Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a

polymer

A polymer () is a chemical substance, substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeat unit, repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their br ...

composed of two

polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a

double helix

In molecular biology, the term double helix refers to the structure formed by base pair, double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double Helix, helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its Nuclei ...

. The polymer carries

genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and

reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. There are two forms of reproduction: Asexual reproduction, asexual and Sexual ...

of all known

organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s and many

virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es. DNA and

ribonucleic acid

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins ( messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyr ...

(RNA) are

nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s. Alongside

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s,

lipids

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins Vitamin A, A, Vitamin D, D, Vitamin E, E and Vitamin K, K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The fu ...

and complex carbohydrates (

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s), nucleic acids are one of the four major types of

macromolecule

A macromolecule is a "molecule of high relative molecular mass, the structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass." Polymers are physi ...

s that are essential for all known forms of

life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

.

The two DNA strands are known as polynucleotides as they are composed of simpler

monomer

A monomer ( ; ''mono-'', "one" + '' -mer'', "part") is a molecule that can react together with other monomer molecules to form a larger polymer chain or two- or three-dimensional network in a process called polymerization.

Classification

Chemis ...

ic units called

nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s. Each nucleotide is composed of one of four

nitrogen-containing nucleobase

Nucleotide bases (also nucleobases, nitrogenous bases) are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nuc ...

s (

cytosine

Cytosine () (symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleotide bases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attac ...

guanine

Guanine () (symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleotide bases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside ...

adenine

Adenine (, ) (nucleoside#List of nucleosides and corresponding nucleobases, symbol A or Ade) is a purine nucleotide base that is found in DNA, RNA, and Adenosine triphosphate, ATP. Usually a white crystalline subtance. The shape of adenine is ...

or

thymine

Thymine () (symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleotide bases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine ...

, a

sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

called

deoxyribose, and a

phosphate group

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosp ...

. The nucleotides are joined to one another in a chain by

covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

s (known as the

phosphodiester linkage) between the sugar of one nucleotide and the phosphate of the next, resulting in an alternating

sugar-phosphate backbone. The nitrogenous bases of the two separate polynucleotide strands are bound together, according to

base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

ing rules (A with T and C with G), with

hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s to make double-stranded DNA. The complementary nitrogenous bases are divided into two groups, the single-ringed

pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The oth ...

s and the double-ringed

purines. In DNA, the pyrimidines are thymine and cytosine; the purines are adenine and guanine.

Both strands of double-stranded DNA store the same

biological information. This information is

replicated when the two strands separate. A large part of DNA (more than 98% for humans) is

non-coding, meaning that these sections do not serve as patterns for

protein sequences. The two strands of DNA run in opposite directions to each other and are thus

antiparallel. Attached to each sugar is one of four types of nucleobases (or ''bases''). It is the

sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is cal ...

of these four nucleobases along the backbone that encodes genetic information. RNA strands are created using DNA strands as a template in a process called

transcription, where DNA bases are exchanged for their corresponding bases except in the case of thymine (T), for which RNA substitutes

uracil

Uracil () (nucleoside#List of nucleosides and corresponding nucleobases, symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleotide bases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via ...

(U). Under the

genetic code

Genetic code is a set of rules used by living cell (biology), cells to Translation (biology), translate information encoded within genetic material (DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished ...

, these RNA strands specify the sequence of

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s within proteins in a process called

translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

.

Within eukaryotic cells, DNA is organized into long structures called

chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

s. Before typical

cell division, these chromosomes are duplicated in the process of DNA replication, providing a complete set of chromosomes for each daughter cell.

Eukaryotic organisms (

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s,

plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s,

fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

and

protist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

s) store most of their DNA inside the

cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (; : nuclei) is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have #Anucleated_cells, ...

as

nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. ...

, and some in the

mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

as

mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

or in

chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

s as

chloroplast DNA. In contrast,

prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s (

bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and

archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

) store their DNA only in the

cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

, in

circular chromosomes. Within eukaryotic chromosomes,

chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important r ...

proteins, such as

histones, compact and organize DNA. These compacting structures guide the interactions between DNA and other proteins, helping control which parts of the DNA are transcribed.

Properties

DNA is a long

polymer

A polymer () is a chemical substance, substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeat unit, repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their br ...

made from repeating units called

nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s.

