Diprotodon Optatum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Diprotodon'' (

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: "two protruding front teeth") is an extinct genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

from the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

of Australia containing one species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, ''D. optatum''. The earliest finds date to 1.77 million to 780,000 years ago but most specimens are dated to after 110,000 years ago. Its remains were first unearthed in 1830 in Wellington Caves

The Wellington Caves are a group of limestone caves located south of Wellington, New South Wales, Australia.

History

The Wellington region was long inhabited by the 'Binjang mob' of the Wiradjuri, Wiradjuri people. While there is no direct ...

, New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

, and contemporaneous paleontologists guessed they belonged to rhino

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

s, elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

s, hippo

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic Mammal, mammal native to su ...

s or dugong

The dugong (; ''Dugong dugon'') is a marine mammal. It is one of four living species of the order Sirenia, which also includes three species of manatees. It is the only living representative of the once-diverse family Dugongidae; its closest ...

s. ''Diprotodon'' was formally described by English naturalist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

in 1838, and was the first named Australian fossil mammal, and led Owen to become the foremost authority of his time on other marsupials and Australian megafauna

The term Australian megafauna refers to the megafauna in Australia (continent), Australia during the Pleistocene, Pleistocene Epoch. Most of these species became extinct during the latter half of the Pleistocene, as part of the broader global L ...

, which were enigmatic to European science.

''Diprotodon'' is the largest-known marsupial to have ever lived; it greatly exceeds the size of its closest living relatives wombat

Wombats are short-legged, muscular quadrupedal marsupials of the family Vombatidae that are native to Australia. Living species are about in length with small, stubby tails and weigh between . They are adaptable and habitat tolerant, and are ...

s and koala

The koala (''Phascolarctos cinereus''), sometimes inaccurately called the koala bear, is an arboreal herbivorous marsupial native to Australia. It is the only Extant taxon, extant representative of the Family (biology), family ''Phascolar ...

s. It is a member of the extinct family Diprotodontidae

Diprotodontidae is an extinct family of large herbivorous marsupials, endemic to Australia and New Guinea during the Oligocene through Pleistocene periods from 28.4 million to 40,000 years ago.

Description

The family primarily consisted of lar ...

, which includes other large quadrupedal herbivores. It grew to at the shoulders, over from head to tail, and likely weighed several tonnes, possibly as much as . Females were much smaller than males. ''Diprotodon'' supported itself on elephant-like legs to travel long distances, and inhabited most of Australia. The digits were weak; most of the weight was probably borne on the wrists and ankles. The hindpaws angled inward at 130°. Its jaws may have produced a strong bite force

Bite force quotient (BFQ) is a numerical value commonly used to represent the bite force of an animal adjusted for its body mass, while also taking factors like the allometry effects.

The BFQ is calculated as the regression of the quotient of an ...

of at the long and ever-growing incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

teeth, and over at the last molar. Such powerful jaws would have allowed it to eat vegetation in bulk, crunching and grinding plant materials such as twigs, buds and leaves of woody plants with its bilophodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone toot ...

teeth.

It is the only marsupial and metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as wel ...

n that is known to have made seasonal migrations. Large herds, usually of females, seem to have marched through a wide range of habitats to find food and water, walking at around . ''Diprotodon'' may have formed polygynous

Polygyny () is a form of polygamy entailing the marriage of a man to several women. The term polygyny is from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); .

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any other continent. Some scholar ...

societies, possibly using its powerful incisors to fight for mates or fend off predators, such as the largest-known marsupial carnivore ''Thylacoleo carnifex

''Thylacoleo'' ("pouch lion") is an extinct genus of carnivorous marsupials that lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene (until around 40,000 years ago), often known as marsupial lions. They were the largest and last mem ...

''. Being a marsupial, the mother may have raised her joey in a pouch on her belly, probably with one of these facing backwards, as in wombats.

''Diprotodon'' went extinct about 40,000 years ago as part of the Late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions

The Late Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene saw the extinction of the majority of the world's megafauna, typically defined as animal species having body masses over , which resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity acro ...

, along with every other Australian mammal over ; the extinction was possibly caused by extreme drought conditions and predation pressure from the first Aboriginal Australian

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia 50,000 to 65,000 year ...

s, who likely co-existed with ''Diprotodon'' and other megafauna in Australia for several thousand years prior to its extinction. There is little direct evidence of interactions between Aboriginal Australians and ''Diprotodon''—or most other Australian megafauna. ''Diprotodon'' has been conjectured by some authors to have been the origin of some aboriginal mythological figures—most notably the bunyip

The bunyip is a creature from the aboriginal mythology of southeastern Australia, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes.

Name

The origin of the word ''bunyip'' has been traced to the Wemba-Wemba or Wergaia ...

—and aboriginal rock art

Indigenous Australian art includes art made by Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, including collaborations with others. It includes works in a wide range of media including painting on leaves, bark painting, wood carving, ro ...

works, but these ideas are unconfirmable.

Research history

In 1830, farmer George Ranken found a diverse fossil assemblage while exploringWellington Caves

The Wellington Caves are a group of limestone caves located south of Wellington, New South Wales, Australia.

History

The Wellington region was long inhabited by the 'Binjang mob' of the Wiradjuri, Wiradjuri people. While there is no direct ...

, New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

, Australia. This was the first major site of extinct Australian megafauna

The term Australian megafauna refers to the megafauna in Australia (continent), Australia during the Pleistocene, Pleistocene Epoch. Most of these species became extinct during the latter half of the Pleistocene, as part of the broader global L ...

. Remains of ''Diprotodon'' were excavated when Ranken later returned as part of a formal expedition that was headed by explorer Major Thomas Mitchell.

At the time these massive fossils were discovered, it was generally thought they were remains of rhinos, elephants, hippos, or dugongs. The fossils were not formally described until Mitchell took them in 1837 to his former colleague English naturalist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

