Columbia, Pennsylvania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Columbia, formerly

English

English

* Columbia Market House * First National Bank Museum * Wright's Ferry Mansion * Bachman and Forry Tobacco Warehouse * Columbia Wagon Works * Old Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge * Manor Street Elementary School *

Turkey Hill Experience

ColumbiaPaOnline.com

Columbia Historic Preservation Society

Rivertownes PA USA: Columbia, Marietta, Wrightsville

Richard Edling

"Underground Railway"

at PHMC website

''Columbia Spy''

community blog

"Columbia Talk"

blog {{authority control 1788 establishments in Pennsylvania Boroughs in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Populated places established in 1788 Pennsylvania populated places on the Susquehanna River Populated places on the Underground Railroad

Wright's Ferry

Wright's Ferry was a Pennsylvania Colony settlement established by John Wright in 1726, that grew up around the site of an important Inn and Pub anchoring the eastern end of a popular animal powered ferry (1730–1901) and now a historic part of ...

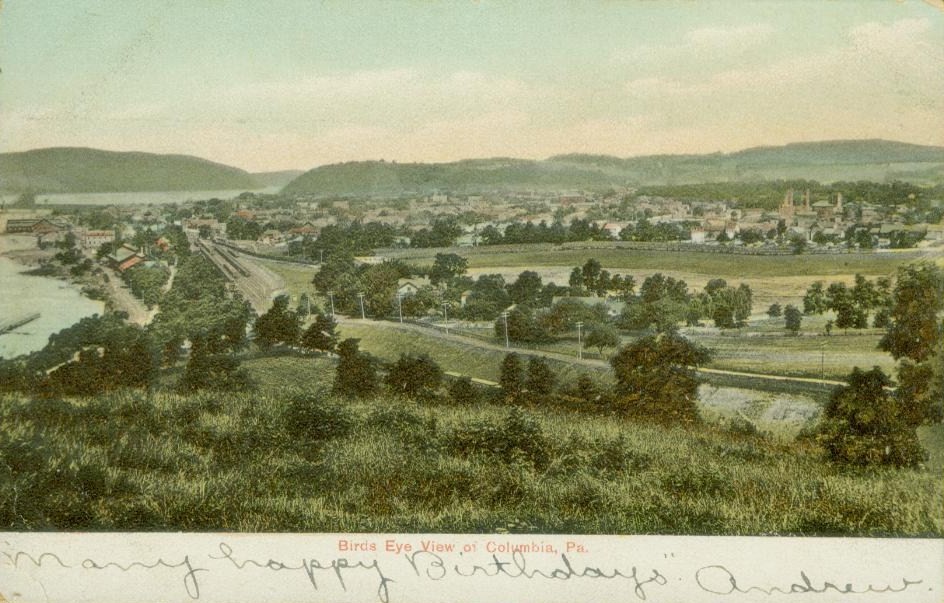

, is a borough (town) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

Lancaster County (; Pennsylvania Dutch: Lengeschder Kaundi), sometimes nicknamed the Garden Spot of America or Pennsylvania Dutch Country, is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is located in the south central part of Pennsylvania ...

, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 10,222. It is southeast of Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in P ...

, on the east (left) bank of the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the U ...

, across from Wrightsville and York County and just south of U.S. Route 30

U.S. Route 30 or U.S. Highway 30 (US 30) is an east–west main route in the system of the United States Numbered Highways, with the highway traveling across the northern tier of the country. With a length of , it is the third longest ...

.

The settlement was founded in 1726 by Colonial English Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

from Chester County, led by entrepreneur and evangelist John Wright. Establishment of the eponymous Wright's Ferry, the first commercial Susquehanna crossing in the region, inflamed territorial conflict with neighboring Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean ...

but brought growth and prosperity to the small town, which was just a few votes shy of becoming the new United States' capital. Though besieged for a short while by Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policie ...

destruction, Columbia remained a lively center of transport and industry throughout the 19th century, once serving as a terminus of the Pennsylvania Canal

The Pennsylvania Canal (or sometimes Pennsylvania Canal system) was a complex system of transportation infrastructure improvements including canals, dams, locks, tow paths, aqueducts, and viaducts. The Canal and Works were constructed and asse ...

. Later, however, the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The Financial contagion, ...

and 20th-century changes in economy and technology sent the borough into decline. It is notable today as the site of one of the world's few museums devoted entirely to horology

Horology (; related to Latin '; ; , interfix ''-o-'', and suffix ''-logy''), . is the study of the measurement of time. Clocks, watches, clockwork, sundials, hourglasses, clepsydras, timers, time recorders, marine chronometers, and atomic cl ...

