The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or , sk, kozáci , uk, козаки́ are a predominantly

East Slavic Orthodox Christian people originating in the

Pontic–Caspian steppe of

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

and

southern Russia. Historically, they were a semi-nomadic and semi-militarized people, who, while under the nominal

suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

of various Eastern European states at the time, were allowed a great degree of self-governance in exchange for military service. Although numerous linguistic and religious groups came together to form the Cossacks, most of them coalesced and became

East Slavic-speaking

Orthodox Christians. The Cossacks were particularly noted for holding democratic traditions. The rulers of the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

endowed Cossacks with certain special privileges in return for the military duty to serve in the irregular troops (mostly cavalry). The various Cossack groups were organized along military lines, with large autonomous groups called

hosts

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

*Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

*Michel Host ...

. Each host had a territory consisting of affiliated villages called

stanitsa.

They inhabited sparsely populated areas in the

Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

,

Don,

Terek, and

Ural river basins, and played an important role in the historical and cultural development of both Russia and Ukraine.

The Cossack way of life persisted into the twentieth century, though the sweeping societal changes of the

Russian Revolution disrupted Cossack society as much as any other part of Russia; many Cossacks migrated to other parts of Europe following the establishment of the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, while others remained and assimilated into the Communist state. Cohesive Cossack-based units were organized and many fought for both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

After World War II, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

disbanded the Cossack units in the

Soviet Army

uk, Радянська армія

, image = File:Communist star with golden border and red rims.svg

, alt =

, caption = Emblem of the Soviet Army

, start_date ...

, and many of the Cossack traditions were suppressed during the years of rule under Joseph Stalin and his successors. During the

Perestroika era in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, descendants of Cossacks moved to revive their national traditions. In 1988, the Soviet Union passed a law allowing the re-establishment of former

Cossack hosts and the formation of new ones. During the 1990s, many regional authorities agreed to hand over some local administrative and policing duties to their Cossack hosts.

Between 3.5 and 5 million people associate themselves with the Cossack

cultural identity across the world.

Cossack organizations operate in

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

,

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

,

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

,

Kazakhstan,

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

Etymology

Max Vasmer

Max Vasmer's etymological dictionary traces the name to the

Old East Slavic word , , a loanword from

Cuman

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many sough ...

, in which ''cosac'' meant "free man" but also "conqueror". The ethnonym

Kazakh is from the same

Turkic root.

In written sources, the name is first attested in the ''

Codex Cumanicus'' from the 13th century. In

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, "Cossack" is first attested in 1590.

[

]

Early history

It is unclear when people other than the Brodnici and

It is unclear when people other than the Brodnici and Berladnici

The Berladnici ( pl, Berładnicy; ro, Berladnici; russian: Берладники; uk, Берладники) were a supposed medieval people living along the northeastern Black Sea coast. While their ethnicity is unclear, it included runaways from ...

(which had a Romanian origin with large Slavic influences) began to settle in the lower reaches of major rivers such as the Don and the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

after the demise of the Khazar state. Their arrival was probably not before the 13th century, when the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

broke the power of the Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many so ...

, who had assimilated the previous population on that territory. It is known that new settlers inherited a lifestyle that long pre-dated their presence, including that of the Turkic Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many so ...

and the Circassian Kassaks.Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

in the 13th century as the influence of Cumans grew weaker, although some have ascribed their origins to as early as the mid-8th century.[Vasili Glazkov (Wasili Glaskow), ''History of the Cossacks'', p. 3, Robert Speller & Sons, New York, Vasili Glazkov claims that the data of ]Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

ian and Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

historians support that. According to this view, by 1261, Cossacks lived in the area between the rivers Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and t ...

and Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

as described for the first time in Russian chronicles. Some historians suggest that the Cossack people were of mixed ethnic origin, descending from East Slavs

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert ...

, Turks, Tatar

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different s, and others who settled or passed through the vast Steppe.Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many so ...

of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, who had lived there long before the Mongol invasion.Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

and Lithuania grew in power, new political entities appeared in the region. These included Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

and the Crimean Khanate. In 1261, Slavic people living in the area between the Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and t ...

and the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

were mentioned in Ruthenian chronicles. Historical records of the Cossacks before the 16th century are scant, as is the history of the Ukrainian lands in that period.

As early as the 15th century, a few individuals ventured into the Wild Fields, the southern frontier regions of Ukraine separating Poland-Lithuania from the Crimean Khanate. These were short-term expeditions, to acquire the resources of what was a naturally rich and fertile region teeming with cattle, wild animals, and fish. This lifestyle, based on subsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow food crops to meet the needs of themselves and their families on smallholdings. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements, with little or no ...

, hunting, and either returning home in the winter or settling permanently, came to be known as the Cossack way of life. The Crimean–Nogai raids into East Slavic lands caused considerable devastation and depopulation in this area. The Tatar raids also played an important role in the development of the Cossacks.

In the 15th century, Cossack society was described as a loose

In the 15th century, Cossack society was described as a loose federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

of independent communities, which often formed local armies and were entirely independent from neighboring states such as Poland, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, and the Crimean Khanate. According to Hrushevsky, the first mention of Cossacks dates back to the 14th century, although the reference was to people who were either Turkic or of undefined origin. Hrushevsky states that the Cossacks may have descended from the long-forgotten Antes, or from groups from the Berlad territory of the Brodniki in present-day Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, then a part of the Grand Duchy of Halych. There, the Cossacks may have served as self-defense formations, organized to defend against raids conducted by neighbors. By 1492, the Crimean Khan complained that Kanev and Cherkasy Cossacks had attacked his ship near Tighina

Bender (, Moldovan Cyrillic: Бендер) or Bendery (russian: Бендеры, , uk, Бендери), also known as Tighina ( ro, Tighina), is a city within the internationally recognized borders of Moldova under ''de facto'' control of the un ...

(Bender), and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of A ...

promised to find the guilty party. Sometime in the 16th century, there appeared the old Ukrainian ''Ballad of Cossack Holota'', about a Cossack near Kiliya.

In the 16th century, these Cossack societies merged into two independent territorial organizations, as well as other smaller, still-detached groups:

* The Cossacks of Zaporizhzhia, centered on the lower bends of the Dnieper, in the territory of modern Ukraine, with the fortified capital of Zaporozhian Sich. They were given significant autonomous privileges, operating as an autonomous state (the Zaporozhian Host) within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, by a treaty with Poland in 1649.

*The Don Cossack State, on the River Don. Its capital was initially Razdory, then it was moved to Cherkassk

Starocherkasskaya (russian: Старочерка́сская), formerly Cherkassk (), is a rural locality (a '' stanitsa'') in Aksaysky District of Rostov Oblast, Russia, with origins dating from the late 16th century. It is located on the righ ...

, and later to Novocherkassk

Novocherkassk (russian: Новочерка́сск, lit. ''New Cherkassk'') is a city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, located near the confluence of the Tuzlov and Aksay Rivers, the latter a distributary of the Don River. Novocherkassk is best known as ...

.

There are also references to the less well-known Tatar

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Cossacks, including the Nağaybäklär and Meschera (mishari) Cossacks, of whom Sary Azman was the first Don ataman. These groups were assimilated by the Don Cossacks, but had their own irregular Bashkir and Meschera Host up to the end of the 19th century. The Kalmyk and Buryat Cossacks also deserve mention.

