D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson CB FRS

D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson Biography

School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland, October 2003, retrieved 30 March 2016 and he was brought up by his maternal grandfather Joseph Gamgee (1801–1895), David Raitt Robertson Burtbr>Obituary

in James B Salmond (ed.), Veterum Laudes (Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh, 1950), 108–119 a veterinary surgeon. He lived with his grandfather and uncle, John Gamgee, at 12 Castle Terrace, facing north onto

, The Scotman, 22 June 1948 As a student at Cambridge, D'Arcy Thompson was first a

University of Dundee, External Relations, Press Office, 14 March 2006 His final report for the government drew attention also to the near extinction of the Whilst in Dundee, Thompson sat on the committee of management of the Dundee Private Hospital for Women. He was a founder member of the Dundee Social Union and pressed for it "to buy four slum properties in the town", which they renovated so that "the poorest families of Dundee could live there." He encouraged and supported the social reformer Mary Lily Walker in her work with the social union.

In 1917, aged 57, Thompson was appointed to the Chair of Natural History at the

Whilst in Dundee, Thompson sat on the committee of management of the Dundee Private Hospital for Women. He was a founder member of the Dundee Social Union and pressed for it "to buy four slum properties in the town", which they renovated so that "the poorest families of Dundee could live there." He encouraged and supported the social reformer Mary Lily Walker in her work with the social union.

In 1917, aged 57, Thompson was appointed to the Chair of Natural History at the

Thompson's most famous work, '' On Growth and Form'', led the way for the scientific explanation of morphogenesis, the process by which patterns and body structures are formed in plants and animals. It was written in Dundee, mostly in 1915, though wartime shortages and his many last-minute alterations delayed publication until 1917. The central theme of the book is that biologists of its author's day overemphasized

Thompson's most famous work, '' On Growth and Form'', led the way for the scientific explanation of morphogenesis, the process by which patterns and body structures are formed in plants and animals. It was written in Dundee, mostly in 1915, though wartime shortages and his many last-minute alterations delayed publication until 1917. The central theme of the book is that biologists of its author's day overemphasized

A bibliography of Protozoa, sponges, Coelenterata, and worms, including also the Polyzoa, Brachiopoda, and Tunicata, for the years 1861–1883.

' Cambridge University Press. * 1895.

Glossary of Greek Birds.

' Oxford University Press. * 1897.

Report by Professor D'Arcy Thompson on his mission to the Behring Sea in 1896.

Her Majesty's Stationery Office. * 1910

(translation). * 1913.

On Aristotle as a biologist with a prooemion on Herbert Spencer.

' Oxford University Press. Being the Herbert Spencer lecture delivered before the University of Oxford, 14 February 1913. * 1917.

On Growth and Form

'. Cambridge University Press. :: �

1945 Edition at archive.org

*1940

''Science and the Classics''

Oxford University Press, 264 pp. *1947. Glossary of Greek Fishes.

Original 1945 reprint available online

at

Online

at

D'Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum

Dundee University

School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland * John Milnor

Geometry of Growth and Form: Commentary on D'Arcy Thompson

lecture, Video (55min), Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Stony Brook University, 24 September 2010

Biography, Authors JOC/EFR © October 2003, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland * {{DEFAULTSORT:Thompson, Darcy Wentworth 1860 births 1948 deaths 19th-century British zoologists 20th-century Scottish zoologists Academics from Edinburgh Academics of the University of Dundee Academics of the University of St Andrews Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Companions of the Order of the Bath Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Knights Bachelor International members of the American Philosophical Society Museum founders People associated with Fife People educated at Edinburgh Academy Presidents of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society Presidents of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Scientists from Edinburgh Scottish biologists Scottish classical scholars Scottish knights Scottish mathematicians Theoretical biologists

FRSE

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and Literature, letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". ...

(2 May 1860 – 21 June 1948) was a Scottish biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

, mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

and classics scholar. He was a pioneer of mathematical and theoretical biology, travelled on expeditions to the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

and held the position of Professor of Natural History

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

at University College, Dundee for 32 years, then at St Andrews

St Andrews (; ; , pronounced ʰʲɪʎˈrˠiː.ɪɲ is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourth-largest settleme ...

for 31 years. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, was knighted, and received the Darwin Medal and the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal.

Thompson is remembered as the author of the 1917 book '' On Growth and Form'', which led the way for the scientific explanation of morphogenesis, the process by which patterns and body structures are formed in plants and animals.

