Dixiecrats on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The States' Rights Democratic Party (whose members are often called the Dixiecrats) was a short-lived

Since the beginning of Reconstruction, Southern white voters supported the Democratic Party by overwhelming margins in both local and national elections, (the few exceptions include minor pockets of

Since the beginning of Reconstruction, Southern white voters supported the Democratic Party by overwhelming margins in both local and national elections, (the few exceptions include minor pockets of

Prior to their own States' Rights Democratic Party convention, it was not clear whether the Dixiecrats would seek to field their own candidate or simply try to prevent Southern electors from voting for Truman. Many in the press predicted that if the Dixiecrats did nominate a ticket,

Prior to their own States' Rights Democratic Party convention, it was not clear whether the Dixiecrats would seek to field their own candidate or simply try to prevent Southern electors from voting for Truman. Many in the press predicted that if the Dixiecrats did nominate a ticket,

/ref> In the 1960 presidential election, Republican

Dixiecrats

''New Georgia Encyclopedia''

1948 Platform of Oklahoma's Dixiecrats

{{Authority control Defunct political parties in the United States History of the Southern United States Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Strom Thurmond Political terminology of the United States Democratic Party (United States) White supremacy in the United States Political parties established in 1948 Political repression in the United States 1948 establishments in the United States Political parties disestablished in 1948 1948 disestablishments in the United States 1948 United States presidential election Politics of the Southern United States Protestant political parties White nationalist parties

segregationist

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Interna ...

political party in the United States, active primarily in the South. It arose due to a Southern regional split in opposition to the Democratic Party. After President Harry S. Truman, a member of the Democratic Party, ordered integration of the military in 1948 and other actions to address civil rights of African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, many Southern conservative white politicians who objected to this course organized themselves as a breakaway faction. The Dixiecrats wished to protect Southern states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

to maintain racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

.

Supporters assumed control of the state Democratic parties in part or in full in several Southern states. The Party opposed racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportuni ...

and wanted to retain Jim Crow law

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

s and white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

in the face of possible federal intervention. Its members were referred to as "Dixiecrats", a portmanteau

A portmanteau word, or portmanteau (, ) is a blend of wordsDixie

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas shift over the years), or the extent of the area it cove ...

", referring to the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, and "Democrat".

Despite the Dixiecrats' success in several states, Truman was narrowly re-elected. After the 1948 election, its leaders generally returned to the Democratic Party. The Dixiecrats' presidential candidate, Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Car ...

, became a Republican in 1964. The Dixiecrats represented the weakening of the "Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

". (This referred to the Southern Democratic Party's control of presidential elections in the South and most seats in Congress, partly through decades of disfranchisement of blacks entrenched by Southern state legislatures between 1890 and 1908. Blacks had formerly been aligned with the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

before being excluded from politics in the region, but during the Great Migration African Americans had found the Democratic Party in the North and West more suited to their interests.)

Background

Since the beginning of Reconstruction, Southern white voters supported the Democratic Party by overwhelming margins in both local and national elections, (the few exceptions include minor pockets of

Since the beginning of Reconstruction, Southern white voters supported the Democratic Party by overwhelming margins in both local and national elections, (the few exceptions include minor pockets of Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

electoral strength in Appalachia

Appalachia () is a cultural region in the Eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York State to northern Alabama and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Newfoundland and Labrador, C ...

, East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

in particular, Gillespie and Kendall Counties of central Texas) forming what was known as the "Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

". Even during the last years of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Democrats used paramilitary insurgents and other activists to disrupt and intimidate Republican freedman

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

voters, including fraud at the polls and attacks on their leaders. The electoral violence culminated in the Democrats regaining control of the state legislatures and passing new constitutions and laws from 1890 to 1908 to disenfranchise most blacks and many poor whites. They also imposed Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sou ...

, a combination of legal and informal segregation acts that made blacks second-class citizens, confirming their lack of political power through most of the southern United States. The social and economic systems of the Solid South were based on this structure, although the white Democrats retained all the Congressional seats apportioned for the total population of their states.

