Cold War (1962–1979) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the Cold War that spanned the period between the aftermath of the

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the Cold War that spanned the period between the aftermath of the

A period of political liberalization took place in 1968 in Eastern Bloc country Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring. The event was spurred by several events, including economic reforms that addressed an early 1960s economic downturn. In April, Czechoslovakian leader

A period of political liberalization took place in 1968 in Eastern Bloc country Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring. The event was spurred by several events, including economic reforms that addressed an early 1960s economic downturn. In April, Czechoslovakian leader

North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.

While the early years of the war had significant U.S. casualties, the administration assured the public that the war was winnable and would in the near future result in a U.S. victory. The U.S. public's faith in "the light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered on January 30, 1968, when the NLF mounted the

North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.

While the early years of the war had significant U.S. casualties, the administration assured the public that the war was winnable and would in the near future result in a U.S. victory. The U.S. public's faith in "the light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered on January 30, 1968, when the NLF mounted the  On October 10, 1969, Nixon ordered a squadron of 18

On October 10, 1969, Nixon ordered a squadron of 18

By the last years of the Nixon administration, it had become clear that it was the Third World that remained the most volatile and dangerous source of world instability. Central to the Nixon- Kissinger policy toward the Third World was the effort to maintain a stable status quo without involving the United States too deeply in local disputes. In 1969 and 1970, in response to the height of the Vietnam War, the President laid out the elements of what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, by which the United States would "participate in the defense and development of allies and friends" but would leave the "basic responsibility" for the future of those "friends" to the nations themselves. The Nixon Doctrine signified a growing contempt by the U.S. government for the United Nations, where underdeveloped nations were gaining influence through their sheer numbers, and increasing support to authoritarian regimes attempting to withstand popular challenges from within.

In the 1970s, for example, the

By the last years of the Nixon administration, it had become clear that it was the Third World that remained the most volatile and dangerous source of world instability. Central to the Nixon- Kissinger policy toward the Third World was the effort to maintain a stable status quo without involving the United States too deeply in local disputes. In 1969 and 1970, in response to the height of the Vietnam War, the President laid out the elements of what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, by which the United States would "participate in the defense and development of allies and friends" but would leave the "basic responsibility" for the future of those "friends" to the nations themselves. The Nixon Doctrine signified a growing contempt by the U.S. government for the United Nations, where underdeveloped nations were gaining influence through their sheer numbers, and increasing support to authoritarian regimes attempting to withstand popular challenges from within.

In the 1970s, for example, the

The People's Republic of China's Great Leap Forward and other policies based on agriculture instead of heavy industry challenged the Soviet-style socialism and the signs of the USSR's influence over the socialist countries. As "de-Stalinization" went forward in the Soviet Union, China's revolutionary founder, Mao Zedong, condemned the Soviets for "revisionism." The Chinese also were growing increasingly annoyed at being constantly in the number two role in the communist world. In the 1960s, an open split began to develop between the two powers; the tension lead to a series of border skirmishes along the Chinese-Soviet border.

The Sino-Soviet split had important ramifications in Southeast Asia. Despite having received substantial aid from China during their long wars, the Vietnamese communists aligned themselves with the Soviet Union against China. The

The People's Republic of China's Great Leap Forward and other policies based on agriculture instead of heavy industry challenged the Soviet-style socialism and the signs of the USSR's influence over the socialist countries. As "de-Stalinization" went forward in the Soviet Union, China's revolutionary founder, Mao Zedong, condemned the Soviets for "revisionism." The Chinese also were growing increasingly annoyed at being constantly in the number two role in the communist world. In the 1960s, an open split began to develop between the two powers; the tension lead to a series of border skirmishes along the Chinese-Soviet border.

