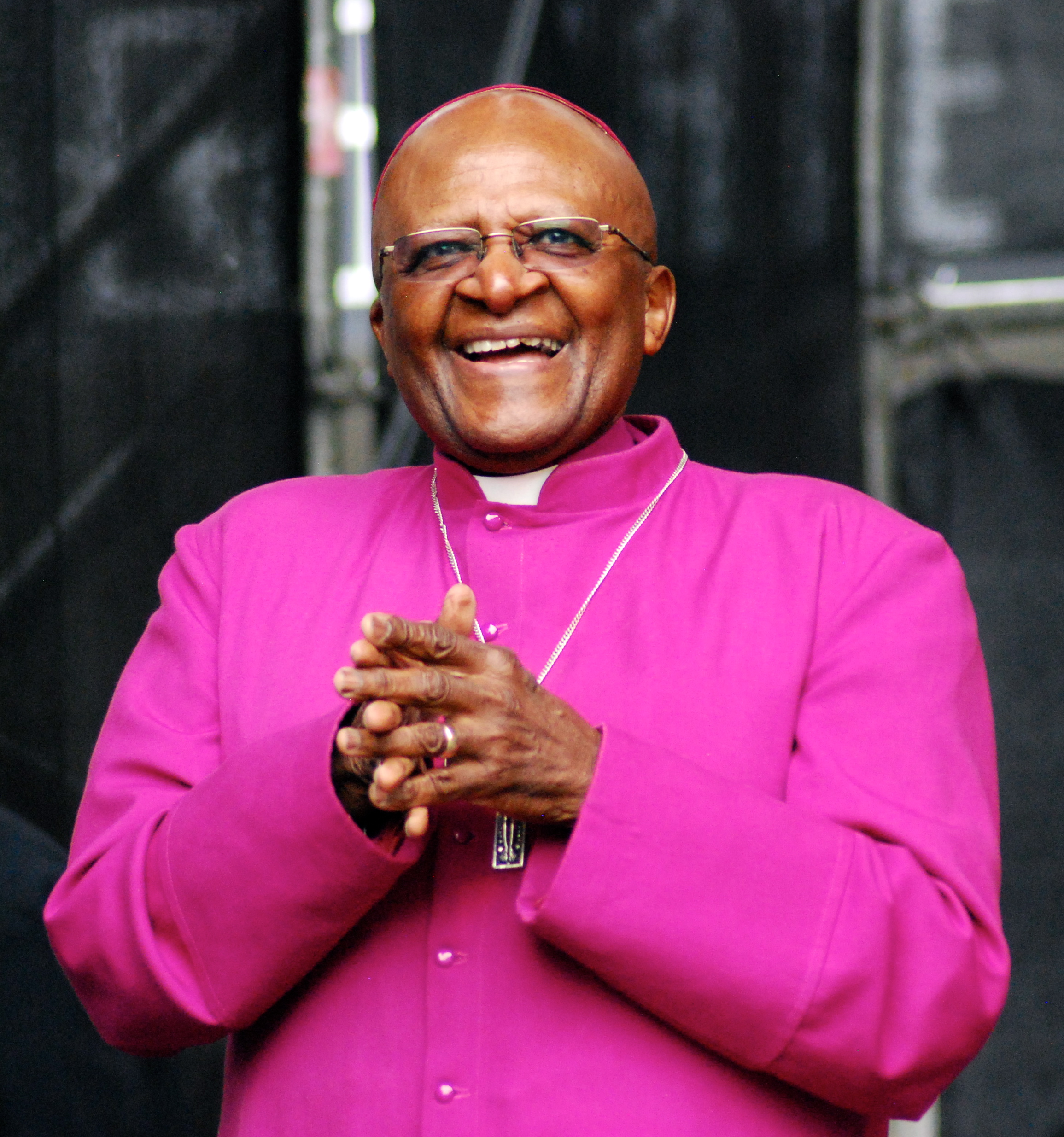

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

n

Anglican bishop and

theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

, known for his work as an

anti-apartheid and

human rights activist. He was

Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then

Archbishop of Cape Town from 1986 to 1996, in both cases being the first Black African to hold the position. Theologically, he sought to fuse ideas from

Black theology with

African theology.

Tutu was born of mixed

Xhosa and

Motswana heritage to a poor family in

Klerksdorp,

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. Entering adulthood, he trained as a teacher and married

Nomalizo Leah Tutu, with whom he had several children. In 1960, he was ordained as an Anglican priest and in 1962 moved to the United Kingdom to study theology at

King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

. In 1966 he returned to southern Africa, teaching at the

Federal Theological Seminary and then the

University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. In 1972, he became the Theological Education Fund's director for Africa, a position based in London but necessitating regular tours of the African continent. Back in southern Africa in 1975, he served first as

dean of

St Mary's Cathedral in

Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

and then as

Bishop of Lesotho; from 1978 to 1985 he was general-secretary of the

South African Council of Churches. He emerged as one of the most prominent opponents of South Africa's

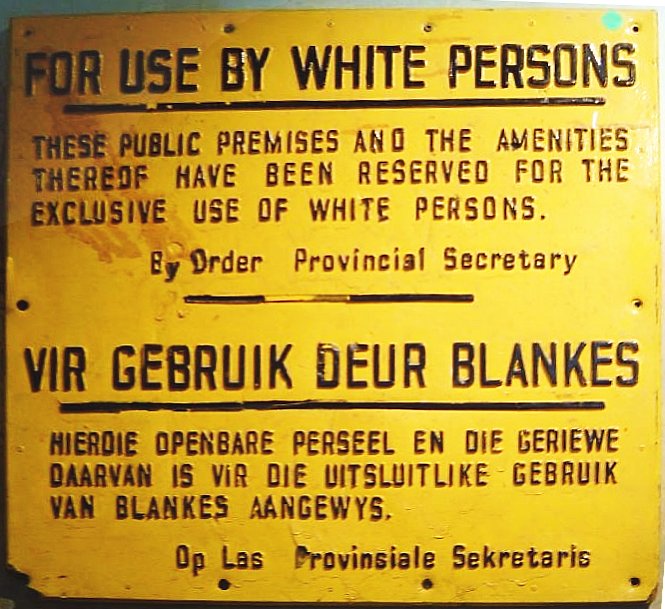

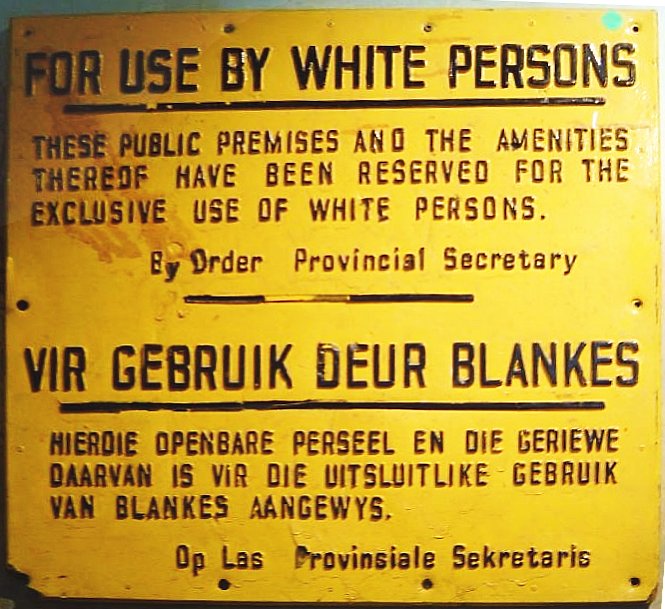

apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

system of

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

and

white minority rule. Although warning the

National Party government that anger at apartheid would lead to racial violence, as an activist he stressed

non-violent protest and foreign economic pressure to bring about

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

.

