The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member

committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

in the

French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

in the

Coup of 18 Brumaire

The Coup d'état of 18 Brumaire brought Napoleon Bonaparte to power as First Consul of France. In the view of most historians, it ended the French Revolution and led to the Coronation of Napoleon as Emperor. This bloodless ''coup d'état'' ov ...

and replaced by the

Consulate

A consulate is the office of a consul. A type of diplomatic mission, it is usually subordinate to the state's main representation in the capital of that foreign country (host state), usually an embassy (or, only between two Commonwealth co ...

. ''Directoire'' is the name of the final four years of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

. Mainstream historiography also uses the term in reference to the period from the dissolution of the

National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

on 26 October 1795 (4 Brumaire) to Napoleon's coup d’état.

The Directory was continually at war with foreign coalitions, including

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

,

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

,

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was '' de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, the

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

,

Russia and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. It annexed

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to the ...

and the

left bank of the Rhine, while Bonaparte conquered a large part of Italy. The Directory established 196 short-lived sister republics in Italy,

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

and the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Neth ...

. The conquered cities and states were required to send France huge amounts of money, as well as art treasures, which were used to fill the new

Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the '' Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central ...

museum in Paris. An army led by Bonaparte tried to conquer

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medite ...

and marched as far as

Saint-Jean-d'Acre

Acre ( ), known locally as Akko ( he, עַכּוֹ, ''ʻAkō'') or Akka ( ar, عكّا, ''ʻAkkā''), is a city in the coastal plain region of the Northern District of Israel.

The city occupies an important location, sitting in a natural ha ...

in

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. The Directory defeated a resurgence of the

War in the Vendée

The war in the Vendée (french: link=no, Guerre de Vendée) was a counter-revolution from 1793 to 1796 in the Vendée region of France during the French Revolution. The Vendée is a coastal region, located immediately south of the river Loir ...

, the royalist-led civil war in the Vendée region, but failed in its venture to support the

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1798; Ulster-Scots: ''The Hurries'') was a major uprising against British rule in Ireland. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen, a republican revolutionary group influenc ...

and create an Irish Republic.

The French economy was in continual crisis during the Directory. At the beginning, the treasury was empty; the paper money, the

Assignat

An assignat () was a monetary instrument, an order to pay, used during the time of the French Revolution, and the French Revolutionary Wars.

France

Assignats were paper money ( fiat currency) issued by the Constituent Assembly in France from ...

, had fallen to a fraction of its value, and prices soared. The Directory stopped printing assignats and restored the value of the money, but this caused a new crisis; prices and wages fell, and economic activity slowed to a standstill.

In its first two years, the Directory concentrated on ending the excesses of the

Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

; mass executions stopped, and measures taken against exiled priests and royalists were relaxed. The Jacobin political club was closed and the government crushed an armed uprising planned by the Jacobins and an early socialist revolutionary,

François-Noël Babeuf

François-Noël Babeuf (; 23 November 1760 – 27 May 1797), also known as Gracchus Babeuf, was a French proto-communist, revolutionary, and journalist of the French Revolutionary period. His newspaper ''Le tribun du peuple'' (''The Tribune of ...

, known as "''

Gracchus'' Babeuf". But after the discovery of a royalist conspiracy including a prominent general,

Jean-Charles Pichegru

Jean-Charles Pichegru (, 16 February 1761 – 5 April 1804) was a French general of the Revolutionary Wars. Under his command, French troops overran Belgium and the Netherlands before fighting on the Rhine front. His royalist positions led to ...

, the Jacobins took charge of the new Councils and hardened the measures against the Church and émigrés. They took two additional seats in the Directory, hopelessly dividing it.

