Crisis of the Roman Republic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The crisis of the Roman Republic was an extended period of political instability and social unrest from about to 44 BC that culminated in the demise of the

After the

After the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and the advent of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.

The causes and attributes of the crisis changed throughout the decades, including brigandage

Brigandage is the life and practice of highway robbery and plunder. It is practiced by a brigand, a person who is typically part of a gang and lives by pillage and robbery.Oxford English Dictionary second edition, 1989. "Brigand.2" first recorded ...

, wars internal and external, overwhelming corruption, land reform, the expansion of Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

, and even the changing composition of the Roman army

The Roman army () served ancient Rome and the Roman people, enduring through the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC), the Roman Republic (509–27 BC), and the Roman Empire (27 BC–AD 1453), including the Western Roman Empire (collapsed Fall of the W ...

.

Modern scholars also disagree about the nature of the crisis. Traditionally, the expansion of citizenship (with all its rights, privileges, and duties) was looked upon negatively by the contemporary Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (, ; –35 BC), was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became a partisan of Julius ...

, the modern Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

, and others of their respective schools, both ancient and modern, because it caused internal dissension, disputes with Rome's Italian allies, slave revolts, and riots.Fields, p. 41, citing Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (, ; –35 BC), was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became a partisan of Julius ...

, ''Iugurthinum'' 86.2. However, other scholars have argued that as the Republic was meant to be ''res publica

', also spelled ''rēs pūblica'' to indicate vowel length, is a Latin phrase, loosely meaning "public affair". It is the root of the ''republic'', and '' commonwealth'' has traditionally been used as a synonym for it; however, translations var ...

'' – the essential thing of the people – the poor and disenfranchised cannot be blamed for trying to redress their legitimate and legal

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a Socia ...

grievances.

Arguments on a single crisis

More recently, beyond arguments about when the crisis of the Republic began (see below), there also has been disagreement whether events comprised a singular or multiple crisis. Harriet Flower, in 2010, proposed a different paradigm encompassing multiple "republics" for the general whole of the traditional republican period with attempts at reform rather than a single "crisis" occurring over a period of eighty years. Instead of a single crisis of the late Republic, Flower proposes a series of crises and transitional periods (excerpted only to the chronological periods after 139 BC): Each different republic had different circumstances and while overarching themes can be traced, "there was no ''single, long'' republic that carried the seeds of its own destruction in its aggressive tendency to expand and in the unbridled ambitions of its leading politicians". The implications of this view put the fall of the republic in a context based around the collapse of the republican political culture of the ''nobiles'' and emphasis onSulla's civil war

Sulla's civil war was fought between the Roman general Sulla and his opponents, the Cinna-Marius faction (usually called the Marians or the Cinnans after their former leaders Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna), in the years 83–82 BC. ...

followed by the fall of Sulla's republic in Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

.

Dating the crisis

For centuries, historians have argued about the start, specific crises involved, and end date for the crisis of the Roman Republic. As aculture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

(or "web of institutions"), Florence Dupont and Christopher Woodall wrote, "no distinction is made between different periods." However, referencing Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

's opinion in his '' History of Rome'', they assert that Romans lost liberty through their own conquests' "morally undermining consequences."

Arguments for an early start-date (c. 134 to 73 BC)

Von Ungern-Sternberg argues for an exact start date of 10 December 134 BC, with the inauguration ofTiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

as tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the Tribune of the Plebs, tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs ac ...

, or alternately, when he first issued his proposal for land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

in 133 BC. Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; ; ; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who prospered during the reigns of the Roman Emperors Trajan, Hadrian, and Antoninus Pius.

He was born c. 95 in Alexandria. After holding the senior offices in the pr ...

of Alexandria wrote that this political crisis was "the preface to ... the Roman civil wars". Velleius

Marcus Velleius Paterculus (; ) was a Roman historian, soldier and senator. His Roman history, written in a highly rhetorical style, covered the period from the end of the Trojan War to AD 30, but is most useful for the period from the death o ...

commented that it was Gracchus' unprecedented standing for re-election as tribune in 133 BC, and the riots and controversy it engendered, which started the crisis:

In any case, the assassination of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC marked "a turning point in Roman history and the beginning of the crisis of the Roman Republic."

Barbette S. Spaeth specifically refers to "the Gracchan crisis at the beginning of the Late Roman Republic ...".Spaeth (1996), p. 73.