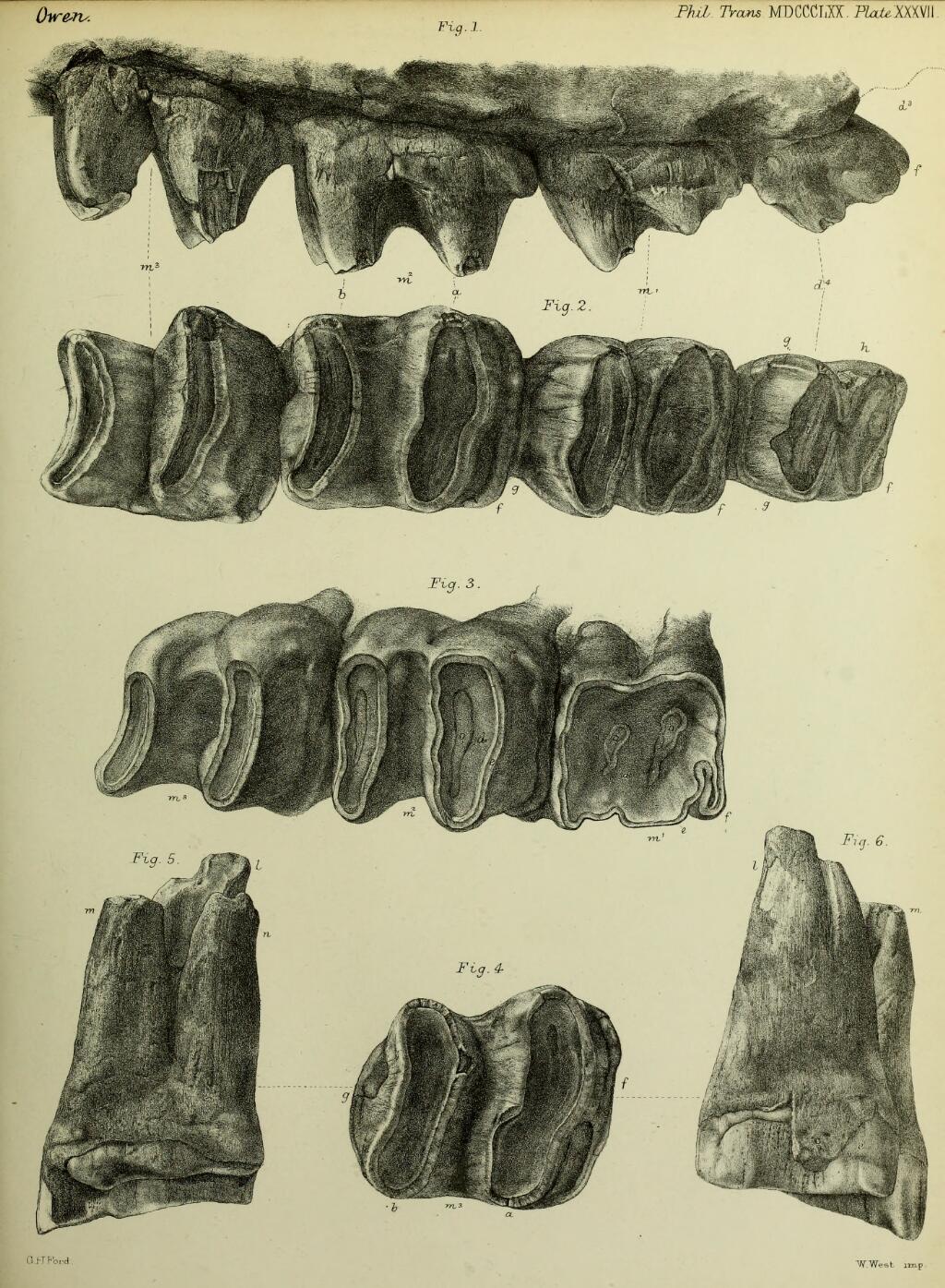

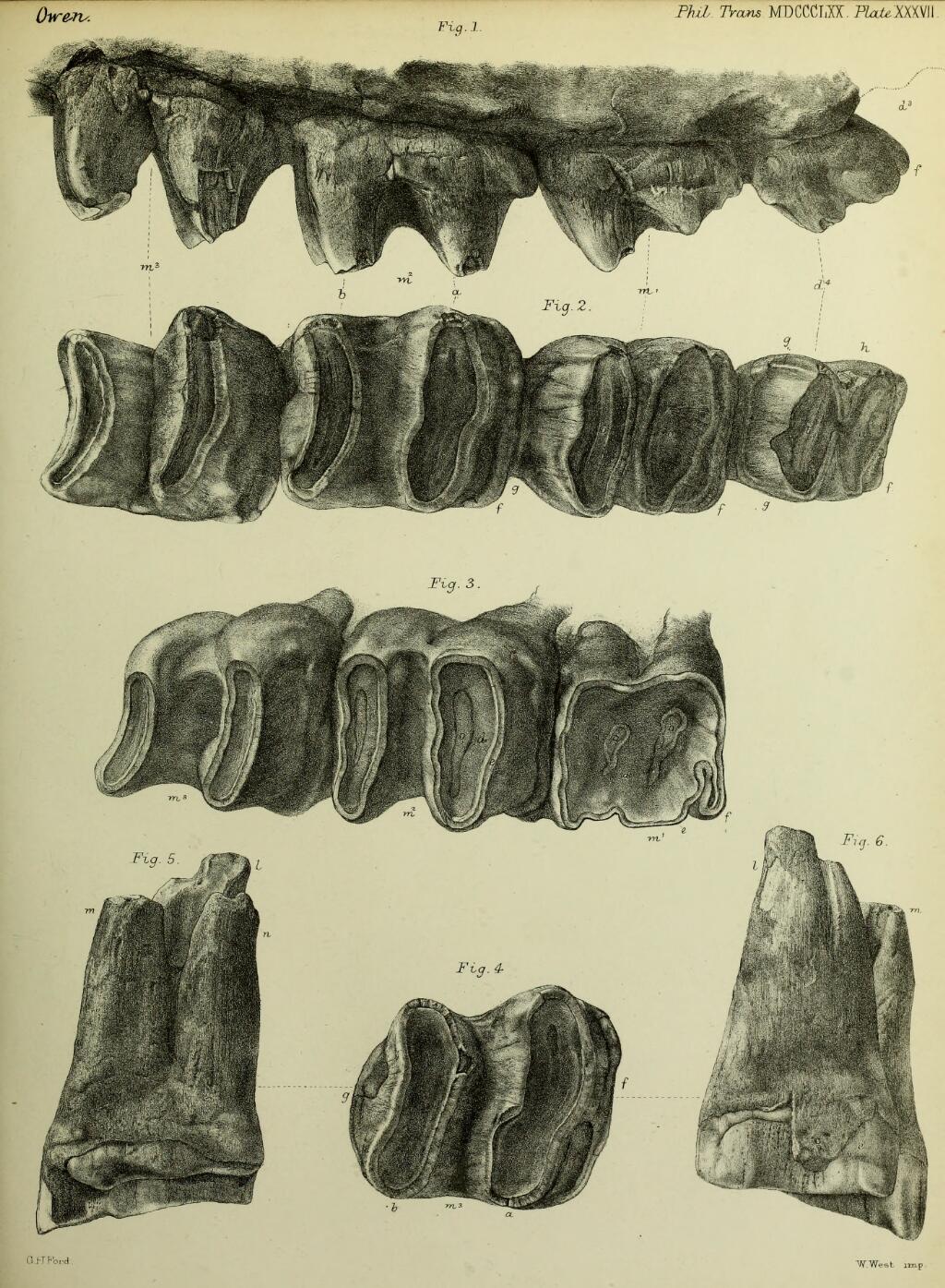

while in England publishing his journal. In 1838, while studying a piece of a right mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

with an incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

, Owen compared the tooth to those of wombats and hippos; he wrote to Mitchell designating it as a new genus ''Diprotodon''. Mitchell published the correspondence in his journal. Owen formally described ''Diprotodon'' in Volume 2 without mentioning a species; in Volume 1, however, he listed the name ''Diprotodon optatum'', making that the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

. ''Diprotodon'' means "two protruding front teeth" in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

and ''optatum'' is Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

for "desire" or "wish". It was the first-ever Australian fossil mammal to be described. In 1844, Owen replaced the name ''D. optatum'' with "''D. australis''". Owen only once used the name ''optatum'' and the acceptance of its apparent replacement "''australis''" has historically varied widely but ''optatum'' is now standard.