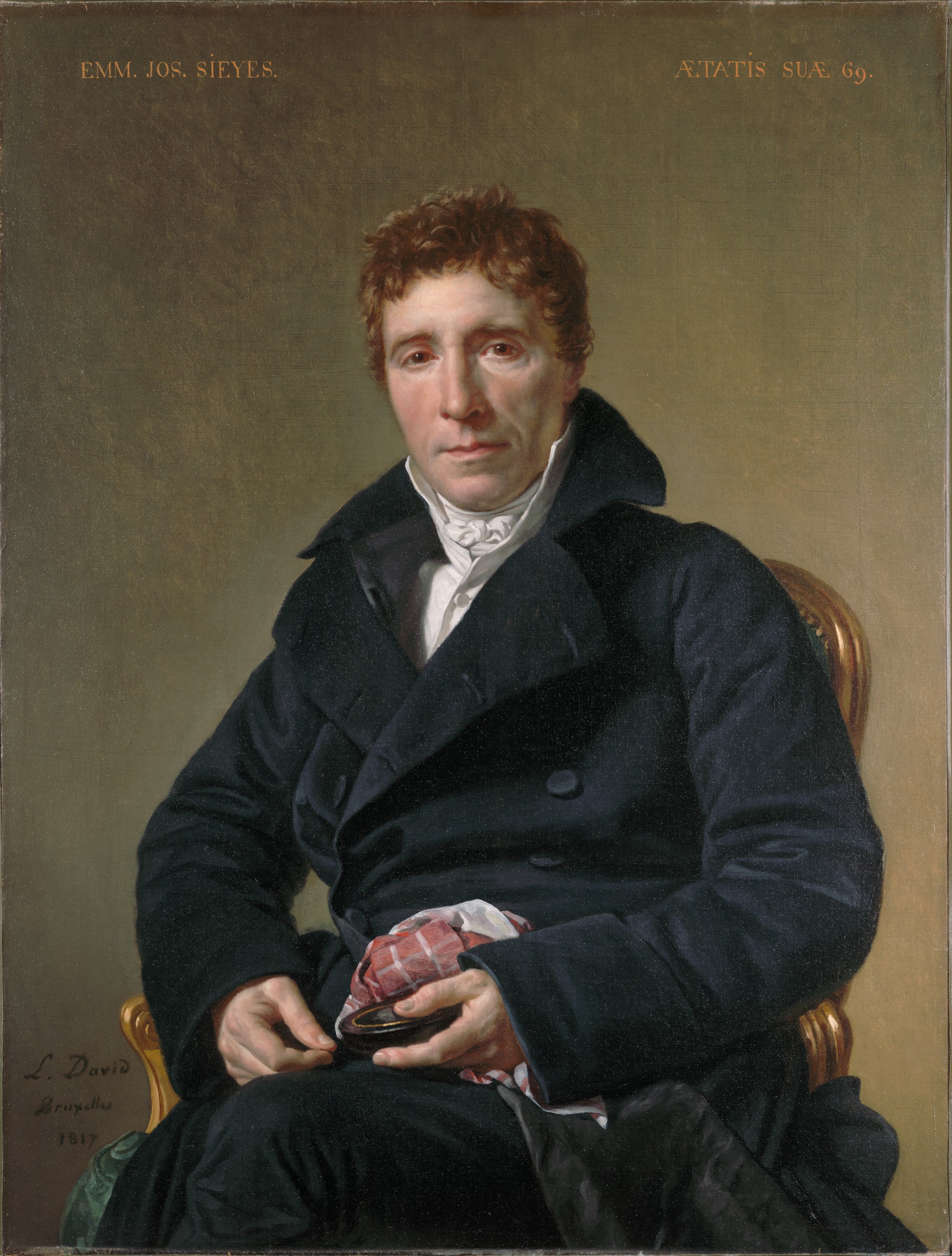

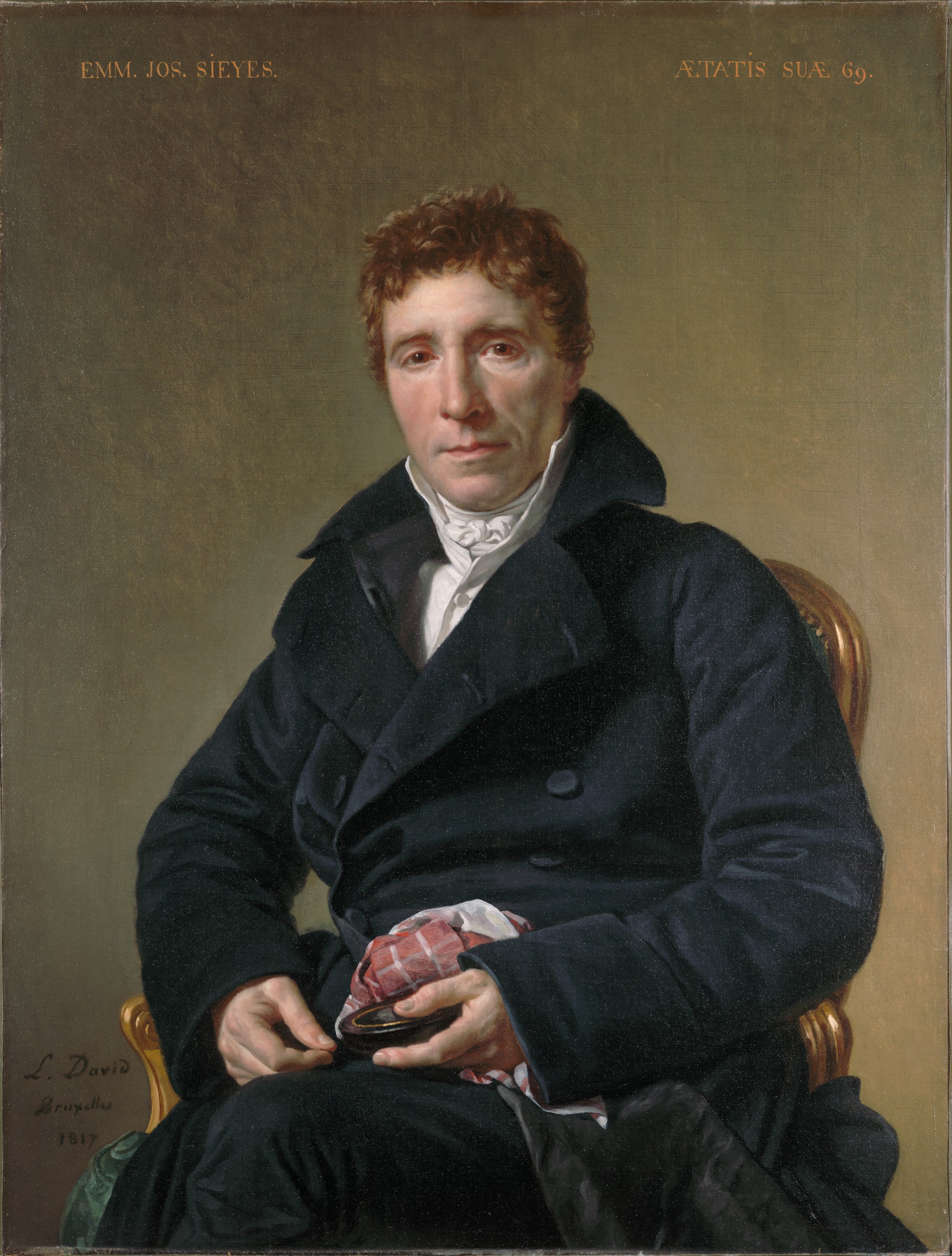

In 1799, after several defeats, French victories in the Netherlands and Switzerland restored the French military position, but the Directory had lost all the political factions' support. Bonaparte returned from Egypt in October, and was engaged by

Abbé Sieyès

''Abbé'' (from Latin ''abbas'', in turn from Greek , ''abbas'', from Aramaic ''abba'', a title of honour, literally meaning "the father, my father", emphatic state of ''abh'', "father") is the French word for an abbot. It is the title for low ...

and others to carry out a parliamentary coup d'état on 8–9 November 1799. The coup abolished the Directory and replaced it with the

French Consulate

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Con ...

led by Bonaparte.

Background

The period known as the

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

began as a way of harnessing revolutionary fervour, but quickly degenerated into the settlement of personal grievances. On 17 September 1793, the

Law of Suspects

:''Note: This decree should not be confused with the Law of General Security (french: Loi de sûreté générale), also known as the "Law of Suspects," adopted by Napoleon III in 1858 that allowed punishment for any prison action, and permitted th ...

authorised the arrest of any suspected "enemies of freedom"; on 10 October, the

National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

recognised the

Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety (french: link=no, Comité de salut public) was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. ...

under

Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

as the

supreme authority, and suspended the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these prin ...

until "peace was achieved".

According to archival records, from September 1793 to July 1794 some 16,600 people were executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activity; another 40,000 may have been summarily executed or died awaiting trial. At its peak, the slightest hint of counter-revolutionary thoughts could place one under suspicion, and even his supporters began to fear their own survival depended on removing Robespierre. On 27 July,

he and his allies were arrested and executed the next day.

In July 1794, the Convention established a committee to draft what became the

1795 Constitution. Largely designed by

Pierre Daunou and

Boissy d'Anglas, it established a

bicameral legislature

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single gro ...

, intended to slow down the legislative process, ending the wild swings of policy under the previous unicameral systems. Deputies were chosen by indirect election, a total franchise of around 5 million voting in primaries for 30,000 electors, or 0.5% of the population. Since they were also subject to stringent property qualification, it guaranteed the return of conservative or moderate deputies.