Nic Fields, in his popular history of Spartacus

Spartacus (; ) was a Thracians, Thracian gladiator (Thraex) who was one of the Slavery in ancient Rome, escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a major Slave rebellion, slave uprising against the Roman Republic.

Historical accounts o ...

, argues for a start date of 135 BC with the beginning of the First Servile War

The First Servile War of 135–132 BC was a slave rebellion against the Roman Republic, which took place in Sicily. The revolt started in 135 when Eunus, a slave from Syria who claimed to be a prophet, captured the city of Enna in the middl ...

in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. Fields asserts:

The start of the Social War (91–87 BC)

The Social War (from Latin , "war of the allies"), also called the Italian War or the Marsic War, was fought largely from 91 to 88 BC between the Roman Republic and several of its autonomous allies () in Roman Italy, Italy. Some of the ...

, when Rome's nearby Italian allies rebelled against her rule, may be thought of as the beginning of the end of the Republic. Fields also suggests that things got much worse with the Samnite engagement at the Battle of the Colline Gate in 82 BC, the climax of the war between Sulla

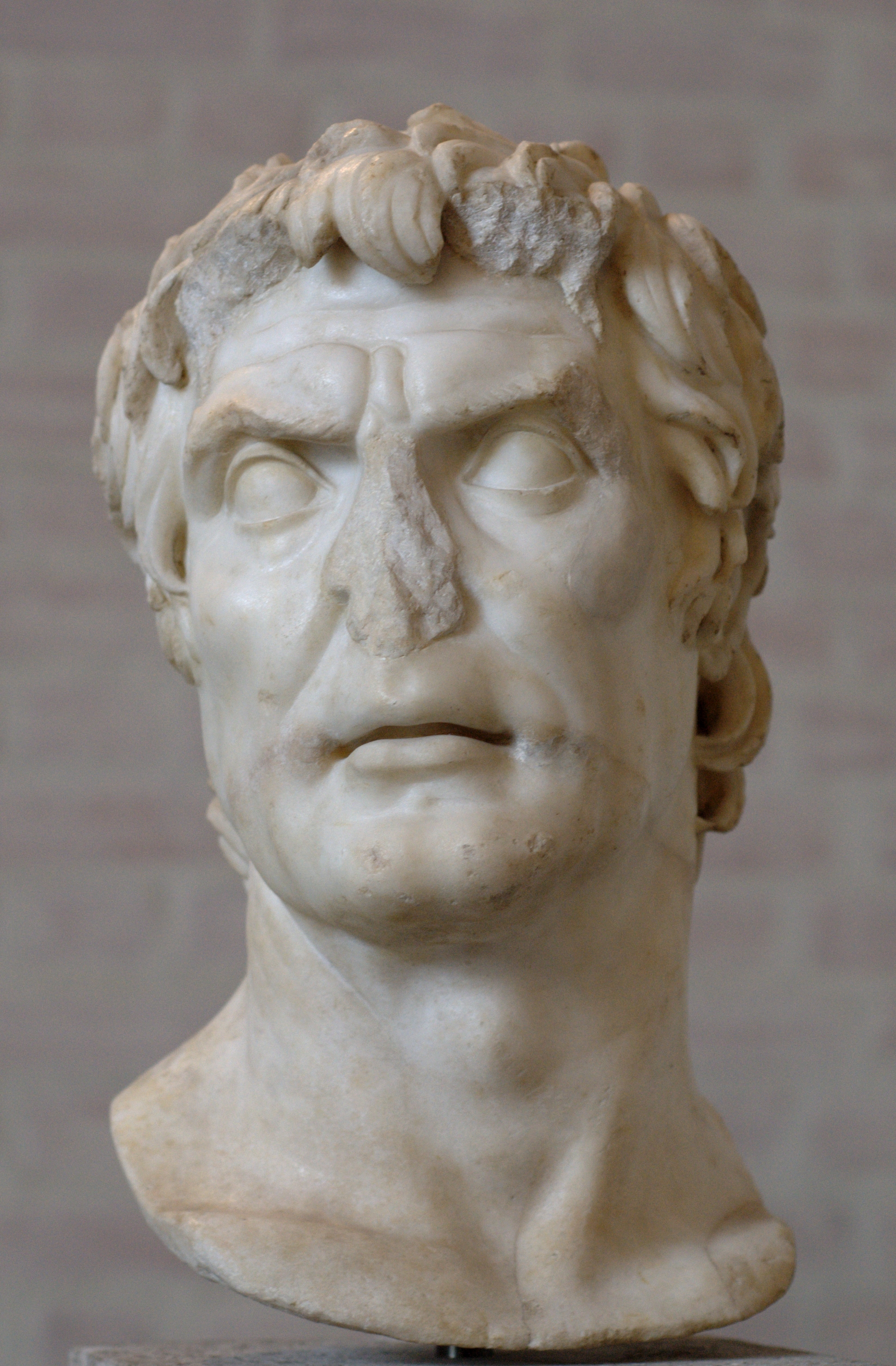

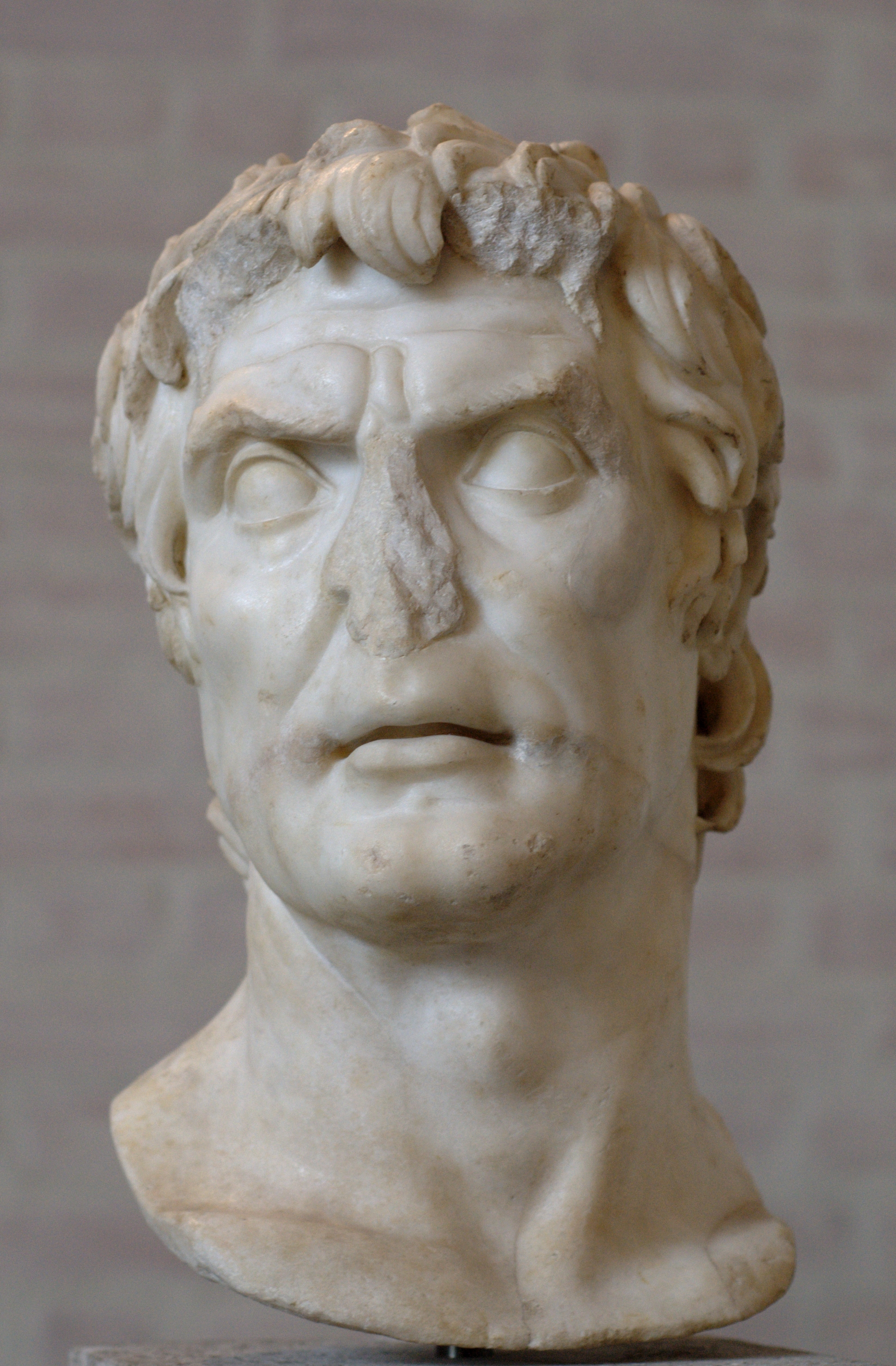

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

and the supporters of Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbrian War, Cimbric and Jugurthine War, Jugurthine wars, he held the office of Roman consul, consul an unprecedented seven times. Rising from a fami ...

