Confederate government of Kentucky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Confederate government of Kentucky was a shadow government established for the

The Confederate government of Kentucky was a shadow government established for the

Kentucky's citizens were split regarding the issues central to the Civil War. The state had strong economic ties with

Kentucky's citizens were split regarding the issues central to the Civil War. The state had strong economic ties with

On November 18, 116 delegates from 68 counties met at the William Forst House in Russellville.Kleber, p. 222 Burnett was elected presiding officer. Fearing for the safety of the delegates, he first proposed postponing proceedings until January 8, 1862.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 13 Johnson convinced the majority of the delegates to continue. By the third day, the military situation was so tenuous that the entire convention had to be moved to a tower on the campus of Bethel Female College, a now-defunct institution in Hopkinsville.

The first item was ratification of an

On November 18, 116 delegates from 68 counties met at the William Forst House in Russellville.Kleber, p. 222 Burnett was elected presiding officer. Fearing for the safety of the delegates, he first proposed postponing proceedings until January 8, 1862.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 13 Johnson convinced the majority of the delegates to continue. By the third day, the military situation was so tenuous that the entire convention had to be moved to a tower on the campus of Bethel Female College, a now-defunct institution in Hopkinsville.

The first item was ratification of an

During the winter of 1861, Johnson tried to assert the legitimacy of the fledgling government but its jurisdiction extended only as far as the area controlled by the Confederate Army. Johnson came short of raising the 46,000 troops requested by the Confederate Congress. Efforts to levy taxes and to compel citizens to turn over their guns to the government were similarly unsuccessful. On January 3, 1862, Johnson requested a sum of $3 million ($ as of ) from the Confederate Congress to meet the provisional government's operating expenses.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 20 The Congress instead approved a sum of $2 million, the expenditure of which required approval of Secretary of War

During the winter of 1861, Johnson tried to assert the legitimacy of the fledgling government but its jurisdiction extended only as far as the area controlled by the Confederate Army. Johnson came short of raising the 46,000 troops requested by the Confederate Congress. Efforts to levy taxes and to compel citizens to turn over their guns to the government were similarly unsuccessful. On January 3, 1862, Johnson requested a sum of $3 million ($ as of ) from the Confederate Congress to meet the provisional government's operating expenses.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 20 The Congress instead approved a sum of $2 million, the expenditure of which required approval of Secretary of War

Prior to abandoning Bowling Green, Governor Johnson requested that Richard Hawes come to the city and help with the administration of the government, but Hawes was delayed due to a bout with

Prior to abandoning Bowling Green, Governor Johnson requested that Richard Hawes come to the city and help with the administration of the government, but Hawes was delayed due to a bout with

Proceedings of the convention establishing provisional government of Kentucky. Constitution of the provisional government. Letter of the governor to the president. President s message recommending the admission of Kentucky as a member of the confederate states

James Copeland, Walters State Community College {{Authority control .American Civil War 1861 establishments in Kentucky

Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

of Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...

by a self-constituted group of Confederate sympathizers during the American Civil War. The shadow government never replaced the elected government in Frankfort, which had strong Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''U ...

sympathies. Neither was it able to gain the whole support of Kentucky's citizens; its jurisdiction extended only as far as Confederate battle lines in the Commonwealth, which at its greatest extent in 1861 and early 1862 encompassed over half the state. Nevertheless, the provisional government was recognized by the Confederate States of America, and Kentucky was admitted to the Confederacy on December 10, 1861. Kentucky, the final state admitted to the Confederacy, was represented by the 13th (central) star on the Confederate battle flag

The flags of the Confederate States of America have a history of three successive designs during the American Civil War. The flags were known as the "Stars and Bars", used from 1861 to 1863; the "Stainless Banner", used from 1863 to 1865; and ...

.

Bowling Green, Kentucky

Bowling Green is a home rule-class city and the county seat of Warren County, Kentucky, United States. Founded by pioneers in 1798, Bowling Green was the provisional capital of Confederate Kentucky during the American Civil War. As of the ...

