Connemara on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the

Connemara lies in the territory of , "West Connacht," within the portion of County Galway west of

Connemara lies in the territory of , "West Connacht," within the portion of County Galway west of

The population of Connemara is 32,000. There are between 20,000–24,000 native Irish speakers in the region, making it the largest Irish-speaking . The Enumeration Districts with the most Irish speakers in all of Ireland, as a percentage of population, can be seen in the South Connemara area. Those of school age (5–19 years old) are the most likely to be identified as speakers.

Connemara, which was formerly called "The Irish Highlands", has had an enormous influence on

The population of Connemara is 32,000. There are between 20,000–24,000 native Irish speakers in the region, making it the largest Irish-speaking . The Enumeration Districts with the most Irish speakers in all of Ireland, as a percentage of population, can be seen in the South Connemara area. Those of school age (5–19 years old) are the most likely to be identified as speakers.

Connemara, which was formerly called "The Irish Highlands", has had an enormous influence on

Connemara after the Famine

at

Love Connemara

– Visitor Guide to the Connemara Region

Connemara News

– Useful source of information for everything related to this area of West Ireland: environment, people, traditions, events, books and movies. {{Authority control Geography of County Galway Gaeltacht places in County Galway O'Flaherty dynasty Conmaicne Mara

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

coast of western County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture

The culture of Ireland includes language, literature, music, art, folklore, cuisine, and sport associated with Ireland and the Irish people. For most of its recorded history, Irish culture has been primarily Gaelic (see Gaelic Ireland). It has ...

and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially reco ...

, which is a key part of the identity of the region and is the largest Gaeltacht in the country. Historically, Connemara was part of the territory of Iar Connacht (West Connacht). Geographically, it has many mountains (notably the Twelve Bens), peninsulas, coves, islands and small lakes. Connemara National Park

Connemara National Park ( ga, Páirc Naisiúnta Chonamara) is one of six national parks in Ireland, managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service. It is located in the northwest of Connemara in County Galway, on the west coast.

History ...

is in the northwest. It is mostly rural and its largest settlement is Clifden.

Etymology

"Connemara" derives from the tribal name , which designated a branch of the , an early tribal grouping that had a number of branches located in different parts of . Since this particular branch of the lived by the sea, they became known as the (sea in Irish is ,genitive

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can a ...

, hence "of the sea").

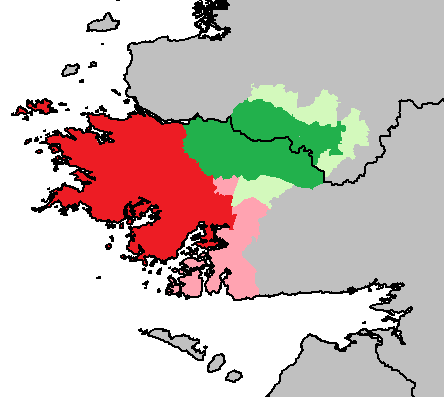

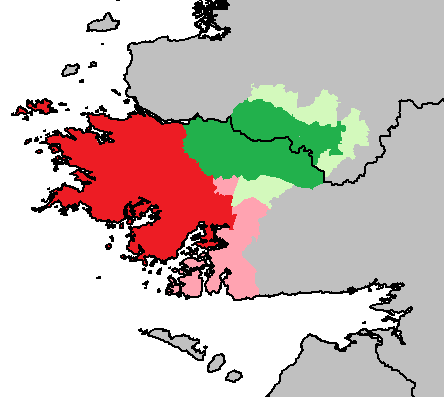

Definition

One common definition of the area is that it consists of most of west Galway, that is to say the part of the county west ofLough Corrib

Lough Corrib ( ; ) is a lake in the west of Ireland. The River Corrib or Galway River connects the lake to the sea at Galway. It is the largest lake within the Republic of Ireland and the second largest on the island of Ireland (after Lough Nea ...

and Galway city, contained by Killary Harbour, Galway Bay

Galway Bay ( Irish: ''Loch Lurgain'' or ''Cuan na Gaillimhe'') is a bay on the west coast of Ireland, between County Galway in the province of Connacht to the north and the Burren in County Clare in the province of Munster to the south; Galw ...

and the Atlantic Ocean. Some more restrictive definitions of Connemara define it as the historical territory of , i.e. just the far northwest of County Galway, bordering County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the yew trees") is a county in Ireland. In the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, now generally known as Mayo Abbey. Mayo County Counci ...

. The name is also used to describe the (Irish-speaking areas) of western County Galway, though it is argued that this too is inaccurate as some of these areas lie outside of the traditional boundary of Connemara. There are arguments about where Connemara ends as it approaches Galway city, which is definitely not in Connemara — some argue for Barna

Barna (Bearna in Irish) is a coastal village on the R336 regional road in Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. It has become a satellite village of Galway city. The village is Irish speaking and is therefore a constituent part of the regions o ...

, on the outskirts of Galway City, some for a line from Oughterard

Oughterard () is a small town on the banks of the Owenriff River close to the western shore of Lough Corrib in Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. The population of the town in 2016 was 1,318. It is located about northwest of Galway on the N59 ...

to Maam Cross, and then diagonally down to the coast, all within rural lands.

The wider area of what is today known as Connemara was previously a sovereign kingdom known as , under the kingship of the , until it became part of the English-administered Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label=Classical Irish, an Ríoghacht Éireann; ga, label= Modern Irish, an Ríocht Éireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from ...

in the 16th century.

Geography

Lough Corrib

Lough Corrib ( ; ) is a lake in the west of Ireland. The River Corrib or Galway River connects the lake to the sea at Galway. It is the largest lake within the Republic of Ireland and the second largest on the island of Ireland (after Lough Nea ...

, and was traditionally divided into North Connemara and South Connemara. The mountains of the Twelve Bens and the Owenglin River, which flows into the sea at / Clifden, marked the boundary between the two parts. Connemara is bounded on the west, south and north by the Atlantic Ocean. In at least some definitions, Connemara's land boundary with the rest of County Galway is marked by the Invermore River otherwise known as (which flows into the north of Kilkieran

Cill Chiaráin (anglicized as Kilkieran) is a coastal village in the Connemara area of County Galway in Ireland. The R340 passes through Cill Chiaráin.

Cill Chiaráin lies in a ''Gaeltacht'' region (Irish-speaking area), and ''Coláiste Sheoi ...

