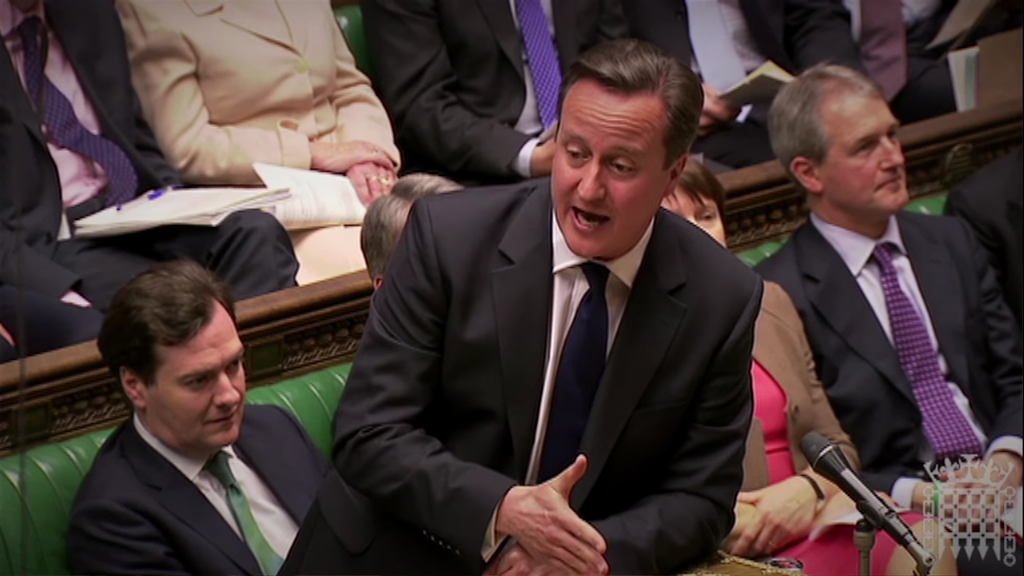

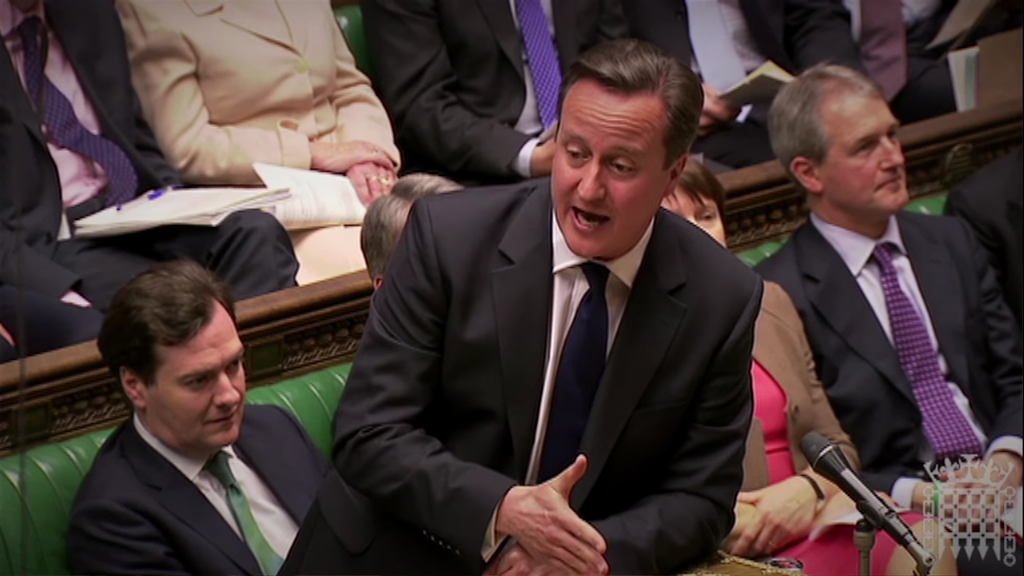

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK since 1945 and resigned after a

referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

supported the country's

leaving the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

. After

his premiership, he served as

Foreign Secretary in the government of prime minister

Rishi Sunak

Rishi Sunak (born 12 May 1980) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2022 to 2024. Following his defeat to Keir Starmer's La ...

from 2023 to 2024. Cameron was

Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016 and served as

Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

from 2005 to 2010. He was

Member of Parliament (MP) for

Witney

Witney is a market town on the River Windrush in West Oxfordshire in the county of Oxfordshire, England. It is west of Oxford.

History

The Toponymy, place-name "Witney" is derived from the Old English for "Witta's island". The earliest kno ...

from 2001 to 2016, and has been a member of the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

since November 2023. Cameron identifies as a

one-nation conservative and has been associated with both

economically liberal and

socially liberal policies.

Born in London to an upper-middle-class family, Cameron was educated at

Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

and

Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The l ...

. After becoming an MP in 2001, he served in the opposition

Shadow Cabinet under Conservative leader

Michael Howard

Michael Howard, Baron Howard of Lympne (born Michael Hecht; 7 July 1941) is a British politician who was Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposi ...

, and

succeeded Howard in 2005. Following the

2010 general election,

negotiations led to Cameron becoming prime minister as the head of

a coalition government with the

Liberal Democrats.

His premiership was marked by the effects of the

2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

and the

Great Recession

The Great Recession was a period of market decline in economies around the world that occurred from late 2007 to mid-2009. , which his government sought to address through

austerity measures

In economic policy, austerity is a set of political-economic policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits through spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both. There are three primary types of austerity measures: high ...

. His administration passed the

Health and Social Care Act and the

Welfare Reform Act, which introduced large-scale changes to

healthcare

Health care, or healthcare, is the improvement or maintenance of health via the preventive healthcare, prevention, diagnosis, therapy, treatment, wikt:amelioration, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other disability, physic ...

and

welfare. It also attempted to enforce stricter immigration policies via the

Home Office hostile environment policy, introduced reforms to education under

Michael Gove as Education Secretary and oversaw the

2012 London Olympics. Cameron's administration privatised

Royal Mail

Royal Mail Group Limited, trading as Royal Mail, is a British postal service and courier company. It is owned by International Distribution Services. It operates the brands Royal Mail (letters and parcels) and Parcelforce Worldwide (parcels) ...

and some other state assets, and legalised

same-sex marriage in England and Wales

Same-sex marriage is legal in all parts of the United Kingdom. As marriage is a devolved legislative matter, different parts of the United Kingdom legalised at different times; it has been recognised and performed in England and Wales since Ma ...