, was designated the Confederate capital of Kentucky at a convention in nearby Russellville. Due to the military situation in the state, the provisional government was exiled

''Exiled'' () is a 2006 Hong Kong action drama film produced and directed by Johnnie To, and starring Anthony Wong, Francis Ng, Nick Cheung, Josie Ho, Roy Cheung and Lam Suet, with special appearances by Richie Jen and Simon Yam. The acti ...

and traveled with the Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating i ...

for most of its existence. For a short time in the autumn of 1862, the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

controlled Frankfort, the only time a Union capital was captured by Confederate forces. During this occupation, General Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Western ...

attempted to install the provisional government as the permanent authority in the Commonwealth. However, Union General Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles— Shiloh and Per ...

ambushed the inauguration ceremony and drove the provisional government from the state for the final time. From that point forward, the government existed primarily on paper and was dissolved at the end of the war.

The provisional government elected two governors. George W. Johnson was elected at the Russellville Convention and served until his death at the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield ...

. Richard Hawes was elected to replace Johnson and served through the remainder of the war.

Background

Kentucky's citizens were split regarding the issues central to the Civil War. The state had strong economic ties with

Kentucky's citizens were split regarding the issues central to the Civil War. The state had strong economic ties with Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illi ...

cities such as Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylv ...

and Cincinnati while at the same time sharing many cultural, social, and economic links with the South. Unionist traditions were strong throughout the Commonwealth's history, especially in the east. With economic ties to both the North and the South, Kentucky had little to gain and much to lose from a war between the states. Additionally, many slaveholders felt that the best protection for slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was within the Union.

