Diadochi wars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Wars of the Diadochi ( grc, Πόλεμοι τῶν Διαδόχων, '), or Wars of Alexander's Successors, were a series of conflicts that were fought between the generals of

Perdiccas, who was already betrothed to the daughter of Antipater, attempted to marry Alexander's sister, Cleopatra, a marriage which would have given him claim to the Macedonian throne. In 322 BC, Antipater, Craterus and Antigonus all formed a coalition against Perdiccas's growing power. Soon after, Antipater would send his army, under the command of Craterus, into Asia Minor. In late 322 or early 321 BC,

Perdiccas, who was already betrothed to the daughter of Antipater, attempted to marry Alexander's sister, Cleopatra, a marriage which would have given him claim to the Macedonian throne. In 322 BC, Antipater, Craterus and Antigonus all formed a coalition against Perdiccas's growing power. Soon after, Antipater would send his army, under the command of Craterus, into Asia Minor. In late 322 or early 321 BC,

Alexander's successors: the Diadochi

from Livius.org (Jona Lendering)

Wiki Classical Dictionary: "Successors" category

an

Diadochi entry

T. Boiy, "Dating Methods During the Early Hellenistic Period", ''Journal of Cuneiform Studies'', Vol. 52, 2000

''PDF format''. A recent study of primary sources for the chronology of eastern rulers during the period of the Diadochi. {{Authority control Macedonian Empire 4th century BC in Macedonia (ancient kingdom) 3rd century BC in Macedonia (ancient kingdom) 290s BC conflicts 280s BC conflicts 270s BC conflicts Wars involving Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, known as the Diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

, over who would rule his empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

following his death. The fighting occurred between 322 and 281 BC.

Background

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

died on June 10, 323 BC, leaving behind an empire that stretched from Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled ...

and the rest of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

to the Indus valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

. The empire had no clear successor, with the Argead family, at this point, consisting of Alexander's mentally disabled half-brother, Arrhidaeus

Arrhidaeus or Arrhidaios ( el, Ἀρριδαῖoς lived 4th century BC), one of Alexander the Great's generals, was entrusted by Ptolemy to bring Alexander's body to Egypt in 323 BC, contrary to the wishes of Perdiccas who wanted the body sent t ...

; his unborn son Alexander IV; his reputed illegitimate son Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptiv ...

; his mother Olympias

Olympias ( grc-gre, Ὀλυμπιάς; c. 375–316 BC) was a Greek princess of the Molossians, and the eldest daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip II, the king of Macedoni ...

; his sister Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

; and his half-sisters Thessalonike and Cynane.

Alexander's death was the catalyst for the disagreements that ensued between his former generals resulting in a succession crisis. Two main factions formed after the death of Alexander. The first of these was led by Meleager, who supported the candidacy of Alexander's half-brother, Arrhidaeus. The second was led by Perdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, Περδίκκας, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to becom ...

, the leading cavalry commander, who believed it would be best to wait until the birth of Alexander's unborn child, by Roxana

Roxana (c. 340 BC – 310 BC, grc, Ῥωξάνη; Old Iranian: ''*Raṷxšnā-'' "shining, radiant, brilliant"; sometimes Roxanne, Roxanna, Rukhsana, Roxandra and Roxane) was a Sogdian or a Bactrian princess whom Alexander the Great married ...

. Both parties agreed to a compromise, wherein Arrhidaeus would become king as Philip III and rule jointly with Roxana's child

A child ( : children) is a human being between the stages of birth and puberty, or between the developmental period of infancy and puberty. The legal definition of ''child'' generally refers to a minor, otherwise known as a person young ...

, providing it was a male heir. Perdiccas was designated as regent of the empire, with Meleager acting as his lieutenant. However, soon after, Perdiccas had Meleager and the other leaders who had opposed him murdered, and he assumed full control.