Later history

The origins of the Cossacks are disputed. Originally, the term referred to semi-independent Tatar groups ('' qazaq'' or "free men") who inhabited the Pontic–Caspian steppe, north of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

near the Dnieper River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

. By the end of the 15th century, the term was also applied to peasants who had fled to the devastated regions along the Dnieper and Don Rivers, where they established their self-governing communities. Until at least the 1630s, these Cossack groups remained ethnically and religiously open to virtually anybody, although the Slavic element predominated. There were several major Cossack hosts in the 16th century: near the Dnieper, Don, Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

and Ural Rivers; the Greben Cossacks

The Grebensky Cossacks or Grebentsy was a group of Cossacks formed in the 16th century from Don Cossacks who left the Don area and settled in the northern foothills of the Caucasus. The Greben Cossacks are part of the Terek Cossacks. They were i ...

in Caucasia; and the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

, mainly west of the Dnieper.Sich

A sich ( uk, січ), or sech, was an administrative and military centre of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The word ''sich'' derives from the Ukrainian verb сікти ''siktý'', "to chop" – with the implication of clearing a forest for an encampme ...

became a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

polity of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

during feudal times. Under increasing pressure from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the mid-17th century the Sich declared an independent Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate ( uk, Гетьманщина, Hetmanshchyna; or ''Cossack state''), officially the Zaporizhian Host or Army of Zaporizhia ( uk, Військо Запорозьке, Viisko Zaporozke, links=no; la, Exercitus Zaporoviensis) ...

. The Hetmanate was initiated by a rebellion under Bohdan Khmelnytsky against Polish and Catholic domination, known as the Khmelnytsky Uprising. Afterwards, the Treaty of Pereyaslav (1654) brought most of the Cossack state under Russian rule. The Sich, with its lands, became an autonomous region under the Russian protectorate.

The Don Cossack Army, an autonomous military state formation of the Don Cossacks under the citizenship of the Moscow State in the Don region in 1671–1786, began a systematic conquest and colonization of lands to secure the borders on the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

, the whole of Siberia (see Yermak Timofeyevich), and the Yaik (Ural) and Terek Rivers. Cossack communities had developed along the latter two rivers well before the arrival of the Don Cossacks.

By the 18th century, Cossack hosts in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

occupied effective buffer zones on its borders. The expansionist ambitions of the Empire relied on ensuring Cossack loyalty, which caused tension given their traditional exercise of freedom, democracy, self-rule, and independence. Cossacks such as Stenka Razin

Stepan Timofeyevich Razin (russian: Степа́н Тимофе́евич Ра́зин, ; 1630 – ), known as Stenka Razin ( ), was a Cossack leader who led a major uprising against the nobility and tsarist bureaucracy in southern Russia in 16 ...

, Kondraty Bulavin

The Bulavin Rebellion or Astrakhan Revolt (; Восстание Булавина, ''Vosstaniye Bulavina'') was a war which took place in the years 1707 and 1708 between the Don Cossacks and the Tsardom of Russia. Kondraty Bulavin, a democratical ...

, Ivan Mazepa and Yemelyan Pugachev led major anti-imperial wars and revolutions in the Empire in order to abolish slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and harsh bureaucracy, and to maintain independence. The Empire responded with executions and tortures, the destruction of the western part of the Don Cossack Host during the Bulavin Rebellion in 1707–1708, the destruction of Baturyn after Mazepa's rebellion in 1708, and the formal dissolution of the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Host after Pugachev's Rebellion in 1775. After the Pugachev rebellion, the Empire renamed the Yaik Host, its capital, the Yaik Cossacks, and the Cossack town of Zimoveyskaya in the Don region to try to encourage the Cossacks to forget the men and their uprisings. It also formally dissolved the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Cossack Host, and destroyed their fortress on the Dnieper (the Sich itself). This may in part have been due to the participation of some Zaporozhian and other Ukrainian exiles in Pugachev's rebellion. During his campaign, Pugachev issued manifestos calling for restoration of all borders and freedoms of both the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Lower Dnieper (Nyzovyi in Ukrainian) Cossack Host under the joint protectorate of Russia and the Commonwealth.

By the end of the 18th century, Cossack nations had been transformed into a special military estate ( ''sosloviye''), "a military class". The Malorussian Cossacks (the former "Registered Cossacks" Town Zaporozhian Host" in Russia were excluded from this transformation, but were promoted to membership of various civil estates or classes (often Russian nobility), including the newly created civil estate of Cossacks. Similar to the knights of medieval Europe in feudal times, or to the tribal Roman auxiliaries, the Cossacks had to obtain their cavalry horses, arms, and supplies for their military service at their own expense, the government providing only firearms and supplies. Lacking horses, the poor served in the Cossack infantry and artillery. In the navy alone, Cossacks served with other peoples as the Russian navy had no Cossack ships and units. Cossack service was considered rigorous.

Cossack forces played an important role in Russia's wars of the 18th–20th centuries, including the Great Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swe ...

, the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

, the Caucasus War, many Russo-Persian Wars, many Russo-Turkish Wars, and the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Tsarist regime used Cossacks extensively to perform police service. Cossacks also served as border guards on national and internal ethnic borders, as had been the case in the Caucasus War.

During the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, Don and Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks (russian: кубанские казаки, ''kubanskiye kаzaki''; uk, кубанські козаки, ''kubanski kozaky''), or Kubanians (russian: кубанцы, ; uk, кубанці, ), are Cossacks who live in the Kuban r ...

were the first people to declare open war against the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. In 1918, Russian Cossacks declared their complete independence, creating two independent states: the Don Republic and the Kuban People's Republic, and the Ukrainian State emerged. Cossack troops formed the effective core of the anti-Bolshevik White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

, and Cossack republics became centers for the anti-Bolshevik White movement. With the victory of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, Cossack lands were subjected to decossackization and the Holodomor famine. As a result, during the Second World War, their loyalties were divided and both sides had Cossacks fighting in their ranks.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Cossacks made a systematic return to Russia. Many took an active part in post-Soviet conflicts

This article lists the post-Soviet conflicts; the violent political and ethnic conflicts in the countries of the former Soviet Union following its dissolution in 1991.

Some of these conflicts such as the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis or ...

. In the 2002 Russian Census, 140,028 people reported their ethnicity as Cossack. There are Cossack organizations in Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

Ukrainian Cossacks

Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks lived on the Pontic–Caspian steppe below the

The Zaporozhian Cossacks lived on the Pontic–Caspian steppe below the Dnieper Rapids

The Dnieper Rapids ( uk, Дніпрові пороги, ) are the historical rapids on the Dnieper river in Ukraine, composed of outcrops of granites, gneisses and other types of bedrock of the Ukrainian Shield. The rapids began below the present ...

(Ukrainian: ''za porohamy''), also known as the Wild Fields. The group became well known, and its numbers increased greatly between the 15th and 17th centuries. The Zaporozhian Cossacks played an important role in European geopolitics, participating in a series of conflicts and alliances with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

.

The Zaporozhians gained a reputation for their raids against the Ottoman Empire and its vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

s, although they also sometimes plundered other neighbors. Their actions increased tension along the southern border of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Low-level warfare took place in those territories for most of the period of the Commonwealth (1569–1795).

Prior to the formation of the Zaporizhian Sich, Cossacks had usually been organized by Ruthenian boyars, or princes of the nobility, especially various Lithuanian starostas. Merchants, peasants, and runaways from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Muscovy, and Moldavia also joined the Cossacks.

The first recorded Zaporizhian Host prototype was formed by the starosta of Cherkasy and Kaniv

Kaniv ( uk, Канів, ) city located in Cherkasy Raion, Cherkasy Oblast ( province) in central Ukraine. The city rests on the Dnieper River, and is also one of the main inland river ports on the Dnieper. It hosts the administration of Kaniv ...

, Dmytro Vyshnevetsky, who built a fortress on the island of Little Khortytsia on the banks of the Lower Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

in 1552. The Zaporizhian Host adopted a lifestyle that combined the ancient Cossack order and habits with those of the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

.