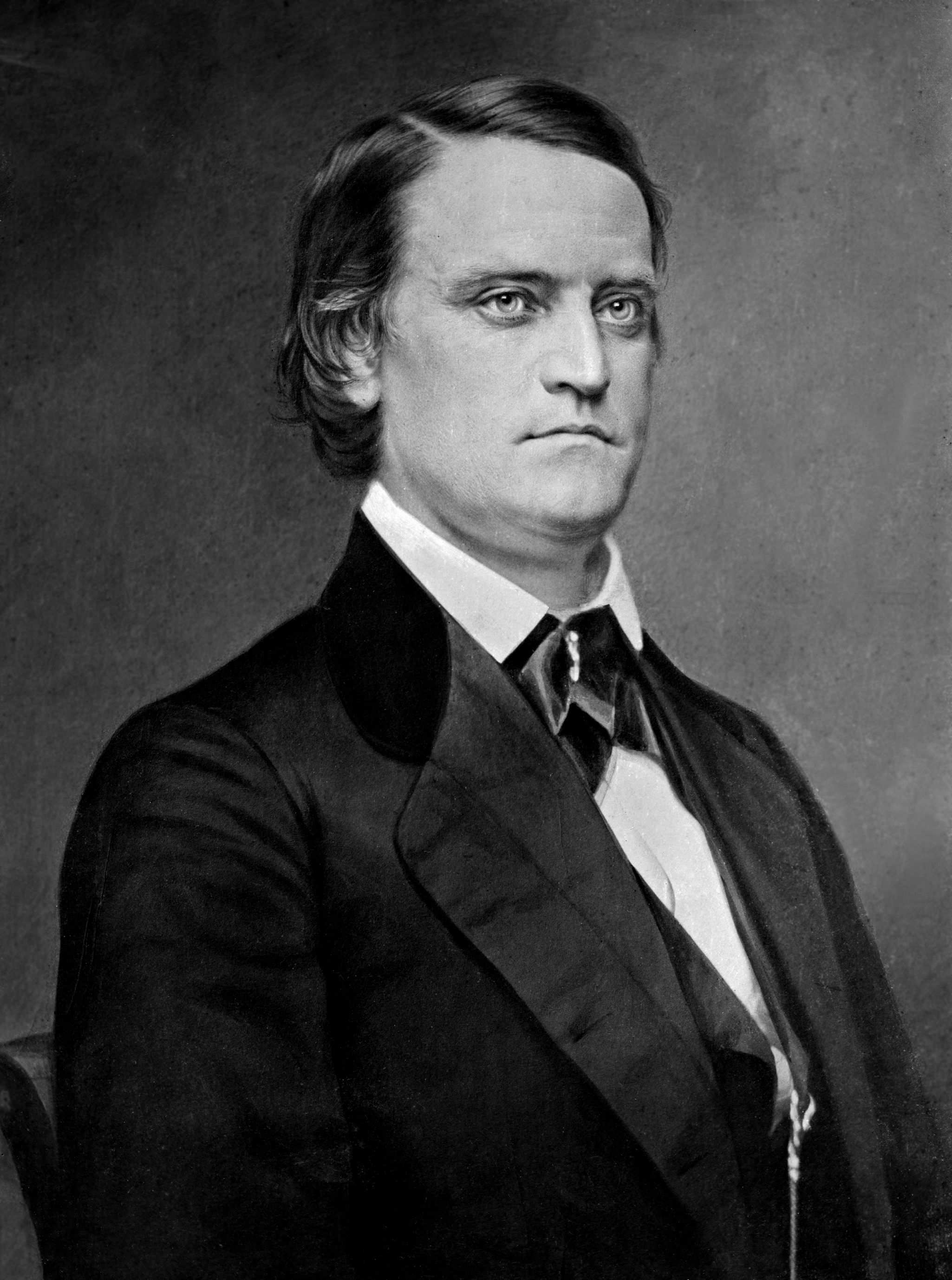

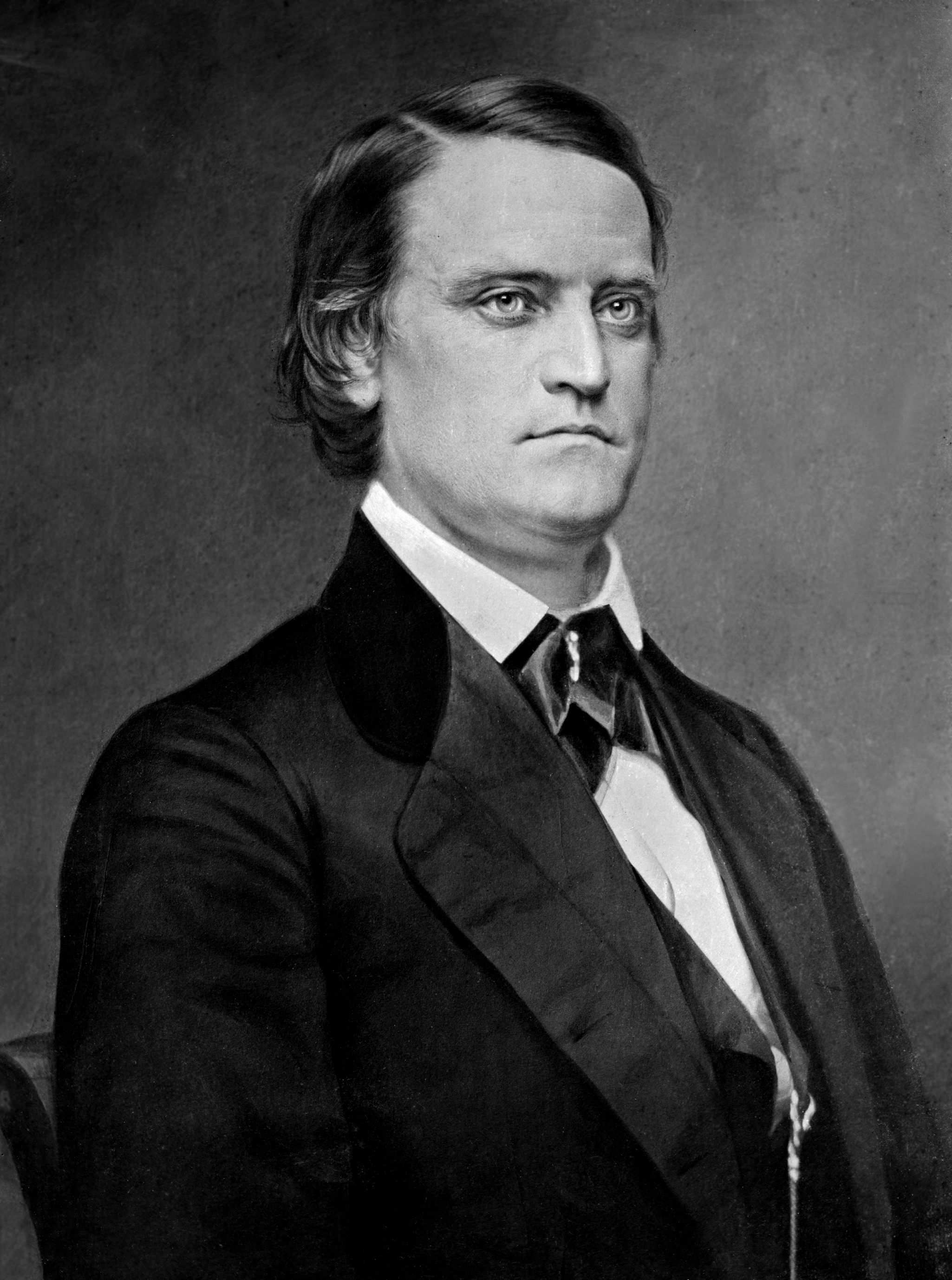

The presidential election of 1860 showed Kentucky's mixed sentiments when the state gave John Bell 45% of the popular vote, John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

36%, Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

18%, and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

less than 1%. Historian Allan Nevins interpreted the election results to mean that Kentuckians strongly opposed both secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics lea ...

and coercion against the secessionists. The majority coalition of Bell and Douglas supporters was seen as a solid moderate Unionist position that opposed precipitate action by extremists on either side.Nevins, pp. 129–130

The majority of Kentucky's citizens believed the state should be a mediator between the North and South. On December 9, 1860, Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin

Beriah Magoffin (April 18, 1815 – February 28, 1885) was the 21st Governor of Kentucky, serving during the early part of the Civil War. Personally, Magoffin adhered to a states' rights position, including the right of a state to secede from t ...

sent a letter to the other slave state governors, suggesting that they come to an agreement with the North that would include strict enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also known ...

, a division of common territories at the 37th parallel, a guarantee of free use of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

, and a Southern veto over slave legislation. Magoffin proposed a conference of slave states, followed by a conference of all the states to secure the concessions. Because of the escalating pace of events, neither conference was held.Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', pp. 6–7

Governor Magoffin called a special session of the Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in the ...

on December 27, 1860, to ask the legislators for a convention to decide the Commonwealth's course in the sectional conflict.Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', p. 7 The ''Louisville Morning Courier'' on January 25, 1861, articulated the position that the secessionists faced in the legislature, "Too much time has already been wasted. The historic moment once past, never returns. For us and for Kentucky, the time to act is NOW OR NEVER." The Unionists, on the other hand, were unwilling to surrender the fate of the state to a convention that might "in a moment of excitement, adopt the extreme remedy of secession." The Unionist position carried after many of the states rights' legislators, opposing the idea of immediate secession, voted against the convention. The assembly did, however, send six delegates to a February 4 Peace Conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of certain states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities and sign a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in the past include the foll ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

