Dismemberment on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dismemberment is the act of cutting, ripping, tearing, pulling, wrenching or otherwise disconnecting the limbs from a living or dead being. It has been practiced upon human beings as a form of capital punishment, especially in connection with

Dismemberment is the act of cutting, ripping, tearing, pulling, wrenching or otherwise disconnecting the limbs from a living or dead being. It has been practiced upon human beings as a form of capital punishment, especially in connection with

Queen

Queen

Roman military discipline could be extremely severe, and the emperor

Roman military discipline could be extremely severe, and the emperor

Dismemberment is the act of cutting, ripping, tearing, pulling, wrenching or otherwise disconnecting the limbs from a living or dead being. It has been practiced upon human beings as a form of capital punishment, especially in connection with

Dismemberment is the act of cutting, ripping, tearing, pulling, wrenching or otherwise disconnecting the limbs from a living or dead being. It has been practiced upon human beings as a form of capital punishment, especially in connection with regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

, but can occur as a result of a traumatic accident, or in connection with murder, suicide, or cannibalism. As opposed to surgical

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

amputation

Amputation is the removal of a limb by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on indi ...

of the limbs, dismemberment is often fatal. In criminology

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and s ...

, a distinction is made between offensive dismemberment, in which dismemberment is the primary objective of the dismemberer, and defensive dismemberment, in which the motivation is to destroy evidence.

In 2019, Michael H. Stone, Gary Brucato and Ann Burgess

Ann C. Wolbert Burgess (born October 2, 1936; middle name also spelled Wolpert) is a researcher whose work has focused on developing ways to assess and treat trauma in rape victims. She is a professor at the William F. Connell School of Nursing a ...

proposed formal criteria by which "dismemberment" might be systematically distinguished from the act of "mutilation

Mutilation or maiming (from the Latin: ''mutilus'') refers to Bodily harm, severe damage to the body that has a ruinous effect on an individual's quality of life. It can also refer to alterations that render something inferior, ugly, dysfunction ...

", as these terms are commonly used interchangeably. They suggested that dismemberment involves "the entire removal, by any means, of a large section of the body of a living or dead person, specifically, the head (also termed decapitation

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

), arms, hands, torso, pelvic area, legs, or feet". Mutilation, by contrast, involves "the removal or irreparable disfigurement, by any means, of some smaller portion of one of those larger sections of a living or dead person. The latter would include castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharm ...

(removal of the testes

A testicle or testis (plural testes) is the male reproductive gland or gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testes are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testoste ...

), evisceration

Evisceration (pronunciation: /ɪvɪsəˈreɪʃən/) is disembowelment, i.e., the removal of viscera (internal organs, especially those in the abdominal cavity). The term may also refer to:

* Evisceration (autotomy), ejection of viscera as a defe ...

(removal of the internal organs), and flaying

Flaying, also known colloquially as skinning, is a method of slow and painful execution in which skin is removed from the body. Generally, an attempt is made to keep the removed portion of skin intact.

Scope

A dead animal may be flayed when pr ...

(removal of the skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

)." According to these parameters, removing a whole hand would constitute dismemberment, while removing or damaging a finger would be mutilation; decapitation of a full head would be dismemberment, while removing or damaging a part of the face would be mutilation; and removing a whole torso would be dismemberment, while removing or damaging a breast or the organs contained within the torso would be mutilation.

History

Cutting apart

Slicing to pieces by elephant

Particularly in South-Eastern Asia, execution by trained elephants was a form of capital punishment practiced for several centuries. The techniques by which the convicted person was executed varied widely but did, on occasion, include the elephant dismembering the victim by means of sharp blades attached to its feet. The Muslim travellerIbn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim ...

, visiting Delhi in the 1330s, has left the following eyewitness account of this particular type of execution by elephants:

Quartering procedure in the Holy Roman Empire

In theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

emperor Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

's 1532 Constitutio Criminalis Carolina

The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (sometimes shortened to Carolina) is recognised as the first body of German criminal law (''Strafgesetzbuch''). It was also known as the '' Halsgerichtsordnung'' (Procedure for the judgment of capital crimes) of ...

specifies how ''every'' dismemberment (quartering) should ideally occur:

Thus, the imperially approved way to dismember the convict within the Holy Roman Empire was by means of ''cutting'', rather than dismemberment through ''ripping'' the individual apart. In paragraph 124 of the same code, beheading prior to quartering is mentioned as allowable when extenuating circumstances are present, whereas aggravating circumstances may allow pinching/ripping the criminal with glowing pincers, prior to quartering.