It created a legislature consisting of the

Council of 500

The Council of Five Hundred (''Conseil des Cinq-Cents''), or simply the Five Hundred, was the lower house of the legislature of France under the Constitution of the Year III. It existed during the period commonly known (from the name of the e ...

, responsible for drafting legislation, and

Council of Ancients, an upper house containing 250 men over the age of 40, who would review and approve it. Executive power was in the hands of five Directors, selected by the Council of Ancients from a list provided by the lower house, with a five-year mandate. This was intended to prevent executive power being concentrated in the hands of one man.

D'Anglas wrote to the Convention:

We propose to you to compose an executive power of five members, renewed with one new member each year, called the Directory. This executive will have a force concentrated enough that it will be swift and firm, but divided enough to make it impossible for any member to even consider becoming a tyrant. A single chief would be dangerous. Each member will preside for three months; he will have during this time the signature and seal of the head of state. By the slow and gradual replacement of members of the Directory, you will preserve the advantages of order and continuity and will have the advantages of unity without the inconveniences.

Drafting the new Constitution

The 1789

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolu ...

was attached as a preamble, declaring "the Rights of Man in society are liberty, equality, security, and property". It guaranteed freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and freedom of labour, but forbade armed assemblies and even public meetings of political societies. Only individuals or public authorities could tender petitions.

The judicial system was reformed, and judges were given short terms of office: two years for justices of the peace, five for judges of department tribunals. They were elected, and could be re-elected, to assure their independence from the other branches of government.

The new legislature had two houses, a

Council of Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred (''Conseil des Cinq-Cents''), or simply the Five Hundred, was the lower house of the legislature of France under the Constitution of the Year III. It existed during the period commonly known (from the name of the ...

and a

Council of Ancients with two hundred fifty members. Electoral assemblies in each

''canton'' of France, which brought together a total of thirty thousand qualified electors, chose representatives to an electoral assembly in each

department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

* Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

, which then elected the members of both houses. The members of this legislature had a term of three years, with one-third of the members renewed every year. The Ancients could not initiate new laws, but could veto those proposed by the Council of Five Hundred.

The Constitution established a unique kind of executive, a five-man Directory chosen by the legislature. It required the Council of Five Hundred to prepare, by secret ballot, a list of candidates for the Directory. The Council of Ancients then chose, again by secret ballot, the Directors from that provided list. The Constitution required that Directors be at least forty years old. To assure gradual but continual change, one Director, chosen by lot, was replaced each year. Ministers for the various departments of State aided the Directors. These ministers did not form a council or cabinet and had no general powers of government.

The new Constitution sought to create a

separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

; the Directors had no voice in legislation or taxation, nor could Directors or Ministers sit in either house. To assure that the Directors would have some independence, each would be elected by one portion of the legislature, and they could not be removed by the legislature unless they violated the law.

[Jean Tulard, Jean-François Fayard, Alfred Fierro, ''Histoire et dictionnaire de la Révolution française'', Robert Laffont, Paris, 1998, pp. 198–199. (In French)]

Under the new

Constitution of 1795, to be eligible to vote in the elections for the Councils, voters were required to meet certain minimum property and residency standards. In towns with over six thousand population, they had to own or rent a property with a revenue equal to the standard income for at least one hundred fifty or two hundred days of work, and to have lived in their residence for at least a year. This ruled out a large part of the French population.

The greatest victim under the new system was the City of Paris, which had dominated events in the first part of the Revolution. On 24 August 1794, the committees of the sections of Paris, bastions of the Jacobins which had provided most of the manpower for demonstrations and invasions of the Convention, were abolished. Shortly afterwards, on 31 August, the municipality of Paris, which had been the domain of Danton and Robespierre, was abolished, and the city placed under direct control of the national government. When the Law of 19 Vendémiaire Year IV (11 October 1795), in application of the

new Constitution, created the first twelve ''

arrondissement

An arrondissement (, , ) is any of various administrative divisions of France, Belgium, Haiti, certain other Francophone countries, as well as the Netherlands.

Europe

France

The 101 French departments are divided into 342 ''arrondissements ...

s'' of Paris, it established twelve new committees, one for each ''arrondissement''. The city became a new

department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

* Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

, the

department of the Seine, replacing the former department of Paris created in 1790.

Political developments (July 1794 – March 1795)

Meanwhile, the leaders of the still ruling

National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

tried to meet challenges from both neo-Jacobins on the left and royalists on the right. On 21 September 1794, the remains of

Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (; born Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the '' sans-culottes'', a radica ...

, whose furious articles had promoted the Reign of Terror, were placed with great ceremony in the

Panthéon

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was ...

, while on the same day, the moderate Convention member

Merlin de Thionville described the Jacobins as "A hangout of outlaws" and the "knights of the guillotine". Young men known as

Muscadins, largely from middle-class families, attacked the Jacobin and radical clubs. The new freedom of the press saw the appearance of a host of new newspapers and pamphlets from the left and the right, such as the royalist ''L'Orateur du peuple'' edited by

Stanislas Fréron, an extreme Jacobin who had moved to the extreme right, and at the opposite end of the spectrum, the ''Tribun du peuple'', edited by

Gracchus Babeuf, a former priest who advocated an early version of

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. On 5 February 1795, the semi-official newspaper ''

Le Moniteur Universel'' (''Le Moniteur'') attacked Marat for encouraging the bloody extremes of the

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

. Marat's remains were removed from the Panthéon two days later. The surviving

Girondin

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnar ...

deputies, whose leaders had been executed during the Reign of Terror, were brought back into the Convention on 8 March 1795.

The Convention tried to bring a peaceful end to the Catholic and royalist

uprising in the Vendée. The Convention signed an amnesty agreement, promising to recognize the freedom of religion and allowing territorial guards to keep their weapons if the ''Vendéens'' would end their revolt. On a proposal from Boissy d'Anglas, on 21 February 1795 the Convention formally proclaimed the freedom of religion and the separation of church and state.

Foreign policy

Between July 1794 and the October 1795 elections for the new-style Parliament, the government tried to obtain international peace treaties and secure French gains. In January 1795 General

Pichegru

Jean-Charles Pichegru (, 16 February 1761 – 5 April 1804) was a French general of the Revolutionary Wars. Under his command, French troops overran Belgium and the Netherlands before fighting on the Rhine front. His royalist positions led to ...

took advantage of an extremely cold winter and invaded the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

. He captured

Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the fourth-largest city and a municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the province of Utrecht. It is located in the eastern corner of the Randstad conurbation, in the very centre of mainland Ne ...

on 18 January, and on 14 February units of French cavalry captured the Dutch fleet, which was trapped in the ice at

Den Helder

Den Helder () is a municipality and a city in the Netherlands, in the province of North Holland. Den Helder occupies the northernmost point of the North Holland peninsula. It is home to the country's main naval base.