.

History

18th century

Early history

The area around present-day Columbia was originally populated by Native American tribes, most notably theSusquehannock

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were Iroquoian Native Americans who lived in areas adjacent to the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, ranging from its upper reaches in the southern p ...

s, who migrated to the area between 1575 and 1600 after separating from the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

. They established villages just south of Columbia, in what is now Washington Boro, as well as claiming at least hunting lands as far south as Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean ...

and northern Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

.

First Western settlements

In 1724, John Wright, an EnglishQuaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, traveled to the Columbia area (then a part of Chester County) to explore the land and proselytize to a Native American tribe, the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentuck ...

, who had established a settlement along Shawnee Creek. Wright built a log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a less finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first generation home building by settlers.

Eur ...

nearby on a tract of land first granted to George Beale by William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

in 1699, and stayed for more than a year. The area was then known as "Shawanatown".

When Wright returned in 1726 with companions Robert Barber and Samuel Blunston, they began developing the area, Wright building a house about a hundred yards from the edge of the Susquehanna River in the area of today's South Second and Union streets. Susanna Wright later built Wright's Ferry Mansion, what is now the oldest existing house in Columbia, dating to 1738. She lived in this house with her brother James and his wife Rhoda, and possibly the first of their many children. The home is open for tours as a house museum and is located at Second and Cherry streets.

Robert Barber constructed a sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes (dimensi ...

in 1727 and later built a home near the river on the Washington Boro Pike, along what is now Route 441. The home still stands, across from the Columbia wastewater treatment plant

Wastewater treatment is a process used to remove contaminants from wastewater and convert it into an effluent that can be returned to the water cycle. Once returned to the water cycle, the effluent creates an acceptable impact on the environmen ...

, and is the second oldest in the borough (after Wright's Ferry Mansion).

Samuel Blunston constructed a mansion called Bellmont atop the hill next to North Second Street, near Chestnut Street, at the location of the present-day Rotary Park playground. Upon his death, Blunston willed the mansion to Susanna Wright, who had become a close friend. She lived there, occasionally visiting brother James, ministering to the Native Americans, and raising silkworms for the local silk industry, until her death in 1784 at the age of 87. The residence was demolished in the late 1920s to allow for construction of the Veterans Memorial Bridge.

In 1729, after Wright had petitioned William Penn's son to create a new county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposes Chambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

, the provincial government took land from Chester County to establish Lancaster County, the fourth county in Pennsylvania. County residents – Indians and colonists alike – regularly traveled to Wright's home to file papers and claims, seek government assistance and redress of issues, and register land deed

In common law, a deed is any legal instrument in writing which passes, affirms or confirms an interest, right, or property and that is signed, attested, delivered, and in some jurisdictions, sealed. It is commonly associated with transferring ...

s. The area was particularly attractive to Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch ( Pennsylvania Dutch: ), also known as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They emigrated primarily from German-sp ...

settlers. During this time, the town was called "Wright's Ferry".

Wright's Ferry

In 1730, John Wright was granted a patent to operate a ferry across the Susquehanna River, subsequently established (with Barber and Blunston) asWright's Ferry

Wright's Ferry was a Pennsylvania Colony settlement established by John Wright in 1726, that grew up around the site of an important Inn and Pub anchoring the eastern end of a popular animal powered ferry (1730–1901) and now a historic part of ...

. He also built a ferry house and a two-story log tavern

A tavern is a place of business where people gather to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food such as different types of roast meats and cheese, and (mostly historically) where travelers would receive lodging. An inn is a tavern that ...

on the eastern shore, north of Locust Street, on Front Street.

The ferry itself originally consisted of two dugout canoe

A dugout canoe or simply dugout is a boat made from a hollowed tree. Other names for this type of boat are logboat and monoxylon. ''Monoxylon'' (''μονόξυλον'') (pl: ''monoxyla'') is Greek – ''mono-'' (single) + '' ξύλον xylon'' (t ...

s fastened together with carriage and wagon wheels and drawn by cattle. Crossings could be a dangerous enterprise. When several oxen were moved at once, the canoeist guided a lead animal with a rope so that the others would follow; if, however, the lead animal became confused and started swimming in circles, the other animals followed until they tired and eventually drowned

Drowning is a type of suffocation induced by the submersion of the mouth and nose in a liquid. Most instances of fatal drowning occur alone or in situations where others present are either unaware of the victim's situation or unable to offer as ...