The Cossack structure arose, in part, in response to the struggle against Tatar raids. Socio-economic developments in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were another important factor in the growth of the Ukrainian Cossacks. During the 16th century, serfdom was imposed because of the favorable conditions for grain sales in Western Europe. This subsequently decreased the locals' land allotments and freedom of movement. In addition, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth government attempted to impose Catholicism, and to Polonize the local Ukrainian population. The basic form of resistance and opposition by the locals and burghers was flight and settlement in the sparsely populated steppe.Severyn Nalyvaiko

Severyn (Semeriy) Nalyvaiko (, , in older historiography also ''Semen Nalewajko'', died 21 April 1597) was a leader of the Ukrainian Cossacks who became a hero of Ukrainian folklore. He led the failed Nalyvaiko Uprising for which he was tortur ...

(1594–1596), Hryhorii Loboda (1596), Marko Zhmailo (1625), Taras Fedorovych

Taras Fedorovych ( pseudonym, Taras Triasylo, Hassan Tarasa, Assan Trasso) ( uk, Тара́с Федоро́вич, pl, Taras Fedorowicz) (died after 1636) was a prominent leader of the Dnieper Cossacks, a popular Hetman (Cossack leader) elected ...

(1630), Ivan Sulyma (1635), Pavlo Pavliuk and Dmytro Hunia (1637), and Yakiv Ostrianyn and Karpo Skydan (1638). All were brutally suppressed and ended by the Polish government.

Foreign and external pressure on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth led to the government making concessions to the Zaporizhian Cossacks. King Stephen Báthory granted them certain rights and freedoms in 1578, and they gradually began to create their foreign policy. They did so independently of the government, and often against its interests, as for example with their role in Moldavian affairs, and with the signing of a treaty with Emperor Rudolf II in the 1590s.Livny

Livny (russian: Ливны, p=ˈlʲivnɨ) is a town in Oryol Oblast, Russia. As of 2018, it had a population of 47,221. :ru:Ливны#cite note-2018AA-3

History

The town is believed to have originated in 1586 as Ust-Livny, a wooden fort on ...

and Yelets. In September 1618, with Chodkiewicz, Konashevych-Sahaidachny laid siege to Moscow, but peace was secured.

After Ottoman-Polish and Polish-Muscovite warfare ceased, the official Cossack register was again decreased. The registered Cossacks (''reiestrovi kozaky'') were isolated from those who were excluded from the register, and from the Zaporizhian Host. This, together with intensified socioeconomic and national-religious oppression of the other classes in Ukrainian society, led to a number of Cossack uprisings in the 1630s. These eventually culminated in the Khmelnytsky Uprising, led by the hetman of the Zaporizhian Sich, Bohdan Khmelnytsky.Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate ( uk, Гетьманщина, Hetmanshchyna; or ''Cossack state''), officially the Zaporizhian Host or Army of Zaporizhia ( uk, Військо Запорозьке, Viisko Zaporozke, links=no; la, Exercitus Zaporoviensis) ...

(1649–1764). It was placed under the suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

of the Russian Tsar from 1667, but was ruled by local hetmans for a century. The principal political problem of the hetmans who followed the Pereyeslav Agreement was defending the autonomy of the Hetmanate from Russian/Muscovite centralism. The hetmans Ivan Vyhovsky, Petro Doroshenko and Ivan Mazepa attempted to resolve this by separating Ukraine from Russia.Aleksey Trubetskoy

Prince Aleksey Nikitich Trubetskoy (russian: Алексей Никитич Трубецкой; c. 17 March 1600 – 1680) was the last voivode of the Trubetskoy family and a diplomat who was active in negotiations with Poland and Sweden in 164 ...

. After terrible losses, Trubetskoy was forced to withdraw to the town of Putyvl on the other side of the border. The battle is regarded as one of the Zaporizhian Cossacks' most impressive victories.Yurii Khmelnytsky

Yurii Khmelnytsky ( uk, Юрій Хмельницький, pl, Jerzy Chmielnicki, russian: Юрий Хмельницкий) (1641 – 1685(?)), younger son of the famous Ukrainian Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky and brother of Tymofiy Khmelnytsky, was ...

was elected hetman of the Zaporizhian Host/Hetmanate, with the endorsement of Moscow and supported by common Cossacks unhappy with the conditions of the Union of Hadiach. In 1659, however, Yurii Khmelnytsky asked the Polish king for protection, leading to the period of Ukrainian history known as The Ruin.Peter I Peter I may refer to:

Religious hierarchs

* Saint Peter (c. 1 AD – c. 64–88 AD), a.k.a. Simon Peter, Simeon, or Simon, apostle of Jesus

* Pope Peter I of Alexandria (died 311), revered as a saint

* Peter I of Armenia (died 1058), Catholicos ...

ordered the sacking of the then capital of the Hetmanate, Baturyn. The city was burnt and looted, and 11,000 to 14,000 of its inhabitants were killed. The destruction of the Hetmanate's capital was a signal to Mazepa and the Hetmanate's inhabitants of severe punishment for disloyalty to the Tsar's authority. One of the Zaporizhian Sichs, the Chortomlyk Sich The Chortomlyk Sich (also Old Sich) is a Zaporozhian Sich state founded by the Cossacks led by kish otaman Fedir Lutay in the summer of 1652 on the right bank of the Chortomlyk distributary of the Dnieper near modern village of Kapulivka.

The S ...

built at the mouth of the Chortomlyk River in 1652, was also destroyed by Peter I's forces in 1709, in retribution for decision of the hetman of the Chortmylyk Sich, Kost Hordiyenko, to ally with Mazepa.

The Zaporozhian Sich had its own authorities, its own "Nizovy" Zaporozhsky Host, and its own land. In the second half of the 18th century, Russian authorities destroyed this Zaporozhian Host, and gave its lands to landlords. Some Cossacks moved to the Danube Delta region, where they formed the Danubian Sich under Ottoman rule. To prevent further defection of Cossacks, the Russian government restored the special Cossack status of the majority of Zaporozhian Cossacks. This allowed them to unite in the Host of Loyal Zaporozhians, and later to reorganize into other hosts, of which the Black Sea Host was most important. Because of land scarcity resulting from the distribution of Zaporozhian Sich lands among landlords, they eventually moved on to the Kuban region.

The majority of Danubian Sich Cossacks moved first to the Azov region in 1828, and later joined other former Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region. Groups were generally identified by faith rather than language in that period, and most descendants of Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region are bilingual, speaking both Russian and

The majority of Danubian Sich Cossacks moved first to the Azov region in 1828, and later joined other former Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region. Groups were generally identified by faith rather than language in that period, and most descendants of Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region are bilingual, speaking both Russian and Balachka

Baláchka ( uk, балачка, p=bɐˈlat͡ʃkɐ – conversation, chat) is a Ukrainian dialect spoken in the Kuban and Don regions, where Ukrainian settlers used to live. It was strongly influenced by Cossack culture.

The term is connecte ...

, the local Kuban dialect of central Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

. Their folklore is largely Ukrainian. The predominant view of ethnologists and historians is that its origins lie in the common culture dating back to the Black Sea Cossacks.

The major powers tried to exploit Cossack warmongering for their own purposes. In the 16th century, with the power of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth extending south, the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

were mostly, if tentatively, regarded by the Commonwealth as their subjects. Registered Cossacks

Registered Cossacks (, , pl, Kozacy rejestrowi) comprised special Cossack units of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth army in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Registered Cossacks became a military formation of the Commonwealth army beginnin ...

formed a part of the Commonwealth army until 1699.

Around the end of the 16th century, increasing Cossack aggression strained relations between the Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire. Cossacks had begun raiding Ottoman territories in the second part of the 16th century. The Polish government could not control them, but was held responsible as the men were nominally its subjects. In retaliation,

Around the end of the 16th century, increasing Cossack aggression strained relations between the Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire. Cossacks had begun raiding Ottoman territories in the second part of the 16th century. The Polish government could not control them, but was held responsible as the men were nominally its subjects. In retaliation, Tatars

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Turki ...

living under Ottoman rule launched raids into the Commonwealth, mostly in the southeast territories. Cossack pirates responded by raiding wealthy trading port-cities in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, as these were just two days away by boat from the mouth of the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

river. In 1615 and 1625, Cossacks razed suburbs of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, forcing the Ottoman Sultan to flee his palace. In 1637, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, joined by the Don Cossacks, captured the strategic Ottoman fortress of Azov, which guarded the Don.

