Donald Kerst on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Donald William Kerst (November 1, 1911 – August 19, 1993) was an American

After graduation, Kerst worked at

After graduation, Kerst worked at

During

During

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

who worked on advanced particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams. Small accelerators are used for fundamental ...

concepts (accelerator physics

Accelerator physics is a branch of applied physics, concerned with designing, building and operating particle accelerators. As such, it can be described as the study of motion, manipulation and observation of relativistic charged particle beams ...

) and plasma physics

Plasma () is a state of matter characterized by the presence of a significant portion of charged particles in any combination of ions or electrons. It is the most abundant form of ordinary matter in the universe, mostly in stars (including th ...

. He is most notable for his development of the betatron

A betatron is a type of cyclic particle accelerator for electrons. It consists of a torus-shaped vacuum chamber with an electron source. Circling the torus is an iron transformer core with a wire winding around it. The device functions simil ...

, a novel type of particle accelerator used to accelerate electrons

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

.

A graduate of the University of Wisconsin–Madison

The University of Wisconsin–Madison (University of Wisconsin, Wisconsin, UW, UW–Madison, or simply Madison) is a public land-grant research university in Madison, Wisconsin, United States. It was founded in 1848 when Wisconsin achieved st ...

, Kerst developed the first betatron at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC, U of I, Illinois, or University of Illinois) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area, Illinois, United ...

, where it became operational on July 15, 1940. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Kerst took a leave of absence in 1940 and 1941 to work on it with the engineering staff at General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

, and he designed a portable betatron for inspecting dud bombs. In 1943 he joined the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

, where he was responsible for designing and building the Water Boiler, a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

intended to serve as a laboratory instrument.

From 1953 to 1957 Kerst was technical director of the Midwestern Universities Research Association, where he worked on advanced particle accelerator concepts, most notably the FFAG accelerator. He was then employed at General Atomics

General Atomics (GA) is an American energy and defense corporation headquartered in San Diego, California, that specializes in research and technology development. This includes physics research in support of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion en ...

's John Jay Hopkins Laboratory from 1957 to 1962, where he worked on the problem of plasma physics. With Tihiro Ohkawa he invented toroid

In mathematics, a toroid is a surface of revolution with a hole in the middle. The axis of revolution passes through the hole and so does not intersect the surface. For example, when a rectangle is rotated around an axis parallel to one of its ...

al devices for containing the plasma with magnetic fields. Their devices were the first to contain plasma without the instabilities that had plagued previous designs, and the first to contain plasma for lifetimes exceeding the Bohm diffusion The diffusion of plasma across a magnetic field was conjectured to follow the Bohm diffusion scaling as indicated from the early plasma experiments of very lossy machines. This predicted that the rate of diffusion was linear with temperature and in ...

limit.

Early life

Donald William Kerst was born inGalena, Illinois

Galena is the largest city in Jo Daviess County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. It had a population of 3,308 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. A section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Plac ...

November 1, 1911, the son of Herman Samuel Kerst and Lillian E Wetz. He entered the University of Wisconsin

A university () is an institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars". Uni ...

, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

(BA) degree in 1934, and then his Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of Postgraduate education, graduate study and original resear ...

(PhD) in 1937, writing his thesis on "The Development of Electrostatic Generators in Air Pressure and Applications to Excitation Functions of Nuclear Reactions". This involved building and testing a 2.3 MeV

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV), also written electron-volt and electron volt, is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. When us ...

generator for experiments with the scattering of proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

s.

Betatron

After graduation, Kerst worked at

After graduation, Kerst worked at General Electric Company

The General Electric Company (GEC) was a major British industrial conglomerate involved in consumer and Arms industry, defence electronics, communications, and engineering.

It was originally founded in 1886 as G. Binswanger and Company as an e ...

for a year, working on the development of x-ray tube

An X-ray tube is a vacuum tube that converts electrical input power into X-rays. The availability of this controllable source of X-rays created the field of radiography, the imaging of partly opaque objects with penetrating radiation. In contras ...

s and machines. He found this frustrating, as x-ray research required high energies that could not be produced at the time. In 1938 he accepted an offer of an instructorship at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC, U of I, Illinois, or University of Illinois) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area, Illinois, United ...