, and asked Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to call a national convention to consider potential resolutions to the secession crisis, including the Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator Joh ...

, proposed by Kentuckian John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as United ...

.Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', p. 8

As a result of the firing on Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

, President Lincoln sent a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

to Governor Magoffin requesting that the Commonwealth supply four regiments as its share of the overall request of 75,000 troops for the war.Harrison in ''Kentucky Governors'', pp. 82–84 Magoffin, a Confederate sympathizer, replied, "President Lincoln, Washington, D.C. I will send not a man nor a dollar for the wicked purpose of subduing my sister Southern states. B. Magoffin."Powell, p. 52 Both houses of the General Assembly met on May 7 and passed declarations of neutrality in the war, a position officially declared by Governor Magoffin on May 20.Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', p. 9

In a special congressional election held June 20, Unionist candidates won nine of Kentucky's ten congressional seats.Harrison in ''Kentucky's Civil War 1861–1865'', pp. 63–65 Confederate sympathizers won only the Jackson Purchase

The Jackson Purchase, also known as the Purchase Region or simply the Purchase, is a region in the U.S. state of Kentucky bounded by the Mississippi River to the west, the Ohio River to the north, and the Tennessee River to the east.

Jackson's ...

region, which was economically linked to Tennessee by the Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 1974 ...

and Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, ...

s.Kleber, p. 193 Believing defeat at the polls was certain, many Southern Rightists had boycotted the election; of the 125,000 votes cast, Unionists captured close to 90,000.Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', p. 11 Confederate sympathizers were dealt a further blow in the August 5 election for state legislators. This election resulted in veto-proof Unionist majorities of 76–24 in the House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air cond ...

and 27–11 in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the ...

. From then on, most of Magoffin's vetoes to protect southern interests were overridden in the General Assembly.

