Death Cap on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Amanita phalloides'' ( ), commonly known as the death cap, is a deadly poisonous

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped)

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped)

The fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal

The fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal

UK Telegraph Newspaper (September 2008) - One woman dead, another critically ill after eating Death Cap fungi

* [http://www.mushroomexpert.com/amanita_phalloides.html ''Amanita phalloides'': the death cap]

''Amanita phalloides'': Invasion of the Death Cap

* [http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Amanita_phalloides.html California Fungi—Amanita phalloides]

Death cap in Australia - ANBG website

On the Trail of the Death Cap Mushroom

from National Public Radio * {{Authority control Amanita, phalloides Fungi of Africa Fungi of Europe Deadly fungi Hepatotoxins Fungi described in 1821 Fungus species

basidiomycete

Basidiomycota () is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Basid ...

fungus

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

and mushroom

A mushroom or toadstool is the fleshy, spore-bearing Sporocarp (fungi), fruiting body of a fungus, typically produced above ground on soil or another food source. ''Toadstool'' generally refers to a poisonous mushroom.

The standard for the n ...

, one of many in the genus ''Amanita

The genus ''Amanita'' contains about 600 species of agarics, including some of the most toxic known mushrooms found worldwide, as well as some well-regarded Edible mushroom, edible species (and many species of unknown edibility). The genus is re ...

''. Originating in Europe but later introduced to other parts of the world since the late twentieth century, ''A. phalloides'' forms ectomycorrhiza

An ectomycorrhiza (from Greek ἐκτός ', "outside", μύκης ', "fungus", and ῥίζα ', "root"; ectomycorrhizas or ectomycorrhizae, abbreviated EcM) is a form of symbiotic relationship that occurs between a fungal symbiont, or mycobio ...

s with various broadleaved trees. In some cases, the death cap has been introduced to new regions with the cultivation of non-native species of oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

, chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

Description

...

, and pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

. The large fruiting bodies (mushroom

A mushroom or toadstool is the fleshy, spore-bearing Sporocarp (fungi), fruiting body of a fungus, typically produced above ground on soil or another food source. ''Toadstool'' generally refers to a poisonous mushroom.

The standard for the n ...

s) appear in summer and autumn; the caps

Caps are flat headgear.

Caps or CAPS may also refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* CESG Assisted Products Service, provided by the U.K. Government Communications Headquarters

* Composite Application Platform Suite, by Java Caps, a Java ...

are generally greenish in colour with a white stipe and gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

s. The cap colour is variable, including white forms, and is thus not a reliable identifier.

These toxic mushrooms resemble several edible species (most notably Caesar's mushroom and the straw mushroom) commonly consumed by humans, increasing the risk of accidental poisoning

Poisoning is the harmful effect which occurs when Toxicity, toxic substances are introduced into the body. The term "poisoning" is a derivative of poison, a term describing any chemical substance that may harm or kill a living organism upon ...

. Amatoxin

Amatoxins are a subgroup of at least nine related cyclic peptide toxins found in three genera of deadly poisonous mushrooms (''Amanita'', '' Galerina'' and '' Lepiota'') and one species of the genus '' Pholiotina''. Amatoxins are very potent, as li ...

s, the class of toxins found in these mushrooms, are thermostable: they resist changes due to heat, so their toxic effects are not reduced by cooking.

''Amanita phalloides'' is the most poisonous of all known mushrooms. It is estimated that as little as half a mushroom contains enough toxin to kill an adult human. It is also the deadliest mushroom worldwide, responsible for 90% of mushroom-related fatalities every year. It has been involved in the majority of human deaths from mushroom poisoning,Benjamin, p.200. possibly including Roman Emperor Claudius in AD 54 and Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in 1740. It has also been the subject of much research and many of its biologically active agents have been isolated. The principal toxic constituent is α-Amanitin, which causes liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

and kidney failure

Kidney failure, also known as renal failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney fa ...

.

Taxonomy

The death cap is named inLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

as such in the correspondence between the English physician Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne ( "brown"; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a d ...

and Christopher Merrett. Also, it was described by French botanist Sébastien Vaillant

Sébastien Vaillant (; May 26, 1669 – May 20, 1722) was a French botanist who was born at Vigny, Val-d'Oise, Vigny in present-day Val d'Oise.

Early years

Vaillant went to school at the age of four and by the age of five, he was collecting p ...

in 1727, who gave a succinct phrase name "''Fungus phalloides, annulatus, sordide virescens, et patulus''"—a recognizable name for the fungus today. Though the scientific name

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin gramm ...

''phalloides'' means "phallus-shaped", it is unclear whether it is named for its resemblance to a literal phallus

A phallus (: phalli or phalluses) is a penis (especially when erect), an object that resembles a penis, or a mimetic image of an erect penis. In art history, a figure with an erect penis is described as ''ithyphallic''.

Any object that symbo ...

or the stinkhorn mushrooms ''Phallus

A phallus (: phalli or phalluses) is a penis (especially when erect), an object that resembles a penis, or a mimetic image of an erect penis. In art history, a figure with an erect penis is described as ''ithyphallic''.

Any object that symbo ...

''.

In 1821, Elias Magnus Fries

Elias Magnus Fries (15 August 1794 – 8 February 1878) was a Swedish mycologist and botanist. He is sometimes called the Mycology, "Linnaeus of Mycology". In his works he described and assigned botanical names to hundreds of fungus and li ...

described it as ''Agaricus phalloides'', but included all white amanitas within its description. Finally, in 1833, Johann Heinrich Friedrich Link

Johann Heinrich Friedrich Link (2 February 1767 – 1 January 1851) was a German natural history, naturalist and botanist.