Consecutive treaties between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth called for the governments to keep the Cossacks and Tatars in check, but neither enforced the treaties strongly. The Polish forced the Cossacks to burn their boats and stop raiding by sea, but the activity did not cease entirely. During this time, the Habsburg monarchy sometimes covertly hired Cossack raiders against the Ottomans, to ease pressure on their own borders. Many Cossacks and Tatars developed longstanding enmity due to the losses of their raids. The ensuing chaos and cycles of retaliation often turned the entire southeastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth border into a low-intensity war zone. It catalyzed escalation of Commonwealth–Ottoman warfare, from the Moldavian Magnate Wars

The Moldavian Magnate Wars, or Moldavian Ventures, refer to the period at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century when the magnates of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth intervened in the affairs of Moldavia, clashi ...

(1593–1617) to the Battle of Cecora (1620), and campaigns in the Polish–Ottoman War of 1633–1634.

Cossack numbers increased when the warriors were joined by peasants escaping serfdom in Russia and dependence in the Commonwealth. Attempts by the '' szlachta'' to turn the Zaporozhian Cossacks into peasants eroded the formerly strong Cossack loyalty towards the Commonwealth. The government constantly rebuffed Cossack ambitions for recognition as equal to the ''szlachta''. Plans for transforming the Polish–Lithuanian two-nation Commonwealth into a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth made little progress, due to the unpopularity among the Ruthenian ''szlachta'' of the idea of Ruthenian Cossacks being equal to them and their elite becoming members of the ''szlachta''. The Cossacks' strong historic allegiance to the

Cossack numbers increased when the warriors were joined by peasants escaping serfdom in Russia and dependence in the Commonwealth. Attempts by the '' szlachta'' to turn the Zaporozhian Cossacks into peasants eroded the formerly strong Cossack loyalty towards the Commonwealth. The government constantly rebuffed Cossack ambitions for recognition as equal to the ''szlachta''. Plans for transforming the Polish–Lithuanian two-nation Commonwealth into a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth made little progress, due to the unpopularity among the Ruthenian ''szlachta'' of the idea of Ruthenian Cossacks being equal to them and their elite becoming members of the ''szlachta''. The Cossacks' strong historic allegiance to the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

also put them at odds with officials of the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

-dominated Commonwealth. Tensions increased when Commonwealth policies turned from relative tolerance to suppression of the Eastern Orthodox Church after the Union of Brest. The Cossacks became strongly anti-Roman Catholic, an attitude that became synonymous with anti-Polish.

Registered Cossacks

The waning loyalty of the Cossacks, and the '' szlachta's'' arrogance towards them, resulted in several Cossack uprisings against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the early 17th century. Finally, the King's adamant refusal to accede to the demand to expand the Cossack Registry prompted the largest and most successful of these: the Khmelnytsky Uprising, that began in 1648. Some Cossacks, including the Polish ''szlachta'' in Ukraine, converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, divided the lands of the Ruthenian ''szlachta'', and became the Cossack ''szlachta''. The uprising was one of a series of catastrophic events for the Commonwealth, known as The Deluge, which greatly weakened the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and set the stage for its disintegration 100 years later.

Influential relatives of the Ruthenian and Lithuanian ''szlachta'' in Moscow helped to create the Russian–Polish alliance against Khmelnitsky's Cossacks, portrayed as rebels against order and against the private property of the Ruthenian Orthodox ''szlachta''. Don Cossacks' raids on Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

left Khmelnitsky without the aid of his usual Tatar allies. From the Russian perspective, the rebellion ended with the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav, in which, in order to overcome the Russian–Polish alliance against them, the Khmelnitsky Cossacks pledged their loyalty to the Russian Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

. In return, the Tsar guaranteed them his protection; recognized the Cossack '' starshyna'' (nobility), their property, and their autonomy under his rule; and freed the Cossacks from the Polish sphere of influence and the land claims of the Ruthenian ''szlachta''.["In 1651, in the face of a growing threat from Poland and forsaken by his Tatar allies, Khmelnytsky asked the tsar to incorporate Ukraine as an autonomous duchy under Russian protection ... the details of the union were negotiated in Moscow. The Cossacks were granted a large degree of autonomy, and they, as well as other social groups in Ukraine, retained all the rights and privileges they had enjoyed under Polish rule." ]

Only some of the Ruthenian ''szlachta'' of the Chernigov region, who had their origins in the Moscow state, saved their lands from division among Cossacks and became part of the Cossack ''szlachta''. After this, the Ruthenian ''szlachta'' refrained from plans to have a Moscow Tsar as king of the Commonwealth, its own Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki later becoming king. The last, ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to rebuild the Polish–Cossack alliance and create a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth was the 1658 Treaty of Hadiach. The treaty was approved by the Polish king and the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

, and by some of the Cossack ''starshyna'', including hetman

( uk, гетьман, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military ...

Ivan Vyhovsky. The treaty failed, however, because the ''starshyna'' were divided on the issue, and it had even less support among rank-and-file Cossacks.

Under Russian rule, the Cossack nation of the Zaporozhian Host was divided into two autonomous republics of the Moscow Tsardom: the Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate ( uk, Гетьманщина, Hetmanshchyna; or ''Cossack state''), officially the Zaporizhian Host or Army of Zaporizhia ( uk, Військо Запорозьке, Viisko Zaporozke, links=no; la, Exercitus Zaporoviensis) ...

, and the more independent Zaporizhia. These organisations gradually lost their autonomy, and were abolished by Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

in the late 18th century. The Hetmanate became the governorship of Little Russia

Little Russia (russian: Малороссия/Малая Россия, Malaya Rossiya/Malorossiya; uk, Малоросія/Мала Росія, Malorosiia/Mala Rosiia), also known in English as Malorussia, Little Rus' (russian: Малая Ру� ...

, and Zaporizhia was absorbed into New Russia

Novorossiya, literally "New Russia", is a historical name, used during the era of the Russian Empire for an administrative area that would later become the southern mainland of Ukraine: the region immediately north of the Black Sea and Crime ...

.

In 1775, the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Host was destroyed. Later, its high-ranking Cossack leaders were exiled to Siberia, its last chief, Petro Kalnyshevsky, becoming a prisoner of the Solovetsky Islands. The Cossacks established a new Sich in the Ottoman Empire without any involvement of the punished Cossack leaders.

Black Sea, Azov and Danubian Sich Cossacks

With the destruction of the Zaporizhian Sich, many Zaporizhian Cossacks, especially the vast majority of Old Believers and other people from Greater Russia, defected to Turkey. There they settled in the area of the

With the destruction of the Zaporizhian Sich, many Zaporizhian Cossacks, especially the vast majority of Old Believers and other people from Greater Russia, defected to Turkey. There they settled in the area of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

river, and founded a new Sich. Some of these Cossacks settled on the Tisa river in the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

, also forming a new Sich. A number of Ukrainian-speaking Eastern Orthodox Cossacks fled to territory under the control of the Ottoman Empire across the Danube, together with Cossacks of Greater Russian origin. There they formed a new host, before rejoining others in the Kuban. Many Ukrainian peasants and adventurers later joined the Danubian Sich. While Ukrainian folklore remembers the Danubian Sich, other new siches of Loyal Zaporozhians on the Bug and Dniester rivers did not achieve such fame.

The majority of Tisa and Danubian Sich Cossacks returned to Russia in 1828. They settled in the area north of the Azov Sea, becoming known as the Azov Cossacks. But the majority of Zaporizhian Cossacks, particularly the Ukrainian-speaking Eastern Orthodox, remained loyal to Russia despite Sich destruction. This group became known as the Black Sea Cossacks. Both Azov and Black Sea Cossacks were resettled to colonize the Kuban steppe

The Kuban steppe is one of the major steppes in Europe, located in southeastern Russia between the city of Rostov on Don and the Caucasus Mountains. The Kuban steppe is the historic home of the Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et ...