Historian Wilson Porter Shortridge made the following analysis:

With secession no longer considered a viable option, the pro-Confederate forces became the strongest supporters for neutrality. Unionists dismissed this as a front for a secessionist agenda. Unionists, on the other hand, struggled to find a way to move the large, moderate middle to a "definite and unqualified stand with the Washington government." The maneuvering between the two reached a decisive point on September 3 when Confederate forces were ordered from Tennessee to the Kentucky towns of Hickman

Hickman or Hickmann may refer to:

People

* Hickman (surname), notable people with the surname Hickman or Hickmann

* Hickman Ewing, American attorney

* Hickman Price (1911–1989), assistant secretary in the United States Department of Commerce ...

and Columbus. Union forces responded by occupying Paducah.

On September 11, the legislature passed a resolution instructing Magoffin to order the Confederate forces (but not the Union forces) to leave the state. The Governor vetoed the resolution, but the General Assembly overrode his veto, and Magoffin gave the order. The next week, the assembly officially requested the assistance of the Union and asked the governor to call out the state militia to join the Federal forces. Magoffin also vetoed this request. Again the assembly overrode his veto and Magoffin acquiesced.

Formation

A pro-Confederate peace meeting, with Breckinridge as a speaker, was scheduled for September 21. Unionists feared the meeting would lead to actual military resistance, and dispatched troops from Camp Dick Robinson to disband the meeting and arrest Breckinridge. Breckinridge, as well as many other state leaders identified with the secessionists, fled the state. These leaders eventually served as the nucleus for a group that would create a shadow government for Kentucky. In his October 8 "Address to the People of Kentucky," Breckinridge declared, "TheUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

no longer exists. The Union is dissolved."

On October 29, 1861, 63 delegates representing 34 counties met at Russellville to discuss the formation of a Confederate government for the Commonwealth.Brown, p. 83 Despite its defeats at the polls, this group believed that the Unionist government in Frankfort did not represent the will of the majority of Kentucky's citizens. Trigg County's Henry Burnett was elected chairman of the proceedings. Scott County farmer George W. Johnson chaired the committee that wrote the convention's final report and introduced some of its key resolutions. The report called for a sovereignty convention to sever ties with the Federal government. Both Breckinridge and Johnson served on the Committee of Ten that arranged the convention.

On November 18, 116 delegates from 68 counties met at the William Forst House in Russellville.Kleber, p. 222 Burnett was elected presiding officer. Fearing for the safety of the delegates, he first proposed postponing proceedings until January 8, 1862.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 13 Johnson convinced the majority of the delegates to continue. By the third day, the military situation was so tenuous that the entire convention had to be moved to a tower on the campus of Bethel Female College, a now-defunct institution in Hopkinsville.

The first item was ratification of an

On November 18, 116 delegates from 68 counties met at the William Forst House in Russellville.Kleber, p. 222 Burnett was elected presiding officer. Fearing for the safety of the delegates, he first proposed postponing proceedings until January 8, 1862.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 13 Johnson convinced the majority of the delegates to continue. By the third day, the military situation was so tenuous that the entire convention had to be moved to a tower on the campus of Bethel Female College, a now-defunct institution in Hopkinsville.

The first item was ratification of an ordinance of secession

An Ordinance of Secession was the name given to multiple resolutions drafted and ratified in 1860 and 1861, at or near the beginning of the Civil War, by which each seceding Southern state or territory formally declared secession from the United ...

, which proceeded in short order. Next, being unable to flesh out a complete constitution and system of laws, the delegates voted that "the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princi ...

and laws of Kentucky, not inconsistent with the acts of this Convention, and the establishment of this Government, and the laws which may be enacted by the Governor and Council, shall be the laws of this state."Harrison in ''Register'', p. 14 The delegates proposed a provisional government to consist of a legislative council of ten members (one from each Kentucky congressional district); a governor, who had the power to appoint judicial and other officials; a treasurer; and an auditor.Brown, p. 84 The delegates designated Bowling Green (then under the control of Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, fi ...

) as the Confederate State capital, but had the foresight to provide for the government to meet anywhere deemed appropriate by the council and governor. The convention adopted a new state seal, an arm wearing mail

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal sys ...

with a star, extended from a circle of twelve other stars.