In 1985, Tutu became

Bishop of Johannesburg and in 1986 the Archbishop of Cape Town, the most senior position in southern Africa's Anglican hierarchy. In this position, he emphasised a consensus-building model of leadership and oversaw the

introduction of female priests. Also in 1986, he became president of the

All Africa Conference of Churches, resulting in further tours of the continent. After President

F. W. de Klerk released the anti-apartheid activist

Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990 and the pair led negotiations to end apartheid and introduce multi-racial democracy, Tutu assisted as a mediator between rival black factions. After the

1994 general election resulted in a

coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

headed by Mandela, the latter selected Tutu to chair the

Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate past human rights abuses committed by both pro and anti-apartheid groups. Following apartheid's fall, Tutu campaigned for

gay rights and spoke out on a wide range of subjects, among them his criticism of South African presidents

Thabo Mbeki

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki (; born 18 June 1942) is a South African politician who served as the 2nd democratic president of South Africa from 14 June 1999 to 24 September 2008, when he resigned at the request of his party, the African National Cong ...

and

Jacob Zuma

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma (; born 12 April 1942) is a South African politician who served as the fourth president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018. He is also referred to by his initials JZ and clan names Nxamalala and Msholozi. Zuma was a for ...

, his

opposition to the Iraq War, and describing

Israel's treatment of Palestinians as apartheid. In 2010, he retired from public life, but continued to speak out on numerous topics and events.

As Tutu rose to prominence in the 1970s, different socio-economic groups and political classes held a wide range of views about him, from critical to admiring. He was popular among South Africa's black majority and was internationally praised for his work involving anti-apartheid activism, for which he won the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

and other international awards. He also compiled several books of his speeches and sermons.

Early life

Childhood: 1931–1950

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born on 7 October 1931 in

Klerksdorp,

Transvaal, South Africa. His mother, Allen Dorothea Mavoertsek Mathlare, was born to a

Motswana family in

Boksburg. His father, Zachariah Zelilo Tutu, was from the

amaFengu branch of

Xhosa and grew up in

Gcuwa, Eastern Cape. At home, the couple spoke the

Xhosa language. Having married in Boksburg, they moved to Klerksdorp in the late 1950s, living in the city's "native location", or black residential area, since renamed Makoeteng. Zachariah worked as the principal of a

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

primary school and the family lived in the mud-brick schoolmaster's house in the yard of the Methodist mission.

The Tutus were poor; describing his family, Tutu later related that "although we weren't affluent, we were not destitute either". He had an older sister, Sylvia Funeka, who called him "Mpilo" (meaning 'life'). He was his parents' second son; their firstborn boy, Sipho, had died in infancy. Another daughter, Gloria Lindiwe, was born after him. Tutu was sickly from birth;

polio atrophied his right hand, and on one occasion he was hospitalised with serious burns. Tutu had a close relationship with his father, although angered at the latter's heavy drinking and violence toward his wife. The family were initially Methodists and Tutu was

baptised into the

Methodist Church in June 1932. They subsequently changed denominations, first to the

African Methodist Episcopal Church and then to the

Anglican Church.

In 1936, the family moved to

Tshing, where Zachariah became principal of a Methodist school. There, Tutu started his primary education, learned

Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

, and became the server at St Francis Anglican Church. He developed a love of reading, particularly enjoying comic books and European

fairy tales. In Tshing his parents had a third son, Tamsanqa, who also died in infancy. Around 1941, Tutu's mother moved to the

Witwatersrand to work as a cook at

Ezenzeleni Blind Institute in Johannesburg. Tutu joined her in the city, living in

Roodepoort West. In Johannesburg, he attended a Methodist primary school before transferring to the Swedish Boarding School (SBS) in the

St Agnes Mission. Several months later, he moved with his father to

Ermelo,

eastern Transvaal. After six months, the duo returned to Roodepoort West, where Tutu resumed his studies at SBS. Aged 12, he underwent

confirmation at St Mary's Church, Roodepoort.

Tutu entered the Johannesburg Bantu High School (Madibane High School) in 1945, where he excelled academically. Joining a school

rugby team, he developed a lifelong love of the sport. Outside of school, he earned money selling oranges and as a

caddie for white

golfers. To avoid the expense of a daily train commute to school, he briefly lived with family nearer to Johannesburg, before moving back in with his parents when they relocated to

Munsieville. He then returned to Johannesburg, moving into an Anglican hostel near the Church of Christ the King in

Sophiatown. He became a server at the church and came under the influence of its priest,

Trevor Huddleston; later biographer

Shirley du Boulay suggested that Huddleston was "the greatest single influence" in Tutu's life. In 1947, Tutu contracted

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

and was hospitalised in

Rietfontein for 18 months, during which he was regularly visited by Huddleston. In the hospital, he underwent

circumcision to mark his transition to manhood. He returned to school in 1949 and took his national exams in late 1950, gaining a second-class pass.

College and teaching career: 1951–1955

Although Tutu secured admission to study medicine at the

University of the Witwatersrand

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (), commonly known as Wits University or Wits, is a multi-campus Public university, public research university situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg, South Africa. The universit ...

, his parents could not afford the tuition fees. Instead, he turned toward teaching, gaining a government scholarship for a course at

Pretoria Bantu Normal College, a teacher training institution, in 1951. There, he served as treasurer of the Student Representative Council, helped to organise the Literacy and Dramatic Society, and chaired the Cultural and Debating Society. During one debating event he met the lawyer—and future president of South Africa—

Nelson Mandela; they would not encounter each other again until 1990. At the college, Tutu attained his Transvaal Bantu Teachers Diploma, having gained advice about taking exams from the activist

Robert Sobukwe. He had also taken five correspondence courses provided by the

University of South Africa (UNISA), graduating in the same class as future Zimbabwean leader

Robert Mugabe.

In 1954, Tutu began teaching English at Madibane High School; the following year, he transferred to the Krugersdorp High School, where he taught English and history. He began courting Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, a friend of his sister Gloria who was studying to become a primary school teacher. They were legally married at Krugersdorp Native Commissioner's Court in June 1955, before undergoing a

Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

wedding ceremony at the Church of Mary Queen of Apostles; although an Anglican, Tutu agreed to the ceremony due to Leah's Roman Catholic faith. The newlyweds lived at Tutu's parental home before renting their own six months later. Their first child, Trevor, was born in April 1956; a daughter, Thandeka, appeared 16 months later. The couple worshipped at St Paul's Church, where Tutu volunteered as a Sunday school teacher, assistant choirmaster, church councillor, lay preacher, and sub-deacon; he also volunteered as a football administrator for a local team.