The fate of Wilhelm von Grumbach

Wilhelm von Grumbach (1 June 150318 April 1567) was a German adventurer, chiefly known through his connection with the so-called "Grumbach Feud" (german: Grumbachsche Händel), the last attempt of the Imperial Knights to prevail against the power ...

in 1567, a maverick knight in the Holy Roman Empire who was fond of making his own private wars and was thus condemned for treason, is also worthy of note. Gout-ridden, he was carried to the execution site in a chair and bound fast to a table. The executioner then ripped out his heart, and stuck it in von Grumbach's face with the words: "von Grumbach! Behold your false heart!" Afterwards, the executioner quartered von Grumbach's body. His principal associate was given the same treatment, and an eyewitness stated that ''after'' his heart had been ripped out, Chancellor Brück screamed horribly for "quite some time".

One example of a highly aggravated execution is illustrated by the fate of Bastian Karnhars on 16 July 1600. Karnhars was found guilty of 52 separate acts of murder, including the rape and murder of 8 women, and the murder of a child, whose heart he had allegedly eaten for rituals of black magic. To begin, Karnhars had three strips of flesh torn from his back, before being pinched 18 times with glowing pincers, having his fingers clipped off one by one, his arms and legs broken on the wheel

The breaking wheel or execution wheel, also known as the Wheel of Catherine or simply the Wheel, was a torture method used for public execution primarily in Europe from antiquity through the Middle Ages into the early modern period by breaki ...

, and finally, while still alive, quartered.

Fabled Turkish execution method

In the seventeenth century, a number of travel reports speak of an exotic "Turkish" execution method, where first the waist of a man was constricted by ropes and cords, and then a swift bisection of the trunk was performed. William Lithgow presents a comparatively prosaic description of the method: George Sandys, however, during the same period, tells of a method as no longer in use, in a rather more mythologized way:Shekkeh in Persia

In 1850s Persia, a particular dismemberment technique called ''shekkeh'' is reported to have been used. Travelling as an official for theEast India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

Robert Binning describes it as follows:

Korea

Dismemberment was a form of capital punishment for convicts ofhigh treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

in the Korean kingdom of the Joseon Dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and r ...

. This punishment was, for example, meted out to Hwang Sa-Yong in 1801.

China

The Five Pains is a Chinese variation invented during theQin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

. During the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(AD 618–907), truncation of the body at the waist by means of a fodder knife was a death penalty reserved for those who were seen to have done something particularly treacherous or repugnant. That practice of cutting in two did not originate in the Tang dynasty; in sources concerning the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

(206 BC – AD 220), no fewer than 33 cases of execution by cutting at the waist are mentioned, but occurs very rarely in earlier material.

Current use

Dismemberment is no longer used by most modern governments as a form of execution ortorture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

, though amputation

Amputation is the removal of a limb by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on indi ...

is still carried out in countries that practice Sharia law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

.

Tearing apart

Dismemberment was carried out in theMedieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and Early Modern era and could be effected, for example, by tying a person's limbs to chains or other restraints, then attaching the restraints to separate movable entities (e.g. vehicles) and moving them in opposite directions. Depending on the forces supplied by the horses or other entities, joints of the hips and shoulders were quickly dislocated, but ultimate severing of the tendons and ligaments in order to fully dismember the limbs would sometimes require assistance with cuts from a blade.

By four horses

Also referred to as "disruption" dismemberment could be brought about by chaining four horses to the condemned's arms and legs, thus making them pull him apart, as was the case with the executions of François Ravaillac in 1610,Michał Piekarski

Michał Piekarski (; before 1597 – 27 November 1620), also known as Michael Piekarski, was a Polish petty nobleman and landowner, who attempted to assassinate king Sigismund III in 1620.

