Cold War submarine-launched ballistic missiles of the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cold is the presence of low temperature, especially in the atmosphere. In common usage, cold is often a subjective perception. A lower bound to temperature is

Cold is the presence of low temperature, especially in the atmosphere. In common usage, cold is often a subjective perception. A lower bound to temperature is

In the United States from about 1850 till end of 19th century export of ice was second only to cotton. The first ice box was developed by Thomas Moore, a farmer from Maryland in 1810 to carry butter in an oval shaped wooden tub. The tub was provided with a metal lining in its interior and surrounded by a packing of ice. A rabbit skin was used as insulation. Moore also developed an ice box for domestic use with the container built over a space of which was filled with ice. In 1825, ice harvesting by use of a horse drawn ice cutting device was invented by Nathaniel J. Wyeth. The cut blocks of uniform size ice was a cheap method of food preservation widely practiced in the United States. Also developed in 1855 was a steam powered device to haul 600 tons of ice per hour. More innovations ensued. Devices using compressed air as a refrigerants were invented.

In the United States from about 1850 till end of 19th century export of ice was second only to cotton. The first ice box was developed by Thomas Moore, a farmer from Maryland in 1810 to carry butter in an oval shaped wooden tub. The tub was provided with a metal lining in its interior and surrounded by a packing of ice. A rabbit skin was used as insulation. Moore also developed an ice box for domestic use with the container built over a space of which was filled with ice. In 1825, ice harvesting by use of a horse drawn ice cutting device was invented by Nathaniel J. Wyeth. The cut blocks of uniform size ice was a cheap method of food preservation widely practiced in the United States. Also developed in 1855 was a steam powered device to haul 600 tons of ice per hour. More innovations ensued. Devices using compressed air as a refrigerants were invented.

* The National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado using a new technique, managed to chill a microscopic mechanical drum to 360 micro kelvins, making it the coldest object on record. Theoretically, using this technique, an object could be cooled to absolute zero.

* The coldest known temperature ever achieved is a state of matter called the

* The National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado using a new technique, managed to chill a microscopic mechanical drum to 360 micro kelvins, making it the coldest object on record. Theoretically, using this technique, an object could be cooled to absolute zero.

* The coldest known temperature ever achieved is a state of matter called the

File:Adelie_Penguins_on_iceberg.jpg,

Cold is the presence of low temperature, especially in the atmosphere. In common usage, cold is often a subjective perception. A lower bound to temperature is

Cold is the presence of low temperature, especially in the atmosphere. In common usage, cold is often a subjective perception. A lower bound to temperature is absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest limit of the thermodynamic temperature scale, a state at which the enthalpy and entropy of a cooled ideal gas reach their minimum value, taken as zero kelvin. The fundamental particles of nature have minimum vibratio ...

, defined as 0.00K on the Kelvin scale, an absolute thermodynamic temperature

Thermodynamic temperature is a quantity defined in thermodynamics as distinct from kinetic theory or statistical mechanics.

Historically, thermodynamic temperature was defined by Kelvin in terms of a macroscopic relation between thermodynamic w ...

scale. This corresponds to on the Celsius scale

The degree Celsius is the unit of temperature on the Celsius scale (originally known as the centigrade scale outside Sweden), one of two temperature scales used in the International System of Units (SI), the other being the Kelvin scale. The d ...

, on the Fahrenheit scale

The Fahrenheit scale () is a temperature scale based on one proposed in 1724 by the physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). It uses the degree Fahrenheit (symbol: °F) as the unit. Several accounts of how he originally defined h ...

, and on the Rankine scale

The Rankine scale () is an absolute scale of thermodynamic temperature named after the University of Glasgow engineer and physicist Macquorn Rankine, who proposed it in 1859.

History

Similar to the Kelvin scale, which was first proposed in 184 ...

.