Biography

Link was born at Hildesheim as a son of the minister August Heinrich Link (1738–1783), who taught him love ...

settled on the name ''Amanita phalloides'', after Persoon had named it ''Amanita viridis'' 30 years earlier. Although Louis Secretan's use of the name ''A. phalloides'' predates Link's, it has been rejected for nomenclatural purposes because Secretan's works did not use binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

consistently; some taxonomists have, however, disagreed with this opinion.

''Amanita phalloides'' is the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of ''Amanita'' section

Section, Sectioning, or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sig ...

Phalloideae, a group that contains all of the deadly poisonous ''Amanita'' species thus far identified. Most notable of these are the species known as destroying angel

The name destroying angel applies to several similar, closely related species of deadly all-white mushrooms in the genus ''Amanita''. They are '' Amanita virosa'' in Europe and '' A. bisporigera'' and '' A. ocreata'' in eastern and western North ...

s, namely '' A. virosa'', '' A. bisporigera'' and '' A. ocreata'', as well as the fool's mushroom ''( A. verna)''. The term "destroying angel" has been applied to ''A. phalloides'' at times, but "death cap" is by far the most common vernacular name used in English. Other common names also listed include "stinking amanita" and "deadly amanita".Benjamin, p.203

A rarely appearing, all-white form was initially described ''A. phalloides'' f. ''alba'' by Max Britzelmayr,Jordan & Wheeler, p. 109 though its status has been unclear. It is often found growing amid normally colored death caps. It has been described, in 2004, as a distinct variety and includes what was termed ''A. verna'' var. ''tarda''. The true ''A. verna'' fruits in spring and turns yellow with KOH solution, whereas ''A. phalloides'' never does.

Description

The death cap has a large and imposingepigeous

Epigeal, epigean, epigeic and epigeous are biological terms describing an organism's activity above the soil surface.

In botany, a seed is described as showing epigeal germination when the cotyledons of the germinating seed expand, throw off the ...

(aboveground) fruiting body

The sporocarp (also known as fruiting body, fruit body or fruitbody) of fungi is a multicellular structure on which spore-producing structures, such as basidia or asci, are borne. The fruitbody is part of the sexual phase of a fungal life cyc ...

(basidiocarp), usually with a pileus (cap) from 5 to 15 cm across (2 to 5.8 inches) across, initially rounded and hemispherical, but flattening with age. The color of the cap can be pale-green, yellowish-green, olive-green, bronze, or (in one form) white; it is often paler toward the margins, which can have darker streaks; it is also often paler after rain. The cap surface is sticky when wet and easily peeled—a troublesome feature, as that is allegedly a feature of edible fungi.Jordan & Wheeler, p.99 The remains of the partial veil

In mycology, a partial veil (also called an inner veil, to differentiate it from the "outer", or universal veil) is a temporary structure of tissue found on the fruiting bodies of some Basidiomycota, basidiomycete fungus, fungi, typically agarics. ...

are seen as a skirtlike, floppy annulus usually about below the cap. The crowded white lamellae

Lamella (: lamellae) means a small plate or flake in Latin, and in English may refer to:

Biology

* Lamella (mycology), a papery rib beneath a mushroom cap

* Lamella (botany)

* Lamella (surface anatomy), a plate-like structure in an animal

* Lame ...

(gills) are free. The stipe is white with a scattering of grayish-olive scales and is long and thick, with a swollen, ragged, sac-like white volva (base). As the volva, which may be hidden by leaf litter

Plant litter (also leaf litter, tree litter, soil litter, litterfall, or duff) is dead plant material (such as leaves, bark, needles, twigs, and cladodes) that has fallen to the ground. This detritus or dead organic material and its constituen ...

, is a distinctive and diagnostic feature, it is important to remove some debris to check for it.Jordan & Wheeler, p.108 Spores: 7-12 x 6-9 μm. Smooth, ellipsoid, amyloid.

The smell has been described as initially faint and honey-sweet, but strengthening over time to become overpowering, sickly-sweet and objectionable.Zeitlmayr, p.61 Young specimens first emerge from the ground resembling a white egg covered by a universal veil, which then breaks, leaving the volva as a remnant. The spore print

300px, Making a spore print of the mushroom ''Volvariella volvacea'' shown in composite: (photo lower half) mushroom cap laid on white and dark paper; (photo upper half) cap removed after 24 hours showing warm orange ("tussock") color spore print. ...

is white, a common feature of ''Amanita''. The transparent spores are globular to egg-shaped, measure 8–10 μm (0.3–0.4 mil) long, and stain blue with iodine

Iodine is a chemical element; it has symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists at standard conditions as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

. The gills, in contrast, stain pallid lilac or pink with concentrated sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen, ...

.