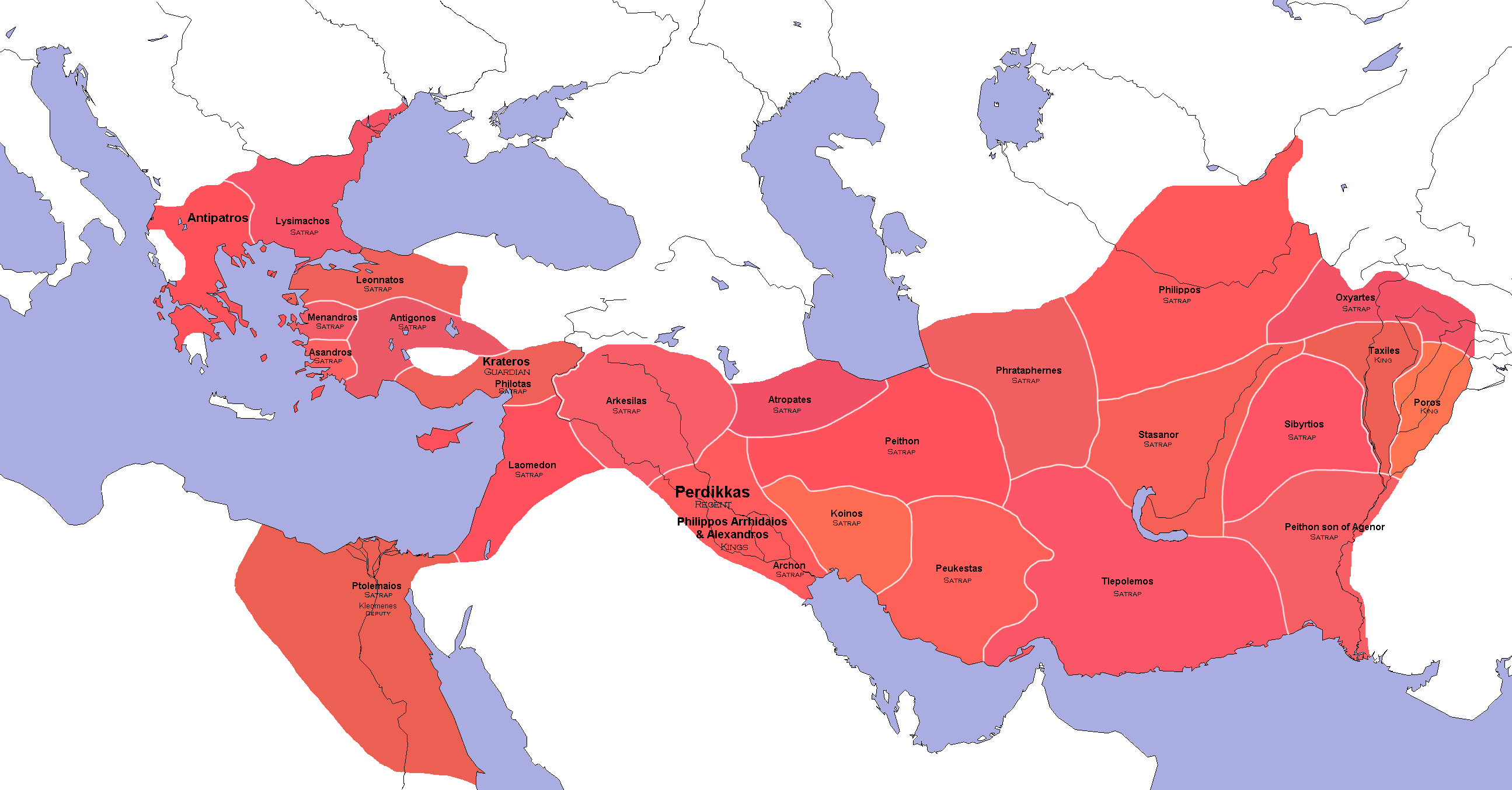

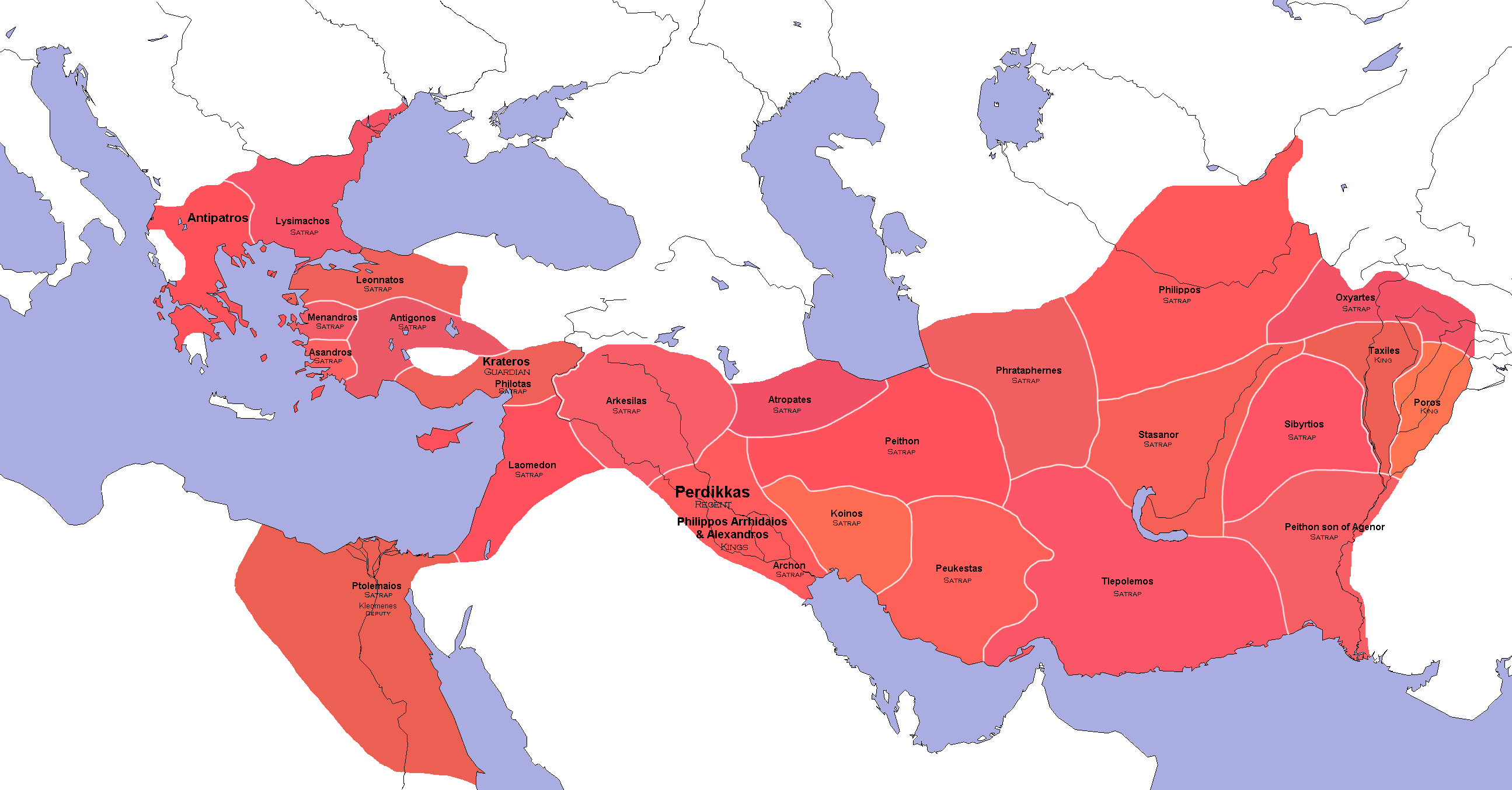

The generals who had supported Perdiccas were rewarded in the partition of Babylon

The Partition of Babylon was the first of the conferences and ensuing agreements that divided the territories of Alexander the Great. It was held at Babylon in June 323 BC.

Alexander’s death at the age of 32 had left an empire that stretched fro ...

by becoming satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with cons ...

s of the various parts of the empire. Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

received Egypt; Laomedon received Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

; Philotas took Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

; Peithon

Peithon or Pithon ( Greek: ''Πείθων'' or ''Πίθων'', 355 – 314 BC) was the son of Crateuas, a nobleman from Eordaia in western Macedonia. He was famous for being one of the bodyguards of Alexander the Great, becoming the lat ...

took Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Broadcast media, communications delivered over mass e ...

; Antigonus received Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empir ...

, Lycia

Lycia ( Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is ...

and Pamphylia

Pamphylia (; grc, Παμφυλία, ''Pamphylía'') was a region in the south of Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (all in modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the north b ...

; Asander received Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joine ...

; Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His ...

received Lydia

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern western Turkish pro ...

; Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Early life and career

Lysimachus wa ...

received Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

; Leonnatus

Leonnatus ( el, Λεοννάτος; 356 BC – 322 BC) was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great and one of the ''diadochi.''

He was a member of the royal house of Lyncestis, a small Greek kingdom that had been included in Macedonia by Kin ...

received Hellespontine Phrygia; and Neoptolemus

In Greek mythology, Neoptolemus (; ), also called Pyrrhus (; ), was the son of the warrior Achilles and the princess Deidamia, and the brother of Oneiros. He became the mythical progenitor of the ruling dynasty of the Molossians of ancient Ep ...

had Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