.

Typical fares in the 1700s were:

* Coach

Coach may refer to:

Guidance/instruction

* Coach (sport), a director of athletes' training and activities

* Coaching, the practice of guiding an individual through a process

** Acting coach, a teacher who trains performers

Transportation

* Coa ...

with four passengers, drawn by five horses – nine shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

s;

* Four-horse wagon – three shillings and nine pence;

* Man and horse – six pence

Fares were reduced in 1787 due to competition from Anderson's Ferry, located further upstream near Marietta. Wright's Ferry was located immediately south of the present-day Veterans Memorial Bridge along Route 462. In later years, Wright rented the ferry to others before finally selling it.

Traffic heading west from Lancaster, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sin ...

, and other nearby towns regularly traveled through Columbia, using the ferry to cross the Susquehanna. As traffic flow increased, the ferry grew, to the point of including canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the ter ...

s, raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water. It is usually of basic design, characterized by the absence of a hull. Rafts are usually kept afloat by using any combination of buoyant materials such as wood, sealed barrel ...

s, flatboat

A flatboat (or broadhorn) was a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with square ends used to transport freight and passengers on inland waterways in the United States. The flatboat could be any size, but essentially it was a large, sturdy tub with ...

s, and eventually steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

s; it became capable of handling Conestoga wagons and other large vehicles. Due to the volume of traffic, however, wagons, freight, supplies and people often became backed up, creating a waiting period of several days to cross the river. With 150 to 200 vehicles lined up on the Columbia side, ferrymen used chalk to number the wagons.

Cresap's War

Wright's Ferry was the first convenient crossing of the Susquehanna River in the region. At the time, however, southern Pennsylvania above the 40th parallel was claimed by theProvince of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryl ...

, which took especial interest in the rural area around the ferry. Fearing an influx of Pennsylvanian settlers that could weaken Maryland's influence, Maryland colonist Thomas Cresap

Colonel Thomas Cresap (17021790) was an English-born settler and trader in the states of Maryland and Pennsylvania. Cresap served Lord Baltimore as an agent in the Maryland–Pennsylvania boundary dispute that became known as Cresap's War. La ...

, under the aegis of Lord Baltimore, attempted to establish a competing ferry and a strong landholding presence around the Susquehanna. Pennsylvanians responded in kind; a violent attack on Cresap in October 1730 escalated the situation into a series of bitter (if not bloody) militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

skirmishes and heated legal battles. The situation was not fully resolved until a London peace agreement

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a sur ...

in 1738, which cooled the colonies' territorial dispute

A territorial dispute or boundary dispute is a disagreement over the possession or control of land between two or more political entities.

Context and definitions

Territorial disputes are often related to the possession of natural resources ...

and set the stage for the later codification of the Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, also called the Mason and Dixon line or Mason's and Dixon's line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (part of Virgini ...

.

Becoming Columbia

Samuel Wright, son of James and Rhoda Wright, was born on May 12, 1754. He eventually became the town proprietor and created a public grounds company to administer the land. Through his trusteeship, the town's firstwater distribution system

A water distribution system is a part of water supply network with components that carry potable water from a centralized treatment plant or wells to consumers to satisfy residential, commercial, industrial and fire fighting requirements.

Definit ...

(later the Columbia Water Company) was established, as well as the Washington Institute (the town's first school of higher learning) and Locust Street Park, located at what is now Locust Street and Route 462.

In the spring of 1788, Samuel Wright had the area surveyed and formally laid out the town into 160 building lots, which were distributed by lottery

A lottery is a form of gambling that involves the drawing of numbers at random for a prize. Some governments outlaw lotteries, while others endorse it to the extent of organizing a national or state lottery. It is common to find some degree of ...

at 15 shillings per ticket. "Adventurers", as purchasers were known, included speculators from many areas of the country. Wright and town citizens renamed the town "Columbia" in honor of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

in the hope of influencing the new U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

to select it as the nation's capital, a plan George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of t ...

favored; a formal proposal to do so was made in 1789. Unfortunately for the town, when Congress voted in 1790, the final tally was one vote short. Later, Columbia narrowly missed becoming the capital of Pennsylvania; Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in P ...

was chosen instead, being closer to the state's geographic center

In geography, the centroid of the two-dimensional shape of a region of the Earth's surface (projected radially to sea level or onto a geoid surface) is known as its geographic centre or geographical centre or (less commonly) gravitational centre. I ...

.