Three-time Democratic Party presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

opposed a highly controversial resolution at the 1924 Democratic National Convention

The 1924 Democratic National Convention, held at the Madison Square Garden in New York City from June 24 to July 9, 1924, was the longest continuously running convention in United States political history. It took a record 103 ballots to nomin ...

condemning the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

, expecting the organization would soon fold. Bryan disliked the Klan but never publicly attacked it.

In the 1930s, a political realignment

A political realignment, often called a critical election, critical realignment, or realigning election, in the academic fields of political science and political history, is a set of sharp changes in party ideology, issues, party leaders, regional ...

occurred largely due to the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. While many Democrats in the South had shifted toward favoring economic intervention, civil rights for African Americans was not specifically incorporated within the New Deal agenda, due in part to Southern control over many key positions of power within the U.S. Congress.

With the entry of the United States into the Second World War, Jim Crow was indirectly challenged. More than one and a half million black Americans served in the U.S. military during World War II, where they received equal pay while serving within segregated units, and were equally entitled to receive veterans' benefits after the war. Tens of thousands of black civilians at home were recruited in the labor-starved war industries across many urban centers in the country, mainly due to the promotion of Executive Order 8802

Executive Order 8802 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941, to prohibit ethnic or racial discrimination in the nation's defense industry. It also set up the Fair Employment Practice Committee. It was the first federal ac ...

, which required defense industries not to discriminate based on ethnicity or race.

Members of the Republican Party (which nominated Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor h ...

Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

in 1944 and 1948), along with many Democrats from the northern and western states, supported civil rights legislation that the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

Democrats in Congress almost unanimously opposed. In 2004, Pulitzer prize winning American journalist Les Payne

Leslie Payne (July 12, 1941 – March 19, 2018) was an American journalist. He served as an editor and columnist at ''Newsday'' and was a founder of the National Association of Black Journalists. Payne received a Pulitzer Prize for his investig ...

, wrote that Dixiecrats were affiliated with the KKK and opposed Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

In 2016, David Neiwert

David Neiwert is an American freelance journalist and blogger. He received the National Press Club Award for Distinguished Online Journalism in 2000 for a domestic terrorism series he produced for MSNBC.com. Neiwert has concentrated in part on ex ...

wrote an article for the SPLC

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) is an American 501(c)(3) nonprofit legal advocacy organization specializing in civil rights and public interest litigation. Based in Montgomery, Alabama, it is known for its legal cases against white su ...

saying that "When the members of the Klan were Democrats, as in the 1920s, as well as in the '40s when they called themselves "Dixiecrats," they were conservative Democrats." According to John S. Huntington Ph.D., Southern Democrats formed a far-right faction, the States’ Rights Democratic Party, better known as the Dixiecrats, which became a third-party vehicle for opposing President Harry S. Truman, integration and modern liberalism.

1948 presidential election

After Roosevelt died, the new president Harry S. Truman established a highly visiblePresident's Committee on Civil Rights

The President's Committee on Civil Rights was a United States presidential commission established by President Harry Truman in 1946. The committee was created by Executive Order 9808 on December 5, 1946, and instructed to investigate the status o ...

and issued Executive Order 9981

Executive Order 9981 was issued on July 26, 1948, by President Harry S. Truman. This executive order abolished discrimination "on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin" in the United States Armed Forces, and led to the re-integra ...

to end discrimination in the military in 1948. A group of Southern governors, including Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Car ...

of South Carolina and Fielding L. Wright of Mississippi, met to consider the place of Southerners within the Democratic Party. After a tense meeting with Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

(DNC) chairman and Truman confidant J. Howard McGrath

James Howard McGrath (November 28, 1903September 2, 1966) was an American politician and attorney from Rhode Island. McGrath, a Democrat, served as U.S. Attorney for Rhode Island before becoming governor, U.S. Solicitor General, U.S. Sena ...

, the Southern governors agreed to convene their own convention in Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of the U.S. state of Alabama. Birmingham is the seat of Jefferson County, Alabama's most populous county. As of the 2021 census estimates, Birmingham had a population of 197,575, down 1% f ...

if Truman and civil rights supporters emerged victorious at the 1948 Democratic National Convention

The 1948 Democratic National Convention was held at Philadelphia Convention Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from July 12 to July 14, 1948, and resulted in the nominations of President Harry S. Truman for a full term and Senator Alben W ...