Bay), Loch Oorid

Oorid Lough () is a freshwater lake in the west of Ireland. It is located in the Connemara area of County Galway.

Geography and natural history

Oorid Lough is located along the N59 road about west of Oughterard, and about west of the village ...

(which lies a few kilometres west of Maam Cross) and the western spine of the Maumturks

, photo=View south to Knocknahillion from Letterbreckaun.jpg

, photo_caption= Maumturk Mountains: looking south from Letterbreckaun towards Knocknahillion and Binn idir an dá Log.

, country=Republic of Ireland

, region = Connacht

, region_t ...

mountains. In the north of the mountains, the boundary meets the sea at Killary, a few kilometres west of Leenaun

Leenaun (), also Leenane, is a village and 1,845 acre townland in County Galway, Ireland, on the southern shore of Killary Harbour and the northern edge of Connemara.

Location

Leenaun is situated on the junction of the N59 road, and the R336 r ...

.

The coast of Connemara is made up of multiple peninsulas. The peninsula of (sometimes corrupted to ) in the south is the largest and contains the villages of Carna and Kilkieran

Cill Chiaráin (anglicized as Kilkieran) is a coastal village in the Connemara area of County Galway in Ireland. The R340 passes through Cill Chiaráin.

Cill Chiaráin lies in a ''Gaeltacht'' region (Irish-speaking area), and ''Coláiste Sheoi ...

. The peninsula of Errismore consists of the area west of the village of Ballyconneely

Ballyconneely () is a village and small ribbon development in west Connemara, County Galway Ireland.

Name

19th century antiquarian John O'Donovan documents a number of variants of the village, including Ballyconneely, Baile 'ic Conghaile, Ball ...

. Errisbeg peninsula lies to the south of the village of Roundstone. The Errislannan peninsula lies just south of the town of Clifden. The peninsulas of Kingstown, Coolacloy, Aughrus, Cleggan and Renvyle are found in the north-west of Connemara. Of the numerous islands off the coast of Connemara, Inishbofin is the largest; other islands include Omey, Inishark, High Island, Friars Island, Feenish and Maínis.

The territory contains the civil parishes of Moyrus, Ballynakill, Omey, Ballindoon

Ballindoon () Friary was a Dominican priory beside Lough Arrow in County Sligo

County Sligo ( , gle, Contae Shligigh) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the Border Region and is part of the province of Connacht. Sligo is the administr ...

and Inishbofin (the last parish was for a time part of the territory of the , the O Malleys of the territory of Umhall, County Mayo), and the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

parishes of Carna, Clifden (Omey and Ballindoon

Ballindoon () Friary was a Dominican priory beside Lough Arrow in County Sligo

County Sligo ( , gle, Contae Shligigh) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the Border Region and is part of the province of Connacht. Sligo is the administr ...

), Ballynakill

Ballinakill () is a small village in County Laois, Ireland on the R432 regional road between Abbeyleix, Ballyragget and Castlecomer, County Kilkenny. As of the 2016 census, there were 445 people living in Ballinakill.

History

From 1613 until ...

, Kilcumin (Oughterard and Rosscahill), Roundstone and Inishbofin.

History

The main town of Connemara is Clifden, which is surrounded by an area rich withmegalithic

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

tombs.

The famous " Connemara Green marble" is found outcropping along a line between Streamstown

Streamstown () is a village in County Westmeath, Ireland. It sits roughly 20 km from the county town of Mullingar. Streamstown was historically called ''Ballintruhan'', which is an anglicisation of its Irish name.

A horse named '' Streamstown'' ...

and Lissoughter

Lissoughter () at , does not qualify to be an Arderin or a Vandeleur-Lynam, however, its prominence of ranks it as a Marilyn.Mountainviews, (September 2013), "A Guide to Ireland's Mountain Summits: The Vandeleur-Lynams & the Arderins", Colli ...

. It was a trade treasure used by the inhabitants in prehistoric times. It continues to be of great value today. It is available in large dimensional slabs suitable for buildings as well as for smaller pieces of jewellery. It is used for the pendant for the Chief Scout's Award, the highest award in Scouting Ireland

Scouting Ireland ( ga, Gasóga na hÉireann) is one of the largest youth movements on the island of Ireland, a voluntary educational movement for young people with over 45,000 members, including over 11,000 adult volunteers . Of the 750,000 peo ...

.

The east of what is now Connemara was once called , and was ruled by Kings who claimed descent from the Delbhna

The Delbna or Delbhna were a Gaelic Irish tribe in Ireland, claiming kinship with the Dál gCais, through descent from Dealbhna son of Cas. Originally one large population, they had a number of branches in Connacht, Meath, and Munster in Irela ...

and Dál gCais

The Dalcassians ( ga, Dál gCais ) are a Gaelic Irish clan, generally accepted by contemporary scholarship as being a branch of the Déisi Muman, that became very powerful in Ireland during the 10th century. Their genealogies claimed descent f ...

of Thomond and kinship with King Brian Boru

Brian Boru ( mga, Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig; modern ga, Brian Bóramha; 23 April 1014) was an Irish king who ended the domination of the High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill and probably ended Viking invasion/domination of Ireland. ...

. The Kings of Delbhna Tír Dhá Locha eventually took the title and surname Mac Con Raoi (since anglicised as Conroy or King).

The Chief of the Name

The Chief of the Name, or in older English usage Captain of his Nation, is the recognised head of a family or clan (''fine'' in Irish and Scottish Gaelic). The term has sometimes been used as a title in Ireland and Scotland.

In Ireland

In Eliz ...

of Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, mea ...

Mac Con Raoi directly ruled as Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage ...

of Gnó Mhór, which was later divided into the civil parishes of Kilcummin and Killannin. Due to the power they wielded through their war galleys, the Chiefs of Clan Mac Con Raoi were traditionally considered to be, along with the Chiefs of Clans O'Malley, O'Dowd, and O'Flaherty, the Sea Kings of Connacht. The nearby kingdom of Gnó Beag was ruled by the Chief of the Name

The Chief of the Name, or in older English usage Captain of his Nation, is the recognised head of a family or clan (''fine'' in Irish and Scottish Gaelic). The term has sometimes been used as a title in Ireland and Scotland.

In Ireland

In Eliz ...

of Clan Ó hÉanaí (usually anglicised as Heaney or Heeney).