From here the Royal TESO f ...

. The Dutch government asked for peace, conceding

Dutch Flanders,

Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of th ...

and

Venlo

Venlo () is a city and municipality in the southeastern Netherlands, close to the border with Germany. It is situated in the province of Limburg, about 50 km east of the city of Eindhoven, 65 km north east of the provincial capital Maastricht, ...

to France. On 9 February, after a French offensive in the Alps, the

Grand Duke of Tuscany

The rulers of Tuscany varied over time, sometimes being margraves, the rulers of handfuls of border counties and sometimes the heads of the most important family of the region.

Margraves of Tuscany, 812–1197 House of Boniface

:These were origin ...

signed a treaty with France. Soon afterwards, on 5 April, France signed a peace treaty, the

Peace of Basel

The Peace of Basel of 1795 consists of three peace treaties involving France during the French Revolution (represented by François de Barthélemy).

*The first was with Prussia (represented by Karl August von Hardenberg) on 5 April;

*The s ...

, with

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was '' de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, where

King Frederick William II was tired of the war; Prussia recognized the French occupation of the western bank of the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, sour ...

. On 22 July 1795, a peace agreement, the "Treaty of Basel", was signed with Spain, where the French army had marched as far as

Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...

. By the time the Directory was chosen, the coalition against France was reduced to Britain and

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

, which hoped that

Russia might be brought in on its side.

Failed Jacobin coup (May 1795) and rebellion in Brittany (June–July)

On 20 May 1795 (1 Prairial Year III), the Jacobins attempted to seize power in Paris. Following the model of Danton's seizure of the National Assembly in June 1792, a mob of

sans-culottes

The (, 'without breeches') were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the . Th ...

invaded the meeting hall of the Convention at the Tuileries, killed one deputy, and demanded that a new government be formed. This time the army moved swiftly to clear the hall. Several deputies who had taken the side of the invaders were arrested. The uprising continued the following day, as the sans-culottes seized the ''

Hôtel de Ville'' as they had done in earlier uprisings, but with little effect; crowds did not move to support them. On the third day, 22 May, the army moved into and occupied the working-class neighborhood of the

Faubourg Saint-Antoine

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine was one of the traditional suburbs of Paris, France.

It grew up to the east of the Bastille around the abbey of Saint-Antoine-des-Champs, and ran along the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine.

Location

The Faubourg Saint-An ...

. The sans-culottes were disarmed and their leaders were arrested. In the following days the surviving members of the Committee of Public Safety, the committee that had been led by Robespierre, were arrested, with the exception of

Carnot and two others. Six of the deputies who had participated in the uprising and had been sentenced to death committed suicide before they were taken to the guillotine.

On 23 June 1795, the

Chouan

Chouan ("the silent one", or "owl") is a French nickname. It was used as a nom de guerre by the Chouan brothers, most notably Jean Cottereau, better known as Jean Chouan, who led a major revolt in Bas-Maine against the French Revolution. Part ...

s, royalist and Catholic rebels in

Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, formed an army of 14,000 men near

Quiberon. With the assistance of the British navy, a force of two thousand royalists was landed at Quiberon. The French army under General

Hoche

Louis Lazare Hoche (; 24 June 1768 – 19 September 1797) was a French military leader of the French Revolutionary Wars. He won a victory over Royalist forces in Brittany. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on ...

reacted swiftly, forcing the royalists to take refuge on the peninsula and then to withdraw. They surrendered on 21 July; 748 of the rebels were executed by firing squad.

Adoption of the new Constitution

The new

Constitution of the Year III was presented to the Convention and debated between 4 July – 17 August 1795, and was formally adopted on 22 August 1795. It was a long document, with 377 articles, compared with 124 in the first French Constitution of 1793. Even before it took effect, however, the members of the Convention took measures to assure they would still have dominance in the legislature over the government. They required that in the first elections, two hundred and fifty new deputies would be elected, while five hundred members of the old Convention would remain in place until the next elections. A national referendum of eligible voters was then held. The total number of voters was low; of five million eligible voters, 1,057,390 electors approved the Constitution, and 49,978 opposed it. The proposal that two thirds of members of the old Convention should remain in place was approved by a much smaller margin, 205,498 to 108,754.

October 1795 royalist rebellion

The new

Constitution of the Year III was officially proclaimed in force on 23 September 1795, but the new Councils had not yet been elected, and the Directors had not yet been chosen. The leaders of the royalists and constitutional monarchists chose this moment to try to seize power. They saw that the vote in favor of the new Constitution was hardly overwhelming. Paris voters were particularly hostile to the idea of keeping two-thirds of the old members of the Convention in the new Councils. A central committee was formed, with members from the wealthier neighborhoods of Paris, and they began planning a march on the center of the city and on the Tuileries, where the Convention still met.

The members of the Convention, very much experienced with conspiracies, were well aware that the planning was underway. A group of five republican deputies, led by

Paul Barras

Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras (, 30 June 1755 – 29 January 1829), commonly known as Paul Barras, was a French politician of the French Revolution, and the main executive leader of the Directory regime of 1795–1799.

Earl ...

, had already formed an unofficial directory, in anticipation of the creation of the real one. They were concerned about the national guard members from western Paris, and were unsure about the military commander of Paris,

General Menou. Barras decided to turn to military commanders in his entourage who were known republicans, particularly

Bonaparte, whom he had known when Bonaparte was successfully fighting the British in Toulon. Bonaparte, at this point a general of second rank in the Army of the Interior, was ordered to defend the government buildings on the right bank.

The armed royalist insurgents planned a march in two columns along both the right bank and left bank of the Seine toward the Tuileries. There on 5 October 1795, the royalists were met by the artillery of ''sous-lieutenant''

Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

at the Sablons and by Bonaparte's soldiers and artillery in front of the church of Saint-Roch. Over the next two hours, the "

whiff of grapeshot" of Bonaparte's cannons and gunfire of his soldiers brutally mowed down advancing columns, killing some four hundred insurgents, and ending the rebellion. Bonaparte was promoted to General of Division on 16 October, and General in Chief of the Army of the Interior on 26 October. It was the last uprising to take place in Paris during the French Revolution.

History

Directory takes charge

Between 12 and 21 October 1795, immediately after the suppression of royalist uprising in Paris, the elections for the new Councils decreed by the new Constitution took place. 379 members of the old Convention, for the most part moderate republicans, were elected to the new legislature. To assure that the Directory did not abandon the Revolution entirely, the Council required that all of the members of the Directory be former members of the Convention and

regicides, those who had voted for the execution of

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was e ...