. Macedon and the rest of Greece were to be under the joint rule of Antipater

Antipater (; grc, , translit=Antipatros, lit=like the father; c. 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general and statesman under the subsequent kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collaps ...

, who had governed them for Alexander, and Craterus

Craterus or Krateros ( el, Κρατερός; c. 370 BC – 321 BC) was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great and one of the Diadochi. Throughout his life he was a loyal royalist and supporter of Alexander the Great.Anson, Edward M. (20 ...

, a lieutenant of Alexander. Alexander's secretary, Eumenes of Cardia, was to receive Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

and Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; el, Παφλαγονία, Paphlagonía, modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; tr, Paflagonya) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus t ...

.

In the east, Perdiccas largely left Alexander's arrangements intact – Taxiles

Taxiles (in Greek Tαξίλης or Ταξίλας; lived 4th century BC) was the Greek chroniclers' name for the ruler who reigned over the tract between the Indus and the Jhelum (Hydaspes) Rivers in the Punjab region at the time of Alexand ...

and Porus ruled over their kingdoms in India; Alexander's father-in-law Oxyartes

Oxyartes (Old Persian: 𐎢𐎺𐎧𐏁𐎫𐎼, Greek: ''Ὀξυάρτης'', in fa, وخشارد ("Vaxš-ard"), from an unattested form in an Old Iranian language: ''*Huxšaθra-'') was a Sogdian or Bactrian nobleman of Bactria, father o ...

ruled Gandara; Sibyrtius ruled Arachosia

Arachosia () is the Hellenized name of an ancient satrapy situated in the eastern parts of the Achaemenid empire. It was centred around the valley of the Arghandab River in modern-day southern Afghanistan, and extended as far east as the In ...

and Gedrosia; Stasanor ruled Aria

In music, an aria ( Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompa ...

and Drangiana; Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who populariz ...

ruled Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, sou ...

and Sogdiana

Sogdia ( Sogdian: ) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also a province of the Achaemenid Empi ...

; Phrataphernes ruled Parthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Med ...

and Hyrcania

Hyrcania () ( el, ''Hyrkania'', Old Persian: 𐎺𐎼𐎣𐎠𐎴 ''Varkâna'',Lendering (1996) Middle Persian: 𐭢𐭥𐭫𐭢𐭠𐭭 ''Gurgān'', Akkadian: ''Urqananu'') is a historical region composed of the land south-east of the Caspian ...