Biography

Michał Piekarski, the son of Stanisław, ...

in 1620 and Robert-François Damiens

Robert-François Damiens (; surname also recorded as ''Damier''; 9 January 1715 – 28 March 1757) was a French domestic servant whose attempted assassination of King Louis XV in 1757 culminated in his public execution. He was the last per ...

in 1757. Ravaillac's extended torture and execution has been described like this:

In the case of Damiens, he was condemned to essentially the same fate as Ravaillac, but the execution did not quite work according to plan, as the eyewitness Giacomo Casanova could relate:

As late as in 1781, this gruesome punishment was meted out to the Peruvian

Peruvians ( es, peruanos) are the citizens of Peru. There were Andean and coastal ancient civilizations like Caral, which inhabited what is now Peruvian territory for several millennia before the Spanish conquest of Peru, Spanish conquest in th ...

rebel leader Túpac Amaru II

José Gabriel Condorcanqui ( – May 18, 1781)known as Túpac Amaru II was an indigenous Cacique who led a large Andean rebellion against the Spanish in Peru. He later became a mythical figure in the Peruvian struggle for independence and ...

by the Spanish colonial authorities. The following is an extract from the official judicial death sentence issued by the Spanish authorities which condemns Túpac Amaru II to torture and death. It was ordered in the sentence that Túpac Amaru II be condemned to have his tongue cut out, after watching the executions of his family, and to have his hands and feet tied

