Donets Campaign on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Third Battle of Kharkov was a series of battles on the Eastern Front of

On 2 February, the Red Army launched Operation Star, threatening the cities of

On 2 February, the Red Army launched Operation Star, threatening the cities of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, undertaken by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's Army Group South

Army Group South () was the name of one of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland, Army Group South was led by Ge ...

against the Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, around the city of Kharkov

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

between 19 February and 15 March 1943. Known to the German side as the Donets Campaign, and in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as the Donbass and Kharkov operations, the German counterstrike led to the recapture of the cities of Kharkov and Belgorod

Belgorod (, ) is a city that serves as the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the Seversky Donets River, approximately north of the border with Ukraine. It has a population of

It was founded in 1596 as a defensiv ...

.

As the German 6th Army was encircled in the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

, the Red Army undertook a series of wider attacks against the rest of Army Group South. These culminated on 2 January 1943 when the Red Army launched Operation Star and Operation Gallop

Operation Gallop () was a Soviet Army operation on the Eastern Front of World War II. The operation was part of a series of counteroffensives after the encirclement of Stalingrad (now Volgograd) following the German Summer offensive in 1942 ...

, which between January and early February broke German defenses and led to the Soviet recapture of Kharkov, Belgorod, Kursk

Kursk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur (Kursk Oblast), Kur, Tuskar, and Seym (river), Seym rivers. It has a population of

Kursk ...

, as well as Voroshilovgrad

Luhansk (, ; , ), also known as Lugansk (, ; , ), is a city in the Donbas in eastern Ukraine. As of 2022, the population was estimated to be making Luhansk the Cities in Ukraine, 12th-largest city in Ukraine.

Luhansk served as the administra ...

and Izium

Izium or Izyum (, ; ) is a city on the Donets River in Kharkiv Oblast, eastern Ukraine that serves as the administrative center of Izium Raion and Izium urban hromada. It is about southeast of the city of Kharkiv, the oblast's administrative cen ...

. These victories caused participating Soviet units to over-extend themselves. Freed on 2 February by the surrender of the German 6th Army, the Red Army's Central Front turned its attention west and on 25 February expanded its offensive against both Army Group South and Army Group Center

Army Group Centre () was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created during the planning of Operation Barbarossa, Germany's invasion of the So ...

. Months of continuous operations had taken a heavy toll on the Soviet forces and some divisions were reduced to 1,000–2,000 combat-effective soldiers. On 19 February, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein

Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Manstein (born Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Lewinski; 24 November 1887 – 9 June 1973) was a Germans, German Officer (armed forces), military officer of Poles (people), Polish descent who served as a ''Generalfeld ...

launched his Kharkov counterstrike, using the fresh II SS Panzer Corps and two panzer armies.

The Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

flanked, encircled, and defeated the Red Army's armored spearheads south of Kharkov. This enabled Manstein to renew his offensive against the city of Kharkov proper on 7 March. Despite orders to encircle Kharkov from the north, the SS Panzer Corps instead decided to directly engage Kharkov on 11 March. This led to four days of house-to-house fighting before Kharkov was recaptured by the SS Division Leibstandarte

The 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler or SS Division Leibstandarte, abbreviated as LSSAH (), began as Adolf Hitler's personal bodyguard unit, responsible for guarding the Führer's person, offices, and residences. Initially th ...

on 15 March. The German forces recaptured Belgorod two days later, creating the salient which in July 1943 would lead to the Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, also called the Battle of the Kursk Salient, was a major World War II Eastern Front battle between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943, resulting in ...

. The German offensive cost the Red Army an estimated 90,000 casualties

A casualty (), as a term in military usage, is a person in military service, combatant or non-combatant, who becomes unavailable for duty due to any of several circumstances, including death, injury, illness, missing, capture or desertion.

In c ...

. The house-to-house fighting in Kharkov was also particularly bloody for the German SS Panzer Corps, which had suffered approximately 4,300 men killed and wounded by the time operations ended in mid-March.

Background

At the start of 1943, the GermanWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

faced a crisis as Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

forces encircled and reduced the German 6th Army in the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

and expanded their Winter Campaign towards the Don River

The Don () is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its basin is betwee ...

. On 2 February 1943 the 6th Army's commanding officers surrendered, and an estimated 90,000 men were taken prisoner by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. Total German losses at the Battle of Stalingrad, excluding prisoners, were between 120,000 and 150,000. Throughout 1942 German casualties totaled around 1.9 million personnel, and by the start of 1943 the Wehrmacht was around 470,000 men below full strength on the Eastern Front. At the beginning of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

, the Wehrmacht was equipped with around 3,300 tanks; by 23 January only 495 tanks, mostly of older types, remained operational along the entire length of the Soviet–German front. As the forces of the Don Front The Don Front was a front of the Soviet Red Army during the Second World War, which existed between September 1942 and February 1943, and was commanded during its entire existence by Konstantin Rokossovsky. The name refers to Don River, Russia.