19th century

Expansion, construction, and transportation

English

English Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

, Scots-Irish Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

, freed African slaves

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of Africa in ancient times, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Indian Ocean sl ...

, German Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, and descendants of French Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

came to outnumber the first Quaker settlers within a generation.

Columbia became an incorporated borough in 1814, formed out of Hempfield Township. The same year, the world's longest covered bridge

A covered bridge is a timber- truss bridge with a roof, decking, and siding, which in most covered bridges create an almost complete enclosure. The purpose of the covering is to protect the wooden structural members from the weather. Uncovered wo ...

was built across the Susquehanna to Wrightsville, facilitating traffic flow across the river and reducing the need for the ferry. The bridge was long and wide, and had 54 stone pier

Seaside pleasure pier in Brighton, England. The first seaside piers were built in England in the early 19th century.">England.html" ;"title="Brighton, England">Brighton, England. The first seaside piers were built in England in the early 19th ...

s. After handling traffic across the Susquehanna for 18 years, it was destroyed by high water, ice, and severe weather in the winter of 1832. A replacement covered bridge, the Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge, was built within two years.

=Public works

= In February 1826, thePennsylvania state legislature

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvania ...

approved the package of legislation known as the Main Line of Public Works

The Main Line of Public Works was a package of legislation passed by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1826 to establish a means of transporting freight between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. It funded the construction of various long-proposed c ...

with the goal of connecting the width and breadth of Pennsylvania by the best and most reliable transportation known, water transport. The project started with the harder parts up the Juniata River

The Juniata River () is a tributary of the Susquehanna River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed August 8, 2011 in central Pennsylvania. The river is ...

and over the mountains being funded first. $300,000 in the funding was for the construction of a navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

that would be called the Pennsylvania Canal

The Pennsylvania Canal (or sometimes Pennsylvania Canal system) was a complex system of transportation infrastructure improvements including canals, dams, locks, tow paths, aqueducts, and viaducts. The Canal and Works were constructed and asse ...

along the Susquehanna's eastern shore to bypass rapids

Rapids are sections of a river where the river bed has a relatively steep gradient, causing an increase in water velocity and turbulence.

Rapids are hydrological features between a ''run'' (a smoothly flowing part of a stream) and a '' cascade' ...

and shallows and make the river navigable anywhere along its route. Also, as conceived, another canal would be dug from the terminus in Columbia to connect towns to the east with a terminus on the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, before e ...

at Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sin ...

.

Across the Alleghenies

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less develo ...

, another canal would connect the Allegheny Portage Railroad

The Allegheny Portage Railroad was the first railroad constructed through the Allegheny Mountains in central Pennsylvania, United States; it operated from 1834 to 1854 as the first transportation infrastructure through the gaps of the Allegheny ...

(crossing the mountains) to the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illi ...

and the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, ...

, ensuring the Port of Philadelphia would dominate inland trade and manufacturing in the exploding trans-Appalachian territories. It was a brave, far-looking, ambitious vision. Like the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing ...

which was completed in 1825, the very year the legislation package came to be filed, the overall scheme was envisioned when water transport

Maritime transport (or ocean transport) and hydraulic effluvial transport, or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people ( passengers) or goods (cargo) via waterways. Freight transport by sea has been widely used thro ...

was the fastest means of travel over any long distance, was the best way to ship heavy bulk goods or cumbersome loads—and was before railways came to the public eye and their technology had been refined enough to become working propositions. In 1836 there were probably fewer than six railways in the world.

In that reality, the navigations

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flow un ...

were finally begun in 1832 after several delays, the work went quickly and the Pennsylvania Canal

The Pennsylvania Canal (or sometimes Pennsylvania Canal system) was a complex system of transportation infrastructure improvements including canals, dams, locks, tow paths, aqueducts, and viaducts. The Canal and Works were constructed and asse ...

went into operation in 1833. It started at Columbia, stretching north to the junction of the Juniata River

The Juniata River () is a tributary of the Susquehanna River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed August 8, 2011 in central Pennsylvania. The river is ...

with the Susquehanna. The intent was that goods and travelers could use the canal system to go west from Columbia to Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also h ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The s ...

, and resent-dayWest Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

along the Juniata Division, or by taking the main Susquehanna northwards (Northern Division) to reach north-central Pennsylvania and into upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

.

