Definition of planet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

While knowledge of the planets predates history and is common to most civilizations, the word ''planet'' dates back to

While knowledge of the planets predates history and is common to most civilizations, the word ''planet'' dates back to  In his ''

In his ''

Medieval and Renaissance writers generally accepted the idea of seven planets. The standard medieval introduction to astronomy,

Medieval and Renaissance writers generally accepted the idea of seven planets. The standard medieval introduction to astronomy,

Eventually, when Copernicus's

Eventually, when Copernicus's

In 1781, the astronomer

In 1781, the astronomer

When Copernicus placed Earth among the planets, he also placed the Moon in orbit around Earth, making the Moon the first

When Copernicus placed Earth among the planets, he also placed the Moon in orbit around Earth, making the Moon the first

One of the unexpected results of

One of the unexpected results of

The long road from planethood to reconsideration undergone by Ceres is mirrored in the story of

The long road from planethood to reconsideration undergone by Ceres is mirrored in the story of

* A planet is any object in

* A planet is any object in

orig link

) The IAU also resolved that "''planets'' and ''dwarf planets'' are two distinct classes of objects", meaning that dwarf planets, despite their name, would not be considered planets. On September 13, 2006, the IAU placed Eris, its moon Dysnomia, and Pluto into their

Among the most vocal proponents of the IAU's decided definition are Mike Brown, the discoverer of Eris;

Among the most vocal proponents of the IAU's decided definition are Mike Brown, the discoverer of Eris;

Mike Brown counters these claims by saying that, far from not having cleared their orbits, the major planets completely control the orbits of the other bodies within their orbital zone. Jupiter may coexist with a large number of small bodies in its orbit (the Trojan asteroids), but these bodies only exist in Jupiter's orbit because they are in the sway of the planet's huge gravity. Similarly, Pluto may cross the orbit of Neptune, but Neptune long ago locked Pluto and its attendant Kuiper belt objects, called plutinos, into a 3:2 resonance, i.e., they orbit the Sun twice for every three Neptune orbits. The orbits of these objects are entirely dictated by Neptune's gravity, and thus, Neptune is gravitationally dominant.

In October 2015, astronomer Jean-Luc Margot of the University of California Los Angeles proposed a metric for orbital zone clearance derived from whether an object can clear an orbital zone of extent 2 of its Hill radius in a specific time scale. This metric places a clear dividing line between the dwarf planets and the planets of the solar system. The calculation is based on the mass of the host star, the mass of the body, and the orbital period of the body. An Earth-mass body orbiting a solar-mass star clears its orbit at distances of up to 400 astronomical units from the star. A Mars-mass body at the orbit of Pluto clears its orbit. This metric, which leaves Pluto as a dwarf planet, applies to both the Solar System and to extrasolar systems.

Some opponents of the definition have claimed that "clearing the neighbourhood" is an ambiguous concept. Mark Sykes, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and organiser of the petition, expressed this opinion to National Public Radio. He believes that the definition does not categorise a planet by composition or formation, but, effectively, by its location. He believes that a Mars-sized or larger object beyond the orbit of Pluto would not be considered a planet, because he believes that it would not have time to clear its orbit.

Brown notes, however, that were the "clearing the neighbourhood" criterion to be abandoned, the number of planets in the Solar System could rise from eight to List of possible dwarf planets, more than 50, with hundreds more potentially to be discovered.

Mike Brown counters these claims by saying that, far from not having cleared their orbits, the major planets completely control the orbits of the other bodies within their orbital zone. Jupiter may coexist with a large number of small bodies in its orbit (the Trojan asteroids), but these bodies only exist in Jupiter's orbit because they are in the sway of the planet's huge gravity. Similarly, Pluto may cross the orbit of Neptune, but Neptune long ago locked Pluto and its attendant Kuiper belt objects, called plutinos, into a 3:2 resonance, i.e., they orbit the Sun twice for every three Neptune orbits. The orbits of these objects are entirely dictated by Neptune's gravity, and thus, Neptune is gravitationally dominant.

In October 2015, astronomer Jean-Luc Margot of the University of California Los Angeles proposed a metric for orbital zone clearance derived from whether an object can clear an orbital zone of extent 2 of its Hill radius in a specific time scale. This metric places a clear dividing line between the dwarf planets and the planets of the solar system. The calculation is based on the mass of the host star, the mass of the body, and the orbital period of the body. An Earth-mass body orbiting a solar-mass star clears its orbit at distances of up to 400 astronomical units from the star. A Mars-mass body at the orbit of Pluto clears its orbit. This metric, which leaves Pluto as a dwarf planet, applies to both the Solar System and to extrasolar systems.

Some opponents of the definition have claimed that "clearing the neighbourhood" is an ambiguous concept. Mark Sykes, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and organiser of the petition, expressed this opinion to National Public Radio. He believes that the definition does not categorise a planet by composition or formation, but, effectively, by its location. He believes that a Mars-sized or larger object beyond the orbit of Pluto would not be considered a planet, because he believes that it would not have time to clear its orbit.

Brown notes, however, that were the "clearing the neighbourhood" criterion to be abandoned, the number of planets in the Solar System could rise from eight to List of possible dwarf planets, more than 50, with hundreds more potentially to be discovered.

The International Astronomical Union, IAU's definition mandates that planets be large enough for their own gravity to form them into a state of hydrostatic equilibrium; this means that they will reach a round, ellipsoidal shape. Up to a certain mass, an object can be irregular in shape, but beyond that point gravity begins to pull an object towards its own centre of mass until the object collapses into an ellipsoid. (None of the large objects of the Solar System are truly spherical. Many are spheroids, and several, such as the larger moons of Saturn and the dwarf planet , have been further distorted into ellipsoids by rapid rotation or tidal forces, but still in hydrostatic equilibrium.)

However, there is no precise point at which an object can be said to have reached hydrostatic equilibrium. As Soter noted in his article, "how are we to quantify the degree of roundness that distinguishes a planet? Does gravity dominate such a body if its shape deviates from a spheroid by 10 percent or by 1 percent? Nature provides no unoccupied gap between round and nonround shapes, so any boundary would be an arbitrary choice." Furthermore, the point at which an object's mass compresses it into an ellipsoid varies depending on the chemical makeup of the object. Objects made of ices, such as Enceladus and Miranda, assume that state more easily than those made of rock, such as Vesta and Pallas. Heat energy, from gravitational collapse, impact event, impacts, tidal forces such as orbital resonances, or radioactive decay, also factors into whether an object will be ellipsoidal or not; Saturn's icy moon Mimas is ellipsoidal (though no longer in hydrostatic equilibrium), but Neptune's larger moon Proteus (moon), Proteus, which is similarly composed but colder because of its greater distance from the Sun, is irregular. In addition, the much larger Iapetus is ellipsoidal but does not have the dimensions expected for its current speed of rotation, indicating that it was once in hydrostatic equilibrium but no longer is, and the same is true for Earth's moon.M. Bursa

The International Astronomical Union, IAU's definition mandates that planets be large enough for their own gravity to form them into a state of hydrostatic equilibrium; this means that they will reach a round, ellipsoidal shape. Up to a certain mass, an object can be irregular in shape, but beyond that point gravity begins to pull an object towards its own centre of mass until the object collapses into an ellipsoid. (None of the large objects of the Solar System are truly spherical. Many are spheroids, and several, such as the larger moons of Saturn and the dwarf planet , have been further distorted into ellipsoids by rapid rotation or tidal forces, but still in hydrostatic equilibrium.)