The (Kealy) clan were the rulers of West Connemara. Like the Chiefs of Clan clan, the Chiefs of Clan (Conneely) also claimed descent from the .

During the early 13th-century

The 13th century was the century which lasted from January 1, 1201 ( MCCI) through December 31, 1300 ( MCCC) in accordance with the Julian calendar.

The Mongol Empire was founded by Genghis Khan, which stretched from Eastern Asia to Eastern Eur ...

, however, all four clans were displaced and subjugated by the Chiefs of Clan , who had been driven west from into by the Mac William Uachtar

Clanricarde (; ), also known as Mac William Uachtar (Upper Mac William) or the Galway Burkes, were a fully Gaelicised branch of the Hiberno-Norman House of Burgh who were important landowners in Ireland from the 13th to the 20th centuries.

...

branch of the House of Burgh, during the Hiberno-Norman

From the 12th century onwards, a group of Normans invaded and settled in Gaelic Ireland. These settlers later became known as Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans. They originated mainly among Cambro-Norman families in Wales and Anglo-Normans fro ...

invasion of .

According to Irish-American historian Bridget Connelly, "By the thirteenth century, the original inhabitants, the clans Conneely, Ó Cadhain, Ó Folan, and MacConroy, had been steadily driven westward from the Moycullen area to the seacoast between Moyrus and the Killaries. And by 1586, with the signing of the Articles of the Composition of Connacht that made Morrough O'Flaherty landlord over all in the name of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, the MacConneelys and Ó Folans had sunk beneath the list of chieftains whose names appeared on the document. The Articles deprived all the original Irish clan chieftains not only of their title but also all of the rents, dues, and tribal rights they had possessed under Irish law Law of Ireland or Irish law may refer to:

* Early Irish law (Brehon law) of Medieval Ireland

* Alternative law in Ireland prior to 1921

* Law of the Republic of Ireland

The law of Ireland consists of constitutional, statute, and common law. ...

."

During the 16th-century, however, legendary local pirate queen Grace O'Malley

Grace O'Malley ( – c. 1603), also known as Gráinne O'Malley ( ga, Gráinne Ní Mháille, ), was the head of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland, and the daughter of Eóghan Dubhdara Ó Máille.

In Irish folklore she is commonly ...

is on record as having said, with regard to her followers, "''Go mb'fhearr léi lán loinge de chlann Chonraoi agus de chlann Mhic an Fhailí ná lán loinge d'ór''" (that she would rather have a shipload of Conroys and MacAnallys than a shipload of gold).Ordnance Survey Letters, Mayo, vol. II, cited in Anne Chambers (2003), ''The Pirate Queen'', but with spelling modernised.

One of the last Chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the bo ...

s of Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, mea ...

O'Flaherty and Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage ...

of Iar Connacht was the 17th-century

The 17th century lasted from January 1, 1601 ( MDCI), to December 31, 1700 ( MDCC). It falls into the early modern period of Europe and in that continent (whose impact on the world was increasing) was characterized by the Baroque cultural movemen ...

historian Ruaidhrí Ó Flaithbheartaigh

Roderick O'Flaherty ( ga, Ruaidhrí Ó Flaithbheartaigh; 1629–1718 or 1716) was an Irish historian.

Biography

He was born in County Galway and inherited Moycullen Castle and estate.

O'Flaherty was the last ''de jure'' Lord of Iar Connacht, ...

, who lost the greater part of his ancestral lands during the Cromwellian confiscations of the 1650s.

After being dispossessed, Ó Flaithbheartaigh settled near Spiddal

Spiddal ( ga, An Spidéal , meaning 'the hospital') is a village on the shore of Galway Bay in County Galway, Ireland. It is west of Galway city, on the R336 road. It is on the eastern side of the county's Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking area) an ...

wrote a book of Irish history

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 33,000 years ago, with further findings dating the presence of homo sapiens to around 10,500 to 7,000 BC. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Quaterna ...

in New Latin

New Latin (also called Neo-Latin or Modern Latin) is the revival of Literary Latin used in original, scholarly, and scientific works since about 1500. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy ...

titled ''Ogygia'', which was published in 1685 as ''Ogygia: seu Rerum Hibernicarum Chronologia & etc.'', in 1793 it was translated into English by Rev. James Hely, as ''Ogygia, or a Chronological account of Irish Events (collected from Very Ancient Documents faithfully compared with each other & supported by the Genealogical & Chronological Aid of the Sacred and Profane Writings of the Globe''. Ogygia, the island of Calypso in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''The Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'', was used by Ó Flaithbheartaigh as a poetic allegory for Ireland. Drawing from numerous ancient documents, ''Ogygia'' traces Irish history

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 33,000 years ago, with further findings dating the presence of homo sapiens to around 10,500 to 7,000 BC. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Quaterna ...

back before Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, Pádraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints b ...

and into Pre-Christian Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths native to the island of Ireland. It was originally oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era, being part of ancient Celtic religion. Many myths were later Early Irish ...

.

Even so, another branch, also descended from the derbhfine of the Chiefs, continued to live in a thatch-covered long house at Renvyle and to act as both clan leaders and agents for the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

Blake family. This arrangement continued until 1811, when Henry Blake ended a 130-year-long tradition of his family acting as absentee landlord

In economics, an absentee landlord is a person who owns and rents out a profit-earning property, but does not live within the property's local economic region. The term "absentee ownership" was popularised by economist Thorstein Veblen's 1923 book ...

s and evicted 86-year-old Anthony O'Flaherty, his relatives, and his retainers. Henry Blake then demolished Anthony O'Flaherty's longhouse and built Renvyle House on the site.

Even though Henry Blake later termed the eviction of Anthony O'Flaherty in ''Letters from the Irish Highlands'', as "the dawn of law in Cunnemara" ( sic), the Blake family is not remembered warmly in the region. Contemporary Anglo-Irish landlord John D'Arcy, who bankrupted both himself and his heirs to found the town of Clifden, is recalled much more fondly.

Connemara was drastically depopulated during the Great Famine in the late 1840s, with the lands of the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

Martin family being greatly affected and the bankrupted landlord being forced to auction off the estate in 1849:

The Sean nós song '' Johnny Seoighe'' is one of the few Irish songs from the era of the Great Famine that still survives.