When the reality met conception the plan broke. Engineering studies found no reasonably feasible way to provide enough water to keep an 82-mile canal to Philadelphia wet, much less support lock operations. When that was reported, the Pennsylvania Canal Commission came up with a new plan, one using the right of way authorized to build one of these newfangled railways that were making news. Their solution was the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad

Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad (P&CR) (1834) was one of the earliest commercial railroads in the United States, running from Philadelphia to Columbia, Pennsylvania, it was built by the Pennsylvania Canal Commission in lieu of a canal from Col ...

, one of the first common carrier commercial railways to operate in the United States. Double-tracked, it utilized two inclined plane

An inclined plane, also known as a ramp, is a flat supporting surface tilted at an angle from the vertical direction, with one end higher than the other, used as an aid for raising or lowering a load. The inclined plane is one of the six clas ...

cable railways at steep rises near either end, and except for bypasses of that older technology unneeded with more powerful locomotives, the P&CR trackage is still in use today, as it passed to the Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

in 1857, along with most of the Pennsylvania Canal.

Canal boats could often be seen at the Bruner coal wharf, operated by H.F. Bruner & Sons at North Front and Bridge streets. The canal was originally planned to extend south from Columbia on the east side of the river, but local property owners objected. Instead, a two-tiered towpath

A towpath is a road or trail on the bank of a river, canal, or other inland waterway. The purpose of a towpath is to allow a land vehicle, beasts of burden, or a team of human pullers to tow a boat, often a barge. This mode of transport w ...

was constructed along the south side of the bridge to transport boats across the river using horse and mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

teams. The boats then linked with the Susquehanna and Tidewater Canal along the western shore at Wrightsville. This part of the canal system, which afforded passage to Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

or the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal

The Chesapeake & Delaware Canal (C&D Canal) is a -long, -wide and -deep ship canal that connects the Delaware River with the Chesapeake Bay in the states of Delaware and Maryland in the United States.

In the mid‑17th century, mapmaker Aug ...

, opened

in 1840. Several years later, a small dam was constructed across the river to form a pool that allowed steamboats to tow the canal boats.

Canals could not be used in winter due to ice and floods, which caused damage that had to be repaired in the spring. These limitations, combined with an increase in railroad traffic, led to the decline of the canals. The Columbia Canal finally closed in 1901, the same year that Wright's Ferry ceased to operate.

During this time, Columbia also became a stop on the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

. Slaves seeking freedom were transported across the Susquehanna, fed and given supplies on their way north to other states and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world ...

. To slave hunters from the South, the slaves seemed to simply disappear, leading one hunter to declare that there "must be an underground railroad here."

Any idealistic view of abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

in Columbia is surely tested, however, by the occurrence of a significant race riot in 1834. The riot erupted in August of that year when white workers revolted against working alongside Black freedmen. Citing a document drafted by the rioters themselves, historian David Roediger

David R. Roediger (born July 13, 1952) is the Foundation Distinguished Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Kansas, where he has been since the fall of 2014. Previously, he was an American Kendrick C. Babcock Professor ...

explains that typical of other race riots of the period, white rioters feared "a plot by employers and abolitionists to open new trades to Blacks and 'to break down the distinctive barrier between the colors that the poor whites may gradually sink into the degraded condition of the Negroes - that, like them, they may be slaves and tools'." The rioters' declaration called for "colored freeholders" to be "singled out for removal from the Borough". The riot resulted in a large number of African American residents being forced from their homes and their property destroyed.

1834 saw the completion of another bridge spanning the river. Built by James Moore and John Evans at a cost of $157,300, this bridge, too, enjoyed the distinction of being the world's longest covered bridge. This year also saw construction of the first railway line linking Columbia and Philadelphia, which subsequently became part of the Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

. Named the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad

Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad (P&CR) (1834) was one of the earliest commercial railroads in the United States, running from Philadelphia to Columbia, Pennsylvania, it was built by the Pennsylvania Canal Commission in lieu of a canal from Col ...

, it officially opened in October 1834.

By 1852, regular rail transportation from Columbia to Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Harrisburg made the town the commercial center for the area halfway between the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US ...

s of Lancaster and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as ...

.

Columbia's role in the Civil War

In early 1863, as theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

raged, a number of local Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have of ...

citizens enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a regiment composed of black soldiers serving under white officers. The unit achieved fame in an assault on Fort Wagner

Fort Wagner or Battery Wagner was a beachhead fortification on Morris Island, South Carolina, that covered the southern approach to Charleston Harbor. It was the site of two American Civil War battles in the campaign known as Operations Agai ...

in South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. Stephen Swails, one of its members, may have been the first African-American officer commissioned during the Civil War. Other local citizens fought in various regiments of the United States Colored Troops

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments in the United States Army composed primarily of African-American ( colored) soldiers, although members of other minority groups also served within the units. They were first recruited durin ...