In 1843, Mitchell was sent more ''Diprotodon'' fossils from the recently settled Darling Downs

The Darling Downs is a farming region on the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range in southern Queensland, Australia. The Downs are to the west of South East Queensland and are one of the major regions of Queensland. The name was generally ...

and relayed them to Owen. With these, Owen surmised that ''Diprotodon'' was an elephant related to or synonymous

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

with ''Mastodon

A mastodon, from Ancient Greek μαστός (''mastós''), meaning "breast", and ὀδούς (''odoús'') "tooth", is a member of the genus ''Mammut'' (German for 'mammoth'), which was endemic to North America and lived from the late Miocene to ...

'' or ''Deinotherium

''Deinotherium'' (from Ancient Greek , ''()'', meaning "terrible", and ''()'', meaning "beast"), is an extinct genus of large, elephant-like proboscideans that lived from the middle-Miocene until the end of the Early Pleistocene. Although its ap ...

'', pointing to the incisors which he interpreted as tusks, the flattening (anteroposterior compression) of the femur similar to the condition in elephants and rhinos, and the raised ridges of the molar characteristic of elephant teeth. Later that year, he formally synonymised ''Diprotodon'' with ''Deinotherium'' as ''Dinotherium Australe'', which he recanted in 1844 after German naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt (; 23 October 1813 – ), known as Ludwig Leichhardt, was a German explorer and naturalist, most famous for his exploration of northern and central Australia.Ken Eastwood,'Cold case: Leichhardt's disappearanc ...

pointed out that the incisors clearly belong to a marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

. Owen still classified the molars from Wellington as ''Mastodon australis'' and continued to describe ''Diprotodon'' as likely elephantine. In 1847, a nearly complete skull and skeleton was recovered from the Darling Downs, the latter confirming this elephantine characterisation. The massive skeleton attracted a large audience while on public display in Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

. Leichhardt believed the animal was aquatic, and in 1844 he said it might still be alive in an undiscovered tropical area nearer the interior. But, as the European land exploration of Australia

European land exploration of Australia deals with the opening up of the interior of Australia to European settlement which occurred gradually throughout the colonial period, 1788–1900. A number of these explorers are very well known, such as ...

progressed, he became certain it was extinct. Owen later become the foremost authority of Australian palaeontology of his time, mostly working with marsupials.

Huge assemblages of mostly-complete ''Diprotodon'' fossils have been unearthed in dry lakes and riverbeds; the largest assemblage came from Lake Callabonna

Lake Callabonna is a dry salt lake with little to no vegetation located in the Far North region of South Australia. The lake is situated approximately southwest of Cameron Corner, the junction of South Australia, Queensland and New South Wal ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

. Fossils were first noticed here by an aboriginal stockman working on a sheep property to the east. The owners, the Ragless brothers, notified the South Australian Museum

The South Australian Museum is a natural history museum and research institution in Adelaide, South Australia, founded in 1856 and owned by the Government of South Australia. It occupies a complex of buildings on North Terrace in the cultur ...

, which hired Australian geologist Henry Hurst, who reported an enormous wealth of fossil material and was paid £250 in 1893 to excavate the site. Hurst found up to 360 ''Diprotodon'' individuals over a few acres; excavation was restarted in the 1970s and more were uncovered. American palaeontologist Richard H. Tedford said multiple herds of these animals had at different times become stuck in mud while crossing bodies of water while water levels were low during dry season

The dry season is a yearly period of low rainfall, especially in the tropics. The weather in the tropics is dominated by the tropical rain belt, which moves from the northern to the southern tropics and back over the course of the year. The t ...

s.

In addition to ''D. optatum'', several other species were erected in the 19th century, often from single specimens, on the basis of subtle anatomical variations. Among the variations was size difference: adult ''Diprotodon'' specimens have two distinct size ranges. In their 1975 review of Australian fossil mammals, Australian palaeontologists J. A. Mahoney and William David Lindsay Ride did not ascribe this to sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

because males and females of modern wombat and koala species—its closest living relatives—are skeletally indistinguishable, so they assumed the same would have been true for extinct relatives, including ''Diprotodon''.

These other species are:

*''D. annextans'' was erected in 1861 by Irish palaeontologist Frederick McCoy

Sir Frederick McCoy (1817 – 13 May 1899), was an Irish palaeontologist, zoologist, and museum administrator, active in Australia. He is noted for founding the Botanic Garden of the University of Melbourne in 1856.

Early life

McCoy was the s ...

based on some teeth and a partial mandible found near Colac, Victoria

Colac is a town in the Western District (Victoria), Western District of Victoria, Australia, approximately 150 kilometres south-west of Melbourne on the southern shore of Lake Colac.

History

For thousands of years clans of the Gulidjan people ...

; the name may be a typo of ''annectens'', which means linking or joining, because he characterised the species as combining traits from ''Diprotodon'' and ''Nototherium

''Nototherium'', from Ancient Greek νότος (''nótos''), meaning "south", and θηρίον (''theríon''), meaning "beast", is an extinct genus of diprotodontid marsupial from Australia and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gi ...

'';

*''D. minor'' was erected in 1862 by Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

based on a partial palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sep ...

; in 1991, Australian palaeontologist Peter Murray suggested classifying large specimens as ''D. optatum'' and smaller ones as "''D. minor''";

*''D. longiceps'' was erected in 1865 by McCoy as a replacement for "''D. annextans''";

*''D. bennettii'' was erected in 1873 by German naturalist Gerard Krefft

Johann Ludwig (Louis) Gerard Krefft (17 February 1830 – 18 February 1881), was an Australian artist, draughtsman, scientist, and natural historian who served as the curator of the Australian Museum for 13 years (1861–1874). He was one of A ...

based on a nearly complete mandible collected by naturalists George Bennet and Georgina King near Gowrie, New South Wales; and

*''D. loderi'' was erected in 1873 by Krefft based on a partial palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sep ...

collected by Andrew Loder

Andrew Loder (14 February 1826 – 19 May 1900) was an Australian politician.

He was born at Sackville Reach near Windsor, New South Wales, Windsor to farmer George Loder and Mary Howe. He worked on his father's properties, and on 14 April 1 ...

near Murrurundi

Murrurundi ( ) is a rural town located in the Upper Hunter Shire, in the Upper Hunter region of New South Wales, Australia.

Murrurundi is situated northwest by road from Newcastle and north from Sydney. At the the town had a population of 8 ...

, New South Wales.

In 2008, Australian palaeontologist Gilbert Price opted to recognise only one species ''D. optatum'' based most-notably on a lack of dental differences among these supposed species, and said it was likely ''Diprotodon'' was indeed sexually dimorphic, with the male probably being the larger form.

