De Materia Medica on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(

Between 50 and 70 AD, a Greek physician in the Roman army,

Between 50 and 70 AD, a Greek physician in the Roman army,

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

name for the Greek work , , both meaning "On Medical Material") is a pharmacopoeia

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (from the obsolete typography ''pharmacopœia'', meaning "drug-making"), in its modern technical sense, is a book containing directions for the identification of compound medicines, and published by ...

of medicinal plants and the medicines

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy ( pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and re ...

that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

, a Greek physician in the Roman army. It was widely read for more than 1,500 years until supplanted by revised herbals in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, making it one of the longest-lasting of all natural history and pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

books.

The work describes many drugs known to be effective, including aconite, aloes

Agarwood, aloeswood, eaglewood or gharuwood is a fragrant dark resinous wood used in incense, perfume, and small carvings. This resinous wood is most commonly referred to as "Oud" or "Oudh". It is formed in the heartwood of aquilaria trees when ...

, colocynth, colchicum

''Colchicum'' ( or ) is a genus of perennial flowering plants containing around 160 species which grow from bulb-like corms. It is a member of the botanical family Colchicaceae, and is native to West Asia, Europe, parts of the Mediterranean coa ...

, henbane, opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy '' Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which ...

and squill

Squill is a common name for several lily-like plants and may refer to:

*''Drimia maritima'', medicinal plant native to the Mediterranean, formerly classified as ''Scilla maritima''

*''Scilla'', a genus of plants cultivated for their ornamental fl ...

. In all, about 600 plants are covered, along with some animals and mineral substances, and around 1000 medicines made from them.