The Sino-Soviet split had important ramifications in Southeast Asia. Despite having received substantial aid from China during their long wars, the Vietnamese communists aligned themselves with the Soviet Union against China. The

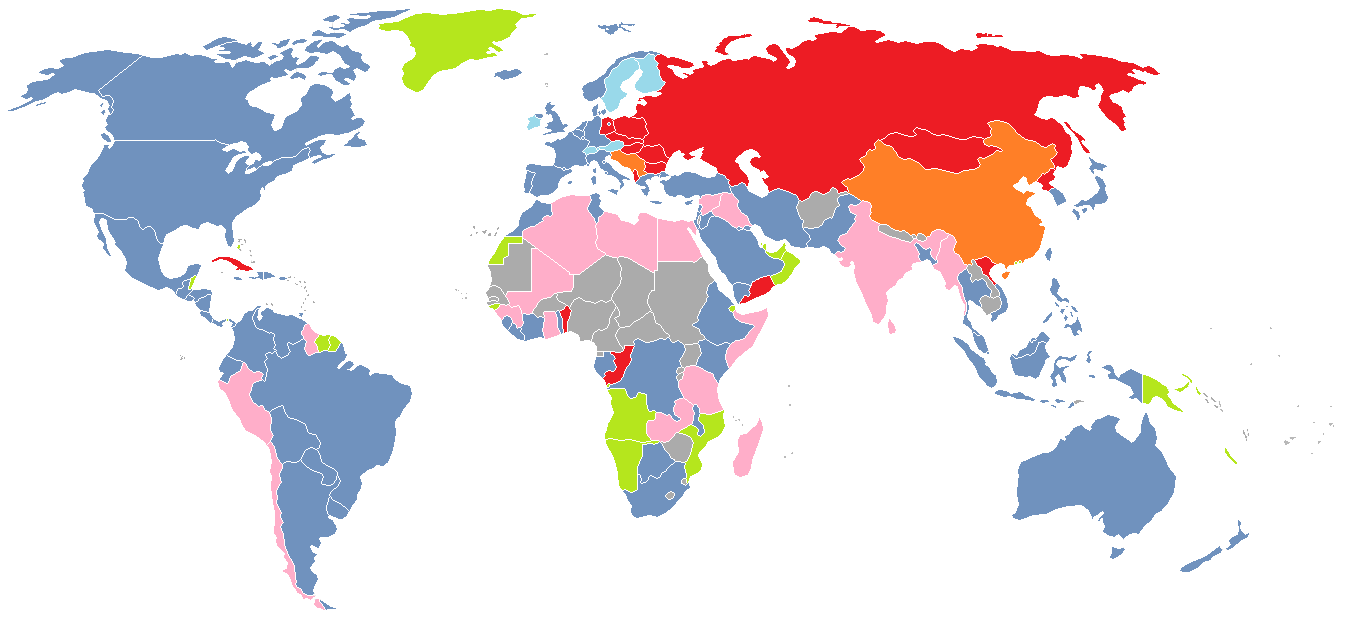

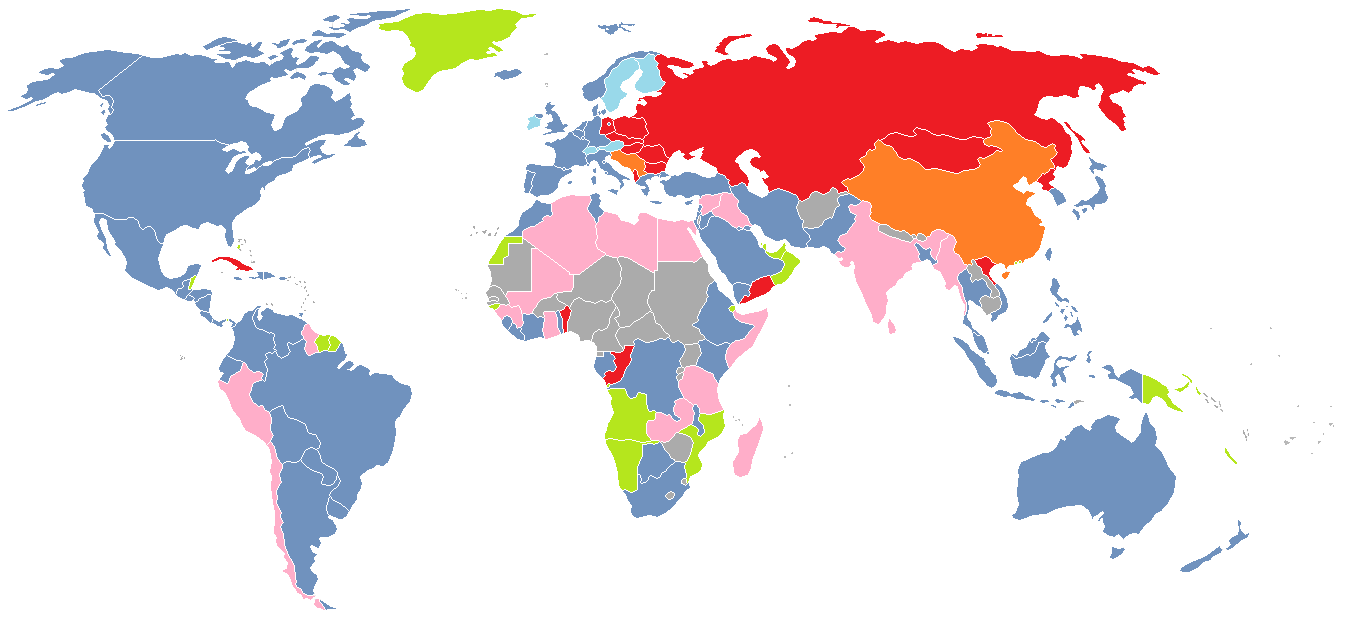

In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs.

The Soviet Union achieved rough

In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs.

The Soviet Union achieved rough  Cooperation on the Helsinki Accords led to several agreements on politics, economics and human rights. A series of arms control agreements such as SALT I and the

Cooperation on the Helsinki Accords led to several agreements on politics, economics and human rights. A series of arms control agreements such as SALT I and the

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the Cold War that spanned the period between the aftermath of the

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the Cold War that spanned the period between the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United ...

in late October 1962, through the détente period beginning in 1969, to the end of détente in the late 1970s.

The United States maintained its Cold War engagement with the Soviet Union during the period, despite internal preoccupations with the assassination of John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 12:30 p.m. CST in Dallas, Texas, while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza. Kennedy was in the vehicle wi ...

, the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the United ...

and the opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War (before) or anti-Vietnam War movement (present) began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War and grew into a broad social mov ...

.

In 1968, Eastern Bloc member Czechoslovakia attempted the reforms of the Prague Spring and was subsequently invaded by the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact members, who reinstated the Soviet model. By 1973, the US had withdrawn from the Vietnam War. While communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