Biochemistry

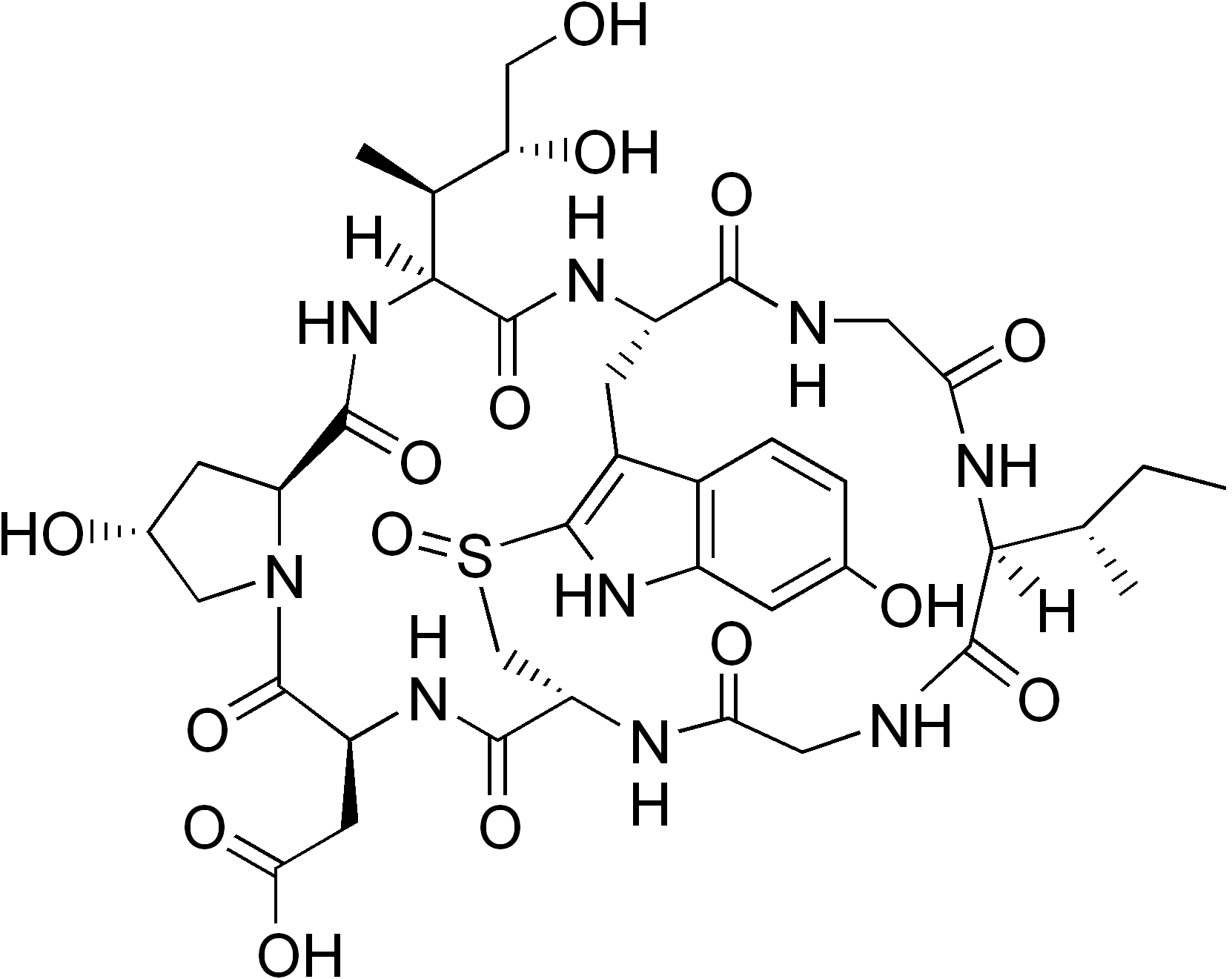

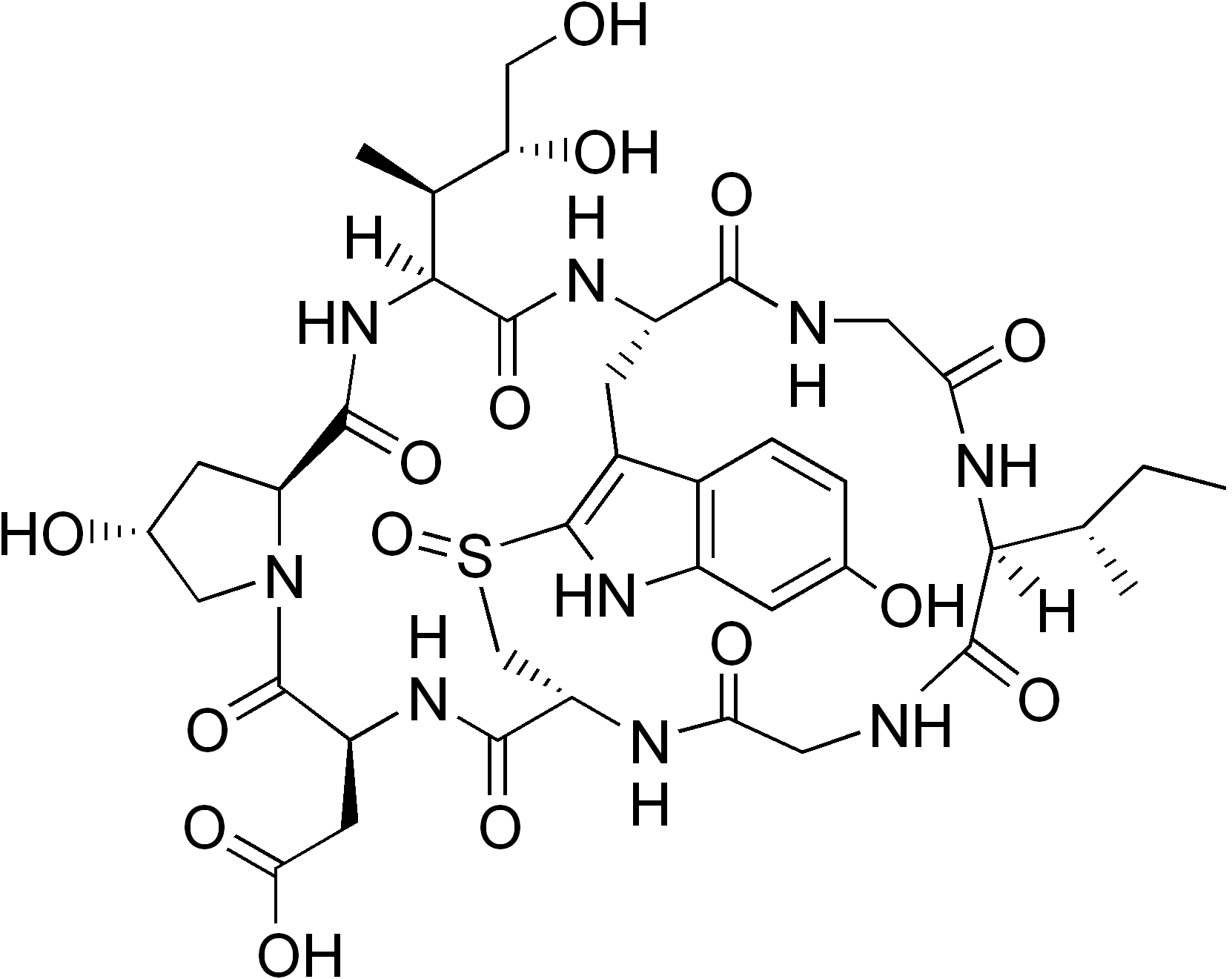

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped)

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped) peptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty am ...

s, spread throughout the mushroom and d cell–destroying activity '' in vitro''. An unrelated compound, antamanide, has also been isolated.