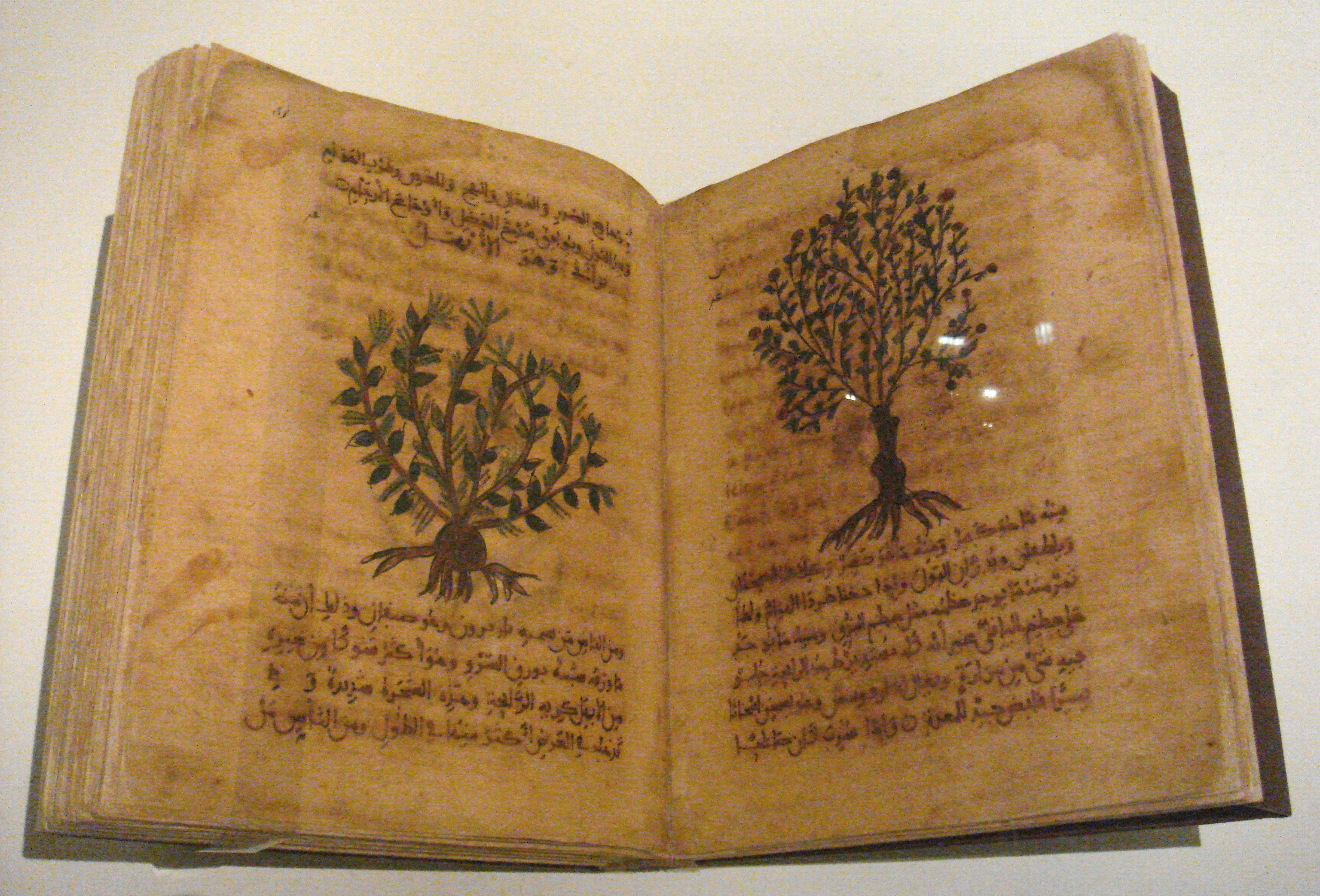

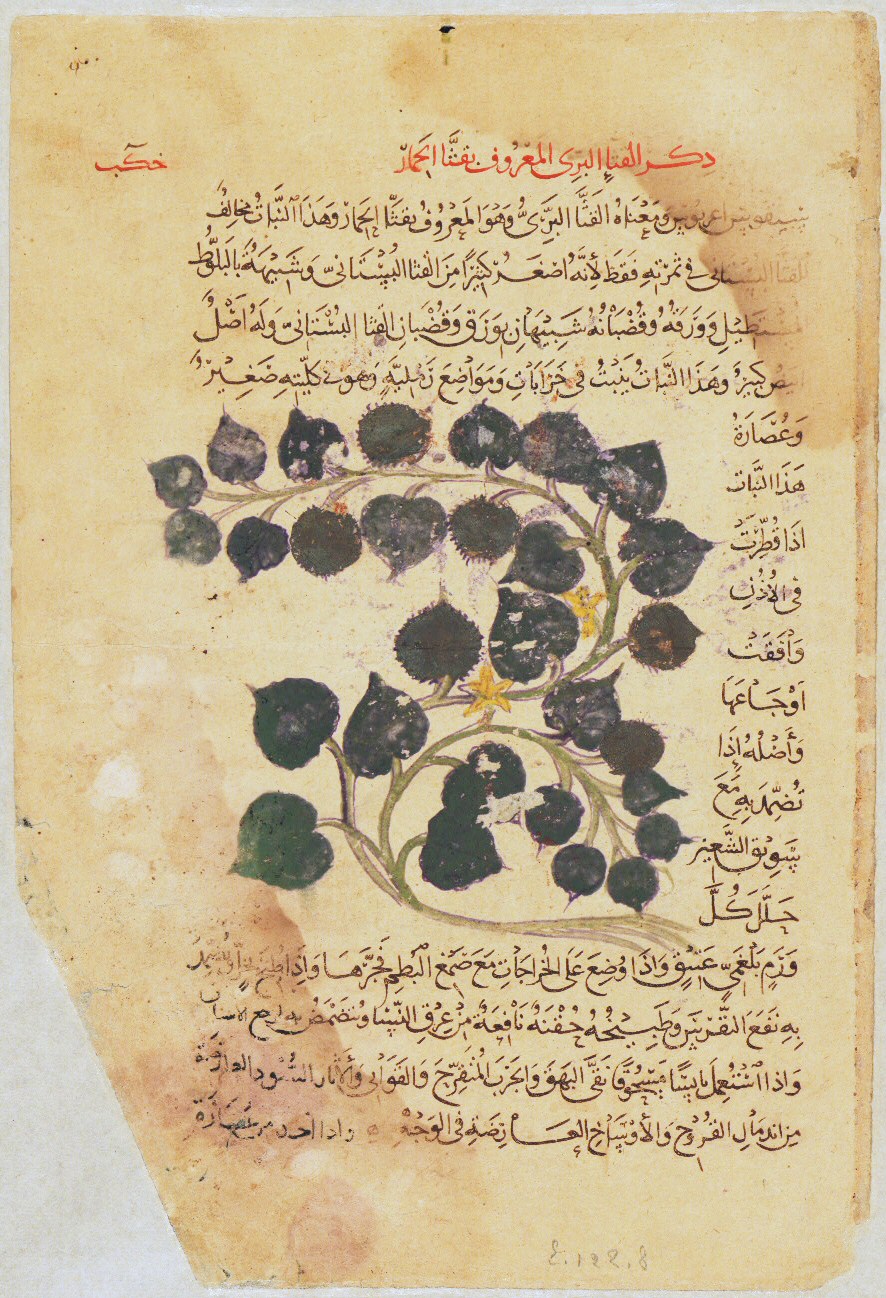

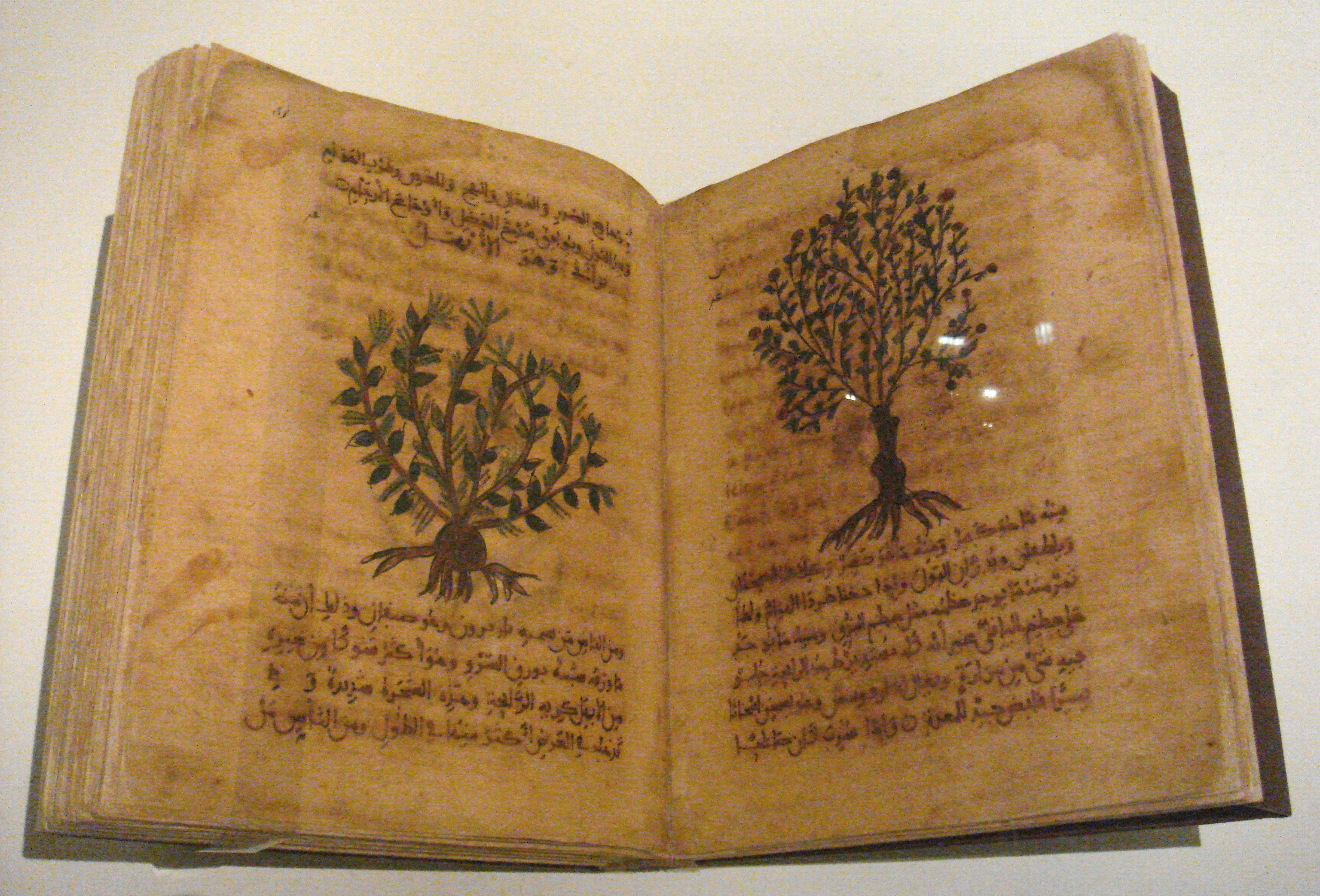

was circulated as illustrated manuscripts, copied by hand, in Greek, Latin and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

throughout the mediaeval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

period. From the 16th century on, Dioscorides' text was translated into Italian, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, Spanish, and French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, and in 1655 into English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

. It formed the basis for herbals in these languages by men such as Leonhart Fuchs

Leonhart Fuchs (; 17 January 1501 – 10 May 1566), sometimes spelled Leonhard Fuchs and cited in Latin as ''Leonhartus Fuchsius'', was a German physician and botanist. His chief notability is as the author of a large book about plants and th ...