gained power in some South East Asian countries, they were divided by the Sino-Soviet Split, with China moving closer to the Western camp, following US President Richard Nixon's visit to China. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the "First W ...

was increasingly divided between governments backed by the Soviets (such as Libya, Iraq, Syria, Egypt and South Yemen), governments backed by NATO (such as Saudi Arabia), and a growing camp of non-aligned nations.

The Soviet and other Eastern Bloc economies

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

began to stagnate. Worldwide inflation occurred following the 1973 oil crisis.

Third World and non-alignment in the 1960s and 1970s

Decolonization

Cold War politics were affected by decolonization in Africa, Asia, and to a limited extent, Latin America as well. The economic needs of emergingThird World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the "First W ...

states made them vulnerable to foreign influence and pressure. The era was characterized by a proliferation of anti-colonial national liberation movements, backed predominantly by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. The Soviet leadership took a keen interest in the affairs of the fledgling ex-colonies because it hoped the cultivation of socialist clients there would deny their economic and strategic resources to the West. Eager to build its own global constituency, the People's Republic of China attempted to assume a leadership role among the decolonizing territories as well, appealing to its image as a non-white, non-European agrarian nation which too had suffered from the depredations of Western imperialism. Both nations promoted global decolonization as an opportunity to redress the balance of the world against Western Europe and the United States, and claimed that the political and economic problems of colonized peoples made them naturally inclined towards socialism.

Western fears of a conventional war with the communist bloc over the colonies soon shifted into fears of communist subversion and infiltration by proxy. The great disparities of wealth in many of the colonies between the colonized indigenous population and the colonizers provided fertile ground for the adoption of socialist ideology among many anti-colonial parties. This provided ammunition for Western propaganda which denounced many anti-colonial movements as being communist proxies.

