Duma Period on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the

Coming under pressure from the

Coming under pressure from the

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 ŌĆō 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 ŌĆō 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the

Speech from the Throne by Nicholas II at Opening of the State Duma, photo essay with commentary

Four Dumas of Imperial Russia

{{Authority control 1905 establishments in the Russian Empire 1917 disestablishments in Russia

lower house

A lower house is the lower chamber of a bicameral legislature, where the other chamber is the upper house. Although styled as "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has come to wield more power or otherwise e ...

of the legislature in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, while the upper house

An upper house is one of two Legislative chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house. The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restricted p ...

was the State Council State Council may refer to:

Government

* State Council of the People's Republic of China, the national cabinet and chief administrative authority of China, headed by the Premier

* State Council of the Republic of Korea, the national cabinet of S ...

. It held its meetings in the Tauride Palace

Tauride Palace () is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride commissioned his favourite architect, Ivan Starov, to design his city resi ...

in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

. It convened four times between 27 April 1906 and the collapse of the empire in February 1917. The first and the second dumas were more democratic and represented a greater number of national types than their successors. The third duma was dominated by gentry, landowners, and businessmen. The fourth duma held five sessions; it existed until 2 March 1917, and was formally dissolved on 6 October 1917.

History

Coming under pressure from the

Coming under pressure from the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, on August 6, 1905 (O.S.), Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (, ; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the emperor as head of government. Neither liberal nor conservative, he attracted ...

(appointed by Nicholas II

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. He married ...

to manage peace negotiations with Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

after the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 ŌĆō 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

of 1904ŌĆō1905) issued a manifesto about the convocation of the Duma, initially thought to be a purely advisory body, the so-called Bulygin

Alexander Grigoryevich Bulygin (; ŌĆō 5 September 1919) was the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, Minister of Interior of Russia from February 1905 until October 1905.

Biography

Graduate of the Imperial School of Jurisprudence, Imperial S ...

-Duma. In the subsequent October Manifesto

The October Manifesto (), officially "The Manifesto on the Improvement of the State Order" (), is a document that served as a precursor to the Russian Empire's first Constitution, which was adopted the following year in 1906. The Manifesto was is ...

, the emperor promised to introduce further civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

, provide for broad participation in a new "State Duma", and endow the Duma with legislative and oversight powers. The State Duma was to be the lower house

A lower house is the lower chamber of a bicameral legislature, where the other chamber is the upper house. Although styled as "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has come to wield more power or otherwise e ...

of a parliament, and the State Council of Imperial Russia

The State Council ( rus, ąōąŠčüčāą┤ą░╠üčĆčüčéą▓ąĄąĮąĮčŗą╣ čüąŠą▓ąĄ╠üčé, p=╔Ī╔Ös╩Ŗ╦łdarstv╩▓╔¬n(╦É)╔©j s╔É╦łv╩▓et) was the supreme state advisory body to the tsar in the Russian Empire. From 1906, it was the upper house of the parliament under t ...

the upper house

An upper house is one of two Legislative chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house. The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restricted p ...

.

However, Nicholas II was determined to retain his autocratic power (in which he succeeded). On April 23, 1906 ( O.S.), he issued the Fundamental Laws, which gave him the title of "supreme autocrat". Although no law could be made without the Duma's assent, neither could the Duma pass laws without the approval of the noble-dominated State Council (half of which was to be appointed directly by emperor), and the emperor himself retained a veto. The laws stipulated that ministers

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

could not be appointed by, and were not responsible to, the Duma, thus denying responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

at the executive level. Furthermore, Nicholas II had the power to dismiss the Duma and announce new elections whenever he wished; article 87 allowed him to pass temporary (emergency) laws by decrees. All these powers and prerogatives assured that, in practice, the Government of Russia continued to be a non-official absolute monarchy. It was in this context that the first Duma opened four days later, on April 27, 1906.

First Duma

The first Duma was established with around 500 deputies; most radical left parties, such as the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries and theRussian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

had boycotted the election, leaving the moderate Constitutional Democrats (Kadets) with the most deputies (around 184). Second came an alliance of slightly more radical leftists, the Trudoviks

The Trudoviks () were a democratic socialist political party of Russia in the early 20th century.

History

The Trudoviks were a breakaway of the Socialist Revolutionary Party faction as they defied the party's stance by standing in the First ...

(Laborites) with around 100 deputies. To the right of both were a number of smaller parties, including the Octobrists

The Union of 17 October (, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: ą×ą║čéčÅą▒čĆąĖčüčéčŗ, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in late Imperial Russia. It represent ...