, a crucial foothold for Russian expansion in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

.

During the Cossack sojourn in Turkey, a new host was founded that numbered around 12,000 people by the end of 1778. Their settlement on the Russian border was approved by the Ottoman Empire after the Cossacks officially vowed to serve the sultan. Yet internal conflict, and the political manoeuvring of the Russian Empire, led to splits among the Cossacks. Some of the runaway Cossacks returned to Russia, where the Russian army used them to form new military bodies that also incorporated Greeks, Albanians and Crimean Tatars. After the Russo-Turkish war of 1787–1792, most of these Cossacks were absorbed into the Black Sea Cossack Host

Black Sea Cossack Host (russian: Черномо́рское каза́чье во́йско; uk, Чорномо́рське коза́цьке ві́йсько ), also known as Chernomoriya (russian: Черномо́рия), was a Cossack host ...

, together with Loyal Zaporozhians. The Black Sea Host moved to the Kuban steppe. Most of the remaining Cossacks who had stayed in the Danube Delta returned to Russia in 1828, creating the Azov Cossack Host

Azov Cossack Host ( uk, Азовське козацьке військо; russian: Азовское Казачье Войско) was a Cossack host that existed on the northern shore of the Sea of Azov, between 1832 and 1862.

The host was made ...

between Berdyansk

Berdiansk or Berdyansk ( uk, Бердя́нськ, translit=Berdiansk, ; russian: Бердя́нск, translit=Berdyansk ) is a port city in the Zaporizhzhia Oblast ( province) in south-eastern Ukraine. It is on the northern coast of the Sea ...

and Mariupol. In 1860, more Cossacks were resettled in the North Caucasus, and merged into the Kuban Cossack Host.

Russian Cossacks

The native land of the Cossacks is defined by a line of Russian town-fortresses located on the border with the steppe, and stretching from the middle Volga to Ryazan and

The native land of the Cossacks is defined by a line of Russian town-fortresses located on the border with the steppe, and stretching from the middle Volga to Ryazan and Tula

Tula may refer to:

Geography

Antarctica

*Tula Mountains

* Tula Point

India

* Tulā, a solar month in the traditional Indian calendar

Iran

* Tula, Iran, a village in Hormozgan Province

Italy

* Tula, Sardinia, municipality (''comune'') in the ...

, then breaking abruptly to the south and extending to the Dnieper via Pereyaslavl. This area was settled by a population of free people practicing various trades and crafts.

These people, constantly facing the Tatar

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different warriors on the steppe frontier, received the Turkic name ''Cossacks'' (''Kazaks''), which was then extended to other free people in Russia. Many Cumans

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian exonym ), were a Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many so ...

, who had assimilated Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

, retreated to the Principality of Ryazan

The Grand Duchy of Ryazan (1078–1521) was a duchy with the capital in Old Ryazan ( destroyed by the Mongol Empire in 1237), and then in Pereyaslavl Ryazansky, which later became the modern-day city of Ryazan. It originally split off from t ...

(Grand Duchy of Ryazan) after the Mongol invasion

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

. The oldest mention in the annals is of Cossacks of the Russian principality of Ryazan serving the principality in the battle against the Tatars in 1444. In the 16th century, the Cossacks (primarily of Ryazan) were grouped in military and trading communities on the open steppe, and began to migrate into the area of the Don.

Cossacks served as border guards and protectors of towns, forts, settlements, and trading posts. They performed policing functions on the frontiers, and also came to represent an integral part of the Russian army. In the 16th century, to protect the borderland area from Tatar invasions, Cossacks carried out sentry and patrol duties, guarding against Crimean Tatars and nomads of the Nogai Horde in the

Cossacks served as border guards and protectors of towns, forts, settlements, and trading posts. They performed policing functions on the frontiers, and also came to represent an integral part of the Russian army. In the 16th century, to protect the borderland area from Tatar invasions, Cossacks carried out sentry and patrol duties, guarding against Crimean Tatars and nomads of the Nogai Horde in the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate gras ...

region.