F ...

were destroying the German forces in Stalingrad, the Red Army's command (''Stavka

The ''Stavka'' ( Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка, ) is a name of the high command of the armed forces used formerly in the Russian Empire and Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrat ...

'') ordered the Soviet forces to conduct a new offensive, which encompassed the entire southern wing of the Soviet–German front from Voronezh

Voronezh ( ; , ) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on the Southeastern Railway, which connects wes ...

to Rostov

Rostov-on-Don is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the East European Plain on the Don River, from the Sea of Azov, directly north of t ...

.

On 2 February, the Red Army launched Operation Star, threatening the cities of

On 2 February, the Red Army launched Operation Star, threatening the cities of Belgorod

Belgorod (, ) is a city that serves as the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the Seversky Donets River, approximately north of the border with Ukraine. It has a population of

It was founded in 1596 as a defensiv ...

, Kharkov

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

and Kursk

Kursk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur (Kursk Oblast), Kur, Tuskar, and Seym (river), Seym rivers. It has a population of

Kursk ...

. A Soviet drive, spearheaded by four tank corps organized under Lieutenant-General Markian Popov

Markian Mikhaylovich Popov (; 15 November 1902 – 22 April 1969) was a Soviet military commander, Army general (Soviet Union), Army General (26 August 1943), and Hero of the Soviet Union (1965).

Early life

Markian Popov was born in 1902 in U ...

, pierced the German front by crossing the Donets River and pressing into the German rear. On 15 February, two fresh Soviet tank corps threatened the city of Zaporizhia

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper River. It is the administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia has a population of

...

on the Dnieper River

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

, which controlled the last major road to Rostov

Rostov-on-Don is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the East European Plain on the Don River, from the Sea of Azov, directly north of t ...

and housed the headquarters of Army Group South and ''Luftflotte 4

''Luftflotte'' 4For an explanation of the meaning of Luftwaffe unit designation see Luftwaffe Organisation (Air Fleet 4) was one of the primary divisions of the German Luftwaffe in World War II. It was formed on 18 March 1939, from Luftwaffenkomm ...

'' (Air Fleet Four). Despite Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's orders to hold the city, Kharkov was abandoned by German forces and the city was recaptured by the Red Army on 16 February.

Hitler immediately flew to Manstein's headquarters at Zaporizhia. Manstein informed him that an immediate counterattack on Kharkov would be fruitless, but that he could successfully attack the overextended Soviet flank with his five Panzer corps, and recapture the city later.

On 19 February Soviet armored units broke through the German lines and approached the city. In view of the worsening situation, Hitler gave Manstein operational freedom. When Hitler departed, the Soviet forces were only some away from the airfield.

In conjunction with Operation Star the Red Army also launched Operation Gallop

Operation Gallop () was a Soviet Army operation on the Eastern Front of World War II. The operation was part of a series of counteroffensives after the encirclement of Stalingrad (now Volgograd) following the German Summer offensive in 1942 ...

south of Star, pushing the Wehrmacht away from the Donets, taking Voroshilovgrad

Luhansk (, ; , ), also known as Lugansk (, ; , ), is a city in the Donbas in eastern Ukraine. As of 2022, the population was estimated to be making Luhansk the Cities in Ukraine, 12th-largest city in Ukraine.

Luhansk served as the administra ...

and Izium

Izium or Izyum (, ; ) is a city on the Donets River in Kharkiv Oblast, eastern Ukraine that serves as the administrative center of Izium Raion and Izium urban hromada. It is about southeast of the city of Kharkiv, the oblast's administrative cen ...

, worsening the German situation further. By this time Stavka believed it could decide the war in the southwest Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

and eastern Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

, expecting total victory.

The surrender of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad freed six Soviet armies, under the command of Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Konstantinovich Rokossovsky ( 1896 – 3 August 1968) was a Soviet and Polish general who served as a top commander in the Red Army during World War II and achieved the ranks of Marshal of the Soviet Union and Marshal of Poland. He a ...

, which were refitted and reinforced by the 2nd Tank Army and the 70th Army. These forces were repositioned in the junction between German Army Groups Center and South. Known to the Soviet forces as the Kharkov and Donbass operations, the offensive sought to surround and destroy German forces in the Orel salient, cross the Desna River

The Desna ( Russian and ) is a river in Russia and Ukraine, a major left-tributary of the Dnieper. Its name in means "right hand". It has a length of , and its drainage basin covers .Army Group Center

Army Group Centre () was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created during the planning of Operation Barbarossa, Germany's invasion of the So ...