; Peucestas

Peucestas ( grc, Πευκέστας, ''Peukéstas''; lived 4th century BC) was a native of the town of Mieza, in Macedonia, and a distinguished officer in the service of Alexander the Great. His name is first mentioned as one of those appointed t ...

governed Persis

Persis ( grc-gre, , ''Persís''), better known in English as Persia ( Old Persian: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿, ''Parsa''; fa, پارس, ''Pârs''), or Persia proper, is the Fars region, located to the southwest of modern-day Iran, now a province. T ...

; Tlepolemus had charge over Carmania; Atropates

Atropates ( peo, *Ātr̥pātaʰ and Middle Persian ; grc, Ἀτροπάτης ; c. 370 BC - after 321 BC) was a Persian nobleman who served Darius III, then Alexander the Great, and eventually founded an independent kingdom and dynasty that wa ...

governed northern Media; Archon

''Archon'' ( gr, ἄρχων, árchōn, plural: ἄρχοντες, ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem αρχ-, mean ...

got Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

; and, Arcesilas ruled northern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

.

Lamian War

The news of Alexander's death inspired a revolt in Greece, known as the Lamian War.Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

and other cities formed a coalition and besieged Antipater in the fortress of Lamia

LaMia Corporation S.R.L., operating as LaMia (short for ''Línea Aérea Mérida Internacional de Aviación''), was a Bolivian charter airline headquartered in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, as an EcoJet subsidiary. It had its origins from the failed ...

, however, Antipater was relieved by a force sent by Leonnatus

Leonnatus ( el, Λεοννάτος; 356 BC – 322 BC) was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great and one of the ''diadochi.''

He was a member of the royal house of Lyncestis, a small Greek kingdom that had been included in Macedonia by Kin ...

, who was killed in battle. The Athenians were defeated at the Battle of Crannon on September 5, 322 BC by Craterus and his fleet.

At this time, Peithon suppressed a revolt of Greek settlers in the eastern parts of the empire, and Perdiccas and Eumenes subdued Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

.

First War of the Diadochi, 322–319 BC

Perdiccas, who was already betrothed to the daughter of Antipater, attempted to marry Alexander's sister, Cleopatra, a marriage which would have given him claim to the Macedonian throne. In 322 BC, Antipater, Craterus and Antigonus all formed a coalition against Perdiccas's growing power. Soon after, Antipater would send his army, under the command of Craterus, into Asia Minor. In late 322 or early 321 BC,

Perdiccas, who was already betrothed to the daughter of Antipater, attempted to marry Alexander's sister, Cleopatra, a marriage which would have given him claim to the Macedonian throne. In 322 BC, Antipater, Craterus and Antigonus all formed a coalition against Perdiccas's growing power. Soon after, Antipater would send his army, under the command of Craterus, into Asia Minor. In late 322 or early 321 BC, Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

stole Alexander's body on its way to Macedonia and then joined the coalition. A force under Eumenes defeated Craterus at the battle of the Hellespont

The Battle of the Hellespont, consisting of two separate naval clashes, was fought in 324 between a Constantinian fleet, led by the eldest son of Constantine I, Crispus; and a larger fleet under Licinius' admiral, Abantus (or Amandus). Despite ...

, however, Perdiccas was soon after murdered by his own generals Peithon

Peithon or Pithon ( Greek: ''Πείθων'' or ''Πίθων'', 355 – 314 BC) was the son of Crateuas, a nobleman from Eordaia in western Macedonia. He was famous for being one of the bodyguards of Alexander the Great, becoming the lat ...

, Seleucus, and Antigenes during his invasion of Egypt, after a failed attempt to cross the Nile.

Ptolemy came to terms with Perdiccas' murderers, making Peithon and Arrhidaeus

Arrhidaeus or Arrhidaios ( el, Ἀρριδαῖoς lived 4th century BC), one of Alexander the Great's generals, was entrusted by Ptolemy to bring Alexander's body to Egypt in 323 BC, contrary to the wishes of Perdiccas who wanted the body sent t ...

regents in Perdiccas's place, but soon these came to a new agreement with Antipater at the Treaty of Triparadisus. Antipater was made Regent of the Empire, and the two kings were moved to Macedon. Antigonus was made Strategos

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek to mean military general. In the Helleni ...

of Asia and remained in charge of Phrygia, Lycia, and Pamphylia, to which was added Lycaonia

Lycaonia (; el, Λυκαονία, ''Lykaonia''; tr, Likaonya) was a large region in the interior of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), north of the Taurus Mountains. It was bounded on the east by Cappadocia, on the north by Galatia, on the west b ...

. Ptolemy retained Egypt, Lysimachus retained Thrace, while the three murderers of Perdiccas—Seleucus, Peithon, and Antigenes—were given the provinces of Babylonia, Media, and Susiana respectively. Arrhidaeus, the former regent, received Hellespontine Phrygia. Antigonus was charged with the task of rooting out Perdiccas's former supporter, Eumenes. In effect, Antipater retained for himself control of Europe, while Antigonus, as Strategos of the East, held a similar position in Asia.

Although the First War ended with the death of Perdiccas, his cause lived on. Eumenes was still at large with a victorious army in Asia Minor. So were Alcetas, Attalus, Dokimos and Polemon who had also gathered their armies in Asia Minor. In 319 BC Antigonus, after receiving reinforcements from Antipater's European army, first campaigned against Eumenes (see: battle of Orkynia), then against the combined forces of Alcetas, Attalus, Dokimos and Polemon (see: battle of Cretopolis

The Battle of Cretopolis (Kretopolis) was a battle in the wars of the successors of Alexander the Great (see Diadochi) between general Antigonus Monopthalmus and the remnants of the Perdiccan faction. It was fought near Cretopolis in Pisidia ...