Thompson's description of the mathematical beauty of nature, and the mathematical basis of the forms of animals and plants, stimulated thinkers as diverse as Julian Huxley, C. H. Waddington, Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer ...

, René Thom, Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( ; ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a Belgian-born French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair o ...

, Eduardo Paolozzi, Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , ; ), was a Swiss-French architectural designer, painter, urban planner and writer, who was one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture ...

, Christopher Alexander and Mies van der Rohe.

Life

Early life

Thompson was born at 3 Brandon Street in Edinburgh to Fanny Gamgee (sister of Sampson Gamgee) and D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1829–1902), Classics Master at Edinburgh Academy and later Professor of Greek at Queen's College, Galway. His mother, Fanny Gamgee (1840–1860), died 9 days after his birth as a result of complicationsJ J O'Connor and E F RobertsoD'Arcy Wentworth Thompson Biography

School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland, October 2003, retrieved 30 March 2016 and he was brought up by his maternal grandfather Joseph Gamgee (1801–1895), David Raitt Robertson Burtbr>Obituary

in James B Salmond (ed.), Veterum Laudes (Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh, 1950), 108–119 a veterinary surgeon. He lived with his grandfather and uncle, John Gamgee, at 12 Castle Terrace, facing north onto

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age. There has been a royal castle on the rock since the reign of Malcol ...

.

From 1870 to 1877 he attended The Edinburgh Academy and won the 1st Edinburgh Academical Club Prize in 1877. In 1878, he matriculated at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

to study medicine. Two years later, he moved to Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

to study zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

.PROF SIR D'ARCY THOMPSON DEAD, The Scotman, 22 June 1948 As a student at Cambridge, D'Arcy Thompson was first a

sizar

At Trinity College Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an Undergraduate education, undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in retur ...

, and then received a scholarship. To earn money to support his education he translated Hermann Müller's work on the fertilisation of flowers, because the topic appealed to him. His translation was published in 1883, and included an introduction by Charles Darwin. He speculated later, that if he had chosen to translate Wilhelm Olbers Focke's hybridisation of flowers, he "might have anticipated the discovery of Mendel by twenty years". He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

degree in Natural Science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

in 1883.

Career

From 1883 to 1884, Thompson stayed in Cambridge as a Junior Demonstrator in physiology, teaching students. In 1884, he was appointed Professor of Biology (later Natural History) at University College, Dundee, a post he held for 32 years. One of his first tasks was to create a Zoology Museum for teaching and research, now named after him. In 1885 he was elected a Fellow of theRoyal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was establis ...

. His proposers were Patrick Geddes, Frank W. Young, William Evans Hoyle and Daniel John Cunningham. He served as vice president to the Society from 1916 to 1919 and as president from 1934 to 1939.

In 1896 and 1897, he went on expeditions to the Bering Straits, representing the British Government in an international inquiry into the fur seal

Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family Otariidae. They are much more closely related to sea lions than Earless seal, true seals, and share with them external ears (Pinna (anatomy ...

industry to assess the fur seal's declining numbers. "Thompson's diplomacy avoided an international incident" between Russia and the United States which both had hunting interests in this area.Lecture Theatre renamed in honour of D'arcy ThompsonUniversity of Dundee, External Relations, Press Office, 14 March 2006 His final report for the government drew attention also to the near extinction of the

sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

and whale populations. He became one of the first to press for conservation agreements, and his recommendations contributed to the issuing of species protection orders. He subsequently was appointed Scientific Adviser to the Fisheries Board of Scotland and later, representative to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea.

He took the opportunity to collect many valuable specimens for his museum, one of the largest in the country at the time, specialising in Arctic zoology, through his links to the Dundee whalers. The D'Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum still has (in 2012) the Japanese spider crab that he collected, and the rare skeleton of a Steller's Sea Cow.

Whilst in Dundee, Thompson sat on the committee of management of the Dundee Private Hospital for Women. He was a founder member of the Dundee Social Union and pressed for it "to buy four slum properties in the town", which they renovated so that "the poorest families of Dundee could live there." He encouraged and supported the social reformer Mary Lily Walker in her work with the social union.

In 1917, aged 57, Thompson was appointed to the Chair of Natural History at the

Whilst in Dundee, Thompson sat on the committee of management of the Dundee Private Hospital for Women. He was a founder member of the Dundee Social Union and pressed for it "to buy four slum properties in the town", which they renovated so that "the poorest families of Dundee could live there." He encouraged and supported the social reformer Mary Lily Walker in her work with the social union.