Since temperature relates to the thermal energy held by an object or a sample of matter, which is the kinetic energy of the random motion of the particle constituents of matter, an object will have less thermal energy when it is colder and more when it is hotter. If it were possible to cool a system to absolute zero, all motion of the particles in a sample of matter would cease and they would be at complete rest in the classical sense. The object could be described as having zero thermal energy. Microscopically in the description of quantum mechanics, however, matter still has zero-point energy

Zero-point energy (ZPE) is the lowest possible energy that a quantum mechanical system may have. Unlike in classical mechanics, quantum systems constantly fluctuate in their lowest energy state as described by the Heisenberg uncertainty pri ...

even at absolute zero, because of the uncertainty principle.

Cooling

Cooling refers to the process of becoming cold, or lowering in temperature. This could be accomplished by removing heat from a system, or exposing the system to an environment with a lower temperature.Coolant

A coolant is a substance, typically liquid, that is used to reduce or regulate the temperature of a system. An ideal coolant has high thermal capacity, low viscosity, is low-cost, non-toxic, chemically inert and neither causes nor promotes corrosio ...

s are fluids used to cool objects, prevent freezing and prevent erosion in machines.

Air cooling

Air cooling is a method of dissipating heat. It works by expanding the surface area or increasing the flow of air over the object to be cooled, or both. An example of the former is to add cooling fins to the surface of the object, either by maki ...

is the process of cooling an object by exposing it to air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing for ...

. This will only work if the air is at a lower temperature than the object, and the process can be enhanced by increasing the surface area, increasing the coolant flow rate, or decreasing the mass of the object.

Another common method of cooling is exposing an object to ice

Ice is water frozen into a solid state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 degrees Celsius or Depending on the presence of impurities such as particles of soil or bubbles of air, it can appear transparent or a more or less opaq ...

, dry ice, or liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen—LN2—is nitrogen in a liquid state at low temperature. Liquid nitrogen has a boiling point of about . It is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquid air. It is a colorless, low viscosity liquid that is wide ...

. This works by conduction

Conductor or conduction may refer to:

Music

* Conductor (music), a person who leads a musical ensemble, such as an orchestra.

* ''Conductor'' (album), an album by indie rock band The Comas

* Conduction, a type of structured free improvisation ...

; the heat is transferred from the relatively warm object to the relatively cold coolant.

Laser cooling and magnetic evaporative cooling are techniques used to reach very low temperatures.

History

Early history

In ancient times, ice was not adopted for food preservation but used to cool wine which the Romans had also done. According toPliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

, Emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

invented the ice bucket to chill wines instead of adding it to wine to make it cold as it would dilute it.

Some time around 1700 BC Zimri-Lim, king of Mari Kingdom in northwest Iraq had created an "icehouse" called ''bit shurpin'' at a location close to his capital city on the banks of the Euphrates. In the 7th century BC the Chinese had used icehouses to preserve vegetables and fruits. During the Tang dynastic rule in China (618 -907 AD) a document refers to the practice of using ice that was in vogue during the Eastern Chou Dynasty

The Eastern Zhou (; zh, c=, p=Dōngzhōu, w=Tung1-chou1, t= ; 771–256 BC) was a royal dynasty of China and the second half of the Zhou dynasty. It was divided into two periods: the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States.

History

In 7 ...

(770 -256 BC) by 94 workmen employed for "Ice-Service" to freeze everything from wine to dead bodies.

Shachtman says that in the 4th century AD, the brother of the Japanese emperor Nintoku

, also known as was the 16th Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Due to his reputation for goodness derived from depictions in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, he is sometimes referred to as the .

While his existence ...

gave him a gift of ice from a mountain. The Emperor was so happy with the gift that he named the first of June as the "Day of Ice" and ceremoniously gave blocks of ice to his officials.