Joining the clergy: 1956–1966

In 1953, the white-minority

National Party government introduced the

Bantu Education Act to further their

apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

system of racial segregation and white domination. Disliking the Act, Tutu and his wife left the teaching profession. With Huddleston's support, Tutu chose to become an Anglican priest. In January 1956, his request to join the Ordinands Guild was turned down due to his debts; these were then paid off by the wealthy industrialist

Harry Oppenheimer. Tutu was admitted to

St Peter's Theological College in

Rosettenville, Johannesburg, which was run by the Anglican

Community of the Resurrection. The college was residential, and Tutu lived there while his wife trained as a nurse in

Sekhukhuneland; their children lived with Tutu's parents in

Munsieville. In August 1960, his wife gave birth to another daughter, Naomi.

At the college, Tutu studied the Bible, Anglican doctrine, church history, and Christian ethics, earning a

Licentiate of Theology degree, and winning the archbishop's annual essay prize. The college's principal, Godfrey Pawson, wrote that Tutu "has exceptional knowledge and intelligence and is very industrious. At the same time, he shows no arrogance, mixes in well, and is popular ... He has obvious gifts of leadership." During his years at the college, there had been an intensification in anti-apartheid activism as well as a crackdown against it, including the

Sharpeville massacre of 1960. Tutu and the other trainees did not engage in anti-apartheid campaigns; he later noted that they were "in some ways a very apolitical bunch".

In December 1960,

Edward Paget ordained Tutu as an Anglican priest at

St Mary's Cathedral. Tutu was then appointed assistant curate in St Alban's Parish,

Benoni, where he was reunited with his wife and children, and earned two-thirds of what his white counterparts were given. In 1962, Tutu was transferred to St Philip's Church in

Thokoza, where he was placed in charge of the congregation and developed a passion for pastoral ministry. Many in South Africa's white-dominated Anglican establishment felt the need for more black Africans in positions of ecclesiastical authority; to assist in this, Aelfred Stubbs proposed that Tutu train as a theology teacher at

King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

(KCL). Funding was secured from the

International Missionary Council's Theological Education Fund (TEF), and the government agreed to give the Tutus permission to move to Britain. They duly did so in September 1962.

At KCL, Tutu studied under theologians like

Dennis Nineham,

Christopher Evans,

Sydney Evans,

Geoffrey Parrinder, and

Eric Mascall. In London, the Tutus felt liberated experiencing a life free from South Africa's apartheid and

pass laws; he later noted that "there is racism in England, but we were not exposed to it". He was also impressed by the

freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

in the country, especially at

Speakers' Corner in London's

Hyde Park. The family moved into the curate's flat behind the Church of St Alban the Martyr in

Golders Green, where Tutu assisted Sunday services, the first time that he had ministered to a white congregation. It was in the flat that a daughter,

Mpho Andrea Tutu, was born in 1963. Tutu was academically successful and his tutors suggested that he convert to an

honours degree

Honours degree has various meanings in the context of different degrees and education systems. Most commonly it refers to a variant of the undergraduate bachelor's degree containing a larger volume of material or a higher standard of study, ...

, which entailed his also studying

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

. He received his degree from

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in a ceremony held at the

Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London, England. It has a seating capacity of 5,272.

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres ...

.

Tutu then secured a TEF grant to study for a master's degree, doing so from October 1965 until September 1966, completing his dissertation on

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

in West Africa. During this period, the family moved to

Bletchingley in Surrey, where Tutu worked as the assistant curate of St Mary's Church. In the village, he encouraged cooperation between his Anglican parishioners and the local Roman Catholic and Methodist communities. Tutu's time in London helped him to jettison any bitterness to whites and feelings of racial inferiority; he overcame his habit of automatically deferring to whites.

Career during apartheid

Teaching in South Africa and Lesotho: 1966–1972

In 1966, Tutu and his family moved to

East Jerusalem, where he studied

Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

and Greek for two months at

St George's College. They then returned to South Africa, settling in

Alice in 1967. The

Federal Theological Seminary (Fedsem) had recently been established there as an amalgamation of training institutions from different Christian denominations. At Fedsem, Tutu was employed teaching doctrine, the

Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

, and Greek; Leah became its library assistant. Tutu was the college's first black staff-member, and the campus allowed a level of racial-mixing which was rare in South Africa. The Tutus sent their children to a private boarding school in Swaziland, thereby keeping them from South Africa's Bantu Education syllabus.

Tutu joined a pan-Protestant group, the Church Unity Commission, served as a delegate at Anglican-Catholic conversations, and began publishing in

academic journal

An academic journal (or scholarly journal or scientific journal) is a periodical publication in which Scholarly method, scholarship relating to a particular academic discipline is published. They serve as permanent and transparent forums for the ...

s. He also became the Anglican chaplain to the neighbouring

University of Fort Hare; in an unusual move for the time, Tutu invited female as well as male students to become servers during the

Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

. He joined student delegations to meetings of the Anglican Students' Federation and the University Christian Movement, and was broadly supportive of the

Black Consciousness Movement that emerged from South Africa's 1960s student milieu, although did not share its view on avoiding collaboration with whites. In August 1968, he gave a sermon comparing South Africa's situation with that in the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

, likening anti-apartheid protests to the recent

Prague Spring. In September, Fort Hare students held a sit-in protest over the university administration's policies; after they were surrounded by police with

dogs, Tutu waded into the crowd to pray with the protesters. This was the first time that he had witnessed state power used to suppress dissent.

In January 1970, Tutu left the seminary for a teaching post at the

University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland (UBLS) in

Roma, Lesotho. This brought him closer to his children and offered twice the salary he earned at Fedsem. He and his wife moved to the UBLS campus; most of his fellow staff members were white expatriates from the US or Britain. As well as his teaching position, he also became the college's Anglican chaplain and the warden of two student residences. In Lesotho, he joined the executive board of the Lesotho Ecumenical Association and served as an

external examiner for both Fedsem and

Rhodes University. He returned to South Africa on several occasions, including to visit his father shortly before the latter's death in February 1971.

TEF Africa director: 1972–1975

Tutu accepted TEF's offer of a job as their director for Africa, a position based in England. South Africa's government initially refused permission, regarding him with suspicion since the Fort Hare protests, but relented after Tutu argued that his taking the role would be good publicity for South Africa. In March 1972, he returned to Britain. The TEF's headquarters were in

Bromley

Bromley is a large town in Greater London, England, within the London Borough of Bromley. It is southeast of Charing Cross, and had an estimated population of 88,000 as of 2023.

Originally part of Kent, Bromley became a market town, charte ...

, with the Tutu family settling in nearby

Grove Park, where Tutu became honorary curate of St Augustine's Church.