, Valerius Cordus

Valerius Cordus (18 February 1515 – 25 September 1544) was a German physician, botanist and pharmacologist who authored the first pharmacopoeia North of the Alps and one of the most celebrated herbals in history. He is also widely credited ...

, Lobelius, Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Clusius, John Gerard

John Gerard (also John Gerarde, c. 1545–1612) was an English herbalist with a large garden in Holborn, now part of London. His 1,484-page illustrated ''Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes'', first published in 1597, became a popular gar ...

and William Turner. Gradually these herbals included more and more direct observations, supplementing and eventually supplanting the classical text.

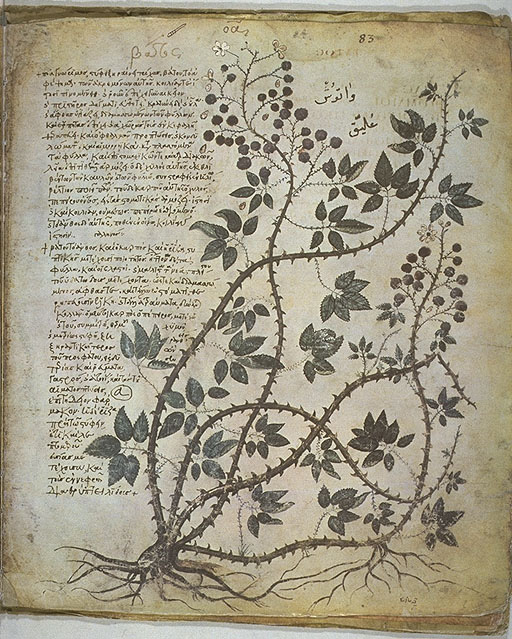

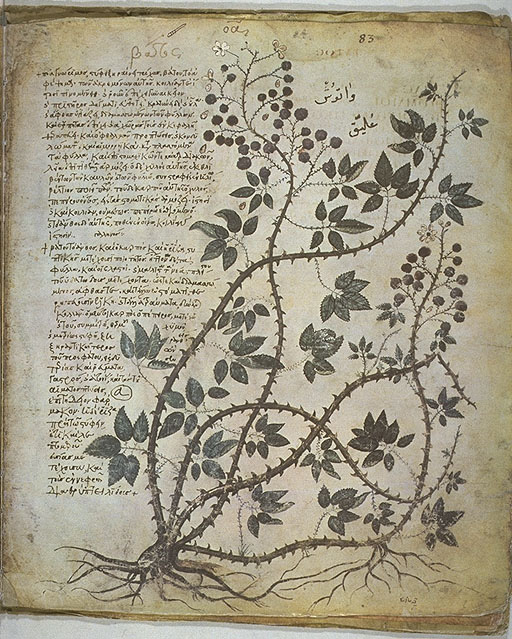

Several manuscripts and early printed versions of survive, including the illustrated Vienna Dioscurides

The Vienna Dioscurides or Vienna Dioscorides is an early 6th-century Byzantine Greek illuminated manuscript of an even earlier 1st century AD work, '' De materia medica'' (Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς : Perì hylēs iatrikēs in the ori ...

manuscript written in the original Greek in 6th-century Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

; it was used there by the Byzantines as a hospital text for just over a thousand years. Sir Arthur Hill saw a monk on Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; el, Ἄθως, ) is a mountain in the distal part of the eponymous Athos peninsula and site of an important centre of Eastern Orthodox monasticism in northeastern Greece. The mountain along with the respective part of the peni ...

still using a copy of Dioscorides to identify plants in 1934.

Book

Between 50 and 70 AD, a Greek physician in the Roman army,

Between 50 and 70 AD, a Greek physician in the Roman army, Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

, wrote a five-volume book in his native Greek, (, "On Medical Material"), known more widely in Western Europe by its Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

title . He had studied pharmacology at Tarsus in Roman Anatolia (now Turkey). The book became the principal reference work on pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

across Europe and the Middle East for over 1,500 years, and was thus the precursor of all modern pharmacopoeia

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (from the obsolete typography ''pharmacopœia'', meaning "drug-making"), in its modern technical sense, is a book containing directions for the identification of compound medicines, and published by ...

s.

In contrast to many classical authors, was not "rediscovered" in the Renaissance, because it never left circulation; indeed, Dioscorides' text eclipsed the Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: ''Corpus Hippocraticum''), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus cov ...

. In the medieval period, was circulated in Latin, Greek, and Arabic. In the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

from 1478 onwards, it was printed in Italian, German, Spanish, and French as well. In 1655, John Goodyer made an English translation from a printed version, probably not corrected from the Greek.