Even in ancient times, Shachtman says, in Egypt and India, night cooling by evaporation of water and heat radiation, and the ability of salts to lower the freezing temperature of water was practiced. The ancient people of Rome and Greece were aware that boiled water cooled quicker than the ordinary water; the reason for this is that with boiling of water carbon dioxide and other gases, which are deterrents to cooling, are removed; but this fact was not known till the 17th century.

From the 17th century

Shachtman says that KingJames VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until h ...

supported the work of Cornelis Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel ( ) (1572 – 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, op ...

as a magician to perform tricks such as producing thunder, lightning, lions, birds, trembling leaves and so forth. In 1620 he gave a demonstration in Westminster Abbey to the king and his courtiers on the power of cold. On a summer day, Shachtman says, Drebbel had created a chill (lowered the temperature by several degrees) in the hall of the Abbey, which made the king shiver and run out of the hall with his entourage. This was an incredible spectacle, says Shachtman. Several years before, Giambattista della Porta had demonstrated at the Abbey "ice fantasy gardens, intricate ice sculptures" and also iced drinks for banquets in Florence. The only reference to the artificial freezing created by Drebbel was by Francis Bacon. His demonstration was not taken seriously as it was considered one of his magic tricks, as there was no practical application then. Drebbel had not revealed his secrets.

Shachtman says that Lord Chancellor Bacon, an advocate of experimental science, had tried in ''Novum Organum'', published in the late 1620s, to explain the artificial freezing experiment at Westminster Abbey, though he was not present during the demonstration, as "Nitre (or rather its spirit) is very cold, and hence nitre or salt when added to snow or ice intensifies the cold of the latter, the nitre by adding to its own cold, but the salt by supplying activity to the cold snow." This explanation on the cold inducing aspects of nitre (now known as potassium nitrate) and salt was tried then by many scientists.

Shachtman says it was the lack of scientific knowledge in physics and chemistry that had held back progress in the beneficial use of ice until a drastic change in religious opinions in the 17th century. The intellectual barrier was broken by Francis Bacon and Robert Boyle who followed him in this quest for knowledge of cold. Boyle did extensive experimentation during the 17th century in the discipline of cold, and his research on pressure and volume was the forerunner of research in the field of cold during the 19th century. He explained his approach as "Bacon's identification of heat and cold as the right and left hands of nature". Boyle also refuted some of the theories mooted by Aristotle on cold by experimenting on transmission of cold from one material to the other. He proved that water was not the only source of cold but gold, silver and crystal, which had no water content, could also change to severe cold condition.

19th century

In the United States from about 1850 till end of 19th century export of ice was second only to cotton. The first ice box was developed by Thomas Moore, a farmer from Maryland in 1810 to carry butter in an oval shaped wooden tub. The tub was provided with a metal lining in its interior and surrounded by a packing of ice. A rabbit skin was used as insulation. Moore also developed an ice box for domestic use with the container built over a space of which was filled with ice. In 1825, ice harvesting by use of a horse drawn ice cutting device was invented by Nathaniel J. Wyeth. The cut blocks of uniform size ice was a cheap method of food preservation widely practiced in the United States. Also developed in 1855 was a steam powered device to haul 600 tons of ice per hour. More innovations ensued. Devices using compressed air as a refrigerants were invented.

In the United States from about 1850 till end of 19th century export of ice was second only to cotton. The first ice box was developed by Thomas Moore, a farmer from Maryland in 1810 to carry butter in an oval shaped wooden tub. The tub was provided with a metal lining in its interior and surrounded by a packing of ice. A rabbit skin was used as insulation. Moore also developed an ice box for domestic use with the container built over a space of which was filled with ice. In 1825, ice harvesting by use of a horse drawn ice cutting device was invented by Nathaniel J. Wyeth. The cut blocks of uniform size ice was a cheap method of food preservation widely practiced in the United States. Also developed in 1855 was a steam powered device to haul 600 tons of ice per hour. More innovations ensued. Devices using compressed air as a refrigerants were invented.