The Irish Famine of 1879 similarly caused mass starvation, evictions, and violence in Connemara against the abuses of power by local Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

landlords, bailiffs, and the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

. In response, Father Patrick Grealy, the Roman Catholic priest assigned to Carna, selected ten, "very destitute but industrious and virtuous families", from his parish to emigrate to America and be settled upon frontier homesteads in Moonshine Township, near Graceville, Minnesota

Graceville is a city in Big Stone County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 529 at the 2020 census.

History

Graceville was founded in the 1870s by a colony of Catholics and named for Thomas Langdon Grace, second Roman Catholic Bisho ...

, by Bishop John Ireland

John Benjamin Ireland (January 30, 1914 – March 21, 1992) was a Canadian actor. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in ''All the King's Men'' (1949), making him the first Vancouver-born actor to receive an Oscar nomin ...

of the Roman Catholic Diocese of St. Paul.

According to historian Cormac Ó Comhraí, during the decades immediately preceding the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, politics in Connemara was largely dominated by the pro-Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wi ...

Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nation ...

and its ally, the United Irish League. At the same time, though, despite an almost complete absence of the Sinn Fein political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

in Connemara, the militantly anti-monarchist Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

had a number of active units throughout the region. Furthermore, many County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

veterans of the subsequent Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

traced their belief in Irish republicanism

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

to a father or grandfather who had been in the IRB.

The first transatlantic flight, piloted by British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown, landed in a boggy area near Clifden in 1919.

Renvyle House was burned down by the Anti-Treaty IRA

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

during the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

, but later rebuilt by Oliver St John Gogarty and turned into a hotel.

Irish language, literature, and folklore

The population of Connemara is 32,000. There are between 20,000–24,000 native Irish speakers in the region, making it the largest Irish-speaking . The Enumeration Districts with the most Irish speakers in all of Ireland, as a percentage of population, can be seen in the South Connemara area. Those of school age (5–19 years old) are the most likely to be identified as speakers.

Connemara, which was formerly called "The Irish Highlands", has had an enormous influence on

The population of Connemara is 32,000. There are between 20,000–24,000 native Irish speakers in the region, making it the largest Irish-speaking . The Enumeration Districts with the most Irish speakers in all of Ireland, as a percentage of population, can be seen in the South Connemara area. Those of school age (5–19 years old) are the most likely to be identified as speakers.

Connemara, which was formerly called "The Irish Highlands", has had an enormous influence on Irish culture

The culture of Ireland includes language, literature, music, art, folklore, cuisine, and sport associated with Ireland and the Irish people. For most of its recorded history, Irish culture has been primarily Gaelic (see Gaelic Ireland). It has ...

, literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

, and folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

.

Micheál Mac Suibhne

Mícheál or Micheál Mac Suibhne () was an Irish language bard from the Connemara Gaeltacht.

Life

Mac Suibhne was born near the ruined Abbey of Cong, then part of County Galway, but now in County Mayo. The names of his parents are not recorded, ...

(), a Connacht Irish bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise ...

mainly associated with Cleggan

Cleggan () is a fishing village in County Galway, Ireland. The village lies 10 km (7 mi) northwest of Clifden and is situated at the head of Cleggan Bay.

A focal point of the village is the pier, built by Alexander Nimmo in 1822 an ...

, remains a locally revered figure, due to his genius level contribution to oral poetry

Oral poetry is a form of poetry that is composed and transmitted without the aid of writing. The complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain.

Background

Oral poetry is ...

and sean-nós singing

Sean-nós singing ( , ; Irish for "old style") is unaccompanied traditional Irish vocal music usually performed in the Irish language. Sean-nós singing usually involves very long melodic phrases with highly ornamented and melismatic melodic ...

in Connacht Irish.

After emigrating from Connemara to the United States during the 1860s, Bríd Ní Mháille, a Bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise ...

in the Irish language outside Ireland

The Irish language originated in Ireland and has historically been the dominant language of the Irish people. They took it with them to a number of other countries, and in Scotland and the Isle of Man it gave rise to Scottish Gaelic and Manx, res ...

and sean-nós singer from the village of Trá Bhán, Garmna

Gorumna () is an island on the west coast of Ireland, forming part of County Galway.

Geography

Gorumna Island is linked with the mainland through the Béal an Daingin Bridge.

Gorumna properly consists of three individual islands in close p ...

, composed the '' caoine'' '' Amhrán na Trá Báine''. The song is about the drowning of her three brothers after '' currach'' was rammed and sunk while they were out at sea. Ní Mháille's lament for her brothers was first performed at a ceilidh in South Boston, Massachusetts

South Boston is a densely populated neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, located south and east of the Fort Point Channel and abutting Dorchester Bay. South Boston, colloquially known as Southie, has undergone several demographic transforma ...

before being brought back to Connemara, where it is considered an ''Amhrán Mór'' ("Big Song") and remains a very popular song among both performers and fans of both sean-nós singing

Sean-nós singing ( , ; Irish for "old style") is unaccompanied traditional Irish vocal music usually performed in the Irish language. Sean-nós singing usually involves very long melodic phrases with highly ornamented and melismatic melodic ...

and Irish traditional music.

During the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

, Irish teacher and nationalist Patrick Pearse, who would go on to lead the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

before being executed by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are us ...

, owned a cottage at Rosmuc

Rosmuc or Ros Muc, sometimes anglicised as Rosmuck, is a village in the Conamara Gaeltacht of County Galway, Ireland. It lies halfway between the town of Clifden and the city of Galway. Irish is the predominant spoken language in the area, with ...

, where he spent his summers learning the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

and writing. According to ''Innti

''Innti'' was a literary movement of poets writing Modern literature in Irish, associated with a journal of the same name founded in 1970 by Michael Davitt, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Gabriel Rosenstock, Louis de Paor and Liam Ó Muirthile. These ...

'' poet and literary critic

Literary criticism (or literary studies) is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical discussion of literature's goals and methods. ...

Louis de Paor, despite Pearse's enthusiasm for the '' Conamara Theas'' dialect of Connacht Irish spoken around his summer cottage, he chose to follow the usual practice of the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

by writing in Munster Irish, which was considered less Anglicized

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influenc ...

than other Irish dialects. At the same time, however, Pearse's reading of the radically experimental poetry of Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

and of the French Symbolists

Symbolism was a late 19th-century art movement of French and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts seeking to represent absolute truths symbolically through language and metaphorical images, mainly as a reaction against naturalism and real ...

led him to introduce Modernist poetry

Modernist poetry refers to poetry written between 1890 and 1950 in the tradition of modernist literature, but the dates of the term depend upon a number of factors, including the nation of origin, the particular school in question, and the biases ...

into the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

. As a literary critic

Literary criticism (or literary studies) is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical discussion of literature's goals and methods. ...