. Originally planned to begin between 12 and 15 February, deployment problems forced Stavka to push the start date back to 25 February. Meanwhile, the Soviet 60th Army pushed the German Second Army's 4th Panzer Division away from Kursk, while the Soviet 13th Army forced the Second Panzer Army to turn on its flank. This opened a breach between these two German forces, shortly to be exploited by Rokossovsky's offensive. While the Soviet 14th and 48th Armies attacked the Second Panzer Army's right flank, making minor gains, Rokossovsky launched his offensive on 25 February, breaking through German lines and threatening to surround and cut off the German Second Panzer Army and the Second Army, to the south. Unexpected German resistance began to slow the operation considerably, offering Rokossovsky only limited gains on the left flank of his attack and in the center. Elsewhere, the Soviet 2nd Tank Army had successfully penetrated of the German rear, along the left flank of the Soviet offensive, increasing the length of the army's flank by an estimated .

While the Soviet offensive continued, Field Marshal von Manstein was able to put the SS Panzer Corps – now reinforced by the 3rd SS Panzer Division

The 3rd SS Panzer Division "Totenkopf" () was an elite division of the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany during World War II, formed from the Standarten of the SS-TV. Its name, ''Totenkopf'', is German for "death's head"the skull and crossbones sy ...

– under the command of the 4th Panzer Army, while Hitler agreed to release seven understrength panzer and motorized divisions for the impending counteroffensive. The 4th Air Fleet, under the command of Field Marshal Wolfram von Richthofen

Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen (10 October 1895 – 12 July 1945) was a German World War I flying ace who rose to the rank of ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (Field Marshal) in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

In the ...

, was able to regroup and increase the number of daily sorties from an average of 350 in January to 1,000 in February, providing German forces strategic air superiority. On 20 February, the Red Army was perilously close to Zaporizhia, signaling the beginning of the German counterattack,. known to the German forces as the Donets Campaign.

Comparison of forces

Between 13 January and 3 April 1943, an estimated 210,000 Red Army soldiers took part in what was known as the Voronezh–Kharkov Offensive. In all, an estimated 6,100,000 Soviet soldiers were committed to the entire Eastern Front, with another 659,000 out of action with wounds. In comparison, the Germans could account for 2,988,000 personnel on the Eastern Front. As a result, the Red Army deployed around twice as many personnel as the Wehrmacht in early February. As a result of Soviet over-extension and the casualties they had taken during their offensive, at the beginning of Manstein's counterattack the Germans could achieve a tactical superiority in numbers, including the number of tanks present – for example, Manstein's 350 tanks outnumbered Soviet armor almost seven to one at the point of contact, and were far better supplied with fuel.German forces

At the time of the counterattack, Manstein could count on the 4th Panzer Army, composed of XLVIII Panzer Corps, the SS Panzer Corps and the First Panzer Army, with the XL and LVII Panzer Corps.. The XLVIII Panzer Corps was composed of the 6th, 11th and 17th Panzer Divisions, while the SS Panzer Corps was organized with the 1st SS, 2nd SS and 3rd SS Panzer Division.von Mellenthin (1956), p. 252 In early February, the combined strength of the SS Panzer Corps was an estimated 20,000 soldiers. The 4th Panzer Army and the First Panzer Army were situated south of the Red Army's bulge into German lines, with the First Panzer Army to the east of the 4th Panzer Army. The SS Panzer Corps was deployed along the northern edge of the bulge, on the northern front of Army Group South. The Germans were able to amass around 160,000 men against the 210,000 Red Army soldiers. The German Wehrmacht was understrength, especially after continuous operations between June 1942 and February 1943, to the point where Hitler appointed a committee made up of Field MarshalWilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal who held office as chief of the (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's armed forces, during World War II. He signed a number of criminal ...

, Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, private secretary to Adolf Hitler, and a war criminal. Bormann gained immense power by using his position as Hitler ...

and Hans Lammers

Hans Heinrich Lammers (27 May 1879 – 4 January 1962) was a German jurist and prominent Nazi Party politician. From 1933 until 1945 he served as Chief of the Reich Chancellery under Adolf Hitler. In 1937, he additionally was given the post of ' ...

, to recruit 800,000 new able-bodied men – half of whom would come from "nonessential industries". The effects of this recruitment were not seen until around May 1943, when the German armed forces were at their highest strength since the beginning of the war, with 9.5 million personnel.

By the start of 1943 Germany's armored forces had sustained heavy casualties. It was unusual for a Panzer division to field more than 100 tanks, and most averaged only 70–80 serviceable tanks at any given time. After the fighting around Kharkov, Heinz Guderian

Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (; 17 June 1888 – 14 May 1954) was a German general during World War II who later became a successful memoirist. A pioneer and advocate of the "blitzkrieg" approach, he played a central role in the development of ...

embarked on a program to bring Germany's mechanized forces up to strength. Despite his efforts, a German panzer division could only count on an estimated 10,000–11,000 personnel, out of an authorized strength of 13,000–17,000. Only by June did a panzer division begin to field between 100 and 130 tanks each. SS divisions were normally better equipped, with an estimated 150 tanks, a battalion of self-propelled assault guns and enough half-tracks to motorize most of its infantry and reconnaissance soldiers – and these had an authorized strength of an estimated 19,000 personnel. At this time, the bulk of Germany's armor was still composed of Panzer III

The ''Panzerkampfwagen III (Pz.Kpfw. III)'', commonly known as the Panzer III, was a medium tank developed in the 1930s by Nazi Germany, Germany, and was used extensively in World War II. The official German ordnance designation was List of Sd.K ...

s and Panzer IV

The IV (Pz.Kpfw. IV), commonly known as the Panzer IV, is a German medium tank developed in the late 1930s and used extensively during the Second World War. Its ordnance inventory designation was Sd.Kfz. 161.