. Together, they had around 45 deputies. Other deputies, mainly from peasant groups, were unaffiliated.

The Kadets were among the only political parties capable of consistently drawing voters due to their relatively moderate political stance. The Kadets drew from an especially urban population, often failing to draw the attention of rural communities who were instead committed to other parties.

The Duma ran for 73 days until 8 July 1906, with little success. The emperor and his loyal prime minister Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (; 8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 and again from 1914 to 1916, during World War I. He was the last person to have the civil rank ...

were keen to keep it in check, and reluctant to share power; the Duma, on the other hand, wanted continuing reform, including electoral reform, and, most prominently, land reform. Sergei Muromtsev, Professor of Law at Moscow University, was elected Chairman. Lev Urusov held a famous speech. Scared by this liberalism, emperor dissolved the parliament, reportedly saying "Curse the Duma. It is all Witte's doing". The same day, Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, ą¤čæčéčĆ ąÉčĆą║ą░ą┤čīąĄą▓ąĖčć ąĪč鹊ą╗čŗą┐ąĖąĮ, p=p╩▓╔Ątr ╔Ér╦łkad╩▓j╔¬v╩▓╔¬t╔Ģ st╔É╦łl╔©p╩▓╔¬n; ŌĆō ) was a Russian statesman who served as the third Prime Minister of Russia, prime minister and the Ministry ...

was named as the new prime minister who promoted a coalition cabinet

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an e ...

, as did Vasily Maklakov

Vasily Alekseyevich Maklakov (; ŌĆō July 15, 1957) was a Russian student activist, a trial lawyer and liberal parliamentary deputy, an orator, and one of the leaders of the Constitutional Democratic Party, notable for his advocacy of a constitu ...

, Alexander Izvolsky

Count Alexander Petrovich Izvolsky or Iswolsky (, in Moscow ŌĆō 16 August 1919 in Paris) was a Russian diplomat remembered as a major architect of Russia's alliance with Great Britain during the years leading to the outbreak of the First Worl ...

, Dmitri Trepov and the emperor.

In frustration, Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, ą¤ą░╠üą▓ąĄą╗ ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░╠üąĄą▓ąĖčć ą£ąĖą╗čÄą║ąŠ╠üą▓, p=m╩▓╔¬l╩▓╩Ŗ╦łkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the C ...

, who regarded the Russian Constitution of 1906

The Russian Constitution of 1906 refers to a major revision of the 1832 Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, which transformed the formerly absolutist state into one in which the emperor agreed for the first time to share his autocratic power ...

as a mock-constitution, and approximately 200 deputies mostly from the liberal Kadet

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchyŌĆöamong other policiesŌĆ ...

s party decamped to Vyborg

Vyborg (; , ; , ; , ) is a town and the administrative center of Vyborgsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Karelian Isthmus near the head of Vyborg Bay, northwest of St. Petersburg, east of the Finnish capital H ...

, then part of Russian Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland was the predecessor state of modern Finland. It existed from 1809 to 1917 as an Autonomous region, autonomous state within the Russian Empire.

Originating in the 16th century as a titular grand duchy held by the Monarc ...

, to discuss the way forward. From there, they issued the Vyborg Appeal

The "Vyborg Manifesto" (, , ; also called the "Vyborg Appeal") was a proclamation signed by several Russian politicians, primarily Constitutional Democratic Party, Kadets and Trudoviks) of the dissolved First Duma on .

In the wake of the 1905 Rev ...

, which called for civil disobedience and a revolution. Largely ignored, it ended in their arrest and the closure of Kadet Party offices. This, among other things, helped pave the way for an alternative makeup for the second Duma.

Second Duma

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was

The Second Duma (from 20 February 1907 to 3 June 1907) lasted 103 days. One of the new members was Vladimir Purishkevich

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich (, ; ŌĆō 1 February 1920) was a Russian politician and right-wing extremist known for his monarchist, ultra-nationalist, antisemitic and anticommunist views. He helped lead the paramilitary Black Hundreds duri ...

, strongly opposed to the October Manifesto

The October Manifesto (), officially "The Manifesto on the Improvement of the State Order" (), is a document that served as a precursor to the Russian Empire's first Constitution, which was adopted the following year in 1906. The Manifesto was is ...

. The Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s and Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

s (that is, both factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

) and the Socialist Revolutionaries all abandoned their policies of boycotting elections to the Duma, and consequently won a number of seats. The election was an overall success for Russian left-wing parties: the Trudoviks

The Trudoviks () were a democratic socialist political party of Russia in the early 20th century.