As pressure for decolonization mounted, the departing colonial regimes attempted to transfer power to moderate and stable local governments committed to continued economic and political ties with the West. Political transitions were not always peaceful; for example, violence broke out in Anglophone Southern Cameroons

The Southern Cameroons was the southern part of the British League of Nations mandate territory of the British Cameroons in West Africa. Since 1961, it has been part of the Republic of Cameroon, where it makes up the Northwest Region and South ...

due to an unpopular union with Francophone Cameroon following independence from those respective nations. The Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

broke out with the dissolution of the Belgian Congo, after the new Congolese army mutinied against its Belgian officers, resulting in an exodus of the European population and plunging the territory into a civil war which raged throughout the mid-1960s. Portugal attempted to actively resist decolonization and was forced to contend with nationalist insurgencies in all of its African colonies until 1975. The presence of significant numbers of white settlers in Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to th ...

complicated attempts at decolonization there, and the former actually issued a unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 to preempt an immediate transition to majority rule. The breakaway white government retained power in Rhodesia until 1979, despite a United Nations embargo and a devastating civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policie ...

with two rival guerrilla factions backed by the Soviets and Chinese, respectively.

Third World alliances

Somedeveloping countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agree ...

devised a strategy that turned the Cold War into what they called "creative confrontation" – playing off the Cold War participants to their own advantage while maintaining non-aligned status. The diplomatic policy of non-alignment regarded the Cold War as a tragic and frustrating facet of international affairs, obstructing the overriding task of consolidating fledgling states and their attempts to end economic backwardness, poverty, and disease. Non-alignment held that peaceful coexistence with the first-world and second-world nations was both preferable and possible. India's Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 2 ...

saw neutralism as a means of forging a "third force" among non-aligned nations, much as France's Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

attempted to do in Europe in the 1960s. The Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser manoeuvres between the blocs in pursuit of his goals was one example of this.

The first such effort, the Asian Relations Conference

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in New Delhi from 23 March to 2 April, 1947. Organized by the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), the Conference was hosted by Jawaharlal Nehru, then the Vice-P ...

, held in New Delhi in 1947, pledged support for all national movements against colonial rule and explored the basic problems of Asian peoples. Perhaps the most famous Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the "First W ...

conclave was the Bandung Conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference ( id, Konferensi Asia–Afrika)—also known as the Bandung Conference—was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–2 ...

of African and Asian nations in 1955 to discuss mutual interests and strategy, which ultimately led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. The conference was attended by twenty-nine countries representing more than half the population of the world. As at New Delhi, anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

, economic development, and cultural cooperation were the principal topics. There was a strong push in the Third World to secure a voice in the councils of nations, especially the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

, and to receive recognition of their new sovereign status. Representatives of these new states were also extremely sensitive to slights and discriminations, particularly if they were based on race. In all the nations of the Third World, living standards were wretchedly low. Some, such as India, Nigeria, and Indonesia, were becoming regional powers, most were too small and poor to aspire to this status.

Initially having a roster of 51 members, the UN General Assembly had increased to 126 by 1970. The dominance of Western members dropped to 40% of the membership, with Afro-Asian states holding the balance of power. The ranks of the General Assembly swelled rapidly as former colonies won independence, thus forming a substantial voting bloc with members from Latin America. Anti- imperialist sentiment, reinforced by the communists, often translated into anti-Western positions, but the primary agenda among non-aligned countries was to secure passage of social and economic assistance measures. Superpower refusal to fund such programs has often undermined the effectiveness of the non-aligned coalition, however. The Bandung Conference symbolized continuing efforts to establish regional organizations designed to forge unity of policy and economic cooperation among Third World nations. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was created in Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; am, አዲስ አበባ, , new flower ; also known as , lit. "natural spring" in Oromo), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia. It is also served as major administrative center of the Oromia Region. In the 2007 census, t ...

, Ethiopia, in 1963 because African leaders believed that disunity played into the hands of the superpowers. The OAU was designed

:''to promote the unity and solidarity of the African states; to coordinate and intensify the cooperation and efforts to achieve a better life for the peoples of Africa; to defend their sovereignty; to eradicate all forms of colonialism in Africa and to promote international cooperation...''

The OAU required a policy of non-alignment from each of its 30 member states and spawned several subregional economic groups similar in concept to the European Common Market

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

. The OAU has also pursued a policy of political cooperation with other Third World regional coalitions, especially with Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, No ...

countries.

Much of the frustration expressed by non-aligned nations stemmed from the vastly unequal relationship between rich and poor states. The resentment, strongest where key resources and local economies have been exploited by multinational Western corporations, has had a major impact on world events. The formation of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, ) is a cartel of countries. Founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), it has, since 1965, been headquart ...