Tutu's job entailed assessing grants to theological training institutions and students. This required his touring Africa in the early 1970s, and he wrote accounts of his experiences. In

Zaire, he for instance lamented the widespread corruption and poverty and complained that

Mobutu Sese Seko's "military regime... is extremely galling to a black from South Africa." In Nigeria, he expressed concern at

Igbo resentment following the crushing of their

Republic of Biafra. In 1972 he travelled around East Africa, where he was impressed by

Jomo Kenyatta's Kenyan government and witnessed

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 30 May 192816 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 until Uganda–Tanzania War, his overthrow in 1979. He ruled as a Military dictatorship, ...

's

expulsion of Ugandan Asians.

During the early 1970s, Tutu's theology changed due to his experiences in Africa and his discovery of

liberation theology. He was also attracted to

black theology, attending a 1973 conference on the subject at New York City's

Union Theological Seminary. There, he presented a paper in which he stated that "black theology is an engaged not an academic, detached theology. It is a gut level theology, relating to the real concerns, the life and death issues of the black man." He stated that his paper was not an attempt to demonstrate the academic respectability of black theology but rather to make "a straightforward, perhaps shrill, statement about an existent. Black theology is. No permission is being requested for it to come into being... Frankly the time has passed when we will wait for the white man to give us permission to do our thing. Whether or not he accepts the intellectual respectability of our activity is largely irrelevant. We will proceed regardless." Seeking to fuse the African-American derived black theology with

African theology, Tutu's approach contrasted with that of those African theologians, like

John Mbiti, who regarded black theology as a foreign import irrelevant to Africa.

Dean of St Mary's Cathedral, Johannesburg and Bishop of Lesotho: 1975–1978

In 1975, Tutu was nominated to be the new

Bishop of Johannesburg, although he lost out to

Timothy Bavin. Bavin suggested that Tutu take his newly vacated position, that of the

dean of St Mary's Cathedral, Johannesburg. Tutu was elected to this position—the fourth highest in South Africa's Anglican hierarchy—in March 1975, becoming the first black man to do so, an appointment making headline news in South Africa. Tutu was officially installed as dean in August 1975. The cathedral was packed for the event. Moving to the city, Tutu lived not in the official dean's residence in the white suburb of

Houghton but rather in

a house on a middle-class street in the

Orlando West township of

Soweto, a largely impoverished black area. Although majority white, the cathedral's congregation was racially mixed, something that gave Tutu hope that a racially equal, de-segregated future was possible for South Africa. He encountered some resistance to his attempts to modernise the

liturgies

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a community, communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, ...

used by the congregation, including his attempts to replace masculine pronouns with gender neutral ones.

Tutu used his position to speak out on social issues, publicly endorsing an international

economic boycott of South Africa over apartheid. He met with Black Consciousness and Soweto leaders, and shared a platform with anti-apartheid campaigner

Winnie Mandela in opposing the government's

Terrorism Act, 1967. He held a 24-hour vigil for racial harmony at the cathedral where he prayed for activists detained under the act. In May 1976, he wrote to Prime Minister

B. J. Vorster, warning that if the government maintained apartheid then the country would erupt in racial violence. Six weeks later, the

Soweto uprising broke out as black youth clashed with police. Over the course of ten months, at least 660 were killed, most under the age of 24. Tutu was upset by what he regarded as the lack of outrage from

white South Africans; he raised the issue in his Sunday sermon, stating that the white silence was "deafening" and asking if they would have shown the same nonchalance had white youths been killed.

After seven months as dean, Tutu was nominated to become the

Bishop of Lesotho. Although Tutu did not want the position, he was elected to it in March 1976 and reluctantly accepted. This decision upset some of his congregation, who felt that he had used their parish as a stepping stone to advance his career. In July,

Bill Burnett consecrated Tutu as a bishop at St Mary's Cathedral. In August, Tutu was enthroned as the Bishop of Lesotho in a ceremony at

Maseru's Cathedral of St Mary and St James; thousands attended, including King

Moshoeshoe II and Prime Minister

Leabua Jonathan. Travelling through the largely rural diocese, Tutu learned

Sesotho. He appointed Philip Mokuku as the first dean of the diocese and placed great emphasis on

further education for the Basotho clergy. He befriended the royal family although his relationship with Jonathan's government was strained. In September 1977 he returned to South Africa to speak at the

Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

funeral of Black Consciousness activist

Steve Biko, who had been killed by police. At the funeral, Tutu stated that Black Consciousness was "a movement by which God, through Steve, sought to awaken in the black person a sense of his intrinsic value and worth as a child of God".

General-Secretary of the South African Council of Churches: 1978–1985

SACC leadership

After John Rees stepped down as general secretary of the

South African Council of Churches, Tutu was among the nominees for his successor. John Thorne was ultimately elected to the position, although stepped down after three months, with Tutu's agreeing to take over at the urging of the

synod of bishops. His decision angered many Anglicans in Lesotho, who felt that Tutu was abandoning them. Tutu took charge of the SACC in March 1978. Back in Johannesburg—where the SACC's headquarters were based at Khotso House—the Tutus returned to their former Orlando West home, now bought for them by an anonymous foreign donor. Leah gained employment as the assistant director of the

Institute of Race Relations.

The SACC was one of the few Christian institutions in South Africa where black people had the majority representation; Tutu was its first black leader. There, he introduced a schedule of daily staff prayers, regular Bible study, monthly Eucharist, and silent retreats. Hegr also developed a new style of leadership, appointing senior staff who were capable of taking the initiative, delegating much of the SACC's detailed work to them, and keeping in touch with them through meetings and memorandums. Many of his staff referred to him as "Baba" (father). He was determined that the SACC become one of South Africa's most visible human rights advocacy organisations. His efforts gained him international recognition; the closing years of the 1970s saw him elected a

fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of KCL and receive honorary doctorates from the

University of Kent

The University of Kent (formerly the University of Kent at Canterbury, abbreviated as UKC) is a Collegiate university, collegiate public university, public research university based in Kent, United Kingdom. The university was granted its roya ...

, General Theological Seminary, and

Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

.

As head of the SACC, Tutu's time was dominated by fundraising for the organisation's projects. Under Tutu's tenure, it was revealed that one of the SACC's divisional directors had been stealing funds. In 1981 a government commission launched to investigate the issue, headed by the judge

C. F. Eloff. Tutu gave evidence to the commission, during which he condemned apartheid as "evil" and "unchristian". When the Eloff report was published, Tutu criticised it, focusing particularly on the absence of any theologians on its board, likening it to "a group of blind men" judging the

Chelsea Flower Show. In 1981 Tutu also became the rector of St Augustine's Church in Soweto's

Orlando West. The following year he published a collection of his sermons and speeches, ''Crying in the Wilderness: The Struggle for Justice in South Africa''; another volume, ''Hope and Suffering'', appeared in 1984.

Activism and the Nobel Peace Prize

Tutu testified on behalf of a captured

cell of

Umkhonto we Sizwe, an armed anti-apartheid group linked to the banned

African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC). He stated that although he was committed to non-violence and censured all who used violence, he could understand why black Africans became violent when their non-violent tactics had failed to overturn apartheid. In an earlier address, he had opined that an armed struggle against South Africa's government had little chance of succeeding but also accused Western nations of hypocrisy for condemning armed liberation groups in southern Africa while they had praised similar organisations in Europe during the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Tutu also signed a petition calling for the release of ANC activist Nelson Mandela, leading to a correspondence between the pair.