Amatoxins consist of at least eight compounds with a similar structure, that of eight amino-acid rings; they were isolated in 1941 by Heinrich O. Wieland and Rudolf Hallermayer of the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich, LMU or LMU Munich; ) is a public university, public research university in Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Originally established as the University of Ingolstadt in 1472 by Duke ...

. Of the amatoxins, α-Amanitin is the chief component and along with β-amanitin is likely responsible for the toxic effects. Their major toxic mechanism is the inhibition of RNA polymerase II

RNA polymerase II (RNAP II and Pol II) is a Protein complex, multiprotein complex that Transcription (biology), transcribes DNA into precursors of messenger RNA (mRNA) and most small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and microRNA. It is one of the three RNA pol ...

, a vital enzyme in the synthesis of messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

(mRNA), microRNA

Micro ribonucleic acid (microRNA, miRNA, μRNA) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules containing 21–23 nucleotides. Found in plants, animals, and even some viruses, miRNAs are involved in RNA silencing and post-transcr ...

, and small nuclear RNA (snRNA

Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the splicing speckles and Cajal bodies of the cell nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The length of an average snRNA is approximately 150 nucleotides. They are transcrib ...

). Without mRNA, essential protein synthesis

Protein biosynthesis, or protein synthesis, is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via degradation or export) through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critica ...

and hence cell metabolism grind to a halt and the cell dies. The liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

is the principal organ affected, as it is the organ which is first encountered after absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, though other organs, especially the kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

s, are susceptible.Benjamin, p.217 The RNA polymerase of ''Amanita phalloides'' is insensitive to the effects of amatoxins, so the mushroom does not poison itself.

The phallotoxins consist of at least seven compounds, all of which have seven similar peptide rings. Phalloidin

Phalloidin belongs to a class of toxins called phallotoxins, which are found in the death cap mushroom ''( Amanita phalloides)''. It is a rigid bicyclic heptapeptide that is lethal after a few days when injected into the bloodstream. The major s ...

was isolated in 1937 by Feodor Lynen

Feodor Felix Konrad Lynen (; 6 April 1911 – 6 August 1979) was a German biochemist. In 1964 he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine together with Konrad Bloch for their discoveries concerning the mechanism and regulation of cholestero ...

, Heinrich Wieland's student and son-in-law, and Ulrich Wieland of the University of Munich. Though phallotoxins are highly toxic to liver cells, they have since been found to add little to the death cap's toxicity, as they are not absorbed through the gut. Furthermore, phalloidin is also found in the edible (and sought-after) blusher

The blusher is the common name for several closely related species of the genus ''Amanita''. ''A. rubescens'' (the blushing amanita) is found in Eurasia and ''A. novinupta'' (the new bride blushing amanita or blushing bride) is found ...

(''A. rubescens''). Another group of minor active peptides are the virotoxins, which consist of six similar monocyclic heptapeptides. Like the phallotoxins, they do not induce any acute toxicity after ingestion in humans.

The genome of the death cap has been sequenced.

Similarity to edible species

''A. phalloides'' is similar to the edible paddy straw mushroom ('' Volvariella volvacea'')Benjamin, pp.198–199 and '' A. princeps'', commonly known as "white Caesar". Some may mistake juvenile death caps for ediblepuffball

Puffballs are a type of fungus featuring a ball-shaped fruit body that (when mature) bursts on contact or impact, releasing a cloud of dust-like spores into the surrounding area. Puffballs belong to the division Basidiomycota and encompass sever ...

s or mature specimens for other edible ''Amanita'' species, such as '' A. lanei'', so some authorities recommend avoiding the collecting of ''Amanita'' species for the table altogether. The white form of ''A. phalloides'' may be mistaken for edible species of ''Agaricus

''Agaricus'' is a genus of mushroom-forming fungi containing both edible and poisonous species, with over 400 members worldwide and possibly again as many disputed or newly discovered species. The genus includes the common ("button") mushroom ...

'', especially the young fruitbodies whose unexpanded caps conceal the telltale white gills; all mature species of ''Agaricus'' have dark-colored gills.

In Europe, other similarly green-capped species collected by mushroom hunters include various green-hued brittlegills of the genus ''Russula

''Russula'' is a very large genus composed of around 750 worldwide species of fungi. The genus was described by Christian Hendrik Persoon in 1796.

The mushrooms are fairly large, and brightly colored – making them one of the most recognizable ...

'' and the formerly popular '' Tricholoma equestre'', now regarded as hazardous owing to a series of restaurant poisonings in France. Brittlegills, such as '' Russula heterophylla'', '' R. aeruginea'', and '' R. virescens'', can be distinguished by their brittle flesh and the lack of both volva and ring.Zeitlmayr, p.62 Other similar species include '' A. subjunquillea'' in eastern Asia and '' A. arocheae'', which ranges from Andean

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long and wide (widest between 18°S ...

Colombia north at least as far as central Mexico, both of which are also poisonous.