.

Barry Strauss argues that the crisis really started with " The Spartacus War" in 73 BC, adding that, because the dangers were unappreciated, "Rome faced the crisis with mediocrities".

Arguments for a later start date (69 to 44 BC)

Pollio andRonald Syme

Sir Ronald Syme, (11 March 1903 – 4 September 1989) was a New Zealand-born historian and classicist. He was regarded as the greatest historian of ancient Rome since Theodor Mommsen and the most brilliant exponent of the history of the Roma ...

date the Crisis only from the time of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

in 60 BC. Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon

The Rubicon (; ; ) is a shallow river in northeastern Italy, just south of Cesena and north of Rimini. It was known as ''Fiumicino'' until 1933, when it was identified with the ancient river Rubicon, crossed by Julius Caesar in 49 BC.

The ri ...

, a river marking the northern boundary of Roman Italy, with his army in 49 BC, a flagrant violation of Roman law, has become the clichéd point of no return

The point of no return (PNR or PONR) is the point beyond which one must continue on one's current course of action because turning back is no longer possible, being too dangerous, physically difficult, or prohibitively expensive to be undertaken. ...

for the Republic, as noted in many books, including Tom Holland's '' Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic''.

Arguments for an end date (49 to 27 BC)

The end of the Crisis can likewise either be dated from theassassination of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, was assassinated on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC by a group of senators during a Roman Senate, Senate session at the Curia of Pompey, located within the Theatre of Pompey in Ancient Rome, Rome. The ...

on 15 March 44 BC, after he and Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

had done so much "to dismantle the government of the Republic", or alternately when Octavian

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

was granted the title of ''Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

'' by the Senate in 27 BC, marking the beginning of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.Flower, p. 366. The end could also be dated ''earlier'', to the time of the constitutional reforms of Julius Caesar in 49 BC.

History

After the

After the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For ...

, there was a great increase in income inequality. While the landed peasantry was drafted to serve in increasingly long campaigns, their farms and homesteads fell into bankruptcy. Significant mineral wealth was distributed unevenly to the population; the city of Rome itself expanded considerably in opulence and size; the freeing of slaves brought to Italy by conquest massively expanded the number of urban and rural poor. The republic, for reasons still debated by historians, in 177 BC also stopped regularly establishing Roman colonies in Italy. One of the major functions of these colonies was to provide land for the urban and rural poor, increasing the draft pool of landed farmers as well as providing economic opportunities to the lower classes.

Political violence

The tribunate ofTiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

in 133 BC led to a breakup of the long-standing norms of the republican constitution. Gracchus was successful in passing legislation to pursue land reform, but only over a norms-breaking attempt by Marcus Octavius—a tribune in the same year as Gracchus—to veto proceedings overwhelmingly supported by the people. Gracchus' legislation would challenge the socio-political power of the old aristocracy, along with eroding their economic interests. The initial extra-constitutional actions by Octavius caused Gracchus to take similarly novel norms-breaking actions, that would lead even greater breakdowns in republican norms. The backlash against Tiberius Gracchus' attempt to secure for himself a second term as tribune of the plebs would lead to his assassination by the then- pontifex maximus Scipio Nasica, acting in his role as a private citizen and against the advice of the consul and jurist Publius Mucius Scaevola.

The Senate's violent reaction also served to legitimise the use of violence for political ends. Political violence showed fundamentally that the traditional republican norms that had produced the stability of the middle republic were incapable of resolving conflicts between political actors. As well as inciting revenge killing for previous killings, the repeated episodes also showed the inability of the existing political system to solve pressing matters of the day. The political violence also further divided citizens with different political views and set a precedent that senators—even those without lawful executive authority—could use force to silence citizens merely for holding certain political beliefs.

Tiberius Gracchus' younger brother Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus ( – 121 BC) was a reformist Roman politician and soldier who lived during the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, i ...