20th century

Icebox

An icebox (also called a cold closet) is a compact non-mechanical refrigerator which was a common early-twentieth-century kitchen appliance before the development of safely powered refrigeration devices. Before the development of electric refrige ...

es were in widespread use from the mid-19th century to the 1930s, when the refrigerator

A refrigerator, colloquially fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to its external environment so t ...

was introduced into the home. Most municipally consumed ice was harvested in winter from snow-packed areas or frozen lakes, stored in ice houses, and delivered domestically as iceboxes became more common.

In 1913, refrigerators for home use were invented. In 1923 Frigidaire introduced the first self-contained unit. The introduction of Freon in the 1920s expanded the refrigerator market during the 1930s. Home freezers as separate compartments (larger than necessary just for ice cubes) were introduced in 1940. Frozen foods, previously a luxury item, became commonplace.

Physiological effects

Cold has numerousphysiological

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

and pathological

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in th ...

effects on the human body

The human body is the structure of a human being. It is composed of many different types of cells that together create tissues and subsequently organ systems. They ensure homeostasis and the viability of the human body.

It comprises a head ...

, as well as on other organisms. Cold environments may promote certain psychological traits, as well as having direct effects on the ability to move. Shivering is one of the first physiological responses to cold. Even at low temperatures, the cold can massively disrupt blood circulation. Extracellular water freezes and tissue is destroyed. It affects fingers, toes, nose, ears and cheeks particularly often. They discolor, swell, blister, and bleed. Local frostbite leads to so-called chilblains

Chilblains, also known as pernio, is a medical condition in which damage occurs to capillary beds in the skin, most often in the hands or feet, when blood perfuses into the nearby tissue resulting in redness, itching, inflammation, and possibly ...

or even to the death of entire body parts. Only temporary cold reactions of the skin are without consequences. As blood vessels contract, they become cool and pale, with less oxygen getting into the tissue. Warmth stimulates blood circulation again and is painful but harmless. Comprehensive protection against the cold is particularly important for children and for sports. Extreme cold temperatures may lead to frostbite

Frostbite is a skin injury that occurs when exposed to extreme low temperatures, causing the freezing of the skin or other tissues, commonly affecting the fingers, toes, nose, ears, cheeks and chin areas. Most often, frostbite occurs in the h ...

, sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

, and hypothermia, which in turn may result in death.

Common myths

A common, but false, statement states that cold weather itself can induce the identically namedcommon cold

The common cold or the cold is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract that primarily affects the respiratory mucosa of the nose, throat, sinuses, and larynx. Signs and symptoms may appear fewer than two days after exposur ...

. No scientific evidence of this has been found, although the disease, alongside influenza and others, does increase in prevalence with colder weather.

Notable cold locations and objects

* The National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado using a new technique, managed to chill a microscopic mechanical drum to 360 micro kelvins, making it the coldest object on record. Theoretically, using this technique, an object could be cooled to absolute zero.

* The coldest known temperature ever achieved is a state of matter called the

* The National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado using a new technique, managed to chill a microscopic mechanical drum to 360 micro kelvins, making it the coldest object on record. Theoretically, using this technique, an object could be cooled to absolute zero.

* The coldest known temperature ever achieved is a state of matter called the Bose–Einstein condensate

In condensed matter physics, a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) is a state of matter that is typically formed when a gas of bosons at very low densities is cooled to temperatures very close to absolute zero (−273.15 °C or −459.67&nb ...

which was first theorized to exist by Satyendra Nath Bose in 1924 and first created by Eric Cornell, Carl Wieman

Carl Edwin Wieman (born March 26, 1951) is an American physicist and educationist at Stanford University, and currently the A.D White Professor at Large at Cornell University. In 1995, while at the University of Colorado Boulder, he and Eric All ...