Distribution and habitat

The death cap is native to Europe, where it is widespread. It is found from the southern coastal regions of Scandinavia in the north, to Ireland in the west, east to Poland and western Russia, and south throughout the Balkans, in Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal in the Mediterranean basin, and in Morocco and Algeria in north Africa. In west Asia, it has been reported from forests of northern Iran. There are records from further east in Asia but these have yet to be confirmed as ''A. phalloides''. By the end of the 19th century,Charles Horton Peck

Charles Horton Peck (March 30, 1833 – July 11, 1917) was an American mycologist of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He was the New York State Botanist from 1867 to 1915, a period in which he described over 2,700 species of North American fu ...

had reported ''A. phalloides'' in North America. In 1918, samples from the eastern United States were identified as being a distinct though similar species, '' A. brunnescens'', by George Francis Atkinson of Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

. By the 1970s, it had become clear that ''A. phalloides'' does occur in the United States, apparently having been introduced from Europe alongside chestnuts, with populations on the West and East Coasts.Benjamin, p.204 A 2006 historical review concluded the East Coast populations were inadvertently introduced, likely on the roots of other purposely imported plants such as chestnuts. The origins of the West Coast populations remained unclear, due to scant historical records, but a 2009 genetic study provided strong evidence for the introduced status of the fungus on the west coast of North America. Observations of various collections of ''A. phalloides'', from conifers rather than native forests, have led to the hypothesis that the species was introduced to North America multiple times. It is hypothesized that the various introductions led to multiple genotypes which are adapted to either oaks or conifers.

''A. phalloides'' were conveyed to new countries across the Southern Hemisphere with the importation of hardwoods and conifers in the late twentieth century. Introduced oaks appear to have been the vector to Australia and South America; populations under oaks have been recorded from Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

, Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

(where two people died in January 2012, of four who were poisoned), Adelaide

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

, and further observed by citizen scientists in Beechworth, Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

and Albury

Albury (; ) is a major regional city that is located in the Murray River, Murray region of New South Wales, Australia. It is part of the twin city of Albury–Wodonga, Albury-Wodonga and is located on the Hume Highway and the northern side of ...

.

It has been recorded under other introduced trees in Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

. Pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

plantations are associated with the fungus in Tanzania and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, found under oaks and poplars in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, as well as Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

.

A number of deaths in India have been attributed to it.

Ecology

It isectomycorrhiza

An ectomycorrhiza (from Greek ἐκτός ', "outside", μύκης ', "fungus", and ῥίζα ', "root"; ectomycorrhizas or ectomycorrhizae, abbreviated EcM) is a form of symbiotic relationship that occurs between a fungal symbiont, or mycobio ...

lly associated with several tree species and is symbiotic with them. In Europe, these include hardwood

Hardwood is wood from Flowering plant, angiosperm trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal ecosystem, boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostl ...

and, less frequently, conifer

Conifers () are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a sin ...

species. It appears most commonly under oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

s, but also under beech

Beech (genus ''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to subtropical (accessory forest element) and temperate (as dominant element of Mesophyte, mesophytic forests) Eurasia and North America. There are 14 accepted ...

es, chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

Description

...

s, horse-chestnuts, birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

es, filberts, hornbeam

Hornbeams are hardwood trees in the plant genus ''Carpinus'' in the family Betulaceae. Its species occur across much of the temperateness, temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

Common names

The common English name ''hornbeam'' derives ...

s, pines, and spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' ( ), a genus of about 40 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal ecosystem, boreal (taiga) regions of the Northern hemisphere. ''Picea'' ...

s. In other areas, ''A. phalloides'' may also be associated with these trees or with only some species. In coastal California, for example, ''A. phalloides'' is associated with coast live oak

''Quercus agrifolia'', the California live oak, or coast live oak, is an evergreen live oak native to the California Floristic Province. Live oaks are so-called because they keep living leaves on the tree all year, adding young leaves and sheddi ...

. In countries where it has been introduced, it has been restricted to those exotic trees with which it would associate in its natural range. There is, however, evidence of ''A. phalloides'' associating with hemlock and with genera of the Myrtaceae

Myrtaceae (), the myrtle family, is a family of dicotyledonous plants placed within the order Myrtales. Myrtle, pōhutukawa, bay rum tree, clove, guava, acca (feijoa), allspice, and eucalyptus are some notable members of this group. All ...

: ''Eucalyptus

''Eucalyptus'' () is a genus of more than 700 species of flowering plants in the family Myrtaceae. Most species of ''Eucalyptus'' are trees, often Mallee (habit), mallees, and a few are shrubs. Along with several other genera in the tribe Eucalyp ...

'' in Tanzania and Algeria, and ''Leptospermum

''Leptospermum'' is a genus of shrubs and small trees in the myrtle family Myrtaceae commonly known as tea trees, although this name is sometimes also used for some species of ''Melaleuca''. Most species are endemic to Australia, with the greate ...

'' and ''Kunzea

''Kunzea'' is a genus of plants in the family Myrtaceae and is Endemism, endemic to Australasia. They are shrubs, sometimes small trees and usually have small, crowded, rather Aroma compound, aromatic leaves. The flowers are similar to those of p ...

'' in New Zealand, suggesting that the species may have invasive potential. It may have also been anthropogenically introduced to the island of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, where it has been documented to fruit within ''Corylus avellana

''Corylus avellana'', the common hazel, is a species of flowering plant in the birch tree, birch family Betulaceae. The shrubs usually grow tall. The nut is round, in contrast to the longer Corylus maxima, filbert nut. Common hazel is native to E ...

'' plantations.