Classification

Phylogeny

''Diprotodon'' is a marsupial in theorder

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Diprotodontia

Diprotodontia (, from Greek language, Greek "two forward teeth") is the largest extant order (biology), order of marsupials, with about 155 species, including the kangaroos, Wallaby, wallabies, Phalangeriformes, possums, koala, wombats, and many ...

, suborder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

Vombatiformes

The Vombatiformes are one of the three suborders of the large marsupial order Diprotodontia. Seven of the nine known families within this suborder are extinct; only the families Phascolarctidae, with the koala, and Vombatidae, with three ext ...

(wombats and koalas), and infraorder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between Family_(biology), family and Class_(biology), class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classific ...

Vombatomorphia (wombats and allies). It is unclear how different groups of vombatiformes are related to each other because the most-completely known members—living or extinct—are exceptionally derived (highly specialised forms that are quite different from their last common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

).

In 1872, American mammalogist Theodore Gill

Theodore Nicholas Gill (March 21, 1837 – September 25, 1914) was an American ichthyologist, mammalogist, malacologist, and librarian.

Career

Born and educated in New York City under private tutors, Gill early showed interest in natural hist ...

erected the superfamily

SUPERFAMILY is a database and search platform of structural and functional annotation for all proteins and genomes. It classifies amino acid sequences into known structural domains, especially into SCOP superfamilies. Domains are functional, str ...

Diprotodontoidea and family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Diprotodontidae

Diprotodontidae is an extinct family of large herbivorous marsupials, endemic to Australia and New Guinea during the Oligocene through Pleistocene periods from 28.4 million to 40,000 years ago.

Description

The family primarily consisted of lar ...

to house ''Diprotodon''. New species were later added to both groups; by the 1960s, the first diprotodontoids dating to before the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Ruben A. Stirton subdivided Diprotodontoidea into one family, Diprotodontidae, with four

Diprotodontidae is the most diverse family in Vombatomorphia; it was better adapted to the spreading dry, open landscapes over the last tens of millions of years than other groups in the infraorder, living or extinct. ''Diprotodon'' has been found in every Australian state, making it the most-widespread Australian megafauna in the fossil record. The oldest vombatomorph (and vombatiform) is '' Mukupirna'', which was identified in 2020 from

Diprotodontidae is the most diverse family in Vombatomorphia; it was better adapted to the spreading dry, open landscapes over the last tens of millions of years than other groups in the infraorder, living or extinct. ''Diprotodon'' has been found in every Australian state, making it the most-widespread Australian megafauna in the fossil record. The oldest vombatomorph (and vombatiform) is '' Mukupirna'', which was identified in 2020 from

The

The

Like modern megaherbivores, most evidently the

Like modern megaherbivores, most evidently the

In 2017, by measuring the strontium isotope ratio (87Sr/86Sr) at various points along the ''Diprotodon'' incisor QMF3452 from the Darling Downs, and matching those ratios to the ratios of sites across that region, Price and colleagues determined ''Diprotodon'' made seasonal migrations, probably in search of food or watering holes. This individual appears to have been following the

In 2017, by measuring the strontium isotope ratio (87Sr/86Sr) at various points along the ''Diprotodon'' incisor QMF3452 from the Darling Downs, and matching those ratios to the ratios of sites across that region, Price and colleagues determined ''Diprotodon'' made seasonal migrations, probably in search of food or watering holes. This individual appears to have been following the

The locomotion of an extinct animal can be inferred using

The locomotion of an extinct animal can be inferred using

In 2005, American geologist Gifford Miller noticed fire abruptly becomes more common about 45,000 years ago; he ascribed this increase to aboriginal fire-stick farmers, who would have regularly started

In 2005, American geologist Gifford Miller noticed fire abruptly becomes more common about 45,000 years ago; he ascribed this increase to aboriginal fire-stick farmers, who would have regularly started

subfamilies

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zool ...

; Diprotodontinae (containing ''Diprotodon'' among others), Nototheriinae, Zygomaturinae, and Palorchestinae. In 1977, Australian palaeontologist Michael Archer synonymised Nototheriinae with Diprotodontinae and in 1978, Archer and Australian palaeontologist Alan Bartholomai elevated Palorchestinae to family level as Palorchestidae

Palorchestidae is an extinct family of vombatiform marsupials whose members are sometimes referred to as marsupial tapirs due to the retracted nasal region of their skulls causing them to superficially resemble those of true tapirs. The idea tha ...

, leaving Diprotodontoidea with families Diprotodontidae and Palorchestidae; and Diprotodontidae with subfamilies Diprotodontinae and Zygomaturinae.

Below is the Diprotodontoidea family tree according to Australian palaeontologists Karen H. Black

Karen H. Black, born about 1970, is a palaeontologist at the University of New South Wales. Black is the leading author on research describing new families, genera and species of fossil mammals. She is interested in understanding faunal change ...

and Brian Mackness, 1999 (top), and Vombatiformes family tree according to Beck ''et al.'' 2020 (bottom):

Evolution

Diprotodontidae is the most diverse family in Vombatomorphia; it was better adapted to the spreading dry, open landscapes over the last tens of millions of years than other groups in the infraorder, living or extinct. ''Diprotodon'' has been found in every Australian state, making it the most-widespread Australian megafauna in the fossil record. The oldest vombatomorph (and vombatiform) is '' Mukupirna'', which was identified in 2020 from

Diprotodontidae is the most diverse family in Vombatomorphia; it was better adapted to the spreading dry, open landscapes over the last tens of millions of years than other groups in the infraorder, living or extinct. ''Diprotodon'' has been found in every Australian state, making it the most-widespread Australian megafauna in the fossil record. The oldest vombatomorph (and vombatiform) is '' Mukupirna'', which was identified in 2020 from Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

deposits of the South Australian Namba Formation

Namba (, ) is a district in Chūō and Naniwa wards of Osaka, Japan. It is regarded as the center of Osaka's ''Minami'' ( :ja:ミナミ, "South") region. Its name came from a variation of '' Naniwa'', the former name of Osaka. Namba hosts som ...

dating to 26–25 million years ago. The group probably evolved much earlier; ''Mukupirna'' was already differentiated as a closer relative to wombats than other vombatiformes, and attained a massive size of roughly , whereas the last common ancestor of vombatiformes was probably a small, creature.

Both diprotodontines and zygomaturines were both apparently quite diverse over the Late Oligocene

The Chattian is, in the geologic timescale

The geologic time scale or geological time scale (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the pro ...

to Early Miocene

The Early Miocene (also known as Lower Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene epoch (geology), Epoch made up of two faunal stage, stages: the Aquitanian age, Aquitanian and Burdigalian stages.

The sub-epoch lasted from 23.03 ± 0.05 annum, Ma to ...

, roughly 23 million years ago, though the familial and subfamilial classifications of diprotodontoids from this period is debated. Compared to zygomaturines, diprotodontines were rare during the Miocene, the only identified genus being ''Pyramios

''Pyramios'' is an extinct genus of diprotodont from the Miocene of Australia. It was very large, reaching a length of about 2.5 m (8.2 feet) and a height of about 1.5 m (4.92 feet). ''Pyramios'' is estimated to have weighed 700 kg (1102-15 ...

