Dorothy Parker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild; August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet and writer of fiction, plays and screenplays based in New York; she was known for her caustic wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles.

Parker rose to acclaim, both for her literary works published in magazines, such as ''

Parker's career took off in 1918 while she was writing theater criticism for ''Vanity Fair'', filling in for the vacationing P. G. Wodehouse. At the magazine, she met

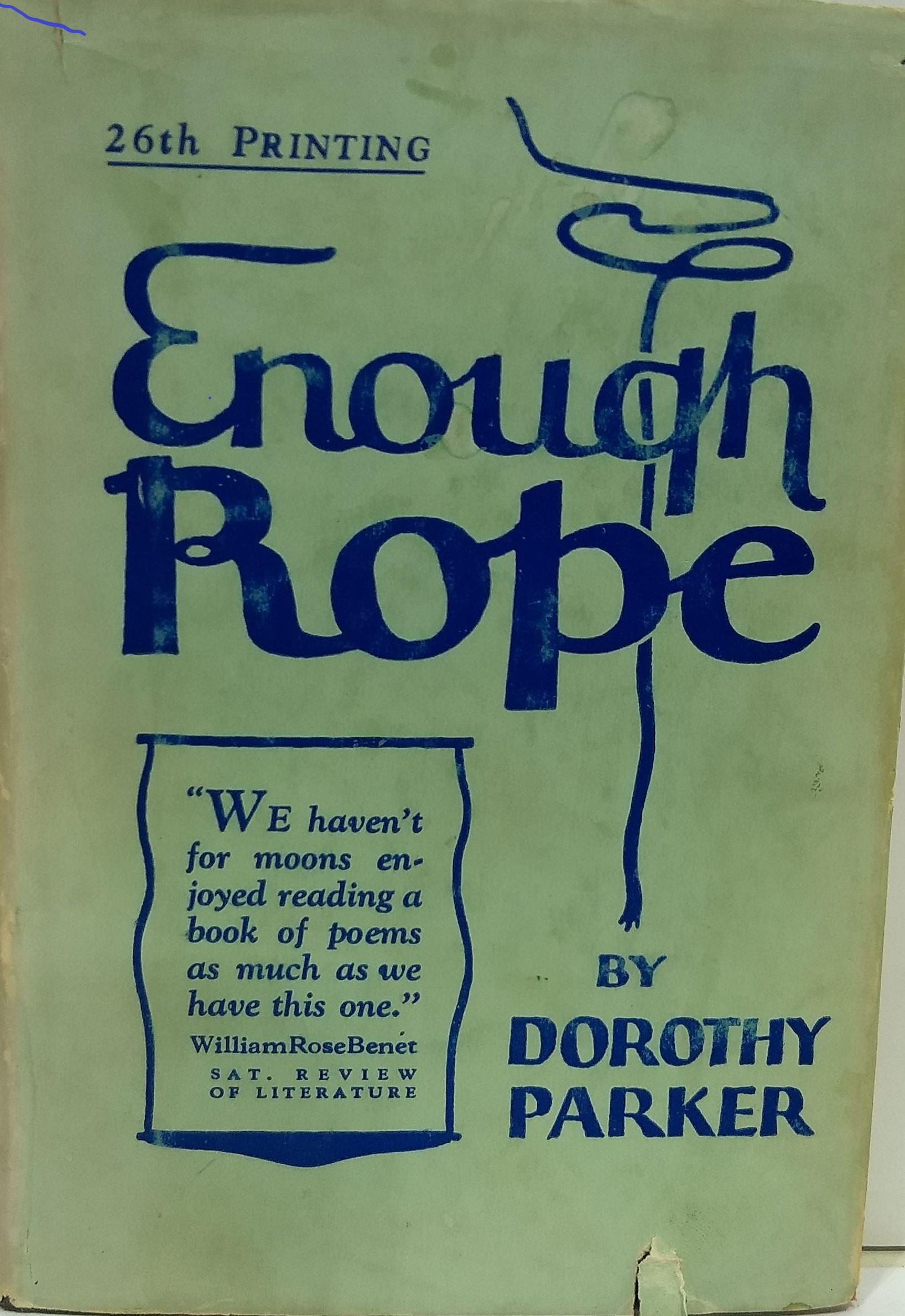

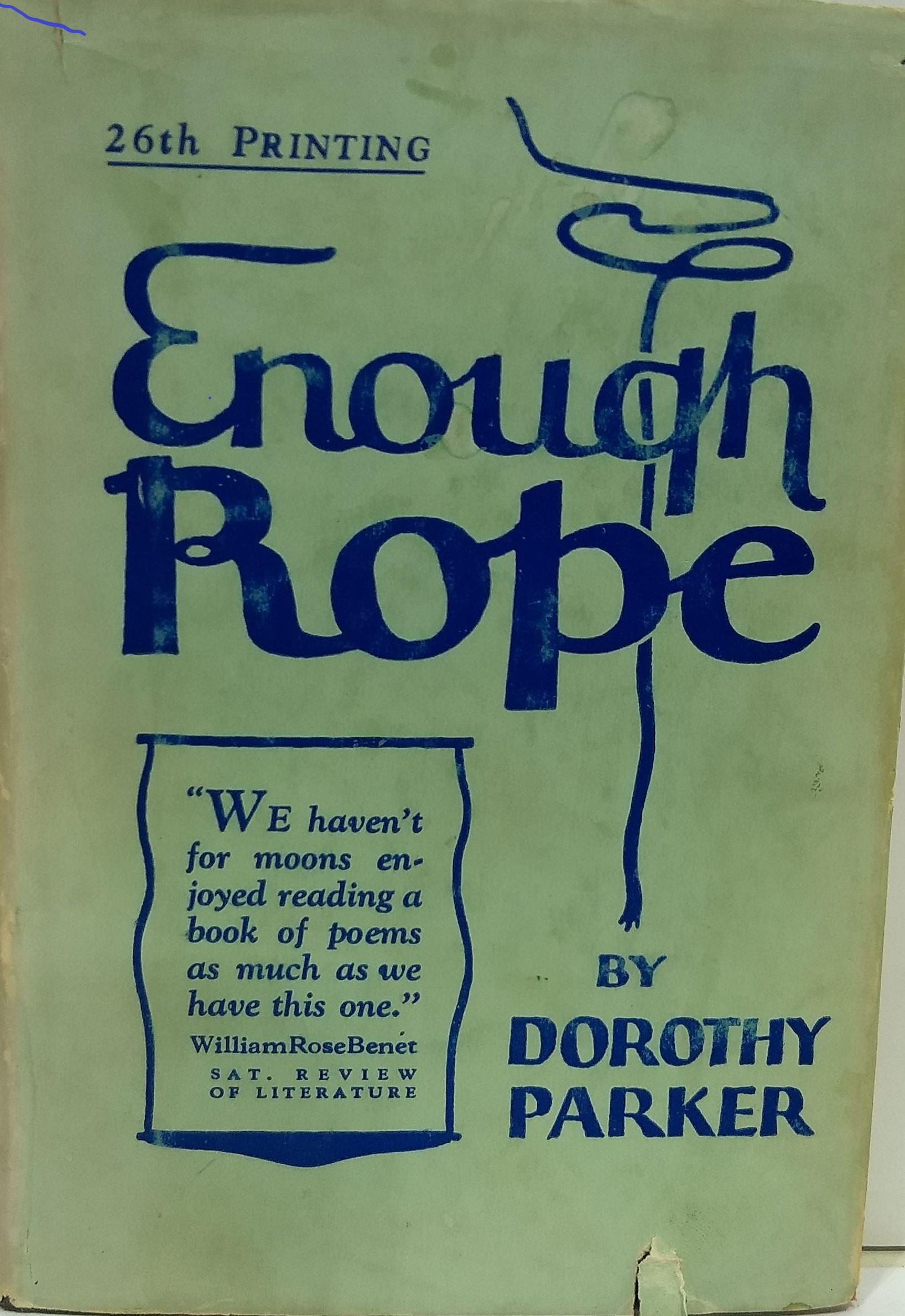

Parker's career took off in 1918 while she was writing theater criticism for ''Vanity Fair'', filling in for the vacationing P. G. Wodehouse. At the magazine, she met  Parker published her first volume of poetry, ''Enough Rope'', in 1926. It sold 47,000 copies and garnered impressive reviews. ''

Parker published her first volume of poetry, ''Enough Rope'', in 1926. It sold 47,000 copies and garnered impressive reviews. ''

In early 2020, the NAACP moved its headquarters to downtown Baltimore and how this might affect Parker's ashes became the topic of much speculation, especially after the NAACP formally announced it would later move to Washington, D.C.

The NAACP restated that Parker's ashes would ultimately be where her family wished. "It’s important to us that we do this right," said the

In early 2020, the NAACP moved its headquarters to downtown Baltimore and how this might affect Parker's ashes became the topic of much speculation, especially after the NAACP formally announced it would later move to Washington, D.C.

The NAACP restated that Parker's ashes would ultimately be where her family wished. "It’s important to us that we do this right," said the

A Telephone Call

*Short story: " Here We Are"

Dorothy Parker Society

Algonquin Round Table

Dorothy Parker

photo gallery;

Best under appreciated local landmark: Dorothy Parker Memorial Garden

, ''

coverage of Dorothy Parker

— Emdashes'' (Emily Gordon) Online works * * * * *

Selected Poems by Dorothy Parker

—

Dorothy Parker's works

— ''The Wondering Minstrels Archive''

Dorothy Parker

on ''Poeticous'' Metadata * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Dorothy 1893 births 1967 deaths 20th-century American Jews 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American poets 20th-century American screenwriters 20th-century American short story writers 20th-century American women journalists 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American women writers Actresses from Manhattan Algonquin Round Table American anti-fascists American humorous poets American people of German-Jewish descent American people of Scottish descent American satirists American socialists American women non-fiction writers American women poets American women screenwriters