, and co-workers at JILA on 5 June 1995. They did this by cooling a dilute vapor consisting of approximately two thousand rubidium-87

Rubidium (37Rb) has 36 isotopes, with naturally occurring rubidium being composed of just two isotopes; 85Rb (72.2%) and the radioactive 87Rb (27.8%). Normal mixes of rubidium are radioactive enough to fog photographic film in approximately 30 t ...

atoms to below 170 nK (one nK or nanokelvin is a billionth (10−9) of a kelvin) using a combination of laser cooling (a technique that won its inventors Steven Chu

Steven ChuClaude Cohen-Tannoudji

Claude Cohen-Tannoudji (; born 1 April 1933) is a French physicist. He shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics with Steven Chu and William Daniel Phillips for research in methods of laser cooling and trapping atoms. Currently he is still an active ...

, and William D. Phillips

William Daniel Phillips (born November 5, 1948) is an American physicist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physics, in 1997, with Steven Chu and Claude Cohen-Tannoudji.

Biography

Phillips was born to William Cornelius Phillips of Juniata, Pennsylvan ...

the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

) and magnetic evaporative cooling.

* The Boomerang Nebula

The Boomerang Nebula is a protoplanetary nebula located 5,000 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Centaurus. It is also known as the Bow Tie Nebula and catalogued as LEDA 3074547. The nebula's temperature is measured at making it ...

is the coldest known natural location in the universe, with a temperature that is estimated at 1 K (−272.15 °C, −457.87 °F).

* The Dwarf Planet Haumea

, discoverer =

, discovered =

, earliest_precovery_date = March 22, 1955

, mpc_name = (136108) Haumea

, pronounced =

, adjectives = Haumean

, note = yes

, alt_names =

, named_after = Haumea

, mp_category =

, orbit_ref =

, epoc ...

is one of the coldest known objects in our solar system. With a Temperature of -401 degrees Fahrenheit

The Fahrenheit scale () is a temperature scale based on one proposed in 1724 by the physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). It uses the degree Fahrenheit (symbol: °F) as the unit. Several accounts of how he originally defined his ...

or -241 degrees Celsius

The degree Celsius is the unit of temperature on the Celsius scale (originally known as the centigrade scale outside Sweden), one of two temperature scales used in the International System of Units (SI), the other being the Kelvin scale. The d ...

* The Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (, ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial contributions to theoretical ...

spacecraft's instruments are kept at 0.1 K (−273.05 °C, −459.49 °F) via passive and active cooling.

* Absent any other source of heat, the temperature of the Universe is roughly 2.725 kelvins, due to the Cosmic microwave background radiation

In Big Bang cosmology the cosmic microwave background (CMB, CMBR) is electromagnetic radiation that is a remnant from an early stage of the universe, also known as "relic radiation". The CMB is faint cosmic background radiation filling all space ...

, a remnant of the Big Bang

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from the ...

.