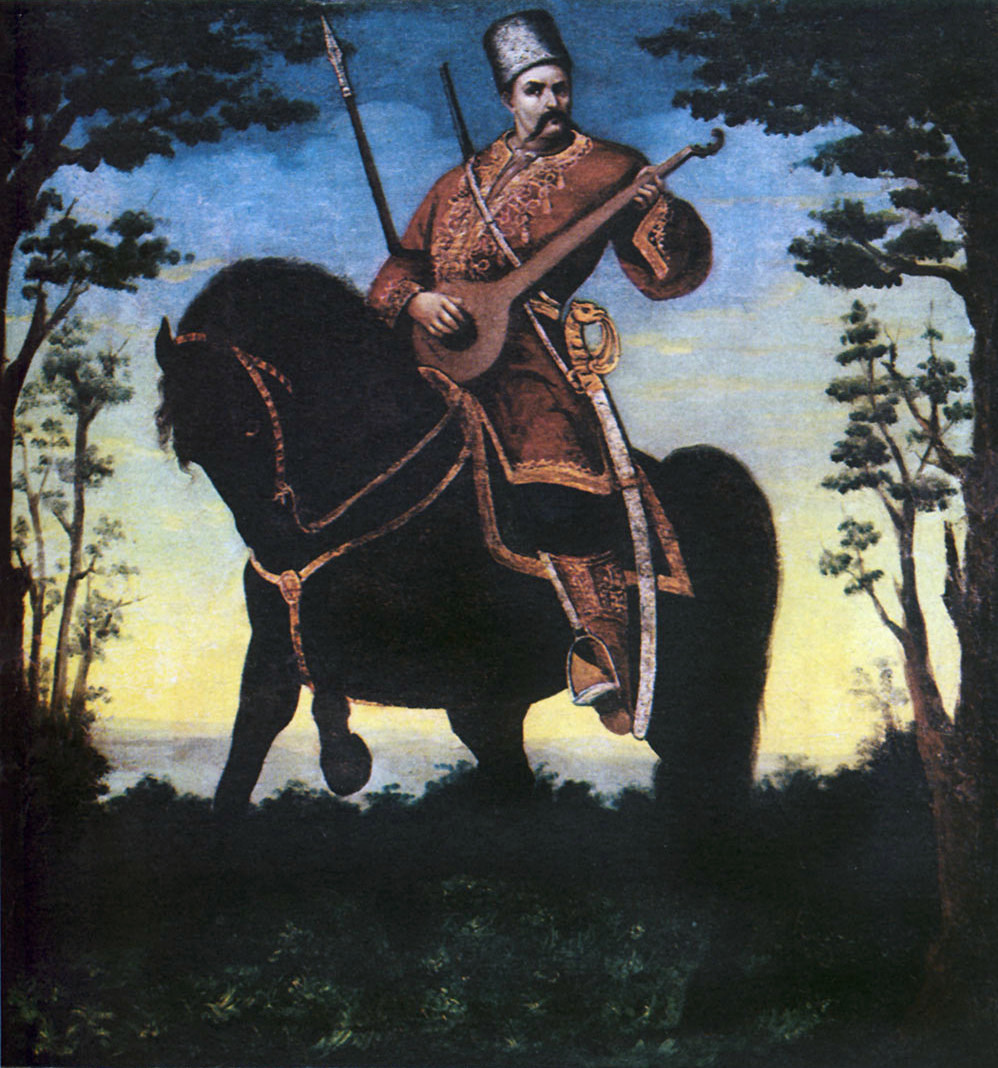

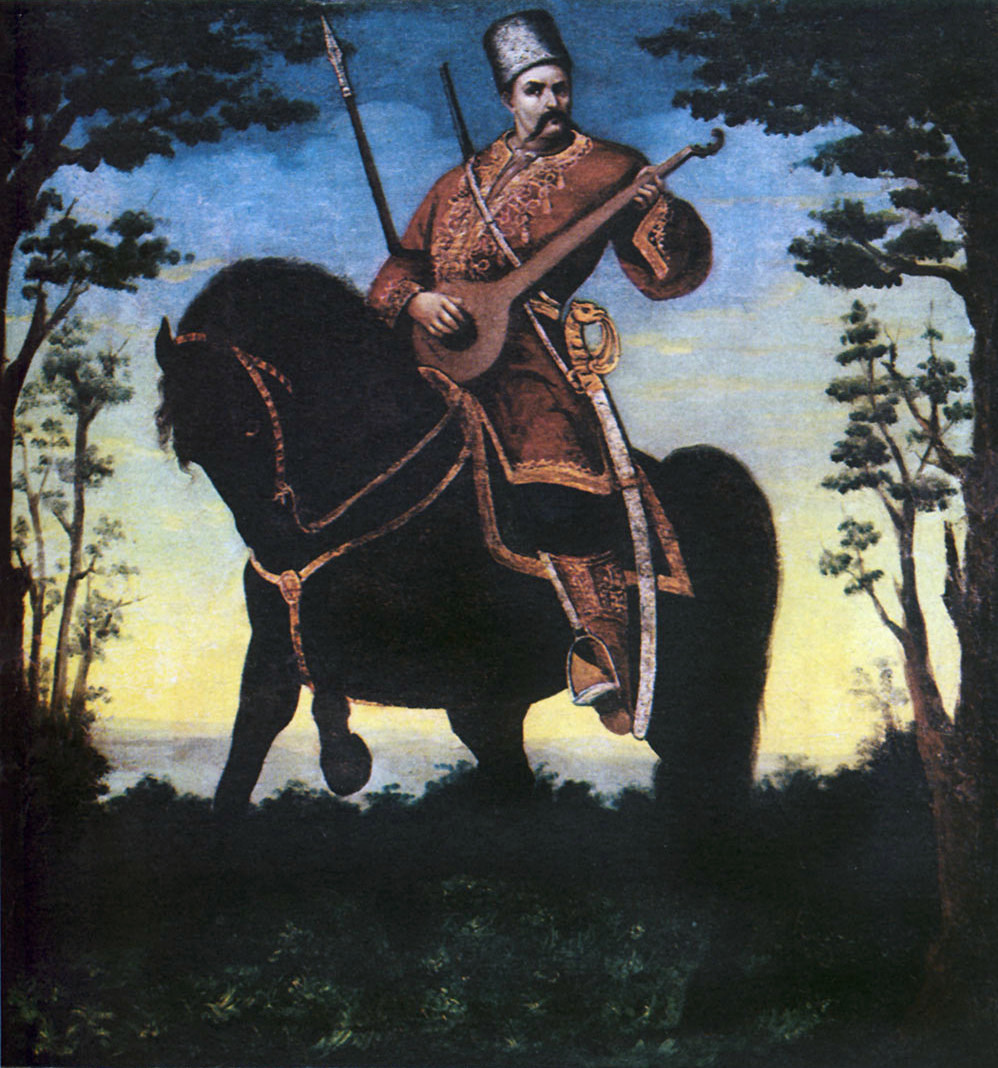

The most popular weapons of the Cossack cavalrymen were the sabre

A sabre (French: �sabʁ or saber in American English) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the early modern and Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such as t ...

, or '' shashka'', and the long spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastene ...

.

From the 16th to 19th centuries, Russian Cossacks played a key role in the expansion of the Russian Empire into Siberia (particularly by Yermak Timofeyevich), the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Cossacks also served as guides to most Russian expeditions of civil and military geographers and surveyors, traders, and explorers. In 1648, the Russian Cossack Semyon Dezhnyov discovered a passage between North America and Asia. Cossack units played a role in many wars in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, including the Russo-Turkish Wars, the Russo-Persian Wars, and the annexation of Central Asia.