American women short story writers Aphorists Conversationalists Hollywood blacklist Journalists from New York City Jewish American journalists Jewish American non-fiction writers Jewish American poets Jewish American screenwriters Jewish American short story writers Jewish socialists Jewish women writers Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters The New Yorker people O. Henry Award winners People from the Upper West Side Poets from New Jersey Screenwriters from New Jersey Screenwriters from New York (state) American women satirists Writers from Long Branch, New Jersey Writers from Manhattan Yaddo alumni

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'', and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of New York City writers, critics, actors, and wits. Gathering initially as part of a practical joke, members of "The Vicious Circle", as they dubbed themselves, met for lunch each day at the Algonquin Hotel ...

. In the early 1930s, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting

Screenwriting or scriptwriting is the art and craft of writing scripts for mass media such as feature films, television productions or video games. It is often a freelance profession.

Screenwriters are responsible for researching the story, dev ...

. Her successes there, including two Academy Award

The Academy Awards, commonly known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit in film. They are presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) in the United States in recognition of excellence ...

nominations, were curtailed when her involvement in left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

resulted in her being placed on the Hollywood blacklist

The Hollywood blacklist was the mid-20th century banning of suspected Communists from working in the United States entertainment industry. The blacklisting, blacklist began at the onset of the Cold War and Red Scare#Second Red Scare (1947–1957 ...

.

Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a "wisecracker". Nevertheless, both her literary output and reputation for sharp wit have endured. Some of her works have been set to music.

Early life and education

Also known as Dot or Dottie, Parker was born Dorothy Rothschild in 1893 to Jacob Henry Rothschild and his wife Eliza Annie (née Marston) (1851–1898) at 732 Ocean Avenue in Long Branch,New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

. Parker wrote in her essay "My Home Town" that her parents returned from their summer beach cottage there to their Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

apartment shortly after Labor Day

Labor Day is a Federal holidays in the United States, federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the first Monday of September to honor and recognize the Labor history of the United States, American labor movement and the works and con ...