After Tutu told journalists that he supported an international economic boycott of South Africa, he was reprimanded before government ministers in October 1979. In March 1980, the government confiscated his passport; this raised his international profile. In 1980, the SACC committed itself to supporting

civil disobedience against apartheid. After Thorne was arrested in May, Tutu and Joe Wing led a protest march during which they were arrested, imprisoned overnight, and fined. In the aftermath, a meeting was organised between 20 church leaders including Tutu, Prime Minister

P. W. Botha, and seven government ministers. At this August meeting the clerical leaders unsuccessfully urged the government to end apartheid. Although some clergy saw this dialogue as pointless, Tutu disagreed, commenting: "

Moses went to Pharaoh repeatedly to secure the release of the Israelites."

In January 1981, the government returned Tutu's passport. In March, he embarked on a five-week tour of Europe and North America, meeting politicians including the

UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, and addressing the

UN Special Committee Against Apartheid. In England, he met

Robert Runcie and gave a sermon in

Westminster Abbey, while in

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

he met Pope

John Paul II. On his return to South Africa, Botha again ordered Tutu's passport confiscated, preventing him from personally collecting several further honorary degrees. It was returned 17 months later. In September 1982 Tutu addressed the Triennial Convention of the

Episcopal Church in

New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

before traveling to Kentucky to see his daughter Naomi, who lived there with her American husband. Tutu gained a popular following in the US, where he was often compared to civil rights leader

Martin Luther King Jr., although white

conservatives like

Pat Buchanan and

Jerry Falwell

Jerry Laymon Falwell Sr. (August 11, 1933 – May 15, 2007) was an American Baptist pastor, televangelist, and conservatism in the United States, conservative activist. He was the founding pastor of the Thomas Road Baptist Church, a megachurch ...

lambasted him as an alleged communist sympathiser.

By the 1980s, Tutu was an icon for many black South Africans, a status rivalled only by Mandela. In August 1983, he became a patron of the new anti-apartheid

United Democratic Front (UDF). Tutu angered much of South Africa's press and white minority, especially apartheid supporters. Pro-government media like ''

The Citizen'' and the

South African Broadcasting Corporation criticised him, often focusing on how his middle-class lifestyle contrasted with the poverty of the blacks he claimed to represent. He received

hate mail and death threats from white far-right groups like the

Wit Wolwe. Although he remained close with prominent white liberals like

Helen Suzman, his angry anti-government rhetoric also alienated many white liberals like

Alan Paton and

Bill Burnett, who believed that apartheid could be gradually reformed away.

In 1984, Tutu embarked on a three-month sabbatical at the

General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York. In the city, he was invited to address the

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

, later meeting the

Congressional Black Caucus and the subcommittees on Africa in the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

and the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. He was also invited to the

White House, where he unsuccessfully urged President

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

to change his approach to South Africa. He was troubled that Reagan had a warmer relationship with South Africa's government than his predecessor

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

, describing Reagan's government as "an unmitigated disaster for us blacks". Tutu later called Reagan "a racist pure and simple".

In New York City, Tutu was informed that he had won the 1984

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

; he had previously been nominated in 1981, 1982, and 1983. The Nobel Prize selection committee had wanted to recognise a South African and thought Tutu would be a less controversial choice than Mandela or

Mangosuthu Buthelezi. In December, he attended the award ceremony in

Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

—which was hampered by a bomb scare—before returning home via Sweden, Denmark, Canada, Tanzania, and Zambia. He shared the US$192,000 prize money with his family, SACC staff, and a scholarship fund for South Africans in exile. He was the second South African to receive the award, after

Albert Luthuli in 1960. South Africa's government and mainstream media either downplayed or criticised the award, while the

Organisation of African Unity hailed it as evidence of apartheid's impending demise.

Bishop of Johannesburg: 1985–1986

After Timothy Bavin retired as Bishop of Johannesburg, Tutu was among five replacement candidates. An elective assembly met at

St Barnabas' College in October 1984 and although Tutu was one of the two most popular candidates, the white laity voting bloc consistently voted against his candidature. To break deadlock, a bishops' synod met and decided to appoint Tutu. Black Anglicans celebrated, although many white Anglicans were angry; some withdrew their diocesan quota in protest. Tutu was enthroned as the sixth Bishop of Johannesburg in St Mary's Cathedral in February 1985. The first black man to hold the role, he took over the country's largest diocese, comprising 102 parishes and 300,000 parishioners, approximately 80% of whom were black. In his inaugural sermon, Tutu called on the international community to introduce economic sanctions against South Africa unless apartheid was not being dismantled within 18 to 24 months. He sought to reassure white South Africans that he was not the "horrid ogre" some feared; as bishop he spent much time wooing the support of white Anglicans in his diocese, and resigned as patron of the UDF.

The mid-1980s saw growing clashes between black youths and the security services; Tutu was invited to speak at many of the funerals of those youths killed. At a

Duduza funeral, he intervened to stop the crowd from killing a black man accused of being a government informant. Tutu angered some black South Africans by speaking against the torture and killing of suspected collaborators. For these militants, Tutu's calls for non-violence were perceived as an obstacle to revolution. When Tutu accompanied the US politician

Ted Kennedy on the latter's visit to South Africa in January 1985, he was angered that protesters from the

Azanian People's Organisation (AZAPO)—who regarded Kennedy as an agent of capitalism and

American imperialism—disrupted proceedings.

Amid the violence, the ANC called on supporters to make South Africa "

ungovernable"; foreign companies increasingly disinvested in the country and the

South African rand

The South African rand, or simply the rand, (currency sign, sign: R; ISO 4217, code: ZAR) is the official currency of South Africa. It is subdivided into 100 Cent (currency), cents (sign: "c"), and a comma separates the rand and cents.

The Sou ...

reached a record low. In July 1985, Botha declared a state of emergency in 36 magisterial districts, suspending civil liberties and giving the security services additional powers; he rebuffed Tutu's offer to serve as a go-between for the government and leading black organisations. Tutu continued protesting; in April 1985, he led a small march of clergy through Johannesburg to protest the arrest of Geoff Moselane. In October 1985, he backed the National Initiative for Reconciliation's proposal for people to refrain from work for a day of prayer, fasting, and mourning. He also proposed a

national strike against apartheid, angering trade unions whom he had not consulted beforehand.

Tutu continued promoting his cause abroad. In May 1985 he embarked on a speaking tour of the United States, and in October 1985 addressed the political committee of the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

, urging the international community to impose sanctions on South Africa if apartheid was not dismantled within six months. Proceeding to the United Kingdom, he met with Prime Minister

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

. He also formed a Bishop Tutu Scholarship Fund to financially assist South African students living in exile. He returned to the US in May 1986, and in August 1986 visited Japan, China, and Jamaica to promote sanctions. Given that most senior anti-apartheid activists were imprisoned, Mandela referred to Tutu as "public enemy number one for the powers that be".