, Pearse also left behind a very detailed blueprint for the decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

of Irish literature, particularly in the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

.

During the aftermath of the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

and the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, Connemara was a major center for the work of the Irish Folklore Commission in recording Ireland's endangered folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

, mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narra ...

, and oral literature

Oral literature, orature or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung as opposed to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used var ...

. According to folklore collector and archivist Seán Ó Súilleabháin, residents with no stories to tell were the exception rather than the rule and it was generally conceded in 1935 that there were more unrecorded folktales in the parish of Carna alone than anywhere else in Western Europe.

One of the most important tradition bearers the Commission recorded in Connemara or anywhere else was Éamon a Búrc. Before his repertoire of tales was recorded and transcribed, a Búrc had emigrated to America and lived in Graceville, Minnesota

Graceville is a city in Big Stone County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 529 at the 2020 census.

History

Graceville was founded in the 1870s by a colony of Catholics and named for Thomas Langdon Grace, second Roman Catholic Bisho ...

and in the Connemara Patch

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the Atlantic coast of western County Galway, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht, w ...

shantytown in the Twin Cities

Twin cities are a special case of two neighboring cities or urban centres that grow into a single conurbation – or narrowly separated urban areas – over time. There are no formal criteria, but twin cities are generally comparable in sta ...

. After returning to his native Carna, Éamon a Búrc became a tailor and was recorded in 1935 at the home now owned the Ó Cuaig family. Furthermore, according to Irish-American historian Bridget Connelly, the stories collected in Irish from Éamon a Búrc are still taught in University courses alongside ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. ...

'', the Elder Edda and the Homeric Hymns

The ''Homeric Hymns'' () are a collection of thirty-three anonymous ancient Greek hymns celebrating individual gods. The hymns are "Homeric" in the sense that they employ the same epic meter— dactylic hexameter—as the ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey'' ...

.

Joe Heaney

Joe Heaney (AKA Joe Éinniú; Irish: Seosamh Ó hÉanaí) (1 October 1919 – 1 May 1984) was an Irish traditional ( sean nós) singer from County Galway, Ireland. He spent most of his adult life abroad, living in England, Scotland and New York ...

a legendary seanchai and sean-nós singer in Connacht Irish, is said to have known more than 500 songs – most learned from his family while he was growing up in Carna. The Féile Chomórtha Joe Éinniú (Joe Heaney Commemorative Festival) is held every year in Carna.

Sorcha Ní Ghuairim

Sorcha Ní Ghuairim (11 October 1911 – 1976) was a teacher, writer, and sean-nós singer.

Life

Sorcha Ní Ghuairim was born in Roisín na Manach, Carna in the Connemara Gaeltacht in County Galway on 11 October 1911. Her parents were Mái ...

, a Sean-nós singer and writer of Modern literature in Irish

Although Irish has been used as a literary language for more than 1,500 years (see Irish literature), and modern literature in Irish dates – as in most European languages – to the 16th century, modern Irish literature owes much of its popular ...

, was also born in Connemara. Initially a newspaper columnist termed ‘Coisín Siúlach’ for the newspaper ''The Irish Press'', where she eventually became the editor. She also wrote a regular column for the children's page under the pen name ‘Niamh Chinn Óir’. Her other writings included a series of children's stories titled ''Eachtraí mhuintir Choinín'' and ''Sgéal Taimín Mhic Luiche''. With the assistance of Pádraig Ó Concheanainn, Sorcha also translated Charles McGuinness

Charles John 'Nomad' McGuinness (6 March 1893 – 7 December 1947) was an Irish adventurer supposed to have been involved with a myriad of acts of patriotism and nomadic impulses. Due to a habitual trait of embellishing his own life story mixed ...

' ''Viva Irlanda'' for publication in the newspaper. Their translation was subsequently published under the title ''Ceathrar comrádaí'' in 1943.

While living at Inverin, Connemara during the Emergency

An emergency is an urgent, unexpected, and usually dangerous situation that poses an immediate risk to health, life, property, or environment and requires immediate action. Most emergencies require urgent intervention to prevent a worsening ...

, however, Calum Maclean, the brother of highly important Scottish Gaelic poet Sorley MacLean, was appointed by Professor Séamus Ó Duilearga

Séamus Ó Duilearga (born James Hamilton Delargy; 26 May 1899 – 25 June 1980) was an Irish folklorist, professor of folklore at University College Dublin and Director of the Irish Folklore Commission.

Born in Cushendall, Co Antrim, he was one ...

(1899–1980) as a part-time collector for the Irish Folklore Commission (''Coimisiún Béaloideasa Éireann''). From August 1942 to February 1945, Maclean sent a considerable amount of lore in the local Conamara Theas dialect of Connaught Irish

Connacht Irish () is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Connacht. Gaeltacht regions in Connacht are found in Counties Mayo (notably Tourmakeady, Achill Island and Erris) and Galway (notably in parts of Connemara and on ...

to the Commission, amounting to six bound volumes. From March 1945 Maclean was employed as a temporary cataloguer by the Commission in Dublin, before being sent to the Scottish Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The term ...

to collect folklore there as well, first for the Irish Folklore Commission and later for the School of Scottish Studies

The School of Scottish Studies ( gd, Sgoil Eòlais na h-Alba, sco, Scuil o Scots Studies) was founded in 1951 at the University of Edinburgh. It holds an archive of approximately 33,000 field recordings of traditional music, song and other lo ...

.

While interned during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

in the Curragh Camp

The Curragh Camp ( ga, Campa an Churraigh) is an army base and military college in The Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. It is the main training centre for the Irish Defence Forces and is home to 2,000 military personnel.

History

Longstanding ...

by Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legislature) and the of ...

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

, Máirtín Ó Cadhain

Máirtín Ó Cadhain (; 1906 – 18 October 1970) was one of the most prominent Irish language writers of the twentieth century. Perhaps best known for his 1949 novel '' Cré na Cille'', Ó Cadhain played a key role in reintroducing literary mo ...