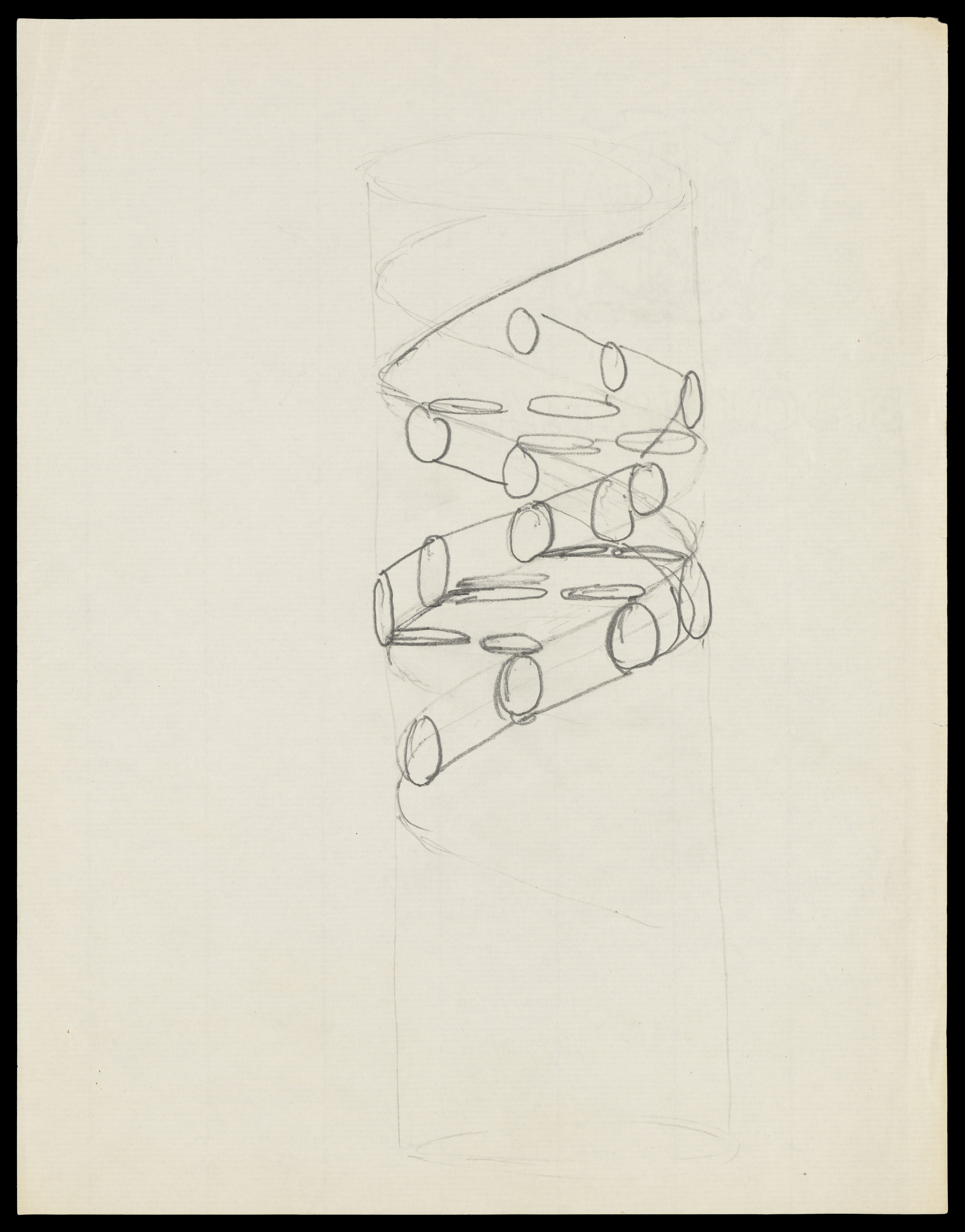

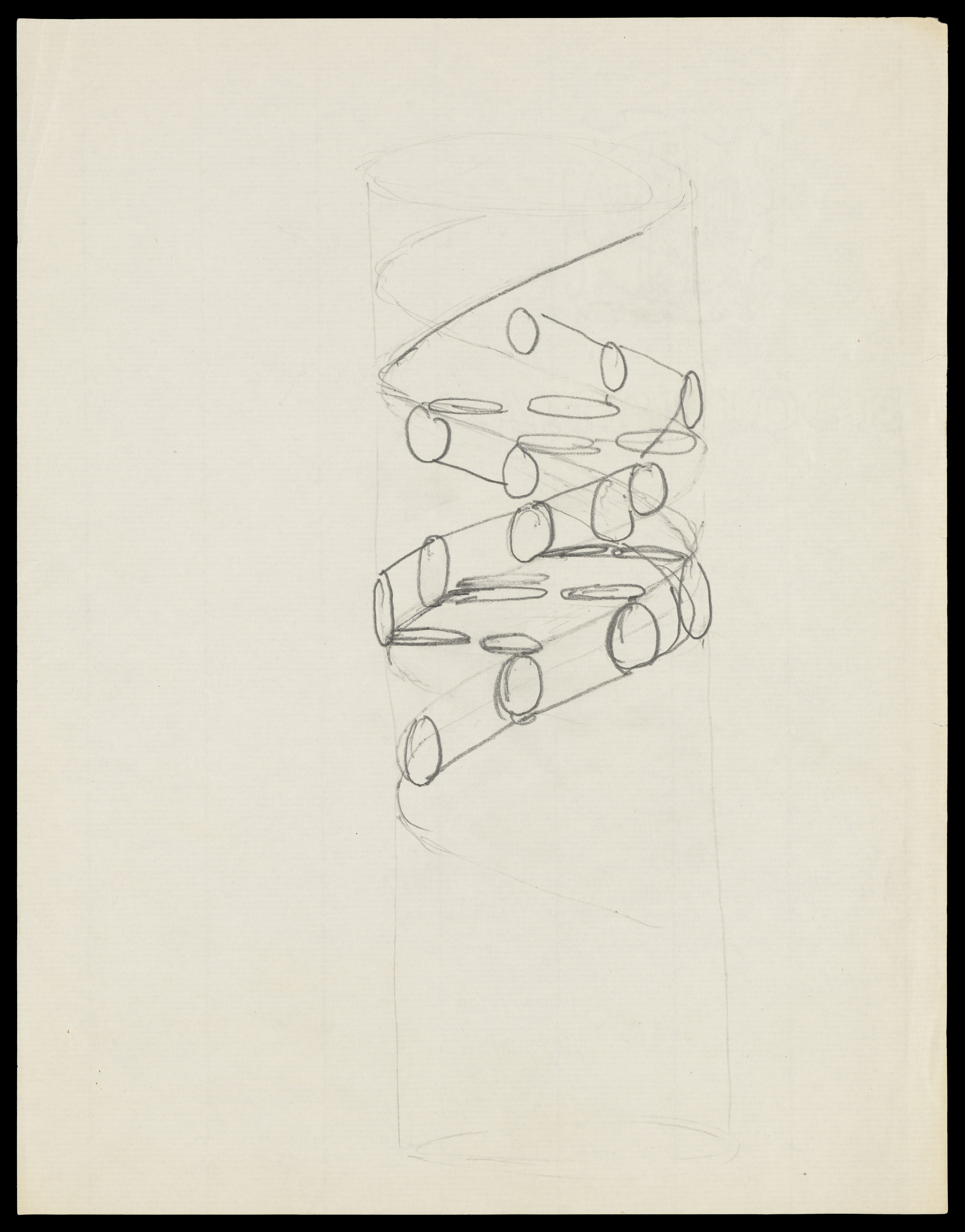

The structure of DNA is dynamic along its length, being capable of coiling into tight loops and other shapes. In all species it is composed of two helical chains, bound to each other by

hydrogen bonds. Both chains are coiled around the same axis, and have the same

pitch of . The pair of chains have a radius of .

According to another study, when measured in a different solution, the DNA chain measured wide, and one nucleotide unit measured long. The buoyant density of most DNA is 1.7g/cm

3.

DNA does not usually exist as a single strand, but instead as a pair of strands that are held tightly together.

These two long strands coil around each other, in the shape of a

double helix

In molecular biology, the term double helix refers to the structure formed by base pair, double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double Helix, helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its Nuclei ...

. The nucleotide contains both a segment of the

backbone of the molecule (which holds the chain together) and a

nucleobase

Nucleotide bases (also nucleobases, nitrogenous bases) are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nuc ...

(which interacts with the other DNA strand in the helix). A nucleobase linked to a sugar is called a

nucleoside, and a base linked to a sugar and to one or more phosphate groups is called a

nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

. A

biopolymer

Biopolymers are natural polymers produced by the cells of living organisms. Like other polymers, biopolymers consist of monomeric units that are covalently bonded in chains to form larger molecules. There are three main classes of biopolymers, ...

comprising multiple linked nucleotides (as in DNA) is called a

polynucleotide.

The backbone of the DNA strand is made from alternating

phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

and

sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

groups.

The sugar in DNA is

2-deoxyribose, which is a

pentose (five-

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

) sugar. The sugars are joined by phosphate groups that form

phosphodiester bond

In chemistry, a phosphodiester bond occurs when exactly two of the hydroxyl groups () in phosphoric acid react with hydroxyl groups on other molecules to form two ester bonds. The "bond" involves this linkage . Discussion of phosphodiesters is d ...

s between the third and fifth carbon

atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

s of adjacent sugar rings. These are known as the

3′-end (three prime end), and

5′-end (five prime end) carbons, the prime symbol being used to distinguish these carbon atoms from those of the base to which the deoxyribose forms a

glycosidic bond.

Therefore, any DNA strand normally has one end at which there is a phosphate group attached to the 5′ carbon of a ribose (the 5′ phosphoryl) and another end at which there is a free hydroxyl group attached to the 3′ carbon of a ribose (the 3′ hydroxyl). The orientation of the 3′ and 5′ carbons along the sugar-phosphate backbone confers

directionality (sometimes called polarity) to each DNA strand. In a

nucleic acid double helix

In molecular biology, the term double helix refers to the structure formed by double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its secondary structure, a ...

, the direction of the nucleotides in one strand is opposite to their direction in the other strand: the strands are

antiparallel. The asymmetric ends of DNA strands are said to have a directionality of five prime end (5′ ), and three prime end (3′), with the 5′ end having a terminal phosphate group and the 3′ end a terminal hydroxyl group. One major difference between DNA and

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

is the sugar, with the 2-deoxyribose in DNA being replaced by the related pentose sugar

ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this comp ...

in RNA.

The DNA double helix is stabilized primarily by two forces:

hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s between nucleotides and

base-stacking interactions among

aromatic

In organic chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property describing the way in which a conjugated system, conjugated ring of unsaturated bonds, lone pairs, or empty orbitals exhibits a stabilization stronger than would be expected from conjugati ...

nucleobases.

The four bases found in DNA are

adenine

Adenine (, ) (nucleoside#List of nucleosides and corresponding nucleobases, symbol A or Ade) is a purine nucleotide base that is found in DNA, RNA, and Adenosine triphosphate, ATP. Usually a white crystalline subtance. The shape of adenine is ...

(),

cytosine

Cytosine () (symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleotide bases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attac ...

(),

guanine

Guanine () (symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleotide bases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside ...

() and

thymine

Thymine () (symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleotide bases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine ...

(). These four bases are attached to the sugar-phosphate to form the complete nucleotide, as shown for

adenosine monophosphate

Adenosine monophosphate (AMP), also known as 5'-adenylic acid, is a nucleotide. AMP consists of a phosphate group, the sugar ribose, and the nucleobase adenine. It is an ester of phosphoric acid and the nucleoside adenosine. As a substituent it t ...

. Adenine pairs with thymine and guanine pairs with cytosine, forming and

base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s.

Nucleobase classification

The nucleobases are classified into two types: the

purines, and , which are fused five- and six-membered

heterocyclic compounds, and the

pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The oth ...

s, the six-membered rings and .