. Internationally, Cameron oversaw

Operation Ellamy

Operation Ellamy was the codename for the United Kingdom participation in the 2011 military intervention in Libya. The operation was part of an international coalition aimed at enforcing a Libyan no-fly zone in accordance with the United Natio ...

in the

First Libyan Civil War

The Libyan civil war, also known as the First Libyan Civil War and Libyan Revolution, was an armed conflict in 2011 in the North African country of Libya that was fought between forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and rebel groups that were ...

and authorised the bombing of the

Islamic State

The Islamic State (IS), also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Daesh, is a transnational Salafi jihadism, Salafi jihadist organization and unrecognized quasi-state. IS ...

in Syria. Domestically, his government oversaw the

2011 United Kingdom Alternative Vote referendum

The United Kingdom Alternative Vote referendum, also known as the UK-wide referendum on the Parliamentary voting system was held on Thursday 5 May 2011 in the United Kingdom to choose the method of electing MPs at subsequent general elections. ...

and

Scottish independence referendum, both of which confirmed Cameron's favoured outcome. When the Conservatives secured an unexpected majority in the

2015 general election, he remained as prime minister, this time leading a Conservative-only government known as the

Second Cameron ministry. Cameron introduced

a referendum on the

UK's continuing membership of the European Union in 2016. He supported the

Britain Stronger in Europe

Britain Stronger in Europe (formally The In Campaign Limited) was an advocacy group which campaigned in favour of the United Kingdom's continued membership of the European Union in the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, ...

campaign which lost. Following the success of

Vote Leave, Cameron resigned as prime minister and was succeeded by

Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Baroness May of Maidenhead (; ; born 1 October 1956), is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served as Home Secretar ...

, his Home Secretary.

Cameron resigned his seat on 12 September 2016, and maintained a low political profile. He served as the president of

Alzheimer's Research UK from 2017 to 2023, and was implicated in the

Greensill scandal. Cameron released his memoir,

''For the Record'', in 2019. In 2023 he was appointed Foreign Secretary by

Rishi Sunak

Rishi Sunak (born 12 May 1980) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2022 to 2024. Following his defeat to Keir Starmer's La ...

and became a

life peer

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the peerage whose titles cannot be inherited, in contrast to hereditary peers. Life peers are appointed by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister. With the exception of the D ...

as Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton. His tenure as Foreign Secretary was dominated by the

Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

, the

Gaza war

The Gaza war is an armed conflict in the Gaza Strip and southern Israel fought since 7 October 2023. A part of the unresolved Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Israeli–Palestinian and Gaza–Israel conflict, Gaza–Israel conflicts dating ...

, and the

Gaza humanitarian crisis. After the Conservatives lost the

2024 general election to the

Labour Party, Cameron retired from frontline politics. However, he maintains his

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

seat.

As prime minister, Cameron was credited for helping to modernise the Conservative Party and for reducing the UK's national deficit. However, he was subject to criticism for austerity measures. In

historical rankings of prime ministers of the United Kingdom, academics and journalists have ranked him in the fourth and third quintiles. Cameron was the first former prime minister to be appointed to a ministerial post since

Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel ( ; 2 July 1903 – 9 October 1995), known as Lord Dunglass from 1918 to 1951 and the Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

in 1970, and the first former prime minister to be raised to the peerage since

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

.

Early life and education

Early family life

David William Donald Cameron was born on 9 October 1966 at the

London Clinic in

Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also ) is an area in London, England, and is located in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. Oxford Street forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropo ...

, London,

and raised at

Peasemore in Berkshire.

He has two sisters and an elder brother,

Alexander Cameron.

Cameron is the younger son of Ian Donald Cameron, a stockbroker, and his wife Mary Fleur, a retired

Justice of the Peace and the daughter of

Sir William Mount, 2nd Baronet

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir William Malcolm Mount, 2nd Baronet, TD (28 December 1904 – 22 June 1993), was a British Army officer, High Sheriff of Berkshire and maternal grandfather to David Cameron, former UK Prime Minister and leader of the Co ...

. He is also a descendant of

William IV through one of the king's illegitimate children.

Cameron's father was born at

Blairmore House near

Huntly, Aberdeenshire, and died near

Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

, France, on 8 September 2010; Blairmore was built by Cameron's great-great-grandfather, Alexander Geddes,

who had made a fortune in the

grain trade

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals such as wheat, barley, maize, rice, and other food grains. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other agri ...

in Chicago, Illinois, before returning to Scotland in the 1880s.

Blairmore was sold soon after Ian's birth.

Cameron has said: "On my mother's side of the family, her mother was a Llewellyn, so

Welsh. I'm a real mixture of

Scottish, Welsh and English." He has also referenced the

German Jewish

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321 CE, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish commu ...

ancestry of one of his great-grandfathers, Arthur Levita, a descendant of the

Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

author

Elia Levita

Elia Levita (13 February 146928 January 1549) (), also known as Elijah Levita, Elias Levita, Élie Lévita, Elia Levita Ashkenazi, Eliahu Levita, Eliyahu haBahur ("Elijah the Bachelor"), Elye Bokher, was a Renaissance Hebrew grammarian, schol ...

.

Education

Cameron was educated at two

private schools

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their financial endowme ...

. From the age of seven, he was taught at

Heatherdown School

Heatherdown School, formally called Heatherdown Preparatory School, was an independent preparatory school for boys, near Ascot, in the English county of Berkshire. Set in of grounds, it typically taught between eighty and ninety boys betwee ...

in

Winkfield, Berkshire. Owing to good grades, he entered its top academic class almost two years early. At the age of 13, he went on to

Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

in Berkshire, following his father and elder brother.

His early interest was in art. Six weeks before taking his

O level

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), ...

s, he was caught smoking

cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae that is widely accepted as being indigenous to and originating from the continent of Asia. However, the number of species is disputed, with as many as three species be ...

.

He admitted the offence and had not been involved in selling drugs, so he was not expelled; instead he was fined, prevented from leaving the school grounds and given a "

Georgic" (a punishment that involved copying 500 lines of

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

text).

[Elliott and Hanning, p. 32.]

Cameron passed twelve O-levels and then three

A level

The A-level (Advanced Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Education, as well as a school leaving qualification offered by the educational bodies in the United Kingdom and the educational ...

s:

history of art

The history of art focuses on objects made by humans for any number of spiritual, narrative, philosophical, symbolic, conceptual, documentary, decorative, and even functional and other purposes, but with a primary emphasis on its aesthetics ...

; history, in which he was taught by

Michael Kidson; and economics with politics. He obtained three 'A' grades and a '1' grade in the

scholarship level exam in economics and politics.

[Elliott and Hanning, pp. 45–46.] The following autumn, he passed the entrance exam for the

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, and was offered an

exhibition

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibiti ...

at

Brasenose College.

[Elliott and Hanning, p. 46.]

After leaving Eton in 1984 Cameron started a nine-month

gap year

A gap year, also known as a sabbatical year, is a period of time when students take a break from their studies, usually after completing high school or before beginning graduate school. During this time, students engage in a variety of educatio ...

. For three months, he worked as a researcher for his godfather

Tim Rathbone

John Rankin "Tim" Rathbone (17 March 1933 – 12 July 2002) was a British businessman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was the Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for the seat of Lewes (UK Pa ...