, a Post-Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

from An Spidéal

Spiddal ( ga, An Spidéal , meaning 'the hospital') is a village on the shore of Galway Bay in County Galway, Ireland. It is west of Galway city, on the R336 road. It is on the eastern side of the county's Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking area) an ...

, became one of the most radically innovative writers of Modern literature in Irish

Although Irish has been used as a literary language for more than 1,500 years (see Irish literature), and modern literature in Irish dates – as in most European languages – to the 16th century, modern Irish literature owes much of its popular ...

by writing the comic

a medium used to express ideas with images, often combined with text or other visual information. It typically the form of a sequence of panels of images. Textual devices such as speech balloons, captions, and onomatopoeia can indicate ...

and modernist

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

literary classic

A classic is a book accepted as being exemplary or particularly noteworthy. What makes a book "classic" is a concern that has occurred to various authors ranging from Italo Calvino to Mark Twain and the related questions of "Why Read the Cla ...

''Cré na Cille

() is an Irish language novel by Máirtín Ó Cadhain. It was first published in 1949. It is considered one of the greatest novels written in the Irish language.

Title

''Cré na Cille'' literally means "Earth of the Church"; it has also been t ...

''.

The novel is written almost entirely as conversation between the dead bodies buried underneath a Connemara cemetery. In a departure from Patrick Pearse's idealization of the un-Anglicised Irish culture

The culture of Ireland includes language, literature, music, art, folklore, cuisine, and sport associated with Ireland and the Irish people. For most of its recorded history, Irish culture has been primarily Gaelic (see Gaelic Ireland). It has ...

of the Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially reco ...

aí, the deceased speakers in ''Cré na Cille'' spend the whole novel gossiping, backbiting, flirting, feuding, and scandal-mongering. ''Cré na Cille'' is widely considered a masterpiece of 20th-century

The 20th (twentieth) century began on

January 1, 1901 ( MCMI), and ended on December 31, 2000 ( MM). The 20th century was dominated by significant events that defined the modern era: Spanish flu pandemic, World War I and World War II, nucle ...

Irish literature and has drawn comparisons to the writings of Flann O’Brien, Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish novelist, dramatist, short story writer, theatre director, poet, and literary translator. His literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal and Tragicomedy, tr ...

and James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the Modernism, modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important ...

.

Through ''Cré na Cille'' and his other writings, Máirtín Ó Cadhain became a major part of the revival of literary modernism

Literary modernism, or modernist literature, originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterized by a self-conscious break with traditional ways of writing, in both poetry and prose fiction writing. Modernism experimented ...

in Irish, where it had been largely dormant since the execution of Patrick Pearse in 1916. Ó Cadhain created a literary language

A literary language is the form (register) of a language used in written literature, which can be either a nonstandard dialect or a standardized variety of the language. Literary language sometimes is noticeably different from the spoken langua ...

for his writing out of the Conamara Theas and Cois Fharraige

(, lit. "Beside the Sea"/ "Seaside"), previously spelled , is a coastal area west of Galway city, where the Irish language is the predominant language (a ). It stretches from , , to . There are between 8,000 and 9,000 people living in this ar ...

dialects of Connacht Irish, but he was often accused of an unnecessarily dialectal usage in grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes doma ...

and orthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Most transnational languages in the modern period have a writing system, and ...

even in contexts where realistic depiction of the Connemara vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

wasn't called for. He was also happy to experiment with borrowings from other dialects, Classical Irish

Classical Gaelic or Classical Irish () was a shared literary form of Gaelic that was in use by poets in Scotland and Ireland from the 13th century to the 18th century.

Although the first written signs of Scottish Gaelic having diverged from Iri ...

and even Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

. Consequently, much of what Ó Cadhain wrote is, like the poetry of fellow Linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

experimentalist Liam S. Gógan, reputedly very hard to understand for a non-native speaker.

In addition to his writings, Máirtín Ó Cadhain was also instrumental in preaching what he called ''Athghabháil na hÉireann'' ("Re-Conquest of Ireland"), (meaning both decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

and re-Gaelicisation

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaelic, or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread from Ire ...

) and in the 1969 founding of Coiste Cearta Síbialta na Gaeilge

Gluaiseacht Cearta Sibhialta na Gaeltachta ( English: "The Gaeltacht Civil Rights Movement") or Coiste Cearta Síbialta na Gaeilge ( English: Irish Language Civil Rights Committee"), was a pressure group campaigning for social, economic and cul ...

(English: Irish Language Civil Rights Committee"), a pressure group campaigning for social, economic and cultural rights

Economic, social and cultural rights, (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Econo ...

for native-speakers of the Irish-language in Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially reco ...

areas and which drew inspiration from the use of civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". H ...

by the contemporary Welsh Language Society

The Welsh Language Society ( cy, Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg, often abbreviated to Cymdeithas yr Iaith or just Cymdeithas) is a direct action pressure group in Wales campaigning for the right of Welsh people to use the Welsh language in every as ...

, the Northern Ireland civil rights movement

The Northern Ireland civil rights movement dates to the early 1960s, when a number of initiatives emerged in Northern Ireland which challenged the inequality and discrimination against ethnic Irish Catholics that was perpetrated by the Ulster ...

, and the American civil rights movement.

One of their most successful protests involved the pirate radio

Pirate radio or a pirate radio station is a radio station that broadcasts without a valid license.

In some cases, radio stations are considered legal where the signal is transmitted, but illegal where the signals are received—especially ...

station Saor Raidió Chonamara (Free Radio Connemara) which first came on the air during Oireachtas na Gaeilge 1968, as a direct challenge to the Irish government

The Government of Ireland ( ga, Rialtas na hÉireann) is the cabinet that exercises executive authority in Ireland.

The Constitution of Ireland vests executive authority in a government which is headed by the , the head of government. The gover ...

's inaction regarding Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

broadcasting. The station used a medium wave

Medium wave (MW) is the part of the medium frequency (MF) radio band used mainly for AM radio broadcasting. The spectrum provides about 120 channels with more limited sound quality than FM stations on the FM broadcast band. During the dayti ...

transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna. The transmitter itself generates a radio frequency alternating current, which is applied to the ...

smuggled in from the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. The Irish government responded by proposing a national Irish-language radio station RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta which came on the air on Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel P ...