''. By the Late Miocene

The Late Miocene (also known as Upper Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene epoch (geology), Epoch made up of two faunal stage, stages. The Tortonian and Messinian stages comprise the Late Miocene sub-epoch, which lasted from 11.63 Ma (million ye ...

, diprotodontians became the commonest marsupial order in fossil sites, a dominance that endures to the present day; at this point, the most-prolific diprotodontians were diprotodontids and kangaroos. Diprotodontidae also began a gigantism

Gigantism (, ''gígas'', "wiktionary:giant, giant", plural γίγαντες, ''gígantes''), also known as giantism, is a condition characterized by excessive growth and height significantly above average height, average. In humans, this conditi ...

trend, along with several other marsupials, probably in response to the lower-quality plant foods available in a drying climate, requiring them to consume much more. Gigantism appears to have evolved independently six times among the vombatiform lineages. Diprotodontine diversity returned in the Pliocene; Diprotodontidae reached peak diversity with seven genera, coinciding with the spread of open forests. In 1977, Archer said ''Diprotodon'' directly evolved from the smaller '' Euryzygoma'', which has been discovered in Pliocene deposits of eastern Australia predating 2.5 million years ago.

In general, there is poor resolution on the ages of Australian fossil sites. While the geochronology

Geochronology is the science of Chronological dating, determining the age of rock (geology), rocks, fossils, and sediments using signatures inherent in the rocks themselves. Absolute geochronology can be accomplished through radioactive isotopes, ...

of ''Diprotodon'' is one of best for Australian megafauna, it is still incomplete and the majority of remains are undated. Price and Australian palaeontologist Katarzyna Piper reported the earliest, indirectly dated ''Diprotodon'' fossils from the Nelson Bay Formation at Nelson Bay, New South Wales

Nelson Bay is a significant township of the Port Stephens local government area in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia. It is located on a bay of the same name on the southern shore of Port Stephens about by road north-east of Ne ...

, which dates to 1.77 million to 780,000 years ago during the Early Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial epoch (geology), sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, representing the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently esti ...

. These remains are 8–17% smaller than those of Late Pleistocene ''Diprotodon'' but are otherwise indistinguishable. The oldest directly dated ''Diprotodon'' fossils come from the Boney Bite site at Floraville, New South Wales; they were deposited approximately 340,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, more widely known as the Middle Pleistocene (its previous informal name), is an Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale or a Stage (stratigraphy), stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocen ...

based on U-series dating U series or U-series may refer to:

Science and technology

* HTC U series, Android smartphones

* IdeaPad U series, Lenovo consumer laptop computers

* Sony U series

The Sony U series of subnotebook computers refers to two series of Sony products the ...

and luminescence dating

Luminescence dating refers to a group of chronological dating methods of determining how long ago mineral grains were last exposed to sunlight or sufficient heating. It is useful to geologists and archaeologists who want to know when such an event ...

of quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

and orthoclase

Orthoclase, or orthoclase feldspar ( endmember formula K Al Si3 O8), is an important tectosilicate mineral which forms igneous rock. The name is from the Ancient Greek for "straight fracture", because its two cleavage planes are at right angles ...

. Floraville is the only-identified Middle Pleistocene site in tropical northern Australia. Beyond these, almost all dated ''Diprotodon'' material comes from Marine Isotope Stage 5

Marine Isotope Stage 5 or MIS 5 is a marine isotope stage in the geologic temperature record, between 130,000 and 80,000 years ago. Sub-stage MIS 5e corresponds to the Last Interglacial, also called the Eemian (in Europe) or Sangamonian (in No ...

(MIS5) or younger—after 110,000 years ago during the Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as the Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division ...

.

Description

Skull

''Diprotodon'' has a long, narrow skull. Like other marsupials, the top of the skull of ''Diprotodon'' is flat or depressed over the smallbraincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan, or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calv ...

and the sinuses

Paranasal sinuses are a group of four paired air-filled spaces that surround the nasal cavity. The maxillary sinuses are located under the eyes; the frontal sinuses are above the eyes; the ethmoidal sinuses are between the eyes and the sphenoi ...

of the frontal bone

In the human skull, the frontal bone or sincipital bone is an unpaired bone which consists of two portions.'' Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bo ...

. Like many other giant vombatiformes, the frontal sinus

The frontal sinuses are one of the four pairs of paranasal sinuses that are situated behind the brow ridges. Sinuses are mucosa-lined airspaces within the bones of the face and skull. Each opens into the anterior part of the corresponding middle ...

es are extensive; in a specimen from Bacchus Marsh

Bacchus Marsh ( Wathawurrung: ''Pullerbopulloke'') is a town in Victoria, Australia, located approximately north-west of the state capital Melbourne, at a near equidistance to the major cities of Melbourne, Ballarat and Geelong.

As of the ...

, they take up —roughly 25% of skull volume—whereas the brain occupies —only 4% of the skull volume. Marsupials tend to have smaller brain-to-body mass ratios than placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguished ...

mammals, becoming more disparate the bigger the animal, which could be a response to a need to conserve energy because the brain is a calorically expensive organ, or is proportional to the maternal metabolic rate, which is much less in marsupials due to the shorter gestation period. The expanded sinuses increase the surface area available for the temporalis muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomatic a ...

to attach, which is important for biting and chewing, to compensate for a deflated braincase as a result of a proportionally smaller brain. They may also have helped dissipate stresses produced by biting more efficiently across the skull.

The occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...

, the back of the skull, slopes forward at 45 degrees unlike most modern marsupials, where it is vertical. The base of the occipital is significantly thickened. The occipital condyle

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the Atlas (anatomy), atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape ...

s, a pair of bones that connect the skull with the vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

, are semi-circular and the bottom half is narrower than the top. The inner border, which forms the foramen magnum

The foramen magnum () is a large, oval-shaped opening in the occipital bone of the skull. It is one of the several oval or circular openings (foramina) in the base of the skull. The spinal cord, an extension of the medulla oblongata, passes thro ...

where the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

feeds through, is thin and well-defined. The top margin of the foramen magnum is somewhat flattened rather than arched. The foramen expands backwards towards the inlet, especially vertically, and is more-reminiscent of a short neural canal

In the developing chordate (including vertebrates), the neural tube is the embryonic precursor to the central nervous system, which is made up of the brain and spinal cord. The neural groove gradually deepens as the neural folds become elevated, ...

—the tube running through a vertebral centrum where the spinal cord passes through—than a foramen magnum.

A sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

extends across the midline of the skull from the supraoccipital—the top of the occipital bone—to the region between the eyes on the top of the head. The orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

(eye socket) is small and vertically oval-shaped. The nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

s slightly curve upwards until near their endpoint, where they begin to curve down, giving the bones a somewhat S-shaped profile. Like many marsupials, most of the nasal septum

The nasal septum () separates the left and right airways of the Human nose, nasal cavity, dividing the two nostrils.