, where the head of the physics department, F. Wheeler Loomis encouraged Kerst in his efforts to create a better particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams. Small accelerators are used for fundamental ...

. The result of these efforts was the betatron

A betatron is a type of cyclic particle accelerator for electrons. It consists of a torus-shaped vacuum chamber with an electron source. Circling the torus is an iron transformer core with a wire winding around it. The device functions simil ...

. When it became operational on July 15, 1940, Kerst became the first person to accelerate electrons using electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force, electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1 ...

, reaching energies of 2.3 MeV.

In December 1941 Kerst decided on "betatron", using the Greek letter "beta", which was the symbol for electrons, and "tron" meaning "instrument for". He went on to build more betatrons of increasing energy, a 20 MeV machine in 1941, an 80 MeV in 1948, and a 340 MeV machine, which was completed in 1950.

The betatron would influence all subsequent accelerators. Its success was due to a thorough understanding of the physics involved, and painstaking design of the magnets, vacuum pumps and power supply. In 1941, he teamed up with Robert Serber

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific st ...

to provide the first theoretical analysis of the oscillations

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

that occur in a betatron. The original 1940 machine was donated to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in 1960.

World War II

During

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Kerst took a leave of absence from the University of Illinois to work on the development of the betatron with the engineering staff at General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

in 1940 and 1941. They designed 20 MeV and 100 MeV versions of the betatron, and he supervised the construction of the former, which he brought back to the University of Illinois with him. He also designed a portable 4 MeV betatron for inspecting dud bombs.

Kerst's engineering and physics background placed him near the top of the list of scientists that Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

recruited for the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

, which was set up to design the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