1972. Its headquarters are now in Casla

Casla (Costello or Costelloe) is a Gaeltacht village between Indreabhán (Inverin) and An Cheathrú Rua (Carraroe) in western County Galway, Ireland. The headquarters of RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta is located there. The village lies on the R3 ...

.

In 1974, Gluaiseacht also persuaded Conradh na Gaeilge

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it eme ...

to end the practice since 1939 of always holding Oireachtas na Gaeilge, a cultural and literary festival modeled after the Welsh Eisteddfod

In Welsh culture, an ''eisteddfod'' is an institution and festival with several ranked competitions, including in poetry and music.

The term ''eisteddfod'', which is formed from the Welsh morphemes: , meaning 'sit', and , meaning 'be', means, ac ...

, in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

rather than in the Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially reco ...

areas. Gluaisceart also successfully secured recognition of sean-nós dance in 1977.

Recently, the Coláiste Lurgan, a language immersion

Language immersion, or simply immersion, is a technique used in bilingual language education in which two languages are used for instruction in a variety of topics, including math, science, or social studies. The languages used for instruction ...

summer college located at Inverin, has won worldwide acclaim for their Irish language covers of pop songs,including Leonard Cohen

Leonard Norman Cohen (September 21, 1934November 7, 2016) was a Canadian singer-songwriter, poet and novelist. His work explored religion, politics, isolation, depression, sexuality, loss, death, and romantic relationships. He was inducted in ...

's ''Hallelujah

''Hallelujah'' ( ; he, ''haləlū-Yāh'', meaning "praise Yah") is an interjection used as an expression of gratitude to God. The term is used 24 times in the Hebrew Bible (in the book of Psalms), twice in deuterocanonical books, and four tim ...

'', Adele

Adele Laurie Blue Adkins (, ; born 5 May 1988), professionally known by the mononym Adele, is an English singer and songwriter. After graduating in arts from the BRIT School in 2006, Adele signed a rec ...

's '' Hello'', and Avicii

Tim Bergling (; 8 September 1989 – 20 April 2018), known professionally as Avicii (, ), was a Swedish DJ, remixer and music producer. At the age of 16, Bergling began posting his remixes on electronic music forums, which led to his first re ...

's '' Wake Me Up'', on the TG Lurgan

TG Lurgan is a musical project launched by Coláiste Lurgan, an independent summer school based in Connemara, a Gaeltacht, where the Irish language is the predominant spoken language. TG Lurgan releases interpretations as covers of many popular ...

YouTube channel. The band Seo Linn

Seo Linn (; "here we go") is an Irish folk/indie group formed in Ireland that has been making music and performing since 2013. The group consists of Stiofán Ó Fearail on vocals and guitar, Daithí Ó Ruaidh on vocals, keyboard, and saxophone, K ...

is composed of musicians who met at the college.

Transport

Connemara is accessible by the and City Link bus services. From 1895 to 1935 it was served by the Midland Great Western Railway branch that connected Galway City to Clifden. The N59 is the main area road, following an inland route from Galway to Clifden. A popular alternative is the coastal route beginning with the R336 from Galway. This is also known as the Connemara Loop consisting of a 45 km drive where one can view the landscape and scenery of Connemara. Aer Arann Islands serves theAran Islands

The Aran Islands ( ; gle, Oileáin Árann, ) or The Arans (''na hÁrainneacha'' ) are a group of three islands at the mouth of Galway Bay, off the west coast of Ireland, with a total area around . They constitute the historic barony of Aran i ...

from Connemara Airport in the south of Connemara also known as .

Notable places

Towns and villages

These settlements are within the most extensive definition of the area. More restrictive definitions will exclude some: *Barna

Barna (Bearna in Irish) is a coastal village on the R336 regional road in Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. It has become a satellite village of Galway city. The village is Irish speaking and is therefore a constituent part of the regions o ...

– ()

* Ballyconneely

Ballyconneely () is a village and small ribbon development in west Connemara, County Galway Ireland.

Name

19th century antiquarian John O'Donovan documents a number of variants of the village, including Ballyconneely, Baile 'ic Conghaile, Ball ...

– ( / )

* Ballynahinch – ()

* Carna – ()

* Carraroe

Carraroe (in Irish, and officially, , meaning 'the red quarter') is a village in County Galway, Ireland, in the Irish-speaking region (Gaeltacht) of Connemara. It is known for its traditional fishing boats, the Galway Hookers. Its population ...

– ()

* Claddaghduff

Claddaghduff (derived from the Irish ''An Cladach Dubh'' meaning ''the black shore'') is a village in County Galway, Ireland. It is located northwest of Clifden, the gateway to Omey Island.

History

The village, now sparsely populated, overloo ...

– ()

* Cleggan

Cleggan () is a fishing village in County Galway, Ireland. The village lies 10 km (7 mi) northwest of Clifden and is situated at the head of Cleggan Bay.

A focal point of the village is the pier, built by Alexander Nimmo in 1822 an ...

– ()

* Clifden – ()

* Clonbur – ()

* Inverin – ()

* Kilkerren – ()

* Leenaun

Leenaun (), also Leenane, is a village and 1,845 acre townland in County Galway, Ireland, on the southern shore of Killary Harbour and the northern edge of Connemara.

Location

Leenaun is situated on the junction of the N59 road, and the R336 r ...

– ( / Leenane)

* Letterfrack

Letterfrack or Letterfrac () is a small village in the Connemara area of County Galway, Ireland. It was founded by Quakers in the mid-19th century. The village is south-east of Renvyle peninsula and north-east of Clifden on Barnaderg Bay an ...

– ()

* Lettermore

Lettermore () is a Gaeltacht village in County Galway, Ireland. It is also the name of an island, linked by road to the mainland, on which the village sits. The name comes from the Irish ''Leitir Móir'' meaning ''great rough hillside'' (''leitir ...

– ()

* Lettermullan

Lettermullen, ( or possibly "the hill with the mill"), is a small island and village on the coast of southern Connemara in County Galway, Ireland. It is about west of Galway city, at the far western end of Galway Bay, Lettermullen is the western ...

– ()

* Maum

An Mám (anglicized as Maum, or sometimes Maam) is a small village and its surrounding lands in Connemara, County Galway, Ireland.

Name

An Mám is Irish for "the pass" and as this is a Gaeltacht (principally Irish-speaking) area, the area's na ...