. Some of these veterans are buried in a cemetery located near Fifth Street.

On June 28, 1863, during the Gettysburg campaign, the replacement covered bridge was burned by Columbia residents and the Pennsylvania state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

to prevent Confederate soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

from entering Lancaster County. General Robert E. Lee had hoped to invade Harrisburg from the rear and move eastward to Lancaster and Philadelphia, and in the process destroy railroad yards and other facilities. Under General Jubal A. Early's command and following Lee's orders, General John B. Gordon was to place Lancaster and the surrounding farming area "under contribution" for the Confederate Army's war supplies and to attack Harrisburg from the east side of the river, while another portion of Lee's army advanced from the west side. General Early was given orders to burn the bridge but hoped instead to capture it, while Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''U ...

forces under the command of Colonel Jacob G. Frick and Major Granville O. Haller, hoping to save the bridge, were forced to burn it. Owners of the bridge petitioned Congress repeatedly for reimbursement well into the 1960s, but were denied payment.

With the Union Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confeder ...

hastening northward into Maryland and Pennsylvania, Robert E. Lee ordered his widely scattered forces to withdraw to Heidlersburg and Cashtown (not far from Gettysburg) to rendezvous with other contingents of the Confederate Army. The burning of the Columbia–Wrightsville Bridge thwarted one of Lee's goals for the invasion of Pennsylvania, and General Gordon later claimed the skirmish at Wrightsville reinforced the erroneous Confederate belief that the only defensive forces on hand were inefficient local militia, an attitude that carried over to the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union Army, Union and Confederate States Army, Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In t ...

.

Postwar growth

After the wartime bridge burning, atugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

, ''Columbia'', was used to tow canal boats across the river. In 1868, yet another replacement covered bridge was built, but was destroyed by a hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

in 1896. The next bridge, the Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge, was a steel open bridge which carried the tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad and a two-lane roadway for cars. It was dismantled for scrap by November 1964, but its stone piers, which supported the Civil War-era bridge, can still be seen today, running parallel to the Veterans Memorial Bridge on Route 462. The piers have become the site of present-day "Flames Across the Susquehanna" bridge-burning reenactments sponsored by Rivertownes PA USA.

In 1875, a new three-story grand town hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually ho ...

opened, featuring a second-floor auditorium

An auditorium is a room built to enable an audience to hear and watch performances. For movie theatres, the number of auditoria (or auditoriums) is expressed as the number of screens. Auditoria can be found in entertainment venues, community ...

that seated over 900 and was used as an opera house

An opera house is a theatre building used for performances of opera. It usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and building sets.

While some venues are constructed specifically fo ...

. The second floor's ceiling was higher than those of the first and third floors; each level contained 60 windows. The building also included office shops, council

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or natio ...

chambers, storerooms and market stalls. A bell tower

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell tow ...

, holding the town clock, crowned the building. The clock was visible from all over the borough, and its bell was audible throughout the surrounding countryside. The building was destroyed by fire in February 1947, but was rebuilt as a one-story municipal building that exists today.

Trolley service for the borough and surrounding area was established in 1893, allowing Columbians to take advantage of economic opportunities in Lancaster and other nearby towns. Between 1830 and 1900, the borough's population increased from 2,046 to 12,316.

Flourishing industry

By the mid-19th century, Columbia had become a busy transportation hub with its ferry, bridge, canal, railroad and wharves. It was a major shipping transfer point forlumber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, w ...

, coal, grain, pig iron, and people. Important industries of the time included warehousing, tobacco processing, iron production, clockmaking

A clockmaker is an artisan who makes and/or repairs clocks. Since almost all clocks are now factory-made, most modern clockmakers only repair clocks. Modern clockmakers may be employed by jewellers, antique shops, and places devoted strictly ...

, and boat building

Boat building is the design and construction of boats and their systems. This includes at a minimum a hull, with propulsion, mechanical, navigation, safety and other systems as a craft requires.

Construction materials and methods

Wood

W ...

. Prominent local companies included the Ashley and Bailey Silk Mill, the Columbia Lace Mill, and H.F. Bruner & Sons.