Archbishop of Cape Town: 1986–1994

After

Philip Russell announced his retirement as the

Archbishop of Cape Town, in February 1986 the Black Solidarity Group formed a plan to get Tutu appointed as his replacement. At the time of the meeting, Tutu was in

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

, Georgia, receiving the

Martin Luther King, Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize. Tutu secured a two-thirds majority from both the clergy and laity and was then ratified in a unanimous vote by the synod of bishops. He was the first black man to hold the post. Some white Anglicans left the church in protest. Over 1,300 people attended his enthronement ceremony at the

Cathedral of St George the Martyr on 7 September 1986.

After the ceremony, Tutu held an open-air Eucharist for 10,000 people at the Cape Showgrounds in

Goodwood, where he invited

Albertina Sisulu and

Allan Boesak to give political speeches.

Tutu moved into the archbishop's

Bishopscourt residence; this was illegal as he did not have official permission to reside in what the state allocated as a "white area". He obtained money from the church to oversee renovations of the house, and had a children's playground installed in its grounds, opening this and the Bishopscourt swimming pool to members of his diocese. He invited the English priest Francis Cull to set up the Institute of Christian Spirituality at Bishopscourt, with the latter moving into a building in the house's grounds. Such projects led to Tutu's ministry taking up an increasingly large portion of the Anglican church's budget, which Tutu sought to expand through requesting donations from overseas. Some Anglicans were critical of his spending.

Tutu's vast workload was managed with the assistance of his executive officer

Njongonkulu Ndungane and

Michael Nuttall, who in 1989 was elected dean of the province. In church meetings, Tutu drew upon traditional African custom by adopting a consensus-building model of leadership, seeking to ensure that competing groups in the church reached a compromise and thus all votes would be unanimous rather than divided. He secured approval for the ordination of female priests in the Anglican church, having likened the exclusion of women from the position to apartheid. He appointed gay priests to senior positions and privately criticised the church's insistence that gay priests remain celibate.

Along with Boesak and

Stephen Naidoo, Tutu mediated conflicts between black protesters and the security forces; they for instance worked to avoid clashes at the 1987 funeral of ANC guerrilla

Ashley Kriel. In February 1988, the government banned 17 black or multi-racial organisations, including the UDF, and restricted the activities of trade unions. Church leaders organised a protest march, and after that too was banned they established the Committee for the Defense of Democracy. When the group's rally was banned, Tutu, Boesak, and Naidoo organised a service at St George's Cathedral to replace it.

Opposed on principle to

capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, in March 1988 Tutu took up the cause of the

Sharpeville Six who had been sentenced to death. He telephoned representatives of the American, British, and German governments urging them to pressure Botha on the issue, and personally met with Botha at the latter's

Tuynhuys home to discuss the issue. The two did not get on well, and argued. Botha accused Tutu of supporting the ANC's armed campaign; Tutu said that while he did not support their use of violence, he supported the ANC's objective of a non-racial, democratic South Africa. The death sentences were ultimately commuted.

In May 1988, the government launched a covert campaign against Tutu, organised in part by the

Stratkom wing of the

State Security Council. The security police printed leaflets and stickers with anti-Tutu slogans while unemployed blacks were paid to protest when he arrived at the airport. Traffic police briefly imprisoned Leah when she was late to renew her motor vehicle license. Although the security police organised assassination attempts on various anti-apartheid Christian leaders, they later claimed to have never done so for Tutu, deeming him too high-profile.

Tutu remained actively involved in acts of

civil disobedience against the government; he was encouraged by the fact that many whites also took part in these protests. In August 1989 he helped to organise an "Ecumenical Defiance Service" at St George's Cathedral, and shortly after joined protests at segregated beaches outside Cape Town. To mark the sixth anniversary of the UDF's foundation he held a "service of witness" at the cathedral, and in September organised a church memorial for those protesters who had been killed in clashes with the security forces. He organised a

protest march through Cape Town for later that month, which the new President

F. W. de Klerk agreed to permit; a multi-racial crowd containing an estimated 30,000 people took part. That the march had been permitted inspired similar demonstrations to take place across the country. In October, de Klerk met with Tutu, Boesak, and

Frank Chikane; Tutu was impressed that "we were listened to". In 1994, a further collection of Tutu's writings, ''The Rainbow People of God'', was published, and followed the next year with his ''An African Prayer Book'', a collection of prayers from across the continent accompanied by the Archbishop's commentary.

Dismantling of apartheid

In February 1990, de Klerk lifted the ban on political parties like the ANC; Tutu telephoned him to praise the move. De Klerk then announced Nelson Mandela's release from prison; at the ANC's request, Mandela and his wife Winnie stayed at Bishopscourt on the former's first night of freedom. Tutu and Mandela met for the first time in 35 years at

Cape Town City Hall, where Mandela spoke to the assembled crowds. Tutu invited Mandela to attend an Anglican synod of bishops in February 1990, at which the latter described Tutu as the "people's archbishop". There, Tutu and the bishops called for an end to foreign sanctions once the transition to

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

was "irreversible", urged anti-apartheid groups to end armed struggle, and banned Anglican clergy from belonging to political parties. Many clergy were angry that the latter was being imposed without consultation, although Tutu defended it, stating that priests affiliating with political parties would prove divisive, particularly amid growing inter-party violence.

In March, violence broke out between supporters of the ANC and of

Inkatha in

kwaZulu; Tutu joined the SACC delegation in talks with Mandela, de Klerk, and Inkatha leader

Mangosuthu Buthelezi in

Ulundi. Church leaders urged Mandela and Buthelezi to hold a joint rally to quell the violence. Although Tutu's relationship with Buthelezi had always been strained, particularly due to Tutu's opposition to Buthelezi's collaboration in the government's

Bantustan system, Tutu repeatedly visited Buthelezi to encourage his involvement in the democratic process. As the ANC-Inkatha violence spread from

kwaZulu into the

Transvaal, Tutu toured affected townships in

Witwatersrand, later meeting with victims of the

Sebokeng and

Boipatong massacres.

Like many activists, Tutu believed a "

third force" was stoking tensions between the ANC and Inkatha; it later emerged that intelligence agencies were supplying Inkatha with weapons to weaken the ANC's negotiating position. Unlike some ANC figures, Tutu never accused de Klerk of personal complicity in this. In November 1990, Tutu organised a "summit" at Bishopscourt attended by both church and black political leaders in which he encouraged the latter to call on their supporters to avoid violence and allow free political campaigning. After the

South African Communist Party leader

Chris Hani was assassinated, Tutu spoke at Hani's funeral outside Soweto. Experiencing physical exhaustion and ill-health, Tutu then undertook a four-month sabbatical at

Emory University

Emory University is a private university, private research university in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It was founded in 1836 as Emory College by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory. Its main campu ...

's Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Georgia.