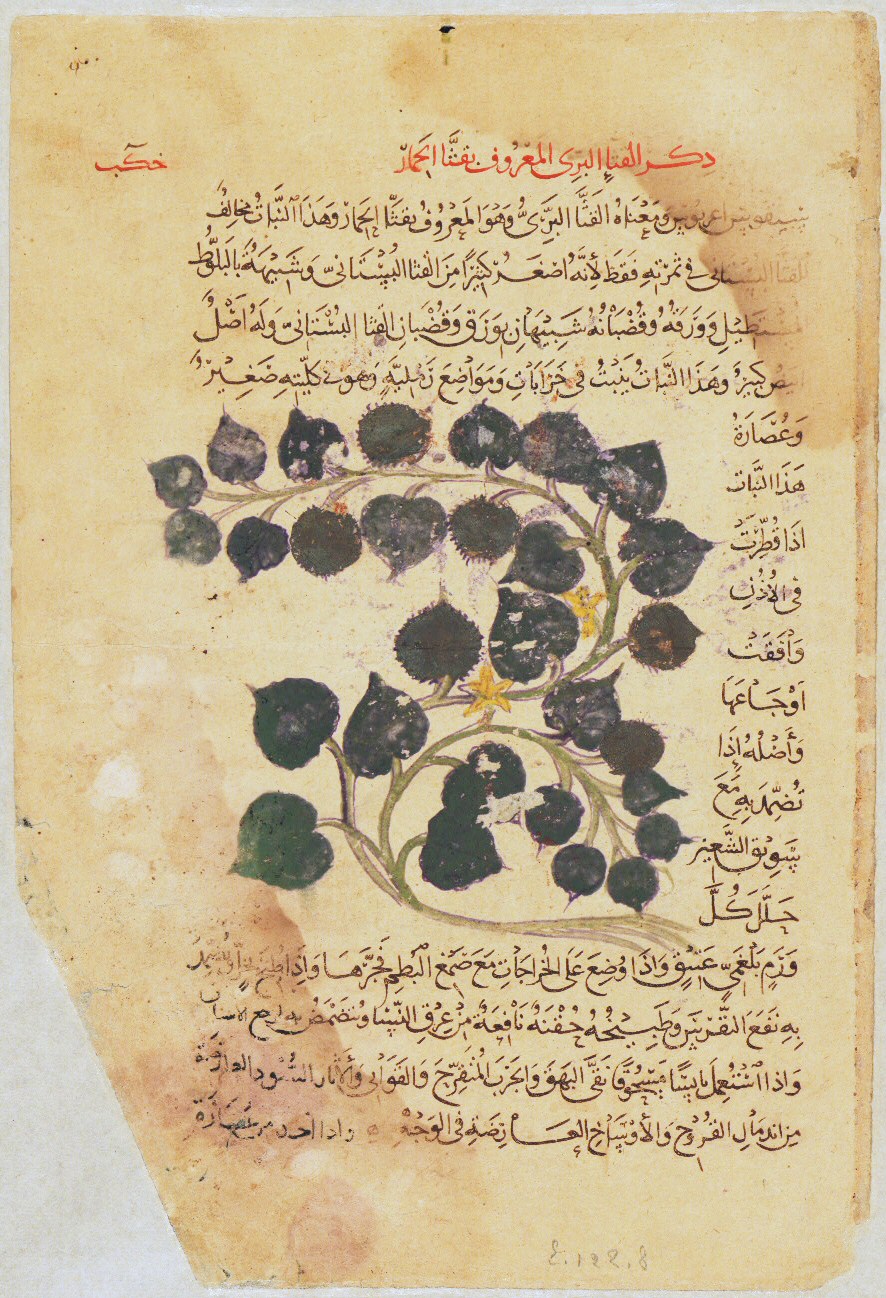

While being reproduced in manuscript form through the centuries, the text was often supplemented with commentary and minor additions from Arabic and Indian sources. Several illustrated manuscripts of survive. The most famous is the lavishly illustrated ''Vienna Dioscurides

The Vienna Dioscurides or Vienna Dioscorides is an early 6th-century Byzantine Greek illuminated manuscript of an even earlier 1st century AD work, '' De materia medica'' (Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς : Perì hylēs iatrikēs in the ori ...

'' (the ''Juliana Anicia Codex''), written in the original Greek in Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

Constantinople in 512/513 AD; its illustrations are sufficiently accurate to permit identification, something not possible with later medieval drawings of plants; some of them may be copied from a lost volume owned by Juliana Anicia's great grandfather, Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

, in the early 5th century. The '' Naples Dioscurides'' and '' Morgan Dioscurides'' are somewhat later Byzantine manuscripts in Greek, while other Greek manuscripts survive today in the monasteries of Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; el, Ἄθως, ) is a mountain in the distal part of the eponymous Athos peninsula and site of an important centre of Eastern Orthodox monasticism in northeastern Greece. The mountain along with the respective part of the peni ...

. Densely-illustrated Arabic copies survive from the 12th and 13th centuries. The result is a complex set of relationships between manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

s, involving translation, copying errors, additions of text and illustrations, deletions, reworkings, and a combination of copying from one manuscript and correction from another.

is the prime historical source of information about the medicines

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy ( pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and re ...

used by the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

, Romans, and other cultures of antiquity. The work also records the Dacian names

This article is a non-exhaustive lists of names used by the Dacian people, who were among the inhabitants of Eastern Europe before and during the Roman Empire. Many hundreds of personal names and placenames are known from ancient sources, and th ...

for some plants, which otherwise would have been lost. The work presents about 600 medicinal plants in all, along with some animals and mineral substances, and around 1,000 medicines made from these sources. Botanists have not always found Dioscorides' plants easy to identify from his short descriptions, partly because he had naturally described plants and animals from southeastern Europe, whereas by the 16th century his book was in use all over Europe and across the Islamic world. This meant that people attempted to force a match between the plants they knew and those described by Dioscorides, leading to what could be catastrophic results.

Approach

Each entry gives a substantial amount of detail on the plant or substance in question, concentrating on medicinal uses but giving such mention of other uses (such as culinary) and help with recognition as considered necessary. For example, on the "Mekon Agrios and Mekon Emeros", theopium poppy

''Papaver somniferum'', commonly known as the opium poppy or breadseed poppy, is a species of flowering plant in the family Papaveraceae. It is the species of plant from which both opium and poppy seeds are derived and is also a valuable ornam ...

and related species, Dioscorides states that the seed of one is made into bread: it has "a somewhat long little head and white seed", while another "has a head bending down" and a third is "more wild, more medicinal and longer than these, with a head somewhat long — and they are all cooling." After this brief description, he moves at once into pharmacology, saying that they cause sleep; other uses are to treat inflammation and erysipela, and if boiled with honey to make a cough mixture. The account thus combines recognition, pharmacological effect, and guidance on drug preparation. Its effects are summarized, accompanied by a caution:

Dioscorides then describes how to tell a good from a counterfeit preparation. He mentions the recommendations of other physicians, Diagoras (according to Eristratus), Andreas, and Mnesidemus, only to dismiss them as false and not borne out by experience. He ends with a description of how the liquid is gathered from poppy plants, and lists names used for it: ''chamaesyce'', ''mecon'' ''rhoeas'', ''oxytonon''; ''papaver'' to the Romans, and ''wanti'' to the Egyptians.