History

The Trudoviks were a breakaway of the Socialist Revolutionary Party faction as they defied the party's stance by standing in the First ...

won 104 seats, the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

65 (47 Mensheviks and 18 Bolsheviks), the Socialist Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Soviet Russia. The party members were known as Esers ().

The SRs were agr ...

37 and the Popular Socialists

The Popular Socialist Party () emerged in Russia in the early twentieth century.

History

The roots of the Popular Socialist Party (NSP) lay in the 'Legal Populist' movement of the 1890s, and its founders looked upon N.K. Mikhailovsky and Alexa ...

16.

The Kadets (by this point the most moderate and centrist party), found themselves outnumbered two-to-one by their more radical counterparts. Even so, Stolypin and the Duma could not build a working relationship, being divided on the issues of land confiscation (which the socialists and, to a lesser extent, the Kadets, supported but the tsar and Stolypin vehemently opposed) and Stolypin's brutal attitude towards law and order.

On 1 June 1907, prime minister Stolypin accused Social Democrats of preparing an armed uprising and demanded that the Duma exclude 55 Social Democrats from Duma sessions and strip 16 of their parliamentary immunity

Parliamentary immunity, also known as legislative immunity, is a system in which politicians or other political leaders are granted full immunity from legal prosecution, both civil prosecution and criminal prosecution, in the course of the exe ...

. When this ultimatum was rejected by Duma, it was dissolved on 3 June by an ukase

In Imperial Russia, a ukase () or ukaz ( ) was a proclamation of the tsar, government, or a religious leadership (e.g., Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' or the Most Holy Synod) that had the force of law. " Edict" and " decree" are adequate trans ...

(imperial decree) in what became known as the Coup of June 1907

The Coup of June 1907, sometimes known as the Stolypin Coup, was a ''coup d'├®tat'' by the cabinet of Pyotr Stolypin and Tsar Nicholas II against the State Duma of the Russian Empire. During the coup, the government dissolved the Second State ...

.

The tsar was unwilling to be rid of the State Duma, despite these problems. Instead, using emergency powers, Stolypin and the tsar changed the electoral law and gave greater electoral value to the votes of landowners and owners of city properties, and less value to the votes of the peasantry, whom he accused of being "misled", and, in the process, breaking his own Fundamental Laws.

Third Duma

This ensured the third Duma (7 November 1907 ŌĆō 3 June 1912) would be dominated by gentry, landowners and businessmen. The number of deputies from non-Russian regions was greatly reduced. The system facilitated better, if hardly ideal, cooperation between the Government and the Duma; consequently, the Duma lasted a full five-year term, and succeeded in 200 pieces of legislation and voting on some 2500 bills. Due to its more noble, andGreat Russia

Great Russia, sometimes Great Rus' ( , ; , ; , ), is a name formerly applied to the territories of "Russia proper", the land that formed the core of the Grand Duchy of Moscow and later the Tsardom of Russia. This was the land to which the e ...

n composition, the third Duma, like the first, was also given a nickname, "The Duma of the Lords and Lackeys" or "The Master's Duma". The Octobrist party were the largest, with around one-third of all the deputies. This Duma, less radical and more conservative, left clear that the new electoral system would always generate a landowners-controlled Duma in which the tsar would have vast amounts of influence over, which in turn would be under complete submission to the Tsar, unlike the first two Dumas.

In terms of legislation, the Duma supported an improvement in Russia's military capabilities, Stolypin's plans for land reform, and basic social welfare measures. The power of Nicholas' hated land captains was consistently reduced. It also supported more regressive laws, however, such as on the question of Finnish autonomy and Russification

Russification (), Russianisation or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians adopt Russian culture and Russian language either voluntarily or as a result of a deliberate state policy.

Russification was at times ...

, with a fear of the empire breaking up being prevalent. Since the dissolution of the Second Duma a very large proportion of the empire was either under martial law, or one of the milder forms of the state of siege. It was forbidden, for instance, at various times and in various places, to refer to the dissolution of the Second Duma, to the funeral of the Speaker of the First Duma, Muromtsev, and the funeral of Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

, to the fanatical ight-wingmonk Iliodor

Sergei Michailovich Trufanov ( Russian: ąĪąĄčĆą│ąĄ╠üą╣ ą£ąĖčģą░╠üą╣ą╗ąŠą▓ąĖčć ąóčĆčāčäą░╠üąĮąŠą▓; formerly Hieromonk Iliodor or Hieromonk Heliodorus, ; October 19, 1880 ŌĆō 28 January 1952) was a lapsed hieromonk, a charismatic preacher, an enfant ...