), defeating them all.

Second War of the Diadochi, 318–315 BC

Another war soon broke out between the Diadochi. At the start of 318 BC Arrhidaios, the governor of Hellespontine Phrygia, tried to take the city ofCyzicus

Cyzicus (; grc, Κύζικος ''Kúzikos''; ota, آیدینجق, ''Aydıncıḳ'') was an ancient Greek town in Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peni ...

. Antigonus, as the Strategos

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek to mean military general. In the Helleni ...

of Asia, took this as a challenge to his authority and recalled his army from their winter quarters. He sent an army against Arrhidaios while he himself marched with the main army into Lydia

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern western Turkish pro ...

against its governor Cleitus whom he drove out of his province.

Cleitus fled to Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled ...

and joined Polyperchon, the new Regent of the Empire, who decided to march his army south to force the Greek cities to side with him against Cassander and Antigonus. Cassander, reinforced with troops and a fleet by Antigonus, sailed to Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

and thwarted Polyperchon's efforts to take the city. From Athens Polyperchon marched on Megalopolis which had sided with Cassander and besieged the city. The siege failed and he had to retreat losing a lot of prestige and most of the Greek cities. Eventually Polyperchon retreated to Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

with the infant King Alexander IV. There he joined forces with Alexander's mother Olympias

Olympias ( grc-gre, Ὀλυμπιάς; c. 375–316 BC) was a Greek princess of the Molossians, and the eldest daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip II, the king of Macedoni ...

and was able to re-invade Macedon. King Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother, having defected to Cassander's side at the prompting of his wife, Eurydice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the na ...

, was forced to flee, only to be captured in Amphipolis

Amphipolis ( ell, Αμφίπολη, translit=Amfipoli; grc, Ἀμφίπολις, translit=Amphipolis) is a municipality in the Serres regional unit, Macedonia, Greece. The seat of the municipality is Rodolivos. It was an important ancient Gr ...

, resulting in the execution of himself and the forced suicide of his wife, both purportedly at the instigation of Olympias. Cassander rallied once more, and seized Macedon. Olympias

Olympias ( grc-gre, Ὀλυμπιάς; c. 375–316 BC) was a Greek princess of the Molossians, and the eldest daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip II, the king of Macedoni ...

was murdered, and Cassander gained control of the infant King and his mother. Eventually, Cassander became the dominant power in the European part of the Empire, ruling over Macedon and large parts of Greece.

Meanwhile, Eumenes, who had gathered a small army in Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

, had entered the coalition of Polyperchon and Olympias. He took his army to the royal treasury at Kyinda in Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

where he used its funds to recruit mercenaries. He also secured the loyalty of 6,000 of Alexander's veterans, the Argyraspides (the Silver Shields) and the Hypaspists, who were stationed in Cilicia. In the spring of 317 BC he marched his army to Phoenica and began to raise a naval force on the behalf of Polyperchon. Antigonus had spent the rest of 318 BC consolidating his position and gathering a fleet. He now used this fleet (under the command of Nicanor who had returned from Athens) against Polyperchon's fleet in the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. In a two-day battle near Byzantium, Nicanor and Antigonus destroyed Polyperchon's fleet. Then, after settling his affairs in western Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, Antigonus marched against Eumenes at the head of a great army. Eumenes hurried out of Phoenicia and marched his army east to gather support in the eastern provinces. In this he was successful, because most of the eastern satraps

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

joined his cause (when he arrived in Susiana) more than doubling his army. They marched and counter-marched throughout Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

, Susiana and Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Broadcast media, communications delivered over mass e ...

until they faced each other on a plain in the country of the Paraitakene in southern Media. There they fought a great battle − the battle of Paraitakene− which ended inconclusively. The next year (315) they fought another great but inconclusive battle − the battle of Gabiene− during which some of Antigonus's troops plundered the enemy camp. Using this plunder as a bargaining tool, Antigonus bribed the Argyraspides who arrested and handed over Eumenes.Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

, ''Bibliotheca Historica

''Bibliotheca historica'' ( grc, Βιβλιοθήκη Ἱστορική, ) is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, ...

'' XIX 43,8–44,3; Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, ''Parallel Lives

Plutarch's ''Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans'', commonly called ''Parallel Lives'' or ''Plutarch's Lives'', is a series of 48 biographies of famous men, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues or failings, probably writt ...

'' Eumenes 17,1–19,1; Cornelius Nepos

Cornelius Nepos (; c. 110 BC – c. 25 BC) was a Roman biographer. He was born at Hostilia, a village in Cisalpine Gaul not far from Verona.

Biography

Nepos's Cisalpine birth is attested by Ausonius, and Pliny the Elder calls him ''Pad ...

, ''Parallel Lives, Eumenes 10,3–13,1. Antigonus had Eumenes and a couple of his officers executed. With Eumenes's death, the war in the eastern part of the Empire ended.

Antigonus and Cassander had won the war. Antigonus now controlled Asia Minor and the eastern provinces, Cassander controlled Macedon and large parts of Greece, Lysimachus controlled Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, and Ptolemy controlled Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Syria, Cyrene and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

. Their enemies were either dead or seriously reduced in power and influence.