The convention unanimously elected Johnson as governor. Horatio F. Simrall was elected lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, but soon fled to Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Missis ...

to escape Federal authorities.Powell, p. 116 Robert McKee, who had served as secretary of both conventions, was appointed secretary of state.Brown, p. 85 Theodore Legrand Burnett was elected treasurer, but resigned on December 17 to accept a position in the Confederate Congress

The Confederate States Congress was both the provisional and permanent legislative assembly of the Confederate States of America that existed from 1861 to 1865. Its actions were for the most part concerned with measures to establish a new nat ...

. He was replaced by Warren County native John Quincy Burnham. The position of auditor was first offered to former Congressman Richard Hawes, but Hawes declined to continue his military service under Humphrey Marshall Humphrey Marshall may refer to:

*Humphry Marshall (1722–1801), botanist

* Humphrey Marshall (general) (1812–1872), Confederate general in the American Civil War

*Humphrey Marshall (politician)

Humphrey Marshall (1760 – July 3, 1841) w ...

.Kleber, pp. 418–419 In his stead, the convention elected Josiah Pillsbury, also of Warren County. The legislative council elected Willis Benson Machen as its president.

On November 21, the day following the convention, Johnson wrote Confederate president Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

to request Kentucky's admission to the Confederacy. Burnett, William Preston, and William E. Simms were chosen as the state's commissioners to the Confederacy.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 15 For reasons unexplained by the delegates, Dr. Luke P. Blackburn, a native Kentuckian living in Mississippi, was invited to accompany the commissioners to Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. Though Davis had reservations about circumvention of the elected General Assembly in forming the Confederate government, he concluded that Johnson's request had merit, and on November 25, recommended Kentucky for admission to the Confederacy.Brown, p. 87 Kentucky was admitted to the Confederacy on December 10, 1861.

Activity

On November 26, 1861, Governor Johnson issued an address to the citizens of the Commonwealth blamingabolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

s for the breakup of the United States. He asserted his belief that the Union and Confederacy were forces of equal strength, and that the only solution to the war was a free trade agreement between the two sovereign nations. He further announced his willingness to resign as provisional governor if the Kentucky General Assembly would agree to cooperate with Governor Magoffin. Magoffin himself denounced the Russellville Convention and the provisional government, stressing the need to abide by the will of the majority of the Commonwealth's citizens.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 16

During the winter of 1861, Johnson tried to assert the legitimacy of the fledgling government but its jurisdiction extended only as far as the area controlled by the Confederate Army. Johnson came short of raising the 46,000 troops requested by the Confederate Congress. Efforts to levy taxes and to compel citizens to turn over their guns to the government were similarly unsuccessful. On January 3, 1862, Johnson requested a sum of $3 million ($ as of ) from the Confederate Congress to meet the provisional government's operating expenses.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 20 The Congress instead approved a sum of $2 million, the expenditure of which required approval of Secretary of War

During the winter of 1861, Johnson tried to assert the legitimacy of the fledgling government but its jurisdiction extended only as far as the area controlled by the Confederate Army. Johnson came short of raising the 46,000 troops requested by the Confederate Congress. Efforts to levy taxes and to compel citizens to turn over their guns to the government were similarly unsuccessful. On January 3, 1862, Johnson requested a sum of $3 million ($ as of ) from the Confederate Congress to meet the provisional government's operating expenses.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 20 The Congress instead approved a sum of $2 million, the expenditure of which required approval of Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin

Judah Philip Benjamin, QC (August 6, 1811 – May 6, 1884) was a United States senator from Louisiana, a Cabinet officer of the Confederate States and, after his escape to the United Kingdom at the end of the American Civil War, an English ...

and President Davis. Much of the provisional government's operating capital was probably provided by Kentucky congressman Eli Metcalfe Bruce, who made a fortune from varied economic activities throughout the war.

The council met on December 14 to appoint representatives to the Confederacy's unicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multic ...

provisional congress.Brown, p. 88 Those appointed would serve for only two months, as the provisional congress was replaced with a permanent bicameral legislature on February 17, 1862. Kentucky was entitled to two senators and 12 representatives in the permanent Confederate Congress.Harrison in ''Register'', p. 22 The usual day for general elections being passed, Governor Johnson and the legislative council set election day for Confederate Kentucky on January 22. Voters were allowed to vote in whichever county they occupied on election day, and could cast a general ballot for all positions. In an election that saw military votes outnumber civilian ones, only four of the provisional legislators were elected to seats in the Confederate House of Representatives. One provisional legislator, Henry Burnett, was elected to the Confederate Senate.