, or to the notorious ''agent provocateur'', Yevno Azef

Yevno Fishelevich (Yevgeny Filippovich) Azef (; 1869ŌĆō1918) was a Russian socialist revolutionary who also operated as a double agent and agent provocateur. He worked as both an organiser of assassinations for the Socialist Revolutionary Party ...

. Stolypin was assassinated in September 1911 and replaced by his finance minister Vladimir Kokovtsov

Count Vladimir Nikolayevich Kokovtsov (; ŌĆō 29 January 1943) was a Russian politician who served as the fourth prime minister of Russia from 1911 to 1914, during the reign of Emperor Nicholas II.

Early life

He was born in Borovichi, Borov ...

. It enabled Count Kokovtsov to balance the budget regularly and even to spend on productive purposes.

Fourth Duma

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 ŌĆō 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 ŌĆō 6 October 1917, elected in September/October, was also of limited political influence. The first session was held from 15 November 1912 to 25 June 1913, and the second session from 15 October 1913 to 14 June 1914. On 1 July 1914 the tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body, but an extraordinary session was held on 26 July 1914 during the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the Great power, major powers of Europe in mid-1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I. It began on 28 June 1914 when the Serbs ...

. The third session gathered from 27 to 29 January 1915, the fourth from 19 July 1915 to 3 September, the fifth from 9 February to 20 June 1916, and the sixth from 1 November to 16 December 1916. No one exactly knew when they would resume their deliberations. It seems the last session was never opened (on 14 February), but kept closed on 27 February 1917.

There was one promising new member in Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky ( ŌĆō 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early November 1917 ( N.S.).

After th ...

, a Trudovik

The Trudoviks () were a democratic socialist political party of Russia in the early 20th century.

History

The Trudoviks were a breakaway of the Socialist Revolutionary Party faction as they defied the party's stance by standing in the First ...

, but also Roman Malinovsky

Roman Vatslavovich Malinovsky (; 18 March 1876 ŌĆō 5 November 1918) was a prominent Bolshevik politician before the Russian revolution, while at the same time working as the best-paid agent for the Okhrana, the Tsarist secret police. They codena ...

, a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

who was a double agent for the secret police. In March 1913 the Octobrists

The Union of 17 October (, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: ą×ą║čéčÅą▒čĆąĖčüčéčŗ, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in late Imperial Russia. It represent ...

, led by Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (; 14 October 1862 ŌĆō 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government.

Early years

Alexander Guchkov was born in Moscow. Unlike most ...

, President of the Duma, commissioned an investigation on Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin ( ŌĆō ) was a Russian Mysticism, mystic and faith healer. He is best known for having befriended the imperial family of Nicholas II of Russia, Nicholas II, the last Emperor of all the Russias, Emperor of Russia, th ...

to research the allegations being a Khlyst

The Khlysts or Khlysty ( rus, ąźą╗čŗčüčéčŗ, p=xl╔©╦łst╔©, "whips") were an underground Spiritual Christian sect which emerged in Russia in the 17th century.

The sect is traditionally said to have been founded in 1645 by Danilo Filippovich, a ...

. The leading party of the Octobrists divided itself into three different sections.

The Duma "met on 8 August for three hours to pass emergency war credits, ndit was not asked to remain in session because it would only be in the way." The Duma volunteered its own dissolution until 14 February 1915. A serious conflict arose in January as the government kept information on the battlefield (in April at Gorlice

Gorlice () is a town and an urban municipality ("gmina") in south-eastern Poland with around 29,500 inhabitants (2008). It is situated south east of Krak├│w and south of Tarn├│w between Jas┼éo and Nowy S─ģcz in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship (sinc ...

) secret to the Duma. In May Guchkov initiated the War Industries Committees in order to unite industrialists who were supplying the army with ammunition and military equipment, to mobilize industry for war needs and prolonged military action, to put political pressure on the tsarist government. On 17 July 1915 the Duma reconvened for six weeks. Its former members became increasingly displeased with Tsarist control of military and governmental affairs and demanded its own reinstatement. When the tsar refused its call for the replacement of his cabinet on 21 August with a "Ministry of National Confidence", roughly half of the deputies formed a "Progressive Bloc", which in 1917 became a focal point of political resistance. On 3 September 1915 the Duma prorogued.

On the eve of the war the government and the Duma were hovering round one another like indecisive wrestlers, neither side able to make a definite move. The war made the political parties more cooperative and practically formed into one party. When the tsar announced he would leave for the front at Mogilev

Mogilev (; , ), also transliterated as Mahilyow (, ), is a city in eastern Belarus. It is located on the Dnieper, Dnieper River, about from the BelarusŌĆōRussia border, border with Russia's Smolensk Oblast and from Bryansk Oblast. As of 2024, ...