. In July, the convention nominated Truman to run for a full term and adopted a plank proposed by Northern liberals led by Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

calling for civil rights; 35 Southern delegates walked out. The move was on to remove Truman's name from the ballot in the southern United States. This political maneuvering required the organization of a new and distinct political party, which the Southern defectors from the Democratic Party chose to brand as the States' Rights Democratic Party.

Just days after the 1948 Democratic National Convention, the States' Rights Democrats held their own convention at Municipal Auditorium in Birmingham, on July 17. While several leaders from the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

such as Strom Thurmond and James Eastland

James Oliver Eastland (November 28, 1904 February 19, 1986) was an American attorney, plantation owner, and politician from Mississippi. A Democrat, he served in the United States Senate in 1941 and again from 1943 until his resignation on De ...

attended, most major Southern Democrats did not attend the conference. Among those absent were Georgia Senator Richard Russell Jr.

Richard Brevard Russell Jr. (November 2, 1897 – January 21, 1971) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 66th Governor of Georgia from 1931 to 1933 before serving in the United States Senate for almos ...

, who had finished with the second-most delegates in the Democratic presidential ballot.

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

Governor Benjamin Travis Laney

Benjamin Travis Laney, Jr. (November 25, 1896January 21, 1977), was an American businessman who served as the 33rd governor of Arkansas from 1945 to 1949.

Life and career

Laney was born in Camden, where he attended Ouachita County public scho ...

would be the presidential nominee, and South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond or Mississippi Governor Fielding L. Wright the vice presidential nominee. Laney traveled to Birmingham during the convention, but he ultimately decided that he did not want to join a third party and remained in his hotel during the convention. Thurmond himself had doubts about a third-party bid, but party organizers convinced him to accept the party's nomination, with Fielding Wright as his running mate. Wright's supporters had hoped that Wright would lead the ticket, but Wright deferred to Thurmond, who had greater national stature. The selection of Thurmond received fairly positive reviews from the national press, as Thurmond had pursued relatively moderate policies on civil rights and did not employ the fiery rhetoric used by other segregationist leaders.

The States' Rights Democrats did not formally declare themselves as being a new third party, but rather said that they were only "recommending" that state Democratic Parties vote for the Thurmond–Wright ticket. The goal of the party was to win the 127 electoral votes of the Solid South, in the hopes of denying Truman–Barkley or Dewey–Warren an overall majority of electoral votes, and thus throwing the presidential election to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

and the vice presidential election to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

. Once in the House and Senate, the Dixiecrats hoped to throw their support to whichever party would agree to their segregationist demands. Even if the Republican ticket won an outright majority of electoral votes (as many expected in 1948), the Dixiecrats hoped that their third-party run would help the South retake its dominant position in the Democratic Party. In implementing their strategy, the States' Rights Democrats faced a complicated set of state election laws, with different states having different processes for choosing presidential electors. The States' Rights Democrats eventually succeeded in making the Thurmond–Wright ticket the official Democratic ticket in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, and South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

.Frederickson, 145–147 In other states, they were forced to run as a third-party ticket.

In numbers greater than the 6,000 that attended the first, the States' Rights Democrats held a boisterous second convention in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat of Oklahoma County, it ranks 20th among United States cities in population, and ...

, on August 14, 1948, where they adopted their party platform which stated:

The platform went on to say:

In Arkansas, Democratic gubernatorial nominee Sid McMath

Sidney Sanders McMath (June 14, 1912October 4, 2003) was a U.S. marine, attorney and the 34th governor of Arkansas from 1949 to 1953. In defiance of his state's political establishment, he championed rapid rural electrification, massive highway ...

vigorously supported Truman in speeches across the state, much to the consternation of the sitting governor, Benjamin Travis Laney, an ardent Thurmond supporter. Laney later used McMath's pro-Truman stance against him in the 1950 gubernatorial election, but McMath won re-election handily.

Efforts by States' Rights Democrats to paint other Truman loyalists as turncoats generally failed, although the seeds of discontent were planted which in years to come took their toll on Southern moderates.