However, there is no precise point at which an object can be said to have reached hydrostatic equilibrium. As Soter noted in his article, "how are we to quantify the degree of roundness that distinguishes a planet? Does gravity dominate such a body if its shape deviates from a spheroid by 10 percent or by 1 percent? Nature provides no unoccupied gap between round and nonround shapes, so any boundary would be an arbitrary choice." Furthermore, the point at which an object's mass compresses it into an ellipsoid varies depending on the chemical makeup of the object. Objects made of ices, such as Enceladus and Miranda, assume that state more easily than those made of rock, such as Vesta and Pallas. Heat energy, from gravitational collapse, impact event, impacts, tidal forces such as orbital resonances, or radioactive decay, also factors into whether an object will be ellipsoidal or not; Saturn's icy moon Mimas is ellipsoidal (though no longer in hydrostatic equilibrium), but Neptune's larger moon Proteus (moon), Proteus, which is similarly composed but colder because of its greater distance from the Sun, is irregular. In addition, the much larger Iapetus is ellipsoidal but does not have the dimensions expected for its current speed of rotation, indicating that it was once in hydrostatic equilibrium but no longer is, and the same is true for Earth's moon.M. Bursa

Secular Love Numbers and Hydrostatic Equilibrium of Planets

''Earth, Moon, and Planets,'' volume 31, issue 2, pp. 135–140, October 1984 Even Mercury, universally regarded as a planet, is not in hydrostatic equilibrium.Sean Solomon, Larry Nittler & Brian Anderson, eds. (2018) ''Mercury: The View after MESSENGER''. Cambridge Planetary Science series no. 21, Cambridge University Press, pp. 72–73.

The definition specifically excludes

The definition specifically excludes  However, some have suggested that the Moon nonetheless deserves to be called a planet. In 1975, Isaac Asimov noted that the timing of the Moon's orbit is in tandem with the Earth's own orbit around the Sun—looking down on the

However, some have suggested that the Moon nonetheless deserves to be called a planet. In 1975, Isaac Asimov noted that the timing of the Moon's orbit is in tandem with the Earth's own orbit around the Sun—looking down on the

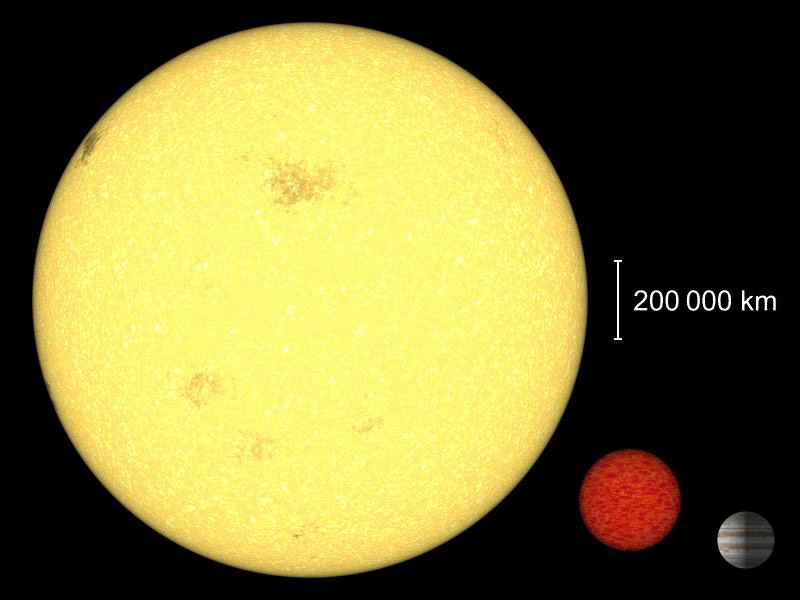

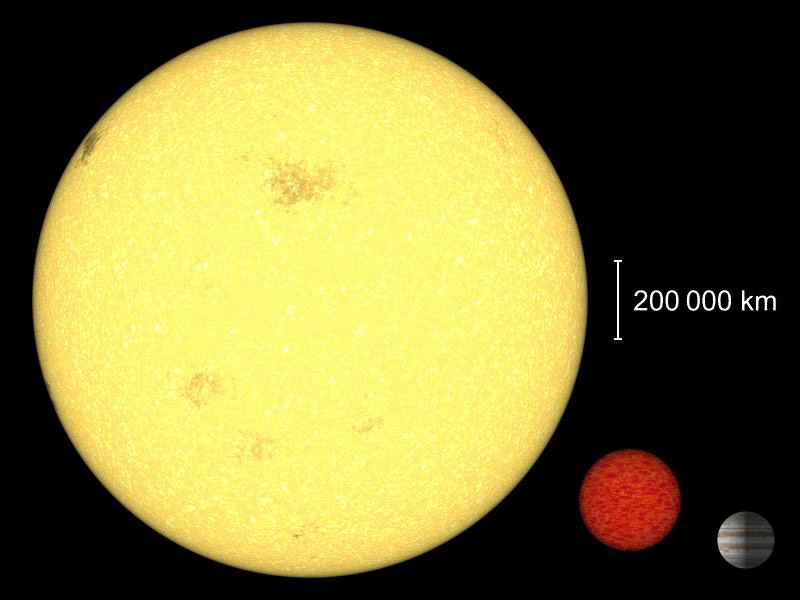

Traditionally, the defining characteristic for starhood has been an object's ability to Nuclear fusion, fuse hydrogen in its core. However, stars such as brown dwarfs have always challenged that distinction. Too small to commence sustained hydrogen-1 fusion, they have been granted star status on their ability to fuse deuterium. However, due to the relative rarity of that isotope, this process lasts only a tiny fraction of the star's lifetime, and hence most brown dwarfs would have ceased fusion long before their discovery. Binary stars and other multiple-star formations are common, and many brown dwarfs orbit other stars. Therefore, since they do not produce energy through fusion, they could be described as planets. Indeed, astronomer Adam Burrows (astronomer), Adam Burrows of the University of Arizona claims that "from the theoretical perspective, however different their modes of formation, extrasolar giant planets and brown dwarfs are essentially the same". Burrows also claims that such stellar remnants as white dwarfs should not be considered stars, a stance which would mean that an orbiting white dwarf, such as Sirius B, could be considered a planet. However, the current convention among astronomers is that any object massive enough to have possessed the capability to sustain atomic fusion during its lifetime and that is not a black hole should be considered a star.

The confusion does not end with brown dwarfs. María Rosa Zapatero Osorio et al. have discovered many objects in young star clusters of masses below that required to sustain fusion of any sort (currently calculated to be roughly 13 Jupiter masses). These have been described as "rogue planet, free floating planets" because current theories of Solar System formation suggest that planets may be ejected from their star systems altogether if their orbits become unstable. However, it is also possible that these "free floating planets" could have formed in the same manner as stars.

Traditionally, the defining characteristic for starhood has been an object's ability to Nuclear fusion, fuse hydrogen in its core. However, stars such as brown dwarfs have always challenged that distinction. Too small to commence sustained hydrogen-1 fusion, they have been granted star status on their ability to fuse deuterium. However, due to the relative rarity of that isotope, this process lasts only a tiny fraction of the star's lifetime, and hence most brown dwarfs would have ceased fusion long before their discovery. Binary stars and other multiple-star formations are common, and many brown dwarfs orbit other stars. Therefore, since they do not produce energy through fusion, they could be described as planets. Indeed, astronomer Adam Burrows (astronomer), Adam Burrows of the University of Arizona claims that "from the theoretical perspective, however different their modes of formation, extrasolar giant planets and brown dwarfs are essentially the same". Burrows also claims that such stellar remnants as white dwarfs should not be considered stars, a stance which would mean that an orbiting white dwarf, such as Sirius B, could be considered a planet. However, the current convention among astronomers is that any object massive enough to have possessed the capability to sustain atomic fusion during its lifetime and that is not a black hole should be considered a star.

The confusion does not end with brown dwarfs. María Rosa Zapatero Osorio et al. have discovered many objects in young star clusters of masses below that required to sustain fusion of any sort (currently calculated to be roughly 13 Jupiter masses). These have been described as "rogue planet, free floating planets" because current theories of Solar System formation suggest that planets may be ejected from their star systems altogether if their orbits become unstable. However, it is also possible that these "free floating planets" could have formed in the same manner as stars.