Tutu was exhilarated by the prospect of South Africa transforming towards universal suffrage via a negotiated transition rather than civil war. He allowed his face to be used on posters encouraging people to vote. When the

April 1994 multi-racial general election took place, Tutu was visibly exuberant, telling reporters that "we are on cloud nine". He voted in Cape Town's

Gugulethu township. The ANC won the election and Mandela was declared president, heading a government of national unity. Tutu attended Mandela's inauguration ceremony; he had planned its religious component, insisting that Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and Hindu leaders all take part.

International affairs

Tutu also turned his attention to foreign events. In 1987, he gave the keynote speech at the

All Africa Conference of Churches (AACC) in

Lomé, Togo, calling on churches to champion the oppressed throughout Africa; he stated that "it pains us to have to admit that there is less freedom and personal liberty in most of Africa now then there was during the much-maligned colonial days." Elected president of the AACC, he worked closely with general-secretary José Belo over the next decade. In 1989 they visited Zaire to encourage the country's churches to distance themselves from Seko's government. In 1994, he and Belo visited war-torn Liberia; they met

Charles Taylor, but Tutu did not trust his promise of a ceasefire. In 1995, Mandela sent Tutu to Nigeria to meet with military leader

Sani Abacha to request the release of imprisoned politicians

Moshood Abiola and

Olusegun Obasanjo. In July 1995, he visited Rwanda a year after the

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

, preaching to 10,000 people in

Kigali, calling for justice to be tempered with mercy towards the

Hutus who had orchestrated the genocide. Tutu also travelled to other parts of world, for instance spending March 1989 in Panama and Nicaragua.

Tutu spoke about the

Israeli–Palestinian conflict, arguing that Israel's treatment of

Palestinians

Palestinians () are an Arab ethnonational group native to the Levantine region of Palestine.

*: "Palestine was part of the first wave of conquest following Muhammad's death in 632 CE; Jerusalem fell to the Caliph Umar in 638. The indigenou ...

was reminiscent of South African apartheid. He also criticised Israel's arms sales to South Africa, wondering how the Jewish state could co-operate with a government containing Nazi sympathisers.

At the same time, Tutu recognised Israel's right to exist. In 1989, he visited

Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ) is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist coalition that is internationally recognized as the official representative of the Palestinians, Palestinian people in both the occupied Pale ...

leader

Yasser Arafat

Yasser Arafat (4 or 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, Presid ...

in Cairo, urging him to accept Israel's existence. In the same year, during a speech in New York City, Tutu observed Israel had a "right to territorial integrity and fundamental security", but criticised Israel's complicity in the

Sabra and Shatila massacre and condemned Israel's support for the apartheid regime in South Africa. Tutu called for a

Palestinian state

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, collectively known as th ...

, and emphasised that his criticisms were of the Israeli government rather than of Jews. At the invitation of Palestinian bishop

Samir Kafity, he undertook a Christmas pilgrimage to

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, where he gave a sermon near

Bethlehem, in which he called for a

two-state solution. On his 1989 trip, he laid a wreath at the

Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial and gave a sermon on the importance of forgiving the perpetrators of

the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

;

the sermon drew criticism from Jewish groups around the world. Jewish anger was exacerbated by Tutu's attempts to evade accusations of

antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

through comments such as "my dentist is a Dr. Cohen".

Alan Dershowitz and

David Bernstein called Tutu antisemitic for his comments about "the

Jewish lobby", calling Jews a “peculiar people,” and accusing "'the Jews' of causing many of the world’s problems".

Tutu also spoke out regarding

the Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

in Northern Ireland. At the

Lambeth Conference

The Lambeth Conference convenes as the Archbishop of Canterbury summons an assembly of Anglican bishops every ten years. The first took place at Lambeth in 1867.

As regional and national churches freely associate with the Anglican Communion, ...

of 1988, he backed a resolution condemning the use of violence by all sides; Tutu believed that

Irish republicans had not exhausted peaceful means of bringing about change and should not resort to armed struggle. Three years later, he gave a televised service from

Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

's

Christ Church Cathedral, calling for negotiations between all factions. He visited

Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

in 1998 and again in 2001.

Later life

In October 1994, Tutu announced his intention of retiring as archbishop in 1996. Although retired archbishops normally return to the position of bishop, the other bishops gave him a new title: "archbishop emeritus". A farewell ceremony was held at St George's Cathedral in June 1996, attended by senior politicians like Mandela and de Klerk. There, Mandela awarded Tutu the

Order for Meritorious Service, South Africa's highest honour. Tutu was succeeded as archbishop by

Njongonkulu Ndungane.

In January 1997, Tutu was diagnosed with

prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the neoplasm, uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Abnormal growth of the prostate tissue is usually detected through Screening (medicine), screening tests, ...

and travelled abroad for treatment. He publicly revealed his diagnosis, hoping to encourage other men to go for prostate exams. He faced recurrences of the disease in 1999 and 2006. Back in South Africa, he divided his time between homes in Soweto's Orlando West and Cape Town's

Milnerton area. In 2000, he opened an office in Cape Town. In June 2000, the Cape Town-based Desmond Tutu Peace Centre was launched, which in 2003 launched an Emerging Leadership Program.

Conscious that his presence in South Africa might overshadow Ndungane, Tutu agreed to a two-year

visiting professorship at

Emory University

Emory University is a private university, private research university in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It was founded in 1836 as Emory College by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory. Its main campu ...

in Atlanta, Georgia. This took place between 1998 and 2000, and during the period he wrote a book about the TRC, ''No Future Without Forgiveness''. In early 2002 he taught at the Episcopal Divinity School in

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 United States census, ...

. From January to May 2003 he taught at the

University of North Carolina

The University of North Carolina is the Public university, public university system for the state of North Carolina. Overseeing the state's 16 public universities and the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, it is commonly referre ...

. In January 2004, he was visiting professor of postconflict societies at King's College London, his ''alma mater''. While in the United States, he signed up with a speakers' agency and travelled widely on speaking engagements; this gave him financial independence in a way that his clerical pension would not. In his speeches, he focused on South Africa's transition from apartheid to universal suffrage, presenting it as a model for other troubled nations to adopt. In the United States, he thanked anti-apartheid activists for campaigning for sanctions, also calling for United States companies to now invest in South Africa.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission: 1996–1998

Tutu popularised the term "

Rainbow Nation" as a metaphor for

post-apartheid South Africa after 1994 under ANC rule. He had first used the metaphor in 1989 when he described a multi-racial protest crowd as the "rainbow people of God". Tutu advocated what liberation theologians call "critical solidarity", offering support for pro-democracy forces while reserving the right to criticise his allies. He criticised Mandela on several points, such as his tendency to wear brightly coloured

Madiba shirts, which he regarded as inappropriate; Mandela offered the tongue-in-cheek response that it was ironic coming from a man who wore dresses. More serious was Tutu's criticism of Mandela's retention of South Africa's apartheid-era armaments industry and the significant pay packet that newly elected members of parliament adopted. Mandela hit back, calling Tutu a "populist" and stating that he should have raised these issues privately rather than publicly.