A fifth pyrimidine nucleobase,

uracil

Uracil () (nucleoside#List of nucleosides and corresponding nucleobases, symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleotide bases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via ...

(), usually takes the place of thymine in RNA and differs from thymine by lacking a

methyl group

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula (whereas normal methane has the formula ). In formulas, the group is often abbreviated a ...

on its ring. In addition to RNA and DNA, many artificial

nucleic acid analogues have been created to study the properties of nucleic acids, or for use in biotechnology.

Non-canonical bases

Modified bases occur in DNA. The first of these recognized was

5-methylcytosine, which was found in the

genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

of ''

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis.

First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' ha ...

'' in 1925.

The reason for the presence of these noncanonical bases in bacterial viruses (

bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

s) is to avoid the

restriction enzyme

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or'' restrictase '' is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class o ...

s present in bacteria. This enzyme system acts at least in part as a molecular immune system protecting bacteria from infection by viruses.

Modifications of the bases cytosine and adenine, the more common and modified DNA bases, play vital roles in the

epigenetic control of gene expression in plants and animals.

A number of noncanonical bases are known to occur in DNA.

Most of these are modifications of the canonical bases plus uracil.

* Modified Adenine

** N6-carbamoyl-methyladenine

** N6-methyadenine

* Modified Guanine

** 7-Deazaguanine

** 7-Methylguanine

* Modified Cytosine

** N4-Methylcytosine

** 5-Carboxylcytosine

** 5-Formylcytosine

** 5-Glycosylhydroxymethylcytosine

** 5-Hydroxycytosine

** 5-Methylcytosine

* Modified Thymidine

** α-Glutamythymidine

** α-Putrescinylthymine

* Uracil and modifications

**

Base J

β-D-Glucopyranosyloxymethyluracil or base J is a hypermodified nucleobase found in the DNA of kinetoplastids including the human Pathogen, pathogenic trypanosomes. It was discovered in 1993, in the trypanosome ''Trypanosoma brucei'' and was the f ...

** Uracil

** 5-Dihydroxypentauracil

** 5-Hydroxymethyldeoxyuracil

* Others

** Deoxyarchaeosine

** 2,6-Diaminopurine (2-Aminoadenine)

Grooves

Twin helical strands form the DNA backbone. Another double helix may be found tracing the spaces, or grooves, between the strands. These voids are adjacent to the base pairs and may provide a

binding site

In biochemistry and molecular biology, a binding site is a region on a macromolecule such as a protein that binds to another molecule with specificity. The binding partner of the macromolecule is often referred to as a ligand. Ligands may includ ...

. As the strands are not symmetrically located with respect to each other, the grooves are unequally sized. The major groove is wide, while the minor groove is in width. Due to the larger width of the major groove, the edges of the bases are more accessible in the major groove than in the minor groove. As a result, proteins such as

transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription (genetics), transcription of genetics, genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding t ...

s that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contact with the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove.

This situation varies in unusual conformations of DNA within the cell ''(see below)'', but the major and minor grooves are always named to reflect the differences in width that would be seen if the DNA was twisted back into the ordinary

B form.

Base pairing

Top, a base pair with three

hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s. Bottom, an base pair with two hydrogen bonds. Non-covalent hydrogen bonds between the pairs are shown as dashed lines.

In a DNA double helix, each type of nucleobase on one strand bonds with just one type of nucleobase on the other strand. This is called

complementary base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

ing. Purines form

hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s to pyrimidines, with adenine bonding only to thymine in two hydrogen bonds, and cytosine bonding only to guanine in three hydrogen bonds. This arrangement of two nucleotides binding together across the double helix (from six-carbon ring to six-carbon ring) is called a Watson-Crick base pair. DNA with high

GC-content is more stable than DNA with low -content. A

Hoogsteen base pair (hydrogen bonding the 6-carbon ring to the 5-carbon ring) is a rare variation of base-pairing.

As hydrogen bonds are not

covalent

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

, they can be broken and rejoined relatively easily. The two strands of DNA in a double helix can thus be pulled apart like a zipper, either by a mechanical force or high

temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making ...

. As a result of this base pair complementarity, all the information in the double-stranded sequence of a DNA helix is duplicated on each strand, which is vital in DNA replication. This reversible and specific interaction between complementary base pairs is critical for all the functions of DNA in organisms.

ssDNA vs. dsDNA

Most DNA molecules are actually two polymer strands, bound together in a helical fashion by noncovalent bonds; this double-stranded (dsDNA) structure is maintained largely by the intrastrand base stacking interactions, which are strongest for stacks. The two strands can come apart—a process known as melting—to form two single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules. Melting occurs at high temperatures, low salt and high

pH (low pH also melts DNA, but since DNA is unstable due to acid depurination, low pH is rarely used).

The stability of the dsDNA form depends not only on the -content (% basepairs) but also on sequence (since stacking is sequence specific) and also length (longer molecules are more stable). The stability can be measured in various ways; a common way is the

melting temperature (also called ''T

m'' value), which is the temperature at which 50% of the double-strand molecules are converted to single-strand molecules; melting temperature is dependent on ionic strength and the concentration of DNA. As a result, it is both the percentage of base pairs and the overall length of a DNA double helix that determines the strength of the association between the two strands of DNA. Long DNA helices with a high -content have more strongly interacting strands, while short helices with high content have more weakly interacting strands. In biology, parts of the DNA double helix that need to separate easily, such as the

Pribnow box in some

promoters, tend to have a high content, making the strands easier to pull apart.

In the laboratory, the strength of this interaction can be measured by finding the melting temperature ''T

m'' necessary to break half of the hydrogen bonds. When all the base pairs in a DNA double helix melt, the strands separate and exist in solution as two entirely independent molecules. These single-stranded DNA molecules have no single common shape, but some conformations are more stable than others.

Amount

In humans, the total female

diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

nuclear genome per cell extends for 6.37 Gigabase pairs (Gbp), is 208.23 cm long and weighs 6.51 picograms (pg).

Male values are 6.27 Gbp, 205.00 cm, 6.41 pg.

Each DNA polymer can contain hundreds of millions of nucleotides, such as in

chromosome 1. Chromosome 1 is the largest human

chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

with approximately 220 million

base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s, and would be long if straightened.

In

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s, in addition to

nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. ...

, there is also

mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

(mtDNA) which encodes certain proteins used by the mitochondria. The mtDNA is usually relatively small in comparison to the nuclear DNA. For example, the

human mitochondrial DNA forms closed circular molecules, each of which contains 16,569

DNA base pairs,

with each such molecule normally containing a full set of the mitochondrial genes. Each human mitochondrion contains, on average, approximately 5 such mtDNA molecules.

[ Each human cell contains approximately 100 mitochondria, giving a total number of mtDNA molecules per human cell of approximately 500.][ However, the amount of mitochondria per cell also varies by cell type, and an ]egg cell

The egg cell or ovum (: ova) is the female Reproduction, reproductive cell, or gamete, in most anisogamous organisms (organisms that reproduce sexually with a larger, female gamete and a smaller, male one). The term is used when the female game ...

can contain 100,000 mitochondria, corresponding to up to 1,500,000 copies of the mitochondrial genome (constituting up to 90% of the DNA of the cell).

Sense and antisense

A DNA sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nu ...

is called a "sense" sequence if it is the same as that of a messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

copy that is translated into protein. The sequence on the opposite strand is called the "antisense" sequence. Both sense and antisense sequences can exist on different parts of the same strand of DNA (i.e. both strands can contain both sense and antisense sequences). In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, antisense RNA sequences are produced, but the functions of these RNAs are not entirely clear. One proposal is that antisense RNAs are involved in regulating gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

through RNA-RNA base pairing.

A few DNA sequences in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and more in plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

s and virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es, blur the distinction between sense and antisense strands by having overlapping genes. In these cases, some DNA sequences do double duty, encoding one protein when read along one strand, and a second protein when read in the opposite direction along the other strand. In bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, this overlap may be involved in the regulation of gene transcription, while in viruses, overlapping genes increase the amount of information that can be encoded within the small viral genome.