The Panzer IV was the most numer ...

s, although the SS Division Das Reich had been outfitted with a number of Tiger I

The Tiger I () was a Nazi Germany, German heavy tank of World War II that began operational duty in 1942 in North African Campaign, Africa and in the Soviet Union, usually in independent German heavy tank battalion, heavy tank battalions. It g ...

tanks.

The 4th Panzer Army was commanded by General Hermann Hoth

Hermann Hoth (12 April 1885 – 25 January 1971) was a German army commander, war criminal, and author. He served as a high-ranking panzer commander in the Wehrmacht during World War II, playing a prominent role in the Battle of France and on th ...

, while the First Panzer Army fell under the leadership of General Eberhard von Mackensen.. The 6th, 11th and 17th Panzer Divisions were commanded by Generals Walther von Hünersdorff

__NOTOC__

Walther von Hünersdorff (28 November 1898 – 17 July 1943) was a German general during World War II who commanded the 6th Panzer Division. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and was killed dur ...

, Hermann Balck

Georg Otto Hermann Balck (7 December 1893 – 29 November 1982) was a highly decorated officer of the German Army who served in both World War I and World War II, rising to the rank of General der Panzertruppe.

Early career

Balck was born in ...

and Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, respectively. The SS Panzer Corps was commanded by General Paul Hausser

Paul Hausser, also known by his birth name Paul Falk post war (7 October 1880 – 21 December 1972), was a German general and, together with Sepp Dietrich, one of the two highest ranking commanders in the Waffen-SS. He played a key role in the ...

, who also had SS Division Totenkopf under his command.Reynolds (1997), p. 10

Red Army

Since the beginning of the Red Army's exploitation of Germany's Army Group South's defenses in late January and early February, the fronts involved included theBryansk

Bryansk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Bryansk Oblast, Russia, situated on the Desna (river), Desna River, southwest of Moscow. It has a population of 379,152 at the 2021 census.

Bryans ...

, Voronezh

Voronezh ( ; , ) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on the Southeastern Railway, which connects wes ...

and Southwestern Fronts. These were under the command of Generals M. A. Reiter, Filipp Golikov and Nikolai Vatutin

Nikolai Fyodorovich Vatutin (; 16 December 1901 – 15 April 1944) was a Soviet Union, Soviet military commander during World War II who was responsible for many Red Army operations in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian SSR as th ...