In 1917, aged 57, Thompson was appointed to the Chair of Natural History at the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

, where he remained for the last 31 years of his life. In 1918 he delivered the Royal Institution Christmas Lecture on ''The Fish of the Sea''. The German British mathematician Walter Ledermann described in his memoir how, as an assistant in Mathematics, he met the biology Professor Thompson at St Andrews in the mid 1930s and how Thompson "was fond of exercising his skills as an amateur of mathematics", that "he used quite sophisticated mathematical methods to elucidate the shapes that occur in the living world" and " ..differential equations, a subject which evidently lay outside d'Arcy Thompson's fields of knowledge at that time." Ledermann wrote how on one occasion he helped him, working and writing out the answer to his question.

In '' Country Life'' magazine in October 1923, he wrote:

Family

On 4 July 1901 Thompson married Maureen, elder daughter of William Drury, of Dublin. His wife and three daughters survived him. He died at his home inSt Andrews

St Andrews (; ; , pronounced ʰʲɪʎˈrˠiː.ɪɲ is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourth-largest settleme ...

after flying home from India in 1948, at the age of 87, having attended the Science Congress at Delhi, and staying in India for some months. Upon returning, "he suffered a breakdown in health, from which he never fully recovered." He is buried with his maternal grandparents, the Gamgees, and half-sisters in Dean Cemetery in western Edinburgh.

Major works

''History of Animals''

In 1910, Thompson published his translation ofAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's '' History of Animals''. He had worked on the enormous task intermittently for many years. It was not the first translation of the book into English, but the earlier attempts by Thomas Taylor (1809) and Richard Cresswell (1862) were inaccurate, and criticised at the time as showing "not only an inadequate knowledge of Greek, but an extremely imperfect acquaintance with zoology". Thompson's version benefited from his excellent Greek, his expertise in zoology, his "full" knowledge of Aristotle's biology

Aristotle's biology is the theory of biology, grounded in systematic observation and collection of data, mainly zoology, zoological, embodied in Aristotle's books on the science. Many of his observations were made during his stay on the island ...

, and his command of the English language, resulting in a fine translation, "correct, free and .. idiomatic". More recently, the evolutionary biologist Armand Leroi admired Thompson's translation:

''On Growth and Form''

Thompson's most famous work, '' On Growth and Form'', led the way for the scientific explanation of morphogenesis, the process by which patterns and body structures are formed in plants and animals. It was written in Dundee, mostly in 1915, though wartime shortages and his many last-minute alterations delayed publication until 1917. The central theme of the book is that biologists of its author's day overemphasized

Thompson's most famous work, '' On Growth and Form'', led the way for the scientific explanation of morphogenesis, the process by which patterns and body structures are formed in plants and animals. It was written in Dundee, mostly in 1915, though wartime shortages and his many last-minute alterations delayed publication until 1917. The central theme of the book is that biologists of its author's day overemphasized evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

as the fundamental determinant of the form and structure of living organisms, and underemphasized the roles of physical laws

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on reproducibility, repeated experiments or observations, that describe or prediction, predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, a ...

and mechanics

Mechanics () is the area of physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among Physical object, physical objects. Forces applied to objects may result in Displacement (vector), displacements, which are changes of ...

.

He had previously criticized Darwinism

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sel ...

in his paper ''Some Difficulties of Darwinism'' in an 1884 meeting for the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

. ''On Growth and Form'' explained in detail why he believed Darwinism to be an inadequate explanation for the origin of new species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

. He did not openly reject natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, but regarded it as secondary to the origin of biological form. Instead, he advocated structuralism

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns t ...

as an alternative to natural selection in governing the form of species, with a hint that vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

was the unseen driving force.

On the concept of allometry, the study of the relationship of body size and shape, Thompson wrote:

Using a mass of examples, Thompson pointed out correlations between biological forms and mechanical phenomena. He showed the similarity in the forms of jellyfish

Jellyfish, also known as sea jellies or simply jellies, are the #Life cycle, medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, which is a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animal ...

and the forms of drops of liquid falling into viscous fluid, and between the internal supporting structures in the hollow bones of birds and well-known engineering truss

A truss is an assembly of ''members'' such as Beam (structure), beams, connected by ''nodes'', that creates a rigid structure.