In 2003, a working group of the IAU released a position statement to establish a working definition as to what constitutes an extrasolar planet and what constitutes a brown dwarf. To date, it remains the only guidance offered by the IAU on this issue. The 2006 planet definition committee did not attempt to challenge it, or to incorporate it into their definition, claiming that the issue of defining a planet was already difficult to resolve without also considering extrasolar planets. This working definition was amended by the IAU's Commission F2: Exoplanets and the Solar System in August 2018. The official working definition of an ''exoplanet'' is now as follows:

The IAU noted that this definition could be expected to evolve as knowledge improves.

In 2003, a working group of the IAU released a position statement to establish a working definition as to what constitutes an extrasolar planet and what constitutes a brown dwarf. To date, it remains the only guidance offered by the IAU on this issue. The 2006 planet definition committee did not attempt to challenge it, or to incorporate it into their definition, claiming that the issue of defining a planet was already difficult to resolve without also considering extrasolar planets. This working definition was amended by the IAU's Commission F2: Exoplanets and the Solar System in August 2018. The official working definition of an ''exoplanet'' is now as follows:

The IAU noted that this definition could be expected to evolve as knowledge improves.

This definition makes location, rather than formation or composition, the determining characteristic for planethood. A free-floating object with a mass below 13 Jupiter masses is a "sub-brown dwarf", whereas such an object in orbit around a fusing star is a planet, even if, in all other respects, the two objects may be identical. Further, in 2010, a paper published by Burrows, David S. Spiegel and John A. Milsom called into question the 13-Jupiter-mass criterion, showing that a brown dwarf of three times solar metallicity could fuse deuterium at as low as 11 Jupiter masses.

Also, the 13 Jupiter-mass cutoff does not have precise physical significance. Deuterium fusion can occur in some objects with mass below that cutoff. The amount of deuterium fused depends to some extent on the composition of the object. As of 2011 the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia included objects up to 25 Jupiter masses, saying, "The fact that there is no special feature around in the observed mass spectrum reinforces the choice to forget this mass limit".

As of 2016 this limit was increased to 60 Jupiter masses based on a study of mass–density relationships. The Exoplanet Data Explorer includes objects up to 24 Jupiter masses with the advisory: "The 13 Jupiter-mass distinction by the IAU Working Group is physically unmotivated for planets with rocky cores, and observationally problematic due to the sin i ambiguity." The NASA Exoplanet Archive includes objects with a mass (or minimum mass) equal to or less than 30 Jupiter masses.

Another criterion for separating planets and brown dwarfs, rather than deuterium burning, formation process or location, is whether the core pressure is dominated by Lateral earth pressure#Coulomb theory, coulomb pressure or electron degeneracy pressure.

One study suggests that objects above formed through gravitational instability and not core accretion and therefore should not be thought of as planets.

A 2016 study shows no noticeable difference between gas giants and brown dwarfs in mass–radius trends: from approximately one Saturn mass to about (the onset of hydrogen burning), radius stays roughly constant as mass increases, and no obvious difference occurs when passing . By this measure, brown dwarfs are more like planets than they are like stars.

This definition makes location, rather than formation or composition, the determining characteristic for planethood. A free-floating object with a mass below 13 Jupiter masses is a "sub-brown dwarf", whereas such an object in orbit around a fusing star is a planet, even if, in all other respects, the two objects may be identical. Further, in 2010, a paper published by Burrows, David S. Spiegel and John A. Milsom called into question the 13-Jupiter-mass criterion, showing that a brown dwarf of three times solar metallicity could fuse deuterium at as low as 11 Jupiter masses.

Also, the 13 Jupiter-mass cutoff does not have precise physical significance. Deuterium fusion can occur in some objects with mass below that cutoff. The amount of deuterium fused depends to some extent on the composition of the object. As of 2011 the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia included objects up to 25 Jupiter masses, saying, "The fact that there is no special feature around in the observed mass spectrum reinforces the choice to forget this mass limit".

As of 2016 this limit was increased to 60 Jupiter masses based on a study of mass–density relationships. The Exoplanet Data Explorer includes objects up to 24 Jupiter masses with the advisory: "The 13 Jupiter-mass distinction by the IAU Working Group is physically unmotivated for planets with rocky cores, and observationally problematic due to the sin i ambiguity." The NASA Exoplanet Archive includes objects with a mass (or minimum mass) equal to or less than 30 Jupiter masses.

Another criterion for separating planets and brown dwarfs, rather than deuterium burning, formation process or location, is whether the core pressure is dominated by Lateral earth pressure#Coulomb theory, coulomb pressure or electron degeneracy pressure.

One study suggests that objects above formed through gravitational instability and not core accretion and therefore should not be thought of as planets.

A 2016 study shows no noticeable difference between gas giants and brown dwarfs in mass–radius trends: from approximately one Saturn mass to about (the onset of hydrogen burning), radius stays roughly constant as mass increases, and no obvious difference occurs when passing . By this measure, brown dwarfs are more like planets than they are like stars.

What is a planet?

-Steven Soter

* An examination of the redefinition of Pluto from a linguistic perspective. * The Pluto Files by

Q&A New planets proposal

Wednesday, August 16, 2006, 13:36 GMT 14:36 UK

"You Call That a Planet?: How astronomers decide whether a celestial body measures up."

* David Darling. ''The Universal Book of Astronomy, from the Andromeda Galaxy to the Zone of Avoidance.'' 2003. John Wiley & Sons Canada (), p. 394 * ''Collins Dictionary of Astronomy'', 2nd ed. 2000. HarperCollins Publishers (), p. 312-4.

Catalogue of Planetary Objects. Version 2006.0

O.V. Zakhozhay, V.A. Zakhozhay, Yu.N. Krugly, 2006

2006-08-22

IAU 2006 General Assembly: video-records of the discussion and of the final vote on the Planet definition.

* Boyle, Alan, ''The Case for Pluto'' The Case for Pluto Book by MSNBC Science Editor and author of "Cosmic Log" * Croswell, Dr. Ken "Pluto Question

{{Authority control Definition of planet, Planetary science Planets of the Solar System Planets History of astronomy Definitions, Planet Astronomical controversies

The

The definition

A definition is a statement of the meaning of a term (a word, phrase, or other set of symbols). Definitions can be classified into two large categories: intensional definitions (which try to give the sense of a term), and extensional definiti ...

of ''planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

'', since the word was coined by the ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, has included within its scope a wide range of celestial bodies. Greek astronomers employed the term (), 'wandering stars', for star-like objects which apparently moved over the sky. Over the millennia, the term has included a variety of different objects, from the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

and the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

to satellites

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotop ...

and asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere. ...

s.

In modern astronomy, there are two primary conceptions of a 'planet'. Disregarding the often inconsistent technical details, they are whether an astronomical body ''dynamically dominates'' its region (that is, whether it controls the fate of other smaller bodies in its vicinity) or whether it is in ''hydrostatic equilibrium'' (that is, whether it looks round). These may be characterized as the dynamical dominance definition and the geophysical definition.

The issue of a clear definition for ''planet'' came to a head in January 2005 with the discovery of the trans-Neptunian object

A trans-Neptunian object (TNO), also written transneptunian object, is any minor planet in the Solar System that orbits the Sun at a greater average distance than Neptune, which has a semi-major axis of 30.1 astronomical units (au).

Typically ...

Eris, a body more massive than the smallest then-accepted planet, Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

. In its August 2006 response, the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

(IAU), recognised by astronomers as the world body responsible for resolving issues of nomenclature

Nomenclature (, ) is a system of names or terms, or the rules for forming these terms in a particular field of arts or sciences. The principles of naming vary from the relatively informal conventions of everyday speech to the internationally ag ...