, then Conservative MP for

Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. The town is the administrative centre of the wider Lewes (district), district of the same name. It lies on the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse at the point where the river cuts through the Sou ...

, during which time he attended debates in the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

.

[Elliott and Hanning, pp. 46–47.] Through his father, he was then employed for a further three months in Hong Kong by

Jardine Matheson as a 'ship jumper', an administrative post.

[Elliott and Hanning, pp. 47–48.]

Returning from Hong Kong, Cameron visited the then-

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, where he was approached by two Russian men speaking fluent English. He was later told by one of his professors that it was "definitely an attempt" by the

KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

to recruit him.

In October 1985 Cameron began his Bachelor of Arts course in

Philosophy, Politics and Economics

Philosophy, politics and economics, or politics, philosophy and economics (PPE), is an interdisciplinary undergraduate or postgraduate academic degree, degree which combines study from three disciplines. The first institution to offer degrees in P ...

(PPE) at Brasenose College, Oxford.

["Brasenose alumnus becomes Prime Minister"](_blank)

. Brasenose College. No date. Retrieved 2 January 2012. His tutor,

Vernon Bogdanor

Sir Vernon Bernard Bogdanor (; born 16 July 1943) is a British political scientist, historian, and research professor at the Institute for Contemporary British History at King's College London. He is also emeritus professor of politics and go ...

, has described him as "one of the ablest" students he has taught,

with "moderate and sensible Conservative"

political views.

, who shared tutorials with Cameron, remembers him as an outstanding student: "We were doing our best to grasp basic economic concepts. David—there was nobody else who came even close. He would be integrating them with the way the British political system is put together. He could have lectured me on it, and I would have sat there and taken notes." When commenting in 2006 on his former pupil's ideas about a "Bill of Rights" to replace the

Human Rights Act, however, Bogdanor, himself a

Liberal Democrat, said: "I think he is very confused. I've read his speech and it's filled with contradictions. There are one or two good things in it but one glimpses them, as it were, through a mist of misunderstanding".

While at Oxford, Cameron was a member of the

Bullingdon Club, an exclusive all-male dining society with a reputation for an outlandish drinking culture associated with boisterous behaviour and damaging property.

In his 2019 memoir ''

For the Record'', Cameron wrote about being a member of the Bullingdon and its impact on his political career, saying: "When I look now at the

much-reproduced photograph taken of our group of appallingly over-self-confident 'sons of privilege', I cringe. If I had known at the time the grief I would get for that picture, of course I would never have joined. But life isn't like that..." and: "These were also the years after the ITV adaptation of ''

Brideshead Revisited'' when quite a few of us were carried away by the fantasy of an

Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires ''Decli ...

-like Oxford existence." Cameron's period in the Bullingdon Club was examined in a 2009

Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by Channel Four Television Corporation. It is state-owned enterprise, publicly owned but, unlike the BBC, it receives no public funding and is funded en ...

docudrama, ''

When Boris Met Dave'', the title referring to

Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

, another high-profile Conservative Party figure, the then-mayor of London, who had been a member at the same time, and who would go on to be prime minister himself.

Cameron graduated in 1988 with a

first-class BA degree (later promoted to an

MA by seniority).

Early political career

Conservative Research Department

After graduation, Cameron worked for the

Conservative Research Department between September 1988 and 1993. His first brief was Trade and Industry, Energy and Privatisation; he befriended fellow young colleagues, including

Edward Llewellyn,

Ed Vaizey and

Rachel Whetstone. They and others formed a group they called the "

Smith Square set", which was dubbed the "Brat Pack" by the press, though it is better known as the "

Notting Hill set

The term Notting Hill set refers to an informal group of young figures who were in prominent leadership positions in the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party, or close advisory positions around the former Leader of the Conservative Party (UK ...

", a name given to it pejoratively by

Derek Conway

Derek Leslie Conway TD (born 15 February 1953) is an English politician and television presenter. A member of the Conservative Party, Conway served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for the constituency of Shrewsbury and Atcham from 1983 to 199 ...

. In 1991 Cameron was seconded to

Downing Street

Downing Street is a gated street in City of Westminster, Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. In a cul-de-sac situated off Whiteh ...

to work on briefing

John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

for the then twice-weekly sessions of

Prime Minister's Questions

Prime Minister's Questions (PMQs, officially known as Questions to the Prime Minister, while colloquially known as Prime Minister's Question Time) is a constitutional convention (political custom), constitutional convention in the United Kingd ...

. One newspaper gave Cameron the credit for "sharper ...

Despatch box

A despatch box (alternatively dispatch box) is one of several types of boxes used in government business. Despatch boxes primarily include both those sometimes known as Red box (government), red boxes or ministerial boxes, which are used by the ...

performances" by Major,

["Atticus", ''The Sunday Times'', 30 June 1991] which included highlighting for Major "a dreadful piece of

doublespeak" by

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

(then the

Labour Employment spokesman) over the effect of a national

minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. List of countries by minimum wage, Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation b ...

.

["House of Commons 6th series, vol. 193, cols. 1133–34"](_blank)

, ''Hansard''. Retrieved 4 September 2007. He became head of the political section of the Conservative Research Department, and in August 1991 was tipped to follow

Judith Chaplin as political secretary to the prime minister.

["Diary", ''The Times'', 14 August 1991.]

Cameron lost to

Jonathan Hill, who was appointed in March 1992. Instead, he was given the responsibility for briefing Major for his press conferences during the

1992 general election.

[Wood, Nicholas (13 March 1992). "New aide for Prime Minister". ''The Times'' (London).] During the campaign, Cameron was one of the young "brat pack" of party strategists who worked between 12 and 20 hours a day, sleeping in the house of

Alan Duncan in

Gayfere Street,

Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, which had been Major's campaign headquarters during his bid for the Conservative leadership.

["Sleep little babies". ''The Times'' (London). 20 March 1992.] Cameron headed the economic section. It was while working on this campaign that Cameron first worked closely with and befriended

Steve Hilton, who was later to become Director of Strategy during his party leadership.

[Wood, Nicholas (23 March 1992). "Strain starts to show on Major's round the clock 'brat pack. ''The Times'' (London).] The strain of getting up at 04:45 every day was reported to have led Cameron to decide to leave politics in favour of journalism.

["Campaign fall-out". ''The Times''. 30 March 1992.]

Special Adviser to the Chancellor

The Conservatives' unexpected success in the 1992 election led Cameron to hit back at older party members who had criticised him and his colleagues, saying "whatever people say about us, we got the campaign right", and that they had listened to their campaign workers on the ground rather than the newspapers. He revealed he had led other members of the team across Smith Square to jeer at

Transport House, the former Labour headquarters.