It is Depression (kinesiology), depressed by the depressor septi nasi muscle.

Structure

The fleshy external end of the nasal s ...

is made of bone rather than cartilage

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. Semi-transparent and non-porous, it is usually covered by a tough and fibrous membrane called perichondrium. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints ...

. The nose would have been quite mobile. The height of the skull from the peak of the occipital bone to the end of the nasals is strikingly almost uniform; the end of the nasals is the tallest point. The zygomatic arch

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of temporal bone, zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the ...

(cheek bone) is strong and deep as in kangaroos but unlike those of koalas and wombats, and extends all the way from the supraoccipital.

Jaws

As in kangaroos and wombats, there is a gap between the jointing of thepalate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sep ...

(roof of the mouth) and the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

(upper jaw) behind the last molar, which is filled by the medial pterygoid plate

The pterygoid processes of the sphenoid (from Greek ''pteryx'', ''pterygos'', "wing"), one on either side, descend perpendicularly from the regions where the body and the greater wings of the sphenoid bone unite.

Each process consists of a med ...

. This would have been the insertion

Insertion may refer to:

*Insertion (anatomy), the point of a tendon or ligament onto the skeleton or other part of the body

*Insertion (genetics), the addition of DNA into a genetic sequence

*Insertion, several meanings in medicine, see ICD-10-PCS

...

for the medial pterygoid muscle

The medial pterygoid muscle (or internal pterygoid muscle) is a thick, quadrilateral muscle of the face. It is supplied by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (V). It is important in mastication (chewing).

Structure

The medial pter ...

that was involved in closing the jaw. Like many grazers, the masseter muscle

In anatomy, the masseter is one of the muscles of mastication. Found only in mammals, it is particularly powerful in herbivores to facilitate chewing of plant matter. The most obvious muscle of mastication is the masseter muscle, since it is the ...

, which is also responsible for closing the jaw, seems to have been the dominant jaw muscle. A probable large temporal muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomatic ...

compared to the lateral pterygoid muscle

The lateral pterygoid muscle (or external pterygoid muscle) is a muscle of mastication. It has two heads. It lies superior to the medial pterygoid muscle. It is supplied by pterygoid branches of the maxillary artery, and the lateral pterygoid n ...

may indicate, unlike in wombats, a limited range of side-to-side jaw motion means ''Diprotodon'' would have been better at crushing rather than grinding food. The insertion of the masseter is placed forwards, in front of the orbits, which could have allowed better control over the incisors. ''Diprotodon'' chewing strategy appears to align more with kangaroos than wombats: a powerful vertical crunch was followed by a transverse grinding motion.

As in other marsupials, the ramus of the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone ...

, the portion that goes up to connect with the skull, angles inward. The condyloid process

The condyloid process or condylar process is the process on the human and other mammalian species' mandibles that ends in a condyle, the mandibular condyle. It is thicker than the coronoid process of the mandible and consists of two portions: the ...

, which connects the jaw to the skull, is similar to that of a koala. The ramus is straight and extends almost vertically, thickening as it approaches the body of the mandible where the teeth are. The depth of the body of the mandible increases from the last molar to the first. The strong mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis (Latin: ''symphysis menti'') or line of junction where the two lateral ha ...

, which fuses the two halves of the mandible, begins at the front-most end of the third molar; this would prevent either half of the mandible from moving independently of the other, unlike in kangaroos which use this ability to better control their incisors.

Teeth

The

The dental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of ''Diprotodon'' is . In each half of either jaw are three incisors in the upper jaw and one in the lower jaw; there are one premolar

The premolars, also called premolar Tooth (human), teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the Canine tooth, canine and Molar (tooth), molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per dental terminology#Quadrant, quadrant in ...

and four molars in both jaws but no canines. A long diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

(gap) separates the incisors from the molars.

The incisors are scalpriform (chisel-like). Like those of wombats and rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s, the first incisors in both jaws continuously grew throughout the animal's life but the other two upper incisors did not. This combination is not seen in any living marsupial. The cross-section of the upper incisors is circular. In one old male specimen, the first upper incisor measures of which is within the tooth socket; the second is and is in the socket; and the exposed part of the third is . The first incisor is convex and curves outwards but the other two are concave. The lower incisor has a faint upward curve but is otherwise straight and has an oval cross-section. In the same old male specimen, the lower incisor measures , of which is inside the socket.

The premolars and molars are bilophodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone toot ...

, each having two distinct lophs (ridges). The premolar is triangular and about half the size of the molars. As in kangaroos, the necks of the lophs are coated in cementum

Cementum is a specialized calcified substance covering the root of a tooth. The cementum is the part of the periodontium that attaches the teeth to the alveolar bone by anchoring the periodontal ligament.

Structure

The cells of cementum are ...

. Unlike in kangaroos, there is no connecting ridge between the lophs. The peaks of these lophs have a thick enamel coating that thins towards the base; this could wear away with use and expose the dentine

Dentin ( ) (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) () is a calcified tissue of the body and, along with enamel, cementum, and pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It is usually covered by enamel on the crown ...

layer, and beneath that osteodentine. Like the first premolar of other marsupials, the first molar of ''Diprotodon'' and wombats is the only tooth that is replaced. ''D. optatum'' premolars were highly morphologically variable even within the same individual.

Vertebrae

''Diprotodon'' had seven cervical (neck) vertebrae. Theatlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

, the first cervical (C1), has a pair of deep cavities for insertion of the occipital condyles. The diaphophyses of the atlas, an upward-angled projection on either the side of the vertebra, are relatively short and thick, and resemble those of wombats and koalas. The articular surface of the axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

(C2), the part that joints to another vertebra, is slightly concave on the front side and flat on the back side. As in kangaroos, the axis has a low subtriangular hypophysis projecting vertically from the underside of the vertebra and a proportionally long odontoid—a projection from the axis which fits into the atlas—but the neural spine, which projects vertically the topside of the vertebra, is more forwards. The remaining cervicals lack a hypophysis. As in kangaroos, C3 and C4 have a shorter and more-compressed neural spine, which is supported by a low ridge along its midline in the front and the back. The neural spine of C5 is narrower but thicker, and is supported by stronger-but-shorter ridges. C7 had a forked shape on top of the neural spine.

''Diprotodon'' probably had 13 dorsal vertebra

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebrae of intermediate size between the cervical and lumbar ve ...

e and 14 pairs of closely spaced rib

In vertebrate anatomy, ribs () are the long curved bones which form the rib cage, part of the axial skeleton. In most tetrapods, ribs surround the thoracic cavity, enabling the lungs to expand and thus facilitate breathing by expanding the ...

s. Like many other mammals, the dorsals initially decrease in breadth and then expand before connecting to the lumbar vertebra

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe the ...

e. Unusually, the front dorsals match the short proportions of the cervicals, and the articular surface is flat. At the beginning of the series, the neural spine is broad and angled forward, and is also supported by a low ridge along its midline in the front and the back. In later examples, the neural spine is angled backwards and bifurcates (splits into two). Among mammals, bifurcation of the neural spine is only seen in elephants and humans, and only in a few of the cervicals and not in the dorsals. Compared to those of wombats and kangaroos, the neural arch is proportionally taller. As in elephants, the epiphysial plate

The epiphyseal plate, epiphysial plate, physis, or growth plate is a hyaline cartilage plate in the metaphysis at each end of a long bone. It is the part of a long bone where new bone growth takes place; that is, the whole bone is alive, with ma ...

s (growth plates) and the neural arch, to which the neural spine is attached, are anchylosed—very rigid in regard to the vertebral centrum—which served to support the animal's immense weight.