The provisional government took other minor actions during the winter of 1861. An act was passed to rename Wayne County to Zollicoffer County in honor of Felix Zollicoffer, who died at the Battle of Mill Springs.Brown, p. 89 Local officials were appointed in areas controlled by Confederate forces, including many justices of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sam ...

. When the Confederate government eventually disbanded, the legality of marriages performed by these justices was questioned, but eventually upheld.

Withdrawal from Kentucky and death of Governor Johnson

Following Ulysses S. Grant's victory at theBattle of Fort Henry

The Battle of Fort Henry was fought on February 6, 1862, in Stewart County, Tennessee, during the American Civil War. It was the first important victory for the Union and Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Western Theater.

On February 4 a ...

, General Johnston withdrew from Bowling Green into Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to t ...

on February 7, 1862. A week later, Governor Johnson and the provisional government followed. On March 12, the '' New Orleans Picayune'' reported that "the capital of Kentucky snow being located in a Sibley tent."

Governor Johnson, despite his presumptive official position, his age (50), and a crippled arm,Kleber, p. 473 volunteered to serve under Breckinridge and Colonel Robert P. Trabue at the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield ...

. On April 7, Johnson was severely wounded in the thigh and abdomen, and lay on the battlefield until the following day. Johnson was recognized and helped by acquaintance and fellow Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, Alexander McDowell McCook

Alexander McDowell McCook (April 22, 1831June 12, 1903) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War.

Early life

McCook was born in Columbiana County, Ohio. A Scottish family, the McCooks were prominent ...

, a Union general. However, Johnson died aboard the Union hospital ship ''Hannibal'', and the provisional government of Kentucky was left leaderless.

Richard Hawes as governor

Prior to abandoning Bowling Green, Governor Johnson requested that Richard Hawes come to the city and help with the administration of the government, but Hawes was delayed due to a bout with

Prior to abandoning Bowling Green, Governor Johnson requested that Richard Hawes come to the city and help with the administration of the government, but Hawes was delayed due to a bout with typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

.Harrison in ''Kentucky's Civil War 1861–1865'', pp. 90–91 Following Johnson's death, the provisional government elected Hawes, who was still recovering from his illness, as governor.Harrison in ''Kentucky Governors'', pp. 85–88 Following his recovery, Hawes joined the government in Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth is a city in and the county seat of Alcorn County, Mississippi, Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,573 at the 2010 census. Its ZIP codes are 38834 and 38835. It lies on the state line with Tennessee.

Histor ...

, and took the oath of office on May 31.Brown, p. 93

During the summer of 1862, word began to spread through the Army of Tennessee that Generals Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith

General Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory and the Indi ...

were planning an invasion of Kentucky. The legislative council voted to endorse the invasion plan, and on August 27, Governor Hawes was dispatched to Richmond to favorably recommend it to President Davis. Davis was non-committal, but Bragg and Smith proceeded, nonetheless.

On August 30, Smith commanded one of the most complete Confederate victories of the war against an inexperienced Union force at the Battle of Richmond

The Battle of Richmond, Kentucky, fought August 29–30, 1862, was one of the most complete Confederate victories in the war by Major General Edmund Kirby Smith against Union major general William "Bull" Nelson's forces, which were defending ...

.Kleber, pp. 772–773 Bragg also won a decisive victory at the September 13 Battle of Munfordville, but the delay there cost him the larger prize of Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, which Don Carlos Buell moved to occupy on September 25.Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', p. 46 Having lost Louisville, Bragg spread his troops into defensive postures in the central Kentucky cities of Bardstown, Shelbyville and Danville and waited for something to happen, a move that historian Kenneth W. Noe called a "stupendously illogical decision".Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', p. 48Noe, p. 124

Meanwhile, the leaders of Kentucky's Confederate government had remained in Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020 ...