[Pierce, Andrew (11 March 1992). "We got it right, say Patten's brat pack". ''The Sunday Times'' (London).] Cameron was rewarded with a promotion to

Special Adviser to the

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

,

Norman Lamont

Norman Stewart Hughson Lamont, Baron Lamont of Lerwick, (born 8 May 1942) is a British politician and former Conservative MP for Kingston-upon-Thames. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1990 until 1993. He was created a life peer i ...

.

["Brats on the move". ''The Times'' (London). 14 April 1992.]

Cameron was working for Lamont at the time of

Black Wednesday, when pressure from currency speculators forced the

pound sterling

Sterling (symbol: £; currency code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound is the main unit of sterling, and the word '' pound'' is also used to refer to the British currency general ...

out of the

European Exchange Rate Mechanism

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as ...

. At the 1992 Conservative Party conference, he had difficulty trying to arrange to brief the speakers in the economic debate, having to resort to putting messages on the internal television system imploring the mover of the motion,

Patricia Morris, to contact him.

["Diary", ''The Times'', 8 October 1992.] Later that month, Cameron joined a delegation of Special Advisers who visited Germany to build better relations with the

Christian Democratic Union; he was reported to be "still smarting" over the

Bundesbank

The Deutsche Bundesbank (, , colloquially Buba, sometimes alternatively abbreviated as BBk or DBB) is the national central bank for Germany within the Eurosystem. It was the German central bank from 1957 to 1998, issuing the Deutsche Mark (DM). ...

's contribution to the economic crisis.

["Peace-mongers". ''The Times'' (London). 20 October 1992.]

Lamont fell out with John Major after Black Wednesday and became highly unpopular with the public. Taxes needed to be raised in the 1993 Budget, and Cameron fed the options Lamont was considering through to

Conservative Campaign Headquarters

The Conservative Campaign Headquarters (CCHQ), formerly known as Conservative Central Office (CCO), is the headquarters of the British Conservative Party, housing its central staff and committee members, including campaign coordinators and man ...

for their political acceptability to be assessed.

[Hencke, David (8 February 1993). "Treasury tax review eyes fuel and children's clothes". ''The Guardian'' (London).] By May 1993, the Conservatives' average poll rating dropped below 30%, where they would remain until the

1997 general election. Major and Lamont's personal ratings also declined dramatically. Lamont's unpopularity did not necessarily affect Cameron, who was considered as a potential "

kamikaze" candidate for the

Newbury by-election, which includes the area where he grew up.

[White, Michael; Wintour, Patrick (26 February 1993). "Points of Order". ''The Guardian'' (London).] However, Cameron decided not to stand.

During the by-election, Lamont gave the response "

Je ne regrette rien" to a question about whether he most regretted claiming to see "the green shoots of recovery" or admitting to "singing in his bath" with happiness at leaving the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. Cameron was identified by one journalist as having inspired this gaffe; it was speculated that the heavy Conservative defeat in Newbury may have cost Cameron his chance of becoming chancellor himself, even though as he was not a member of Parliament he could not have been.

["Careless talk". ''The Times'' (London). 10 May 1993.] Lamont was sacked at the end of May 1993, and decided not to write the usual letter of resignation; Cameron was given the responsibility to issue to the press a statement of self-justification.

[Smith, David; Prescott, Michael (30 May 1993). "Norman Lamont: the final days" (Focus). ''The Sunday Times'' (London).]

Special Adviser to the Home Secretary

After Lamont was sacked, Cameron remained at the

Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry; in a business context, corporate treasury.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be ...

for less than a month before being specifically recruited by

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

Michael Howard

Michael Howard, Baron Howard of Lympne (born Michael Hecht; 7 July 1941) is a British politician who was Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposi ...

. It was commented that he was still "very much in favour"

["No score flaw". ''The Times'' (London). 22 June 1993.] and it was later reported that many at the Treasury would have preferred Cameron to carry on.

[Grigg, John (2 October 1993). "Primed Minister". ''The Times'' (London).] At the beginning of September 1993, he applied to go on Conservative Central Office's list of

prospective parliamentary candidates (PPCs).

["Newbury's finest". ''The Times'' (London). 6 September 1993.]

Cameron was much more socially liberal than Howard but enjoyed working for him. According to

Derek Lewis, then Director-General of

Her Majesty's Prison Service, Cameron showed him a "his and her list" of proposals made by Howard and his wife,

Sandra. Lewis said that Sandra Howard's list included reducing the quality of

prison food

Prison food is the term for meals served to prisoners while incarcerated in correctional institutions. While some prisons prepare their own food, many use staff from on-site catering companies. Prisoners will typically receive a series of stand ...

, although she denied this claim. Lewis reported that Cameron was "uncomfortable" about the list.

[Leigh, David (23 February 1997). "Mrs Howard's own recipe for prison reform". ''The Observer'' (London).] In defending Sandra Howard and insisting that she made no such proposal, the journalist

Bruce Anderson wrote that Cameron had proposed a much shorter definition on prison catering which revolved around the phrase "balanced diet", and that Lewis had written thanking Cameron for a valuable contribution.

During his work for Howard, Cameron often briefed the media. In March 1994, someone leaked to the press that the Labour Party had called for a meeting with John Major to discuss a consensus on the

Prevention of Terrorism Act. After an inquiry failed to find the source of the leak, Labour MP

Peter Mandelson demanded assurance from Howard that Cameron had not been responsible, which Howard gave.

[ Wintour, Patrick (10 March 1994). "Smith fumes at untraced leak". ''The Guardian'' (London).] A senior

Home Office

The Home Office (HO), also known (especially in official papers and when referred to in Parliament) as the Home Department, is the United Kingdom's interior ministry. It is responsible for public safety and policing, border security, immigr ...

civil servant noted the influence of Howard's Special Advisers, saying previous incumbents "would listen to the evidence before making a decision. Howard just talks to young public school gentlemen from the party headquarters."

Carlton

In July 1994 Cameron left his role as Special Adviser to work as the Director of Corporate Affairs at

Carlton Communications.

["Smallweed". ''The Guardian'' (London). 16 July 1994.] Carlton, which had won the

ITV franchise for London weekdays in 1991, was a growing media company which also had film-distribution and video-producing arms. Cameron was suggested for the role to Carlton executive chairman

Michael P. Green by his later mother-in-law Lady Astor. He left Carlton in 1997 to run for Parliament, returning to his job after his defeat.

In 1997 Cameron played up the company's prospects for

digital terrestrial television

Digital terrestrial television (DTTV, DTT, or DTTB) is a technology for terrestrial television, in which television stations broadcast television content in a digital signal, digital format. Digital terrestrial television is a major technologica ...

, for which it joined with

ITV Granada

ITV Granada, formerly known as Granada Television, is the ITV (TV network), ITV franchisee for the North West of England and Isle of Man. From 1956 to 1968 it broadcast to both the north west and Yorkshire on weekdays only, as ABC Weekend TV, ...

and

Sky

The sky is an unobstructed view upward from the planetary surface, surface of the Earth. It includes the atmosphere of Earth, atmosphere and outer space. It may also be considered a place between the ground and outer space, thus distinct from ...

to form

British Digital Broadcasting. In a roundtable discussion on the future of broadcasting in 1998, he criticised the effect of overlapping different regulators on the industry.