As late as in the Tudor and Stuart periods in Britain, herbals often still classified plants in the same way as Dioscorides and other classical authors, not by their structure or apparent relatedness but by how they smelt and tasted, whether they were edible, and what medicinal uses they had. Only when European botanists like Matthias de l'Obel

Mathias de l'Obel, Mathias de Lobel or Matthaeus Lobelius (1538 – 3 March 1616) was a Flemish physician and plant enthusiast who was born in Lille, Flanders, in what is now Hauts-de-France, France, and died at Highgate, London, Engla ...

, Andrea Cesalpino

Andrea Cesalpino ( Latinized as Andreas Cæsalpinus) (6 June 1524 – 23 February 1603) was a Florentine physician, philosopher and botanist.

In his works he classified plants according to their fruits and seeds, rather than alphabetically o ...

and Augustus Quirinus Rivinus (Bachmann) had done their best to match plants they knew to those listed in Dioscorides did they go further and create new classification systems Classification is a process related to categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated and understood.

Classification is the grouping of related facts into classes.

It may also refer to:

Business, organizat ...

based on similarity of parts, whether leaves, fruits, or flowers.

Contents

The book is divided into five volumes. Dioscorides organized the substances by certain similarities, such as their being aromatic, or vines; these divisions do not correspond to any modern classification. In David Sutton's view the grouping is by the type of effect on the human body.Volume I: Aromatics

Volume I covers aromatic oils, the plants that provide them, and ointments made from them. They include what are probablycardamom

Cardamom (), sometimes cardamon or cardamum, is a spice made from the seeds of several plants in the genera '' Elettaria'' and '' Amomum'' in the family Zingiberaceae. Both genera are native to the Indian subcontinent and Indonesia. They ar ...

, nard, valerian, cassia or senna, cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus '' Cinnamomum''. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, breakf ...

, balm of Gilead, hops

Hops are the flowers (also called seed cones or strobiles) of the hop plant '' Humulus lupulus'', a member of the Cannabaceae family of flowering plants. They are used primarily as a bittering, flavouring, and stability agent in beer, to w ...

, mastic, turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthene, terebinthine and (colloquially) turps) is a fluid obtained by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Mainly used as a special ...

, pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

resin, bitumen

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term a ...

, heather, quince

The quince (; ''Cydonia oblonga'') is the sole member of the genus ''Cydonia'' in the Malinae subtribe (which also contains apples and pears, among other fruits) of the Rosaceae family. It is a deciduous tree that bears hard, aromatic bright ...

, apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus '' Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancest ...

, peach

The peach (''Prunus persica'') is a deciduous tree first domesticated and cultivated in Zhejiang province of Eastern China. It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and others (the glossy-skinned, n ...

, apricot

An apricot (, ) is a fruit, or the tree that bears the fruit, of several species in the genus '' Prunus''.

Usually, an apricot is from the species '' P. armeniaca'', but the fruits of the other species in ''Prunus'' sect. ''Armeniaca'' are al ...

, lemon

The lemon (''Citrus limon'') is a species of small evergreen trees in the flowering plant family Rutaceae, native to Asia, primarily Northeast India (Assam), Northern Myanmar or China.

The tree's ellipsoidal yellow fruit is used for culin ...

, pear

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in the Northern Hemisphere in late summer into October. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus ''Pyrus'' , in the Family (biology), family Rosacea ...

, medlar, plum

A plum is a fruit of some species in ''Prunus'' subg. ''Prunus'.'' Dried plums are called prunes.

History

Plums may have been one of the first fruits domesticated by humans. Three of the most abundantly cultivated species are not found ...

and many others.

Volume II: Animals to herbs

Volume II covers an assortment of topics: animals including sea creatures such assea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) o ...

, seahorse

A seahorse (also written ''sea-horse'' and ''sea horse'') is any of 46 species of small marine fish in the genus ''Hippocampus''. "Hippocampus" comes from the Ancient Greek (), itself from () meaning "horse" and () meaning "sea monster" or ...

, whelk, mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other edible clams, which ...

, crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura, which typically have a very short projecting "tail" (abdomen) ( el, βραχύς , translit=brachys = short, / = tail), usually hidden entirely under the thorax. They live in all th ...

, scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always en ...

, electric ray, viper, cuttlefish

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of ...

and many others; dairy produce; cereals

A cereal is any grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran. Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more food ...

; vegetables such as sea kale

''Crambe maritima'', common name sea kale, seakale or crambe, is a species of halophytic (salt-tolerant) flowering plant in the genus '' Crambe'' of the family Brassicaceae. It grows wild along the coasts of mainland Europe and the British I ...

, beetroot

The beetroot is the taproot portion of a beet plant, usually known in North America as beets while the vegetable is referred to as beetroot in British English, and also known as the table beet, garden beet, red beet, dinner beet or golden bee ...

, asparagus; and sharp herbs such as garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plant in the genus '' Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chive, Welsh onion and Chinese onion. It is native to South Asia, Central Asia and northeas ...

, leek

The leek is a vegetable, a cultivar of '' Allium ampeloprasum'', the broadleaf wild leek ( syn. ''Allium porrum''). The edible part of the plant is a bundle of leaf sheaths that is sometimes erroneously called a stem or stalk. The genus '' Al ...

, onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' L., from Latin ''cepa'' meaning "onion"), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus '' Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the on ...

, caper

''Capparis spinosa'', the caper bush, also called Flinders rose, is a perennial plant that bears rounded, fleshy leaves and large white to pinkish-white flowers.

The plant is best known for the edible flower buds (capers), used as a seasoning ...

and mustard.

Volume III: Roots, seeds and herbs

Volume III covers roots, seeds and herbs. These include plants that may berhubarb

Rhubarb is the fleshy, edible stalks ( petioles) of species and hybrids (culinary rhubarb) of '' Rheum'' in the family Polygonaceae, which are cooked and used for food. The whole plant – a herbaceous perennial growing from short, thick rhi ...

, gentian, liquorice

Liquorice (British English) or licorice (American English) ( ; also ) is the common name of ''Glycyrrhiza glabra'', a flowering plant of the bean family Fabaceae, from the root of which a sweet, aromatic flavouring can be extracted.

The liqu ...