Supercoiling

DNA can be twisted like a rope in a process called DNA supercoiling. With DNA in its "relaxed" state, a strand usually circles the axis of the double helix once every 10.4 base pairs, but if the DNA is twisted the strands become more tightly or more loosely wound. If the DNA is twisted in the direction of the helix, this is positive supercoiling, and the bases are held more tightly together. If they are twisted in the opposite direction, this is negative supercoiling, and the bases come apart more easily. In nature, most DNA has slight negative supercoiling that is introduced by enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s called topoisomerases.DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

.

Alternative DNA structures

DNA exists in many possible conformations that include A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA forms, although only B-DNA and Z-DNA have been directly observed in functional organisms.

DNA exists in many possible conformations that include A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA forms, although only B-DNA and Z-DNA have been directly observed in functional organisms.in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

'' B-DNA X-ray diffraction-scattering patterns of highly hydrated DNA fibers in terms of squares of Bessel function

Bessel functions, named after Friedrich Bessel who was the first to systematically study them in 1824, are canonical solutions of Bessel's differential equation

x^2 \frac + x \frac + \left(x^2 - \alpha^2 \right)y = 0

for an arbitrary complex ...

s.James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biology, molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper in ''Nature (journal), Nature'' proposing the Nucleic acid ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the Nucleic acid doub ...

presented their molecular modeling analysis of the DNA X-ray diffraction patterns to suggest that the structure was a double helix.right-handed

In human biology, handedness is an individual's preferential use of one hand, known as the dominant hand, due to and causing it to be stronger, faster or more Fine motor skill, dextrous. The other hand, comparatively often the weaker, less dext ...

spiral, with a shallow, wide minor groove and a narrower, deeper major groove. The A form occurs under non-physiological conditions in partly dehydrated samples of DNA, while in the cell it may be produced in hybrid pairings of DNA and RNA strands, and in enzyme-DNA complexes. Segments of DNA where the bases have been chemically modified by methylation may undergo a larger change in conformation and adopt the Z form. Here, the strands turn about the helical axis in a left-handed spiral, the opposite of the more common B form. These unusual structures can be recognized by specific Z-DNA binding proteins and may be involved in the regulation of transcription.

Alternative DNA chemistry

For many years, exobiologists have proposed the existence of a shadow biosphere, a postulated microbial biosphere

The biosphere (), also called the ecosphere (), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be termed the zone of life on the Earth. The biosphere (which is technically a spherical shell) is virtually a closed system with regard to mat ...

of Earth that uses radically different biochemical and molecular processes than currently known life. One of the proposals was the existence of lifeforms that use arsenic instead of phosphorus in DNA. A report in 2010 of the possibility in the bacterium

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the ...

GFAJ-1 was announced,

Quadruplex structures

At the ends of the linear chromosomes are specialized regions of DNA called

At the ends of the linear chromosomes are specialized regions of DNA called telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes (see #Sequences, Sequences). Telomeres are a widespread genetic feature most commonly found in eukaryotes. In ...

s. The main function of these regions is to allow the cell to replicate chromosome ends using the enzyme telomerase, as the enzymes that normally replicate DNA cannot copy the extreme 3′ ends of chromosomes.DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell (biology), cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is cons ...

systems in the cell from treating them as damage to be corrected.human cells

The list of human cell types provides an enumeration and description of the various specialized cells found within the human body, highlighting their distinct functions, characteristics, and contributions to overall physiological processes. Cell ...

, telomeres are usually lengths of single-stranded DNA containing several thousand repeats of a simple TTAGGG sequence.

These guanine-rich sequences may stabilize chromosome ends by forming structures of stacked sets of four-base units, rather than the usual base pairs found in other DNA molecules. Here, four guanine bases, known as a guanine tetrad, form a flat plate. These flat four-base units then stack on top of each other to form a stable G-quadruplex structure.

Branched DNA

Branched DNA can form networks containing multiple branches.

In DNA, fraying occurs when non-complementary regions exist at the end of an otherwise complementary double-strand of DNA. However, branched DNA can occur if a third strand of DNA is introduced and contains adjoining regions able to hybridize with the frayed regions of the pre-existing double-strand. Although the simplest example of branched DNA involves only three strands of DNA, complexes involving additional strands and multiple branches are also possible. Branched DNA can be used in nanotechnology

Nanotechnology is the manipulation of matter with at least one dimension sized from 1 to 100 nanometers (nm). At this scale, commonly known as the nanoscale, surface area and quantum mechanical effects become important in describing propertie ...

to construct geometric shapes, see the section on uses in technology below.

Artificial bases

Several artificial nucleobases have been synthesized, and successfully incorporated in the eight-base DNA analogue named Hachimoji DNA. Dubbed S, B, P, and Z, these artificial bases are capable of bonding with each other in a predictable way (S–B and P–Z), maintain the double helix structure of DNA, and be transcribed to RNA. Their existence could be seen as an indication that there is nothing special about the four natural nucleobases that evolved on Earth. On the other hand, DNA is tightly related to RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

which does not only act as a transcript of DNA but also performs as molecular machines many tasks in cells. For this purpose it has to fold into a structure. It has been shown that to allow to create all possible structures at least four bases are required for the corresponding RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

, while a higher number is also possible but this would be against the natural principle of least effort.

Acidity

The phosphate groups of DNA give it similar acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

ic properties to phosphoric acid

Phosphoric acid (orthophosphoric acid, monophosphoric acid or phosphoric(V) acid) is a colorless, odorless phosphorus-containing solid, and inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is commonly encountered as an 85% aqueous solution, ...

and it can be considered as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbolised by the chemical formula , to dissociate into a hydron (chemistry), proton, , and an anion, . The Dissociation (chemistry), dissociation or ionization of a strong acid in solution is effectivel ...

. It will be fully ionized at a normal cellular pH, releasing proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

s which leave behind negative charges on the phosphate groups. These negative charges protect DNA from breakdown by hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

by repelling nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

s which could hydrolyze it.

Macroscopic appearance

Pure DNA extracted from cells forms white, stringy clumps.

Chemical modifications and altered DNA packaging

Base modifications and DNA packaging

Structure of cytosine with and without the 5-methyl group.

Deamination

Deamination is the removal of an amino group from a molecule. Enzymes that catalysis, catalyse this reaction are called deaminases.

In the human body, deamination takes place primarily in the liver; however, it can also occur in the kidney. In s ...

converts 5-methylcytosine into thymine.

The expression of genes is influenced by how the DNA is packaged in chromosomes, in a structure called chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important r ...

. Base modifications can be involved in packaging, with regions that have low or no gene expression usually containing high levels of methylation of cytosine

Cytosine () (symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleotide bases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attac ...

bases. DNA packaging and its influence on gene expression can also occur by covalent modifications of the histone protein core around which DNA is wrapped in the chromatin structure or else by remodeling carried out by chromatin remodeling complexes (see Chromatin remodeling). There is, further, crosstalk

In electronics, crosstalk (XT) is a phenomenon by which a signal transmitted on one circuit or channel of a transmission system creates an undesired effect in another circuit or channel. Crosstalk is usually caused by undesired capacitive, ...

between DNA methylation and histone modification, so they can coordinately affect chromatin and gene expression.

For one example, cytosine methylation produces 5-methylcytosine, which is important for X-inactivation of chromosomes. The average level of methylation varies between organisms—the worm ''Caenorhabditis elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a Hybrid word, blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''r ...

'' lacks cytosine methylation, while vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s have higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine. Despite the importance of 5-methylcytosine, it can deaminate to leave a thymine base, so methylated cytosines are particularly prone to mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s. Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria, the presence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

, and the glycosylation

Glycosylation is the reaction in which a carbohydrate (or ' glycan'), i.e. a glycosyl donor, is attached to a hydroxyl or other functional group of another molecule (a glycosyl acceptor) in order to form a glycoconjugate. In biology (but not ...

of uracil to produce the "J-base" in kinetoplastids.

Damage

DNA can be damaged by many sorts of mutagens, which change the

DNA can be damaged by many sorts of mutagens, which change the DNA sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nu ...