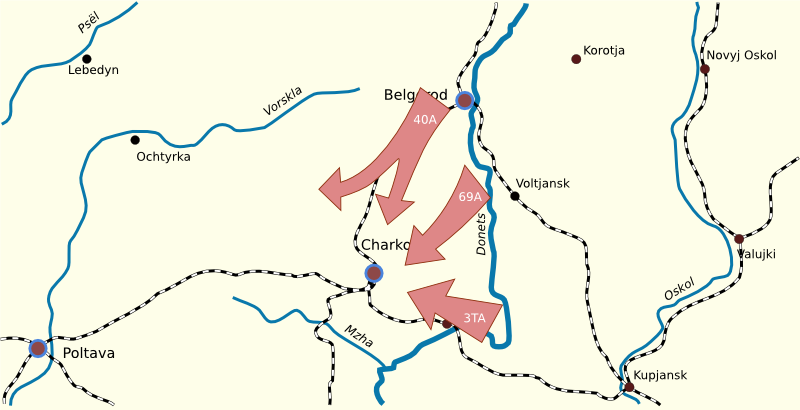

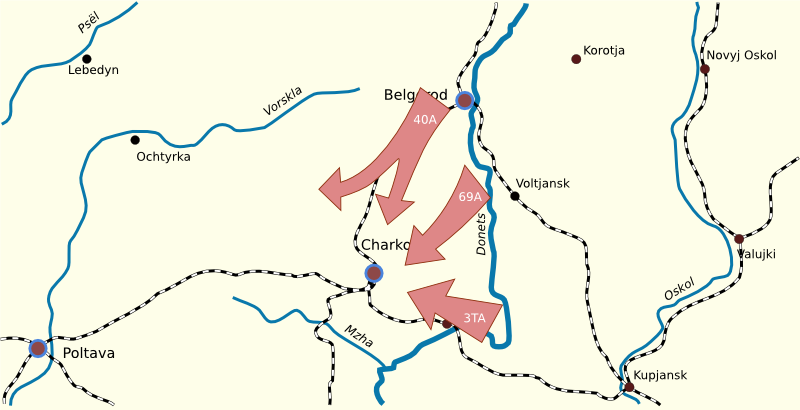

, respectively. On 25 February, Marshal Rokossovsky's Central Front also joined the battle. These were positioned in such a way that Reiter's Briansk Front was on the northern flank of Army Group South, while Voronezh was directly opposite of Kursk, and the Southwestern Front was located opposite their opponents. Central Front was deployed between the Briansk and Voronezh Fronts, to exploit the success of both of these Soviet units, which had created a gap in the defenses of the German Second Panzer Army. This involved an estimated 500,000 soldiers, while around 346,000 personnel were involved in the defense of Kharkov after the beginning of the German counterstroke.

Like their German counterparts, Soviet divisions were also seriously understrength. For example, divisions in the 40th Army averaged 3,500–4,000 men each, while the 69th Army fielded some divisions which could only count on 1,000–1,500 soldiers. Some divisions had as little as 20–50 mortars to provide fire support. This shortage in manpower and equipment led Vatutin's Southwestern Front to request over 19,000 soldiers and 300 tanks, while it was noted that the Voronezh Front had only received 1,600 replacements since the beginning of operations in 1943. By the time Manstein launched his counteroffensive, the Voronezh Front had lost so much manpower and had overextended itself to the point where it could no longer offer assistance to the Southwestern Front, south of it. The 1st Czechoslovak Independent Field Battalion, commanded by Ludvík Svoboda

Ludvík Svoboda (; 25 November 1895 – 20 September 1979) was a Czech general and politician. He fought in both World Wars, for which he was regarded as a national hero,at Sokolov.

"Kharkov 1943: The Wehrmacht’s Last Victory"

article by the military historian Robert M. Citino

Analysis of the Third Battle of Kharkov

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kharkov, 3rd Battle Of Conflicts in 1943 1943 in the Soviet Union Battles of Kharkov Battles of World War II involving Germany Battles involving the Soviet Union Battles and operations of the Soviet–German War Tank battles of World War II Tank battles involving Germany Tank battles involving the Soviet Union 1943 in Ukraine History of Belgorod February 1943 in Europe March 1943 in Europe Encirclements in World War II

Manstein's counterattack

What was known to the Germans as the Donets Campaign took place between 19 February and 15 March 1943. Originally, Manstein foresaw a three-stage offensive. The first stage encompassed the destruction of the Soviet spearheads, which had over-extended themselves through their offensive. The second stage included the recapture of Kharkov, while the third stage was designed to attack the Soviet forces at Kursk, in conjunction with Army Group Center – this final stage was ultimately called off due to the advent of the Soviet spring thaw (''Rasputitsa

''Rasputitsa'' (from ; literally "season of bad roads") is the mud season that occurs in various rural areas of Eastern Europe, when the rapid snowmelt or thawing of frozen ground combined with wet weather in spring, or heavy rains in autumn lea ...

'') and Army Group Center's reluctance to participate.

First stage: 19 February – 6 March

On 19 February, Hausser's SS Panzer Corps was ordered to strike southwards, to provide a screen for the 4th Panzer Army's attack. Simultaneously, Army Detachment Hollidt was ordered to contain the continuing Soviet efforts to break through German lines.Thompson (2000), p. 8 The 1st Panzer Army was ordered to drive north in an attempt to cut off and destroy Popov's Mobile Group, using accurate intelligence on Soviet strength which allowed the Wehrmacht to pick and choose their engagements and bring about tactical numerical superiority. The 1st and 4th Panzer Armies were also ordered to attack the overextended Soviet 6th Army and 1st Guards Army. Between 20 and 23 February, the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH) cut through the 6th Army's flank, eliminating the Soviet threat to the Dnieper River and successfully surrounding and destroying a number of Red Army units south of the Samara River. TheSS Division Das Reich

The 2nd SS Panzer Division ''Das Reich'' () or SS Division ''Das Reich'' was an armored division of the of Nazi Germany during World War II.

Initially formed from regiments of the ''SS-Verfügungstruppe'' (SS-VT), ''Das Reich'' initially served ...

advanced in a northeastern direction, while the SS Division Totenkopf was put into action on 22 February, advancing parallel to Das Reich. These two divisions successfully cut the supply lines to the Soviet spearheads. First Panzer Army was able to surround and pocket Popov's Mobile Group by 24 February, although a sizable contingent of Soviet troops managed to escape north. On 22 February, alarmed by the success of the German counterattack, the Soviet ''Stavka'' ordered the Voronezh Front to shift the 3rd Tank Army and 69th Army south, in an effort to alleviate pressure on the Southwestern Front and destroy German forces in the Krasnograd area.