From about 1854 to 1900, an industrial complex existed in and around Columbia, Marietta and Wrightsville that included 11 anthracite iron

Anthracite iron or anthracite pig iron is the substance created by the smelting together of anthracite coal and iron ore, that is using anthracite coal instead of charcoal to smelt iron ores—and was an important historic advance in the late-1 ...

furnaces and related structures, as well as canal and railroad facilities servicing them. By 1887, that number had grown to 13 blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

s, all operating within a radius of Columbia. The furnaces, which produced pig iron, exemplified the technology of the day through their use of anthracite coal and hot blast

Hot blast refers to the preheating of air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. As this considerably reduced the fuel consumed, hot blast was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. ...

for smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a c ...

iron ore, a process that dominated the iron industry before the widespread use of coke as a fuel. Since northeastern Pennsylvania

Northeastern Pennsylvania (NEPA) is a geographic region of the U.S. state of Pennsylvania that includes the Pocono Mountains, the Endless Mountains, and the industrial cities of Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Pittston, Hazleton, Nanticoke, and Ca ...

was a rich source of anthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the high ...

coal, anthracite-fired furnaces using locally available iron ores were built throughout eastern Pennsylvania, helping to make the state a leader in iron production in the latter half of the 19th century. Lancaster County also became a leader in pig iron production during this time, with the river towns' complex of furnaces contributing significantly to its output.

20th century

Changes in the new century

By 1900, the town's population had grown to over 12,000, with a 50% increase from 1880 to 1900. Some of the items produced by its industries were silk goods, lace,pipe

Pipe(s), PIPE(S) or piping may refer to:

Objects

* Pipe (fluid conveyance), a hollow cylinder following certain dimension rules

** Piping, the use of pipes in industry

* Smoking pipe

** Tobacco pipe

* Half-pipe and quarter pipe, semi-circul ...

, laundry machinery, stoves, iron toys, flour, lumber, and wagons. By this time Wright's Ferry had ceased its operations, having been supplanted by rail and bridge traffic.

In 1930, yet another bridge, the Veterans Memorial Bridge, was opened to improve traffic flow across the Susquehanna. It first opened as a toll bridge

A toll bridge is a bridge where a monetary charge (or ''toll'') is required to pass over. Generally the private or public owner, builder and maintainer of the bridge uses the toll to recoup their investment, in much the same way as a toll road ...

; to avoid the toll, in the coldest winter months some daring motorists would cross on the firmly frozen river. Later that same decade, many of the city's brick sidewalk

A sidewalk ( North American English), pavement (British English), footpath in Australia, India, New Zealand and Ireland, or footway, is a path along the side of a street, highway, terminals. Usually constructed of concrete, pavers, brick, ston ...

s were converted to concrete; the bronze plaques of the concrete installers are still visible today.

Economic decline

The start of the 20th century brought economic challenge to Columbia as local industries declined. The lumber industry eventually disappeared as surrounding woodlands became depleted. As Chestnut Hill iron ores became scarce as well, the iron furnaces shut down. Eventually, thesteel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resist ...

rolling mills

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

also ceased operation. In 1906, the Pennsylvania Railroad opened a new facility in Enola, across the river from Harrisburg, which decreased the significance of Columbia's railroad. By 1920, the population had dropped over 10% to 10,836.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The Financial contagion, ...

accelerated Columbia's economic slide. The Pennsylvania Railroad's service to the north and the south was eliminated. World War II increased employment, but did not bring long-term prosperity to the borough.

By 1960, population had returned to its 1900 level. In 1965 a detailed study of Columbia's basic strengths and weaknesses was released, but its suggestions went mostly unheeded. The Wright's Ferry Bridge, which opened in 1972, only served to divert traffic around Columbia. The growth and prosperity experienced in some Lancaster County towns bypassed Columbia for the remainder of the 20th century. Although the United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of th ...

reported that as of the last year of the 20th century, the population of Columbia had been only 10,311 people, by 2010 this figure had grown to 10,400.

Demographics

As of the census of 2000, there were 10,311 people, 4,287 households, and 2,589 families residing in the borough. The population density was 4,227.8 people per square mile (1,631.6/km2). There were 4,595 housing units at an average density of 1,884.1 per square mile (727.1/km2). The racial makeup of the borough was 91.34%White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

, 4.42% Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have of ...

or African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

, 0.18% Native American, 0.41% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/ racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of Oce ...

, 1.70% from other races

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

, and 1.90% from two or more races. 4.49% of the population were Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties form ...

or Latino of any race.

There were 4,287 households, out of which 28.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.5% were married couples living together, 19.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.6% were non-families. 33.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the borough the population was spread out, with 24.3% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 29.2% from 25 to 44, 20.5% from 45 to 64, and 17.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.5 males.