In engineering, a truss is a structure that "consists of two-force members only, where the members are organized so ...

designs. He described phyllotaxis

In botany, phyllotaxis () or phyllotaxy is the arrangement of leaf, leaves on a plant stem. Phyllotactic spirals form a distinctive class of patterns in nature.

Leaf arrangement

The basic leaf#Arrangement on the stem, arrangements of leaves ...

(numerical relationships between spiral structures in plants) and its relationship to the Fibonacci sequence

In mathematics, the Fibonacci sequence is a Integer sequence, sequence in which each element is the sum of the two elements that precede it. Numbers that are part of the Fibonacci sequence are known as Fibonacci numbers, commonly denoted . Many w ...

.

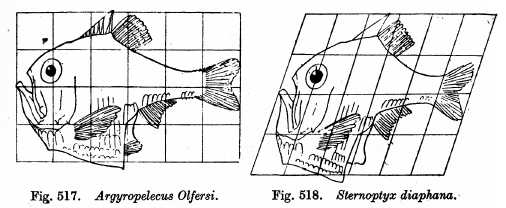

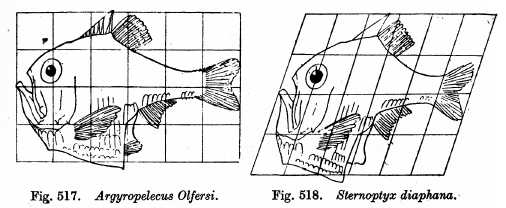

Perhaps the most famous part of the work is chapter XVII, "The Comparison of Related Forms," where Thompson explored the degree to which differences in the forms of related animals could be described by means of relatively simple mathematical transformations.

The book is a work in the "descriptive" tradition; Thompson did not articulate his insights in the form of experimental hypotheses that can be tested. He was aware of this, saying that "This book of mine has little need of preface, for indeed it is 'all preface' from beginning to end."

Honours

Elected a Fellow of theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1916, elected an International honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1928, knighted in 1937 and received the Gold Medal of the Linnean Society in 1938. In 1941, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

.

He was awarded the Darwin Medal in 1946.

For his revised ''On Growth and Form'', he was awarded the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

in 1942. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was establis ...

in 1885, and was active in the Society over many years,

serving as president from 1934 to 1939.

Legacy

Interdisciplinary influence

''On Growth and Form'' has inspired thinkers including the biologists Julian Huxley, Conrad Hal Waddington andStephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ...

, the mathematicians Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer ...

and René Thom, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( ; ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a Belgian-born French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair o ...

and artists including Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Ben Nicholson

Benjamin Lauder Nicholson, OM (10 April 1894 – 6 February 1982) was an English painter of abstract compositions (sometimes in low relief), landscapes, and still-life. He was one of the leading promoters of abstract art in England.

Backg ...

with his ideas on the mathematical basis of the forms of animals, and perhaps especially on morphogenesis. Jackson Pollock

Paul Jackson Pollock (; January 28, 1912August 11, 1956) was an American painter. A major figure in the abstract expressionist movement, Pollock was widely noticed for his "Drip painting, drip technique" of pouring or splashing liquid household ...

owned a copy. Waddington and other developmental biologists were struck particularly by the chapter on Thompson's "Theory of Transformations", where he showed that the various shapes of related species (such as of fish) could be presented as geometric transformations, anticipating the evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as evo-devo, is a field of biological research that compares the developmental biology, developmental processes of different organisms to infer how developmental processes evolution, evolved. ...

of a century later.

The book led Turing to write a famous paper " The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" on how patterns such as those seen on the skins of animals can emerge from a simple chemical system.

Lévi-Strauss cites Thompson in his 1963 book ''Structural Anthropology''.

''On Growth and Form'' is seen as a classic text in architecture and is admired by architects "for its exploration of natural geometries in the dynamics of growth and physical processes." The architects and designers Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , ; ), was a Swiss-French architectural designer, painter, urban planner and writer, who was one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture ...

, László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy (; ; born László Weisz; July 20, 1895 – November 24, 1946) was a Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian painter and photographer as well as a professor in the Bauhaus school. He was highly influenced by Constructivism (art), con ...

and Mies van der Rohe were inspired by the book. Peter Medawar, the 1960 Nobel Laureate in Medicine, called it "the finest work of literature in all the annals of science that have been recorded in the English tongue".