Third War of the Diadochi, 314–311 BC

Though his authority had seemed secure with his victory over Eumenes, the eastern dynasts were unwilling to see Antigonus rule all of Asia. In 314 BC they demanded from Antigonus that he cede Lycia and Cappadocia to Cassander, Hellepontine Phrygia to Lysimachus, all of Syria to Ptolemy, and Babylonia to Seleucus, and that he share the treasures he had captured. Antigonus only answer was to advise them to be ready, then, for war. In this war, Antigonus faced an alliance of Ptolemy (with Seleucus serving him), Lysimachus, and Cassander. At the start of the campaigning season of 314 BC Antigonus invaded Syria andPhoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

, which were under Ptolemy's control, and besieged Tyre. Cassander and Ptolemy started supporting Asander (satrap of Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joine ...

) against Antigonus who ruled the neighbouring provinces of Lycia, Lydia and Greater Phrygia. Antigonus then sent Aristodemus

In Greek mythology, Aristodemus (Ancient Greek: Ἀριστόδημος) was one of the Heracleidae, son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Temenus. He was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final attac ...

with 1,000 talents to the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

to raise a mercenary army to fight Cassander, he allied himself to Polyperchon, who still controlled parts of the Peloponnese, and he proclaimed freedom for the Greeks to get them on their side. He also sent his nephew Ptolemaios Ptolemy is a name derived from Ancient Greek. Common variants include Ptolemaeus (Latin), Tolomeo (Italian) and Talmai (Hebrew).

Etymology

Ptolemy is the English form of the Ancient Greek name Πτολεμαῖος (''Ptolemaios''), a derivative o ...

with an army through Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

to the Hellespont to cut Asander off from Lysimachus and Cassander. Polemaios was successful, securing the northwest of Asia Minor for Antigonus, even invading Ionia/Lydia and bottling up Asander in Caria, but he was unable to drive his opponent from his satrapy.

Eventually Antigonus decided to campaign against Asander himself, leaving his oldest son Demetrius

Demetrius is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning “Demetris” - "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, Dimitri, Dimitrie, Dimitar, Dumi ...

to protect Syria and Phoenica against Ptolemy. Ptolemy and Seleucus invaded from Egypt and defeated Demetrius in the Battle of Gaza. After the battle, Seleucus went east and secured control of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

(his old satrapy), and then went on to secure the eastern satrapies of Alexander's empire. Antigonus, having defeated Asander, sent his nephews Telesphorus Telesphorus can refer to:

* Telesphorus (general), 4th century BC general in ancient Greece

* Pope Telesphorus (died c. 137), Catholic pope and Catholic and Orthodox saint

* Telesphorus of Cosenza, a name assumed by a 14th century pseudo-prophet d ...

and Polemaios to Greece to fight Cassander, he himself returned to Syria/Phoenica, drove off Ptolemy, and sent Demetrius east to take care of Seleucus. Although Antigonus now concluded a compromise peace with Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Cassander, he continued the war with Seleucus, attempting to recover control of the eastern reaches of the empire. Although he went east himself in 310 BC, he was unable to defeat Seleucus (he even lost a battle to Seleucus) and had to give up the eastern satrapies.

At about the same time, Cassander had young King Alexander IV and his mother Roxane murdered, ending the Argead dynasty, which had ruled Macedon for several centuries. As Cassander did not publicly announce the deaths, all of the various generals continued to recognize the dead Alexander as king, however, it was clear that at some point, one or all of them would claim the kingship. At the end of the war there were five Diadochi left: Cassander ruling Macedon and Thessaly, Lysimachus ruling Thrace, Antigonus ruling Asia Minor, Syria and Phoenicia, Seleucus ruling the eastern provinces and Ptolemy ruling Egypt and Cyprus. Each of them ruled as kings (in all but name).

Babylonian War, 311–309 BC

The Babylonian War was a conflict fought between 311 and 309 BC between theDiadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

kings Antigonus I Monophthalmus

Antigonus I Monophthalmus ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Μονόφθαλμος , 'the One-Eyed'; 382 – 301 BC), son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian Greek nobleman, general, satrap, and king. During the first half of his life he serv ...

and Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

, ending in a victory for the latter, Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

. The conflict ended any possibility of restoration of the empire of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, a result confirmed in the Battle of Ipsus

The Battle of Ipsus ( grc, Ἱψός) was fought between some of the Diadochi (the successors of Alexander the Great) in 301 BC near the town of Ipsus in Phrygia. Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the Macedonian ruler of large parts of Asia, and his ...

.

Fourth War of the Diadochi, 308–301 BC

Ptolemy had been expanding his power into the Aegean and toCyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, while Seleucus went on a tour of the east to consolidate his control of the vast eastern territories of Alexander's empire. Antigonus resumed the war, sending his son Demetrius

Demetrius is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning “Demetris” - "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, Dimitri, Dimitrie, Dimitar, Dumi ...

to regain control of Greece. In 307 he took Athens, expelling Demetrius of Phaleron, Cassander's governor, and proclaiming the city free again. Demetrius now turned his attention to Ptolemy, invading Cyprus and defeating Ptolemy's fleet at the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

. In the aftermath of this victory, Antigonus and Demetrius both assumed the crown, and they were shortly followed by Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and eventually Cassander.