, the Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. I ...

was formed, fearing Rasputin's influence over Tsarina Alexandra

Alexandra () is a female given name of Greek origin. It is the first attested form of its variants, including Alexander (, ). Etymology, Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; genitive, GEN , ; ...

would increase.

The Duma gathered on 9 February 1916 after the 76-year-old Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (; 8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 and again from 1914 to 1916, during World War I. He was the last person to have the civil rank ...

had been replaced by Boris St├╝rmer

Baron Boris Vladimirovich Shturmer (; ŌĆō ) was a Russian lawyer, a Master of Ceremonies at the Russian Court, and a district governor. He became a member of the Russian Assembly and served as prime minister in 1916. A confidant of the Empres ...

as prime minister and on the condition not to mention Rasputin. The deputies were disappointed when St├╝rmer held his speech. Because of the war, he said, it was not the time for constitutional reforms. For the first time in his life, the tsar made a visit to the Tauride Palace

Tauride Palace () is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride commissioned his favourite architect, Ivan Starov, to design his city resi ...

, which made it practically impossible to hiss at the new prime minister.

On 1 November 1916 (Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, they refer to the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries betwe ...

) the Duma reconvened and the government under Boris St├╝rmer was attacked by Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, ą¤ą░╠üą▓ąĄą╗ ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░╠üąĄą▓ąĖčć ą£ąĖą╗čÄą║ąŠ╠üą▓, p=m╩▓╔¬l╩▓╩Ŗ╦łkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the C ...

in the State Duma, not assembled since February. In his speech he spoke of "Dark Forces", and highlighted numerous governmental failures with the famous question "Is this stupidity or treason?" Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky ( ŌĆō 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early November 1917 ( N.S.).

After th ...

called the ministers "hired assassins" and "cowards" and said they were "guided by the contemptible Grishka Rasputin!" St├╝rmer and Alexander Protopopov

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov (; ŌĆō 27 October 1918) was a Russian publicist and politician who served as the interior minister from September 1916 to February 1917.

Protopopov became a leading liberal politician in Russia after the Russian ...

asked in vain for the dissolution of the Duma. St├╝rmer's resignation looked like a concession to the Duma. Ivan Grigorovich

Ivan Konstantinovich Grigorovich () (26 January 1853 ŌĆō 3 March 1930) served as Imperial Russia's last Naval Minister from 1911 until the onset of the 1917 revolution.

Early career

Grigorovich was from a Russian noble family and opted for a ...

and Dmitry Shuvayev

Dmitry Savelyevich Shuvayev (; ŌĆō 19 December 1937) was a Russian military leader, Infantry General (1912) and Ministry of War of the Russian Empire, Minister of War (1916).

Life

Dmitry Shuvayev graduated from Alexander Military School in 187 ...

declared in the Duma that they had confidence in the Russian people, the navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

, and the army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

; the war could be won.

For the Octobrists and the Kadets, who were the liberals in the parliament, Rasputin, and his support of autocracy and absolute monarchy, was one of their main obstacles. The politicians tried to bring the government under control of the Duma. "To the Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , ą×čģčĆą░ąĮą░, p=╔É╦łxran╔Ö, a=Ru-ąŠčģčĆą░ąĮą░.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

it was obvious by the end of 1916 that the liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

Duma project was superfluous, and that the only two options left were repression or a social revolution."

On 19 November Vladimir Purishkevich

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich (, ; ŌĆō 1 February 1920) was a Russian politician and right-wing extremist known for his monarchist, ultra-nationalist, antisemitic and anticommunist views. He helped lead the paramilitary Black Hundreds duri ...

, one of the founders of the Black Hundreds

The Black Hundreds were reactionary, monarchist, and ultra-nationalist groups in Russia in the early 20th century. They were staunch supporters of the House of Romanov, and opposed any retreat from the autocracy of the reigning monarch. Their na ...

, gave a speech in the Duma. He declared the monarchy had become discredited because of what he called the "ministerial leapfrog".

On 2 December, Alexander Trepov

Alexander Fyodorovich Trepov (; ; 30 September 1862 ŌĆō 10 November 1928) was the Prime Minister of the Russian Empire from 23 November 1916 until 9 January 1917. He was conservative, a monarchist, a member of the Russian Assembly, and an advo ...

ascended the tribune in the Duma to read the government programme. The deputies shouted "down with the Ministers! Down with Protopopov!" The prime minister was not allowed to speak and had to leave the rostrum three times. Trepov threatened to shut the troublesome Duma completely in its attempt to control the tsar. The tsar, his cabinet, Alexandra, and Rasputin discussed when to open the Duma, on 12 or 19 January, 1 or 14 February, or never. Rasputin suggested to keep the Duma closed until February; Alexandra and Protopopov supported him. On Friday, 16 December Milyukov stated in the Duma: "maybe e will be

E, or e, is the fifth letter and the second vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''e'' (pronounced ); plur ...

dismissed to 9 January, maybe until February", but in the evening the Duma was closed until 12 January, by a decree prepared on the day before. A military guard had been on duty at the building.