, released its decision on the matter during a meeting in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. This definition, which applies only to the Solar System (though exoplanets had been addressed in 2003), states that a planet is a body that orbits the Sun, is massive enough for its own gravity to make it round, and has " cleared its neighbourhood" of smaller objects approaching its orbit. Under this formalized definition, Pluto and other trans-Neptunian objects do not qualify as planets. The IAU's decision has not resolved all controversies, and while many astronomers have accepted it, some planetary scientists have rejected it outright, proposing a geophysical or similar definition instead.

History

Planets in antiquity

While knowledge of the planets predates history and is common to most civilizations, the word ''planet'' dates back to

While knowledge of the planets predates history and is common to most civilizations, the word ''planet'' dates back to ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

. Most Greeks believed the Earth to be stationary and at the center of the universe in accordance with the geocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

and that the objects in the sky, and indeed the sky itself, revolved around it (an exception was Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the ...

, who put forward an early version of heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

). Greek astronomers employed the term (), 'wandering stars', to describe those starlike lights in the heavens that moved over the course of the year, in contrast to the (), the 'fixed stars

In astronomy, fixed stars ( la, stellae fixae) is a term to name the full set of glowing points, astronomical objects actually and mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the backgro ...

', which stayed motionless relative to one another. The five bodies currently called "planets" that were known to the Greeks were those visible to the naked eye: Mercury, Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

, and Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

.

Graeco-Roman cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

commonly considered seven planets, with the Sun and the Moon counted among them (as is the case in modern astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

); however, there is some ambiguity on that point, as many ancient astronomers distinguished the five star-like planets from the Sun and Moon. As the 19th-century German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister ...

noted in his work ''Cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

'',

Of the seven cosmical bodies which, by their continually varying relative positions and distances apart, have ever since the remotest antiquity been distinguished from the "unwandering orbs" of the heaven of the "fixed stars", which to all sensible appearance preserve their relative positions and distances unchanged, five only—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn—wear the appearance of stars—"''cinque stellas errantes''"—while the Sun and Moon, from the size of their disks, their importance to man, and the place assigned to them in mythological systems, were classed apart.

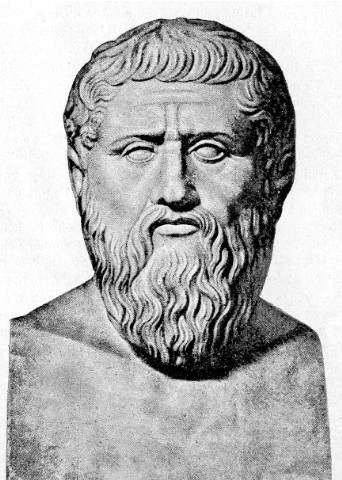

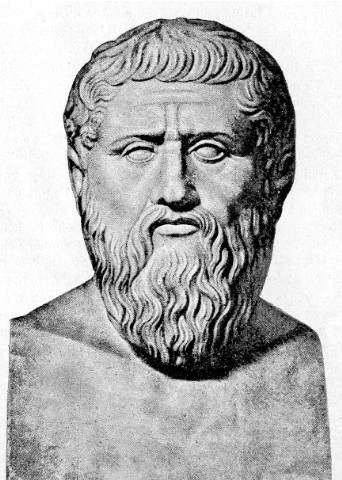

In his ''

In his ''Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

*Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Greek ...

'', written in roughly 360 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

mentions, "the Sun and Moon and five other stars, which are called the planets". His student Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

makes a similar distinction in his ''On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings ...

'': "The movements of the sun and moon are fewer than those of some of the planets". In his ''Phaenomena'', which set to verse an astronomical treatise written by the philosopher Eudoxus in roughly 350 BCE, the poet Aratus

Aratus (; grc-gre, Ἄρατος ὁ Σολεύς; c. 315 BC/310 BC240) was a Greek didactic poet. His major extant work is his hexameter poem ''Phenomena'' ( grc-gre, Φαινόμενα, ''Phainómena'', "Appearances"; la, Phaenomena), the ...

describes "those five other orbs, that intermingle with he constellationsand wheel wandering on every side of the twelve figures of the Zodiac."

In his ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it can ...

'' written in the 2nd century, Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

refers to "the Sun, Moon and five planets." Hyginus

Gaius Julius Hyginus (; 64 BC – AD 17) was a Latin author, a pupil of the scholar Alexander Polyhistor, and a freedman of Caesar Augustus. He was elected superintendent of the Palatine library by Augustus according to Suetonius' ''De Grammati ...

explicitly mentions "the five stars which many have called wandering, and which the Greeks call Planeta." Marcus Manilius

Marcus Manilius (fl. 1st century AD) was a Roman poet, astrologer, and author of a poem in five books called '' Astronomica''.

The ''Astronomica''

The author of ''Astronomica'' is neither quoted nor mentioned by any ancient writer. Even his n ...

, a Latin writer who lived during the time of Caesar Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

and whose poem ''Astronomica'' is considered one of the principal texts for modern astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

, says, "Now the dodecatemory is divided into five parts, for so many are the stars called wanderers which with passing brightness shine in heaven."

The single view of the seven planets is found in Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

's ''Dream of Scipio

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that usually occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep. Humans spend about two hours dreaming per night, and each dream lasts around 5 to 20 minutes, althou ...

'', written sometime around 53 BCE, where the spirit of Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–183 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the best military co ...

proclaims, "Seven of these spheres contain the planets, one planet in each sphere, which all move contrary to the movement of heaven." In his '' Natural History'', written in 77 CE, Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

refers to "the seven stars, which owing to their motion we call planets, though no stars wander less than they do." Nonnus

Nonnus of Panopolis ( grc-gre, Νόννος ὁ Πανοπολίτης, ''Nónnos ho Panopolítēs'', 5th century CE) was the most notable Greek epic poet of the Imperial Roman era. He was a native of Panopolis (Akhmim) in the Egyptian Theb ...

, the 5th century Greek poet, says in his ''Dionysiaca

The ''Dionysiaca'' {{IPAc-en, ˌ, d, aɪ, ., ə, ., n, ᵻ, ˈ, z, aɪ, ., ə, ., k, ə ( grc-gre, Διονυσιακά, ''Dionysiaká'') is an ancient Greek epic poem and the principal work of Nonnus. It is an epic in 48 books, the longest surv ...

'', "I have oracles of history on seven tablets, and the tablets bear the names of the seven planets."

Planets in the Middle Ages

Medieval and Renaissance writers generally accepted the idea of seven planets. The standard medieval introduction to astronomy,

Medieval and Renaissance writers generally accepted the idea of seven planets. The standard medieval introduction to astronomy, Sacrobosco

Johannes de Sacrobosco, also written Ioannes de Sacro Bosco, later called John of Holywood or John of Holybush ( 1195 – 1256), was a scholar, monk, and astronomer who taught at the University of Paris.

He wrote a short introduction to the Hi ...

's '' De Sphaera'', includes the Sun and Moon among the planets, the more advanced ''Theorica planetarum'' presents the "theory of the seven planets," while the instructions to the '' Alfonsine Tables'' show how "to find by means of tables the mean ''motuses'' of the sun, moon, and the rest of the planets." In his ''Confessio Amantis

''Confessio Amantis'' ("The Lover's Confession") is a 33,000-line Middle English poem by John Gower, which uses the confession made by an ageing lover to the chaplain of Venus as a frame story for a collection of shorter narrative poems. Acco ...

'', 14th-century poet John Gower

John Gower (; c. 1330 – October 1408) was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and the Pearl Poet, and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is remembered primarily for three major works, the '' Mirour de l'Omme'', '' Vo ...

, referring to the planets' connection with the craft of alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim wo ...

, writes, "Of the planetes ben begonne/The gold is tilted to the Sonne/The Mone of Selver hath his part...", indicating that the Sun and the Moon were planets. Even Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

, who rejected the geocentric model, was ambivalent concerning whether the Sun and Moon were planets. In his ''De Revolutionibus

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

'', Copernicus clearly separates "the sun, moon, planets and stars"; however, in his Dedication of the work to Pope Paul III, Copernicus refers to, "the motion of the sun and the moon... and of the five other planets."