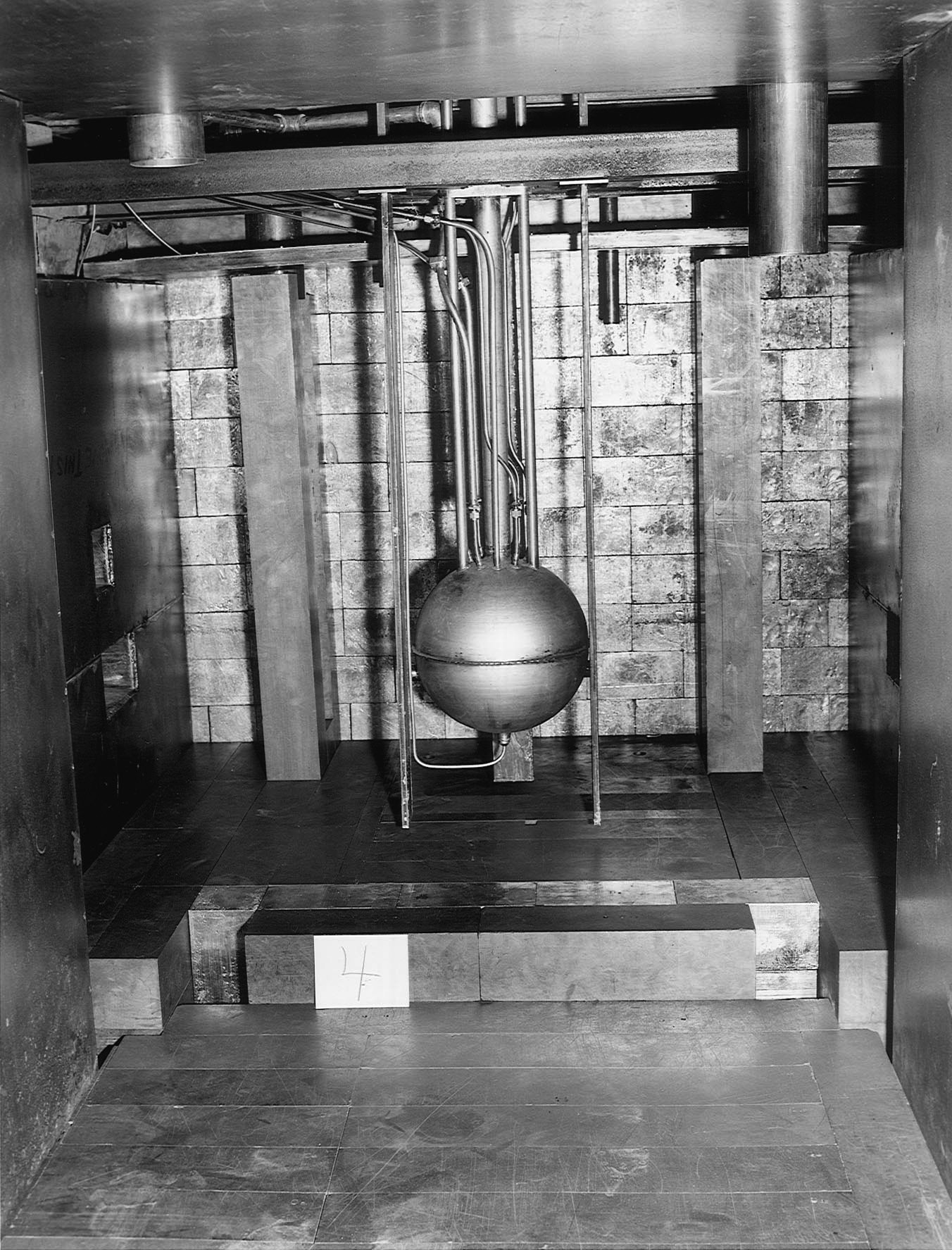

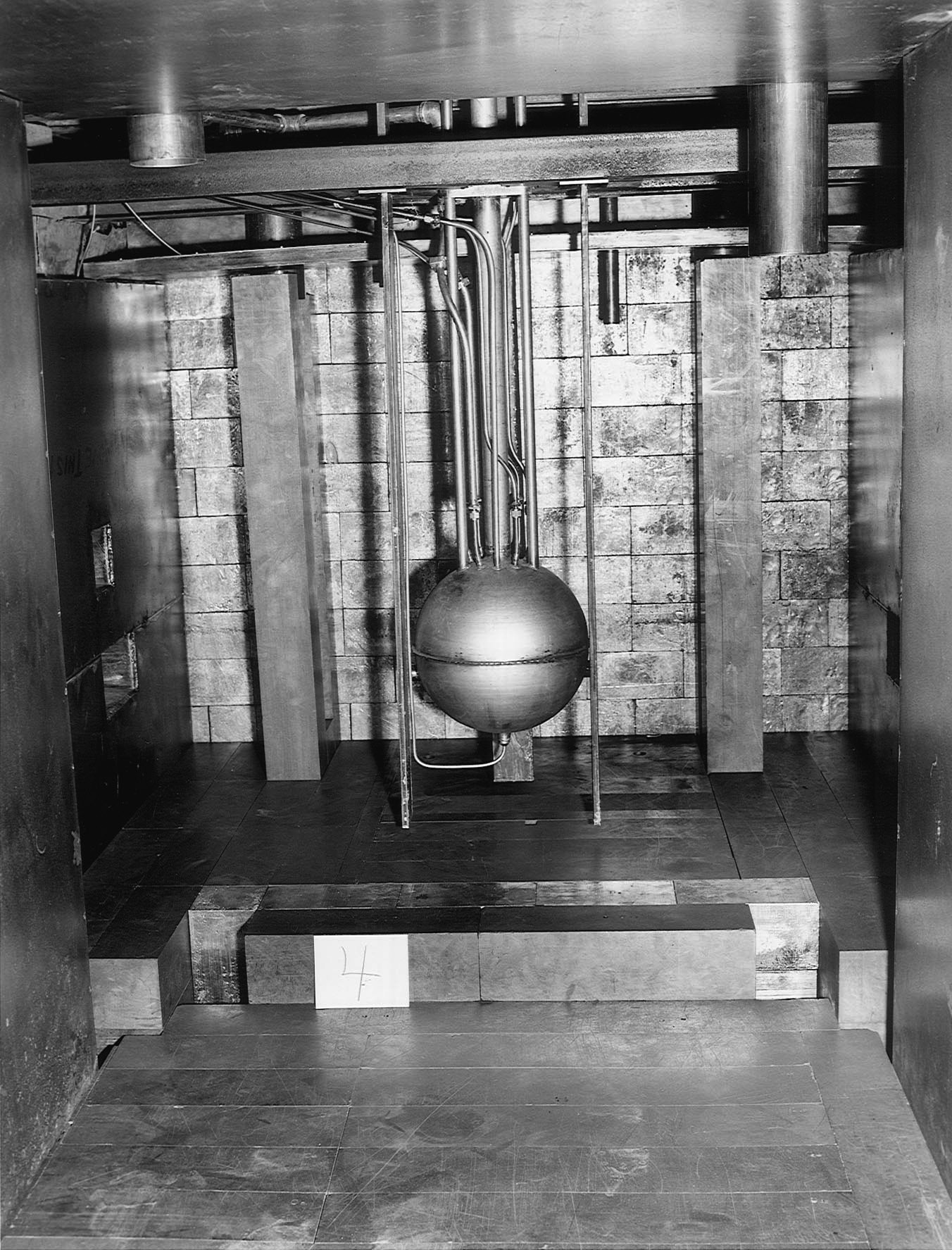

. In August 1943, Kerst was placed in charge of the Laboratory's P-7 Group, which was responsible for designing and building the Water Boiler, a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

intended to serve as a laboratory instrument to test critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

calculations and the effect of various tamper materials. Primarily drawn from Purdue University

Purdue University is a Public university#United States, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, United States, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded ...

, his group included Charles P. Baker, Gerhart Friedlander, Lindsay Helmholtz, Marshall Holloway, and Raemer Schreiber. Robert F. Christy

Robert Frederick Christy (May 14, 1916 – October 3, 2012) was a Canadian-American theoretical physicist and later astrophysicist who was one of the last surviving people to have worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He briefly ...

provided help with the theoretical calculations.

Kerst designed an aqueous homogeneous reactor

Aqueous homogeneous reactors (AHR) is a two (2) chamber reactor consisting of an interior reactor chamber and an outside cooling and moderating jacket chamber. They are a type of nuclear reactor in which soluble nuclear salts (usually uranium su ...

in which enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

in the form of soluble uranium sulfate, was dissolved in water, and surrounded by a beryllium oxide neutron reflector. It was the first reactor to employ enriched uranium as a fuel, and required most of the world's meager supply at the time. A sufficient quantity of enriched uranium arrived at Los Alamos by April 1944, and the Water Boiler commenced operation in May. By the end of June it had achieved all of its design goals.

The Los Alamos Laboratory was reorganized in August 1944 to concentrate on creating an implosion-type nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapons design are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