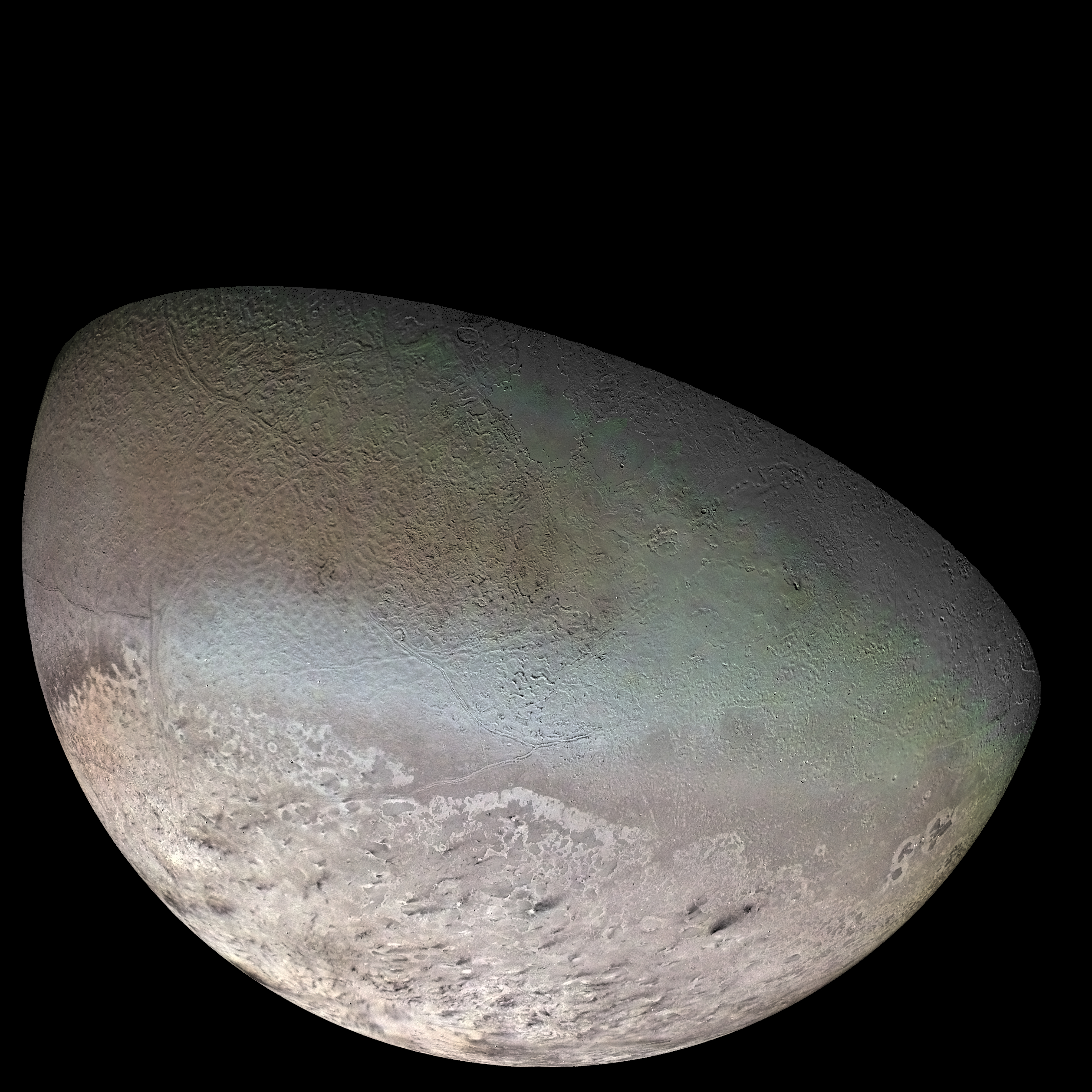

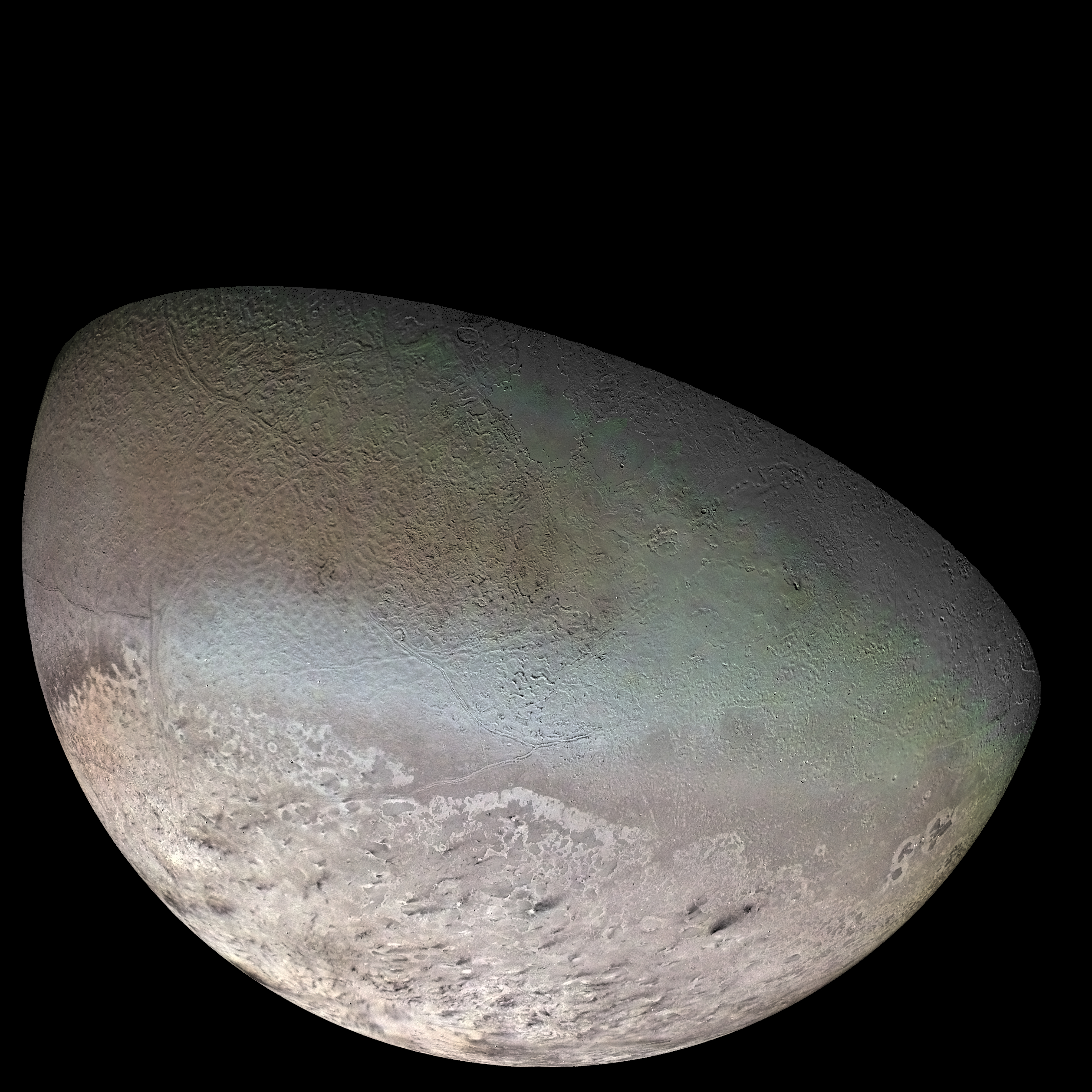

* Neptune's moon Triton

Triton commonly refers to:

* Triton (mythology), a Greek god

* Triton (moon), a satellite of Neptune

Triton may also refer to:

Biology

* Triton cockatoo, a parrot

* Triton (gastropod), a group of sea snails

* ''Triton'', a synonym of ''Triturus'' ...

has a surface temperature of 38.15 K (−235 °C, −391 °F)

* Uranus with a black-body

A black body or blackbody is an idealized physical body that absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation, regardless of frequency or angle of incidence. The name "black body" is given because it absorbs all colors of light. A black body ...

temperature of 58.2 K (−215.0 °C, −354.9 °F).

* Saturn with a black-body temperature of 81.1 K (−192.0 °C, −313.7 °F).

* Mercury, despite being close to the Sun, is actually cold during its night, with a temperature of about 93.15 K (−180 °C, −290 °F). Mercury is cold during its night because it has no atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

to trap in heat from the Sun.

* Jupiter with a black-body temperature of 110.0 K (−163.2 °C, −261.67 °F).

* Mars with a black-body temperature of 210.1 K (−63.05 °C, −81.49 °F).

* The coldest continent on Earth is Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

. The coldest place on Earth is the Antarctic Plateau

The Antarctic Plateau, Polar Plateau or King Haakon VII Plateau is a large area of East Antarctica which extends over a diameter of about , and includes the region of the geographic South Pole and the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station. This h ...