Earth

Eventually, when Copernicus's

Eventually, when Copernicus's heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

was accepted over the geocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

, Earth was placed among the planets and the Sun and Moon were reclassified, necessitating a conceptual revolution in the understanding of planets. As the historian of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopo ...

Thomas Kuhn

Thomas Samuel Kuhn (; July 18, 1922 – June 17, 1996) was an American philosopher of science whose 1962 book '' The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' was influential in both academic and popular circles, introducing the term ''paradig ...

noted in his book, ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' (1962; second edition 1970; third edition 1996; fourth edition 2012) is a book about the history of science by philosopher Thomas S. Kuhn. Its publication was a landmark event in the history, philoso ...

'':

The Copernicans who denied its traditional title 'planet' to the sun ... were changing the meaning of 'planet' so that it would continue to make useful distinctions in a world where all celestial bodies ... were seen differently from the way they had been seen before... Looking at the moon, the convert to Copernicanism ... says, 'I once took the moon to be (or saw the moon as) a planet, but I was mistaken.'Copernicus obliquely refers to Earth as a planet in ''De Revolutionibus'' when he says, "Having thus assumed the motions which I ascribe to the Earth later on in the volume, by long and intense study I finally found that if the motions of the other planets are correlated with the orbiting of the earth..."

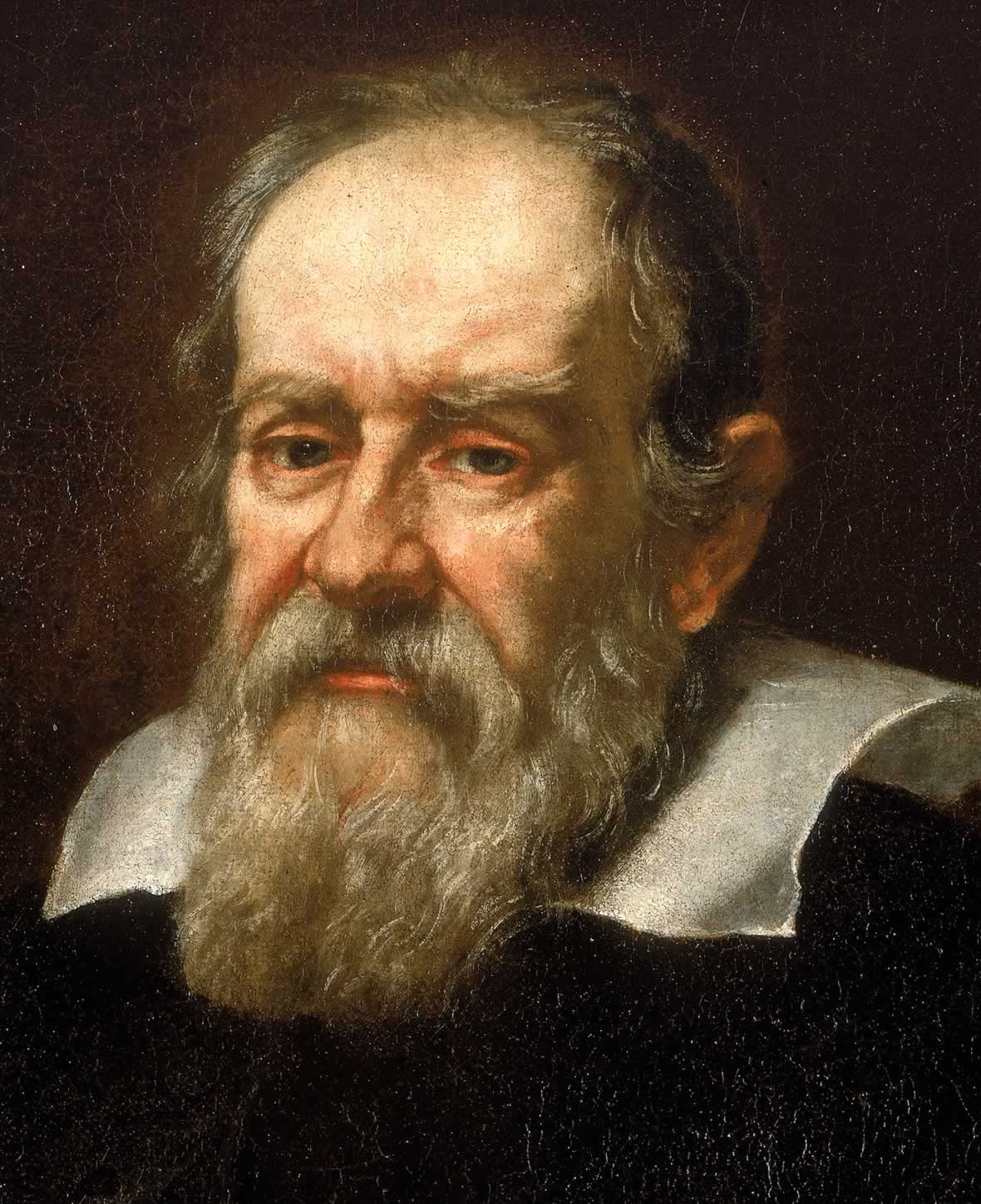

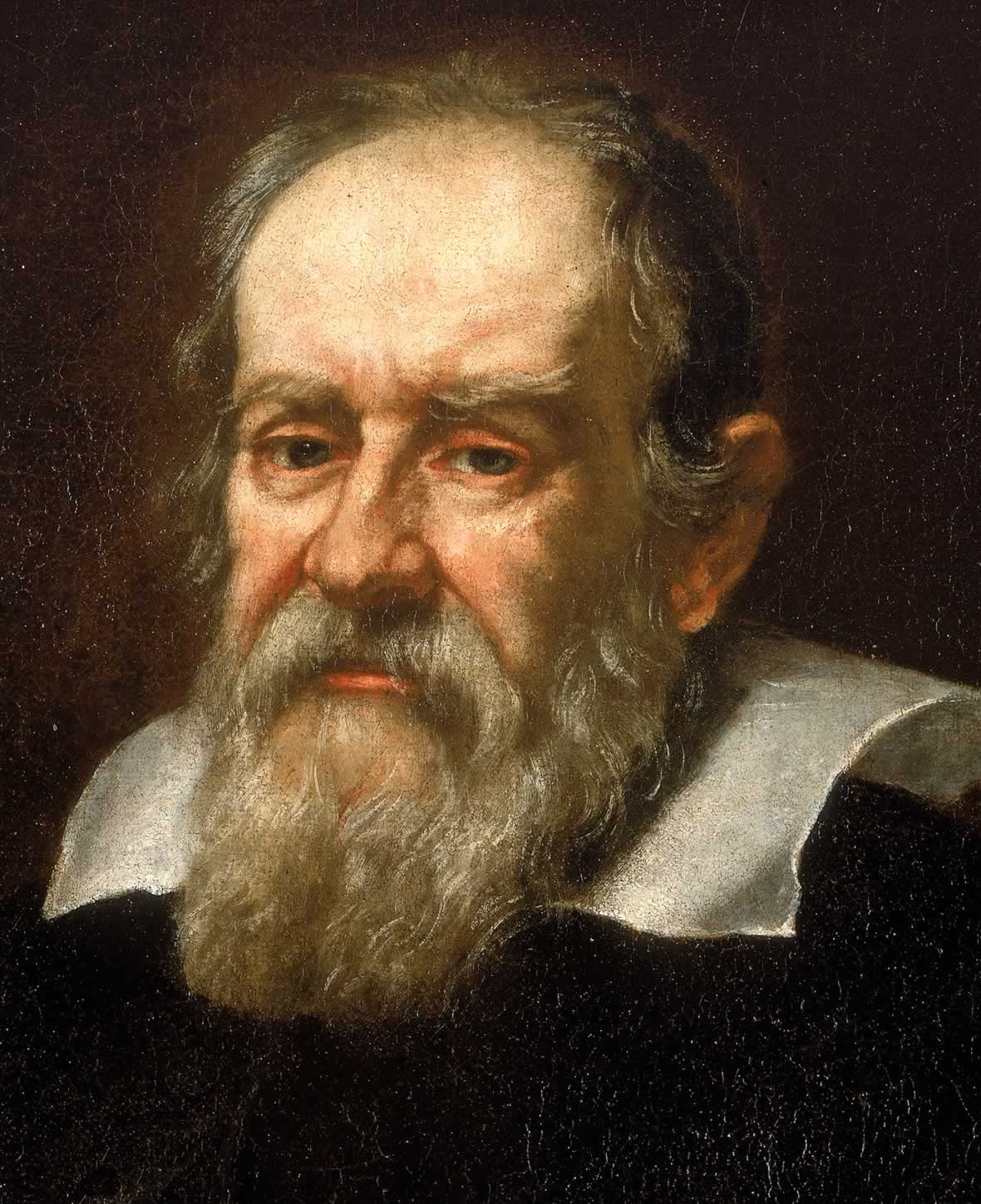

Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

also asserts that Earth is a planet in the ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

The ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 Italian-language book by Galileo Galilei comparing the Copernican system with the traditional Ptolemaic system. It was tran ...

'': " e Earth, no less than the moon or any other planet, is to be numbered among the natural bodies that move circularly."

Modern planets

In 1781, the astronomer

In 1781, the astronomer William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline ...

was searching the sky for elusive stellar parallax

Stellar parallax is the apparent shift of position of any nearby star (or other object) against the background of distant objects, and a basis for determining (through trigonometry) the distance of the object. Created by the different orbital p ...

es, when he observed what he termed a comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ...

in the constellation of Taurus. Unlike stars, which remained mere points of light even under high magnification, this object's size increased in proportion to the power used. That this strange object might have been a planet simply did not occur to Herschel; the five planets beyond Earth had been part of humanity's conception of the universe since antiquity. As the asteroids had yet to be discovered, comets were the only moving objects one expected to find in a telescope. However, unlike a comet, this object's orbit was nearly circular and within the ecliptic plane. Before Herschel announced his discovery of his "comet", his colleague, British Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834.

The post ...

Nevil Maskelyne

Nevil Maskelyne (; 6 October 1732 – 9 February 1811) was the fifth British Astronomer Royal. He held the office from 1765 to 1811. He was the first person to scientifically measure the mass of the planet Earth. He created the ''British Nau ...

, wrote to him, saying, "I don't know what to call it. It is as likely to be a regular planet moving in an orbit nearly circular to the sun as a Comet moving in a very eccentric ellipsis. I have not yet seen any coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

or tail to it." The "comet" was also very far away, too far away for a mere comet to resolve itself. Eventually it was recognised as the seventh planet and named Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus ( Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars), grandfather of Zeus (Jupiter) and father of ...

after the father of Saturn.

Gravitationally induced irregularities in Uranus's observed orbit led eventually to the discovery of Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 time ...

in 1846, and presumed irregularities in Neptune's orbit subsequently led to a search which did not find the perturbing object (it was later found to be a mathematical artefact caused by an overestimation of Neptune's mass) but did find Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

in 1930. Initially believed to be roughly the mass of the Earth, observation gradually shrank Pluto's estimated mass until it was revealed to be a mere five hundredth as large; far too small to have influenced Neptune's orbit at all.

In 1989, Voyager 2

''Voyager 2'' is a space probe launched by NASA on August 20, 1977, to study the outer planets and interstellar space beyond the Sun's heliosphere. As a part of the Voyager program, it was launched 16 days before its twin, '' Voyager 1'', ...