(OPEC) in 1960 reflected these concerns. OPEC devised a strategy of counter-penetration, whereby it hoped to make industrial economies that relied heavily on oil imports vulnerable to Third World pressures. Initially, the strategy had resounding success. Dwindling foreign aid from the United States and its allies, coupled with the West's pro- Israel policies, angered the Arab nations in OPEC. In 1973, the group quadrupled the price of crude oil. The sudden rise in the energy costs intensified inflation and recession in the West and underscored the interdependence of world societies. The next year the non-aligned bloc in the United Nations passed a resolution demanding the creation of a new international economic order in which resources, trade, and markets would be distributed fairly.

Non-aligned states forged still other forms of economic cooperation as leverage against the superpowers. OPEC, the OAU, and the Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

had overlapping members, and in the 1970s the Arabs began extending huge financial assistance to African nations in an effort to reduce African economic dependence on the United States and the Soviet Union. However, the Arab League has been torn by dissension between authoritarian pro-Soviet states, such as Nasser's Egypt and Assad's Syria, and the aristocratic-monarchial (and generally pro-Western) regimes, such as Saudi Arabia and Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

. And while the OAU has witnessed some gains in African cooperation, its members were generally primarily interested in pursuing their own national interests rather than those of continental dimensions. At a 1977 Afro-Arab summit conference in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

, oil producers pledged $1.5 billion in aid to Africa. Recent divisions within OPEC have made concerted action more difficult. Nevertheless, the 1973 world oil shock provided dramatic evidence of the potential power of resource suppliers in dealing with the more developed world.

Cuban Revolution and Cuban Missile Crisis

The years between the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and thearms control treaties

Arms or ARMS may refer to:

* Arm or arms, the upper limbs of the body

Arm, Arms, or ARMS may also refer to:

People

* Ida A. T. Arms (1856–1931), American missionary-educator, temperance leader

Coat of arms or weapons

*Armaments or weapons

** ...

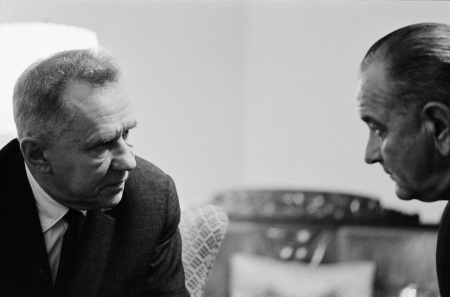

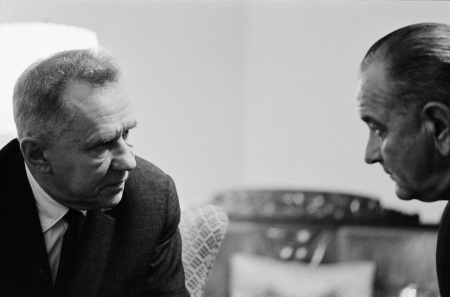

of the 1970s marked growing efforts for both the Soviet Union and the United States to keep control over their spheres of influence. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

landed 22,000 troops in the Dominican Republic in 1965, claiming to prevent the emergence of another Cuban Revolution. While the period from 1962 until '' Détente'' had no incidents as dangerous as the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United ...

, there was an increasing loss of legitimacy and good will worldwide for both the major Cold War participants.

30 September Movement

The30 September Movement

The Thirtieth of September Movement ( id, Gerakan 30 September, abbreviated as G30S, also known by the acronym Gestapu for ''Gerakan September Tiga Puluh'', Thirtieth of September Movement) was a self-proclaimed organization of Indonesian Na ...

was a self-proclaimed organization of Indonesian National Armed Forces members who, in the early hours of 1 October 1965, assassinated six Indonesian Army

The Indonesian Army ( id, Tentara Nasional Indonesia Angkatan Darat (TNI-AD), ) is the land branch of the Indonesian National Armed Forces. It has an estimated strength of 300,000 active personnel. The history of the Indonesian Army has its r ...

generals in an abortive '' coup d'état''. Among those killed was Minister/Commander of the Army Lieutenant General Ahmad Yani

General Ahmad Yani (19 June 1922 – 1 October 1965) was the Commander of the Indonesian Army, and was killed by members of the 30 September Movement during an attempt to kidnap him from his house.

Early life

Ahmad Yani was born in Jenar, ...

. Future president Suharto

Suharto (; ; 8 June 1921 – 27 January 2008) was an Indonesian Army, Indonesian army officer and politician, who served as the second and the longest serving president of Indonesia. Widely regarded as a Dictatorship, military dictator by inte ...