, caraway, cumin

Cumin ( or , or Article title

) (''Cuminum cyminum'') is a

Along with his fellow physicians of Ancient Rome, Aulus Cornelius Celsus,

Along with his fellow physicians of Ancient Rome, Aulus Cornelius Celsus,

The Dioscorides translator and editor Tess Anne Osbaldeston notes that "For almost two millennia Dioscorides was regarded as the ultimate authority on plants and medicine", and that he "achieved overwhelming commendation and approval because his writings addressed the many ills of mankind most usefully." To illustrate this, she states that "Dioscorides describes many valuable drugs including aconite,

The Dioscorides translator and editor Tess Anne Osbaldeston notes that "For almost two millennia Dioscorides was regarded as the ultimate authority on plants and medicine", and that he "achieved overwhelming commendation and approval because his writings addressed the many ills of mankind most usefully." To illustrate this, she states that "Dioscorides describes many valuable drugs including aconite,

Naples_Dioscurides

:_Codex_ex_Vindobonensis_Graecus_1_ca_500_AD,_at_Biblioteca_Nazionale_di_Napoli.html" ;"title="Naples Dioscurides">Naples Dioscurides

: Codex ex Vindobonensis Graecus 1 ca 500 AD, at Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli">Naples Dioscurides">Naples Dioscurides

: Codex ex Vindobonensis Graecus 1 ca 500 AD, at Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli site *

English description, World Digital Library

Edition of :de:Karl Gottlob Kühn, Karl Gottlob Kühn

, being Volume XXV of his ''Medicorum Graecorum Opera'', Leipzig 1829, together with annotation and parallel text in Latin] *

Book I

Book II

Book III

Book IV

Book V

Indices

* Edition of Max Wellman, Berlin *

Books I, II

-

Books III, IV

Book V

;Greek and Latin * (''Index in frontispiece'') ;Latin:

Edition_of_Jean_Ruel

_1552.html" ;"title="Jean Ruel">Edition of Jean Ruel

1552">Jean Ruel">Edition of Jean Ruel

1552*

Index

Preface

Book I

Book II

Book III

Book IV

Book V

* ''De Medica Materia : libri sex, Ioanne Ruellio Suesseionensi interprete'', translated by Jean Ruel (1546). * ''De Materia medica : libri V Eiusdem de Venenis Libri duo. Interprete Iano Antonio Saraceno Lugdunaeo, Medico'', translated by Janus Antonius Saracenus (1598). ;English: * ''The Greek Herbal of Dioscorides ... Englished by John Goodyer A. D. 1655'', edited by R.T. Gunter (1933). * ''De materia medica'', translated by Lily Y. Beck (2005). Hildesheim: Olms-Weidman. * (from the Latin, after John Goodyer 1655]) ;French:

Edition of Martin Mathee, Lyon (1559)

in six books ;German:

Edition of J Berendes, Stuttgart 1902

;Spanish:

Edition of Andres de Laguna 1570

site

Andres de Laguna, published at Antwerp 1555

at

Dioscórides Interactivo

Ediciones Universidad Salamanca. Spanish and Greek.

) (''Cuminum cyminum'') is a

parsley

Parsley, or garden parsley (''Petroselinum crispum'') is a species of flowering plant in the family Apiaceae that is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean region (Sardinia, Lebanon, Israel, Cyprus, Turkey, southern Italy, Greece, ...

, lovage, fennel

Fennel (''Foeniculum vulgare'') is a flowering plant species in the carrot family. It is a hardy, perennial herb with yellow flowers and feathery leaves. It is indigenous to the shores of the Mediterranean but has become widely naturalized ...

and many others.

Volume IV: Roots and herbs, continued

Volume IV describes further roots and herbs not covered in Volume III. These include herbs that may bebetony Betony is a common name for a plant which may refer to:

*''Stachys'', a genus of plants containing several species commonly known as betony in Europe

**''Stachys officinalis'', a historically important medicinal plant

*''Pedicularis

''Pediculari ...

, Solomon's seal, clematis, horsetail, daffodil

''Narcissus'' is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,The word "daffodil" is also applied to related genera such as '' Sternbergia'', ''Is ...

and many others.

Volume V: Vines, wines and minerals

Volume V covers the grapevine, wine made from it, grapes and raisins; but also strong medicinal potions made by boiling many other plants including mandrake, hellebore, and various metal compounds, such as what may be zinc oxide,verdigris

Verdigris is the common name for blue-green, copper-based pigments that form a patina on copper, bronze, and brass. The technical literature is ambiguous as to its chemical composition. Some sources refer to "neutral verdigris" as copper(II) ...

and iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of wh ...

.

Influence and effectiveness

Arabic medicine

Along with his fellow physicians of Ancient Rome, Aulus Cornelius Celsus,

Along with his fellow physicians of Ancient Rome, Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

, Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

and Soranus of Ephesus, Dioscorides had a major and long-lasting effect on Arabic medicine as well as medical practice across Europe. was one of the first scientific works to be translated from Greek into Arabic. It was translated first into Syriac and then into Arabic in 9th century Baghdad.

In Europe

Writing in ''The Great Naturalists'', the historian of science David Sutton describes as "one of the most enduring works of natural history ever written" and that "it formed the basis for Western knowledge of medicines for the next 1,500 years." The historian of science Marie Boas writes that herbalists depended entirely on Dioscorides andTheophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

until the 16th century, when they finally realized they could work on their own. She notes also that herbals by different authors, such as Leonhart Fuchs

Leonhart Fuchs (; 17 January 1501 – 10 May 1566), sometimes spelled Leonhard Fuchs and cited in Latin as ''Leonhartus Fuchsius'', was a German physician and botanist. His chief notability is as the author of a large book about plants and th ...

, Valerius Cordus

Valerius Cordus (18 February 1515 – 25 September 1544) was a German physician, botanist and pharmacologist who authored the first pharmacopoeia North of the Alps and one of the most celebrated herbals in history. He is also widely credited ...

, Lobelius, Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Clusius, John Gerard

John Gerard (also John Gerarde, c. 1545–1612) was an English herbalist with a large garden in Holborn, now part of London. His 1,484-page illustrated ''Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes'', first published in 1597, became a popular gar ...

and William Turner, were dominated by Dioscorides, his influence only gradually weakening as the 16th-century herbalists "learned to add and substitute their own observations".

Early science and medicine historian Paula Findlen, writing in the ''Cambridge History of Science'', calls "one of the most successful and enduring herbals of antiquity, hichemphasized the importance of understanding the natural world in light of its medicinal efficiency", in contrast to Pliny's '' Natural History'' (which emphasized the wonders of nature) or the natural history studies of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

(which emphasized the causes of natural phenomena). Medicine historian Vivian Nutton

Vivian Nutton FBA (born 21 December 1943) is a British historian of medicine who serves as Emeritus Professor at the UCL Centre for the History of Medicine, University College London, and current President of the Centre for the Study of Med ...