determined the irregularities to be due to an overestimation of Neptune's mass.

Satellites

When Copernicus placed Earth among the planets, he also placed the Moon in orbit around Earth, making the Moon the first

When Copernicus placed Earth among the planets, he also placed the Moon in orbit around Earth, making the Moon the first natural satellite

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moons'' ...

to be identified. When Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

discovered his four satellites

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotop ...

of Jupiter in 1610, they lent weight to Copernicus's argument, because if other planets could have satellites, then Earth could too. However, there remained some confusion as to whether these objects were "planets"; Galileo referred to them as "four planets flying around the star of Jupiter at unequal intervals and periods with wonderful swiftness." Similarly, Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

, upon discovering Saturn's largest moon Titan

Titan most often refers to:

* Titan (moon), the largest moon of Saturn

* Titans, a race of deities in Greek mythology

Titan or Titans may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Fictional entities

Fictional locations

* Titan in fiction, fictiona ...

in 1655, employed many terms to describe it, including "planeta" (planet), "stella" (star), "luna" (moon), and "satellite" (attendant), a word coined by Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

. Giovanni Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini, also known as Jean-Dominique Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian (naturalised French) mathematician, astronomer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the ...

, in announcing his discovery of Saturn's moons Iapetus

In Greek mythology, Iapetus (; ; grc, Ἰαπετός, Iapetós), also Japetus, is a Titan, the son of Uranus and Gaia and father of Atlas (mythology), Atlas, Prometheus, Epimetheus (mythology), Epimetheus, and Menoetius (mythology), Menoetius. ...

and Rhea in 1671 and 1672, described them as ''Nouvelles Planetes autour de Saturne'' ("New planets around Saturn"). However, when the "Journal de Scavans" reported Cassini's discovery of two new Saturnian moons ( Dione and Tethys) in 1686, it referred to them strictly as "satellites", though sometimes Saturn as the "primary planet". When William Herschel announced his discovery of two objects in orbit around Uranus in 1787 ( Titania and Oberon

Oberon () is a king of the fairies in medieval and Renaissance literature. He is best known as a character in William Shakespeare's play ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', in which he is King of the Fairies and spouse of Titania, Queen of the Fairi ...

), he referred to them as "satellites" and "secondary planets". All subsequent reports of natural satellite discoveries used the term "satellite" exclusively, though the 1868 book "Smith's Illustrated Astronomy" referred to satellites as "secondary planets".

Minor planets

One of the unexpected results of

One of the unexpected results of William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline ...

's discovery of Uranus was that it appeared to validate Bode's law, a mathematical function which generates the size of the semimajor axis

In geometry, the major axis of an ellipse is its longest diameter: a line segment that runs through the center and both foci, with ends at the two most widely separated points of the perimeter. The semi-major axis (major semiaxis) is the lo ...

of planetary orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

s. Astronomers had considered the "law" a meaningless coincidence, but Uranus fell at very nearly the exact distance it predicted. Since Bode's law also predicted a body between Mars and Jupiter that at that point had not been observed, astronomers turned their attention to that region in the hope that it might be vindicated again. Finally, in 1801, astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi

Giuseppe Piazzi ( , ; 16 July 1746 – 22 July 1826) was an Italian Catholic priest of the Theatine order, mathematician, and astronomer. He established an observatory at Palermo, now the '' Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo – Giuseppe S ...

found a miniature new world, Ceres, lying at just the correct point in space. The object was hailed as a new planet.

Then in 1802, Heinrich Olbers discovered Pallas

Pallas may refer to:

Astronomy

* 2 Pallas asteroid

** Pallas family, a group of asteroids that includes 2 Pallas

* Pallas (crater), a crater on Earth's moon

Mythology

* Pallas (Giant), a son of Uranus and Gaia, killed and flayed by Athena

* Pa ...

, a second "planet" at roughly the same distance from the Sun as Ceres. That two planets could occupy the same orbit was an affront to centuries of thinking; even Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

had ridiculed the idea ("Two stars keep not their motion in one sphere"). Even so, in 1804, another world, Juno, was discovered in a similar orbit. In 1807, Olbers discovered a fourth object, Vesta, at a similar orbital distance.