["We can't wait any longer to map the digital mediascape". '']New Statesman

''The New Statesman'' (known from 1931 to 1964 as the ''New Statesman and Nation'') is a British political and cultural news magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first c ...

'' (London). 3 April 1998. Carlton's consortium did win the digital terrestrial franchise, but the resulting company suffered difficulties in attracting subscribers. Cameron resigned as Director of Corporate Affairs in February 2001 to run for Parliament for a second time, although he remained on the payroll as a consultant.

Parliamentary candidacies

Having been approved for the PPCs' list, Cameron began looking for a seat to contest for the

1997 general election. He was reported to have missed out on selection for

Ashford in December 1994, after failing to get to the selection meeting as a result of train delays.

["Pendennis". ''The Observer'' (London). 1 January 1995.] In January 1996, when two shortlisted contenders dropped out, Cameron was interviewed and subsequently selected for

Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, England. It is located about south of Stoke-on-Trent, north of Wolverhampton, and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 71,673 at the 2021–2022 United Kingd ...

, a constituency revised in boundary changes, which was projected to have a Conservative majority.

The incumbent Conservative MP,

Bill Cash, ran instead in the neighbouring constituency of

Stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

, where he was re-elected. At the 1996 Conservative Party Conference, Cameron called for

tax cut

A tax cut typically represents a decrease in the amount of money taken from taxpayers to go towards government revenue. This decreases the revenue of the government and increases the disposable income of taxpayers. Tax rate cuts usually refer ...

s in the forthcoming Budget to be targeted at the low-paid and to "small businesses where people took money out of their own pockets to put into companies to keep them going".

[Sherman, Jill (11 October 1996). "Clarke challenged to show gains of economic recovery". ''The Times'' (London).] He also said the Party "should be proud of the Tory tax record but that people needed reminding of its achievements ... It's time to return to our tax-cutting agenda. The socialist prime ministers of Europe have endorsed Tony Blair because they want a federal pussy cat and not a British lion."

When writing his election address, Cameron made his own opposition to British membership of the

single European currency clear, pledging not to support it. This was a break with official Conservative policy, but about 200 other candidates were making similar declarations.

[Travis, Alan (17 April 1997). "Rebels' seven-year march". ''The Guardian'' (London).] Otherwise, Cameron kept closely to the national

party line. He also campaigned using the claim that a Labour government would increase the cost of a pint of beer by 24p; however, the Labour candidate,

David Kidney, portrayed Cameron as "a right-wing Tory". Initially, Cameron thought he had a 50/50 chance, but as the campaign wore on and the scale of the impending Conservative defeat grew, Cameron prepared himself for defeat. On election day, Stafford had a

swing of 10.7%, almost the same as the national swing, which made it one of the many seats to fall to Labour: Kidney defeated Cameron by 24,606 votes (47.5%) to 20,292 (39.2%), a majority of 4,314 (8.3%).

[Elliott and Hanning (2007), pp. 172–5.]

In the round of selection contests taking place in the run-up to the

2001 general election, Cameron again attempted to be selected for a winnable seat. He tried for the

Kensington and Chelsea seat after the death of

Alan Clark

Alan Kenneth Mackenzie Clark (13 April 1928 – 5 September 1999) was a British Conservative Member of Parliament (MP), author and diarist. He served as a junior minister in Margaret Thatcher's governments at the Departments of Employment, Tr ...

, but did not make the shortlist. He was in the final two but narrowly lost at

Wealden in March 2000,

[White, Michael (14 March 2000). "Rightwingers and locals preferred for safe Tory seats". ''The Guardian'' (London).] a loss ascribed by Samantha Cameron to his lack of spontaneity when speaking.

[Elliott and Hanning (2007), p. 193.]

Cameron was selected as PPC for

Witney

Witney is a market town on the River Windrush in West Oxfordshire in the county of Oxfordshire, England. It is west of Oxford.

History

The Toponymy, place-name "Witney" is derived from the Old English for "Witta's island". The earliest kno ...

in Oxfordshire in April 2000. This had been a safe Conservative seat, but its sitting MP

Shaun Woodward

Shaun Anthony Woodward (born 26 October 1958) is a British politician who served as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland from 2007 to 2010.

A former television researcher and producer, Woodward began his political career in the Conservativ ...

(who had worked with Cameron on the 1992 election campaign) had "crossed the floor" to join the Labour Party, and was selected instead for the safe Labour seat of

St Helens South. Cameron's biographers Francis Elliott and James Hanning describe the two men as being "on fairly friendly terms".

[Elliott and Hanning (2007), p. 192.] Cameron, advised in his strategy by friend

Catherine Fall, put a great deal of effort into "nursing" his potential constituency, turning up at social functions and attacking Woodward for changing his mind on

fox hunting

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase and, if caught, the killing of a fox, normally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds. A group of unarmed followers, led by a "master of foxhounds" (or "master of hounds" ...

to support a ban.

["Why Shaun Woodward changed his mind" (Letter). ''The Daily Telegraph''. 21 December 2000.]

During the election campaign, Cameron accepted the offer of writing a regular column for ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

''s online section.

["The Cameron diaries"](_blank)

(archive). ''The Guardian'' (London). He won the seat with a 1.9% swing to the Conservatives, taking 22,153 votes (45%) to Labour candidate Michael Bartlet's 14,180 (28.8%), a majority of 7,973 (16.2%).

[''Dod's Guide to the General Election June 2001''. (Vacher Dod Publishing, 2001). p. 430.]

Parliamentary backbencher

Upon his election to Parliament, Cameron served as a member of the Commons

Home Affairs Select Committee, a prominent appointment for a newly elected MP. He proposed that the Committee launch an inquiry into the law on drugs,

[Elliott, Francis; Hanning, James (2007). ''Cameron: The Rise of the New Conservative''. London: Fourth Estate. p. 200. ] and urged the consideration of "radical options".

["Examination of Witnesses: question 123"](_blank)

, ''Hansard'', 30 October 2001. Retrieved 4 September 2007. The report recommended a downgrading of

ecstasy from Class A to Class B, as well as moves towards a policy of '

harm reduction

Harm reduction, or harm minimization, refers to a range of intentional practices and public health policies designed to lessen the negative social and/or physical consequences associated with various human behaviors, both legal and illegal. H ...

', which Cameron defended.