, in ''Ancient Medicine'', writes that Dioscorides's "five books in Greek On Materia medica attained canonical status in Late Antiquity." Science historian Brian Ogilvie calls Dioscorides "the greatest ancient herbalist", and "the ''summa'' of ancient descriptive botany", observing that its success was such that few other books in his domain have survived from classical times. Further, his approach matched the Renaissance liking for detailed description, unlike the philosophical search for essential nature (as in Theophrastus's ). A critical moment was the decision by Niccolò Leoniceno

Niccolò Leoniceno (1428–1524) was an Italian physician and humanist.

Biography

Leoniceno was born in Lonigo, Veneto, the son of a doctor.

He studied Greek in Vicenza under Ognibene da Lonigo (in Latin: ''Omnibonus Leonicenus'') (Lonigo, 1 ...

and others to use Dioscorides "as the model of the careful naturalist—and his book as the model for natural history."

The Dioscorides translator and editor Tess Anne Osbaldeston notes that "For almost two millennia Dioscorides was regarded as the ultimate authority on plants and medicine", and that he "achieved overwhelming commendation and approval because his writings addressed the many ills of mankind most usefully." To illustrate this, she states that "Dioscorides describes many valuable drugs including aconite,

The Dioscorides translator and editor Tess Anne Osbaldeston notes that "For almost two millennia Dioscorides was regarded as the ultimate authority on plants and medicine", and that he "achieved overwhelming commendation and approval because his writings addressed the many ills of mankind most usefully." To illustrate this, she states that "Dioscorides describes many valuable drugs including aconite, aloes

Agarwood, aloeswood, eaglewood or gharuwood is a fragrant dark resinous wood used in incense, perfume, and small carvings. This resinous wood is most commonly referred to as "Oud" or "Oudh". It is formed in the heartwood of aquilaria trees when ...

, bitter apple, colchicum

''Colchicum'' ( or ) is a genus of perennial flowering plants containing around 160 species which grow from bulb-like corms. It is a member of the botanical family Colchicaceae, and is native to West Asia, Europe, parts of the Mediterranean coa ...

, henbane, and squill

Squill is a common name for several lily-like plants and may refer to:

*''Drimia maritima'', medicinal plant native to the Mediterranean, formerly classified as ''Scilla maritima''

*''Scilla'', a genus of plants cultivated for their ornamental fl ...

". The work mentions the painkillers willow (leading ultimately to aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

, she writes), autumn crocus and opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy '' Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which ...

, which however is also narcotic. Many other substances that Dioscorides describes remain in modern pharmacopoeias as "minor drugs, diluents, flavouring agents, and emollients

A moisturizer, or emollient, is a cosmetic preparation used for protecting, moisturizing, and lubricating the skin. These functions are normally performed by sebum produced by healthy skin. The word "emollient" is derived from the Latin verb ''m ...

... uch as

Uch ( pa, ;

ur, ), frequently referred to as Uch Sharīf ( pa, ;

ur, ; ''"Noble Uch"''), is a historic city in the southern part of Pakistan's Punjab province. Uch may have been founded as Alexandria on the Indus, a town founded by Alexand ...

ammoniacum, anise

Anise (; '), also called aniseed or rarely anix is a flowering plant in the family Apiaceae native to Eurasia.

The flavor and aroma of its seeds have similarities with some other spices and herbs, such as star anise, fennel, licorice, and t ...

, cardamom

Cardamom (), sometimes cardamon or cardamum, is a spice made from the seeds of several plants in the genera '' Elettaria'' and '' Amomum'' in the family Zingiberaceae. Both genera are native to the Indian subcontinent and Indonesia. They ar ...

s, catechu

( or ) is an extract of acacia trees used variously as a food additive, astringent, tannin, and dye. It is extracted from several species of ''Acacia'', but especially ''Senegalia catechu'' (''Acacia catechu''), by boiling the wood in wate ...

, cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus '' Cinnamomum''. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, breakf ...

, colocynth, coriander

Coriander (;

, crocus

''Crocus'' (; plural: crocuses or croci) is a genus of seasonal flowering plants in the family Iridaceae (iris family) comprising about 100 species of perennials growing from corms. They are low growing plants, whose flower stems remain under ...

, dill, fennel

Fennel (''Foeniculum vulgare'') is a flowering plant species in the carrot family. It is a hardy, perennial herb with yellow flowers and feathery leaves. It is indigenous to the shores of the Mediterranean but has become widely naturalized ...

, galbanum, gentian, hemlock, hyoscyamus, lavender, linseed

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in W ...

, mastic, male fern, marjoram

Marjoram (; ''Origanum majorana'') is a cold-sensitive perennial herb or undershrub with sweet pine and citrus flavours. In some Middle Eastern countries, marjoram is synonymous with oregano, and there the names sweet marjoram and knotted marj ...

, marshmallow, mezereon

''Daphne mezereum'', commonly known as mezereum, mezereon, February daphne, spurge laurel or spurge olive, is a species of ''Daphne'' in the flowering plant family Thymelaeaceae, native to most of Europe and Western Asia, north to northern Scan ...

, mustard, myrrh

Myrrh (; from Semitic, but see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus '' Commiphora''. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine. Myrrh m ...

, orris (iris), oak gall

Oak apple or oak gall is the common name for a large, round, vaguely apple-like gall commonly found on many species of oak. Oak apples range in size from in diameter and are caused by chemicals injected by the larva of certain kinds of gall w ...

s, olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: ...

, pennyroyal, pepper, peppermint

Peppermint (''Mentha'' × ''piperita'') is a hybrid species of mint, a cross between watermint and spearmint. Indigenous to Europe and the Middle East, the plant is now widely spread and cultivated in many regions of the world.Euro+Med Plantb ...

, poppy, psyllium

Psyllium , or ispaghula , is the common name used for several members of the plant genus '' Plantago'' whose seeds are used commercially for the production of mucilage. Psyllium is mainly used as a dietary fiber to relieve symptoms of both const ...

, rhubarb

Rhubarb is the fleshy, edible stalks ( petioles) of species and hybrids (culinary rhubarb) of '' Rheum'' in the family Polygonaceae, which are cooked and used for food. The whole plant – a herbaceous perennial growing from short, thick rhi ...

, rosemary

''Salvia rosmarinus'' (), commonly known as rosemary, is a shrub with fragrant, evergreen, needle-like leaves and white, pink, purple, or blue flowers, native plant, native to the Mediterranean Region, Mediterranean region. Until 2017, it was kn ...