Toxicity

The fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal

The fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisoning

Mushroom poisoning is poisoning resulting from the ingestion of mushrooms that contain toxicity, toxic substances. Signs and symptoms, Symptoms can vary from slight Gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal discomfort to death in about 10 days. Mus ...

s worldwide. Its biochemistry has been researched intensively for decades, and , or half a cap, of this mushroom is estimated to be enough to kill a human.Benjamin, p.211 On average, one person dies a year in North America from death cap ingestion. The toxins of the death cap mushrooms primarily target the liver, but other organs, such as the kidneys, are also affected. Symptoms of death cap mushroom toxicity usually occur 6 to 12 hours after ingestion. Symptoms of ingestion of the death cap mushroom may include nausea and vomiting, which is then followed by jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

, seizures, and coma which will lead to death. The mortality rate of ingestion of the death cap mushroom is believed to be around 10–30%.

Some authorities strongly advise against putting suspected death caps in the same basket with fungi collected for the table and to avoid even touching them. Furthermore, the toxicity is not reduced by cooking, freezing, or drying.

Poisoning incidents usually result from errors in identification. Recent cases highlight the issue of the similarity of ''A. phalloides'' to the edible paddy straw mushroom (''Volvariella volvacea''), with East- and Southeast-Asian immigrants in Australia and the West Coast of the U.S. falling victim. In an episode in Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

, four members of a Korean family required liver transplant

Liver transplantation or hepatic transplantation is the replacement of a Liver disease, diseased liver with the healthy liver from another person (allograft). Liver transplantation is a treatment option for Cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and ...

s. Many North American incidents of death cap poisoning have occurred among Laotian and Hmong

Hmong may refer to:

* Hmong people, an ethnic group living mainly in Southwest China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand

* Hmong cuisine

* Hmong customs and culture

** Hmong music

** Hmong textile art

* Hmong language, a continuum of closely related ...

immigrants, since it is easily confused with ''A. princeps'' ("white Caesar"), a popular mushroom in their native countries. Of the nine people poisoned in Australia's Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

region between 1988 and 2011, three were from Laos

Laos, officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR), is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Myanmar and China to the northwest, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the southeast, and Thailand to the west and ...

and two were from China. In January 2012, four people were accidentally poisoned when death caps (reportedly misidentified as straw mushrooms, which are popular in Chinese and other Asian dishes) were served for dinner in Canberra; all the victims required hospital treatment and two of them died, with a third requiring a liver transplant.

Detection

The so-called Meixner test is used to detect the presence of amatoxins in a sample. The test givesfalse positive

A false positive is an error in binary classification in which a test result incorrectly indicates the presence of a condition (such as a disease when the disease is not present), while a false negative is the opposite error, where the test resu ...

results for psilocin

Psilocin, also known as 4-hydroxy-''N'',''N''-dimethyltryptamine (4-HO-DMT), is a substituted tryptamine alkaloid and a serotonergic psychedelic. It is present in most psychedelic mushrooms together with its phosphorylated counterpart psilocy ...

, psilocybin

Psilocybin, also known as 4-phosphoryloxy-''N'',''N''-dimethyltryptamine (4-PO-DMT), is a natural product, naturally occurring tryptamine alkaloid and Investigational New Drug, investigational drug found in more than List of psilocybin mushroom ...

, and 5-substituted tryptamines.

Signs and symptoms

Death caps have been reported to taste pleasant. This, coupled with the delay in the appearance of symptoms—during which time internal organs are being severely, sometimes irreparably, damaged—makes them particularly dangerous. Initially, symptoms aregastrointestinal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

in nature and include colicky abdominal pain, with watery diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

, nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. It can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Over 30 d ...

, and vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis, puking and throwing up) is the forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis, pre ...

, which may lead to dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds intake, often resulting from excessive sweating, health conditions, or inadequate consumption of water. Mild deh ...

if left untreated, and, in severe cases, hypotension

Hypotension, also known as low blood pressure, is a cardiovascular condition characterized by abnormally reduced blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood and is ...

, tachycardia

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate. In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults. Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal ...

, hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia (American English), also spelled hypoglycaemia or hypoglycæmia (British English), sometimes called low blood sugar, is a fall in blood sugar to levels below normal, typically below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L). Whipple's tria ...

, and acid–base disturbances. These first symptoms resolve two to three days after the ingestion. A more serious deterioration signifying liver involvement may then occur—jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

, diarrhea, delirium

Delirium (formerly acute confusional state, an ambiguous term that is now discouraged) is a specific state of acute confusion attributable to the direct physiological consequence of a medical condition, effects of a psychoactive substance, or ...

, seizures

A seizure is a sudden, brief disruption of brain activity caused by abnormal, excessive, or synchronous neuronal firing. Depending on the regions of the brain involved, seizures can lead to changes in movement, sensation, behavior, awareness, o ...

, and coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to Nociception, respond normally to Pain, painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal Circadian rhythm, sleep-wake cycle and does not initiate ...

due to fulminant liver failure and attendant hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is an altered level of consciousness as a result of liver failure. Its onset may be gradual or sudden. Other symptoms may include movement problems, changes in mood, or changes in personality. In the advanced stag ...

caused by the accumulation of normally liver-removed substances in the blood. Kidney failure

Kidney failure, also known as renal failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney fa ...

(either secondary to severe hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver parenchyma, liver tissue. Some people or animals with hepatitis have no symptoms, whereas others develop yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice), Anorexia (symptom), poor appetite ...

or caused by direct toxic kidney damage) and coagulopathy

Coagulopathy (also called a bleeding disorder) is a condition in which the blood's ability to coagulate (form clots) is impaired. This condition can cause a tendency toward prolonged or excessive bleeding ( bleeding diathesis), which may occur s ...

may appear during this stage. Life-threatening complications include increased intracranial pressure

Intracranial pressure (ICP) is the pressure exerted by fluids such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inside the skull and on the brain tissue. ICP is measured in millimeters of mercury ( mmHg) and at rest, is normally 7–15 mmHg for a supine adu ...

, intracranial bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethr ...