(September 4) so that she could be called a true New Yorker.

Parker's mother was of Scottish descent. Her father was the son of Sampson Jacob Rothschild (1818–1899) and Mary Greissman (b. 1824), both Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n-born Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. Sampson Jacob Rothschild was a merchant who immigrated to the United States around 1846, settling in Monroe County, Alabama

Monroe County is a County (United States), county located in the southwestern part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 19,772. Its county seat is Monroeville, Alabama, Monroeville. ...

. Dorothy's father was one of five known siblings: Simon (1854–1908); Samuel (b. 1857); Hannah (1860–1911), later Mrs. William Henry Theobald; and Martin, born in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

on December 12, 1865, who perished in the sinking of the ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British ocean liner that sank in the early hours of 15 April 1912 as a result of striking an iceberg on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States. Of the estimated 2,224 passengers a ...

'' in 1912.

Her mother died in Manhattan in July 1898, a month before Parker's fifth birthday. Her father remarried in 1900 to Eleanor Frances Lewis (1851–1903), a Protestant.

Author Dorothy Herrmann claimed that Parker hated her father, who allegedly physically abused her, and her stepmother, whom she refused to call "mother", "stepmother", or "Eleanor", instead referring to her as "the housekeeper". However, her biographer Marion Meade refers to this account as "largely false", stating that the atmosphere in which Parker grew up was indulgent, affectionate, supportive and generous.

Parker was raised on the Upper West Side

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper We ...

and attended a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

elementary school at the Convent of the Blessed Sacrament on West 79th Street with her sister, Helen, and classmate Mercedes de Acosta

Mercedes de Acosta (March 1, 1892 – May 9, 1968) was an American poet, playwright, and novelist. Although she failed to achieve artistic and professional distinction, de Acosta is known for her many lesbian affairs with celebrated Broadway and ...

. Parker once joked that she was asked to leave following her characterization of the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the doctrine that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception. It is one of the four Mariology, Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Debated by medieval theologians, it was not def ...

as "spontaneous combustion

Spontaneous combustion or spontaneous ignition is a type of combustion which occurs by self-heating (increase in temperature due to exothermic internal reactions), followed by thermal runaway (self heating which rapidly accelerates to high tem ...

".

Her stepmother died in 1903, when Parker was nine. Parker later attended Miss Dana's School, a finishing school

A finishing school focuses on teaching young women social graces and upper-class cultural rites as a preparation for entry into society. The name reflects the fact that it follows ordinary school and is intended to complete a young woman's ...

in Morristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a Town (New Jersey), town in and the county seat of Morris County, New Jersey, Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.

. She graduated in 1911, at the age of 18, according to Kinney, just before the school closed, although Rhonda Pettit and Marion Meade state she never graduated from high school. Following her father's death in 1913, she played piano at a dancing school to earn a living while she worked on her poetry.

She sold her first poem to '' Vanity Fair'' magazine in 1914 and some months later was hired as an editorial assistant for '' Vogue'', another Condé Nast

Condé Nast () is a global mass media company founded in 1909 by Condé Nast (businessman), Condé Montrose Nast (1873–1942) and owned by Advance Publications. Its headquarters are located at One World Trade Center in the FiDi, Financial Dis ...

magazine. She moved to ''Vanity Fair'' as a staff writer after two years at ''Vogue''.

In 1917, she met a Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

stockbroker

A stockbroker is an individual or company that buys and sells stocks and other investments for a financial market participant in return for a commission, markup, or fee. In most countries they are regulated as a broker or broker-dealer and ...

, Edwin Pond Parker II

(1893–1933) and they married before he left to serve in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

with the U.S. Army 4th Division.

Algonquin Round Table years

Parker's career took off in 1918 while she was writing theater criticism for ''Vanity Fair'', filling in for the vacationing P. G. Wodehouse. At the magazine, she met

Parker's career took off in 1918 while she was writing theater criticism for ''Vanity Fair'', filling in for the vacationing P. G. Wodehouse. At the magazine, she met Robert Benchley

Robert Charles Benchley (September 15, 1889 – November 21, 1945) was an American humorist, newspaper columnist and actor. From his beginnings at ''The Harvard Lampoon'' while attending Harvard University, through his many years writing essays ...

, who became a close friend, and Robert E. Sherwood. The trio lunched at the Algonquin Hotel almost daily. They were founding members of what became known as the Algonquin Round Table

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of New York City writers, critics, actors, and wits. Gathering initially as part of a practical joke, members of "The Vicious Circle", as they dubbed themselves, met for lunch each day at the Algonquin Hotel ...

. Among its members were newspaper columnists Franklin P. Adams and Alexander Woollcott, as well as the editor Harold Ross, the novelist Edna Ferber

Edna Ferber (August 15, 1885 – April 16, 1968) was an American novelist, short story writer and playwright. Her novels include the Pulitzer Prize-winning '' So Big'' (1924), '' Show Boat'' (1926; made into the celebrated 1927 musical), '' Cima ...

, the reporter Heywood Broun, and the comedian Harpo Marx

Arthur "Harpo" Marx (born Adolph Marx; November 23, 1888 – September 28, 1964) was an American comedian and harpist, and the second-oldest of the Marx Brothers. In contrast to the mainly verbal comedy of his brothers Groucho and Chico, Harp ...

. Through their publication of her lunchtime remarks and short verses, particularly in Adams' column "The Conning Tower", Parker began developing a national reputation as a wit.

Even though many found Parker's caustic theater reviews very entertaining, she was dismissed by ''Vanity Fair'' on January 11, 1920, after her criticisms had too often offended the playwright–producer David Belasco, the actress Billie Burke, the impresario Florenz Ziegfeld

Florenz Edward Ziegfeld Jr. (; March 21, 1867 – July 22, 1932) was an American Broadway impresario, notable for his series of theatrical revues, the ''Ziegfeld Follies'' (1907–1931), inspired by the '' Folies Bergère'' of Paris. He al ...