. Mutagens include oxidizing agents, alkylating agents and also high-energy electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

such as ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

light and X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

s. The type of DNA damage produced depends on the type of mutagen. For example, UV light can damage DNA by producing thymine dimers, which are cross-links between pyrimidine bases. On the other hand, oxidants such as free radicals or hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscosity, viscous than Properties of water, water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usua ...

produce multiple forms of damage, including base modifications, particularly of guanosine, and double-strand breaks. A typical human cell contains about 150,000 bases that have suffered oxidative damage. Of these oxidative lesions, the most dangerous are double-strand breaks, as these are difficult to repair and can produce point mutations, insertions, deletions from the DNA sequence, and chromosomal translocation

In genetics, chromosome translocation is a phenomenon that results in unusual rearrangement of chromosomes. This includes "balanced" and "unbalanced" translocation, with three main types: "reciprocal", "nonreciprocal" and "Robertsonian" transloc ...

s. These mutations can cause cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

. Because of inherent limits in the DNA repair mechanisms, if humans lived long enough, they would all eventually develop cancer.naturally occurring

A natural product is a natural compound or substance produced by a living organism—that is, found in nature. In the broadest sense, natural products include any substance produced by life. Natural products can also be prepared by chemical ...

, due to normal cellular processes that produce reactive oxygen species, the hydrolytic activities of cellular water, etc., also occur frequently. Although most of these damages are repaired, in any cell some DNA damage may remain despite the action of repair processes. These remaining DNA damages accumulate with age in mammalian postmitotic tissues. This accumulation appears to be an important underlying cause of aging.

Many mutagens fit into the space between two adjacent base pairs, this is called '' intercalation''. Most intercalators are aromatic

In organic chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property describing the way in which a conjugated system, conjugated ring of unsaturated bonds, lone pairs, or empty orbitals exhibits a stabilization stronger than would be expected from conjugati ...

and planar molecules; examples include ethidium bromide, acridines, daunomycin, and doxorubicin. For an intercalator to fit between base pairs, the bases must separate, distorting the DNA strands by unwinding of the double helix. This inhibits both transcription and DNA replication, causing toxicity and mutations. As a result, DNA intercalators may be carcinogen

A carcinogen () is any agent that promotes the development of cancer. Carcinogens can include synthetic chemicals, naturally occurring substances, physical agents such as ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, and biologic agents such as viruse ...

s, and in the case of thalidomide, a teratogen. Others such as benzo 'a''yrene diol epoxide and aflatoxin form DNA adducts that induce errors in replication. Nevertheless, due to their ability to inhibit DNA transcription and replication, other similar toxins are also used in chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated chemo, sometimes CTX and CTx) is the type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (list of chemotherapeutic agents, chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) in a standard chemotherapy re ...

to inhibit rapidly growing cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

cells.

Biological functions

DNA usually occurs as linear

DNA usually occurs as linear chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

s in eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s, and circular chromosomes in prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s. The set of chromosomes in a cell makes up its genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

; the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondria. These ar ...

has approximately 3 billion base pairs of DNA arranged into 46 chromosomes.sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is cal ...

of pieces of DNA called gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s. Transmission of genetic information in genes is achieved via complementary base pairing. For example, in transcription, when a cell uses the information in a gene, the DNA sequence is copied into a complementary RNA sequence through the attraction between the DNA and the correct RNA nucleotides. Usually, this RNA copy is then used to make a matching protein sequence in a process called translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

, which depends on the same interaction between RNA nucleotides. In an alternative fashion, a cell may copy its genetic information in a process called DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

. The details of these functions are covered in other articles; here the focus is on the interactions between DNA and other molecules that mediate the function of the genome.

Genes and genomes

Genomic DNA is tightly and orderly packed in the process called DNA condensation, to fit the small available volumes of the cell. In eukaryotes, DNA is located in the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (; : nuclei) is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have #Anucleated_cells, ...

, with small amounts in mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

and chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

s. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid. The genetic information in a genome is held within genes, and the complete set of this information in an organism is called its genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

. A gene is a unit of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

and is a region of DNA that influences a particular characteristic in an organism. Genes contain an open reading frame

In molecular biology, reading frames are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible reading frames ...

that can be transcribed, and regulatory sequences such as promoters and enhancers, which control transcription of the open reading frame.

In many species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, only a small fraction of the total sequence of the genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

encodes protein. For example, only about 1.5% of the human genome consists of protein-coding exon

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequence ...

s, with over 50% of human DNA consisting of non-coding repetitive sequences. The reasons for the presence of so much noncoding DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, microRNA, piRNA, ribosomal RNA, and regu ...

in eukaryotic genomes and the extraordinary differences in genome size, or '' C-value'', among species, represent a long-standing puzzle known as the " C-value enigma". However, some DNA sequences that do not code protein may still encode functional non-coding RNA

A non-coding RNA (ncRNA) is a functional RNA molecule that is not Translation (genetics), translated into a protein. The DNA sequence from which a functional non-coding RNA is transcribed is often called an RNA gene. Abundant and functionally imp ...

molecules, which are involved in the regulation of gene expression

Regulation of gene expression, or gene regulation, includes a wide range of mechanisms that are used by cells to increase or decrease the production of specific gene products (protein or RNA). Sophisticated programs of gene expression are wide ...

. Some noncoding DNA sequences play structural roles in chromosomes.

Some noncoding DNA sequences play structural roles in chromosomes. Telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes (see #Sequences, Sequences). Telomeres are a widespread genetic feature most commonly found in eukaryotes. In ...

s and centromeres typically contain few genes but are important for the function and stability of chromosomes.pseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Pseudogenes can be formed from both protein-coding genes and non-coding genes. In the case of protein-coding genes, most pseudogenes arise as superfluous copies of fun ...

s, which are copies of genes that have been disabled by mutation. These sequences are usually just molecular fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s, although they can occasionally serve as raw genetic material

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic aci ...

for the creation of new genes through the process of gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene ...

and divergence

In vector calculus, divergence is a vector operator that operates on a vector field, producing a scalar field giving the rate that the vector field alters the volume in an infinitesimal neighborhood of each point. (In 2D this "volume" refers to ...

.

Transcription and translation

A gene is a sequence of DNA that contains genetic information and can influence the phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

of an organism. Within a gene, the sequence of bases along a DNA strand defines a messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

sequence, which then defines one or more protein sequences. The relationship between the nucleotide sequences of genes and the amino-acid sequences of proteins is determined by the rules of translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

, known collectively as the genetic code

Genetic code is a set of rules used by living cell (biology), cells to Translation (biology), translate information encoded within genetic material (DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished ...

. The genetic code consists of three-letter 'words' called ''codons'' formed from a sequence of three nucleotides (e.g. ACT, CAG, TTT).

In transcription, the codons of a gene are copied into messenger RNA by RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactions that synthesize RNA from a DNA template.

Using the e ...

. This RNA copy is then decoded by a ribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

that reads the RNA sequence by base-pairing the messenger RNA to transfer RNA, which carries amino acids. Since there are 4 bases in 3-letter combinations, there are 64 possible codons (43 combinations). These encode the twenty standard amino acids, giving most amino acids more than one possible codon. There are also three 'stop' or 'nonsense' codons signifying the end of the coding region; these are the TAG, TAA, and TGA codons, (UAG, UAA, and UGA on the mRNA).

