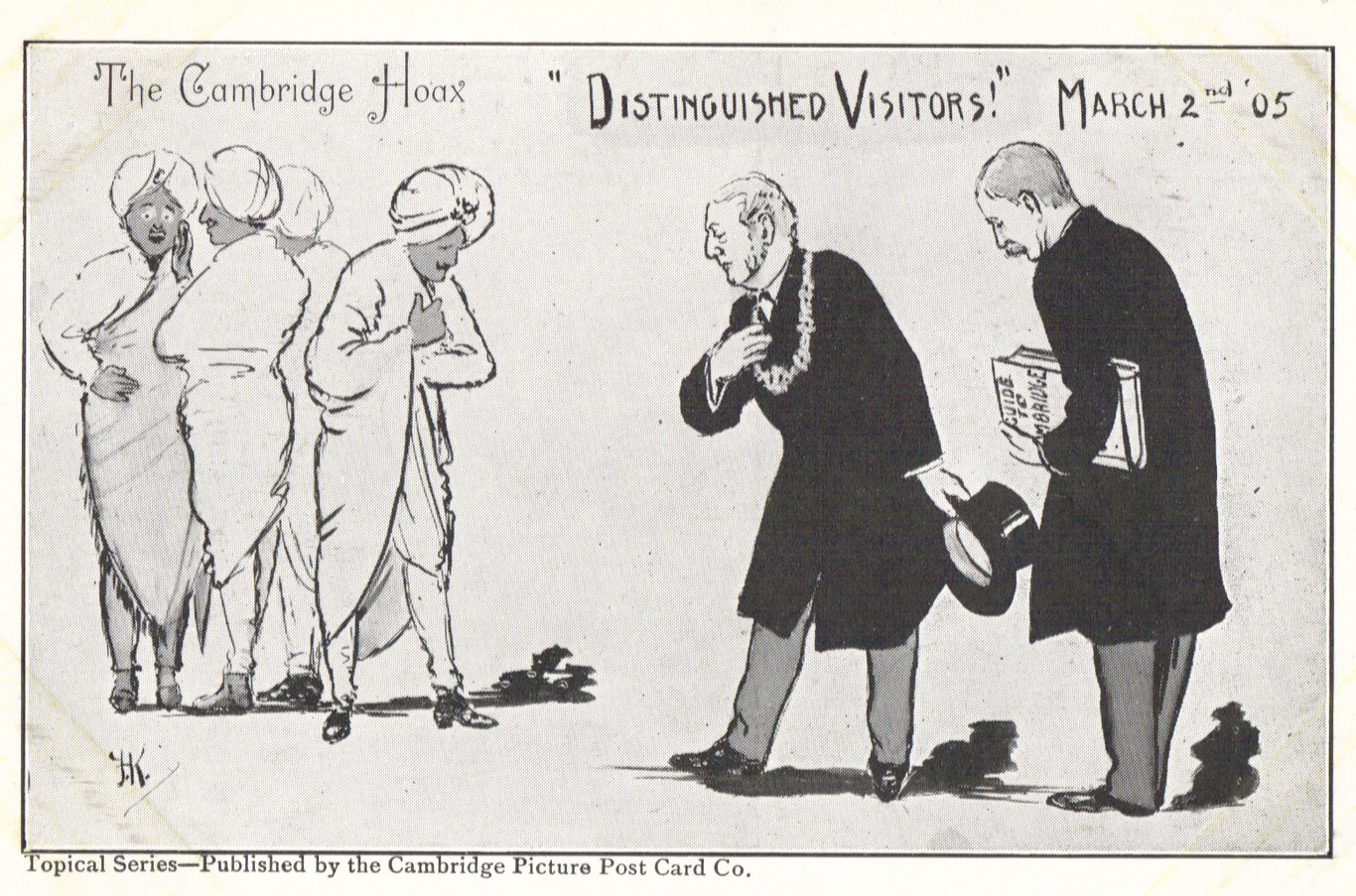

Cambridge Zanzibar hoax

In early 1905, while at their second year at

In early 1905, while at their second year at Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, Cole and Adrian Stephen decided to use a visit to England of Sayyid Ali bin Hamud Al-Busaid, the eighth Sultan of Zanzibar as the basis for a hoax. A plan was put together to fake a state visit

A state visit is a formal visit by a head of state to a foreign country, at the invitation of the head of state of that foreign country, with the latter also acting as the official host for the duration of the state visit. Speaking for the host ...

of the sultan to Cambridge, although they realised that as the sultan's picture had recently appeared in the press, there was a risk the visiting sultan would be shown as a fraud. They decided that Cole would impersonate the sultan's uncle, rather than the sultan. On 2 March they sent a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

to the Mayor of Cambridge to ask if he could arrange a suitable reception for the sultan:

The students obtained robes and turbans from the theatrical costumier Willy Clarkson

William Berry "Willy" Clarkson (31 March 1861 - 12/13 October 1934) was a British theatrical costume designer and wigmaker.