, and others. Benchley resigned in protest. (Sherwood is sometimes reported to have done so too, but in fact had been fired in December 1919.) Parker soon started working for '' Ainslee's Magazine'', which had a higher circulation. Her poems and short stories were published widely, "not only in upscale places like ''Vanity Fair'' (which was happier to publish her than employ her), ''The Smart Set

''The Smart Set'' was an American monthly literary magazine, founded by Colonel William d'Alton Mann and published from March 1900 to June 1930. Its headquarters was in New York City. During its Jazz Age heyday under the editorship of H. L. Men ...

'', and '' The American Mercury'', but also in the popular ''Ladies' Home Journal

''Ladies' Home Journal'' was an American magazine that ran until 2016 and was last published by the Meredith Corporation. It was first published on February 16, 1883, and eventually became one of the leading women's magazines of the 20th centur ...

'', ''Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine published six times a year. It was published weekly from 1897 until 1963, and then every other week until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely circulated and influ ...

'', and ''Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

''".

When Harold Ross founded ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'' in 1925, Parker and Benchley were part of a board of editors he established to allay the concerns of his investors. Parker's first piece for the magazine was published in its second issue. She became famous for her short, viciously humorous poems, many highlighting ludicrous aspects of her numerous and largely unsuccessful romantic affairs, and others wistfully considering the appeal of suicide.

The next 15 years were Parker's period of greatest productivity and success. In the 1920s alone she published some 300 poems and free verses in ''Vanity Fair'', ''Vogue'', "The Conning Tower" column, and ''The New Yorker'' as well as in ''Life'', ''McCall's

''McCall's'' was a monthly United States, American women's magazine, published by the McCall Corporation, that enjoyed great popularity through much of the 20th century, peaking at a readership of 8.4 million in the early 1960s. The publication ...

'' and ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

''. Her poem "Song in a Minor Key" was published during a candid interview with New York N.E.A. writer Josephine van der Grift.

Parker published her first volume of poetry, ''Enough Rope'', in 1926. It sold 47,000 copies and garnered impressive reviews. ''

Parker published her first volume of poetry, ''Enough Rope'', in 1926. It sold 47,000 copies and garnered impressive reviews. ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'' described her verse as "caked with a salty humor, rough with splinters of disillusion, and tarred with a bright black authenticity". ''Enough Rope'' included her two-line poem "News Item""Men seldom make passes / At girls who wear glasses"that would remain among her most remembered epigrams. She amused readers with poems that had a surprise or trick ending, akin to an O. Henry short story, such as:

Although some critics, notably ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' reviewer, dismissed her work as "flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women prominent after the First World War and through the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee length was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their ...

verse", the book helped Parker's reputation for sparkling wit. She released two more volumes of verse, ''Sunset Gun'' (1928) and ''Death and Taxes'' (1931), along with the short story collections ''Laments for the Living'' (1930) and ''After Such Pleasures'' (1933). ''Not So Deep as a Well'' (1936) collected much of the material previously published in ''Rope'', ''Gun'', and ''Death''; and she re-released her fiction with a few new pieces in 1939 as ''Here Lies''.

Parker collaborated with playwright Elmer Rice

Elmer Rice (born Elmer Leopold Reizenstein, September 28, 1892 – May 8, 1967) was an American playwright. He is best known for his plays '' The Adding Machine'' (1923) and his Pulitzer Prize-winning drama of New York tenement life, '' Street Sce ...

to create ''Close Harmony'', which ran on Broadway in December 1924. The play was well received in out-of-town previews and favorably reviewed in New York, but it closed after only 24 performances. As ''The Lady Next Door'', it became a successful touring production.

Some of Parker's most celebrated work was published in ''The New Yorker'' in the form of acerbic book reviews under the byline "Constant Reader". Her response to the whimsy of A. A. Milne's '' The House at Pooh Corner'' was "Tonstant Weader fwowed up." Her reviews appeared semi-regularly from 1927 to 1933, and were deemed "immensely popular". They were posthumously published in 1970 in a collection titled ''Constant Reader'', and then anthologized again in 2024.

Her best-known short story, "Big Blonde", published in '' The Bookman'', was awarded the O. Henry Award as the best short story of 1929. Her short stories, though often witty, were also spare and incisive, and more bittersweet than comic; her poetry has been described as sardonic.

Parker eventually separated from her husband Edwin Parker, divorcing in 1928. She had a number of affairs, her lovers including reporter-turned-playwright Charles MacArthur and the publisher Seward Collins

Seward Bishop Collins (April 22, 1899 – December 8, 1952) was an American New York socialite and publisher. By the end of the 1920s, he was a self-described "fascism, fascist".

Early life and education

Collins was born in Albion, Orleans Co ...

. Her relationship with MacArthur resulted in a pregnancy. Parker is alleged to have said, "how like me, to put all my eggs into one bastard". She had an abortion, and fell into a depression that culminated in her first attempt at suicide.

Toward the end of this period, Parker became more politically aware and active. What would turn into a lifelong commitment to activism began in 1927, when she grew concerned about the pending executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. Parker traveled to Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

to protest the proceedings. She and fellow Round Tabler Ruth Hale were arrested, and Parker eventually pleaded guilty to a charge of "loitering and sauntering", paying a $5 fine.

Hollywood

In February 1932, over a breakup with boyfriend John McClain, Parker attempted suicide by swallowing barbiturates. In 1932, she met Alan Campbell, an actor hoping to become a screenwriter. They married two years later inRaton, New Mexico

Raton ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Colfax County, New Mexico, Colfax County in northeastern New Mexico, United States. The city is located just south of Raton Pass. The city is also located about 6.5 miles south of the New Mexico–Col ...