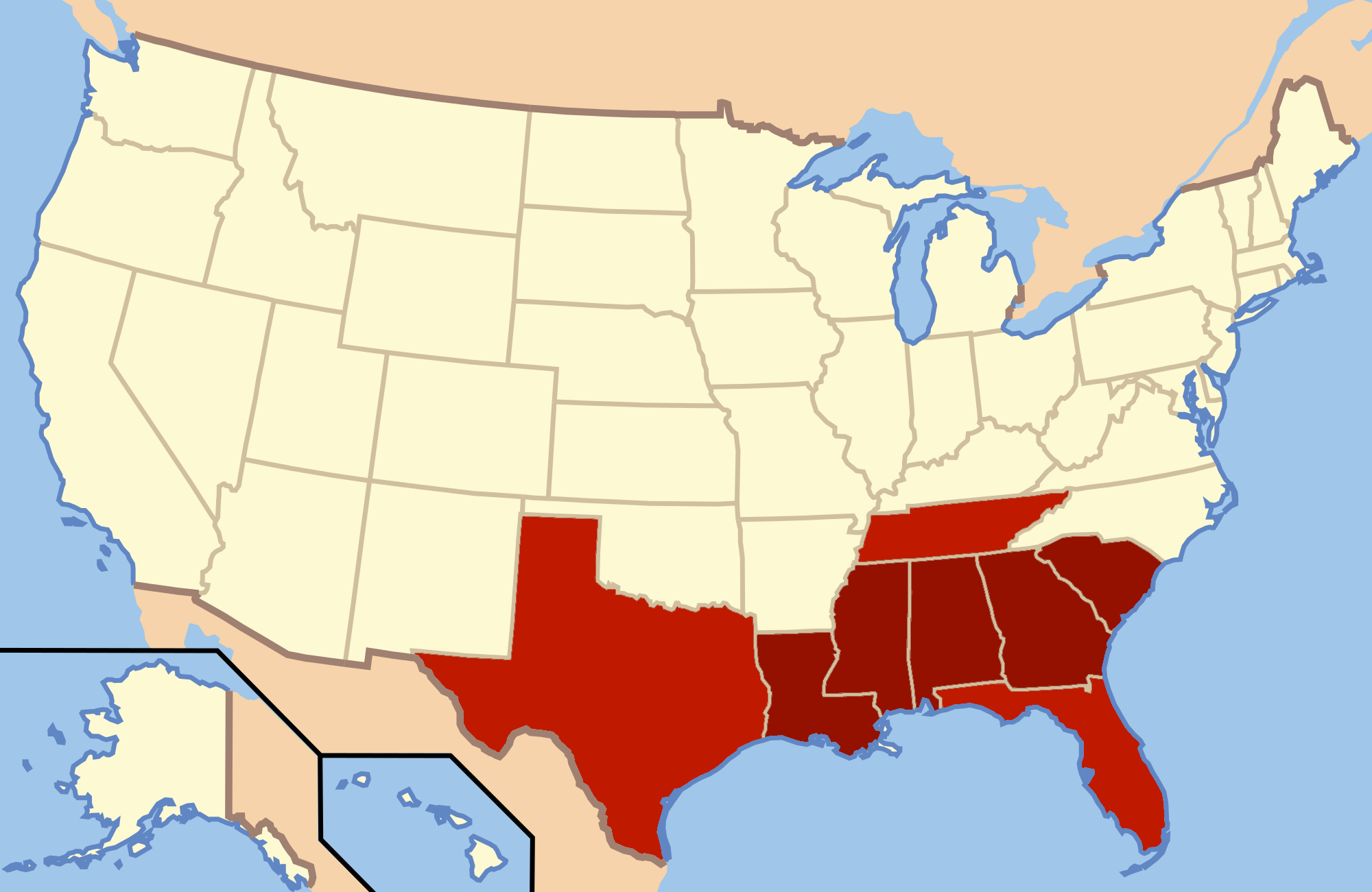

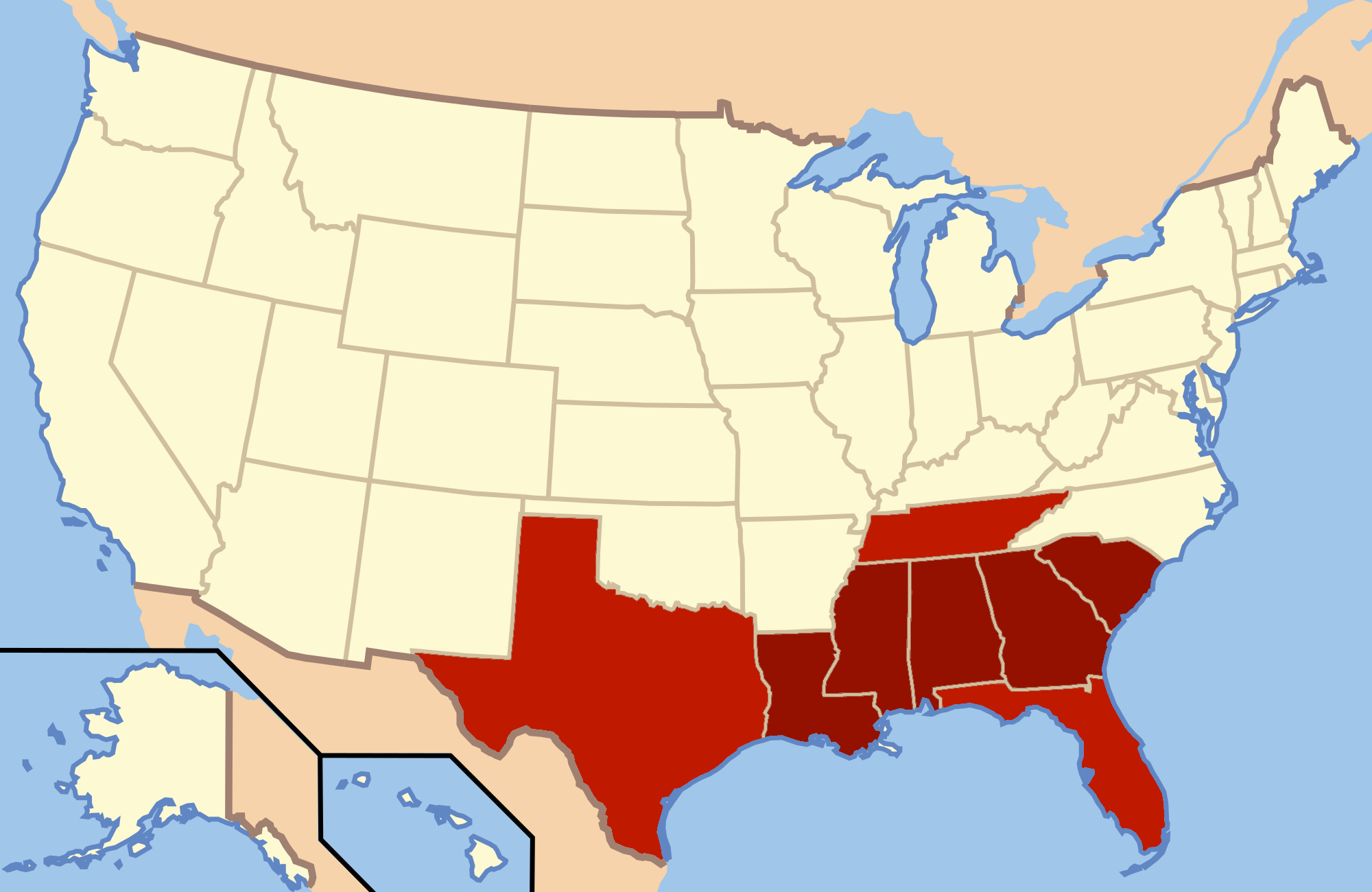

On election day in 1948, the Thurmond–Wright ticket carried the previously solidly Democratic states of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, receiving 1,169,021 popular votes and 39 electoral

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has oper ...

votes. Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

presidential nominee Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

drew off a nearly equal number of popular votes (1,157,172) from the Democrats' left wing, although he did not carry any states. The splits in the Democratic Party in the 1948 election had been expected to produce a victory by GOP presidential nominee Dewey, but Truman defeated Dewey in an upset victory.