.

Due to the rules established by the Convention, a majority of members of the new legislature, 381 of 741 deputies, had served in the Convention and were ardent republicans, but a large part of the new deputies elected were royalists, 118 versus 11 from the left. The members of the upper house, the Council of Ancients, were chosen by lot from among all of the deputies.

On 31 October 1795, the Council of Ancients chose the first Directory from a list of candidates submitted by the Council of Five Hundred. One person elected, the

Abbé Sieyès

''Abbé'' (from Latin ''abbas'', in turn from Greek , ''abbas'', from Aramaic ''abba'', a title of honour, literally meaning "the father, my father", emphatic state of ''abh'', "father") is the French word for an abbot. It is the title for low ...

, refused to take the position, saying it didn't suit his interests or personality. A new member,

Lazare Carnot

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, Count Carnot (; 13 May 1753 – 2 August 1823) was a French mathematician, physicist and politician. He was known as the "Organizer of Victory" in the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.

Education and early ...

, was elected in his place.

The members elected to the Directory were the following:

*

Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras

Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras (, 30 June 1755 – 29 January 1829), commonly known as Paul Barras, was a French politician of the French Revolution, and the main executive leader of the Directory regime of 1795–1799.

Early ...

, a member of a minor noble family from

Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

, Barras had been a revolutionary envoy to Toulon, where he met the young Bonaparte, and arranged his promotion to captain. Barras had been removed from the

Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety (french: link=no, Comité de salut public) was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. ...

by Robespierre. Fearing for his life, Barras had helped organize the downfall of Robespierre. An expert at political intrigue, Barras became the dominant figure in the Directory. His leading opponent in the Directory, Carnot, described him as "without faith and without morals... in politics, without character and without resolution... He has all the tastes of an opulent prince, generous, magnificent and dissipated."

*

Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux

Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux (24 August 1753 – 24 March 1824) was a deputy to the National Convention during the French Revolution. He later served as a prominent leader of the French Directory.

Life

He was born at Montaigu (Ve ...

was a fierce republican and anti-Catholic, who had proposed to execute Louis XVI after the

flight to Varennes

The royal Flight to Varennes (french: Fuite à Varennes) during the night of 20–21 June 1791 was a significant event in the French Revolution in which King Louis XVI of France, Queen Marie Antoinette, and their immediate family unsuccessfull ...

. He promoted the establishment of a new religion,

theophilanthropy

The Theophilanthropists ("Friends of God and Man") were a Deistic sect, formed in France during the later part of the French Revolution.

Origins

Thomas Paine, together with other disciples of Rousseau and Robespierre, set up a new religion, in ...

, to replace Christianity.

*

Jean-François Rewbell

Jean-François Reubell or Rewbell (6 October 1747 – 24 November 1807) was a French lawyer, diplomat, and politician of the Revolution.

The revolutionary

Born at Colmar (now in the ''département'' of Haut-Rhin), he became president of the loca ...

had an expertise in foreign relations, and was a close ally of Paul Barras. He was a firm moderate republican who had voted for the death of the King but had also opposed Robespierre and the extreme Jacobins. He was an opponent of the Catholic church and a proponent of individual liberties.

*

Étienne-François Le Tourneur was a former captain of engineers, and a specialist in military and naval affairs. He was a close ally within the Directory of Carnot.

*

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, Count Carnot (; 13 May 1753 – 2 August 1823) was a French mathematician, physicist and politician. He was known as the "Organizer of Victory" in the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.

Education and earl ...

: when the Abbé Sieyés was elected by the Ancients, but refused the position, his place was taken by Carnot. Carnot was an army captain at the beginning of the Revolution, and when elected to the Convention became a member of the commission of military affairs, as well as a vocal opponent of Robespierre. He was an energetic and efficient manager, who restructured the French military and helped it achieve its first successes, earning him the title of "The Organizer of the Victory." Napoleon, who later made Carnot his Minister of War, described him as "a hard worker, sincere in everything, but without intrigues, and easy to fool."

The following day, the members of the new government took over their offices in the

Luxembourg Palace

The Luxembourg Palace (french: Palais du Luxembourg, ) is at 15 Rue de Vaugirard in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. It was originally built (1615–1645) to the designs of the French architect Salomon de Brosse to be the royal residence of the ...

, which had previously been occupied by the Committee of Public Safety. Nothing had been prepared, and the rooms had no furniture: they managed to find firewood to heat the room, and a table in order to work. Each member took charge of a particular sector: Rewbell diplomacy; Carnot and Le Tourneur military affairs, La Révellière-Lépeaux religion and public instruction, and Barras internal affairs.

The Council of Ancients was attributed the building at the Tuileries Palace formerly occupied by the Convention, while the Council of Five Hundred deliberated in the ''

Salle du Manège

The indoor riding academy called the ''Salle du Manège'' () was the seat of deliberations during most of the French Revolution, from 1789 to 1798. It was demolished in 1804 to make way for the rue de Rivoli.

History

Before the Revolution ...

'', the former riding school west of the palace in the

Tuileries Garden

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palac ...

. One of the early decisions of the new parliament was to designate uniforms for both houses: the Five Hundred wore long white robes with a blue belt, a scarlet cloak and a hat of blue velour, while members of the Ancients wore a robe of blue-violet, a scarlet sash, a white mantle, and a violet hat.

Gallery

File:Paul Barras.jpg, Paul Barras

Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras (, 30 June 1755 – 29 January 1829), commonly known as Paul Barras, was a French politician of the French Revolution, and the main executive leader of the Directory regime of 1795–1799.

Earl ...

(here in the ceremonial dress of a Director) was a master of political intrigue

File:La Révellière-Lépeaux Directeur.JPG, Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux

Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux (24 August 1753 – 24 March 1824) was a deputy to the National Convention during the French Revolution. He later served as a prominent leader of the French Directory.

Life

He was born at Montaigu (Ve ...

File:Jean-François Reubell.JPG, Jean-François Rewbell

Jean-François Reubell or Rewbell (6 October 1747 – 24 November 1807) was a French lawyer, diplomat, and politician of the Revolution.

The revolutionary

Born at Colmar (now in the ''département'' of Haut-Rhin), he became president of the loca ...

File:Étienne-François Le Tourneur - Directeur.jpg, Étienne-François Le Tourneur

File:Portrait Lazare Carnot.jpg, Lazare Carnot

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, Count Carnot (; 13 May 1753 – 2 August 1823) was a French mathematician, physicist and politician. He was known as the "Organizer of Victory" in the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.