["Let's inject reality into the drugs war", ''Edinburgh Evening News'', 22 May 2002]

Cameron endorsed

Iain Duncan Smith

Sir George Iain Duncan Smith (born 9 April 1954), often referred to by his initials IDS, is a British politician who was Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Le ...

in the

2001 Conservative Party leadership election and organised an event in Witney for party supporters to hear

John Bercow speaking for him. Two days before Duncan Smith won the leadership contest on 13 September 2001, the

9/11 attacks occurred. Cameron described Tony Blair's response to the attacks as "masterful", saying: "He moved fast, and set the agenda both at home and abroad. He correctly identified the problem of

Islamist extremism, the inadequacy of our response both domestically and internationally, and supported—quite rightly in my view—the action to

remove the Taliban regime from Afghanistan."

Cameron determinedly attempted to increase his public visibility, offering quotations on matters of public controversy. He opposed the payment of compensation to Gurbux Singh, who had resigned as head of the

Commission for Racial Equality after a confrontation with the police;

[Johnston, Philip; Barrow, Becky (8 August 2002). "£129,000 for race chief in drunken fracas". ''The Daily Telegraph'' (London).] and commented that the Home Affairs Select Committee had taken a long time to discuss whether the phrase "black market" should be used.

["They said what?". ''The Observer'' (London). 30 June 2002.] Cameron was passed over for a front-bench promotion in July 2002. Conservative leader Iain Duncan Smith did invite Cameron and his ally

George Osborne to coach him on Prime Minister's Questions in November 2002. The next week, Cameron deliberately abstained in a vote on allowing same-sex and unmarried couples to adopt children jointly, against a whip to oppose; his abstention was noted.

["Rebels and non-voters". ''The Times'' (London). 6 November 2002.] The wide scale of abstentions and rebellious votes destabilised the Duncan Smith leadership.

Parliamentary frontbencher

In June 2003 Cameron was appointed a

shadow minister in the

Privy Council Office as a deputy to

Eric Forth, then

shadow leader of the House. He also became a vice-

chairman of the Conservative Party

The chairman of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom is responsible for party administration and overseeing the Conservative Campaign Headquarters, formerly Conservative Central Office.

When the Conservative Party (UK), Conservatives are ...

when Michael Howard took over the leadership in November of that year. He was appointed Opposition frontbench

local government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of governance or public administration within a particular sovereign state.

Local governments typically constitute a subdivision of a higher-level political or administrative unit, such a ...

spokesman in 2004, before being promoted to the

Shadow Cabinet that June as

head of policy co-ordination. Later, he became

Shadow Education Secretary in the post-election reshuffle.

Daniel Finkelstein has said of the period leading up to Cameron's election as leader of the Conservative party that "a small group of us (myself, David Cameron, George Osborne,

Michael Gove

Michael Andrew Gove, Baron Gove (; born Graeme Andrew Logan, 26 August 1967) is a British politician and journalist who served in various Cabinet of the United Kingdom, Cabinet positions under David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Rish ...

,

Nick Boles,

Nick Herbert I think, once or twice) used to meet up in the offices of

Policy Exchange, eat pizza, and consider the future of the Conservative Party". Cameron's relationship with Osborne is regarded as particularly close; Conservative MP

Nadhim Zahawi suggested the closeness of Osborne's relationship with Cameron meant the two effectively shared power during Cameron's time as prime minister.

From February 2002 to August 2005, he was a

non-executive director of Urbium PLC, operator of the

Tiger Tiger bar chain.

Term as Leader of the Opposition (2005–2010)

Leadership election

Following the Labour victory in the

May 2005 general election, Michael Howard announced his resignation as leader of the Conservative Party and set a lengthy timetable for the

leadership election. Cameron announced on 29 September 2005 that he would be a candidate. Parliamentary colleagues supporting him included Boris Johnson, shadow chancellor George Osborne, shadow defence secretary and deputy leader of the party

Michael Ancram,

Oliver Letwin

Sir Oliver Letwin (born 19 May 1956) is a British politician, Member of Parliament (MP) for West Dorset from 1997 to 2019. Letwin was elected as a member of the Conservative Party, but sat as an independent after having the whip removed in ...

and former party leader

William Hague

William Jefferson Hague, Baron Hague of Richmond (born 26 March 1961) is a British politician and life peer who was Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition from 1997 to 2001 and Deputy Leader from 2005 to 2010. He was th ...

. His campaign did not gain wide support until his speech, delivered without notes, at the 2005 Conservative

party conference

The terms party conference ( UK English), political convention ( US and Canadian English), and party congress usually refer to a general meeting of a political party. The conference is attended by certain delegates who represent the party memb ...

. In the speech, he vowed to make people "feel good about being Conservatives again" and said he wanted "to switch on a whole new generation". His speech was well-received; ''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' said speaking without notes "showed a sureness and a confidence that is greatly to his credit".

In the first ballot of Conservative MPs on 18 October 2005, Cameron came second, with 56 votes, slightly more than expected;

David Davis had fewer than predicted at 62 votes;

Liam Fox came third with 42 votes; and

Kenneth Clarke

Kenneth Harry Clarke, Baron Clarke of Nottingham (born 2 July 1940) is a British politician who served as Home Secretary from 1992 to 1993 and Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1993 to 1997. A member of the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

was eliminated with 38 votes. In the second ballot on 20 October 2005, Cameron came first with 90 votes; David Davis was second, with 57; and Liam Fox was eliminated with 51 votes. All 198 Conservative MPs voted in both ballots.

The next stage of the election process, between Davis and Cameron, was a vote open to the entire party membership. Cameron was elected with more than twice as many votes as Davis and more than half of all ballots issued; Cameron won 134,446 votes on a 78%

turnout, to Davis's 64,398. Although Davis had initially been the favourite, it was widely acknowledged that his candidacy was marred by a disappointing conference speech. Cameron's election as the leader of the Conservative Party and

leader of the opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

was announced on 6 December 2005. As is customary for an opposition leader not already a member, upon election Cameron became a member of the

Privy Council, being formally approved to join on 14 December 2005, and sworn of the council on 8 March 2006.

Reaction to Cameron as Leader

Cameron's relative youth and inexperience before becoming leader invited satirical comparison with Tony Blair. ''

Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely recognised ...

'' soon published a picture of both leaders on its front cover, with the caption "World's first face transplant a success". On the left, the ''New Statesman'' unfavourably likened his "new style of politics" to Tony Blair's early leadership years.

Cameron was accused of paying excessive attention to appearance:

ITV News

ITV News is the branding of news programmes on the British news television channel of ITV (TV network), ITV. ITV has a long tradition of television news. ITN, Independent Television News (ITN) was founded to provide news bulletins for the netwo ...

broadcast footage from the 2006 Conservative Party Conference in

Bournemouth

Bournemouth ( ) is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area, in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. At the 2021 census, the built-up area had a population of 196,455, making it the largest ...

showing him wearing four different sets of clothes within a few hours.

In his column for ''The Guardian'', comedy writer and broadcaster

Charlie Brooker described the Conservative leader as "a hollow Easter egg with no bag of sweets inside" in April 2007.