, who later was to win repeated office to the tribunate so to pass similarly expansive reforms, would be killed by similar violence. Consul Lucius Opimius was empowered by the senate to use military force (including a number of foreign mercenaries from Crete) in a state of emergency declared so to kill Gaius Gracchus, Marcus Fulvius Flaccus and followers. While the citizens killed in the political violence were not declared enemies, it showed clearly that the aristocracy believed violence was a "logical and more effective alternative to political engagement, negotiation, and compromise within the parameters set by existing norms".

Further political violence emerged in the sixth consulship of Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbrian War, Cimbric and Jugurthine War, Jugurthine wars, he held the office of Roman consul, consul an unprecedented seven times. Rising from a fami ...

, a famous general, known to us as 100 BC. Marius had been consul consecutively for some years by this point, owing to the immediacy of the Cimbrian War

The Cimbrian or Cimbric War (113–101 BC) was fought between the Roman Republic and the Germanic peoples, Germanic and Celts, Celtic tribes of the Cimbri and the Teutons, Ambrones and Tigurini, who migrated from the Jutland peninsula into Roma ...

. These consecutive consulships violated Roman law, which mandated a decade between consulships, further weakening the primarily norms-based constitution. Returning to 100 BC, large numbers of armed gangs—perhaps better described as militias—engaged in street violence. A candidate for high office, Gaius Memmius, was also assassinated. Marius was called upon as consul to suppress the violence, which he did, with significant effort and military force. His landless legionaries also affected voting directly, as while they could not vote themselves for failing to meet property qualifications, they could intimidate those who could.

Sulla's civil war

Following the Social War—which had the character of a civil war between Rome's Italian allies and loyalists—which was only resolved by Rome granting citizenship to almost all Italian communities, the main question looming before the state was how the Italians could be integrated into the Roman political system. TribunePublius Sulpicius Rufus

Publius Sulpicius Rufus (124–88 BC) was a Roman politician and orator whose attempts to pass controversial laws with the help of mob violence helped trigger the first civil war of the Roman Republic. His actions kindled the deadly rivalry betwe ...

in 88 BC attempted to pass legislation granting greater political rights to the Italians; one of the additions to this legislative programme included a transfer of command of the coming First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War /ˌmɪθrəˈdædɪk/ (89–85 BC) was a war challenging the Roman Republic's expanding empire and rule over the Greek world. In this conflict, the Kingdom of Pontus and many Greek cities rebelling against Roman rule ...

from Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

to Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbrian War, Cimbric and Jugurthine War, Jugurthine wars, he held the office of Roman consul, consul an unprecedented seven times. Rising from a fami ...

, who had re-entered politics. Flower writes, "by agreeing to promote the career of Marius, Sulpicius ... decided to throw republican norms aside in his bid to control the political scene in Rome and get his reforms" passed.

The attempts to recall Sulla led to his then-unprecedented and utterly unanticipated marching on Rome with his army encamped at Nola (near Naples). This choice collapsed any republican norms about the use of force. In this first (he would invade again) march on Rome, he declared a number of his political opponents enemies of the state and ordered their murder. Marius would escape to his friendly legionary colonies in Africa. Sulpicius was killed. He also installed two new consuls and forced major reforms of the constitution at sword-point, before leaving on campaign against Mithridates.

While Sulla was fighting Mithridates, Lucius Cornelius Cinna

Lucius Cornelius Cinna (before 130 BC – early 84 BC) was a four-time consul of the Roman republic. Opposing Sulla's march on Rome in 88 BC, he was elected to the consulship of 87 BC, during which he engaged in an armed conf ...

dominated domestic Roman politics, controlling elections and other parts of civil life. Cinna and his partisans were no friends of Sulla: they razed Sulla's house in Rome, revoked his command in name, and forced his family to flee the city. Cinna himself would win election to the consulship three times consecutively; he also conducted a purge of his political opponents, displaying their heads on the rostra in the forum. During the war, Rome fielded two armies against Mithridates: one under Sulla and another, fighting both Sulla and Mithridates. Sulla returned in 82 BC at the head of his army, after concluding a generous peace with Mithridates, to retake the city from the domination of the Cinnan faction. After winning a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

and purging the republic of thousands of political opponents and "enemies" (many of whom were targeted for their wealth), he forced the Assemblies to make him dictator for the settling of the constitution, with an indefinite term. Sulla also created legal barriers, which would only be lifted during the dictatorship of Julius Caesar some forty years later, against political participation by the relatives of those whom he ordered murdered. And with this use of unprecedented violence at a new level, Sulla was able not only to take control of the state, but also retain control, unlike Scipio Nasica or Gaius Marius, both of whom quickly lost their influence after deploying force.