Education and early ...

, a brilliant organizer and mathematician but poor intriguer, was the enemy of Barras

Finance and economy

The new Director overseeing financial affairs, La Réveillière-Lépeaux, gave a succinct description of the financial state of France when the Directory took power: "The national Treasury was completely empty; not a single sou remained. The

assignats

An assignat () was a monetary instrument, an order to pay, used during the time of the French Revolution, and the French Revolutionary Wars.

France

Assignats were paper money (fiat currency) issued by the Constituent Assembly in France from ...

were almost worthless; the little value which remained drained away each day with accelerated speed. One could not print enough money in one night to meet the most pressing needs of the next day.... The public revenues were nonexistent; citizens had lost the habit of paying taxes.

..All public credit was dead and all confidence lost.

..The depreciation of the ''assignats'', the frightening speed of the fall, reduced the salary of all public employees and functionaries to a value which was purely nominal."

The drop in value in the money was accompanied by extraordinary inflation. The ''

Louis d'or

The Louis d'or () is any number of French coins first introduced by Louis XIII in 1640. The name derives from the depiction of the portrait of King Louis on one side of the coin; the French royal coat of arms is on the reverse. The coin was re ...

'' (gold coin), which was worth 2,000

₶. in paper money at the beginning of the Directory, increased to 3,000₶. and then 5,000₶. The price of a liter of wine increased from 2₶.10

s. in October 1795 to 10₶. and then 30₶. A measure of flour worth 2₶. in 1790 was worth 225₶. in October 1794.

The new government continued to print ''assignats'', which were based on the value of property confiscated from the Church and the aristocracy, but it could not print them fast enough; even when it printed one hundred million in a day, it covered only one-third of the government's needs. To fill the treasury, the Directory resorted in December 1795 to a forced loan of 600 million-₶. from wealthy citizens, who were required to pay between 50₶. and 6,000₶. each.

To fight inflation, the government began minting more coins of gold and silver, which had real value; the government had little gold but large silver reserves, largely in the form of silverware, candlesticks and other objects confiscated from the churches and the nobility. It minted 72 million

écus, and when this silver supply ran low, it obtained much more gold and silver through military campaigns outside of France, particularly from Bonaparte's

army in Italy. Bonaparte demanded gold or silver from each city he conquered, threatening to destroy the cities if they did not pay.

These measures reduced the rate of inflation. On 19 February 1796, the government held a ceremony in the

Place Vendôme

The Place Vendôme (), earlier known as Place Louis-le-Grand, and also as Place Internationale, is a square in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France, located to the north of the Tuileries Gardens and east of the Église de la Madeleine. It i ...

to destroy the printing presses which had been used to produce huge quantities of ''assignats''. This success produced a new problem: the country was still flooded with more than two billion four hundred million (2.400.000.000) ''assignats'', claims on confiscated properties, which now had some value. Those who held ''assignats'' were able to exchange them for state mandates, which they could use to buy châteaux, church buildings and other

biens nationaux

The biens nationaux were properties confiscated during the French Revolution from the Catholic Church, the monarchy, émigrés, and suspected counter-revolutionaries for "the good of the nation".

''Biens'' means "goods", both in the sense of " ...

(state property) at extremely reduced prices. Speculation became rampant, and property in Paris and other cities could change hands several times a day.

Another major problem faced by the Directory was the enormous public debt, the same problem that had led to the Revolution in the first place. In September–December 1797, the Directory attacked this problem by declaring bankruptcy on two-thirds of the debt, but assured payment on the other third. This resulted in the ruin of those who held large quantities of government bonds, but stabilized the currency. To keep the treasury full, the Directory also imposed new taxes on property owners, based on the number of fireplaces and chimneys, and later on the number of windows, of their residences. It refrained from adding more taxes on wine and salt, which had helped cause the 1789 revolution, but added new taxes on gold and silver objects, playing cards, tobacco, and other luxury products. Through these means, the Directory brought about a relative stability of finances which continued through the Directory and Consulate.

Food supply

The food supply for the population, and particularly for the Parisians, was a major economic and political problem before and during the Revolution; it had led to food riots in Paris and attacks on the

Convention. To assure the supply of food to the

sans-culottes

The (, 'without breeches') were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the . Th ...

in Paris, the base of support of the

Jacobins

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

, the Convention had strictly regulated grain distribution and set maximum prices for bread and other essential products. As the value of the currency dropped, the fixed prices soon did not cover the cost of production, and supplies dropped. The Convention was forced to abolish the

maximum

In mathematical analysis, the maxima and minima (the respective plurals of maximum and minimum) of a function, known collectively as extrema (the plural of extremum), are the largest and smallest value of the function, either within a given ran ...

on 24 December 1794, but it continued to buy huge quantities of bread and meat which it distributed at low prices to the Parisians. This Paris food distribution cost a large part of the national budget, and was resented by the rest of the country, which did not have that benefit. By early 1796, the grain supply was supplemented by deliveries from

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and even from

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. Despite the increased imports, the grain supply to Paris was not enough. The Ministry of the Interior reported on 23 March 1796 that there was only enough wheat to make bread for five days, and there were shortages of meat and firewood. The Directory was forced to resume deliveries of subsidized food to the very poor, the elderly, the sick, and government employees. The food shortages and high prices were one factor in the growth of discontent and the

Gracchus Babeuf's uprising, the

Conspiracy of the Equals, in 1796. The harvests were good in the following years and the food supplies improved considerably, but the supply was still precarious in the north, the west, the southeast, and the valley of the Seine.

Babeuf's Conspiracy of the Equals

In 1795, the Directory faced a new threat from the left, from the followers of

François Noël Babeuf, a talented political agitator who took the name ''Gracchus'' and was the organizer of what became known as the

Conspiracy of the Equals. Babeuf had, since 1789, been drawn to the Agrarian Law, an agrarian reform preconized by the ancient Roman brothers,

Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, of sharing

goods in common, as means of achieving economic equality. By the time of the

fall of Robespierre, he had abandoned this as an impractical scheme and was moving towards a more complex plan. Babeuf did not call for the abolition of private property, and wrote that peasants should own their own plots of land, but he advocated that all wealth should be shared equally: all citizens who were able would be required to work, and all would receive the same income. Babeuf did not believe that the mass of French citizens was ready for self-government; accordingly, he proposed a dictatorship under his leadership until the people were educated enough to take charge. "People!", Babeuf wrote. "Breathe, see, recognize your guide, your defender.... Your tribune presents himself with confidence."