# Pure fission weapons are the simplest, least technically de ...

. Studying implosion on a large scale, or even a full scale, required special diagnostic methods. As early as November 1943, Kerst suggested using a betatron employing 20 MeV gamma rays

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from high energy interactions like the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei or astronomical events like solar flares. It consists o ...

instead of x-rays to study implosion. In the August 1944 reorganization, he became joint head, with Seth Neddermeyer, of the G-5 Group, part of Robert Bacher

Robert Fox Bacher (August 31, 1905November 18, 2004) was an American nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and one of the leaders of the Manhattan Project. Born in Loudonville, Ohio, Bacher obtained his undergraduate degree and doctorate from the U ...

's G (Gadget) Division specifically charged with betatron testing. Oppenheimer had the 20 MeV betatron at the University of Illinois shipped to Los Alamos, where it arrived in December. On January 15, 1945, the G-5 Group took their first betatron pictures of an implosion.

Later life

Kerst returned to the University of Illinois after the war. From 1953 to 1957 he was technical director of the Midwestern Universities Research Association, where he worked on advanced particle accelerator concepts, most notably the FFAG accelerator. He developed the spiral-sector focusing principle, which lies at the heart of many spiral ridge cyclotrons that are now in operation around the world. His team devised and analysed beam stacking, a process of radio frequency acceleration in fixed field machines that led to the development of the colliding beam accelerators. From 1957 to 1962 Kerst was employed at theGeneral Atomics

General Atomics (GA) is an American energy and defense corporation headquartered in San Diego, California, that specializes in research and technology development. This includes physics research in support of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion en ...

division of General Dynamics

General Dynamics Corporation (GD) is an American publicly traded aerospace and defense corporation headquartered in Reston, Virginia. As of 2020, it was the fifth largest defense contractor in the world by arms sales and fifth largest in the Unit ...