Sulla's dictatorship ended the middle republic's culture of consensus-based senatorial decision-making by purging many of those men who lived by and reproduced that culture. Generally, Sulla's dictatorial reforms attempted to concentrate political power into the Senate and the aristocratic assemblies, whilst trying to reduce the obstructive and legislative powers of the tribune and plebeian council. To this end, he required that all bills presented to the Assemblies first be approved by the Senate, restricted the tribunician veto to only matters of individual requests for clemency, and required that men elected tribune would be barred from all other magistracies. Beyond stripping the tribunate of its powers, the last provision was intended to prevent ambitious youth from seeking the office, by making it a dead end.

Sulla also permanently enlarged the senate by promoting a large number of equestrians from the Italian countryside as well as automatically inducting the now-20 quaestors elected each year into the senate. The senatorial class was so enlarged to staff newly created permanent courts. These reforms were an attempt to formalise and strengthen the legal system so prevent political players from emerging with too much power, as well as to make them accountable to the enlarged senatorial class.

He also rigidly formalised the ''cursus honorum

The , or more colloquially 'ladder of offices'; ) was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The comprised a mixture of ...

'' by clearly stating the progression of office and associated age requirements. Next, to aid administration, he doubled the number of quaestors to 20 and added two more praetors; the greater number of magistrates also meant he could shorten the length of provincial assignments (and lessen the chances of building provincial power bases) by increasing the rate of turnover. Moreover, magistrates were barred from seeking reelection to any post for ten years and barred for two years from holding any other post after their term ended.

After securing election as consul in 80 BC, Sulla resigned the dictatorship and attempted to solidify his republican constitutional reforms. Sulla's reforms proved unworkable. The first years of Sulla's new republic were faced not only the continuation of the civil war against Quintus Sertorius

Quintus Sertorius ( – 73 or 72 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who led a large-scale rebellion against the Roman Senate on the Iberian Peninsula. Defying the regime of Sulla, Sertorius became the independent ruler of Hispania for m ...

in Spain, but also a revolt in 78 BC by the then-consul Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. With significant popular unrest, the tribunate's powers were quickly restored by 70 BC by Sulla's own lieutenants': Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

and Crassus. Sulla passed legislation to make it illegal to march on Rome as he had, but having just shown that doing so would bring no personal harm so long as one was victorious, this obviously had little effect. Sulla's actions and civil war fundamentally weakened the authority of the constitution and created a clear precedent that an ambitious general could make an end-run around the entire republican constitution simply by force of arms. The stronger law courts created by Sulla, along with reforms to provincial administration that forced consuls to stay in the city for the duration of their terms (rather than running to their provincial commands upon election), also weakened the republic: the stringent punishments of the courts helped to destabilise, as commanders would rather start civil wars than subject themselves to them, and the presence of both consuls in the city increased chances of deadlock. Many Romans also followed Sulla's example and turned down provincial commands, concentrating military experience and glory into an even smaller circle of leading generals.

Collapse of the republic

Over the course of the late republic, formerly authoritative institutions lost their credibility and authority. For example, the Sullan reforms to the Senate strongly split the aristocratic class between those who stayed in the city and those who rose to high office abroad, further increasing class divides between Romans, even at the highest levels. Furthermore, the dominance of the military in the late republic, along with stronger ties between a general and his troops, caused by their longer terms of service together and the troops' reliance on that general to provide for their retirements, along with an obstructionist central government, made a huge number of malcontent soldiers willing to take up arms against the state. Adding in the institutionalisation of violence as a means to obstruct or force political change (eg the deaths of the Gracchi and Sulla's dictatorship, respectively), the republic was caught in an ever more violent and anarchic struggle between the Senate, assemblies at Rome, and the promagistrates. Even by the early-60s BC, political violence began to reassert itself, with unrest at the consular elections noted at every year between 66 and 63. The revolt of Catiline—which we hear much about from the consul for that year,Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

—was put down by violating the due process rights of citizens and introducing the death penalty to the Roman government's relationship with its citizens. The anarchy of republican politics since the Sullan reforms had done nothing to address agrarian reform, the civic disabilities of proscribed families, or intense factionalism between Marian and Sullan supporters. Through this whole period, Pompey's extraordinary multi-year commands in the east made him wealthy and powerful; his return in 62 BC could not be handled within the context of a republican system: his achievements were not recognised but nor could he be dispatched away from the city to win more victories. His extraordinary position created a "volatile situation that the senate and the magistrates at home could not control". Both Cicero's actions during his consulship and Pompey's great military successes challenged the republic's legal codes that were meant to restrain ambition and defer punishments to the courts.