. Campbell's mixed parentage was the reverse of Parker's: he had a German-Jewish mother and a Scottish father. She learned that he was bisexual

Bisexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior toward both males and females. It may also be defined as the attraction to more than one gender, to people of both the same and different gender, or the attraction t ...

and subsequently proclaimed in public that he was "queer as a billy goat". The pair moved to Hollywood and signed ten-week contracts with Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation, commonly known as Paramount Pictures or simply Paramount, is an American film production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the flagship namesake subsidiary of Paramount ...

, with Campbell (also expected to act) earning $250 per week and Parker earning $1,000 per week. They would eventually earn $2,000 and sometimes more than $5,000 per week as freelancers for various studios. She and Campbell " eceivedwriting credit for over 15 films between 1934 and 1941".

In 1933, when informed that famously taciturn former president Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

had died, Parker remarked, "How could they tell?"

In 1935, Parker contributed lyrics for the song " I Wished on the Moon", with music by Ralph Rainger

Ralph Rainger ( Reichenthal; October 7, 1901 – October 23, 1942) was an American composer of popular music principally for films.

Biography

Born Ralph Reichenthal in New York City, United States, Rainger initially embarked on a legal career, ...

. The song was introduced in '' The Big Broadcast of 1936'' by Bing Crosby

Harry Lillis "Bing" Crosby Jr. (May 3, 1903 – October 14, 1977) was an American singer, comedian, entertainer and actor. The first multimedia star, he was one of the most popular and influential musical artists of the 20th century worldwi ...

.

With Campbell and Robert Carson, she wrote the script for the 1937 film '' A Star Is Born'', for which they were nominated for an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, commonly known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit in film. They are presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) in the United States in recognition of excellence ...

for Best Writing—Screenplay. She wrote additional dialogue for '' The Little Foxes'' in 1941. Together with Frank Cavett, she received a "Writing (Motion Picture Story)" Oscar nomination for '' Smash-Up, the Story of a Woman'' (1947), starring Susan Hayward

Susan Hayward (born Edythe Marrener; June 30, 1917 – March 14, 1975) was an American actress best known for her film portrayals of women that were based on true stories.

After working as a fashion model for the Walter Clarence Thornton, Walt ...

.

After the U.S. entered the Second World War, Parker and Alexander Woollcott collaborated to produce an anthology of her work as part of a series published by Viking Press

Viking Press (formally Viking Penguin, also listed as Viking Books) is an American publishing company owned by Penguin Random House. It was founded in New York City on March 1, 1925, by Harold K. Guinzburg and George S. Oppenheimer and then acqu ...

for servicemen overseas. With an introduction by W. Somerset Maugham, ''The Portable Dorothy Parker'' (1944) compiled over two dozen of her short stories, along with selected poems from ''Enough Rope'', ''Sunset Gun'', and ''Death and Taxes''. In 1976, when a revised and enlarged edition of the book was released, the "Publishers' Note" stated that of the 75 volumes in the Viking Portable Library series, ''Dorothy Parker'' was one of three—along with ''Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

'' and '' The World Bible''—that "have remained continuously in print and selling steadily through time and change."

During the 1930s and 1940s, Parker became an increasingly vocal advocate of civil liberties and civil rights and a frequent critic of authority figures. During the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, she was among numerous American intellectuals and artists who became involved in related social movements. She reported in 1937 on the Loyalist cause in Spain for the Communist magazine '' New Masses''. At the behest of Otto Katz, a covert Soviet Comintern agent and operative of German Communist Party agent Willi Münzenberg, Parker helped to found the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League in 1936, which the FBI suspected of being a Communist Party front. The League's membership eventually grew to around 4,000. According to David Caute, its often wealthy members were "able to contribute as much to ommunistParty funds as the whole American working class", although they may not have been intending to support the Party cause.

Parker also chaired the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee's fundraising arm, "Spanish Refugee Appeal". She organized Project Rescue Ship to transport Loyalist veterans to Mexico, headed Spanish Children's Relief, and lent her name to many other left-wing causes and organizations. Her former Round Table friends saw less and less of her, and her relationship with Robert Benchley became particularly strained (although they would reconcile). Parker met S. J. Perelman at a party in 1932 and, despite a rocky start (Perelman called it "a scarifying ordeal"), they remained friends for the next 35 years. They became neighbors when the Perelmans helped Parker and Campbell buy a run-down farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania

Bucks County is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 646,538, making it the List of counties in Pennsylvania, four ...

, near New Hope, a popular summer destination among many writers and artists from New York.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, Parker applied for a passport with plans to become a foreign correspondent, but her application was denied for political reasons. The FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

had compiled a 1,000-page dossier on her, detailing her involvement in leftist activities, which doomed her post-war screenwriting career. It was the time of the Second Red Scare when Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

was raising alarms about communists in government and Hollywood. In 1950, she was identified as a Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

by the anti-Communist publication '' Red Channels''. As a result, movie studio bosses placed her on the Hollywood blacklist

The Hollywood blacklist was the mid-20th century banning of suspected Communists from working in the United States entertainment industry. The blacklisting, blacklist began at the onset of the Cold War and Red Scare#Second Red Scare (1947–1957 ...

. Her final screenplay was '' The Fan'', a 1949 adaptation of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

's '' Lady Windermere's Fan'', directed by Otto Preminger

Otto Ludwig Preminger ( ; ; 5 December 1905 – 23 April 1986) was an Austrian Americans, Austrian-American film and theatre director, film producer, and actor. He directed more than 35 feature films in a five-decade career after leaving the the ...

.

With only a small income from her book royalties, Parker and Campbell moved into an apartment "in an unfashionable West Hollywood neighborhood." She collected unemployment benefits

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work d ...

while listing herself each week as available for work. Her persistent money troubles in Hollywood contributed to her harsh assessment of the place during a 1956 interview in New York:

Her marriage to Campbell was tempestuous, with tensions exacerbated by her increasing alcohol consumption and by his long-term affair with a married woman in Europe during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Parker and Campbell divorced in 1947, remarried in 1950, and then separated again in 1952 when she moved back to New York. From 1957 to 1962, she wrote book reviews for ''Esquire

Esquire (, ; abbreviated Esq.) is usually a courtesy title. In the United Kingdom, ''esquire'' historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentleman ...