150th anniversary

In 2010, the 150th anniversary of his birth was celebrated with events and exhibitions at the Universities of Dundee and St Andrews; the main lecture theatre in the University of Dundee's Tower Building was renamed in his honour, a publication exploring his work in Dundee and the history of his Zoology Museum was published by University of Dundee Museum Services, and an exhibition on his work was held in the city.Museum and archives

The original Zoology Museum at Dundee became neglected after his move to St Andrews. In 1956 the building, which it was housed in, was scheduled for demolition and the museum collection was dispersed, with some parts going to theBritish Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

. A teaching collection was retained and forms the core of the University of Dundee's current D'Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum.

In 2011, the University of Dundee was awarded a £100,000 grant by The Art Fund to build a collection of art inspired by his ideas and collections, much of it displayed in the Museum.

Special Collections at the University of St Andrews hold Thompson's personal papers which include over 30,000 items. Archive Services at the University of Dundee hold records of his time at Dundee, and a collection of papers relating to Thompson collected by Professor Alexander David Peacock, a later holder of the chair of Natural History at University College, Dundee.

In 1892 D'Arcy Thompson donated Davis Straits specimens of crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s, pycnogonids, and other invertebrates to the Cambridge University Museum of Zoology.

Selected publications

D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson published around 300 articles and books during his career. * 1885.A bibliography of Protozoa, sponges, Coelenterata, and worms, including also the Polyzoa, Brachiopoda, and Tunicata, for the years 1861–1883.

' Cambridge University Press. * 1895.

Glossary of Greek Birds.

' Oxford University Press. * 1897.

Report by Professor D'Arcy Thompson on his mission to the Behring Sea in 1896.

Her Majesty's Stationery Office. * 1910

(translation). * 1913.

On Aristotle as a biologist with a prooemion on Herbert Spencer.

' Oxford University Press. Being the Herbert Spencer lecture delivered before the University of Oxford, 14 February 1913. * 1917.

On Growth and Form

'. Cambridge University Press. :: �

1945 Edition at archive.org

*1940

''Science and the Classics''

Oxford University Press, 264 pp. *1947. Glossary of Greek Fishes.

See also

*Biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations ...

* Evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as evo-devo, is a field of biological research that compares the developmental biology, developmental processes of different organisms to infer how developmental processes evolution, evolved. ...

* Raoul Heinrich Francé (''Die Pflanze als Erfinder'', 1920)

References

Further reading

* Thompson, D. W., 1992. ''On Growth and Form''. Dover reprint of 1942 2nd ed. (1st ed., 1917). *Original 1945 reprint available online

at

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

* --------, 1992. ''On Growth and Form''. Cambridge Univ. Press. Abridged edition by John Tyler Bonner. .

*Online

at

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical charac ...

* Caudwell, C and Jarron, M, 2010. ''D'Arcy Thompson and his Zoology Museum in Dundee''. University of Dundee Museum Services.

* Ruth D'Arcy Thompson, The Remarkable Gamgees (Edinburgh, 1974).

* Ruth D'Arcy Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson : the scholar-naturalist, 1860–1948 (London, 1958).

**postscript by Peter Medawar. Pluto's Republic: Incorporating The Art of the Soluble and Induction and Intuition in Scientific Thought. 368 pages, Oxford University Press (11 November 1982),

* The correspondence and papers of Sir D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860–1948), St Andrews : University Library (1987).

*

* M Kemp, Spirals of life: D'Arcy Thompson and Theodore Cook, with Leonardo and Durer in retrospect, Physis Riv. Internaz. Storia Sci. (NS) 32 (1) (1995), 37–54

*

*

External links

* *D'Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum

Dundee University

School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland * John Milnor

Geometry of Growth and Form: Commentary on D'Arcy Thompson

lecture, Video (55min), Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Stony Brook University, 24 September 2010

Biography, Authors JOC/EFR © October 2003, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland * {{DEFAULTSORT:Thompson, Darcy Wentworth 1860 births 1948 deaths 19th-century British zoologists 20th-century Scottish zoologists Academics from Edinburgh Academics of the University of Dundee Academics of the University of St Andrews Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Companions of the Order of the Bath Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Knights Bachelor International members of the American Philosophical Society Museum founders People associated with Fife People educated at Edinburgh Academy Presidents of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society Presidents of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Scientists from Edinburgh Scottish biologists Scottish classical scholars Scottish knights Scottish mathematicians Theoretical biologists