, rue, saffron

Saffron () is a spice derived from the flower of ''Crocus sativus'', commonly known as the "saffron crocus". The vivid crimson stigma (botany), stigma and stigma (botany)#style, styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly ...

, sesame

Sesame ( or ; ''Sesamum indicum'') is a flowering plant in the genus ''Sesamum'', also called benne. Numerous wild relatives occur in Africa and a smaller number in India. It is widely naturalized in tropical regions around the world and is cul ...

, squirting cucumber ( elaterium), starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human die ...

, stavesacre ( delphinium), storax, stramonium, sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

, terebinth

''Pistacia terebinthus'' also called the terebinth and the turpentine tree, is a deciduous tree species of the genus '' Pistacia'', native to the Mediterranean region from the western regions of Morocco and Portugal to Greece and western an ...

, thyme

Thyme () is the herb (dried aerial parts) of some members of the genus ''Thymus'' of aromatic perennial evergreen herbs in the mint family Lamiaceae. Thymes are relatives of the oregano genus '' Origanum'', with both plants being mostly indigen ...

, white hellebore, white horehound, and couch grass — the last still used as a demulcent diuretic

A diuretic () is any substance that promotes diuresis, the increased production of urine. This includes forced diuresis. A diuretic tablet is sometimes colloquially called a water tablet. There are several categories of diuretics. All diuretics i ...

." She notes that medicines such as wormwood, juniper

Junipers are coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Juniperus'' () of the cypress family Cupressaceae. Depending on the taxonomy, between 50 and 67 species of junipers are widely distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, from the Arc ...

, ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is a herbaceous perennial which grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of ...

, and calamine

Calamine, also known as calamine lotion, is a medication used to treat mild itchiness. This includes from sunburn, insect bites, poison ivy, poison oak, and other mild skin conditions. It may also help dry out skin irritation. It is applied ...

also remain in use, while " Chinese and Indian physicians continue to use liquorice

Liquorice (British English) or licorice (American English) ( ; also ) is the common name of ''Glycyrrhiza glabra'', a flowering plant of the bean family Fabaceae, from the root of which a sweet, aromatic flavouring can be extracted.

The liqu ...

". She observes that the many drugs listed to reduce the spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

may be explained by the frequency of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

in his time. Dioscorides lists drugs for women to cause abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

and to treat urinary tract infection

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection that affects part of the urinary tract. When it affects the lower urinary tract it is known as a bladder infection (cystitis) and when it affects the upper urinary tract it is known as a kidne ...

; palliative

Palliative care (derived from the Latin root , or 'to cloak') is an interdisciplinary medical caregiving approach aimed at optimizing quality of life and mitigating suffering among people with serious, complex, and often terminal illnesses. Wit ...

s for toothache, such as colocynth, and others for intestinal pains; and treatments for skin and eye diseases. As well as these useful substances, she observes that "A few superstitious practices are recorded in ," such as using '' Echium'' as an amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protect ...

to ward off snakes, or ''Polemonia'' ( Jacob's ladder) for scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always en ...

stings.

In the view of the historian Paula De Vos, formed the core of the European pharmacopoeia until the end of the 19th century, suggesting that "the timelessness of Dioscorides' work resulted from an empirical tradition based on trial and error; that it worked for generation after generation despite social and cultural changes and changes in medical theory".

At Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; el, Ἄθως, ) is a mountain in the distal part of the eponymous Athos peninsula and site of an important centre of Eastern Orthodox monasticism in northeastern Greece. The mountain along with the respective part of the peni ...

in northern Greece Dioscorides's text was still in use in its original Greek into the 20th century, as observed in 1934 by Sir Arthur Hill, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,100 ...

:

References

Bibliography

* * (subscription required for online access) * * * * * * * *Editions

''Note: Editions may vary by both text and numbering of chapters'' ;Greek:Naples_Dioscurides

:_Codex_ex_Vindobonensis_Graecus_1_ca_500_AD,_at_Biblioteca_Nazionale_di_Napoli.html" ;"title="Naples Dioscurides">Naples Dioscurides

: Codex ex Vindobonensis Graecus 1 ca 500 AD, at Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli">Naples Dioscurides">Naples Dioscurides

: Codex ex Vindobonensis Graecus 1 ca 500 AD, at Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli site *

English description, World Digital Library

Edition of :de:Karl Gottlob Kühn, Karl Gottlob Kühn

, being Volume XXV of his ''Medicorum Graecorum Opera'', Leipzig 1829, together with annotation and parallel text in Latin] *

Book I

Book II

Book III

Book IV

Book V

Indices

* Edition of Max Wellman, Berlin *

Books I, II

-

Books III, IV

Book V

;Greek and Latin * (''Index in frontispiece'') ;Latin:

Edition_of_Jean_Ruel

_1552.html" ;"title="Jean Ruel">Edition of Jean Ruel

1552">Jean Ruel">Edition of Jean Ruel

1552*

Index

Preface

Book I

Book II

Book III

Book IV

Book V

* ''De Medica Materia : libri sex, Ioanne Ruellio Suesseionensi interprete'', translated by Jean Ruel (1546). * ''De Materia medica : libri V Eiusdem de Venenis Libri duo. Interprete Iano Antonio Saraceno Lugdunaeo, Medico'', translated by Janus Antonius Saracenus (1598). ;English: * ''The Greek Herbal of Dioscorides ... Englished by John Goodyer A. D. 1655'', edited by R.T. Gunter (1933). * ''De materia medica'', translated by Lily Y. Beck (2005). Hildesheim: Olms-Weidman. * (from the Latin, after John Goodyer 1655]) ;French:

Edition of Martin Mathee, Lyon (1559)

in six books ;German:

Edition of J Berendes, Stuttgart 1902

;Spanish:

Edition of Andres de Laguna 1570

site

Andres de Laguna, published at Antwerp 1555

at

Biblioteca Nacional de España

The Biblioteca Nacional de España (''National Library of Spain'') is a major public library, the largest in Spain, and one of the largest in the world. It is located in Madrid, on the Paseo de Recoletos.

History

The library was founded by ...

site

Dioscórides Interactivo

Ediciones Universidad Salamanca. Spanish and Greek.

External links

{{Authority control Ancient Roman medicine Medical manuals Herbals History of pharmacy Natural history books Pharmacology literature Pharmacopoeias 1st-century Latin books