, awaiting Governor Hawes' return. They finally departed on September 18, and caught up with Bragg and Smith in Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, Fayette County. By population, it is the List of cities in Kentucky, second-largest city in Kentucky and List of United States cities by popul ...

on October 2. Bragg had been disappointed with the number of soldiers volunteering for Confederate service in Kentucky; wagon loads of weapons that had been shipped to the Commonwealth to arm the expected enlistees remained unissued.Harrison in ''The Civil War in Kentucky'', p. 47''Encyclopedia Americana'', p. 407 Desiring to enforce the Confederate Conscription Act to boost recruitment, Bragg decided to install the provisional government in the recently captured state capital of Frankfort. On October 4, 1862, Hawes was inaugurated as governor by the Confederate legislative council. In the celebratory atmosphere of the inauguration ceremony, however, the Confederate forces let their guard down, and were ambushed and forced to retreat by Buell's artillery.Powell, p. 115''Encyclopedia Americana'', p. 707

Decline and dissolution

Following theBattle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive (Kentucky Campaign) during the ...

, the provisional government left Kentucky for the final time. Displaced from their home state, members of the legislative council dispersed to places where they could make a living or be supported by relatives until Governor Hawes called them into session.Brown, p. 96 Scant records show that on December 30, 1862, Hawes summoned the council, auditor, and treasurer to his location at Athens, Tennessee

Athens is the county seat of McMinn County, Tennessee, United States and the principal city of the Athens Micropolitan Statistical Area has a population of 53,569. The city is located almost equidistantly between the major cities of Knoxville a ...

for a meeting on January 15, 1863. Hawes himself unsuccessfully lobbied President Davis to remove Hawes' former superior, Humphrey Marshall, from command.Brown, pp. 96–97 On March 4, Hawes told Davis by letter that "our cause is steadily on the increase" and assured him that another foray into the Commonwealth would produce better results than the first had.Brown, p. 97

The government's financial woes also continued. Hawes was embarrassed to admit that neither he nor anyone else seemed to know what became of approximately $45,000 that had been sent from Columbus to Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the County seat, seat of Shelby County, Tennessee, Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 Uni ...

during the Confederate occupation of Kentucky. Another major blow was Davis' 1864 decision not to allow Hawes to spend $1 million that had been secretly appropriated in August 1861 to help Kentucky maintain its neutrality. Davis reasoned that the money could not be spent for its intended purpose, since Kentucky had already been admitted to the Confederacy.

Late in the war, the provisional government existed mostly on paper. However, in the summer of 1864, Colonel R. A. Alston of the Ninth Tennessee Cavalry requested Governor Hawes' assistance in investigating crimes allegedly committed by Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825 – September 4, 1864) was an American soldier who served as a Confederate general in the American Civil War of 1861–1865.

In April 1862, Morgan raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment (CSA) and fought in ...

during his latest raid into Kentucky. Hawes never had to act on the request, however, as Morgan was suspended from command on August 10 and killed by Union troops on September 4, 1864.

There is no documentation detailing exactly when Kentucky's provisional government ceased operation. It is assumed to have dissolved upon the conclusion of the Civil War.

See also

*Border states (Civil War)

In the context of the American Civil War (1861–65), the border states were slave states that did not secede from the Union. They were Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, and after 1863, the new state of West Virginia. To their north t ...

*Confederate government of Missouri

The Confederate government of Missouri was a continuation in exile of the government of pro- Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson. It existed until General E. Kirby Smith surrendered all Confederate troops west of the Mississippi River a ...

, one of two rival state governments in Missouri

*Restored Government of Virginia

The Restored (or Reorganized) Government of Virginia was the Unionist government of Virginia during the American Civil War (1861–1865) in opposition to the government which had approved Virginia's seceding from the United States and join ...

, one of two rival state governments in Virginia

* Confederate government of West Virginia, Richmond's support in West Virginia

*Kentucky in the American Civil War

Kentucky was a border state of key importance in the American Civil War. It officially declared its neutrality at the beginning of the war, but after a failed attempt by Confederate General Leonidas Polk to take the state of Kentucky f ...

*Upland South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econo ...

* Western Theater of the American Civil War

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Proceedings of the convention establishing provisional government of Kentucky. Constitution of the provisional government. Letter of the governor to the president. President s message recommending the admission of Kentucky as a member of the confederate states

James Copeland, Walters State Community College {{Authority control .American Civil War 1861 establishments in Kentucky

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...

Government of Kentucky

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...

American Civil War

Kentucky

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to ...