Career

Clarkson's father had been making wigs since 1833. Willie Clarkson was educated in Paris but left school at the ...

, applied blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

make-up and took the train from London. A carriage met the group at Cambridge railway station

Cambridge railway station is the principal station serving the city of Cambridge in the east of England. It stands at the end of Station Road, south-east of the city centre. It is the northern terminus of the West Anglia Main Line, down ...

and took them to the guildhall, where they were met by the mayor and town clerk. After a brief reception they were taken on a tour of the town, including some of the university's colleges; the hoaxers were seen by some of their friends and acquaintances who did not recognise them. After less than an hour they demanded to be returned to the station. As they did not want to return to London—returning from which would have meant them breaking the 10:00pm college curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

—on arrival at the station they ran out of a side exit and took two hansom cab

The hansom cab is a kind of horse-drawn carriage designed and patented in 1834 by Joseph Hansom, an architect from York. The vehicle was developed and tested by Hansom in Hinckley, Leicestershire, England. Originally called the Hansom safety ca ...

s to a friend's house, where they changed back into their normal attire.

The following day Cole gave an interview to the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' about the hoax; the story appeared in the paper on 4 March 1905, and was repeated in local newspapers. The ''St James's Gazette

The ''St James's Gazette'' was a London evening newspaper published from 1880 to 1905. It was founded by the Conservative Henry Hucks Gibbs, later Baron Aldenham, a director of the Bank of England 1853–1901 and its governor 1875–1877; the ...

'' considered the events "a most audacious practical joke." The Mayor wanted the students involved to be sent down, but was persuaded by the Vice-Chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth and former Commonwealth nations, the chancellor ...

that this would damage his reputation further.

Dreadnoughts and the Royal Navy

In the early 20th century, Britain's naval fleet was seen as one of the foundations of its empire, and a reflection of the country's power and wealth. As Britain was portrayed in books, plays and popular culture as an island nation, the

In the early 20th century, Britain's naval fleet was seen as one of the foundations of its empire, and a reflection of the country's power and wealth. As Britain was portrayed in books, plays and popular culture as an island nation, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

was seen as the defender of the island, and its first line of defence. A leading article

An editorial, or leading article (UK) or leader (UK) is an article written by the senior editorial people or publisher of a newspaper, magazine, or any other written document, often unsigned. Australian and major United States newspapers, such ...

in ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'' in 1909 described the supremacy of the Royal Navy as "the best security for the world's peace and advancement".

, the first of Britain's "dreadnought" class of battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

, entered into Royal Navy service in 1906. ''Dreadnought'' was the most technologically advanced ship that had been built; it was better armed, faster and stronger than any other vessel afloat. According to the historian Jan Rüger, from the time the ship was launched, it took on cultural significance as a symbol and entered into public consciousness through songs and advertising. When the ship visited London in 1909—part of three fleet reviews held—a million people were estimated to have watched its arrival, and by 1910 it "had become a cultural icon with undeniable symbolic status". Rüger gives examples of advertising for Oxo stock cubes: "Drink OXO and dread nought"; a tailoring business that used the slogan "Dreadnought and wear British clothing"; and "Dreadnought tram

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport ...

s" ran, styled as battleships, and complete with imitation guns. The cultural historian Elisa deCourcy describes the ''Dreadnought'' as having "a near sacrosanct nature" for the Edwardians.

In February 1910 the captain of ''Dreadnought'' was Herbert Richmond

Admiral Sir Herbert William Richmond, (15 September 1871 – 15 December 1946) was a prominent Royal Navy officer, described as "perhaps the most brilliant naval officer of his generation." He was also a top naval historian, known as the "Briti ...

; Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

Sir William May was the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the Firs ...

; as such, ''Dreadnought'' was his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

. Also present on ''Dreadnought'' was Commander Willie Fisher—the Stephens' cousin—who was on the staff of the Admiral.

Hoax

upright=1.2, The ''Dreadnought'' hoaxers in Abyssinian costume In a talk given in 1940, Woolf described how, in 1910, young naval officers enjoyed playingpractical joke

A practical joke, or prank, is a mischievous trick played on someone, generally causing the victim to experience embarrassment, perplexity, confusion, or discomfort.Marsh, Moira. 2015. ''Practically Joking''. Logan: Utah State University Press. ...

s on one another:

This involved Cole and five friends—writer Virginia Stephen (later Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born ...

), her brother Adrian Stephen

Adrian Leslie Stephen (27 October 1883 – 3 May 1948) was a member of the Bloomsbury Group, an author and psychoanalyst, and the younger brother of Thoby Stephen, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. He and his wife Karin Stephen became interested ...