, pancreatic inflammation, acute kidney failure

Acute may refer to: Language

* Acute accent, a diacritic used in many modern written languages

* Acute (phonetic), a perceptual classification

Science and mathematics

* Acute angle

** Acute triangle

** Acute, a leaf shape in the glossary of leaf m ...

, and cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest (also known as sudden cardiac arrest CA is when the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops beating. When the heart stops beating, blood cannot properly Circulatory system, circulate around the body and the blood flow to the ...

. Death generally occurs six to sixteen days after the poisoning.

It is noticed that after up to 24 hours have passed, the symptoms seem to disappear and the person might feel fine for up to 72 hours. Symptoms of liver and kidney damage start 3 to 6 days after the mushrooms were eaten, with the considerable increase of the transaminases.

Mushroom poisoning is more common in Europe than in North America. Up to the mid-20th century, the mortality rate was around 60–70%, but this has been greatly reduced with advances in medical care. A review of death cap poisoning throughout Europe from 1971 to 1980 found the overall mortality rate to be 22.4% (51.3% in children under ten and 16.5% in those older than ten). This was revised to around 10–15% in surveys reviewed in 1995.Benjamin, p.215

Treatment

Consumption of the death cap is amedical emergency

A medical emergency is an acute injury or illness that poses an immediate risk to a person's life or long-term health, sometimes referred to as a situation risking "life or limb". These emergencies may require assistance from another, qualified ...

requiring hospitalization. The four main categories of therapy for poisoning are preliminary medical care, supportive measures, specific treatments, and liver transplantation.

Preliminary care consists of gastric decontamination with either activated carbon

Activated carbon, also called activated charcoal, is a form of carbon commonly used to filter contaminants from water and air, among many other uses. It is processed (activated) to have small, low-volume pores that greatly increase the surface ar ...

or gastric lavage

Gastric lavage, also commonly called stomach pumping or gastric irrigation or gastric suction, is the process of cleaning out the contents of the stomach using a tube. Since its first recorded use in the early 19th century, it has become one of the ...

; due to the delay between ingestion and the first symptoms of poisoning, it is common for patients to arrive for treatment many hours after ingestion, potentially reducing the efficacy of these interventions. Supportive measures are directed towards treating the dehydration which results from fluid loss during the gastrointestinal phase of intoxication and correction of metabolic acidosis

Metabolic acidosis is a serious electrolyte disorder characterized by an imbalance in the body's acid-base balance. Metabolic acidosis has three main root causes: increased acid production, loss of bicarbonate, and a reduced ability of the kidn ...

, hypoglycemia, electrolyte

An electrolyte is a substance that conducts electricity through the movement of ions, but not through the movement of electrons. This includes most soluble Salt (chemistry), salts, acids, and Base (chemistry), bases, dissolved in a polar solven ...

imbalances, and impaired coagulation.

No definitive antidote is available, but some specific treatments have been shown to improve survivability. High-dose continuous intravenous penicillin G has been reported to be of benefit, though the exact mechanism is unknown, and trials with cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus '' Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibio ...

s show promise.Benjamin, p.227 Some evidence indicates intravenous silibinin, an extract from the blessed milk thistle (''Silybum marianum''), may be beneficial in reducing the effects of death cap poisoning. A long-term clinical trial of intravenous silibinin began in the US in 2010. Silibinin prevents the uptake of amatoxins by liver cells

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, bile ...

, thereby protecting undamaged liver tissue; it also stimulates DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, leading to an increase in RNA synthesis. According to one report based on a treatment of 60 patients with silibinin, patients who started the drug within 96 hours of ingesting the mushroom and who still had intact kidney function all survived. As of February 2014 supporting research has not yet been published.

SLCO1B3

Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B3 (SLCO1B3) also known as organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B3 (OATP1B3) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''SLCO1B3'' gene.

OATP1B3 is a 12-transmembrane domain influx tr ...

has been identified as the human hepatic uptake transporter for amatoxins; moreover, substrates and inhibitors of that protein—among others rifampicin

Rifampicin, also known as rifampin, is an ansamycin antibiotic used to treat several types of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis (TB), ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, leprosy, and Legionnaires' disease. It is almost always used tog ...

, penicillin, silibinin, antamanide, paclitaxel

Paclitaxel, sold under the brand name Taxol among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat ovarian cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical cancer, and pancreatic cancer. It is administered b ...

, ciclosporin

Ciclosporin, also spelled cyclosporine and cyclosporin, is a calcineurin inhibitor, used as an immunosuppressant medication. It is taken Oral administration, orally or intravenously for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn's disease, nephr ...

and prednisolone

Prednisolone is a corticosteroid, a steroid hormone used to treat certain types of allergies, inflammation, inflammatory conditions, autoimmune disorders, and cancers, Electrolyte imbalance, electrolyte imbalances and skin conditions. Some of ...

—may be useful for the treatment of human amatoxin poisoning.

N-acetylcysteine

''N''-acetylcysteine, also known as Acetylcysteine and NAC, is a mucolytics that is used to treat paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose and to loosen thick mucus in individuals with chronic bronchopulmonary disorders, such as pneumonia and ...

has shown promise in combination with other therapies. Animal studies indicate the amatoxins deplete hepatic glutathione

Glutathione (GSH, ) is an organic compound with the chemical formula . It is an antioxidant in plants, animals, fungi, and some bacteria and archaea. Glutathione is capable of preventing damage to important cellular components caused by sources ...

; N-acetylcysteine serves as a glutathione precursor and may therefore prevent reduced glutathione levels and subsequent liver damage. None of the antidotes used have undergone prospective, randomized clinical trial

A randomized controlled trial (or randomized control trial; RCT) is a form of scientific experiment used to control factors not under direct experimental control. Examples of RCTs are clinical trials that compare the effects of drugs, surgical t ...

s, and only anecdotal support is available. Silibinin and N-acetylcysteine appear to be the therapies with the most potential benefit. Repeated doses of activated carbon may be helpful by absorbing any toxins returned to the gastrointestinal tract following enterohepatic circulation

Enterohepatic circulation is the circulation of biliary acids, bilirubin, drugs or other substances from the liver to the bile, followed by entry into the small intestine, absorption by the enterocyte and transport back to the liver. Enterohepa ...