The February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

began on 22 February when the tsar had left for the front, and strikes broke out in the Putilov workshops. On 23 February (International Women's Day

International Women's Day (IWD) is celebrated on 8 March, commemorating women's fight for equality and liberation along with the women's rights movement. International Women's Day gives focus to issues such as gender equality, reproductive righ ...

), women in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

joined the strike, demanding woman suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffrage was in effect during ...

, an end to Russian food shortages, and the end of World War I. Although all gathering on the streets were absolutely forbidden, on 25 February, some 250,000 people were on strike. The tsar ordered Sergey Semyonovich Khabalov

Sergey Semyonovich Khabalov (; ŌĆö 1924) was an Imperial Russian Army general of Ossetian origin and the commander of the Petrograd military district in 1917.

Biography

Khabalov was born in the Russian Empire, and was of Ossetian origin. ...

, an inexperienced and extremely indecisive commander of the Petrograd military district

The Petersburg Military District (ą¤ąĖč鹥čĆą▒čāčĆą│čüą║ąĖą╣ ą▓ąŠąĄ╠üąĮąĮčŗą╣ ąŠ╠üą║čĆčāą│) was a Military District of the Russian Empire originally created in August 1864 following Order B-228 of Dmitry Milyutin, the Minister of War of the Russian ...

(and Nikolay Iudovich Ivanov

Nikolai Iudovich Ivanov (, tr. ; 1851 ŌĆō 27 January 1919) was a Russian artillery general in the Imperial Russian Army. In July 1914, Ivanov was given command of four armies in the Southwestern Front against the Austro-Hungarian army, winn ...

) to suppress the rioting by force. Mutinous soldiers of the fourth company of the Pavlovsky Life Guards Regiment refused to fall in on parade when commanded, shot two officers, and joined the protesters on the streets. Nikolai Pokrovsky

Nikolai Nikolaevich Pokrovsky () (27 January 1865 ŌĆō 12 December 1930) was a nationalist Russian politician and the last foreign minister of the Russian Empire.

Life

Pokrovsky was born in St Petersburg. He attended the law schools of the Imperi ...

believed that "no one neither the Duma, nor the government cannot do anything one without the other one." The liberal Vasily Maklakov

Vasily Alekseyevich Maklakov (; ŌĆō July 15, 1957) was a Russian student activist, a trial lawyer and liberal parliamentary deputy, an orator, and one of the leaders of the Constitutional Democratic Party, notable for his advocacy of a constitu ...

and Bloc spokesman, expressed his opinion that the resignation of all members of the Council of Ministers was needed, "to make it clear that they want to go in a new way." On Monday soldiers of the Volhynian Life Guards Regiment

The Volinsky Lifeguard Regiment (), more correctly translated as the Volhynian Life-Guards Regiment, was a Imperial Guard (Russia), Russian Imperial Guard infantry regiment. Created out of a single battalion of Finnish Guard Regiment in 1817, th ...

brought the Litovsky, Preobrazhensky, and Moskovsky Regiments out on the street to join the rebellion.

On the 27th the Duma delegates received an order from his Majesty that he had decided to prorogue the Duma until April, leaving it with no legal authority to act. The Duma refused to obey, and gathered in a private meeting. According to Buchanan: "It was an act of madness to prorogue the Duma at a moment like the present." "The delegates decided to form a Provisional Committee of the State Duma

The Provisional Committee of the State Duma () was a special government body established on March 12, 1917 (27 February O.S.) by the Fourth State Duma deputies at the outbreak of the February Revolution in the same year. It was formed under ...

. The Provisional Committee ordered the arrest of all the ex-ministers and senior officials."Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes (; born 20 November 1959) is a British and German historian and writer. He was a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, where he was made Emeritus Professor on his retirement in 2022.

Figes is known f ...