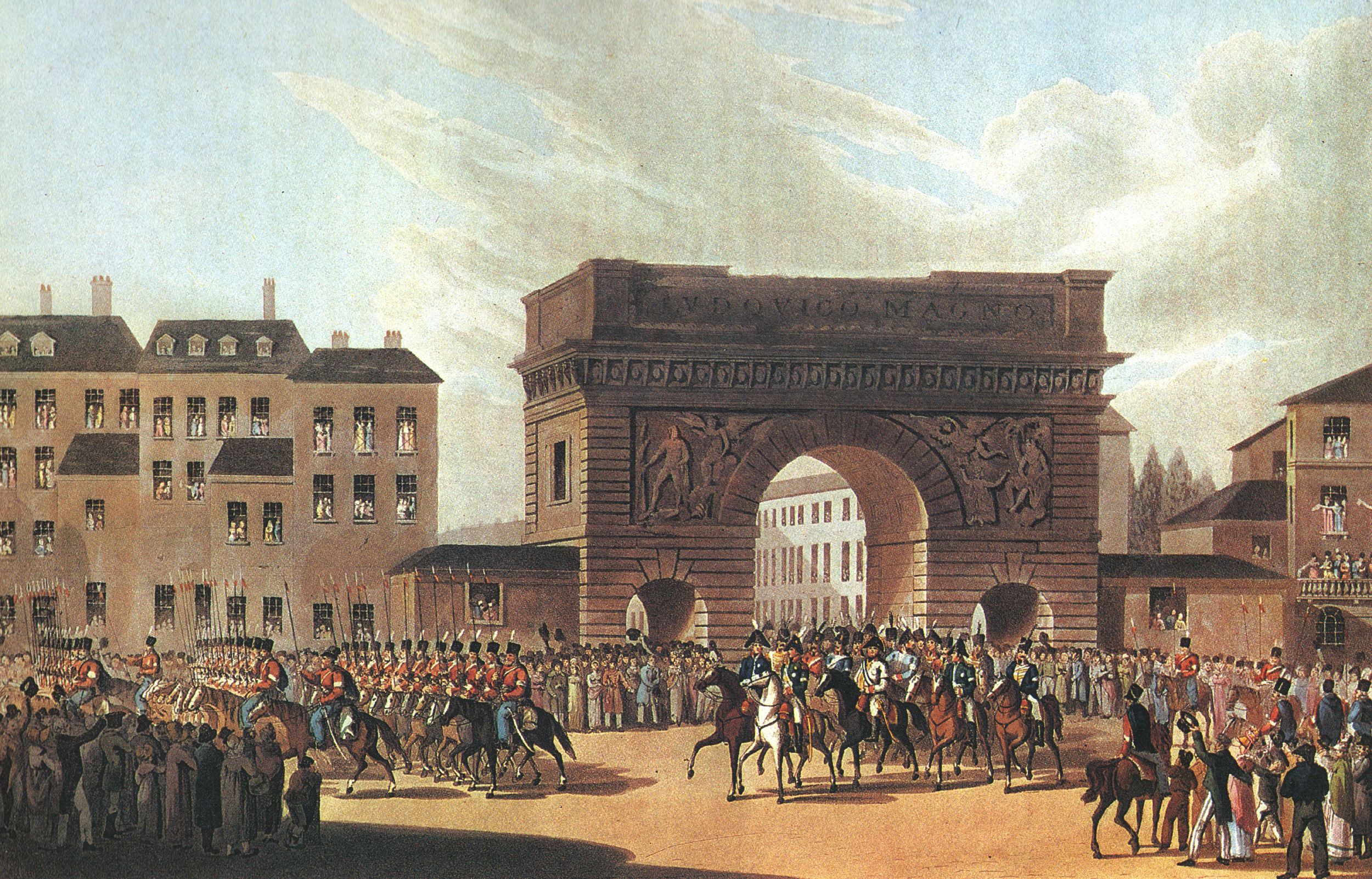

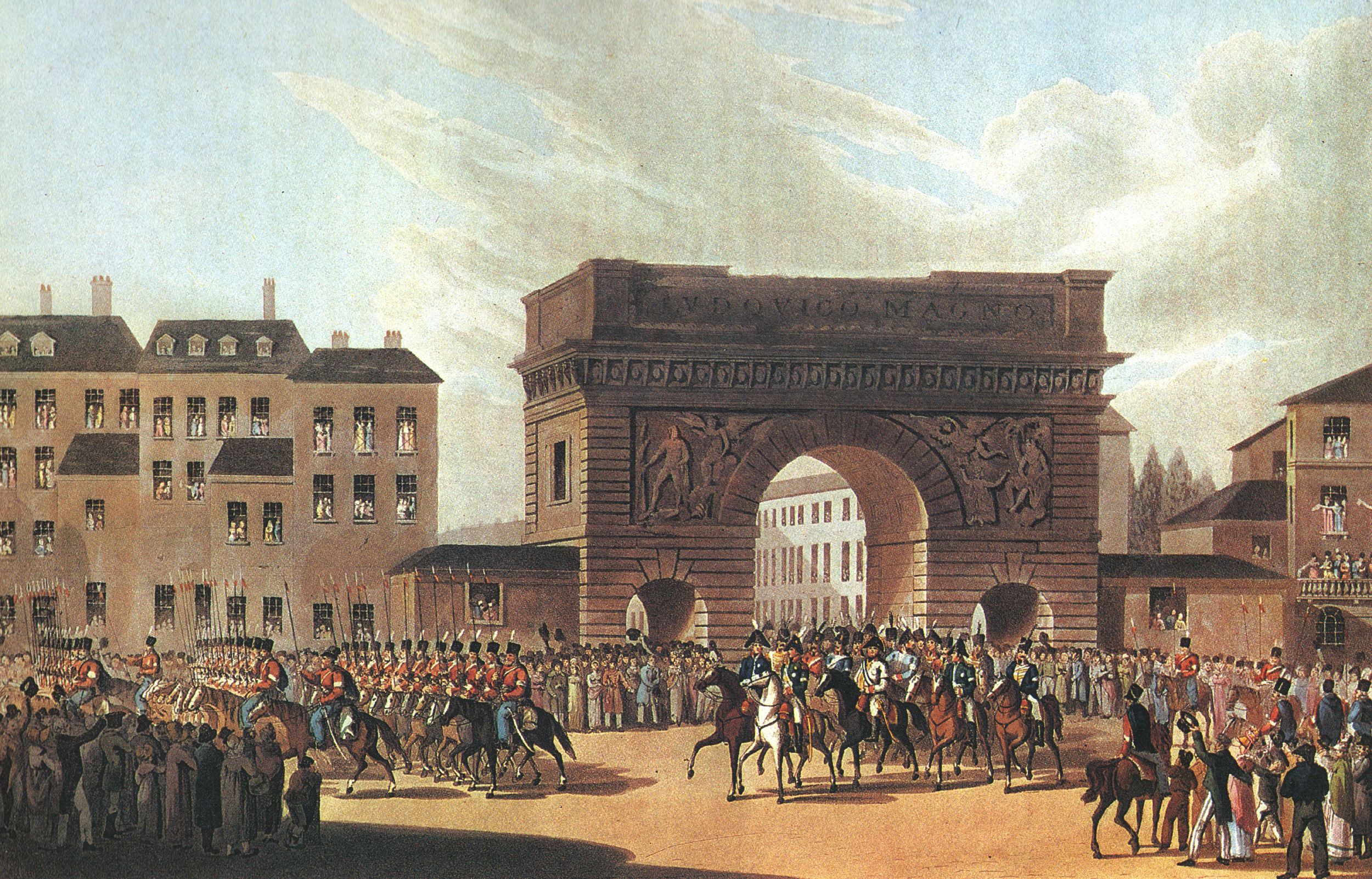

Western Europeans had a lot of contact with Cossacks during the

Western Europeans had a lot of contact with Cossacks during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, and had seen Cossack patrols in Berlin. During Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, Cossacks were the Russian soldiers most feared by the French troops. Napoleon himself stated, "Cossacks are the best light troops among all that exist. If I had them in my army, I would go through all the world with them." Cossacks also took part in the partisan war deep inside French-occupied Russian territory, attacking communications and supply lines. These attacks, carried out by Cossacks along with Russian light cavalry and other units, were one of the first developments of guerrilla warfare tactics and, to some extent, special operations as we know them today.

Don Cossacks

The Don Cossack Host ( ru , Всевеликое Войско Донское, ''Vsevelikoye Voysko Donskoye'') was either an independent or an autonomous democratic republic, located in present-day Southern Russia. It existed from the end of the 16th century until the early 20th century. There are two main theories of the origin of the Don Cossacks. Most respected historians support the migration theory, according to which they were Slavic colonists. The various autochthonous theories popular among the Cossacks themselves do not find confirmation in genetic studies. The gene pool comprises mainly the East Slavic component, with a significant Ukrainian contribution. There is no influence of the peoples of the Caucasus; and the steppe populations, represented by the Nogais, have only limited impact.

The majority of Don Cossacks are either Eastern Orthodox or Christian Old Believers (старообрядцы).

The Don Cossack Host ( ru , Всевеликое Войско Донское, ''Vsevelikoye Voysko Donskoye'') was either an independent or an autonomous democratic republic, located in present-day Southern Russia. It existed from the end of the 16th century until the early 20th century. There are two main theories of the origin of the Don Cossacks. Most respected historians support the migration theory, according to which they were Slavic colonists. The various autochthonous theories popular among the Cossacks themselves do not find confirmation in genetic studies. The gene pool comprises mainly the East Slavic component, with a significant Ukrainian contribution. There is no influence of the peoples of the Caucasus; and the steppe populations, represented by the Nogais, have only limited impact.

The majority of Don Cossacks are either Eastern Orthodox or Christian Old Believers (старообрядцы).[ Prior to the ]Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, there were numerous religious minorities, including Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, Subbotniks, and Jews.

Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks (russian: кубанские казаки, ''kubanskiye kаzaki''; uk, кубанські козаки, ''kubanski kozaky''), or Kubanians (russian: кубанцы, ; uk, кубанці, ), are Cossacks who live in the Kuban r ...

are Cossacks who live in the Kuban region of Russia. Although many Cossack groups came to inhabit the Western North Caucasus, most of the Kuban Cossacks are descendants of the Black Sea Cossack Host

Black Sea Cossack Host (russian: Черномо́рское каза́чье во́йско; uk, Чорномо́рське коза́цьке ві́йсько ), also known as Chernomoriya (russian: Черномо́рия), was a Cossack host ...

(originally the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

), and the Caucasus Line Cossack Host

Caucasus Line Cossack Host (Кавказское линейное казачье войско) was a Cossack host created in 1832 for the purpose of conquest of the Northern Caucasus. Together with the Black Sea Cossack Host it defended the Cauc ...

.

A distinguishing feature is the '' Chupryna'' or ''Oseledets'' hairstyle, a roach

Roach may refer to:

Animals

* Cockroach, various insect species of the order Blattodea

* Common roach (''Rutilus rutilus''), a fresh and brackish water fish of the family Cyprinidae

** ''Rutilus'' or roaches, a genus of fishes

* California roa ...

haircut popular among some Kubanians. This tradition traces back to the Zaporizhian Sich.

Terek Cossacks

The Terek Cossack Host was created in 1577 by free Cossacks resettling from the Volga to the Terek River. Local Terek Cossacks joined this host later. In 1792, the host was included in the Caucasus Line Cossack Host, from which it separated again in 1860, with Vladikavkaz as its capital. In 1916, the population of the host was 255,000, within an area of 1.9 million desyatinas A dessiatin or desyatina (russian: десятина) is an archaic, rudimentary land measurement used in tsarist Russia. A dessiatin is equal to 2,400 square sazhens and is approximately equivalent to 2.702 English acres or 10,926.512 square metres ...