Like most marsupials, ''Diprotodon'' likely had six lumbar vertebrae. They retain a proportionally tall neural arch but not the diapophyses, though L1 can retain a small protuberance on one side where a diapophysis would be in a dorsal vertebra; this has been documented in kangaroos and other mammals. The length of each vertebra increases along the series so the lumbar series may have bent downward.

Like other marsupials, ''Diprotodon'' had two sacral vertebrae

The sacrum (: sacra or sacrums), in human anatomy, is a triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part of the pelvic cavity, ...

. The base of the neural spines of these two were ossified

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes resulting in t ...

(fused) together.

Limbs

Girdles

The general proportions of thescapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

(shoulder blade) align more closely with more-basal vertebrates such as monotreme

Monotremes () are mammals of the order Monotremata. They are the only group of living mammals that lay eggs, rather than bearing live young. The extant monotreme species are the platypus and the four species of echidnas. Monotremes are typified ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s, and fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

rather than marsupials and placental mammal

Placental mammals ( infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguish ...

s. It is triangular and proportionally narrow but unlike most mammals with a triangular scapula, the arm attaches to top of the scapula and the subspinous fossa (the fossa, a depression below the spine of the scapula

The spine of the scapula or scapular spine is a prominent plate of bone, which crosses obliquely the medial four-fifths of the scapula at its upper part, and separates the supra- from the infraspinatous fossa.

Structure

It begins at the vertica ...

) becomes bigger towards the arm joint rather than decreasing. The glenoid cavity

The glenoid fossa of the scapula or the glenoid cavity is a bone part of the shoulder. The word ''glenoid'' is pronounced or (both are common) and is from , "socket", reflecting the shoulder joint's ball-and-socket form. It is a shallow, pyri ...

where the arm connects is oval shaped as in most mammals.

Unlike other marsupials, the ilia, the large wings of the pelvis

The pelvis (: pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of an Anatomy, anatomical Trunk (anatomy), trunk, between the human abdomen, abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also c ...

, are lamelliform (short and broad, with a flat surface instead of an iliac fossa

The iliac fossa is a large, smooth, concave surface on the internal surface of the Ilium (bone), ilium (part of the three fused bones making the hip bone).

Structure

The iliac fossa is bounded above by the iliac crest, and below by the Arcuate ...

). Lamelliform ilia have only been recorded in elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

s, sloth

Sloths are a Neotropical realm, Neotropical group of xenarthran mammals constituting the suborder Folivora, including the extant Arboreal locomotion, arboreal tree sloths and extinct terrestrial ground sloths. Noted for their slowness of move ...

s, and ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a superfamily of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and Europe in prehistory, and counting humans are found global ...

s, though these groups all have a much-longer sacral vertebra series whereas marsupials are restricted to two sacral vertebrae. The ilia provided strong muscle attachments that were probably oriented and used much the same as those in an elephant. The sacroiliac joint

The sacroiliac joint or SI joint (SIJ) is the joint between the sacrum and the ilium bones of the pelvis, which are connected by strong ligaments. In humans, the sacrum supports the spine and is supported in turn by an ilium on each side. The ...

where the pelvis connects to the spine is at 35 degrees in reference to the long axis of the ilium. The ischia

Ischia ( , , ) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about from the city of Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Although inhabited since the Bronze Age, as a Ancient G ...

, which form part of the hip socket, are thick and rounded tailwards but taper and diverge towards the socket, unlike those in kangaroos, where the ischia proceed almost parallel to each other. They were not connected to the vertebra. The hip socket itself is well-rounded and almost hemispherical.

Long bones

Unlike those of most marsupials, the humerus of ''Diprotodon'' is almost straight rather than S-shaped, and thetrochlea of the humerus

In the human arm, the humeral trochlea is the medial portion of the articular surface of the elbow joint which articulates with the trochlear notch on the ulna in the forearm.

Structure

In humans and other apes, it is trochleariform (or trochlei ...

at the elbow joint is not perforated. The ridges for muscle attachments are poorly developed, which seems to have been compensated for by the powerful forearms. Similarly, the condyles where the radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

and ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

(the forearm bones) connect maintain their rounded shape and are quite-similarly sized, and unusually reminiscent of the condyles between the femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

and the tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

and fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

in the leg of a kangaroo.

Like elephants, the femur of ''Diprotodon'' is straight and compressed anteroposteriorly (from headside to tailside). The walls of the femur are prodigiously thickened, strongly constricting the medullary cavity

The medullary cavity (''medulla'', innermost part) is the central cavity of bone shafts where red bone marrow and/or yellow bone marrow (adipose tissue) is stored; hence, the medullary cavity is also known as the marrow cavity.

Located in the ma ...

where the bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid biological tissue, tissue found within the Spongy bone, spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It i ...

is located. The proximal end (part closest to the hip joint) is notably long, broad, and deep. The femoral head

The femoral head (femur head or head of the femur) is the highest part of the thigh bone (femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the ...

projects up far from the greater trochanter

The greater trochanter of the femur is a large, irregular, quadrilateral eminence and a part of the skeletal system.

It is directed lateral and medially and slightly posterior. In the adult it is about 2–4 cm lower than the femoral head.Sta ...

. As in kangaroos, the greater trochanter is split into two lobes. The femoral neck

The femoral neck (also femur neck or neck of the femur) is a flattened pyramidal process of bone, connecting the femoral head with the femoral shaft, and forming with the latter a wide angle opening medialward.

Structure

The neck is flattene ...

is roughly the same diameter as the femoral head. Also as in kangaroos, the condyle for the fibula is excavated out but the condyle for the tibia is well-rounded and hemispherical. Like those of many other marsupials, the tibia is twisted and the tibial malleolus

A malleolus is the bony prominence on each side of the human ankle.

Each leg is supported by two bones, the tibia on the inner side (medial) of the leg and the fibula on the outer side (lateral) of the leg. The medial malleolus is the promin ...

(on the ankle) is reduced.

Paws

''Diprotodon'' has five digits on either paw. Like otherplantigrade

151px, Portion of a human skeleton, showing plantigrade habit

In terrestrial animals, plantigrade locomotion means walking with the toes and metatarsals flat on the ground. It is one of three forms of locomotion adopted by terrestrial mammals. ...

walkers, where the paws were flat on the ground, the wrist and ankle would have been largely rigid and inflexible. The digits are proportionally weak so the paws probably had a lot of padding. Similarly, the digits do not seem to have been much engaged in weight bearing.