(2006). '' A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891ŌĆō1924'', pp. 328ŌĆō329. The Tauride Palace was occupied by the crowd and soldiers. "On the evening the Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

held its last meeting in the Marinsky Palace

Mariinsky Palace (), also known as Marie Palace, was the last neoclassical Imperial residence to be constructed in Saint Petersburg. It was built between 1839 and 1844, designed by the court architect Andrei Stackenschneider. It houses the c ...

and formally submitted its resignation to the tsar when they were cut off from the telephone. Guchkov, along with Vasily Shulgin

Vasily Vitalyevich Shulgin (; 13 January 1878 ŌĆō 15 February 1976), also known as Basil Shulgin, was a Russian conservative politician, monarchist and member of the White movement.

Young years

Shulgin was born in Kiev. His father was a Profes ...

, came to the army headquarters near Pskov

Pskov ( rus, ą¤čüą║ąŠą▓, a=Ru-ą¤čüą║ąŠą▓.oga, p=ps╦łkof; see also Names of Pskov in different languages, names in other languages) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov O ...

to persuade the tsar to abdicate. The committee sent commissars to take over ministries and other government institutions, dismissing Tsar-appointed ministers and formed the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

under Georgi Lvov.

On 2 March 1917 the Provisional government decided that the Duma would not be reconvened. Following the Kornilov affair

The Kornilov affair, or the Kornilov putsch, was an attempted military coup d'├®tat by the commander-in-chief of the Russian Army, General Lavr Kornilov, from 10 to 13 September 1917 ( O.S., 28ŌĆō31 August), against the Russian Provisional Gov ...

and the proclamation of the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federative Republic in the 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territory of the former Russian Empire after its proclamation by the Rus ...

, the State Duma was dissolved on 6 October 1917 by the Provisional Government; a Provisional Council of the Russian Republic

Provisional Council of the Russian Republic (, (also known as Pre-parliament) was a legislative assembly of the Russian Republic. It convened at the Marinsky Palace on October 20, 1917, but was dissolved by the Bolsheviks on November, 7/8, 1917. ...

was convened on 20th October 1917 as a provisional parliament, in preparation to the election of the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly () was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the February Revolution of 1917. It met for 13 hours, from 4 p.m. to 5 a.m., , whereupon it was dissolved by the Bolshevik-led All-Russian Central Ex ...

.