The Red Army's 3rd Tank Army began to engage German units south of Kharkov, performing a holding action while Manstein's offensive continued. By 24 February, the Wehrmacht had pulled the Großdeutschland Division

Pan-Germanism ( or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanism seeks to unify all ethnic Germans, German-speaking people, and possibly also non-German Germanic peoples – into a sin ...

off the line, leaving the 167th and 320th infantry divisions, a regiment from the Totenkopf division and elements from the Leibstandarte division to defend the Western edge of the bulge created by the Soviet offensive. Between 24 and 27 February, the 3rd Tank Army and 69th Army continued to attack this portion of the German line, but without much success. With supporting Soviet units stretched thin, the attack began to falter. On 25 February, Rokossovky's Central Front launched their offensive between the German Second and 2nd Panzer Armies, with encouraging results along the German flanks, but struggling to keep the same pace in the center of the attack. As the offensive progressed, the attack on the German right flank also began to stagnate in the face of increased resistance, while the attack on the left began to over-extend itself.

In the face of German success against the Southwestern Front, including attempts by the Soviet 6th Army breaking out of the encirclement, ''Stavka'' ordered the Voronezh Front to relinquish control of the 3rd Tank Army to the Southwestern Front. To ease the transition, the 3rd Tank Army gave two rifle divisions to the 69th Army, and attacked south in a bid to destroy the SS Panzer Corps. Low on fuel and ammunition after the march south, the 3rd Tank Army's offensive was postponed until 3 March. The 3rd Tank Army was harassed and severely damaged by continuous German aerial attacks with Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87, popularly known as the "Stuka", is a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Condor Legion during the ...

''Stuka'' dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s. Launching its offensive on 3 March, the 3rd Tank Army's 15th Tank Corps

The 15th Tank Corps (, ''15-y tankoviy korpus'') was a Tank corps (Soviet Union), tank corps of the Soviet Union's Red Army. It formed in 1938 from a Mechanised corps (Soviet Union), mechanized corps and fought in the Soviet invasion of Poland, ...

struck into advancing units of the 3rd SS Panzer Division and immediately went on the defensive. Ultimately, the 3rd SS was able to pierce the 15th Tank Corps' lines and link up with other units of the same division advancing north, successfully encircling the Soviet tank corps. The 3rd Tank Army's 12th Tank Corps was also forced on the defensive immediately, after SS divisions Leibstandarte and Das Reich threatened to cut off the 3rd Tank Army's supply route. By 5 March, the attacking 3rd Tank Army had been badly mauled, with only a small number of men able to escape northwards, and was forced to erect a new defensive line.

The destruction of Popov's Mobile Group and the Soviet 6th Army during the early stages of the German counterattack created a large gap between Soviet lines. Taking advantage of uncoordinated and piecemeal Soviet attempts to plug this gap, Manstein ordered a continuation of the offensive towards Kharkov. Between 1–5 Panzer Army, including the SS Panzer Corps, covered and positioned itself only about south of Kharkov. By 6 March, the SS Division Leibstandarte made a bridgehead over the Mosh River, opening the road to Kharkov. The success of Manstein's counterattack forced Stavka to stop Rokossovsky's offensive.

Advance towards Kharkov: 7–10 March

While Rokossovsky's Central Front continued its offensive against the German Second Army, which had by now been substantially reinforced with fresh divisions, the renewed German offensive towards Kharkov took it by surprise. On 7 March, Manstein made the decision to press on towards Kharkov, despite the coming of the spring thaw. Instead of attacking east of Kharkov, Manstein decided to orient the attack towards the west of Kharkov and then encircle it from the north. The ''Großdeutschland'' Panzergrenadier Division had also returned to the front, and threw its weight into the attack, threatening to split the 69th Army and the remnants of the 3rd Tank Army. Between 8–9 March, the SS Panzer Corps completed its drive north, splitting the 69th and 40th Soviet Armies, and on 9 March it turned east to complete its encirclement. Despite attempts by the ''Stavka'' to curtail the German advance by throwing in the freshly released 19th Rifle Division and 186th Tank Brigade, the German drive continued. On 9 March, the Soviet 40th Army counterattacked against the ''Großdeutschland'' Division in a final attempt to restore communications with the 3rd Tank Army. This counterattack was caught by the expansion of the German offensive towards Kharkov on 10 March. That same day, the 4th Panzer Army issued orders to the SS Panzer Corps to take Kharkov as soon as possible, prompting Hausser to order an immediate attack on the city by the three SS Panzer divisions. ''Das Reich'' would come from the West, LSSAH would attack from north, and ''Totenkopf'' would provide a protective screen along the north and northwestern flanks. Despite attempts by General Hoth to order Hausser to stick to the original plan, the SS Panzer Corps commander decided to continue with his own plan of attack on the city, although Soviet defenses forced him to postpone the attack until the next day. Manstein issued an order to continue outflanking the city, although leaving room for a potential attack on Kharkov if there was little Soviet resistance, but Hausser decided to disregard the order and continue with his own assault.Fight for the city: 11–15 March

Early morning 11 March, the LSSAH launched a two-prong attack into northern Kharkov. The 2ndPanzergrenadier

(), abbreviated as ''PzG'' (WWII) or ''PzGren'' (modern), meaning ''Armoured fighting vehicle, "Armour"-ed fighting vehicle "Grenadier"'', is the German language, German term for the military doctrine of mechanized infantry units in armoured fo ...