Subsequent elections

The States' Rights Democratic Party dissolved after the 1948 election, as Truman, the Democratic National Committee, and the New Deal Southern Democrats acted to ensure that the Dixiecrat movement would not return in the 1952 presidential election. Some Southern diehards, such as Leander Perez of Louisiana, attempted to keep it in existence in their districts. Former Dixiecrats received some backlash at the1952 Democratic National Convention

The 1952 Democratic National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 21 to July 26, 1952, which was the same arena the Republicans had gathered in a few weeks earlier for their national convention f ...

, but all Southern delegations were seated after agreeing to a party loyalty pledge. Moderate Alabama Senator John Sparkman

John Jackson Sparkman (December 20, 1899 – November 16, 1985) was an American jurist and politician from the state of Alabama. A Southern Democrat, Sparkman served in the United States House of Representatives from 1937 to 1946 and the United St ...

was selected as the Democratic vice presidential nominee in 1952, helping to boost party loyalty in the South.

Regardless of the power struggle within the Democratic Party concerning segregation policy, the South remained a strongly Democratic voting bloc for local, state, and federal Congressional elections, but increasingly not in presidential elections. Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower won several Southern states in the 1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Black Saturday in Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, becomes m ...

and 1956 presidential elections. In the 1956 election, former Commissioner of Internal Revenue

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue is the head of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), an agency within the United States Department of the Treasury.

The office of Commissioner was created by Congress as part of the Revenue Act of 1862. Section ...

T. Coleman Andrews

Thomas Coleman Andrews (February 19, 1899 – October 15, 1983) was an American accountant, state and federal government official, and the State's Rights Party candidate for President of the United States in 1956.

Early and family life

Andrew ...

received just under 0.2 percent of the popular vote running as the presidential nominee of the States' Rights Party.1956 Presidential General Election Results/ref> In the 1960 presidential election, Republican

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

won several Southern states, and Senator Harry F. Byrd

Harry Flood Byrd Sr. (June 10, 1887 – October 20, 1966) was an American newspaper publisher, politician, and leader of the Democratic Party in Virginia for four decades as head of a political faction that became known as the Byrd Organization. ...

of Virginia received the votes of several unpledged electors

In United States presidential elections, an unpledged elector is a person nominated to stand as an elector but who has not pledged to support any particular presidential or vice presidential candidate, and is free to vote for any candidate when el ...

from Alabama and Mississippi. In the 1964 presidential election, Republican Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

won all four states that Thurmond had carried in 1948. In the 1968 presidential election, Republican Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

or third party candidate George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist a ...

won every former Confederate state except Texas. Thurmond eventually left the Democratic Party and joined the Republican Party in 1964, charging the Democrats with having "abandoned the people" and having repudiated the U.S. Constitution; he subsequently worked on the presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater.

Presidential candidate performance

See also

*Conservative Democrat

In American politics, a conservative Democrat is a member of the Democratic Party with conservative political views, or with views that are conservative compared to the positions taken by other members of the Democratic Party. Traditionally, c ...

* Boll weevil (politics)

Boll weevils (named for the type of beetle which feeds on cotton buds) was an American political term used in the mid- and late-20th century to describe conservative Democrats.

Background

During and after the administration of Franklin D. R ...

* Politics of the Southern United States

* Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

Footnotes

Further reading

* Bass, Jack, and Marilyn W. Thompson. ''Strom: The Complicated Personal and Political Life of Strom Thurmond'' (2006) * Black, Earl, and Merle Black. ''Politics and Society in the South'' (1989) * Buchanan, Scott. "The Dixiecrat Rebellion: Long-Term Partisan Implications in the Deep South", in ''Politics and Policy'' 33(4):754-769. (2005) * Cohodas, Nadine. ''Strom Thurmond & the Politics of Southern Change'' (1995) * Frederickson, Kari. ''The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968'' (2001) * Karabell, Zachary. ''The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election'' (2001) * Perman, Michael. ''Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South'' (2009)External links

*Scott E. BuchananDixiecrats

''New Georgia Encyclopedia''

1948 Platform of Oklahoma's Dixiecrats

{{Authority control Defunct political parties in the United States History of the Southern United States Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Strom Thurmond Political terminology of the United States Democratic Party (United States) White supremacy in the United States Political parties established in 1948 Political repression in the United States 1948 establishments in the United States Political parties disestablished in 1948 1948 disestablishments in the United States 1948 United States presidential election Politics of the Southern United States Protestant political parties White nationalist parties