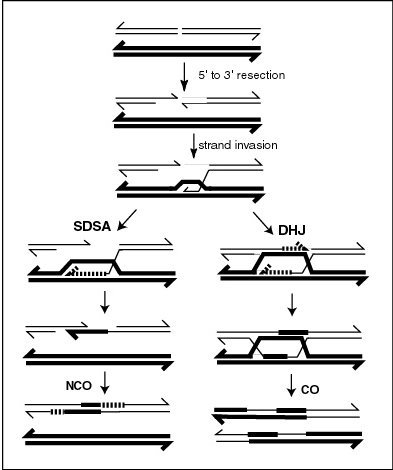

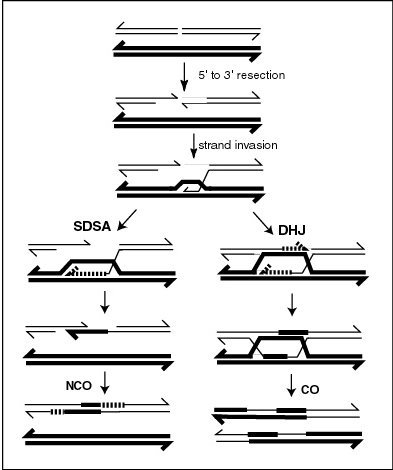

Replication

Cell division is essential for an organism to grow, but, when a cell divides, it must replicate the DNA in its genome so that the two daughter cells have the same genetic information as their parent. The double-stranded structure of DNA provides a simple mechanism for

Cell division is essential for an organism to grow, but, when a cell divides, it must replicate the DNA in its genome so that the two daughter cells have the same genetic information as their parent. The double-stranded structure of DNA provides a simple mechanism for DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

. Here, the two strands are separated and then each strand's complementary DNA sequence is recreated by an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

called DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create t ...

. This enzyme makes the complementary strand by finding the correct base through complementary base pairing and bonding it onto the original strand. As DNA polymerases can only extend a DNA strand in a 5′ to 3′ direction, different mechanisms are used to copy the antiparallel strands of the double helix. In this way, the base on the old strand dictates which base appears on the new strand, and the cell ends up with a perfect copy of its DNA.

Extracellular nucleic acids

Naked extracellular DNA (eDNA), most of it released by cell death, is nearly ubiquitous in the environment. Its concentration in soil may be as high as 2 μg/L, and its concentration in natural aquatic environments may be as high at 88 μg/L.horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

;biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s of several bacterial species. It may act as a recognition factor to regulate the attachment and dispersal of specific cell types in the biofilm;ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

, monitoring the movements and presence of species in water, air, or on land, and assessing an area's biodiversity.

Neutrophil extracellular traps

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are networks of extracellular fibers, primarily composed of DNA, which allow neutrophils, a type of white blood cell, to kill extracellular pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cells.

Interactions with proteins

All the functions of DNA depend on interactions with proteins. These protein interactions can be non-specific, or the protein can bind specifically to a single DNA sequence. Enzymes can also bind to DNA and of these, the polymerases that copy the DNA base sequence in transcription and DNA replication are particularly important.