''. Her writing became increasingly erratic owing to her continued abuse of alcohol. She returned to Hollywood in 1961, reconciled once more with Campbell, and collaborated with him on a number of unproduced projects until Campbell died from a drug overdose in 1963.

Later life and death

Following Campbell's death, Parker returned to New York City and the Volney residential hotel. In her later years, she denigrated the Algonquin Round Table, although it had brought her such early notoriety: Parker occasionally participated in radio programs, including '' Information Please'' (as a guest) and ''Author, Author'' (as a regular panelist). She wrote for the '' Columbia Workshop'', and bothIlka Chase

Ilka Chase (April 8, 1905 – February 15, 1978) was an American actress, radio host, and novelist whose career spanned stage, film, and television. Born into a well-known New York family, she made her stage debut as a child and later became a ...

and Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lifeboat (194 ...

used her material for radio monologues.

Parker died on June 7, 1967, of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

at the age of 73. In her will, she bequeathed her estate to Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

, and upon King's death, to the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

. At the time of her death, she was living at the Volney residential hotel on East 74th Street.

Burial

Following her cremation, Parker's ashes were unclaimed for several years. Finally, in 1973, the crematorium sent them to her lawyer's office; by then he had retired, and the ashes remained in his colleague Paul O'Dwyer's filing cabinet for about 17 years. In 1988, O'Dwyer brought this to public attention, with the aid of celebrity columnist Liz Smith; after some discussion, the NAACP claimed Parker's remains and designed a memorial garden for them outside its Baltimore headquarters. The plaque read: In early 2020, the NAACP moved its headquarters to downtown Baltimore and how this might affect Parker's ashes became the topic of much speculation, especially after the NAACP formally announced it would later move to Washington, D.C.

The NAACP restated that Parker's ashes would ultimately be where her family wished. "It’s important to us that we do this right," said the

In early 2020, the NAACP moved its headquarters to downtown Baltimore and how this might affect Parker's ashes became the topic of much speculation, especially after the NAACP formally announced it would later move to Washington, D.C.

The NAACP restated that Parker's ashes would ultimately be where her family wished. "It’s important to us that we do this right," said the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

.

Relatives called for the ashes to be moved to the family's plot in Woodlawn Cemetery, in the Bronx, where a place had been reserved for Parker by her father. On August 18, 2020, Parker's urn was exhumed. "Two executives from the N.A.A.C.P. spoke, and a rabbi who had attended her initial burial said Kaddish

The Kaddish (, 'holy' or 'sanctification'), also transliterated as Qaddish, is a hymn praising God that is recited during Jewish prayer services. The central theme of the Kaddish is the magnification and sanctification of God's name. In the lit ...

." On August 22, 2020, Parker was re-buried privately in Woodlawn, with the possibility of a more public ceremony later. "Her legacy means a lot," added representatives from the NAACP.

Honors

On August 22, 1992, the 99th anniversary of Parker's birth, theUnited States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or simply the Postal Service, is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the federal governmen ...

issued a 29¢ U.S. commemorative postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail). Then the stamp is affixed to the f ...

in the Literary Arts series. The Algonquin Round Table, as well as the number of other literary and theatrical greats who lodged at the hotel, contributed to the Algonquin Hotel's being designated in 1987 as a New York City Historic Landmark. In 1996, the hotel was designated as a National Literary Landmark by the Friends of Libraries USA, based on the contributions of Parker and other members of the Round Table. The organization's bronze plaque is attached to the front of the hotel. Parker's birthplace at the Jersey Shore was also designated a National Literary Landmark by Friends of Libraries USA in 2005 and a bronze plaque marks the former site of her family house.

In 2014, Parker was elected to the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

In popular culture

Parker inspired a number of fictional characters in several plays of her day. These included "Lily Malone" in Philip Barry's ''Hotel Universe'' (1932), "Mary Hilliard" (played by Ruth Gordon) in George Oppenheimer's ''Here Today'' (1932), "Paula Wharton" in Gordon's 1944 play '' Over Twenty-one'' (directed by George S. Kaufman), and "Julia Glenn" in the Kaufman– Moss Hart collaboration '' Merrily We Roll Along'' (1934). Kaufman's representation of her in ''Merrily We Roll Along'' led Parker, once his Round Table compatriot, to despise him. She also was portrayed as "Daisy Lester" in Charles Brackett's 1934 novel ''Entirely Surrounded''. She is mentioned in the original introductory lyrics inCole Porter

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 – October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Many of his songs became Standard (music), standards noted for their witty, urbane lyrics, and many of his scores found success on Broadway the ...

's song " Just One of Those Things" from the 1935 Broadway musical ''Jubilee'', which have been retained in the standard interpretation of the song as part of the Great American Songbook. Additionally, she was mentioned in the title & lyrics of Prince's song "The Ballad Of Dorothy Parker" on his 1987 album ''Sign o' The Times''.

Parker is a character in the novel ''The Dorothy Parker Murder Case'' by George Baxt (1984), in a series of ''Algonquin Round Table Mysteries'' by J. J. Murphy (2011– ), and in Ellen Meister's novel ''Farewell, Dorothy Parker'' (2013). She is the main character in "Love For Miss Dottie", a short story by Larry N Mayer, which was selected by writer Mary Gaitskill

Mary Gaitskill (born November 11, 1954) is an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. Her work has appeared in ''The New Yorker'', ''Harper's Magazine'', ''Esquire (magazine), Esquire'', ''The Best American Short Stories'' (1993, 20 ...

for the collection ''Best New American Voices 2009'' (Harcourt).

