David Bruce (microbiologist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Major-General Sir David Bruce, (29 May 1855 – 27 November 1931) was a Scottish

/ref> He was immediately appointed chairman of the governing body of the Lister Institute. During his career, he published more than ninety-seven technical articles, of which about thirty were co-authored by his wife.

File:David Bruce (microbiologist) 2.jpg

File:David Bruce (microbiologist).jpg, Bruce on the porch of his hut in Ubombo, Zululand (now South Africa), where he discovered ''Trypanosoma brucei''.

File:David Bruce (microbiologist) and wife.jpg, Bruce with wife

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine biographical article

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bruce, David 19th-century Scottish inventors 19th-century Scottish biologists Scottish microbiologists Scottish pathologists People educated at Stirling High School Alumni of the University of Edinburgh 1855 births 1931 deaths Royal Medal winners Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Leeuwenhoek Medal winners Manson medal winners Royal Army Medical Corps officers British Army personnel of the Second Boer War British Army generals of World War I Presidents of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene People from the Colony of Victoria

pathologist

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

and microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, fungi, and some types of par ...

who made some of the key contributions in tropical medicine

Tropical medicine is an interdisciplinary branch of medicine that deals with health issues that occur uniquely, are more widespread, or are more difficult to control in tropical and subtropical regions.

Physicians in this field diagnose and tr ...

. In 1887, he discovered a bacterium, now called ''Brucella

''Brucella'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacterium, bacteria, named after David Bruce (microbiologist), David Bruce (1855–1931). They are small (0.5 to 0.7 by 0.6 to 1.5 μm), non-Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, non-motile, facultatively ...

'', that caused what was known as Malta fever. In 1894, he discovered a protozoan parasite, named ''Trypanosoma brucei

''Trypanosoma brucei'' is a species of parasitic Kinetoplastida, kinetoplastid belonging to the genus ''Trypanosoma'' that is present in sub-Saharan Africa. Unlike other protozoan parasites that normally infect blood and tissue cells, it is excl ...

'', as the causative pathogen of nagana (animal trypanosomiasis

Animal trypanosomiasis, also known as nagana and nagana pest, or sleeping sickness, is a disease of non-human vertebrates. The disease is caused by trypanosoma, trypanosomes of several species in the genus ''Trypanosoma'' such as ''Trypanosoma ...

).

Working in the Army Medical Services

The Army Medical Services (AMS) is the organisation responsible for administering the corps that deliver medical, veterinary, dental and nursing services in the British Army. It is headquartered at the former Staff College, Camberley, near the ...

and the Royal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) was a specialist corps in the British Army which provided medical services to all Army personnel and their families, in war and in peace.

On 15 November 2024, the corps was amalgamated with the Royal Army De ...

, Bruce's major scientific collaborator was his microbiologist wife Mary Elizabeth Bruce (''née'' Steele), with whom he published around thirty technical papers out of his 172 papers. In 1886, he was chairman of the Malta Fever Commission that investigated the deadly disease, by which he identified a specific bacterium as the cause. Later, with his wife, he investigated an outbreak of animal disease called nagana in Zululand and discovered the protozoan parasite responsible for it. He led the second and third Sleeping Sickness Commission organised by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

that investigated an epidemic of human sleeping sickness in Uganda, where he established that tsetse fly was the carrier (vector

Vector most often refers to:

* Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

* Disease vector, an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematics a ...

) of these human and animal diseases.

The bacterium, ''Brucella'', and the disease it caused, brucellosis

Brucellosis is a zoonosis spread primarily via ingestion of raw milk, unpasteurized milk from infected animals. It is also known as undulant fever, Malta fever, and Mediterranean fever.

The bacteria causing this disease, ''Brucella'', are small ...

, along with the protozoan ''Trypanosoma brucei

''Trypanosoma brucei'' is a species of parasitic Kinetoplastida, kinetoplastid belonging to the genus ''Trypanosoma'' that is present in sub-Saharan Africa. Unlike other protozoan parasites that normally infect blood and tissue cells, it is excl ...

'', are named in his honour.