Herschel suggested that these four worlds be given their own separate classification, asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere. ...

s (meaning "starlike" since they were too small for their disks to resolve and thus resembled star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

s), though most astronomers preferred to refer to them as planets. This conception was entrenched by the fact that, due to the difficulty of distinguishing asteroids from yet-uncharted stars, those four remained the only asteroids known until 1845. Science textbooks in 1828, after Herschel's death, still numbered the asteroids among the planets. With the arrival of more refined star charts, the search for asteroids resumed, and a fifth and sixth were discovered by Karl Ludwig Hencke

Karl Ludwig Hencke (8 April 1793 – 21 September 1866) was a German amateur astronomer and discoverer of minor planets. He is sometimes confused with Johann Franz Encke, another German astronomer.

Biography

Hencke was born in Driesen, Branden ...

in 1845 and 1847. By 1851 the number of asteroids had increased to 15, and a new method of classifying them, by affixing a number before their names in order of discovery, was adopted, inadvertently placing them in their own distinct category. Ceres became "(1) Ceres", Pallas became "(2) Pallas", and so on. By the 1860s, the number of known asteroids had increased to over a hundred, and observatories in Europe and the United States began referring to them collectively as "minor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

s", or "small planets", though it took the first four asteroids longer to be grouped as such. To this day, "minor planet" remains the official designation for all small bodies in orbit around the Sun, and each new discovery is numbered accordingly in the IAU's Minor Planet Catalogue

The following is a list of numbered minor planets in ascending numerical order. With the exception of comets, minor planets are all Small Solar System bodies, small bodies in the Solar System, including asteroids, Distant minor planet, distant o ...

.

Pluto

The long road from planethood to reconsideration undergone by Ceres is mirrored in the story of

The long road from planethood to reconsideration undergone by Ceres is mirrored in the story of Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

, which was named a planet soon after its discovery by Clyde Tombaugh

Clyde William Tombaugh (February 4, 1906 January 17, 1997) was an American astronomer. He discovered Pluto in 1930, the first object to be discovered in what would later be identified as the Kuiper belt. At the time of discovery, Pluto was cons ...

in 1930. Uranus and Neptune had been declared planets based on their circular orbits, large masses and proximity to the ecliptic plane. None of these applied to Pluto, a tiny and icy world in a region of gas giant

A gas giant is a giant planet composed mainly of hydrogen and helium. Gas giants are also called failed stars because they contain the same basic elements as a star. Jupiter and Saturn are the gas giants of the Solar System. The term "gas giant" ...

s with an orbit that carried it high above the ecliptic

The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of the Earth around the Sun. From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Sun's movement around the celestial sphere over the course of a year traces out a path along the ecliptic agains ...

and even inside that of Neptune. In 1978, astronomers discovered Pluto's largest moon, Charon

In Greek mythology, Charon or Kharon (; grc, Χάρων) is a psychopomp, the ferryman of Hades, the Greek underworld. He carries the souls of those who have been given funeral rites across the rivers Acheron and Styx, which separate the ...

, which allowed them to determine its mass. Pluto was found to be much tinier than anyone had expected: only one-sixth the mass of Earth's Moon. However, as far as anyone could yet tell, it was unique. Then, beginning in 1992, astronomers began to detect large numbers of icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune that were similar to Pluto in composition, size, and orbital characteristics. They concluded that they had discovered the long-hypothesised Kuiper belt

The Kuiper belt () is a circumstellar disc in the outer Solar System, extending from the orbit of Neptune at 30 astronomical units (AU) to approximately 50 AU from the Sun. It is similar to the asteroid belt, but is far larger—20 tim ...

(sometimes called the Edgeworth–Kuiper belt), a band of icy debris that is the source for "short-period" comets—those with orbital periods of up to 200 years.

Pluto's orbit lay within this band and thus its planetary status was thrown into question. Many scientists concluded that tiny Pluto should be reclassified as a minor planet, just as Ceres had been a century earlier. Mike Brown of the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

suggested that a "planet" should be redefined as "any body in the Solar System that is more massive than the total mass of all of the other bodies in a similar orbit." Those objects under that mass limit would become minor planets. In 1999, Brian G. Marsden

Brian Geoffrey Marsden (5 August 1937 – 18 November 2010) was a British astronomer and the longtime director of the Minor Planet Center (MPC) at the Center for Astrophysics Harvard & Smithsonian (director emeritus from 2006 to 2010).

...

of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

's Minor Planet Center

The Minor Planet Center (MPC) is the official body for observing and reporting on minor planets under the auspices of the International Astronomical Union (IAU). Founded in 1947, it operates at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

Function

T ...

suggested that Pluto be given the minor planet number 10000 while still retaining its official position as a planet. The prospect of Pluto's "demotion" created a public outcry, and in response the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

clarified that it was not at that time proposing to remove Pluto from the planet list.

The discovery of several other trans-Neptunian object

A trans-Neptunian object (TNO), also written transneptunian object, is any minor planet in the Solar System that orbits the Sun at a greater average distance than Neptune, which has a semi-major axis of 30.1 astronomical units (au).

Typically ...

s, such as Quaoar

Quaoar (50000 Quaoar), provisional designation , is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a region of icy planetesimals beyond Neptune. A non-resonant object ( cubewano), it measures approximately in diameter, about half the diameter of Pluto. Th ...

and Sedna, continued to erode arguments that Pluto was exceptional from the rest of the trans-Neptunian population. On July 29, 2005, Mike Brown and his team announced the discovery of a trans-Neptunian object confirmed to be more massive than Pluto, named Eris.

In the immediate aftermath of the object's discovery, there was much discussion as to whether it could be termed a " tenth planet". NASA even put out a press release describing it as such. However, acceptance of Eris as the tenth planet implicitly demanded a definition of planet that set Pluto as an arbitrary minimum size. Many astronomers, claiming that the definition of planet was of little scientific importance, preferred to recognise Pluto's historical identity as a planet by " grandfathering" it into the planet list.

IAU definition

The discovery of Eris forced the IAU to act on a definition. In October 2005, a group of 19 IAU members, which had already been working on a definition since the discovery of Sedna in 2003, narrowed their choices to a shortlist of three, usingapproval voting

Approval voting is an electoral system in which voters can select many candidates instead of selecting only one candidate.

Description

Approval voting ballots show a list of the options of candidates running. Approval voting lets each voter i ...

. The definitions were:

* A planet is any object in

* A planet is any object in orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

around the Sun with a diameter greater than 2,000 km. (eleven votes in favour)

* A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun whose shape is stable due to its own gravity. (eight votes in favour)

* A planet is any object in orbit around the Sun that is dominant in its immediate neighbourhood. (six votes in favour)

Since no consensus could be reached, the committee decided to put these three definitions to a wider vote at the IAU General Assembly meeting in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

in August 2006, and on August 24, the IAU put a final draft to a vote, which combined elements from two of the three proposals. It essentially created a medial classification between ''planet'' and ''rock'' (or, in the new parlance, ''small Solar System body

A small Solar System body (SSSB) is an object in the Solar System that is neither a planet, a dwarf planet, nor a natural satellite. The term was first defined in 2006 by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as follows: "All other obje ...

''), called ''dwarf planet

A dwarf planet is a small planetary-mass object that is in direct orbit of the Sun, smaller than any of the eight classical planets but still a world in its own right. The prototypical dwarf planet is Pluto. The interest of dwarf planets to ...

'' and placed Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

in it, along with Ceres and Eris. The vote was passed, with 424 astronomers taking part in the ballot.orig link

) The IAU also resolved that "''planets'' and ''dwarf planets'' are two distinct classes of objects", meaning that dwarf planets, despite their name, would not be considered planets. On September 13, 2006, the IAU placed Eris, its moon Dysnomia, and Pluto into their

Minor Planet Catalogue

The following is a list of numbered minor planets in ascending numerical order. With the exception of comets, minor planets are all Small Solar System bodies, small bodies in the Solar System, including asteroids, Distant minor planet, distant o ...