The median income for a household in the borough was $32,385, and the median income for a family was $26,309. Males had a median income of $27,528 versus $22,748 for females. The per capita income for the borough was $14,626. About 11.5% of families and 11.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.3% of those under age 18 and 10.6% of those age 65 or over.

Geography

Columbia is located in western Lancaster County on the left (east) bank of theSusquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the U ...

. U.S. Route 30

U.S. Route 30 or U.S. Highway 30 (US 30) is an east–west main route in the system of the United States Numbered Highways, with the highway traveling across the northern tier of the country. With a length of , it is the third longest ...

, a four-lane freeway, passes through the northern side of the borough, leading east to the Lancaster area and west to York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as ...

. Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in P ...

, the state capital, is to the northwest, up the Susquehanna. Pennsylvania Route 462

Pennsylvania Route 462 (PA 462) is a east–west state route in York and Lancaster counties in central Pennsylvania. The western terminus is west of York, and the eastern terminus is east of Lancaster. At both ends, PA 462 terminates at ...

passes through the center of Columbia, leading east to Lancaster and west to York following the old route of US 30.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the borough of Columbia has an area of , of which , or 0.31%, are water.

It has a hot-summer humid continental climate

A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900, typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and freezin ...

(''Dfa''), and average monthly temperatures range from in January to in July. The hardiness zone

A hardiness zone is a geographic area defined as having a certain average annual minimum temperature, a factor relevant to the survival of many plants. In some systems other statistics are included in the calculations. The original and most wide ...

is 6b or 7a depending upon elevation.

Museums and historic sites

For over half a century, Columbia has been home to the headquarters of theNational Association of Watch and Clock Collectors

The National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, Inc. (NAWCC) is a nonprofit association of people who share a passion for collecting watches and clocks and studying horology (the art and science of time and timekeeping). The NAWCC's global m ...

(NAWCC), whose campus on Poplar Street includes a clock tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure which house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another build ...

, clock museum

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that Preservation (library and archival science), cares for and displays a collection (artwork), collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, culture, cultu ...

, library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

, research center, and "School of Horology

Horology (; related to Latin '; ; , interfix ''-o-'', and suffix ''-logy''), . is the study of the measurement of time. Clocks, watches, clockwork, sundials, hourglasses, clepsydras, timers, time recorders, marine chronometers, and atomic cl ...

," for training professional clock and watch repairers.

Other notable sites

* Columbia Historic District * Columbia Historic Preservation Society* Columbia Market House * First National Bank Museum * Wright's Ferry Mansion * Bachman and Forry Tobacco Warehouse * Columbia Wagon Works * Old Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge * Manor Street Elementary School *

Turkey Hill Experience

Schools

Schools in Columbia are part of the Columbia Borough School District.Elementary

* Park Elementary * Taylor Elementary * Columbia High SchoolSecondary

* Columbia Junior/Senior High * Our Lady of the AngelsHistorical

* Cherry Street School * Holy Trinity School * Manor Street School * Poplar Street School * St. Peter's School * Taylor School * Washington InstituteNotable people

* Ralph Heller Beittel, American composer * Amelia Reynolds Long, author * Edward C. Shannon, lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania * Stephen Atkins Swails, soldier and politician * Thomas Welsh, Civil War general * Suzanne Westenhoefer, comedian * Dean Young, poetReferences

* ''Columbia, the Gem,'' Bill Kloidt, Sr. 1994, Mifflin Press, Inc. * ''East of Gettysburg, A Gray Shadow Crosses York County, PA,'' James McClure. 2003, York Daily Record/ York County Heritage Trust. . * ''Fire on the River, The Defense of the World's Longest Covered Bridge and How It Changed the Battle of Gettysburg,'' George Sheldon. 2006, Quaker Hills Press, Inc. , . * ''The Susquehanna,'' Carl Carmer. 1955, Rinehart & Company, Inc. Library of Congress catalog Card No.: 53-8227. * Town Historical Markers and Plaques provided by Columbia Borough and Rivertownes PA USA.Notes

External links

*ColumbiaPaOnline.com

Columbia Historic Preservation Society

Rivertownes PA USA: Columbia, Marietta, Wrightsville

Richard Edling

"Underground Railway"

at PHMC website

''Columbia Spy''

community blog

"Columbia Talk"

blog {{authority control 1788 establishments in Pennsylvania Boroughs in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Populated places established in 1788 Pennsylvania populated places on the Susquehanna River Populated places on the Underground Railroad