She has been portrayed on film and television by Dolores Sutton in ''F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood'' (1976), Rosemary Murphy

Rosemary Murphy (January 13, 1925 – July 5, 2014) was an American actress of stage, film, and television. She was nominated for three Tony Awards for her stage work, as well as two Emmy Awards for television work, winning once, for her perfo ...

in '' Julia'' (1977), Bebe Neuwirth in '' Dash and Lilly'' (1999), and Jennifer Jason Leigh

Jennifer Jason Leigh (born Jennifer Leigh Morrow; February 5, 1962) is an American actress. She began her career on television during the 1970s before making her film breakthrough in the teen film ''Fast Times at Ridgemont High'' (1982). She re ...

in '' Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle'' (1994). Neuwirth was nominated for an Emmy Award

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the year, each with their own set of rules and award categor ...

for her performance, and Leigh received a number of awards and nominations, including a Golden Globe

The Golden Globe Awards are awards presented for excellence in both international film and television. It is an annual award ceremony held since 1944 to honor artists and professionals and their work. The ceremony is normally held every Januar ...

nomination.

Television creator Amy Sherman-Palladino

Amy Sherman-Palladino (born January 17, 1966) is an American television writer, Television director, director, and producer. She is the creator of the comedy drama series ''Gilmore Girls'' (2000–2007), ''Bunheads'' (2012–2013), and ''The Marv ...

named her production company ' Dorothy Parker Drank Here Productions' in tribute to Parker.

Tucson actress Lesley Abrams wrote and performed the one-woman show ''Dorothy Parker's Last Call'' in 2009 in Tucson, Arizona, presented by the Winding Road Theater Ensemble. She reprised the role at the Live Theatre Workshop in Tucson in 2014. The play was selected to be part of the Capital Fringe Festival in DC in 2010.

In 2018, American drag queen Miz Cracker played Parker in the celebrity-impersonation game show episode of the Season 10 of ''Rupaul's Drag Race

''RuPaul's Drag Race'' is an American reality competition television series, the first in the Drag Race (franchise), ''Drag Race'' franchise, produced by World of Wonder (company), World of Wonder for Logo TV (season 1–8), WOW Presents Plus, ...

''.

In the 2018 film '' Can You Ever Forgive Me?'' (based on the 2008 memoir of the same name), Melissa McCarthy

Melissa Ann McCarthy (born August 26, 1970) is an American actress, comedian, screenwriter, and producer. She is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Melissa McCarthy, numerous accolades, including two Primetime Emmy Award ...

plays Lee Israel, an author who for a time forged

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compression (physics), compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die (manufacturing), die. Forging is often classif ...

original letters in Dorothy Parker's name.

2007 Dorothy Parker copyright trial

In ''Silverstein v. Penguin Putnam, Inc'', the plaintiff claimed copyright in certain Parker poems that had been reproduced in Penguin's ''Dorothy Parker: Complete Poems'' after appearing in ''Not Much Fun'', a volume edited by Silverstein that had been the first collection to include these particular poems.Adaptations

In 1982,Anni-Frid Lyngstad

Anni-Frid Synni Lyngstad (born 15 November 1945), also known simply as Frida, is a Swedish singer who is best known as one of the founding members and lead singers of the pop band ABBA. Courtesy titles ''Principality of Reuss-Gera, Princess Re ...

recorded "Threnody", set to music by Per Gessle, for her third solo album ''Something's Going On

''Something's Going On'' is the third solo album by Swedish singer Anni-Frid Lyngstad (Frida), one of the founding members of the Swedish pop group ABBA and her first album recorded entirely in English. Her previous two albums had been recorded i ...

'', after she offered him a book of poems by Dorothy Parker.

In the 2010s some of her poems from the early 20th century have been set to music by the composer Marcus Paus

Marcus Nicolay Paus (; born 14 October 1979) is a Norwegian composer and one of the most performed contemporary Scandinavian composers. As a classical contemporary composer he is noted as a representative of a reorientation toward tradition, tonal ...

as the operatic song cycle '' Hate Songs for Mezzo-Soprano and Orchestra'' (2014); Paus's ''Hate Songs'' was described by musicologist Ralph P. Locke as "one of the most engaging works" in recent years; "the cycle expresses Parker's favorite theme: how awful human beings are, especially the male of the species".

With the authorization of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, lyrics taken from her book of poetry ''Not So Deep as a Well'' were used in 2014 by Canadian singer Myriam Gendron to create a folk album of the same title. Also in 2014, Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

bassist/singer/composer Katie Ernst issued her album ''Little Words'', consisting of her authorized settings of seven of Parker's poems.

In 2021 her book ''Men I'm Not Married To'' was adapted as an opera of the same name by composer Lisa DeSpain and librettist Rachel J. Peters. It premiered virtually as part of Operas in Place and Virtual Festival of New Operas commissioned by Baldwin Wallace Conservatory Voice Performance, Cleveland Opera Theater, and On Site Opera on February 18, 2021.

Bibliography

Essays and reporting

* * (a collection of 31 literary reviews originally published in ''The New Yorker'', 1927–1933) * (the complete set of her ''New Yorker'' book reviews published between October 1927 and November 1928) * (compilation of reviews, edited by Fitzpatrick; most of these reviews have never been reprinted) *Short story:A Telephone Call

*Short story: " Here We Are"

Short fiction

;Collections * 1930: ''Laments for the Living'' (includes 13 short stories) ** The Sexes ** Mr. Durant ** Just a Little One ** New York to Detroit ** The Wonderful Old Gentleman ** The Mantle of Whistler ** A Telephone Call ** You Were Perfectly Fine ** Little Curtis ** The Last Tea ** Big Blonde ** Arrangement in Black and White ** Dialogue at Three in the Morning * 1933: ''After Such Pleasures'' (includes 11 short stories) ** Horsie ** Here We Are ** Too Bad ** From the Diary of a New York Lady ** The Waltz ** Dusk Before Fireworks ** The Little Hours ** Sentiment ** A Young Woman in Green Lace ** Lady With a Lamp ** Glory in the Daytime * 1939: ''Here Lies: The Collected Stories of Dorothy Parker'' (reprints of the stories from both previous collections, plus 3 new stories) ** Clothe the Naked ** Soldiers of the Republic ** The Custard Heart * 1942: ''Collected Stories'' (stories from the first two collections) * 1944: ''The Portable Dorothy Parker'' (reprints of the stories from the previous collections, plus 8 new stories and verse from 3 poetry books) ** The Lovely Leave ** The Standard of Living ** Song of the Shirt, 1941 ** Mrs. Hofstadter on Josephine Street ** Cousin Larry ** I Live on Your Visits ** Lolita ** The Bolt Behind the Blue * 1995: ''Complete Stories'' (Penguin Books

Penguin Books Limited is a Germany, German-owned English publishing, publishing house. It was co-founded in 1935 by Allen Lane with his brothers Richard and John, as a line of the publishers the Bodley Head, only becoming a separate company the ...