In 306, Antigonus attempted to invade Egypt, but storms prevented Demetrius' fleet from supplying him, and he was forced to return home. Now, with Cassander and Ptolemy both weakened, and Seleucus still occupied in the East, Antigonus and Demetrius turned their attention to Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, which was besieged by Demetrius's forces in 305 BC. The island was reinforced by troops from Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Cassander. Ultimately, the Rhodians reached a compromise with Demetrius – they would support Antigonus and Demetrius against all enemies, save their great ally Ptolemy. Ptolemy took the title of ''Soter'' ("Savior") for his role in preventing the fall of Rhodes, but the victory was ultimately Demetrius's, as it left him with a free hand to attack Cassander in Greece.

At the beginning of 304, Cassander managed to capture Salamis and besieged Athens.Plut. ''Dem''. 23,1. Athens petitioned Antigonus and Demetrius to come to their aid. Demetrius gathered a large fleet and landed his army in Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its ...

in the rear of Cassander's forces. He freed the cities of Chalkis

Chalcis ( ; Ancient Greek & Katharevousa: , ) or Chalkida, also spelled Halkida (Modern Greek: , ), is the chief town of the island of Euboea or Evia in Greece, situated on the Euripus Strait at its narrowest point. The name is preserved from ...

and Eretria

Eretria (; el, Ερέτρια, , grc, Ἐρέτρια, , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th centur ...

, renewed the alliance with the Boeotian League and the Aetolian League

The Aetolian (or Aitolian) League ( grc-gre, Κοινὸν τῶν Αἰτωλῶν) was a confederation of tribal communities and cities in ancient Greece centered in Aetolia in central Greece. It was probably established during the early Hellen ...

, raised the siege of Athens and drove Cassander's forces from central Greece. In the spring of 303, Demetrius marched his army into the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

and took the cities of Sicyon

Sicyon (; el, Σικυών; ''gen''.: Σικυῶνος) or Sikyon was an ancient Greek city state situated in the northern Peloponnesus between Corinth and Achaea on the territory of the present-day regional unit of Corinthia. An ancient mon ...

and Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

, he then campaigned in Argolis

Argolis or Argolida ( el, Αργολίδα , ; , in ancient Greek and Katharevousa) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Peloponnese, situated in the eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula and part of the ...

, Achaea

Achaea () or Achaia (), sometimes transliterated from Greek as Akhaia (, ''Akhaïa'' ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Western Greece and is situated in the northwestern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. T ...

and Arcadia, bringing the northern and central Peloponnese into the Antigonid camp.Diod. XX, 102–104. In 303–302 Demetrius formed a new Hellenic League, ''the League of Corinth'', with himself and his father as presidents, to "defend" the Greek cities against all enemies (and particularly Cassander).

In the face of these catastrophes, Cassander sued for peace, but Antigonus rejected the claims, and Demetrius invaded Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

, where he and Cassander battled in inconclusive engagements. But now Cassander called in aid from his allies, and Anatolia was invaded by Lysimachus, forcing Demetrius to leave Thessaly and send his armies to Asia Minor to assist his father. With assistance from Cassander, Lysimachus overran much of western Anatolia, but was soon (301 BC) isolated by Antigonus and Demetrius near Ipsus. Here came the decisive intervention from Seleucus, who arrived in time to save Lysimachus from disaster and utterly crush Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus

The Battle of Ipsus ( grc, Ἱψός) was fought between some of the Diadochi (the successors of Alexander the Great) in 301 BC near the town of Ipsus in Phrygia. Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the Macedonian ruler of large parts of Asia, and his ...

. Antigonus was killed in the fight, and Demetrius fled back to Greece to attempt to preserve the remnants of his rule there. Lysimachus and Seleucus divided up Antigonus's Asian territories between them, with Lysimachus receiving western Asia Minor and Seleucus the rest, except Cilicia and Lycia, which went to Cassander's brother Pleistarchus

Pleistarchus ( grc-gre, Πλείσταρχος ; died c. 458 BC) was the Agiad King of Sparta from 480 to 458 BC.

Biography

Pleistarchus was born as a prince, likely the only son of King Leonidas I and Queen Gorgo. His grandparents were King ...

.

The struggle over Macedon, 298–285 BC

The events of the next decade and a half were centered around various intrigues for control of Macedon itself. Cassander died in 298 BC, and his sons,Antipater

Antipater (; grc, , translit=Antipatros, lit=like the father; c. 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general and statesman under the subsequent kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collaps ...

and Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, proved weak kings. After quarreling with his older brother, Alexander V called in Demetrius, who had retained control of Cyprus, the Peloponnese, and many of the Aegean islands, and had quickly seized control of Cilicia and Lycia from Cassander's brother, as well as Pyrrhus, the King of Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

. After Pyrrhus had intervened to seize the border region of Ambracia

Ambracia (; grc-gre, Ἀμβρακία, occasionally , ''Ampracia'') was a city of ancient Greece on the site of modern Arta. It was captured by the Corinthians in 625 BC and was situated about from the Ambracian Gulf, on a bend of the navigabl ...