On the right of the party,

Norman Tebbit

Norman Beresford Tebbit, Baron Tebbit, (born 29 March 1931) is a British retired politician. A member of the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party, he served in the Cabinet from 1981 to 1987 as Secretary of State for Employment (1981–1 ...

, a former Conservative chairman, likened Cameron to

Pol Pot

Pol Pot (born Saloth Sâr; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian politician, revolutionary, and dictator who ruled the communist state of Democratic Kampuchea from 1976 until Cambodian–Vietnamese War, his overthrow in 1979. During ...

, "intent on purging even the memory of

Thatcherism

Thatcherism is a form of British conservative ideology named after Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher that relates to not just her political platform and particular policies but also her personal character a ...

before building a New Modern Compassionate Green Globally Aware Party".

['']The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'' (London). 4 February 2006, p. 32. Quentin Davies, who defected from the Conservatives to Labour on 26 June 2007, branded him "superficial, unreliable and

ithan apparent lack of any clear convictions" and stated that Cameron had turned the Conservative Party's mission into a "PR agenda".

Traditionalist conservative columnist and author

Peter Hitchens

Peter Jonathan Hitchens (born 1951) is an English Conservatism in the United Kingdom, conservative author, broadcaster, journalist, and commentator. He writes for ''The Mail on Sunday'' and was a Foreign correspondent (journalism), foreign cor ...

wrote: "Mr Cameron has abandoned the last significant difference between his party and the established left", by embracing social liberalism.

[Hitchens, Peter (14 December 2005)]

"The Tories are doomed"

. ''The Guardian'' (London). p. 28. Retrieved 6 November 2006. ''The Daily Telegraph'' correspondent and blogger

Gerald Warner was particularly scathing about Cameron's leadership, saying that it alienated traditionalist conservative elements from the Conservative Party.

Before he became Conservative leader, Cameron was reportedly known to friends and family as "Dave", though his preference is "David" in public.

[Rumbelow, Helen (21 May 2005]

"The gilded youth whose son steeled him in adversity"

''The Times'' (London). Retrieved 4 September 2007. [ Daniel Finkelstein in October 2006 objected to those attempting to belittle Cameron by calling him "Dave". See ] Labour used the slogan

Dave the Chameleon in their

2006 local elections party broadcast to portray Cameron as an ever-changing

populist, which was criticised as

negative campaigning

Negative campaigning is the process of deliberately spreading negative information about someone or something to damage their public image. A colloquial and more derogatory term for the practice is mudslinging.

Deliberate spreading of such in ...

by the Conservative press, including ''The Daily Telegraph'',

though Cameron asserted the broadcast had become his daughter's "favourite video".

[ Rifkind, Hugo (17 May 2006)]

"Well, that worked"

''The Times'' "People" blog. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

Allegations of recreational drug use

During the leadership election, allegations were made that Cameron had used cannabis and

cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

recreationally before becoming an MP. Pressed on this point during the BBC television programme ''

Question Time'', Cameron expressed the view that everybody was allowed to "err and stray" in their past.

During his 2005 Conservative leadership campaign, he addressed the question of drug consumption by remarking: "I did lots of things before I came into politics which I shouldn't have done. We all did."

Shadow Cabinet appointments

His Shadow Cabinet appointments included MPs associated with the various wings of the party. Former leader William Hague was appointed to the foreign affairs brief, while both George Osborne and David Davis were retained, as

shadow chancellor of the Exchequer

The shadow chancellor of the exchequer in the British Parliamentary system is the member of the Official Opposition Shadow Cabinet (United Kingdom), Shadow Cabinet who is responsible for shadowing the Chancellor of the Exchequer, chancellor of ...

and

Shadow Home Secretary

In British politics, the shadow home secretary (formally known as the shadow secretary of state for the home department) is the person within the Official Opposition Shadow Cabinet (UK), shadow cabinet who shadows the home secretary; this effecti ...

, respectively. Hague, assisted by Davis, stood in for Cameron during his

paternity leave in February 2006. In June 2008 Davis announced his intention to

resign as an MP, and was immediately replaced as shadow home secretary by

Dominic Grieve; Davis' surprise move was seen as a challenge to the changes introduced under Cameron's leadership.

A

reshuffle of the Shadow Cabinet was undertaken in January 2009, with the chief change being the appointment of former Chancellor of the Exchequer Kenneth Clarke as Shadow Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Secretary. Cameron stated that "With Ken Clarke's arrival, we now have the best economic team." The reshuffle also saw eight other changes made.

European Conservatives and Reformists

During his successful 2005 campaign to be elected leader of the Conservative Party, Cameron pledged that the Conservative Party's

members of the European Parliament

A member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Comm ...

would leave the

European People's Party

The European People's Party (EPP) is a European political party with Christian democracy, Christian democratic, liberal conservatism, liberal-conservative, and conservative member parties. A transnational organisation, it is composed of other p ...

group, which had a "federalist" approach to the European Union.

[White, Michael; Branigan, Tania (18 October 2005)]

"Clarke battles to avoid Tory wooden spoon".

''The Guardian'' (London). p. 1. Once elected, Cameron began discussions with right-wing and

Eurosceptic parties in other European countries, mainly in eastern Europe; in July 2006, he concluded an agreement to form the

Movement for European Reform

The Movement for European Reform (MER) was a centre-right European political alliance with conservative, pro-free market and Eurosceptic inclinations. It consisted of the Conservative Party of the United Kingdom and the Civic Democratic Par ...

with the Czech

Civic Democratic Party, leading to the formation of a new European Parliament group, the

European Conservatives and Reformists, in 2009 after the

European Parliament elections

Elections to the European Parliament take place every five years by Universal suffrage, universal adult suffrage; with more than 400 million people eligible to vote, they are the second largest democratic elections in the world after Electio ...

.

[Watt, Nicholas (13 July 2006)]

"Cameron to postpone creation of new EU group".

''The Guardian'' (London). p. 14.

Cameron attended a gathering at

Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

's Palladium cinema celebrating the foundation of the alliance.

In forming the caucus, which had 54 MEPs drawn from eight of the 27

EU member states, Cameron reportedly broke with two decades of Conservative co-operation with the centre-right Christian Democrats, the European People's Party (EPP),

on the grounds that they are dominated by European

federalists and supporters of the

Lisbon treaty

The Treaty of Lisbon (initially known as the Reform Treaty) is a European agreement that amends the two Treaty, treaties which form the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU). The Treaty of Lisbon, which was signed by all Member stat ...

.

EPP leader

Wilfried Martens

Wilfried Achiel Emma Martens (; 19 April 1936 – 9 October 2013) was a Belgian politician who served as prime minister of Belgium from 1979 to 1981 and from 1981 to 1992. A member of the Flemish Christian Democratic and Flemish, Christian People ...

, former

prime minister of Belgium

The prime minister of Belgium (; ; ) or the premier of Belgium is the head of the federal government of Belgium, and the most powerful person in Belgian politics.

The first head of government in Belgian history was Henri van der Noot in 179 ...