) (reprints of all stories, plus 13 previously uncollected stories)

** Such a Pretty Little Picture

** A Certain Lady

** Oh! He's Charming!

** Travelogue

** A Terrible Day Tomorrow

** The Garter

** The Cradle of Civilization

** But the One on the Right

** Advice to the Little Peyton Girl

** Mrs. Carrington and Mrs. Crane

** The Road Home

** The Game

** The Banquet of Crow

Poetry collections

* 1926: ''Enough Rope'' * 1928: ''Sunset Gun'' * 1931: ''Death and Taxes'' * 1936: ''Collected Poems: Not So Deep as a Well'' * 1938: ''Two-Volume Novel'' * 1944: ''Collected Poetry'' * 1996: ''Not Much Fun: The Lost Poems of Dorothy Parker'' (UK title: ''The Uncollected Dorothy Parker'') ** 2009: ''Not Much Fun: The Lost Poems of Dorothy Parker'' (2nd ed., with additional poems)Plays

* 1929: ''Close Harmony'' (withElmer Rice

Elmer Rice (born Elmer Leopold Reizenstein, September 28, 1892 – May 8, 1967) was an American playwright. He is best known for his plays '' The Adding Machine'' (1923) and his Pulitzer Prize-winning drama of New York tenement life, '' Street Sce ...

)

* 1949: ''The Coast of Illyria'' (with Ross Evans), about the murder of Mary and Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his '' Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book '' Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764� ...

's mother by Mary

* 1953: ''Ladies of the Corridor'' (with Arnaud D'Usseau

Arnaud d'Usseau (April 18, 1916 – January 29, 1990) was a playwright and B-movie screenwriter who is perhaps best remembered today for his collaboration with Dorothy Parker on the play '' The Ladies of the Corridor''.

Career

D'Usseau was bor ...

)

Screenplays

* 1936: '' Suzy'' (with Alan Campbell, Horace Jackson and Lenore J. Coffee; based on a novel by Herman Gorman) * 1937: '' A Star is Born'' (with William A. Wellman, Robert Carson and Alan Campbell) * 1938: '' Sweethearts'' (with Alan Campbell, Laura Perelman and S.J. Perelman) * 1938: ''Trade Winds

The trade winds or easterlies are permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere ...

'' (with Alan Campbell and Frank R. Adams; story by Tay Garnett)

* 1941: '' Week-End for Three'' (with Alan Campbell; story by Budd Schulberg

Budd Schulberg (born Seymour Wilson Schulberg; March 27, 1914 – August 5, 2009) was an American screenwriter, television producer, novelist and sports writer. He was known for his novels '' What Makes Sammy Run?'' (1941) and ''The Harder They ...

)

* 1942: '' Saboteur'' (with Peter Viertel and Joan Harrison)

* 1947: '' Smash-Up, the Story of a Woman'' (with Frank Cavett, John Howard Lawson and Lionel Wiggam)

* 1949: '' The Fan'' (with Walter Reisch and Ross Evans; based on '' Lady Windermere's Fan'' by Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

)

Critical studies and reviews of Parker's work

*References

Further reading

* * * * * *External links

Dorothy Parker Society

Algonquin Round Table

Dorothy Parker

photo gallery;

Getty Images

Getty Images Holdings, Inc. (stylized as gettyimages) is a visual media company and supplier of stock images, editorial photography, video, and music for business and consumers, with a library of over 477 million assets. It targets three mark ...

*Best under appreciated local landmark: Dorothy Parker Memorial Garden

, ''

Baltimore City Paper

''Baltimore City Paper'' was a free alternative weekly newspaper published in Baltimore, Maryland, United States, founded in 1977 by Russ Smith and Alan Hirsch. The most recent owner was the Baltimore Sun Media Group, which purchased the pape ...

'', September 21, 2005.

coverage of Dorothy Parker

— Emdashes'' (Emily Gordon) Online works * * * * *

Selected Poems by Dorothy Parker

—

University of Toronto Library

The University of Toronto Libraries system is the largest academic library in Canada and is ranked third among peer institutions in North America, behind only Harvard and Yale. The system consists of 40 libraries located on University of Toronto's ...

Dorothy Parker's works

— ''The Wondering Minstrels Archive''

Dorothy Parker

on ''Poeticous'' Metadata * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Dorothy 1893 births 1967 deaths 20th-century American Jews 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American poets 20th-century American screenwriters 20th-century American short story writers 20th-century American women journalists 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American women writers Actresses from Manhattan Algonquin Round Table American anti-fascists American humorous poets American people of German-Jewish descent American people of Scottish descent American satirists American socialists American women non-fiction writers American women poets American women screenwriters American women short story writers Aphorists Conversationalists Hollywood blacklist Journalists from New York City Jewish American journalists Jewish American non-fiction writers Jewish American poets Jewish American screenwriters Jewish American short story writers Jewish socialists Jewish women writers Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters The New Yorker people O. Henry Award winners People from the Upper West Side Poets from New Jersey Screenwriters from New Jersey Screenwriters from New York (state) American women satirists Writers from Long Branch, New Jersey Writers from Manhattan Yaddo alumni