. Other methods of enhancing the elimination of the toxins have been trialed; techniques such as hemodialysis

Hemodialysis, American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, also spelled haemodialysis, or simply ''"'dialysis'"'', is a process of filtering the blood of a person whose kidneys are not working normally. This type of Kidney dialys ...

, hemoperfusion

Hemoperfusion or hæmoperfusion (see spelling differences) is a method of filtering the blood extracorporeally (that is, outside the body) to remove a toxin. As with other extracorporeal methods, such as hemodialysis (HD), hemofiltration (HF), an ...

, plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis (from the Greek language, Greek πλάσμα, ''plasma'', something molded, and ἀφαίρεσις ''aphairesis'', taking away) is the removal, treatment, and return or exchange of blood plasma or components thereof from and to the ...

, and peritoneal dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a type of kidney dialysis, dialysis that uses the peritoneum in a person's abdomen as the membrane through which fluid and dissolved substances are exchanged with the blood. It is used to remove excess fluid, correct e ...

have occasionally yielded success, but overall do not appear to improve outcome.

In patients developing liver failure, a liver transplant is often the only option to prevent death. Liver transplants have become a well-established option in amatoxin poisoning. This is a complicated issue, however, as transplants themselves may have significant complications and mortality; patients require long-term immunosuppression

Immunosuppression is a reduction of the activation or efficacy of the immune system. Some portions of the immune system itself have immunosuppressive effects on other parts of the immune system, and immunosuppression may occur as an adverse react ...

to maintain the transplant. That being the case, the criteria have been reassessed, such as onset of symptoms, prothrombin time

The prothrombin time (PT) – along with its derived measures of prothrombin ratio (PR) and international normalized ratio (INR) – is an assay for evaluating the Coagulation#Extrinsic pathway, extrinsic pathway and Coagulation#Common pathway, ...

(PT), serum bilirubin

Bilirubin (BR) (adopted from German, originally bili—bile—plus ruber—red—from Latin) is a red-orange compound that occurs in the normcomponent of the straw-yellow color in urine. Another breakdown product, stercobilin, causes the brown ...

, and presence of encephalopathy

Encephalopathy (; ) means any disorder or disease of the brain, especially chronic degenerative conditions. In modern usage, encephalopathy does not refer to a single disease, but rather to a syndrome of overall brain dysfunction; this syndrome ...

, for determining at what point a transplant becomes necessary for survival. Evidence suggests, although survival rates have improved with modern medical treatment, in patients with moderate to severe poisoning, up to half of those who did recover suffered permanent liver damage.Benjamin, pp.231–232 A follow-up study has shown most survivors recover completely without any sequelae if treated within 36 hours of mushroom ingestion.

Notable victims

Several historical figures may have died from ''A. phalloides'' poisoning (or other similar, toxic ''Amanita'' species). These were either accidental poisonings orassassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

plots. Alleged victims of this kind of poisoning include Roman Emperor Claudius, Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate o ...

, the Russian tsaritsa Natalia Naryshkina, and Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI.

R. Gordon Wasson recounted the details of these deaths, noting the likelihood of ''Amanita'' poisoning. In the case of Clement VII, the illness that led to his death lasted five months, making the case inconsistent with amatoxin poisoning. Natalya Naryshkina is said to have consumed a large quantity of pickled mushrooms prior to her death. It is unclear whether the mushrooms themselves were poisonous or if she succumbed to food poisoning

Foodborne illness (also known as foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the contamination of food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease), and toxins such ...

.

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI experienced indigestion after eating a dish of Sautéing, sautéed mushrooms. This led to an illness from which he died 10 days later—symptomatology consistent with amatoxin poisoning. His death led to the War of the Austrian Succession. Noted Voltaire, "this mushroom dish has changed the destiny of Europe."Benjamin, p.35

The case of Claudius's poisoning is more complex. Claudius was known to have been very fond of eating Caesar's mushroom. Following his death, many sources have attributed it to his being fed a meal of death caps instead of Caesar's mushrooms. Ancient authors, such as Tacitus and Suetonius, are unanimous about poison having been added to the mushroom dish, rather than the dish having been prepared from poisonous mushrooms. Wasson speculated the poison used to kill Claudius was derived from death caps, with a fatal dose of an unknown poison (possibly a variety of nightshade) being administered later during his illness.Benjamin, pp.33–34 Other historians have speculated that Claudius may have died of natural causes.

In July 2023, four people in Leongatha, Australia, were taken to hospital after consuming beef Wellington which contained ''A. phalloides''. Three of the four guests subsequently died while one survived, later receiving a liver transplantation, liver transplant. The woman who cooked the meal, Erin Patterson, was 2023 Leongatha mushroom poisoning, charged with murder in November 2023. As of June 2025, her trial is ongoing.

See also

*List of Amanita species, List of ''Amanita'' species *List of deadly fungi * , known for expertise in treating mushroom poisoningReferences

Cited texts

* * *External links

UK Telegraph Newspaper (September 2008) - One woman dead, another critically ill after eating Death Cap fungi

* [http://www.mushroomexpert.com/amanita_phalloides.html ''Amanita phalloides'': the death cap]

''Amanita phalloides'': Invasion of the Death Cap

* [http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Amanita_phalloides.html California Fungi—Amanita phalloides]

Death cap in Australia - ANBG website

On the Trail of the Death Cap Mushroom

from National Public Radio * {{Authority control Amanita, phalloides Fungi of Africa Fungi of Europe Deadly fungi Hepatotoxins Fungi described in 1821 Fungus species