Regiment, advancing from the Northwest, split up into two columns advancing towards northern Kharkov on either side of the Belgorod-Kharkov railroad. The 2nd Battalion, on the right side of the railroad, attacked the city's Severnyi Post district, meeting heavy resistance and advancing only to the Severnyi railway yard by the end of the day. On the opposite side of the railroad, the 1st Battalion struck at the district of Alexeyevka, meeting a T-34

The T-34 is a Soviet medium tank from World War II. When introduced, its 76.2 mm (3 in) tank gun was more powerful than many of its contemporaries, and its 60-degree sloped armour provided good protection against Anti-tank warfare, ...

-led Soviet counterattack which drove part of the 1st Battalion back out of the city. Only with aerial and artillery support provided by Ju 87 ''Stuka'' dive bombers and StuG assault guns were the German infantry able to battle their way into the city. A flanking attack from the rear finally allowed the German forces to achieve a foothold in that area of the city. Simultaneously, the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, with armor attached from a separate unit, attacked down the main road from Belgorod, fighting an immediate counterattack produced over the Kharkov's airport, coming on their left flank. Fighting their way past Soviet T-34s, this German contingent was able to lodge itself into Kharkov's northern suburbs. From the northeast, another contingent of German infantry, armor and self-propelled guns attempted to take control of the road exits to the cities of Rogan and Chuhuiv. This attack penetrated deeper into Kharkov, but low on fuel the armor was forced to entrench itself and turn to the defensive.

''Das Reich'' division attacked on the same day, along the west side of Kharkov. After penetrating into the city's Zalyutino district, the advance was stopped by a deep anti-tank ditch, lined with Soviet defenders, including anti-tank guns

An anti-tank gun is a form of artillery designed to destroy tanks and other armoured fighting vehicles, normally from a static defensive position. The development of specialized anti-tank munitions and anti-tank guns was prompted by the appearance ...

. A Soviet counterattack was repulsed after a bloody firefight. A detachment of the division fought its way to the southern approaches of the city, cutting off the road to Merefa. At around 15:00, Hoth ordered Hausser to immediately disengage with ''SS Das Reich'', and instead redeploy to cut off escaping Soviet troops. Instead, Hausser sent a detachment from SS ''Totenkopf'' division for this task and informed Hoth that the risk of disengaging with ''SS Das Reich'' was far too great. On the night of 11–12 March, a breakthrough element crossed the anti-tank ditch, taking the Soviet defenders by surprise, and opening a path for tanks to cross. This allowed ''Das Reich'' to advance to the city's main railway station, which would be the farthest this division would advance into the city. Hoth repeated his order at 00:15, on 12 March, and Hausser replied as he had replied on 11 March. A third attempt by Hoth was obeyed, and ''Das Reich'' disengaged, using a corridor opened by LSSAH to cross northern Kharkov and redeploy east of the city.

On 12 March, the LSSAH made progress into the city's center, breaking through the staunch Soviet defenses in the northern suburbs and began a house to house fight towards the center. By the end of the day, the division had reached a position just two blocks north of Dzerzhinsky Square. The 2nd Panzergrenadier Regiment's 2nd Battalion was able to surround the square, after taking heavy casualties from Soviet snipers and other defenders, by evening. When taken, the square was renamed "''Platz der Leibstandarte''". That night, 2nd Panzergrenadier Regiment's 3rd Battalion, under the command of Joachim Peiper

Joachim Peiper (30 January 1915 – 14 July 1976) was a German ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) colonel, convicted war criminal and car salesman. During the Second World War in Europe, Peiper served as personal adjutant to Heinrich Himmler, leader of the ...

linked up with the 2nd Battalion in Dzerzhinsky Square and attacked southwards, crossing the Kharkiv River and creating a bridgehead, opening the road to Moscow Avenue. Meanwhile, the division's left wing reached the junction of the Volchansk and Chuhuiv exit roads and went on the defensive, fighting off a number of Soviet counterattacks.

The next day, the LSSAH struck southwards towards the Kharkov River from Peiper's bridgehead, clearing Soviet resistance block by block. In a bid to trap the city's defenders in the center, the 1st Battalion of the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Regiment re-entered the city using the Volchansk exit road. At the same time, Peiper's forces were able to breakout south, suffering from bitter fighting against a tenacious Soviet defense, and link up with the division's left wing at the Volchansk and Chuhuiv road junction. Although the majority of ''Das Reich'' had, by now, disengaged from the city, a single Panzergrenadier Regiment remained to clear the southwestern corner of the city, eliminating resistance by the end of the day. This effectively put two-thirds of the city under German control.