, Guy Ridley, Anthony Buxton and artist Duncan Grant

Duncan James Corrowr Grant (21 January 1885 – 8 May 1978) was a British painter and designer of textiles, pottery, theatre sets and costumes. He was a member of the Bloomsbury Group.

His father was Bartle Grant, a "poverty-stricken" major i ...

—who had themselves disguised by the theatrical costumier Willy Clarkson

William Berry "Willy" Clarkson (31 March 1861 - 12/13 October 1934) was a British theatrical costume designer and wigmaker.

Career

Clarkson's father had been making wigs since 1833. Willie Clarkson was educated in Paris but left school at the ...

with skin darkeners and turbans to resemble members of the Abyssinian royal family. The main limitation of the disguises was that the "royals" could not eat anything or their make-up would be ruined. Adrian Stephen took the role of "interpreter".

On 7 February 1910 Clarkson's employees visited Woolf's home and applied the stage make-up to Woolf, Grant, Buxton and Ridley, then provided eastern robes. According to the ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily Tabloid journalism, tabloid. Founded in 1903, it is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the title on its Masthead (British publishing), masthead was simpl ...

'', they were also wearing £500 of jewellery; Martin Downer, in his biography of Cole, doubts the amount, which is not repeated by any of the participants.

A friend of Stephen's sent a telegram to the "C-in-C, Home Fleet" ( Commander-in-chief of the vessels defending Britain)

stating that "Prince Makalen of Abbysinia ' and suite arrive 4.20 today Weymouth. He wishes to see Dreadnought. Kindly arrange meet them on arrival"; the message was signed "Harding Foreign Office". Cole had found a post office that was staffed only by women, as he thought they were less likely to ask questions about the message. Cole with his entourage went to London's Paddington station where Cole claimed that he was "Herbert Cholmondeley" of the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

and demanded a special train to Weymouth; the stationmaster arranged a VIP coach.

In Weymouth, the navy welcomed the princes with an honour guard

A guard of honour ( GB), also honor guard ( US), also ceremonial guard, is a group of people, usually military in nature, appointed to receive or guard a head of state or other dignitaries, the fallen in war, or to attend at state ceremonials, ...

. An Abyssinian flag was not found, so the navy proceeded to use that of Zanzibar and to play Zanzibar's national anthem.

The group inspected the fleet. To show their appreciation, they communicated in a gibberish of words drawn from Latin and Greek; they asked for prayer mats and attempted to bestow fake military honours

A military funeral is a memorial or burial rite given by a country's military for a soldier, sailor, marine or airman who died in battle, a veteran, or other prominent military figures or heads of state. A military funeral may feature guards ...

on some of the officers. Commander Fisher failed to recognise either of his cousins.

The hoax was widely reported, and the navy mocked

When the prank was uncovered in London, the ringleader Horace de Vere Cole

William Horace de Vere Cole (5 May 1881 – 25 February 1936) was an eccentric prankster born in Ballincollig, County Cork, Ireland. His most famous prank was the ''Dreadnought'' hoax where he and several others in blackface, pretending to b ...

contacted the press and sent a photo of the "princes" to the ''Daily Mirror''. The group's pacifist views were considered a source of embarrassment, and the Royal Navy briefly became an object of ridicule. The Navy later demanded that Cole be arrested. However, Cole and his compatriots had not broken any law. Instead, with the exception of Virginia Woolf, they were subjected to a symbolic thrashing on the buttocks by junior Royal Navy officers.

Aftermath

According to press reports, during the visit to ''Dreadnought'', the visitors repeatedly showed amazement or appreciation by exclaiming "Bunga Bunga

Bunga bunga is a phrase of uncertain origin and various meanings that dates from 1910, and a name for an area of Australia dating from 1852. By 2010 the phrase had gained popularity in Italy and the international press to refer to then-Italian Pri ...

!" In 1915 during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, HMS ''Dreadnought'' rammed and sank a German submarine—the only battleship ever to do so. Among the telegrams of congratulation was one that read "BUNGA BUNGA"..

A song was heard in music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Br ...

s that year, sung to the tune of " The Girl I Left Behind"

Thirty years later, in 1940, Virginia Woolf gave talks about the ''Dreadnought'' hoax to the Rodmell Women's Institute and also to the Memoir Club

The Bloomsbury Group—or Bloomsbury Set—was a group of associated English writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the first half of the 20th century, including Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster and Lytton Strac ...

, the latter attended by E. M. Forster.

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

Books

* * * * * *Journals

* * * * * *News articles

* * * * * *Websites

* {{Virginia Woolf, state=collapsed 1910 in the United Kingdom Hoaxes in the United Kingdom February 1910 events 1910 in international relations History of the Royal Navy 1910s hoaxes 1910 in England Virginia Woolf