A key question facing the post-apartheid government was how they would respond to the various human rights abuses that had been committed over the previous decades by both the state and by anti-apartheid activists. The National Party had wanted a comprehensive amnesty package whereas the ANC wanted trials of former state figures.

Alex Boraine helped Mandela's government to draw up legislation for the establishment of a

Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which was passed by parliament in July 1995. Nuttall suggested that Tutu become one of the TRC's seventeen commissioners, while in September a synod of bishops formally nominated him. Tutu proposed that the TRC adopt a threefold approach: the first being confession, with those responsible for human rights abuses fully disclosing their activities, the second being forgiveness in the form of a legal amnesty from prosecution, and the third being restitution, with the perpetrators making amends to their victims.

Mandela named Tutu as the chair of the TRC, with Boraine as his deputy. The commission was a significant undertaking, employing over 300 staff, divided into three committees, and holding as many as four hearings simultaneously. In the TRC, Tutu advocated "restorative justice", something which he considered characteristic of traditional African jurisprudence "in the spirit of ''ubuntu''". As head of the commission, Tutu had to deal with its various inter-personal problems, with much suspicion between those on its board who had been anti-apartheid activists and those who had supported the apartheid system. He acknowledged that "we really were like a bunch of prima donnas, frequently hypersensitive, often taking umbrage easily at real or imagined slights." Tutu opened meetings with prayers and often referred to Christian teachings when discussing the TRC's work, frustrating some who saw him as incorporating too many religious elements into an expressly secular body.

The first hearing took place in April 1996. The hearings were publicly televised and had a considerable impact on South African society. He had very little control over the committee responsible for granting amnesty, instead chairing the committee which heard accounts of human rights abuses perpetrated by both anti-apartheid and apartheid figures. While listening to the testimony of victims, Tutu was sometimes overwhelmed by emotion and cried during the hearings. He singled out those victims who expressed forgiveness towards those who had harmed them and used these individuals as his leitmotif. The ANC's image was tarnished by the revelations that some of its activists had engaged in torture, attacks on civilians, and other human rights abuses. It sought to suppress part of the final TRC report, infuriating Tutu. He warned of the ANC's "abuse of power", stating that "yesterday's oppressed can quite easily become today's oppressors... We've seen it happen all over the world and we shouldn't be surprised if it happens here." Tutu presented the five-volume TRC report to Mandela in a public ceremony in

Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

in October 1998. Ultimately, Tutu was pleased with the TRC's achievement, believing that it would aid long-term reconciliation, although he recognised its short-comings.

Social and international issues: 1999–2009

Post-apartheid, Tutu's status as a

gay rights activist kept him in the public eye more than any other

issue facing the Anglican Church; his views on the issue became well known through his speeches and sermons. Tutu equated discrimination against homosexuals with discrimination against black people and women. After the 1998 Lambeth Conference of bishops reaffirmed the church's opposition to same-sex sexual acts, Tutu stated that he was "ashamed to be an Anglican." He thought Archbishop of Canterbury

Rowan Williams was too accommodating towards Anglican conservatives who wanted to eject North American Anglican churches from the

Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is a Christian Full communion, communion consisting of the Church of England and other autocephalous national and regional churches in full communion. The archbishop of Canterbury in England acts as a focus of unity, ...

after they expressed a pro-gay rights stance. In 2007, Tutu accused the church of being obsessed with homosexuality, declaring: "If God, as they say, is homophobic, I wouldn't worship that God."

Tutu also spoke out on the need to combat the

HIV/AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

pandemic, in June 2003 stating that "Apartheid tried to destroy our people and apartheid failed. If we don't act against HIV-AIDS, it may succeed, for it is already decimating our population." On the April 2005 election of

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

—who was known for his conservative views on issues of gender and sexuality—Tutu described it as unfortunate that the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

was now unlikely to change either its opposition to the use of

condoms "amidst the fight against HIV/AIDS" or its opposition to the ordination of women priests. To help combat child trafficking, in 2006 Tutu launched a global campaign, organised by the aid organisation

Plan

A plan is typically any diagram or list of steps with details of timing and resources, used to achieve an Goal, objective to do something. It is commonly understood as a modal logic, temporal set (mathematics), set of intended actions through wh ...

, to ensure that all children are registered at birth.

Tutu retained his interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and after the signing of the

Oslo Accords was invited to

Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( or , ; ), sometimes rendered as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and usually referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a popula ...

to attend the

Peres Center for Peace. He became increasingly frustrated following the collapse of the

2000 Camp David Summit, and in 2002 gave a widely publicised speech denouncing Israeli policy regarding the Palestinians and calling for sanctions against Israel. Comparing the Israeli-Palestinian situation with that in South Africa, he said that "one reason we succeeded in South Africa that is missing in the Middle East is quality of leadership – leaders willing to make unpopular compromises, to go against their own constituencies, because they have the wisdom to see that would ultimately make peace possible." Tutu was named to head a United Nations fact-finding mission to

Beit Hanoun in the Gaza Strip to investigate the

November 2006 incident in which soldiers from the

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branches: the Israeli Ground Forces, the Israeli Air Force, and ...

killed 19 civilians. Israeli officials expressed concern that the report would be biased against Israel. Tutu cancelled the trip in mid-December, saying that Israel had refused to grant him the necessary travel clearance after more than a week of discussions.

In 2003, Tutu was the scholar in residence at the

University of North Florida. It was there, in February, that he broke his normal rule on not joining protests outside South Africa by taking part in a New York City demonstration against plans for the United States to launch the

Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

. He telephoned

Condoleezza Rice urging the United States government not to go to war without a resolution from the

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

. Tutu questioned why Iraq was being singled out for allegedly possessing

weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a Biological agent, biological, chemical weapon, chemical, Radiological weapon, radiological, nuclear weapon, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill or significantly harm many people or cause great dam ...

when Europe, India, and Pakistan also had many such devices. In 2004, he appeared in ''

Honor Bound to Defend Freedom'', an

Off Broadway play in New York City critical of the American detention of prisoners at

Guantánamo Bay. In January 2005, he added his voice to the growing dissent over terrorist suspects held at Guantánamo's

Camp X-Ray, stating that these detentions without trial were "utterly unacceptable" and comparable to the apartheid-era detentions. He also criticised the UK's introduction of measures to detain terrorist subjects for 28 days without trial.

In 2012, he called for US President

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

and British Prime Minister

Tony Blair to be tried by the

International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an intergovernmental organization and International court, international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute ...

for initiating the Iraq War.

In 2004, he gave the inaugural lecture at the Church of Christ the King, where he commended the achievements made in South Africa over the previous decade although warned of widening wealth disparity among its population. He questioned the government's spending on armaments, its policy regarding

Robert Mugabe's government in Zimbabwe, and the manner in which

Nguni-speakers dominated senior positions, stating that this latter issue would stoke ethnic tensions. He made the same points three months later when giving the annual Nelson Mandela Lecture in Johannesburg. There, he charged the ANC under

Thabo Mbeki

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki (; born 18 June 1942) is a South African politician who served as the 2nd democratic president of South Africa from 14 June 1999 to 24 September 2008, when he resigned at the request of his party, the African National Cong ...