, Demetrius invaded, killed Alexander, and seized control of Macedon for himself (294 BC). While Demetrius consolidated his control of mainland Greece, his outlying territories were invaded and captured by Lysimachus (who recovered western Anatolia), Seleucus (who took most of Cilicia), and Ptolemy (who recovered Cyprus, eastern Cilicia, and Lycia).

Soon, Demetrius was forced from Macedon by a rebellion supported by the alliance of Lysimachus and Pyrrhus, who divided the Kingdom between them, and, leaving Greece to the control of his son, Antigonus Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Γονατᾶς, ; – 239 BC) was a Macedonian ruler who solidified the position of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedon after a long period defined by anarchy and chaos and acquired fame for h ...

, Demetrius launched an invasion of the east in 287 BC. Although initially successful, Demetrius was ultimately captured by Seleucus (286 BC), drinking himself to death two years later.

The struggle of Lysimachus and Seleucus, 285–281 BC

Although Lysimachus and Pyrrhus had cooperated in driving Antigonus Gonatas from Thessaly and Athens, in the wake of Demetrius's capture they soon fell out, with Lysimachus driving Pyrrhus from his share of Macedon. Dynastic struggles also rent Egypt, where Ptolemy decided to make his younger son Ptolemy Philadelphus his heir rather than the elder,Ptolemy Ceraunus

Ptolemy Ceraunus ( grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος Κεραυνός ; c. 319 BC – January/February 279 BC) was a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty and briefly king of Macedon. As the son of Ptolemy I Soter, he was originally heir to the thro ...

. Ceraunus fled to Seleucus. The eldest Ptolemy died peacefully in his bed in 282 BC, and Philadelphus succeeded him.

In 282 BC Lysimachus had his son Agathocles Agathocles ( Greek: ) is a Greek name, the most famous of which is Agathocles of Syracuse, the tyrant of Syracuse. The name is derived from , ''agathos'', i.e. "good" and , ''kleos'', i.e. "glory".

Other personalities named Agathocles:

*Agathocles ...

murdered, possibly at the behest of his second wife, Arsinoe II

Arsinoë II ( grc-koi, Ἀρσινόη, 316 BC – unknown date between July 270 and 260 BC) was a Ptolemaic queen and co-regent of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of ancient Egypt. She was given the Egyptian title "King of Upper and Lower Egypt", makin ...

. Agathocles's widow, Lysandra

Lysandra (Greek: Λυσάνδρα, meaning "Liberator, Emancipator"; lived 281 BC) was a Queen of Macedonia, daughter of Ptolemy I Soter to Eurydice or Berenice.

She was married first to her maternal cousin Alexander, one of the sons of Cassan ...

, fled to Seleucus, who after appointing his son Antiochus ruler of his Asian territories, defeated and killed Lysimachus at the Battle of Corupedium in Lydia in 281 BC. Selucus hoped to take control of Lysimachus' European territories, and in 281 BC, soon after arriving in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, he was assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus, for reasons that remain unclear.

The Gallic invasions and consolidation, 280–275 BC

Ptolemy Ceraunus did not rule Macedon for very long. The death of Lysimachus had left theDanube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

border of the Macedonian kingdom open to barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be less ...

invasions, and soon tribes of Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

were rampaging through Macedon and Greece, and invading Asia Minor. Ptolemy Ceraunus was killed by the invaders, and after several years of chaos, Demetrius's son Antigonus Gonatas emerged as ruler of Macedon. In Asia, Seleucus's son, Antiochus I, also managed to defeat the Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic invaders, who settled down in central Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

in the part of eastern Phrygia that would henceforward be known as Galatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace ...

after them.

Now, almost fifty years after Alexander's death, some sort of order was restored. Ptolemy ruled over Egypt, southern Syria (known as Coele-Syria

Coele-Syria (, also spelt Coele Syria, Coelesyria, Celesyria) alternatively Coelo-Syria or Coelosyria (; grc-gre, Κοίλη Συρία, ''Koílē Syría'', 'Hollow Syria'; lat, Cœlē Syria or ), was a region of Syria in classical antiqui ...

), and various territories on the southern coast of Asia Minor. Antiochus ruled the Asian territories of the empire, while Macedon and Greece (with the exception of the Aetolian League

The Aetolian (or Aitolian) League ( grc-gre, Κοινὸν τῶν Αἰτωλῶν) was a confederation of tribal communities and cities in ancient Greece centered in Aetolia in central Greece. It was probably established during the early Hellen ...

) fell to Antigonus.

Aftermath

References

*Shipley, Graham (2000) ''The Greek World After Alexander''. Routledge History of the Ancient World. (Routledge, New York) * Walbank, F. W. (1984) ''The Hellenistic World'', The Cambridge Ancient History, volume VII. part I. (Cambridge) *External links

Alexander's successors: the Diadochi

from Livius.org (Jona Lendering)

Wiki Classical Dictionary: "Successors" category

an

Diadochi entry

T. Boiy, "Dating Methods During the Early Hellenistic Period", ''Journal of Cuneiform Studies'', Vol. 52, 2000

''PDF format''. A recent study of primary sources for the chronology of eastern rulers during the period of the Diadochi. {{Authority control Macedonian Empire 4th century BC in Macedonia (ancient kingdom) 3rd century BC in Macedonia (ancient kingdom) 290s BC conflicts 280s BC conflicts 270s BC conflicts Wars involving Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

Diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

Diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

Diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...