– (, also )

* Oughterard

Oughterard () is a small town on the banks of the Owenriff River close to the western shore of Lough Corrib in Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. The population of the town in 2016 was 1,318. It is located about northwest of Galway on the N59 ...

– ()

* Recess – ()

* Renvyle – ()

* Rosmuc

Rosmuc or Ros Muc, sometimes anglicised as Rosmuck, is a village in the Conamara Gaeltacht of County Galway, Ireland. It lies halfway between the town of Clifden and the city of Galway. Irish is the predominant spoken language in the area, with ...

– ()

* Rossaveal

Rossaveal or Rossaveel ( or ''Ros a' Mhíl'') is a Gaeltacht village and townland in the Connemara area of County Galway, Ireland. It is the main ferry port for the Aran Islands in Galway Bay. It is about from Galway city.

The Irish name ''Ros ...

– ()

* Roundstone – ()

* Spiddal

Spiddal ( ga, An Spidéal , meaning 'the hospital') is a village on the shore of Galway Bay in County Galway, Ireland. It is west of Galway city, on the R336 road. It is on the eastern side of the county's Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking area) an ...

– ()

Islands

*Omey Island

Omey Island ( ga, Iomaidh) is a tidal island situated near Claddaghduff on the western edge of Connemara in County Galway, Ireland. From the mainland the island is almost hidden. It is possible to drive or walk across a large sandy strand to t ...

– ()

* Inishbofin – () has been home to fishermen, farmers, exiled monks and fugitive pirates for over 6,000 years and today the island supports a population of 200 full-time residents.

Notable people

* Seán 'ac Dhonncha (1919–1996), sean-nós singer * Nan Tom Teaimín de Búrca, a local sean-nós singer, lives near Carna in Rusheenamanagh * Róisín Elsafty, sean-nós singer *John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), known professionally as John Ford, was an American film director and naval officer. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of his generation. He ...

, the American film director, and winner of 4 Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

, whose real name was Seán O'Feeney, was the son of John Augustine Feeney from An Spidéal

Spiddal ( ga, An Spidéal , meaning 'the hospital') is a village on the shore of Galway Bay in County Galway, Ireland. It is west of Galway city, on the R336 road. It is on the eastern side of the county's Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking area) an ...

, and directed the classic film ''The Quiet Man

''The Quiet Man'' is a 1952 American romantic comedy-drama film directed by John Ford. It stars John Wayne, Maureen O'Hara, Barry Fitzgerald, Ward Bond and Victor McLaglen. The screenplay by Frank S. Nugent was based on a 1933 ''Saturday Ev ...

'' in nearby Cong, County Mayo.

* Máire Geoghegan-Quinn is an Irish politician, and was the former European Commissioner for Research, Innovation and Science was born in Carna.

*Claire Hanna

Claire Aisling Hanna (born 19 June 1980) is an Irish Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) politician from Northern Ireland. In December 2019, she was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Belfast South in the House of Commons. Previous ...

, SDLP MP in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

was born here.

* J. Bruce Ismay

Joseph Bruce Ismay (; 12 December 1862 – 17 October 1937) was an English businessman who served as chairman and managing director of the White Star Line. In 1912, he came to international attention as the highest-ranking White Star official t ...

, Chairman of the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

, which owned the ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, Unite ...

'', lived for part of his later life in his lodge in Connemara. Ismay was on board the Titanic when it sank but was one of the survivors."J. Bruce Ismay, 74, Titanic Survivor. Ex-Head of White Star Line Who Retired After Sea Tragedy Dies in London". ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''. 19 October 1937. "Joseph Bruce Ismay, former chairman of the White Star Line and a survivor of the Titanic disaster in 1912, died here last night. He was 74 years old."

* Seán Mannion, a professional boxer who fought for the WBA, was born in Rosmuc

Rosmuc or Ros Muc, sometimes anglicised as Rosmuck, is a village in the Conamara Gaeltacht of County Galway, Ireland. It lies halfway between the town of Clifden and the city of Galway. Irish is the predominant spoken language in the area, with ...

.

* Richard Martin, MP, known as "Humanity Dick", was born in Ballynahinch Castle, Ballynahinch and represented Galway in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

.

* Michael Morris, 3rd Baron Killanin

Michael Morris, 3rd Baron Killanin, (30 July 1914 – 25 April 1999) was an Irish journalist, author, sports official, and the sixth President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). He succeeded his uncle as Baron Killanin in the Peer ...

, was president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and lived at the family seat in Spiddal.

* Patrick Nee, Rosmuc

Rosmuc or Ros Muc, sometimes anglicised as Rosmuck, is a village in the Conamara Gaeltacht of County Galway, Ireland. It lies halfway between the town of Clifden and the city of Galway. Irish is the predominant spoken language in the area, with ...

-born Irish-American organized crime

The Irish Mob (also known as the Irish mafia or Irish organized crime) is a collective of organized crime syndicates composed of ethnic Irish members which operate primarily in Ireland, the United States, Canada and Australia, and have been in ...

figure turned Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

, senior member of the Mullen Gang, and mastermind of an enormous arms trafficking

Arms trafficking or gunrunning is the illicit trade of contraband small arms and ammunition, which constitutes part of a broad range of illegal activities often associated with transnational criminal organizations. The illegal trade of small arm ...

ring to the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish re ...

from bases in Charlestown, South Boston

South Boston is a densely populated neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, located south and east of the Fort Point Channel and abutting Dorchester Bay. South Boston, colloquially known as Southie, has undergone several demographic transformat ...

, and Gloucester, Massachusetts

Gloucester () is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, in the United States. It sits on Cape Ann and is a part of Massachusetts's North Shore. The population was 29,729 at the 2020 U.S. Census. An important center of the fishing industry and a ...

and which paid protection money

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from vi ...

to local crime boss

A crime boss, also known as a crime lord, Don, gang lord, gang boss, mob boss, kingpin, godfather, crime mentor or criminal mastermind, is a person in charge of a criminal organization.

Description

A crime boss typically has absolute or nearl ...

Whitey Bulger.

* Sorcha Ní Ghuairim

Sorcha Ní Ghuairim (11 October 1911 – 1976) was a teacher, writer, and sean-nós singer.

Life

Sorcha Ní Ghuairim was born in Roisín na Manach, Carna in the Connemara Gaeltacht in County Galway on 11 October 1911. Her parents were Mái ...

(1911–1976) was a teacher, writer of modern literature in Irish