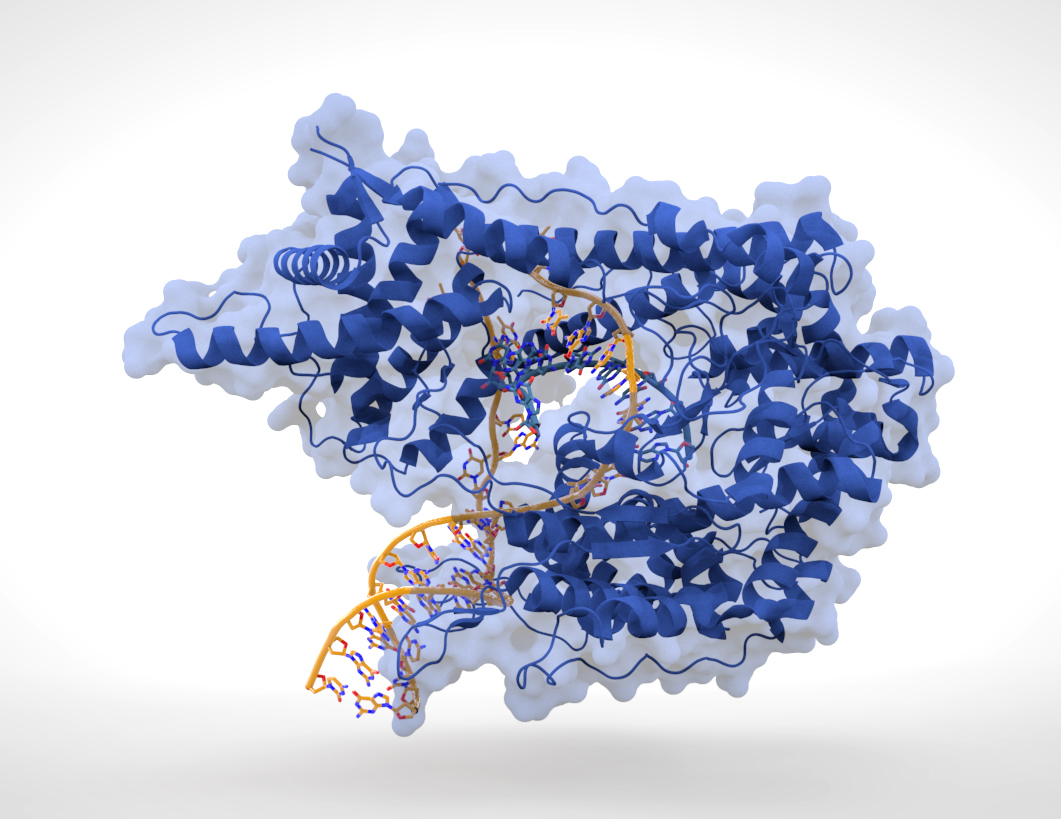

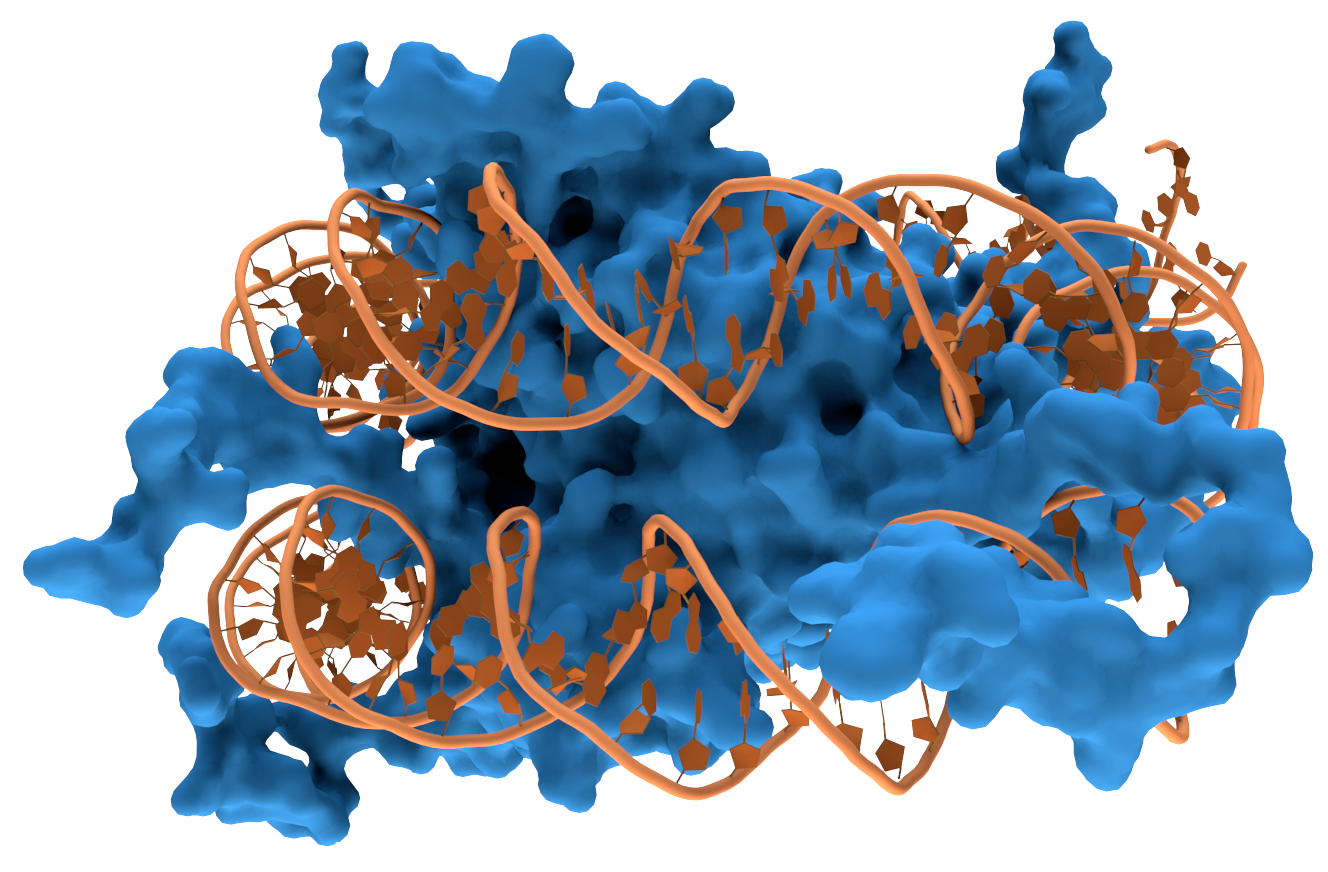

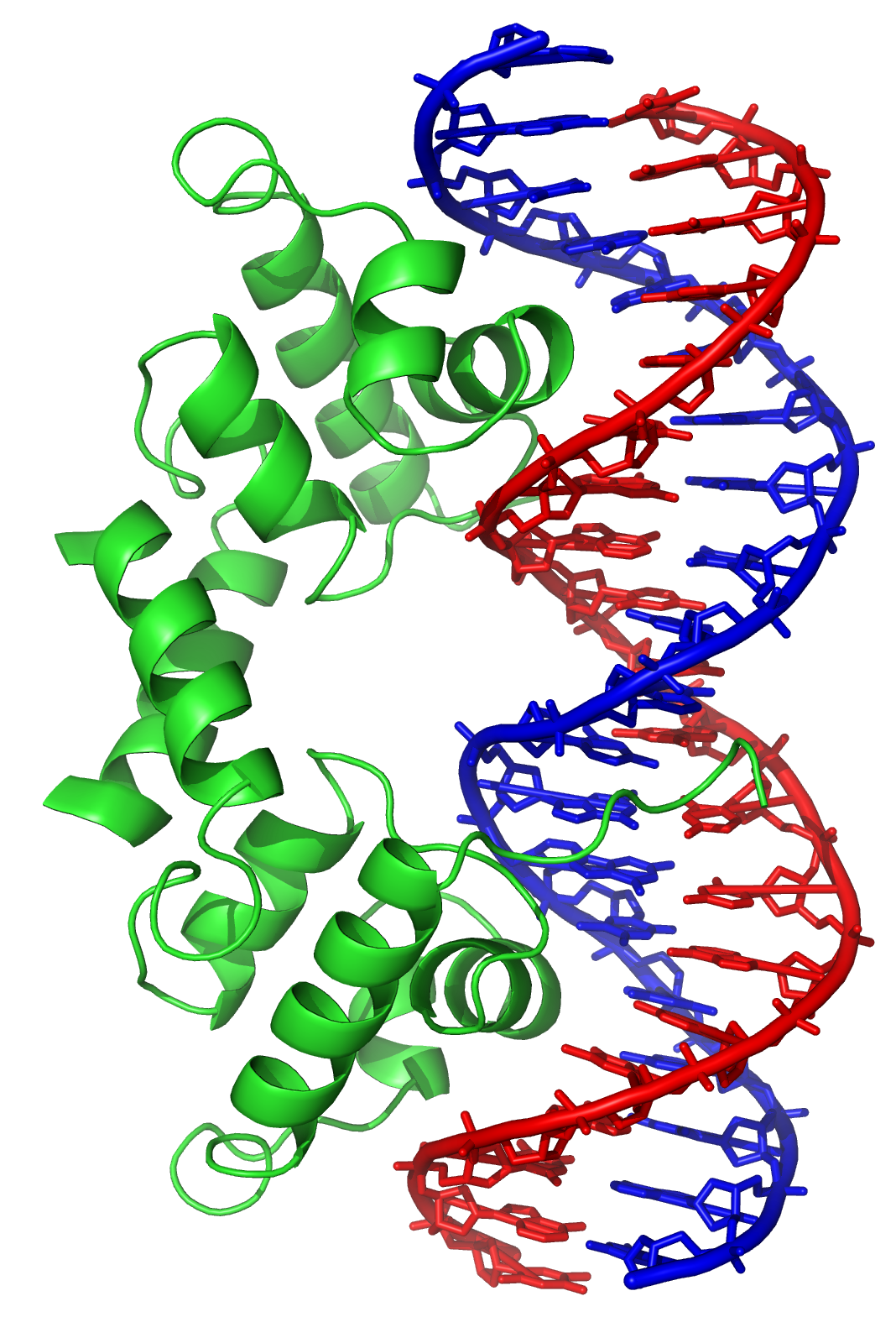

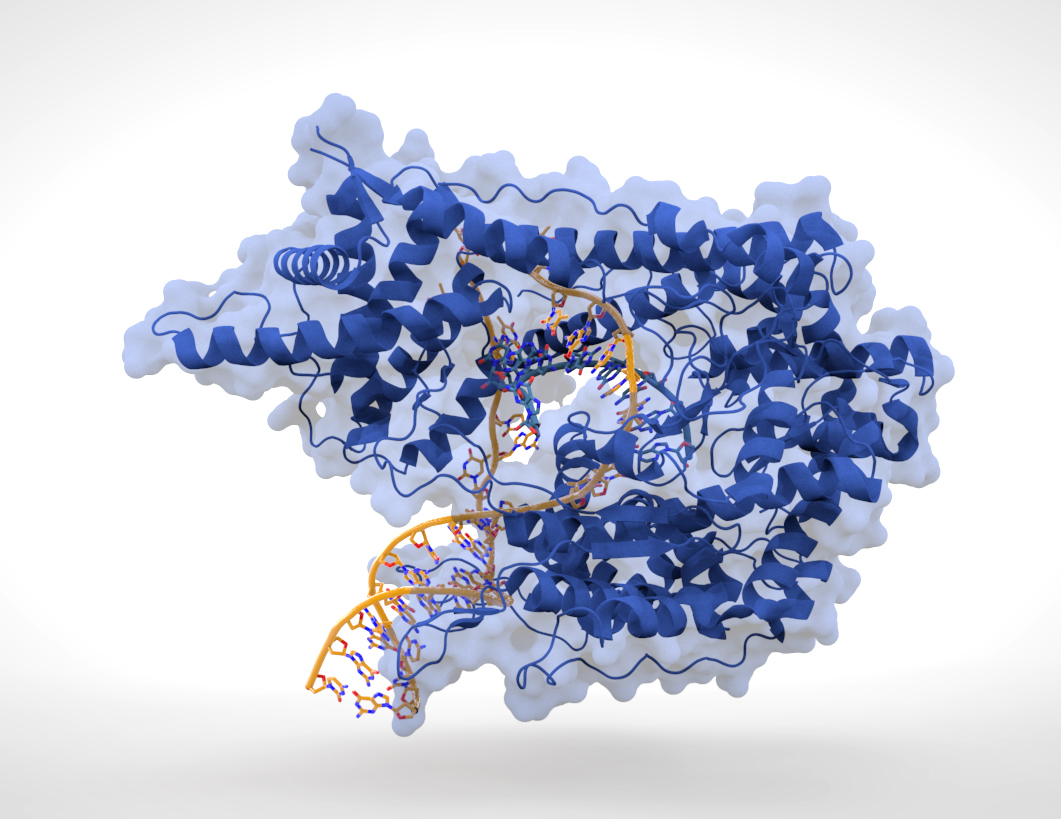

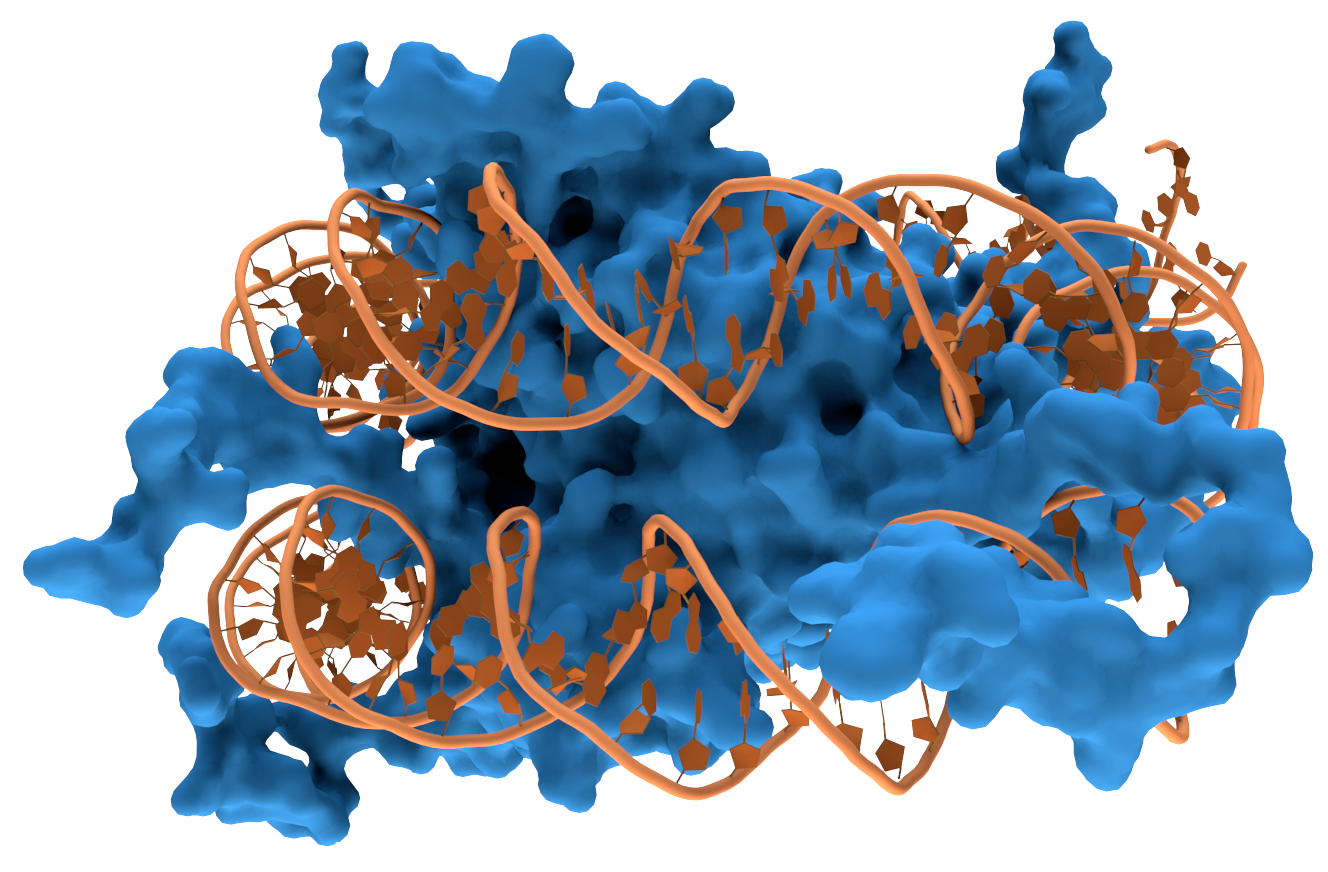

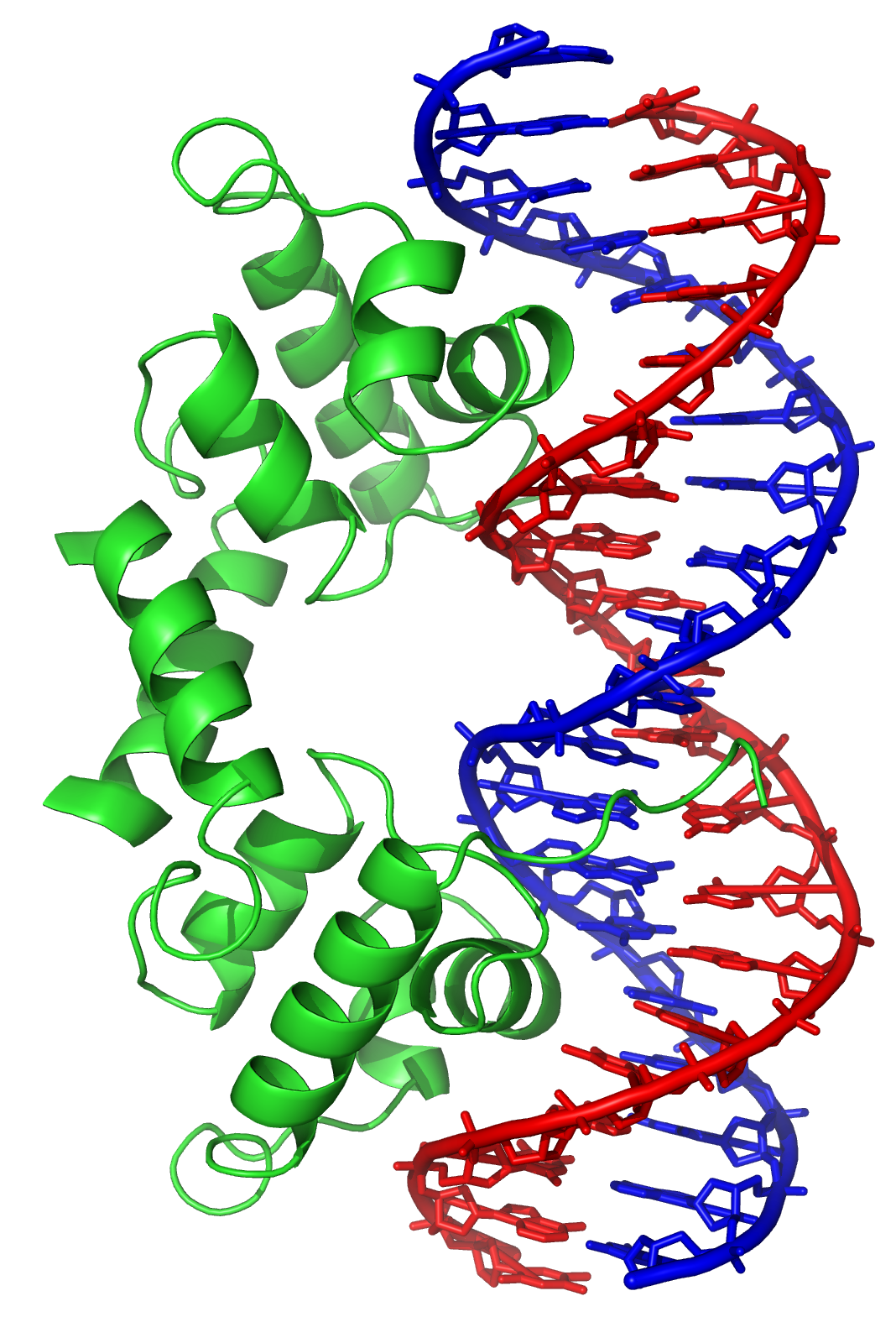

DNA-binding proteins

Structural proteins that bind DNA are well-understood examples of non-specific DNA-protein interactions. Within chromosomes, DNA is held in complexes with structural proteins. These proteins organize the DNA into a compact structure called

Structural proteins that bind DNA are well-understood examples of non-specific DNA-protein interactions. Within chromosomes, DNA is held in complexes with structural proteins. These proteins organize the DNA into a compact structure called chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important r ...

. In eukaryotes, this structure involves DNA binding to a complex of small basic proteins called histones, while in prokaryotes multiple types of proteins are involved. The histones form a disk-shaped complex called a nucleosome

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone, histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a bobbin, spool. The nucleosome ...

, which contains two complete turns of double-stranded DNA wrapped around its surface. These non-specific interactions are formed through basic residues in the histones, making ionic bond

Ionic bonding is a type of chemical bond

A chemical bond is the association of atoms or ions to form molecules, crystals, and other structures. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic ...

s to the acidic sugar-phosphate backbone of the DNA, and are thus largely independent of the base sequence. Chemical modifications of these basic amino acid residues include methylation, phosphorylation

In biochemistry, phosphorylation is described as the "transfer of a phosphate group" from a donor to an acceptor. A common phosphorylating agent (phosphate donor) is ATP and a common family of acceptor are alcohols:

:

This equation can be writ ...