, stated: "Cameron's campaign has been to take his party back to the centre in every policy area with one major exception: Europe. ... I can't understand his tactics.

Merkel and

Sarkozy will never accept his Euroscepticism."

Shortlists for Parliamentary candidates

Similarly, Cameron's initial "

A-List" of prospective parliamentary candidates was attacked by members of his party,

and the policy was discontinued in favour of

gender

Gender is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender. Although gender often corresponds to sex, a transgender person may identify with a gender other tha ...

-balanced final shortlists. Before being discontinued, the policy had been criticised by senior Conservative MP and former Prisons Spokeswoman

Ann Widdecombe as an "insult to women", and she had accused Cameron of "storing up huge problems for the future".

South Africa

In April 2009 ''

The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'' reported that in 1989, while

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

remained imprisoned under the

apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

regime, Cameron had accepted a trip to South Africa paid for by an anti-sanctions lobby firm. A spokesperson for him responded by saying that the Conservative Party was at that time opposed to

sanctions against South Africa and that his trip was a fact-finding mission. However, the newspaper reported that Cameron's then superior at Conservative Research Department called the trip "jolly", saying that "it was all terribly relaxed, just a little treat, a perk of the job. The

Botha regime was attempting to make itself look less horrible, but I don't regard it as having been of the faintest political consequence." Cameron distanced himself from his party's history of opposing sanctions against the regime. He was criticised by Labour MP

Peter Hain

Peter Gerald Hain, Baron Hain, (born 16 February 1950), is a British politician who served as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland from 2005 to 2007, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions from 2007 to 2008 and twice as Secretary of State ...

, himself an anti-apartheid campaigner.

Raising teaching standards

At the launch of the Conservative Party's education

manifesto

A manifesto is a written declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party, or government. A manifesto can accept a previously published opinion or public consensus, but many prominent ...

in January 2010, Cameron declared an admiration for the "brazenly elite" approach to education of countries such as

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

and

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

, and expressed a desire to "elevate the status of teaching in our country".

He suggested the adoption of more stringent criteria for entry to teaching, and offered repayment of the loans of maths and science graduates obtaining first or 2.1 degrees from "good" universities.

, then president of the

National Union of Students, said: "The message that the Conservatives are sending to the majority of students is that if you didn't go to a university attended by members of the Shadow Cabinet, they don't believe you're worth as much."

Expenses

During the

parliamentary expenses scandal in 2009, Cameron said he would lead Conservatives in repaying "excessive" expenses and threatened to expel MPs that refused, after the expense claims of several members of his shadow cabinet had been questioned:

We have to acknowledge just how bad this is, the public are really angry and we have to start by saying, "Look, this system that we have, that we used, that we operated, that we took part in—it was wrong and we are sorry about that".

A day later ''The Daily Telegraph'' published figures showing over five years he had claimed £82,450 on his second home allowance. Cameron repaid £680 claimed for repairs to his constituency home. Although he was not accused of breaking any rules, Cameron was placed on the defensive over mortgage interest expense claims covering his constituency home, after a report in ''

The Mail on Sunday

''The Mail on Sunday'' is a British conservative newspaper, published in a tabloid format. Founded in 1982 by Lord Rothermere, it is the biggest-selling Sunday newspaper in the UK. Its sister paper, the ''Daily Mail'', was first published i ...

'' suggested he could have reduced the mortgage interest bill by putting an additional £75,000 of his own money towards purchasing the home in Witney, instead of paying off an earlier mortgage on his London home.

Cameron said that doing things differently would not have saved the taxpayer any money, as he was paying more on mortgage interest than he was able to reclaim as expenses anyway.

He also spoke out in favour of laws giving voters the power to "recall" or "sack" MPs accused of wrongdoing.

In April 2014 he was criticised for his handling of the expenses row surrounding Culture Secretary

Maria Miller

Dame Maria Frances Miller'MILLER, Rt Hon. Maria (Frances Lewis)',

Who's Who 2013,

A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc,

2013;

online edn, Oxford University Press, December 2012;

online edn, November 2012

...

, when he rejected calls from fellow Conservative MPs to sack her from the front bench.

2010 general election

The Conservatives had last won a general election in 1992. The

2010 general election resulted in the Conservatives, led by Cameron, winning the largest number of seats (306). This was, however, 20 seats short of an overall majority, and resulted in the nation's first

hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system (typically employing Majoritarian representation, majoritarian electoral systems) to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing ...

since

February 1974.

2010 government formation

Talks between Cameron and then Liberal Democrat leader

Nick Clegg

Sir Nicholas William Peter Clegg (born 7 January 1967) is a British retired politician and media executive who served as Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2015 and as Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2007 to 2015. H ...

led to an agreed Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition. In late 2009 Cameron had urged the Liberal Democrats to join the Conservatives in a new "national movement", saying there was "barely a cigarette paper" between them on a large number of issues. The invitation was rejected at the time by Clegg who said that the Conservatives were totally different from his party, and that the Lib Dems were the true "progressives" in UK politics.

Premiership (2010–2016)

Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

, following Gordon Brown's resignation as prime minister on 11 May 2010, extended an invitation to Cameron to establish a new administration based on Brown's recommendation.

At age 43, Cameron became the youngest prime minister since

Lord Liverpool

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. Before becoming Prime Minister he had been Foreign Secretary, ...

in 1812, beating the record previously set by Tony Blair in May 1997.

In his first address outside

10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London is the official residence and office of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. Colloquially known as Number 10, the building is located in Downing Street, off Whitehall in th ...

, he announced his intention to form a

coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

, the first since the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, with the Liberal Democrats.

Cameron outlined how he intended to "put aside party differences and work hard for the common good and for the national interest".

As one of his first moves Cameron appointed Nick Clegg, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, as deputy prime minister on 11 May 2010.

Between them, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats controlled 363 seats in the House of Commons, giving them a comfortable majority of 76 seats.In June 2010, Cameron described the economic situation as he came to power as "even worse than we thought" and warned of "difficult decisions" to be made over spending cuts. By the beginning of 2015, he was able to claim that

his government's austerity programme had succeeded in halving the

budget deficit

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit, the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budg ...

, although as a percentage of

GDP rather than in cash terms.

In December 2010, Cameron attended a meeting with

FIFA

The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (), more commonly known by its acronym FIFA ( ), is the international self-regulatory governing body of association football, beach soccer, and futsal. It was founded on 21 May 1904 to o ...

vice-president

Chung Mong-joon, in which a vote-trading deal for the right to host the 2018 World Cup in England was discussed.

Cameron agreed to holding the

2014 Scottish independence referendum

A independence referendum, referendum on Scottish independence from the United Kingdom was held in Scotland on 18 September 2014. The referendum question was "Should Scotland be an independent country?", which voters answered with "Yes" or ...

and eliminated the "

devomax" option from the ballot for a straight out yes or no vote. His support for the successful