.

Yaik Cossacks

The

The Ural Cossack

The Ural Cossack Host was a cossack host formed from the Ural Cossacks – those Eurasian cossacks settled by the Ural River. Their alternative name, Yaik Cossacks, comes from the old name of the river.

They were also known by the names:

*Rus ...

Host was formed from the Ural Cossacks, who had settled along the Ural River. Their alternative name, Yaik Cossacks, comes from the river's former name, changed by the government after Pugachev's Rebellion of 1773–1775. The Ural Cossacks spoke Russian, and identified as having primarily Russian ancestry, but also incorporated many Tatars

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Turki ...

into their ranks. In 1577, twenty years after Moscow had conquered the Volga from Kazan to Astrakhan,

Razin and Pugachev Rebellions

As a largely independent nation, the Cossacks had to defend their liberties and democratic traditions against the ever-expanding Muscovy, succeeded by Russian Empire. Their tendency to act independently of the Tsardom of Muscovy increased friction. The Tsardom's power began to grow in 1613, with the ascension of Mikhail Romanov to the throne following the Time of Troubles. The government began attempting to integrate the Cossacks into the Muscovite Tsardom by granting elite status and enforcing military service, thus creating divisions among the Cossacks themselves as they fought to retain their own traditions. The government's efforts to alter their traditional nomadic lifestyle resulted in the Cossacks being involved in nearly all the major disturbances in Russia over a 200-year period, including the rebellions led by Stepan Razin and Yemelyan Pugachev.[

] As Muscovy regained stability, discontent grew within the serf and peasant populations. Under Alexis Romanov, Mikhail's son, the

As Muscovy regained stability, discontent grew within the serf and peasant populations. Under Alexis Romanov, Mikhail's son, the Code of 1649

The Sobornoe Ulozhenie ( rus, Соборное уложение, p=sɐˈbornəjə ʊlɐˈʐɛnʲɪjə, t=Council Code) was a legal code promulgated in 1649 by the Zemsky Sobor under Alexis of Russia as a replacement for the Sudebnik of 1550 intr ...

divided the Russian population into distinct and fixed hereditary categories.[ The Code increased tax revenue for the central government, and put an end to nomadism, to stabilize the social order by fixing people on the same land and in the same occupation as their families. Peasants were tied to the land, and townsmen were forced to take on their fathers' occupations. The increased tax burden fell mainly on the peasants, further widening the gap between poor and wealthy. Human and material resources became limited as the government organized more military expeditions, putting even greater strain on the peasants. War with Poland and Sweden in 1662 led to a fiscal crisis, and rioting across the country.][ Taxes, harsh conditions, and the gap between social classes drove peasants and serfs to flee. Many went to the Cossacks, knowing that the Cossacks would accept refugees and free them.

The Cossacks experienced difficulties under Tsar Alexis as more refugees arrived daily. The Tsar gave the Cossacks a subsidy of food, money, and military supplies in return for acting as border defense.][ These subsidies fluctuated often; a source of conflict between the Cossacks and the government. The war with Poland diverted necessary food and military shipments to the Cossacks as fugitive peasants swelled the population of the Cossack host. The influx of refugees troubled the Cossacks, not only because of the increased demand for food, but also because their large number meant the Cossacks could not absorb them into their culture by way of the traditional apprenticeship.][ Instead of taking these steps for proper assimilation into Cossack society, the runaway peasants spontaneously declared themselves Cossacks and lived alongside the true Cossacks, laboring or working as barge-haulers to earn food.

Divisions among the Cossacks began to emerge as conditions worsened and Mikhail's son Alexis took the throne. Older Cossacks began to settle and become prosperous, enjoying privileges earned through obeying and assisting the Muscovite system.][ The old Cossacks started giving up the traditions and liberties that had been worth dying for, to obtain the pleasures of an elite life. The lawless and restless runaway peasants who called themselves Cossacks looked for adventure and revenge against the nobility that had caused them suffering. These Cossacks did not receive the government subsidies that the old Cossacks enjoyed, and had to work harder and longer for food and money.

]

Razin's Rebellion

The divisions between the elite and the lawless led to the formation of a Cossack army, beginning in 1667 under

The divisions between the elite and the lawless led to the formation of a Cossack army, beginning in 1667 under Stenka Razin

Stepan Timofeyevich Razin (russian: Степа́н Тимофе́евич Ра́зин, ; 1630 – ), known as Stenka Razin ( ), was a Cossack leader who led a major uprising against the nobility and tsarist bureaucracy in southern Russia in 16 ...

, and ultimately to the failure of Razin's rebellion.

Stenka Razin was born into an elite Cossack family, and had made many diplomatic visits to Moscow before organizing his rebellion.[ The Cossacks were Razin's main supporters, and followed him during his first Persian campaign in 1667, plundering and pillaging Persian cities on the ]Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

. They returned in 1669, ill and hungry, tired from fighting, but rich with plundered goods.[ Muscovy tried to gain support from the old Cossacks, asking the ataman, or Cossack chieftain, to prevent Razin from following through with his plans. But the ataman was Razin's godfather, and was swayed by Razin's promise of a share of expedition wealth. His reply was that the elite Cossacks were powerless against the band of rebels. The elite did not see much threat from Razin and his followers either, although they realized he could cause them problems with the Muscovite system if his following developed into a rebellion against the central government.][

Razin and his followers began to capture cities at the start of the rebellion, in 1669. They seized the towns of Tsaritsyn, Astrakhan, Saratov, and Samara, implementing democratic rule and releasing peasants from slavery as they went.][ Razin envisioned a united Cossack republic throughout the southern steppe, in which the towns and villages would operate under the democratic, Cossack style of government. Their sieges often took place in the runaway peasant Cossacks' old towns, leading them to wreak havoc there and take revenge on their old masters. The elder Cossacks began to see the rebels' advance as a problem, and in 1671 decided to comply with the government in order to receive more subsidies.][ On April 14, ataman Yakovlev led elders to destroy the rebel camp. They captured Razin, taking him soon afterward to Moscow to be executed.

Razin's rebellion marked the beginning of the end of traditional Cossack practices. In August 1671, Muscovite envoys administered the oath of allegiance and the Cossacks swore loyalty to the tsar.][ While they still had internal autonomy, the Cossacks became Muscovite subjects, a transition that was a dividing point again in Pugachev's Rebellion.

]

Pugachev's Rebellion

For the Cossack elite, noble status within the empire came at the price of their old liberties in the 18th century. Advancing agricultural settlement began to force the Cossacks to give up their traditional nomadic ways and adopt new forms of government. The government steadily changed the entire culture of the Cossacks. Peter the Great increased Cossack service obligations, and mobilized their forces to fight in far-off wars. Peter began establishing non-Cossack troops in fortresses along the Yaik River. In 1734, construction of a government fortress at Orenburg gave Cossacks a subordinate role in border defense.

For the Cossack elite, noble status within the empire came at the price of their old liberties in the 18th century. Advancing agricultural settlement began to force the Cossacks to give up their traditional nomadic ways and adopt new forms of government. The government steadily changed the entire culture of the Cossacks. Peter the Great increased Cossack service obligations, and mobilized their forces to fight in far-off wars. Peter began establishing non-Cossack troops in fortresses along the Yaik River. In 1734, construction of a government fortress at Orenburg gave Cossacks a subordinate role in border defense.[ When the Yaik Cossacks sent a delegation to Peter with their grievances, Peter stripped the Cossacks of their autonomous status, and subordinated them to the War College rather than the College of Foreign Affairs. This consolidated the Cossacks' transition from border patrol to military servicemen. Over the next fifty years, the central government responded to Cossack grievances with arrests, floggings, and exiles.][