The forepaw was strong and the shape of the wrist bones is quite similar to those of kangaroos. Like other vombatiformes, the metacarpal

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones ( wrist bones), which articulate ...

s, which connect the fingers to the wrist, are broadly similar to those of kangaroos and allies. The enlarged pisiform bone

The pisiform bone ( or ), also spelled pisiforme (from the Latin ''pisiformis'', pea-shaped), is a small knobbly, sesamoid bone that is found in the wrist. It forms the ulnar border of the carpal tunnel.

Structure

The pisiform is a sesamoid bone ...

takes up half the jointing surface of the ulna. The fifth digit on the forepaw is the largest.

The digits of the hindpaws turn inwards from the ankle at 130 degrees. The second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

and third metatarsals (the metatarsal

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

s connect the toes to the ankle) are significantly reduced, which may mean these digits were syndactylous (fused) like those of all modern diprotodontians. The first, fourth, and fifth digits are enlarged. The toes are each about the same length, except the fifth which is much stouter.

Size

''Diprotodon'' is the largest-known marsupial to ever have lived. In life, adult ''Diprotodon'' could have reached at the shoulders and from head to tail. Accounting for cartilaginousintervertebral disc

An intervertebral disc (British English), also spelled intervertebral disk (American English), lies between adjacent vertebrae in the vertebral column. Each disc forms a fibrocartilaginous joint (a symphysis), to allow slight movement of the ver ...

s, ''Diprotodon'' may have been 20% longer than reconstructed skeletons, exceeding .

As researchers were formulating predictive body-mass equations for fossil species, efforts were largely constrained to eutherian

Eutheria (from Greek , 'good, right' and , 'beast'; ), also called Pan-Placentalia, is the clade consisting of placental mammals and all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials.

Eutherians are distingu ...

mammals rather than marsupials. The first person to attempt to estimate the living weight of ''Diprotodon'' was Peter Murray in his 1991 review of the megafauna of Pleistocene Australia; Murray made an estimate of using cranial and dental measurements, which he said was probably not a very precise figure. This made ''Diprotodon'' the largest herbivore in Australia. In 2001, Canadian biologist Gary Burness and colleagues did a linear regression

In statistics, linear regression is a statistical model, model that estimates the relationship between a Scalar (mathematics), scalar response (dependent variable) and one or more explanatory variables (regressor or independent variable). A mode ...

between the largest herbivores and carnivores—living or extinct—from every continent (for Australia: ''Diprotodon'', ''Varanus priscus

Megalania (''Varanus priscus'') is an extinct species of giant monitor lizard, part of the megafaunal assemblage that inhabited Australia during the Pleistocene. It is the largest terrestrial lizard known to have existed, but the fragmentary na ...

'', and ''Thylacoleo carnifex

''Thylacoleo'' ("pouch lion") is an extinct genus of carnivorous marsupials that lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene (until around 40,000 years ago), often known as marsupial lions. They were the largest and last mem ...

'') against the landmass area of their continent, and another regression between the daily food intake of living creatures against the landmass of their continents. He calculated the food requirement of ''Diprotodon'' was 50–60% smaller than expected for Australia's landmass, which he believed was a result of a generally lower metabolism in marsupials compared to placentals—up to 20% lower—and sparser nutritious vegetation than other continents. The maximum-attainable body size is capped much lower than those for other continents.

In 2003, Australian palaeontologist Stephen Wroe and colleagues took a more-sophisticated approach to body mass than Murray's estimate. They made a regression between the minimum circumference of the femora and humeri of 18 quadrupedal marsupials and 32 placentals against body mass, and then inputted 17 ''Diprotodon'' long bones into their predictive model. The results ranged from , for a mean of , though Wroe said reconstructing the weight of extinct creatures that far outweighed living counterparts is problematic. For comparison, an American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison''; : ''bison''), commonly known as the American buffalo, or simply buffalo (not to be confused with Bubalina, true buffalo), is a species of bison that is endemic species, endemic (or native) to North America. ...

they used in their study weighed and a hippo weighed .

Paleobiology

Diet

Like modern megaherbivores, most evidently the

Like modern megaherbivores, most evidently the African elephant

African elephants are members of the genus ''Loxodonta'' comprising two living elephant species, the African bush elephant (''L. africana'') and the smaller African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''). Both are social herbivores with grey skin. ...

, Pleistocene Australian megafauna likely had a profound effect on the vegetation, limiting the spread of forest cover and woody plants. Carbon isotope analysis suggests ''Diprotodon'' fed on a broad range of foods and, like kangaroos, was consuming both C3—well-watered trees, shrubs, and grasses—and C4 plants—arid grasses, a finding replicated by calcium isotope analysis showing ''Diprotodon'' to have been a mixed feeder. Carbon isotope analyses on ''Diprotodon'' excavated from the Cuddie Springs site in unit

Unit may refer to:

General measurement

* Unit of measurement, a definite magnitude of a physical quantity, defined and adopted by convention or by law

**International System of Units (SI), modern form of the metric system

**English units, histo ...

s SU6 (possibly 45,000 years old) and SU9 (350,000 to 570,000 years old) indicate ''Diprotodon'' adopted a somewhat-more-varied seasonal diet as Australia's climate dried but any change was subtle. In contrast, contemporary kangaroos and wombats underwent major dietary shifts or specialisations towards, respectively, C3 and C4 plants. The fossilised, incompletely digested gut contents of one 53,000-year-old individual from Lake Callabonna

Lake Callabonna is a dry salt lake with little to no vegetation located in the Far North region of South Australia. The lake is situated approximately southwest of Cameron Corner, the junction of South Australia, Queensland and New South Wal ...

show its last meal consisted of young leaves, stalks, and twigs.

The molars of ''Diprotodon'' are a simple bilophodont shape. Kangaroos use their bilophodont teeth to grind tender, low-fibre plants as a browser as well as grass as a grazer. Kangaroos that predominantly graze have specialised molars to resist the abrasiveness of grass but such adaptations are not exhibited in ''Diprotodon'', which may have had a mixed diet similar to that of a browsing wallaby

A wallaby () is a small or middle-sized Macropodidae, macropod native to Australia and New Guinea, with introduced populations in New Zealand, Hawaii, the United Kingdom and other countries. They belong to the same Taxonomy (biology), taxon ...

. It may also have chewed like wallabies, beginning with a vertical crunch before grinding transversely, as opposed to wombats, which only grind transversely. Similarly to many large ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s (hoofed mammals), the jaws of ''Diprotodon'' were better suited for crushing rather than grinding, which would have permitted it to process vegetation in bulk.

In 2016, Australian biologists Alana Sharpe and Thomas Rich estimated the maximum-possible bite force

Bite force quotient (BFQ) is a numerical value commonly used to represent the bite force of an animal adjusted for its body mass, while also taking factors like the allometry effects.

The BFQ is calculated as the regression of the quotient of an ...

of ''Diprotodon'' using finite element analysis

Finite element method (FEM) is a popular method for numerically solving differential equations arising in engineering and mathematical models, mathematical modeling. Typical problem areas of interest include the traditional fields of structural ...