At first, Babeuf's following was small; the readers of his newspaper, ''Le Tribun du peuple'' ("The Tribune of the People"), were mostly middle-class far-left Jacobins who had been excluded from the new government. However, his popularity increased in the working-class of the capital with the drop in value of the ''assignats'', which rapidly resulted in the decrease of wages and the rise of food prices. Beginning in October 1795, he allied himself with the most radical Jacobins, and on 29 March 1796 formed the ''Directoire secret des Égaux'' ("Secret Directory of Equals"), which proposed to "revolutionize the people" through pamphlets and placards, and eventually to overthrow the government. He formed an alliance of utopian socialists and radical Jacobins, including

Félix Lepeletier

Felix may refer to:

* Felix (name), people and fictional characters with the name

Places

* Arabia Felix is the ancient Latin name of Yemen

* Felix, Spain, a municipality of the province Almería, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, ...

,

Pierre-Antoine Antonelle,

Sylvain Marechal,

Jean-Pierre-André Amar and

Jean-Baptiste Robert Lindet. The

Conspiracy of Equals was organized in a novel way: in the center was Babeuf and the Secret Directory, who hid their identities, and shared information with other members of the Conspiracy only via trusted intermediaries. This conspiratorial structure was later adopted by Marxist movements. Despite his precautions, the Directory infiltrated an agent into the conspiracy, and was fully informed of what he was doing. Bonaparte, the newly named commander of the

Army of the Interior, was ordered to close the

Panthéon Club

, named_after = Panthéon

, motto =

, predecessor = Jacobin Club

, merged =

, formation = 6 November 1795

, dissolved = 27 February 1796

, merger =

, type ...

, the major meeting place for the Jacobins in Paris, which he did on 27 February 1796. The Directory took other measures to prevent an uprising; the Legion of Police (''légion de police''), a local police force dominated by Jacobins, was forced to become a part of the Army, and the Army organized a mobile column to patrol the neighborhoods and stop uprisings.

Before Babeuf and his conspiracy could strike, he was betrayed by a police spy and arrested in his hiding place on 10 May 1796. Though he was a talented agitator, he was a very poor conspirator; with him in his hiding place were the complete records of the conspiracy, with all of the names of the conspirators. Despite this setback, the conspiracy went ahead with its plans. On the night of 9–10 September 1796, between 400 and 700 Jacobins went to the 21st Regiment of Dragoons (''21e régiment de dragons'') army camp at

Grenelle

Grenelle () is a neighbourhood in southwestern Paris, France. It is a part of the 15th arrondissement of the city.

There is currently a Boulevard de Grenelle which runs along the North delimitation of the ''quartier'', and a Rue de Grenelle, ...

and tried to incite an armed rebellion against the Convention. At the same time a column of militants was formed in the working-class neighborhoods of Paris to march on the Luxembourg Palace, headquarters of the Directory. Director Carnot had been informed the night before by the commander of the camp, and a unit of dragoons was ready. When the attack began at about ten o'clock, the dragoons appeared suddenly and charged. About twenty Jacobins were killed, and the others arrested. The column of militants, learning what had happened, disbanded in confusion. The widespread arrest of Babeuf's militants and Jacobins followed. The practice of arresting suspects at their homes at night, stopped after the downfall of Robespierre, was resumed on this occasion.

Despite his arrest, Babeuf, in jail, still felt he could negotiate with the government. He wrote to the Directory: "Citizen Directors, why don't you look above yourselves and treat with me as with an equal power? You have seen now the vast confidence of which I am the center... this view makes you tremble." Several attempts were made by Babeuf's followers to free him from prison. He was finally moved to

Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a subprefecture of the department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the main towns along the river Loir. The river divides itself at the ...

for trial. The Directory did not tremble. The accused Jacobins were tried by military courts between 19 September and 27 October. Thirty Jacobins, including three former deputies of the Convention, were convicted and guillotined. Babeuf and his principal followers were tried in Vendôme between 20 February and 26 May 1797. The two principal leaders, Babeuf and

Darthé, were convicted. They both attempted suicide, but failed and were guillotined on 27 May 1797. However, in the following months, the Directory and Councils gradually turned away from the royalist right and tried to find new allies on the left.

War and Diplomacy (1796–1797)

The major preoccupation of the Directory during its existence was the war against the coalition of

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

. The military objective set by the Convention in October 1795 was to enlarge France to what were declared its natural limits: the

Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

, the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, sour ...

and the

Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

, the borders of

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the Eas ...

at the time of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medit ...

. In 1795,

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was '' de facto'' dissolved by an ...

,

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

quit

the War of the First Coalition and made peace with France, but Great Britain refused to accept the French annexation of

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to the ...

. Beside Britain and Austria, the only enemies remaining for France were the kingdom of

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian language, Italian, Corsican language, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese dialect, Algherese and Catalan languag ...

and several small Italian states. Austria proposed a European congress to settle borders, but the Directory refused, demanding direct negotiations with Austria instead. Under British pressure, Austria agreed to continue the war against France.

Lazare Carnot

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, Count Carnot (; 13 May 1753 – 2 August 1823) was a French mathematician, physicist and politician. He was known as the "Organizer of Victory" in the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.

Education and early ...

, the Director who oversaw military affairs, planned a new campaign against Austria, using three armies: General

Jourdan's Army of Sambre-et-Meuse

The Army of Sambre and Meuse (french: Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse) was one of the armies of the French Revolution. It was formed on 29 June 1794 by combining the Army of the Ardennes, the left wing of the Army of the Moselle and the right win ...

on the Rhine and General

Moreau's

Army of the Rhine and Moselle on the Danube would march to

Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and dictate a peace. A third army, the

Army of Italy under General Bonaparte, who had risen in rank with spectacular speed due to his defense of the government from a royalist uprising, would carry out a diversionary operation against Austria in northern Italy. Jourdan's army captured

Mayence and

Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian dialects, Hessian: , "Franks, Frank ford (crossing), ford on the Main (river), Main"), is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as o ...

, but on 14 August 1796 was defeated by the Austrians at the

Battle of Amberg

The Battle of Amberg, fought on 24 August 1796, resulted in an Habsburg victory by Archduke Charles over a French army led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. This engagement marked a turning point in the Rhine campaign, which had previously seen Fre ...

and again on 3 September 1796 at the

Battle of Würzburg

The Battle of Würzburg was fought on 3 September 1796 between an army of the Habsburg monarchy led by Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen and an army of the First French Republic led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. The French attacked the archduke' ...

, and had to retreat back to the Rhine. General Moreau, without the support of Jourdan, was also forced to retreat.