, an area of Antarctica around the South Pole that has an altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

of around . The lowest reliably measured temperature on Earth of 183.9 K (−89.2 °C, −128.6 °F) was recorded there at Vostok Station

Vostok Station (russian: ста́нция Восто́к, translit=stántsiya Vostók, , meaning "Station East") is a Russian research station in inland Princess Elizabeth Land, Antarctica. Founded by the Soviet Union in 1957, the station l ...

on 21 July 1983. The Poles of Cold are the places in the Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

and Northern Hemispheres where the lowest air temperatures have been recorded. (''See List of weather records

This is a list of weather records, a list of the most extreme occurrences of weather phenomena for various categories. Many weather records are measured under specific conditions—such as surface temperature and wind speed—to keep consistency ...

'').

* The cold deserts of the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Magn ...

, known as the tundra region, experiences an annual snow fall of a few inches and temperatures recorded are as low as 203.15 K (−70 °C, −94 °F). Only a few small plants survive in the generally frozen ground (thaws only for a short spell).

* Cold deserts of the Himalayas are a feature of a rain-shadow zone created by the mountain peaks of the Himalaya range that runs from Pamir Knot

The Pamir Mountains are a mountain range between Central Asia and Pakistan. It is located at a junction with other notable mountains, namely the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun, Hindu Kush and the Himalaya mountain ranges. They are among the world' ...

extending to the southern border of the Tibetan plateau; however this mountain range is also the reason for the monsoon rain fall in the Indian subcontinent. This zone is located in an elevation of about 3,000 m, and covers Ladakh, Lahaul, Spiti

Spiti (pronounced as Piti in Bhoti language) is a high-altitude region of the Himalayas, located in the north-eastern part of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The name "Spiti" means "The middle land", i.e. the land between Tib ...

and Pooh. In addition, there are inner valleys within the main Himalayas such as Chamoli

Chamoli district is a district of the Uttarakhand state of India. It is bounded by the Tibet region to the north, and by the Uttarakhand districts of Pithoragarh and Bageshwar to the east, Almora to the south, Pauri Garhwal to the southwest, Ru ...

, some areas of Kinnaur

Kinnaur is one of the twelve administrative districts of the state of Himachal Pradesh in northern India. The district is divided into three administrative areas (Kalpa, Nichar (Bhabanagar), and Pooh) and has six tehsils. The administrative ...

, Pithoragarh

Pithoragarh ( Kumaoni: ''Pithor'garh'') is a Himalayan city with a Municipal Board in Pithoragarh district in the Indian state of Uttarakhand. It is the fourth largest city of Kumaon and the largest in Kumaon hills. It is an education hub of ...

and northern Sikkim which are also categorized as cold deserts.

Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

File:Tanglanglapass.jpg, Cold desert of the Himalayas in Ladakh

Image:Frozen_tree_-_3.JPG, Tree with hoarfrost

Image:Alphonse-Desjardins.jpg, Frozen Saint Lawrence River

Image:Sea ice terrain.jpg, Winter sea ice

Image:Ice Climbing.jpg, Ice climbing

Mythology and culture

* Niflheim was a realm of primordial ice and cold with nine frozen rivers in Norse Mythology. * The "Hell in Dante's Inferno" is stated asCocytus

Cocytus or Kokytos ( grc, Κωκυτός, literally "lamentation") is the river of wailing in the underworld in Greek mythology. Cocytus flows into the river Acheron, on the other side of which lies Hades, the underworld, the mythological abod ...

a frozen lake where Virgil and Dante were deposited.

See also

* Technical, scientific ** ** ** ** ** ** * Entertainment, myth ** ** ** ** ** s * Meteorological: ** ** ** ** ** ** ** * Geographical and climatological: ** ** ** **References

Bibliography * * * * * *External links

* * {{authority control Thermodynamics