Early life and education

Bruce was born inMelbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

, Colony of Victoria

The Colony of Victoria was a historical administrative division in Australia that existed from 1851 until 1901, when it federated with other colonies to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Situated in the southeastern corner of the Australian ...

, to Scottish parents, engineer David Bruce (from Airth

Airth () is a Royal Burgh, village, former trading port and civil parish in Falkirk, Scotland. It is north of Falkirk town and sits on the banks of the River Forth. Airth lies on the A905 road between Grangemouth and Stirling and is overlooked ...

) and his wife Jane Russell Hamilton (from Stirling

Stirling (; ; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Central Belt, central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town#Scotland, market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the roya ...

), who had emigrated to Australia in the gold rush of 1850. He returned with his family to Scotland at the age of five. They lived at 1 Victoria Square in Stirling. He was educated at Stirling High School

Stirling High School is a state high school for 11- to 18-year-olds run by Stirling Council in Stirling, Scotland. It is one of seven high school#Scotland, high schools in the Stirling district, and has approximately 972 pupils. It is located ...

and in 1869 began an apprenticeship in Manchester. However, a bout of pneumonia forced him to abandon this and re-assess his career. He then decided to study zoology but later changed to medicine at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

in 1876. He graduated in 1881.

Medical career

After a brief period as a general practitioner inReigate

Reigate ( ) is a town status in the United Kingdom, town in Surrey, England, around south of central London. The settlement is recorded in Domesday Book of 1086 as ''Cherchefelle'', and first appears with its modern name in the 1190s. The ea ...

, Surrey (1881–83), where he met and married his wife Mary, he entered the Army Medical School in Hampshire at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley. He passed the military examination in 1883 and joined the Army Medical Services

The Army Medical Services (AMS) is the organisation responsible for administering the corps that deliver medical, veterinary, dental and nursing services in the British Army. It is headquartered at the former Staff College, Camberley, near the ...

(in which he served until 1919). For his first post he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) was a specialist corps in the British Army which provided medical services to all Army personnel and their families, in war and in peace.

On 15 November 2024, the corps was amalgamated with the Royal Army De ...

in 1884 and was stationed in Valletta

Valletta ( ; , ) is the capital city of Malta and one of its 68 Local councils of Malta, council areas. Located between the Grand Harbour to the east and Marsamxett Harbour to the west, its population as of 2021 was 5,157. As Malta’s capital ...

, Malta.

Bruce was appointed assistant professor of pathology at the Army Medical School in Netley in 1889, and served there for five years. He returned to military field service in 1894 and was posted to Pietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; ) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa after Durban. It was named in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. The town was named in Zulu after King ...

, Natal, South Africa. He was assigned to investigate the case of cattle and horse sickness (called nagana) in Zululand. On 27 October 1894, he and his wife (Mary Elizabeth) moved to Ubombo Hill, where the disease was most prevalent. When the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

broke out in 1899, accompanied by his wife, he ran the field hospital during the Siege of Ladysmith (2 November 1899 until 28 February 1900). For his service during the war, he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel. In 1899, Bruce was awarded the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh

The Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh is awarded by the University of Edinburgh College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine to a person who has made any highly important and v ...

. In 1900, he joined the army commission investigating dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

in military camps, at the same time working for the Royal Society's Sleeping Sickness Commission.

Bruce served as a member of the Army Medical Service Advisory Board from 1902 to 1911. In 1914 he became Commander of the Royal Army Medical College at Millbank, London, the position he held until his retirement as a Major-General in 1919.S R Christophers: 'Bruce, Sir David (1855–1931)' (rev. Helen J Power), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2008, accessed 23 May 2014/ref> He was immediately appointed chairman of the governing body of the Lister Institute. During his career, he published more than ninety-seven technical articles, of which about thirty were co-authored by his wife.

Death

He died four days after his wife in 1931, during her memorial service. Both were cremated in London and their ashes are buried together in Valley Cemetery in Stirling, close toStirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most historically and architecturally important castles in Scotland. The castle sits atop an Intrusive rock, intrusive Crag and tail, crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill ge ...

, beneath a simple stone cross on the east side of the main north-south path, near the southern roundel. They had no children.