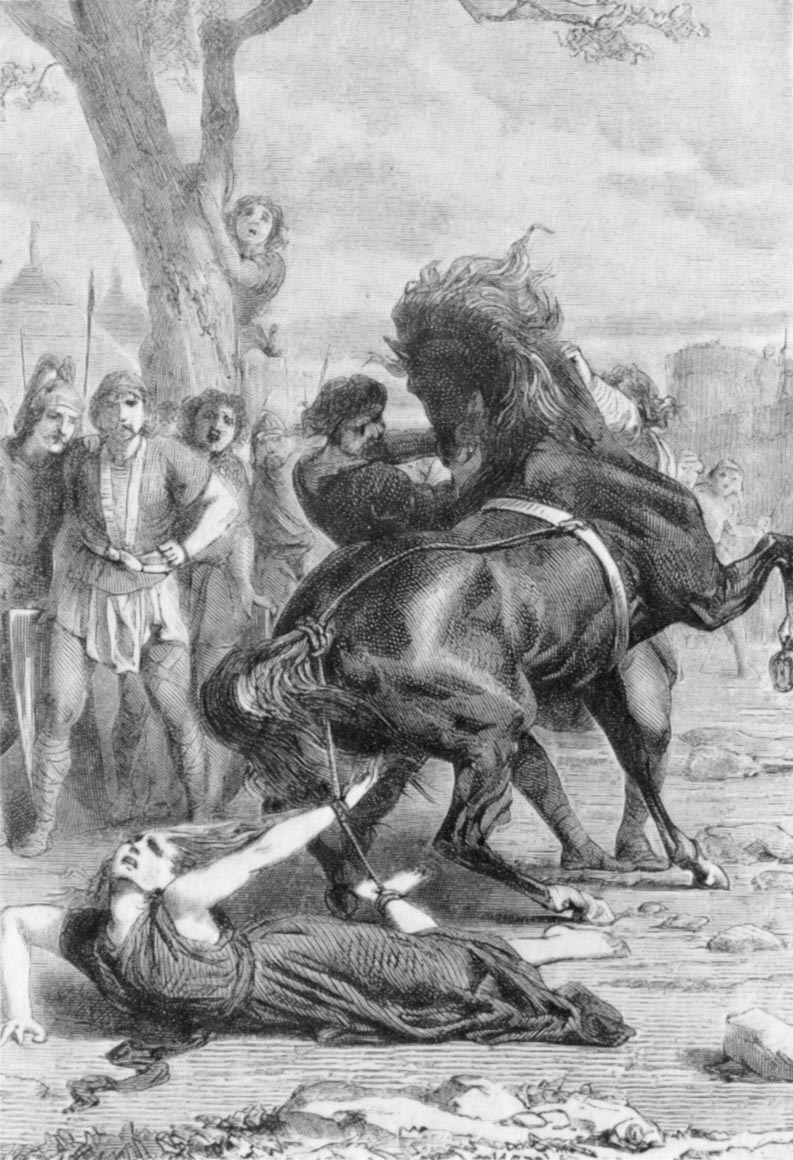

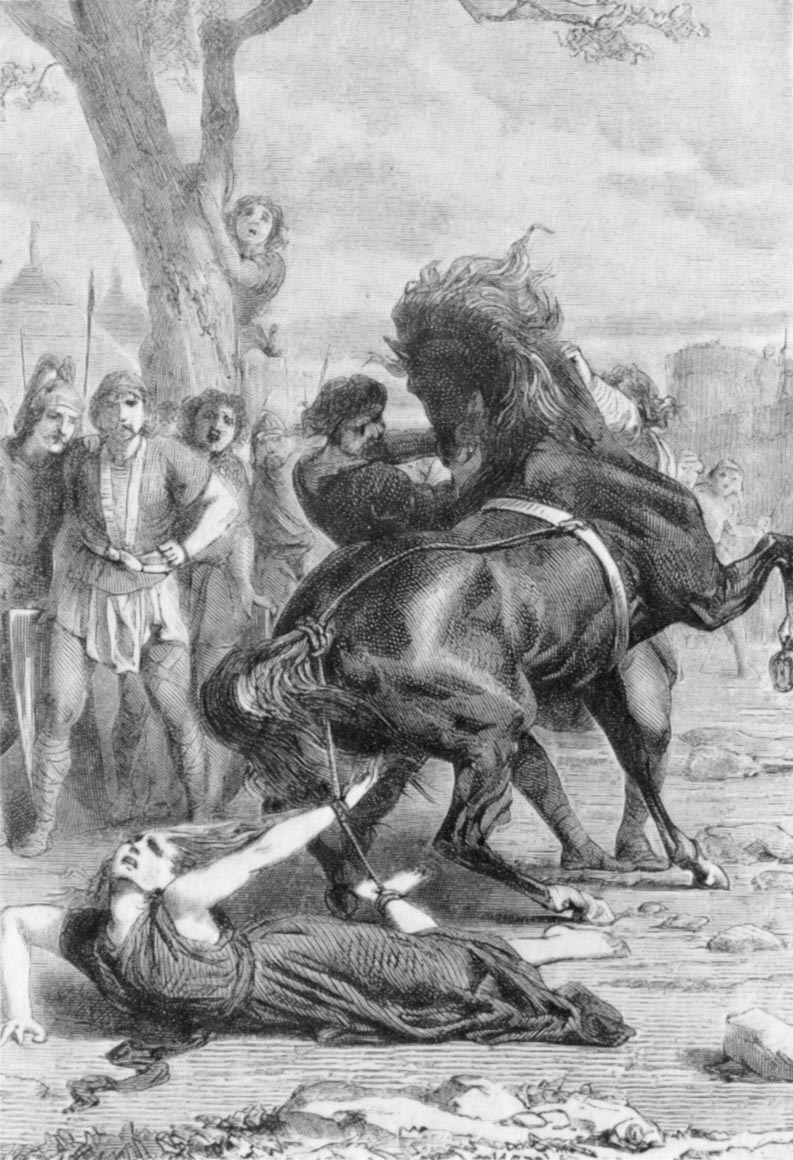

Fate of Queen Brunhilda

Queen

Queen Brunhilda of Austrasia

Brunhilda (c. 543–613) was queen consort of Austrasia, part of Francia, by marriage to the Merovingian king Sigebert I of Austrasia, and regent for her son, grandson and great-grandson.

In her long and complicated career she ruled the eastern ...

, executed in 613, is generally regarded to have suffered the same death, though one account has it that she was tied to the tail of a single horse and thus suffered more of a dragging death

A dragging death is a death caused by someone being dragged behind or underneath a moving vehicle or animal, whether accidental or as a deliberate act of murder.

Instances of dragging death

* Antonio Curcoa (1792)

* James Byrd Jr. (1998)

* Jo ...