The domination of the state by the three-man group of the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Gaius Julius Caesar. The republican constitution had many veto points. ...

—Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

—from 59 BC did little to restore order or peace in Rome. The first "triumvirate" dominated republican politics by controlling elections, continually holding office, and violating the law through their long periods of ''ex officio'' political immunity. This political authority so dominated other magistrates that they were unwilling to oppose their policies or voice opposition. Political violence both became more acute and chaotic: the total anarchy that emerged in the mid-50s by duelling street gangs under the control of Publius Clodius Pulcher

Publius Clodius Pulcher ( – 18 January 52 BC) was a Roman politician and demagogue. A noted opponent of Cicero, he was responsible during his plebeian tribunate in 58 BC for a massive expansion of the Roman grain dole as well as Cic ...

and Titus Annius Milo

Titus Annius Milo (died 48 BC) was a Roman politician and agitator. The son of Gaius Papius Celsus, he was adopted by his maternal grandfather, Titus Annius Luscus. In 52 BC, he was prosecuted for the murder of Publius Clodius Pulcher and exile ...

prevented orderly consular elections repeatedly in the 50s.

The destruction of the senate house and escalation of violence continued until Pompey was simply appointed by the senate, without consultation of the assemblies, as sole consul in 52 BC. The domination of the city by Pompey and repeated political irregularities led to Caesar being unwilling to subject himself to what he considered to be biased courts and unfairly administered laws, starting Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

.

Whether the period starting with Caesar's civil war should really be called a portion of the republic is a matter of scholarly debate. After Caesar's victory, he ruled a dictatorial regime until his assassination in 44 BC at the hands of the Liberatores

Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, was assassinated on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC by a group of senators during a Senate session at the Curia of Pompey, located within the Theatre of Pompey in Rome. The conspirators, numbering ...

. The Caesarian faction quickly gained control of the state, inaugurated the Second Triumvirate

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created at the end of the Roman republic for Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November ...

(comprising Caesar's adopted son Octavian

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

and the dictator's two most important supporters, Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus), purged their political enemies, and successfully defeated the assassins in the Liberators' civil war

The Liberators' civil war (43–42 BC) was started by the Second Triumvirate to avenge Julius Caesar's assassination. The war was fought by the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (the Second Triumvirate members, or ''Triumvirs'') against the fo ...

at the Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Liberators' civil war between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius, in 42 BC, at Philippi in ...

. The second triumvirate failed to reach any mutually agreeable resolution; leading to the final civil war of the republic, a war which the promagistrate governors and their troops won, and in doing so, permanently collapsed the republic. Octavian, now Augustus, became the first Roman Emperor and transformed the oligarchic republic into the autocratic

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and Head of government, government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with demo ...

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.

See also

*Constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the constitution, political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variat ...

* Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis, was a period in History of Rome, Roman history during which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressure of repeated Barbarian invasions ...

* ''Damnatio memoriae

() is a modern Latin phrase meaning "condemnation of memory" or "damnation of memory", indicating that a person is to be excluded from official accounts. Depending on the extent, it can be a case of historical negationism. There are and have b ...

''

* Democratic backsliding

Democratic backsliding or autocratization is a process of regime change toward autocracy in which the exercise of political power becomes more arbitrary and repressive. The process typically restricts the space for public contest and politi ...

* Fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

Notes

References

Sources and further reading

* * * * * * * * ** ** * * * * Reprinted 2003, 2009. * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* (Schmitz and Zumpt, 1848): ''Bellum Iugurthinum'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Crisis of the Roman Republic Foreign relations of ancient Rome History of the Roman Republic Roman Republican civil wars Slavery in ancient Rome Social class in ancient Rome 2nd century BC in the Roman Republic 1st century BC in the Roman Republic Civil disorder