Scientific contributions

Malta fever

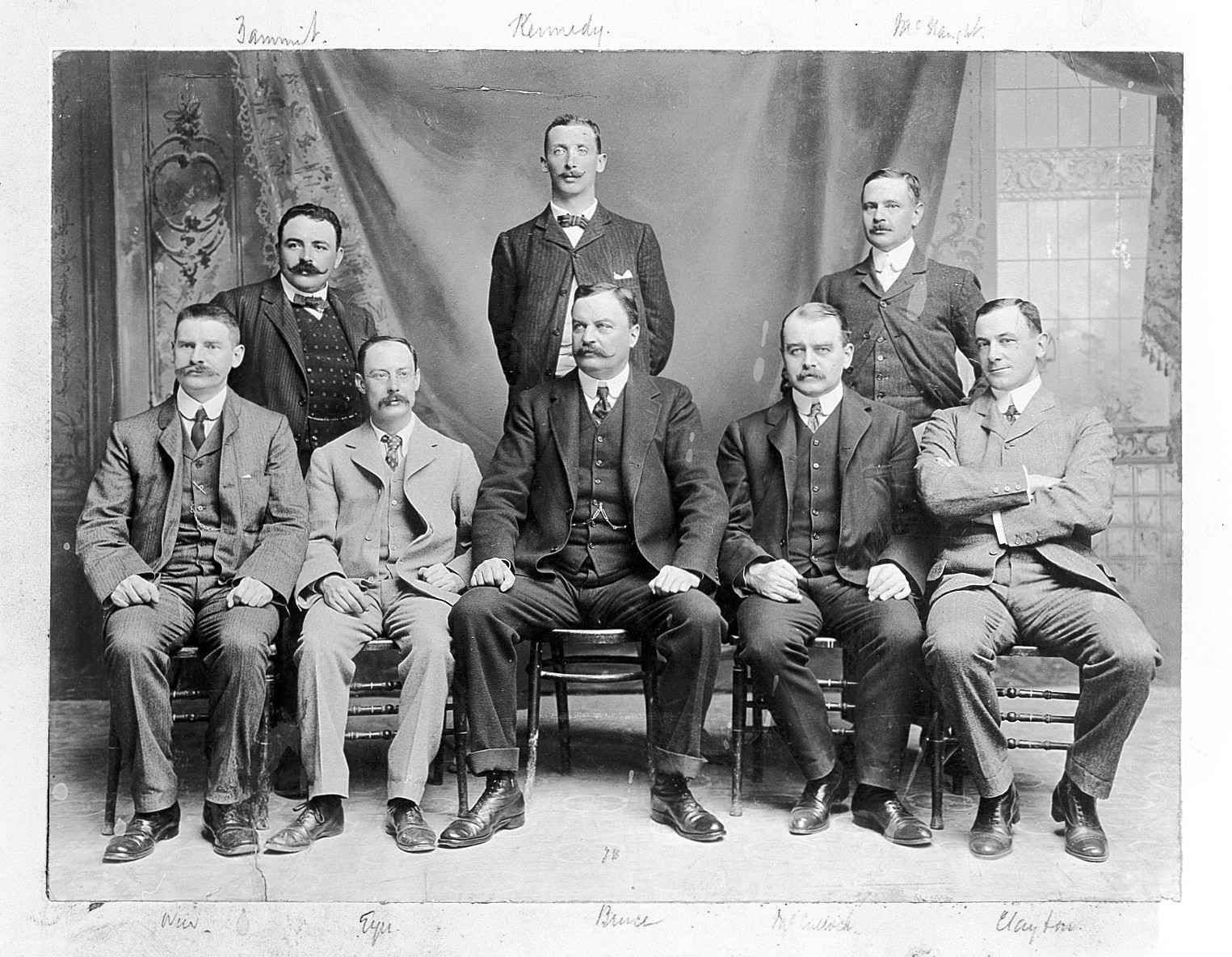

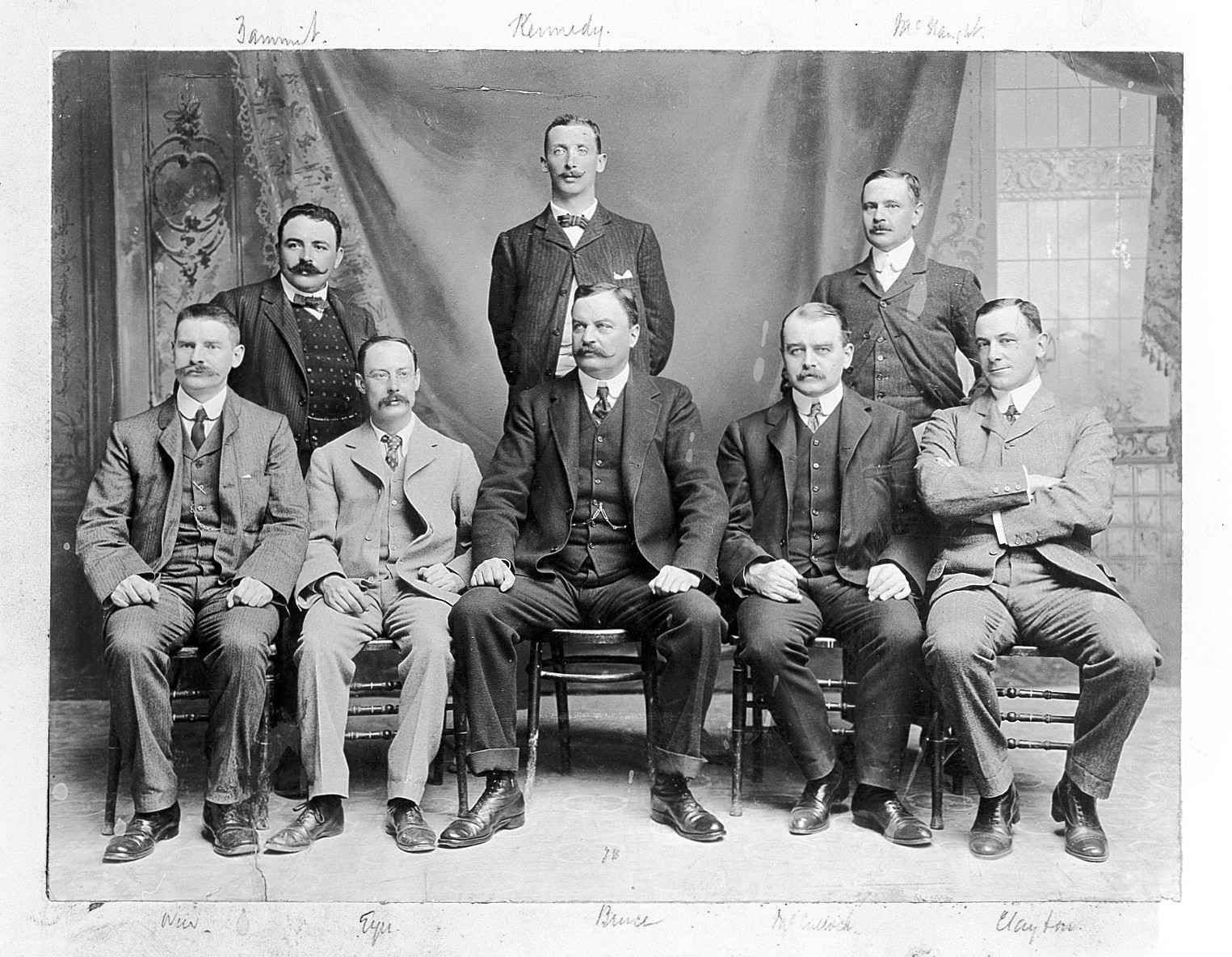

At the time of Bruce's service in Malta, British soldiers suffered an outbreak of what was called the Malta fever. The disease caused undulant fever in men and abortion in goats. It is transmitted by goat milk. In 1886, Bruce led the Malta Fever Commission that investigated the epidemic. Between 1886 and 1887, he studied five patients having Malta fever who died of the disease. From the spleen of corpses, he recovered a bacterium which he referred to as ''Micrococcus,'' which he described:When a minute portion taken from one of these ulturecolonies is placed in a drop of sterilized water and examined under a high power f microscope innumerable small micrococci are seen. They are very active and dance about—as a rule singly, sometimes in pairs, rarely in short chains.Bruce's assistant, Surgeon Captain Matthew Louis Hughes named the disease "undulant fever" and the bacterium, ''Micrococcus melitensis.'' The source of the infection was not clear, Hughes believing it to come from the soil and the bacterium inhaled from the air. Bruce reported the discovery in '' The Practitioner'' in 1887 with the conclusion:

I think it will appear to be sufficiently proved: (a) that there exists in the spleen of cases of Malta fever a definite micro-organism; and (b) that this micro-organism can be cultivated outside the human body. On the latter point, I may remark that I have already cultivated four successive generations. It now remains to be seen what effect, if any, this micro-organism has on healthy animals; what are the conditions of temperature, &c., under which it flourishes; where it is to be found; how it gains entrance to its human host; and many other points. All of these will take a long time to investigate. I have therefore published this preliminary note in order to draw the attention of other workers to what seems to me to be an attractive field.He was correct in his prediction that it was only in 1905 that goat milk was established as the source of the infection. The discovery that the disease was transmitted from goat milk was generally attributed to Bruce himself. But an analysis of the historical record in 2005 revealed that Themistocles Zammit, one of the members of the commission, was the one who experimentally demonstrated the origin of the bacterium from goat milk. The genus ''Micrococcus'' was changed to ''

Brucella

''Brucella'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacterium, bacteria, named after David Bruce (microbiologist), David Bruce (1855–1931). They are small (0.5 to 0.7 by 0.6 to 1.5 μm), non-Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, non-motile, facultatively ...

'' in honour of Bruce and is accepted as a valid name. Accordingly, the disease has been renamed brucellosis

Brucellosis is a zoonosis spread primarily via ingestion of raw milk, unpasteurized milk from infected animals. It is also known as undulant fever, Malta fever, and Mediterranean fever.

The bacteria causing this disease, ''Brucella'', are small ...

.

Fly disease and sleeping sickness

When Bruce was transferred to South Africa, he was sent to Zululand to investigate the outbreak of animal disease which the natives called '' nagana,'' and the Europeans, the fly disease. In 1894, he and his wife found that the disease was prevalent among cattle, donkeys, horses, and dogs. They collected blood samples from such infected animals and found parasites which Bruce identified correctly as a type of "Haematozoon" (attributed to protozoans that are blood parasites), as he described in his report in 1895:At this point, I think it will be convenient to give a definite description of the parasite discovered by me in the blood of animals affected by this disease and to bring forward my reasons for considering it to be the proximate exciting cause of the disease. For the present I shall call it the Haematozoon or Blood Parasite of Fly disease, although in all probability on further knowledge, it will be found to be identical with the haematozoon of Surra, which is called '' Trypanosoma Evansi'' or at least a species belonging to that genus...He also made accurate identification characters of the parasite as unique organisms:

nder a microscopecan be seen transparent elongated bodies in active movement, wriggling about like tiny snakes and swimming from corpuscle to corpuscle, which they seem to seize upon and worry. They appear to be about a quarter of the diameter of a Red Blood Corpuscle in thickness, and 2 or 3 times the diameter of a corpuscle in length. They are pointed or somewhat blunt at one end, and the other extremity is seen to be prolonged into a very fine lash, which is in constant whip-like motion. Running along the cylindrical body between the two extremities can be seen a transparent delicate longitudinal membrane or fin ater named undulating membranewhich is also constantly in wave-like motion... These parasites evidently belong to a very low form of animal life, namely theHe performed several experiments on different animals as to how the parasite was transmitted. He found that the tsetse fly ('' Glossina morsitans''), which was common in the region, could carry the live parasites from feeding on the blood of the animals. He established that "the Tsetse Fly plays a most important part in the propagation of the disease", but was unable to show that the flies could actually transmit the disease. He explained:infusoria Infusoria is a word used to describe various freshwater microorganisms, including ciliates, copepods, Euglena, euglenoids, planktonic crustaceans, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates. Some authors (e.g., Otto Bütschli, Bütschli) ..., and simply consist of a small mass of protoplasm surrounded by a limiting membrane, and without any differentiation of structure, except in so far as the membrane is prolonged to form the longitudinal fin and flagellum.