. The Liber Historiae Francorum

''Liber Historiae Francorum'' ( en, link=no, "The Book of the History of the Franks") is a chronicle written anonymously during the 8th century. The first sections served as a secondary source for early Franks in the time of Marcomer, giving a ...

, an eighth century chronicle, describes her death by dismemberment as follows:

The story of Brunhilda being tied to the tail of a ''single'' horse (and then to die in some gruesome manner) is promoted, for example, by Ted Byfield (2003), in which he writes: "Then they tied her to the tail of a wild horse; whipped into frenzy, it kicked her to death". The cited source for this claim, however, the seventh century ''Life of St. Columban'' by the monk Jonas, does not support this claim. In paragraph 58 in his work, Jonas just writes: "but Brunhilda he had placed first on a camel in mockery and so exhibited to all her enemies round about then she was bound to the tails of wild horses and thus perished wretchedly".

The storyline of Brunhilde being tied to the tail of a single horse and being subsequently ''dragged'' to death has become a classical motif in artistic representations, as can be seen by the included image.

Torn apart by four ships

According to Olfert Dapper, a 17th-century Dutchman who meticulously collected reports from faraway countries from seamen and other travelers, a fairly frequent maritime death penalty among theBarbary corsairs

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe a ...

was to affix the hands and feet to chains on four different ships. When the ships then sailed off in different directions, the chains grew taut, and the man in between was torn apart after a while.

Torn apart by two trees

Roman military discipline could be extremely severe, and the emperor

Roman military discipline could be extremely severe, and the emperor Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited ...

(r. AD 270–275), who had a reputation for extreme strictness, instituted the rule that soldiers who seduced the wives of their hosts should have their legs fastened to two bent-down trees, which were then released, ripping the man in two. Similarly, in an unsuccessful rebellion against the emperor Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

in AD 366, the usurper Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

met the same fate.

After the defeat of Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dariu ...

by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, the Persian empire was thrown into turmoil, and Darius was killed. One man, Bessus

Bessus or Bessos ( peo, *Bayaçā; grc-gre, Βήσσος), also known by his throne name Artaxerxes V ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης; died summer 329 BC), was a Persian satrap of the eastern Achaemenid sa ...

, claimed the throne as Artaxerxes V, but in 329 BC, Alexander had him executed. The manner of Bessus' death is disputed, and Waldemar Heckel writes:

The method of tying people to bent down trees, which are then allowed to recoil, ripping the individual to pieces in the process is, however, mentioned by several travelers to nineteenth century Persia. The British diplomat James Justinian Morier

James Justinian Morier (15 August 1782 – 19 March 1849) was a British diplomat and author noted for his novels about the Qajar dynasty in Iran, most famously for the ''Hajji Baba'' series. These were filmed in 1954.

Early life

Morier was bor ...

travelled as a special envoy to the Shah in 1808, and Morier writes the following concerning then prevailing criminal justice:

Torn apart by stones

An obscureChristian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

, Severianus was, about the year AD 300, martyred in the following way, according to one tale: One stone was fastened to his head, another bound to his feet. His middle was then fastened by a rope to the top of a wall, and the stones released from the height. His body was ripped apart.

A Christian martyr withstands being torn apart

During the reign of the Roman EmperorDiocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

a Christian named Shamuna was torn apart in the following manner:

Some time thereafter, Shamuna was taken down from his hanging position, and was beheaded instead.

See also

*Breaking wheel

The breaking wheel or execution wheel, also known as the Wheel of Catherine or simply the Wheel, was a torture method used for public execution primarily in Europe from antiquity through the Middle Ages into the early modern period by breakin ...

*Death by sawing

Death by sawing is the act of sawing or cutting a living person in half, either sagittally (usually midsagittally), or transversely. Death by sawing was a method of execution reportedly used in different parts of the world.

Methods

Different me ...

*Decapitation

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

*Hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ...

*Slow slicing

''Lingchi'' (; ), translated variously as the slow process, the lingering death, or slow slicing, and also known as death by a thousand cuts, was a form of torture and execution used in China from roughly 900 CE up until the practice ended aro ...

* Total body disruption

* Waist chop

References

{{Capital punishment Torture Execution methods Amputations