's John Jay Hopkins Laboratory for Pure and Applied Science in La Jolla, California

La Jolla ( , ) is a hilly, seaside neighborhood in San Diego, California, occupying of curving coastline along the Pacific Ocean. The population reported in the 2010 census was 46,781. The climate is mild, with an average daily temperature o ...

, where he worked on plasma physics

Plasma () is a state of matter characterized by the presence of a significant portion of charged particles in any combination of ions or electrons. It is the most abundant form of ordinary matter in the universe, mostly in stars (including th ...

, which it was hoped was the doorway to the control of thermonuclear energy. With Tihiro Ohkawa he invented toroid

In mathematics, a toroid is a surface of revolution with a hole in the middle. The axis of revolution passes through the hole and so does not intersect the surface. For example, when a rectangle is rotated around an axis parallel to one of its ...

al devices for containing the plasma with magnetic fields. The two completed this work at the University of Wisconsin, where Kerst was a professor from 1962 until his retirement in 1980. Their devices were the first to contain plasma without the instabilities that had plagued previous designs, and the first to contain plasma for lifetimes exceeding the Bohm diffusion The diffusion of plasma across a magnetic field was conjectured to follow the Bohm diffusion scaling as indicated from the early plasma experiments of very lossy machines. This predicted that the rate of diffusion was linear with temperature and in ...

limit. From 1972 to 1973 he was also chairman of the Plasma Physics Division of the American Physical Society.

Kerst was married to Dorothy Birkett Kerst. They had two children, a daughter, Marilyn, and a son, Stephen. After he retired, Kerst and Dorothy moved to Fort Myers, Florida

Fort Myers (or Ft. Myers) is a city in and the county seat of Lee County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 86,395; it was estimated to have grown to 95,949 in 2022, making it the List o ...

. He died on August 19, 1993, at the University Hospital and Clinics in Madison, Wisconsin

Madison is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. It is the List of municipalities in Wisconsin by population, second-most populous city in the state, with a population of 269,840 at the 2020 Uni ...

, from a brain tumor. He was survived by his wife and children. His papers are in the University of Illinois Archives.

Awards and honors

* Honorary degree, Lawrence College, 1942. * Awarded Comstock Prize in Physics,National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

, 1943.

* Awarded John Scott Award

John Scott Award, created in 1816 as the John Scott Legacy Medal and Premium, is presented to men and women whose inventions improved the "comfort, welfare, and happiness of human kind" in a significant way. "...the John Scott Medal Fund, establish ...

, City of Philadelphia, 1946.

* Awarded John Price Wetherill Medal

The John Price Wetherill Medal was an award of the Franklin Institute. It was established with a bequest given by the family of John Price Wetherill (1844–1906) on April 3, 1917. On June 10, 1925, the Board of Managers voted to create a silv ...

, Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and a center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and wikt:statesman, statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin ...

, 1950.

* Elected to the National Academy of Sciences, 1951.

* Honorary degree, University of São Paulo

The Universidade de São Paulo (, USP) is a public research university in the Brazilian state of São Paulo, and the largest public university in Brazil.

The university was founded on 25 January 1934, regrouping already existing schools in ...

, 1953.

* Honorary degree, University of Wisconsion, 1961.

* Founding member of the World Cultural Council

The World Cultural Council is an international organization whose goals are to promote cultural values, goodwill and philanthropy among individuals. The organization founded in 1982 and based in Mexico, has held a yearly award ceremony since 198 ...

, 1981.

* Awarded James Clerk Maxwell Prize in plasma physics, American Physical Society

The American Physical Society (APS) is a not-for-profit membership organization of professionals in physics and related disciplines, comprising nearly fifty divisions, sections, and other units. Its mission is the advancement and diffusion of ...

, 1984.

* Awarded Robert R. Wilson Prize for accelerator physics, 1988.

* Honorary degree, University of Illinois, 1989.

Notes

References

*External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kerst, Donald William 1911 births 1993 deaths Accelerator physicists 20th-century American physicists Founding members of the World Cultural Council Manhattan Project people Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign faculty University of Wisconsin–Madison faculty People from Galena, Illinois Fellows of the American Physical Society