I have not been able exactly to prove the part which the Tsetse Fly plays in the causation or production of the Fly Disease, I think it well to begin with a consideration of the Fly itself, not only on account of its historical value, but also because I am at present of opinion that the Tsetse Fly does play some part, and perhaps no inconsiderable part, in the propagation of the disease. Be it at once stated that I have not the slightest belief in the notion popularly prevalent up to the present that the Fly causes the disease by the injection of a poison elaborated by itself, after the manner of the leech, which injects a fluid to prevent the coagulation of the blood, or the snake for the purpose of procuring its prey or for defence, but that at most the Tsetse acts as a carrier of a living virus, an infinitely small parasite, from one animal to another, which entering into the bloodstream of the animal bitten or pricked, there propagates and so gives rise to the disease.Henry George Plimmer and John Rose Bradford gave the full description of the new parasite in 1899 as ''Trypanosoma brucei'', the name after the discoverer.

Sleeping Sickness Commission

There was an outbreak of sleeping sickness in Uganda from 1900. By 1901, it became severe with death toll estimated to about 20,000. More than 250,000 people died in the epidemic that lasted for two decades. The disease commonly popularised as "negro lethargy" was not known to be related to the fly disease. At the time, the human disease was believed to be either a bacterial infection or helminth infection. The Royal Society constituted a three-member Sleeping Sickness Commission in 1902 to investigate the epidemic. Led by George Carmichael Low from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the team included his colleague Aldo Castellani and Cuthbert Christy, a medical officer on duty in Bombay, India. The expedition was a failure as they found that bacteria or helminths were not involved in the disease. The second Commission in 1902 was entrusted to Bruce, assisted by David Nunes Nabarro from theUniversity College Hospital

University College Hospital (UCH) is a teaching hospital in the Fitzrovia area of the London Borough of Camden, England. The hospital, which was founded as the North London Hospital in 1834, is closely associated with University College Lo ...

. By August 1903, Bruce and his team established that the disease was transmitted by the tsetse fly, ''Glossina palpalis.'' The relationship with the fly disease in animals became obvious. In the third Commission (1908–1912) Bruce and his colleagues established the complete developmental stages of the trypanosome in tsetse fly''.''

Honours and awards

Bruce was elected a Fellow of theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

(FRS) in 1899. He served as editor of the '' Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps'' between 1904 and 1908. He was the recipient of the Cameron Prize from Edinburgh University in 1901. He received the Royal Society's Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal and The King's Medal (depending on the gender of the monarch at the time of the award), is a silver-gilt medal, of which three are awarded each year by the Royal Society. Two are given for "the mo ...

in 1904, the Mary Kingsley Medal in 1905, and the Stewart Prize of the British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union and professional body for physician, doctors in the United Kingdom. It does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The BMA ...

. He was Croonian lecturer at the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to simply as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of ph ...

in 1915. He was awarded the Leeuwenhoek Medal in 1915, created a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregi ...

(CB) in the 1905 Birthday Honours, knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in 1908 and upgraded to a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(KCB) in 1918. He was president of the British Science Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

during 1924–1925.

Bruce's name features on the frieze

In classical architecture, the frieze is the wide central section of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic order, Ionic or Corinthian order, Corinthian orders, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Patera (architecture), Paterae are also ...

of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a member institution of the University of London that specialises in public health and tropical medicine. The institu ...

. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building on Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.

Bruce was nominated 31 times for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

between 1904 and 1932 for his discoveries in trypanosomiasis but was never selected.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine biographical article

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bruce, David 19th-century Scottish inventors 19th-century Scottish biologists Scottish microbiologists Scottish pathologists People educated at Stirling High School Alumni of the University of Edinburgh 1855 births 1931 deaths Royal Medal winners Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Leeuwenhoek Medal winners Manson medal winners Royal Army Medical Corps officers British Army personnel of the Second Boer War British Army generals of World War I Presidents of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene People from the Colony of Victoria