, giving them the official minor planet designations (134340) Pluto, (136199) Eris, and (136199) Eris I Dysnomia. Other possible dwarf planets

The number of dwarf planets in the Solar System is unknown. Estimates have run as high as 200 in the Kuiper belt and over 10,000 in the region beyond.

However, consideration of the surprisingly low densities of many large trans-Neptunian objec ...

, such as 2003 EL61, 2005 FY9, Sedna and Quaoar

Quaoar (50000 Quaoar), provisional designation , is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a region of icy planetesimals beyond Neptune. A non-resonant object ( cubewano), it measures approximately in diameter, about half the diameter of Pluto. Th ...

, were left in temporary limbo until a formal decision could be reached regarding their status.

On June 11, 2008, the IAU executive committee announced the establishment of a subclass of dwarf planets comprising the aforementioned "new category of trans-Neptunian objects" to which Pluto is a prototype. This new class of objects, termed plutoids, would include Pluto, Eris and any other trans-Neptunian dwarf planets, but excluded Ceres. The IAU decided that those TNOs with an absolute magnitude

Absolute magnitude () is a measure of the luminosity of a celestial object on an inverse logarithmic astronomical magnitude scale. An object's absolute magnitude is defined to be equal to the apparent magnitude that the object would have if it ...

brighter than +1 would be named by a joint commissions of the planetary and minor-planet naming committees, under the assumption that they were likely to be dwarf planets. To date, only two other TNOs, 2003 EL61 and 2005 FY9, have met the absolute magnitude requirement, while other possible dwarf planets, such as Sedna, Orcus and Quaoar, were named by the minor-planet committee alone. On July 11, 2008, the Working Group on Planetary Nomenclature named 2005 FY9 ''Makemake

Makemake (minor-planet designation 136472 Makemake) is a dwarf planet and – depending on how they are defined – the second-largest Kuiper belt object in the classical population, with a diameter approximately 60% that of Pluto. It h ...

'', and on September 17, 2008, they named 2003 EL61 ''Haumea

, discoverer =

, discovered =

, earliest_precovery_date = March 22, 1955

, mpc_name = (136108) Haumea

, pronounced =

, adjectives = Haumean

, note = yes

, alt_names =

, named_after = Haumea

, mp_category =

, orbit_ref =

, epoc ...

''.

Acceptance of the IAU definition

Among the most vocal proponents of the IAU's decided definition are Mike Brown, the discoverer of Eris;

Among the most vocal proponents of the IAU's decided definition are Mike Brown, the discoverer of Eris; Steven Soter

Steven Soter is an astrophysicist currently holding the positions of scientist-in-residence for New York University's Environmental Studies Program and of Research Associate for the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural Hi ...

, professor of astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 int ...

; and Neil deGrasse Tyson

Neil deGrasse Tyson ( or ; born October 5, 1958) is an American astrophysicist, author, and science communicator. Tyson studied at Harvard University, the University of Texas at Austin, and Columbia University. From 1991 to 1994, he was a p ...

, director of the Hayden Planetarium.

In the early 2000s, when the Hayden Planetarium was undergoing a $100 million renovation, Tyson refused to refer to Pluto as the ninth planet at the planetarium. He explained that he would rather group planets according to their commonalities rather than counting them. This decision resulted in Tyson receiving large amounts of hate mail, primarily from children. In 2009, Tyson The Pluto Files, wrote a book detailing the demotion of Pluto.

In an article in the January 2007 issue of ''Scientific American'', Soter cited the definition's incorporation of current theories of the formation and evolution of the Solar System; that as the earliest protoplanets emerged from the swirling dust of the protoplanetary disc, some bodies "won" the initial competition for limited material and, as they grew, their increased gravity meant that they accumulated more material, and thus grew larger, eventually outstripping the other bodies in the Solar System by a very wide margin. The asteroid belt, disturbed by the gravitational tug of nearby Jupiter, and the Kuiper belt, too widely spaced for its constituent objects to collect together before the end of the initial formation period, both failed to win the accretion competition.

When the numbers for the winning objects are compared to those of the losers, the contrast is striking; if Soter's concept that each planet occupies an "orbital zone" is accepted, then the least orbitally dominant planet, Mars, is larger than all other collected material in its orbital zone by a factor of 5100. Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt, only accounts for one third of the material in its orbit; Pluto's ratio is even lower, at around 7 percent. Mike Brown asserts that this massive difference in orbital dominance leaves "absolutely no room for doubt about which objects do and do not belong."

Ongoing controversies

Despite the IAU's declaration, a number of critics remain unconvinced. The definition is seen by some as arbitrary and confusing. A number ofPluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

-as-planet proponents, in particular Alan Stern, head of NASA's ''New Horizons'' mission to Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

, have circulated a petition among astronomers to alter the definition. Stern's claim is that, since less than 5 percent of astronomers voted for it, the decision was not representative of the entire astronomical community. Even with this controversy excluded, however, there remain several ambiguities in the definition.

Clearing the neighbourhood

One of the main points at issue is the precise meaning of "cleared the neighbourhood around itsorbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

". Alan Stern objects that "it is impossible and contrived to put a dividing line between dwarf planets and planets", and that since neither Earth, Mars, Jupiter, nor Neptune have entirely cleared their regions of debris, none could properly be considered planets under the IAU definition.

Mike Brown counters these claims by saying that, far from not having cleared their orbits, the major planets completely control the orbits of the other bodies within their orbital zone. Jupiter may coexist with a large number of small bodies in its orbit (the Trojan asteroids), but these bodies only exist in Jupiter's orbit because they are in the sway of the planet's huge gravity. Similarly, Pluto may cross the orbit of Neptune, but Neptune long ago locked Pluto and its attendant Kuiper belt objects, called plutinos, into a 3:2 resonance, i.e., they orbit the Sun twice for every three Neptune orbits. The orbits of these objects are entirely dictated by Neptune's gravity, and thus, Neptune is gravitationally dominant.

In October 2015, astronomer Jean-Luc Margot of the University of California Los Angeles proposed a metric for orbital zone clearance derived from whether an object can clear an orbital zone of extent 2 of its Hill radius in a specific time scale. This metric places a clear dividing line between the dwarf planets and the planets of the solar system. The calculation is based on the mass of the host star, the mass of the body, and the orbital period of the body. An Earth-mass body orbiting a solar-mass star clears its orbit at distances of up to 400 astronomical units from the star. A Mars-mass body at the orbit of Pluto clears its orbit. This metric, which leaves Pluto as a dwarf planet, applies to both the Solar System and to extrasolar systems.

Some opponents of the definition have claimed that "clearing the neighbourhood" is an ambiguous concept. Mark Sykes, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and organiser of the petition, expressed this opinion to National Public Radio. He believes that the definition does not categorise a planet by composition or formation, but, effectively, by its location. He believes that a Mars-sized or larger object beyond the orbit of Pluto would not be considered a planet, because he believes that it would not have time to clear its orbit.

Brown notes, however, that were the "clearing the neighbourhood" criterion to be abandoned, the number of planets in the Solar System could rise from eight to List of possible dwarf planets, more than 50, with hundreds more potentially to be discovered.

Mike Brown counters these claims by saying that, far from not having cleared their orbits, the major planets completely control the orbits of the other bodies within their orbital zone. Jupiter may coexist with a large number of small bodies in its orbit (the Trojan asteroids), but these bodies only exist in Jupiter's orbit because they are in the sway of the planet's huge gravity. Similarly, Pluto may cross the orbit of Neptune, but Neptune long ago locked Pluto and its attendant Kuiper belt objects, called plutinos, into a 3:2 resonance, i.e., they orbit the Sun twice for every three Neptune orbits. The orbits of these objects are entirely dictated by Neptune's gravity, and thus, Neptune is gravitationally dominant.