Italian campaign

The story was very different in Italy. Bonaparte, though he was only twenty-eight years old, was named commander of the Army of Italy on 2 March 1796, through the influence of Barras, his patron in the Directory. Bonaparte faced the combined armies of Austria and Sardinia, which numbered seventy thousand men. Bonaparte slipped his army between them and defeated them in a series of battles, culminating at the

Battle of Mondovi where he defeated the Sardinians on 22 April 1796, and the

Battle of Lodi

The Battle of Lodi was fought on 10 May 1796 between French forces under Napoleon Bonaparte and an Austrian rear guard led by Karl Philipp Sebottendorf at Lodi, Lombardy. The rear guard was defeated, but the main body of Johann Peter Beauli ...

, where he defeated the Austrians on 10 May. The

king of Sardinia and Savoy was forced to make peace in May 1796 and ceded

Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

and

Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Sa ...

to France.

At the end of 1796, Austria sent two new armies to Italy to expel Bonaparte, but Bonaparte outmaneuvered them both, winning a first victory at the

Battle of Arcole

The Battle of Arcole or Battle of Arcola (15–17 November 1796) was fought between French and Austrian forces southeast of Verona during the War of the First Coalition, a part of the French Revolutionary Wars. The battle saw a bold maneuver ...

on 17 November 1796, then at the

Battle of Rivoli

The Battle of Rivoli (14–15 January 1797) was a key victory in the French campaign in Italy against Austria. Napoleon Bonaparte's 23,000 Frenchmen defeated an attack of 28,000 Austrians under General of the Artillery Jozsef Alvinczi, e ...

on 14 January 1797. He forced Austria to sign the

Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The treaty ...

(October 1797), whereby

the emperor ceded

Lombardy

(man), (woman) lmo, lumbard, links=no (man), (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, ...

and the

Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The p ...

to the French Republic in exchange for

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isl ...

and urged

the Diet to surrender the lands beyond the Rhine.

[Black, p. 173.]

Spanish alliance

The Directory was eager to form a coalition with Spain to block British commerce with the continent and to close the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

to British ships. By the

Treaty of San Ildefonso, concluded in August 1796, Spain became the ally of France, and on 5 October, it declared war on Britain. The British fleet under Admiral

Jervis defeated the Spanish fleet at the

Cape St Vincent, keeping the Mediterranean open to British ships, but the United Kingdom was brought into such extreme peril by the mutinies in its fleet that it offered to acknowledge the French conquest of the Netherlands and to restore the French colonies.

Irish Misadventure

The Directory also sought a new way to strike British interests and to repay the 1707–1800

Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, wh ...

for the support it gave to royalist insurgents in

Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. A French fleet of 44 vessels departed

Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

** Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

* B ...

on 15 December 1796, carrying an expeditionary force of 14,000 soldiers, led by General Hoche to

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, where they hoped to join forces with Irish rebels to expel the British from the 1542–1800

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label= Classical Irish, an Ríoghacht Éireann; ga, label= Modern Irish, an Ríocht Éireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed fr ...

. However, the fleet was separated by storms off the Irish coast and, being unable to land on Ireland, had to return to home port with 31 vessels and 12,000 surviving soldiers.

Rise of the royalists and coup d'état (1797)

The first elections held after the formation of the Directory were held in March and April 1797, in order to replace one-third of the members of the Councils. The elections were a crushing defeat for the old members of the Convention; 205 of the 216 were defeated. Only eleven former deputies from the Convention were reelected, several of whom were royalists. The elections were a triumph for the royalists, particularly in the south and in the west; after the elections there were about 160 royalist deputies, divided between those who favored a return to an absolute monarchy, and those who wished a constitutional monarchy on the British model. The constitutional monarchists elected to the Council included

Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours

Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours ( or ; ; 14 December 1739 – 7 August 1817) was a French-American writer, economist, publisher and government official. During the French Revolution, he, his two sons and their families immigrated to the Un ...

, who later emigrated to the United States with his family, and whose son,

Éleuthère Irénée du Pont, founded the "E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company", now known as

DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

. In Paris and other large cities, the candidates of the left dominated. General

Jean-Charles Pichegru

Jean-Charles Pichegru (, 16 February 1761 – 5 April 1804) was a French general of the Revolutionary Wars. Under his command, French troops overran Belgium and the Netherlands before fighting on the Rhine front. His royalist positions led to ...

, a former Jacobin and ordinary soldier who had become one of the most successful generals of the Revolution, was elected president of the new Council of Five Hundred.

François Barbé-Marbois, a diplomat and future negotiator of the sale of

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

to the United States, was elected president of the Council of Ancients.

Royalism was not strictly legal, and deputies could not announce themselves as such, but royalist newspapers and pamphlets soon appeared, there were pro-monarchy demonstrations in theaters, and royalists wore identifying clothing items, such as black velvet collars, in show of mourning for the execution of Louis XVI. The parliamentary royalists demanded changes in the government fiscal policies, and a more tolerant position toward religion. During the Convention, churches had been closed and priests required to take an

oath to the government. Priests who had refused to take the oath were expelled from the country, on pain of the death penalty if they returned. Under the Directory, many priests had quietly returned, and many churches around the country had re-opened and were discreetly holding services. When the Directory proposed moving the ashes of the celebrated mathematician and philosopher

René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Math ...

to the ''

Panthéon

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was ...

'', one deputy,

Louis-Sébastien Mercier

Louis-Sébastien Mercier (6 June 1740 – 25 April 1814) was a French dramatist and writer, whose 1771 novel ''L'An 2440'' is an example of proto-science fiction.

Early life and education

He was born in Paris to a humble family: his father was a ...

, a former

Girondin

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnar ...

and opponent of the Jacobins, protested that the ideas of Descartes had inspired the

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

of the Revolution and destroyed religion in France. Descartes' ashes were not moved. ''Émigrés'' who had left during the Revolution had been threatened by the Convention with the death penalty if they returned; now, under the Directory, they quietly began to return.

Parallel with the parliamentary royalists, but not directly connected with them, a clandestine network of royalists existed, whose objective was to place

Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

, then in exile in

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, on the French throne. They were funded largely by Britain, through the offices of

William Wickham, the British spymaster who had his headquarters in

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

. These networks were too divided and too closely watched by the police to have much effect on politics. However, Wickham did make one contact that proved to have a decisive effect on French politics: through an intermediary, he had held negotiations with General Pichegru, then commander of the Army of the Rhine.

The Directory itself was divided.

Carnot,

Letourneur and

La Révellière Lépeaux were not royalists, but favored a more moderate government, more tolerant of religion. Though Carnot himself had been a member of the

Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety (french: link=no, Comité de salut public) was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. ...

led by Robespierre, he declared that the Jacobins were ungovernable, that the Revolution could not go on forever, and that it was time to end it. A new member,

François-Marie, marquis de Barthélemy