Fighting in the city began to wind down on 14 March. The day was spent with the LSSAH clearing the remnants of Soviet resistance, pushing east along a broad front. By the end of the day, the entire city was declared to be back in German hands. Despite the declaration that the city had fallen, fighting continued over the next two days, as German units cleared the remnants of resistance in the tractor works factory complex, in the southern outskirts of the city.

Aftermath

Army Group South's Donets Campaign had cost the Red Army over 80,000 personnel casualties. Of these troops lost, an estimated 45,200 were killed or went missing, while another 41,200 were wounded. Between April and July 1943, the Red Army took its time to rebuild its forces in the area and prepare for an eventual renewal of the German offensive, known as theBattle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, also called the Battle of the Kursk Salient, was a major World War II Eastern Front battle between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943, resulting in ...

. Overall German casualties are more difficult to come by but clues are provided by examining the casualties of the SS Panzer Corps, taking into consideration that the Waffen-SS divisions were frequently deployed where the fighting was expected to be the harshest. By 17 March, it is estimated that the SS Panzer Corps had lost around 44% of its fighting strength, including around 160 officers and about 4,300 enlisted personnel.

As the SS Panzer Corps began to emerge from the city, they engaged Soviet units positioned directly southwest of the city, including the 17th NKVD Brigade, 19th Rifle Division and 25th Guards Rifle Division. Attempts by the Red Army to re-establish communication with the remnants of the 3rd Tank Army continued, although in vain. On 14–15 March, these forces were given permission to withdraw to the northern Donets River. The Soviet 40th and 69th armies had been engaged since 13 March with the ''Großdeutschland'' Panzergrenadier Division, and had been split by the German drive. After the fall of Kharkov, the Soviet defense of the Donets had collapsed, allowing Manstein's forces to drive to Belgorod on 17 March, and take it by the next day. Muddy weather and exhaustion forced Manstein's counterstroke to end soon thereafter.

The military historian Bevin Alexander wrote that the Third Battle of Kharkov was "the last great victory of German arms in the eastern front", while the military historian Robert Citino

Robert M. Citino (born June 19, 1958) is an American military historian and the Samuel Zemurray Stone Senior Historian at the National WWII Museum. He is an authority on modern German military history, with an emphasis on World War II and the ...

referred to the operation as "not a victory at all". Borrowing from a chapter title of the book ''Manstein'' by Mungo Melvin, Citino described the battle as a "brief glimpse of victory". According to Citino, the Donets Campaign was a successful counteroffensive against an overextended and overconfident enemy and did not amount to a strategic victory.

Following the German success at Kharkov, Hitler was presented with two options. The first, known as the "backhand method" was to wait for the inevitable renewal of the Soviet offensive and conduct another operation similar to that of Kharkov – allowing the Red Army to take ground, extend itself and then counterattack and surround it. The second, or the "forehand method", encompassed a major German offensive by Army Groups South and CenterBattleField: The Battle of Kursk against the protruding Kursk salient. Hitler favoured the "forehand method", which led to the Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, also called the Battle of the Kursk Salient, was a major World War II Eastern Front battle between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943, resulting in ...

.

See also

*First Battle of Kharkov

The First Battle of Kharkov was a battle that took place from 20 to 24 October 1941 for control of the city of Kharkov, located in the Ukrainian SSR, during the final stage of Operation Barbarossa. The battle was fought between the German 6t ...

(1941)

* Second Battle of Kharkov

The Second Battle of Kharkov or Operation Fredericus was an Axis powers, Axis counter-offensive in the region around Kharkov against the Red Army Izium bridgehead offensive conducted 12–28 May 1942, on the Eastern Front (World War II), Easter ...

(1942)

* Belgorod–Kharkov offensive operation

The Belgorod–Kharkov strategic offensive operation, or simply Belgorod–Kharkov offensive operation, was a Soviet strategic summer offensive that aimed to liberate Belgorod and Kharkov, and destroy Nazi German forces of the 4th Panzer Army a ...

(August 1943)

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

"Kharkov 1943: The Wehrmacht’s Last Victory"

article by the military historian Robert M. Citino

Analysis of the Third Battle of Kharkov

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kharkov, 3rd Battle Of Conflicts in 1943 1943 in the Soviet Union Battles of Kharkov Battles of World War II involving Germany Battles involving the Soviet Union Battles and operations of the Soviet–German War Tank battles of World War II Tank battles involving Germany Tank battles involving the Soviet Union 1943 in Ukraine History of Belgorod February 1943 in Europe March 1943 in Europe Encirclements in World War II