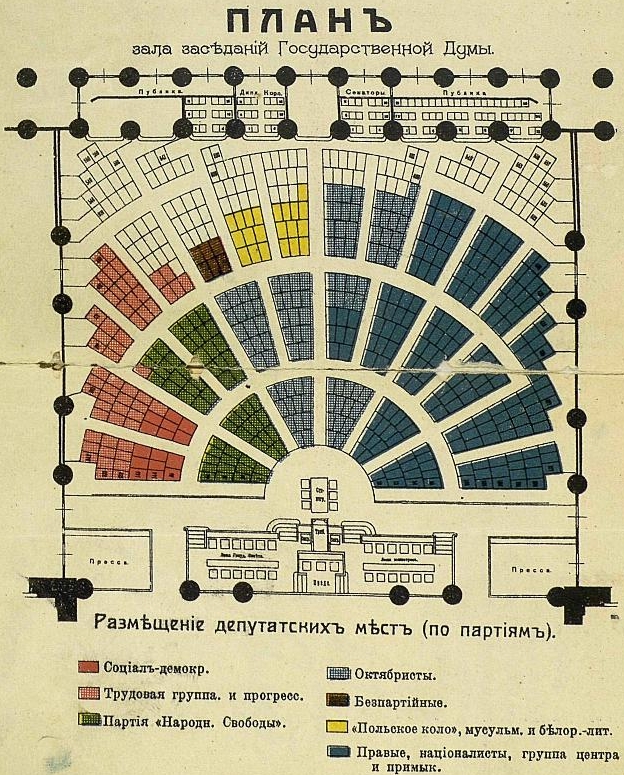

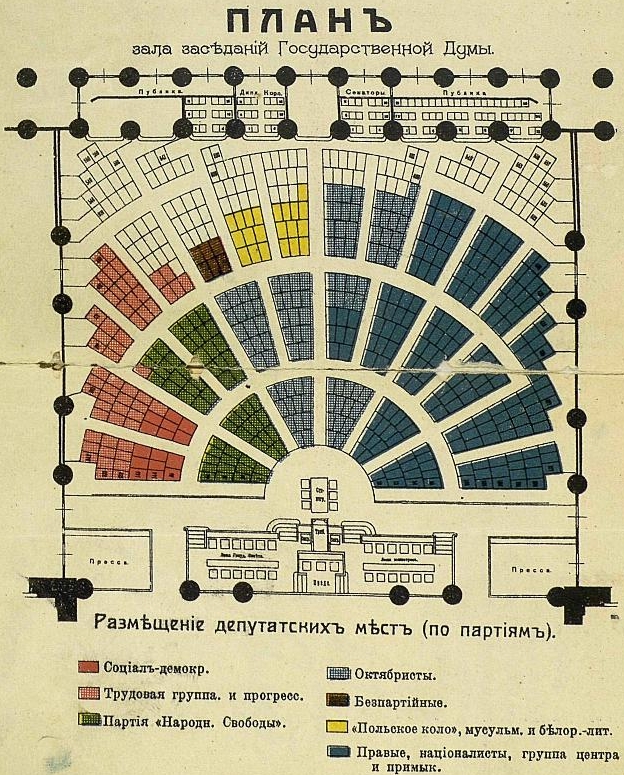

Seats held in Imperial Dumas

Chairmen of the State Duma

* Sergey Muromtsev (1906) * Fyodor Golovin (1907) * Nikolay Khomyakov (1907ŌĆō1910) *Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (; 14 October 1862 ŌĆō 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government.

Early years

Alexander Guchkov was born in Moscow. Unlike most ...

(1910ŌĆō1911)

*Mikhail Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (; ; 21 February 1859 ŌĆō 24 January 1924) was a Russian statesman of Ukrainian origin. Known for his colorful language and conservative politics, he was the State Councillor and chamberlain of the Imperial famil ...

(1911ŌĆō1917)

Deputy Chairmen of the State Duma

*The First Duma **PrincePavel Dolgorukov

Prince Pavel Dmitrievich Dolgorukov (, tr. ; 21 Nay 1866 – June 9, 1927) was a Russian landowner and aristocrat who was executed by the Bolsheviks in 1927.

Biography

Prince Pavel Dolgorukov was born in 1866. He was a member of the Dolgo ...

(Cadet Party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchyŌĆöamong other policiesŌĆ ...

) 1906

**Nikolay Gredeskul

Nikolay Andreyevich Gredeskul (Ukrainian: ąōčĆąĄą┤ąĄčüą║čāą╗ ą£ąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░ ąÉąĮą┤čĆč¢ą╣ąŠą▓ąĖčć; Russian: ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░ą╣ ąÉąĮą┤čĆąĄąĄą▓ąĖčć ąōčĆąĄą┤ąĄčüą║čāą╗; 20 April 1865 ŌĆō 8 September 1941) was a liberal politician from the Russian Empire.

...

(Cadet Party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchyŌĆöamong other policiesŌĆ ...

) 1906

*The Second Duma

**N. N. Podznansky (Left) 1907

**M. E. Berezik ( Trudoviki) 1907

*The Third Duma

**Vol. V. M. Volkonsky (moderately right), bar. A. F. Meyendorff (Octobrist), C. J. Szydlowski (Octobrist), M. Kapustin (Octobrist), I. Sozonovich (right).

*The Fourth Duma

**Prince D. D. Urusov (Progressive Bloc)

***+ Prince V. M. Volkonsky (Centrum-Right) (1912ŌĆō1913)

**Nikolay Nikolayevich Lvov (Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. I ...

) (1913)

** Aleksandr Konovalov (Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. I ...

) (1913ŌĆō1914)

**S. T. Varun-Sekret (Octobrist Party

The Union of 17 October (, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: ą×ą║čéčÅą▒čĆąĖčüčéčŗ, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in late Imperial Russia. It represente ...

) (1913ŌĆō1916)

**Alexander Protopopov

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov (; ŌĆō 27 October 1918) was a Russian publicist and politician who served as the interior minister from September 1916 to February 1917.

Protopopov became a leading liberal politician in Russia after the Russian ...

(Left Wing Octobrist Party

The Union of 17 October (, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: ą×ą║čéčÅą▒čĆąĖčüčéčŗ, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in late Imperial Russia. It represente ...

) (1914ŌĆō1916)

**Nikolai Vissarionovich Nekrasov

Nikolai Vissarionovich Nekrasov () (, Saint Petersburg ŌĆō May 7, 1940, Moscow) was a Russian liberal politician and the last Governor-General of Finland.

Biography

Parliamentary career

Born in the family of a priest, Nekrasov graduated with a ...

(Cadet Party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchyŌĆöamong other policiesŌĆ ...

) (1916ŌĆō1917)

**Count V. A. Bobrinsky (Nationalist) (1916ŌĆō1917)

Notes

References

External links

*Speech from the Throne by Nicholas II at Opening of the State Duma, photo essay with commentary

Four Dumas of Imperial Russia

{{Authority control 1905 establishments in the Russian Empire 1917 disestablishments in Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

Government of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

Historical legislatures in Russia