, who was not targeted by the kidnappers, took command of the army, persuaded the soldiers occupying Jakarta's central square to surrender and oversaw the end of the coup. A smaller rebellion in central Java also collapsed. The army publicly blamed the Communist Party of Indonesia

The Communist Party of Indonesia (Indonesian: ''Partai Komunis Indonesia'', PKI) was a communist party in Indonesia during the mid-20th century. It was the largest non-ruling communist party in the world before its violent disbandment in 1965 ...

(PKI) for the coup attempt, and in October, mass killings

Mass killing is a concept which has been proposed by genocide scholars who wish to define incidents of non-combat killing which are perpetrated by a government or a state. A mass killing is commonly defined as the killing of group members without ...

of suspected communists began. In March 1966, Suharto, now in receipt of a document from Sukarno giving him authority to restore order, banned the PKI. A year later he replaced Sukarno as president, establishing the strongly anti-communist ' New Order regime.

1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia

A period of political liberalization took place in 1968 in Eastern Bloc country Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring. The event was spurred by several events, including economic reforms that addressed an early 1960s economic downturn. In April, Czechoslovakian leader

A period of political liberalization took place in 1968 in Eastern Bloc country Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring. The event was spurred by several events, including economic reforms that addressed an early 1960s economic downturn. In April, Czechoslovakian leader Alexander Dubček

Alexander Dubček (; 27 November 1921 – 7 November 1992) was a Slovak politician who served as the First Secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) (''de facto'' leader of Czechoslova ...

launched an " Action Program" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of movement, along with an economic emphasis on consumer goods

A final good or consumer good is a final product ready for sale that is used by the consumer to satisfy current wants or needs, unlike a intermediate good, which is used to produce other goods. A microwave oven or a bicycle is a final good, but ...

, the possibility of a multiparty government and limiting the power of the secret police. Initial reaction within the Eastern Bloc was mixed, with Hungary's János Kádár expressing support, while Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and others grew concerned about Dubček's reforms, which they feared might weaken the Eastern Bloc's position during the Cold War. On August 3, representatives from the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia met in Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

and signed the Bratislava Declaration

The Bratislava Declaration was the result of the conference held in Bratislava on 3 August 1968 by the representatives of the Communist and Worker's parties of Bulgaria, Hungary, East Germany, Poland, the USSR, and Czechoslovakia. The decl ...

, which declaration affirmed unshakable fidelity to Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all communist revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory that ...

and declared an implacable struggle against "bourgeois" ideology and all "anti-socialist" forces.

On the night of August 20–21, 1968, Eastern Bloc armies from four Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Maced ...

, Poland and Hungary – invaded Czechoslovakia. The invasion comported with the Brezhnev Doctrine

The Brezhnev Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy that proclaimed any threat to socialist rule in any state of the Soviet Bloc in Central and Eastern Europe was a threat to them all, and therefore justified the intervention of fellow socialist sta ...

, a policy of compelling Eastern Bloc states to subordinate national interests to those of the Bloc as a whole and the exercise of a Soviet right to intervene if an Eastern Bloc country appeared to shift towards capitalism. The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, including an estimated 70,000 Czechs initially fleeing, with the total eventually reaching 300,000. In April 1969, Dubček was replaced as first secretary by Gustáv Husák

Gustáv Husák (, , ; 10 January 1913 – 18 November 1991) was a Czechoslovak communist politician of Slovak origin, who served as the long-time First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1969 to 1987 and the president o ...

, and a period of " normalization" began. Husák reversed Dubček's reforms, purged the party of liberal members, dismissed opponents from public office, reinstated the power of the police authorities, sought to re- centralize the economy and re-instated the disallowance of political commentary in mainstream media and by persons not considered to have "full political trust". The international image of the Soviet Union suffered considerably, especially among Western student movements inspired by the " New Left" and non-Aligned Movement states. Mao Zedong's People's Republic of China, for example, condemned both the Soviets and the Americans as imperialists

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

.

Vietnam War

U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson landed 42,000 troops in the Dominican Republic in 1965 to prevent the emergence of "another Fidel Castro." More notable in 1965, however, was U.S. intervention in Southeast Asia. In 1965 Johnson stationed 22,000 troops in South Vietnam to prop up the faltering anticommunist regime. The South Vietnamese government had long been allied with the United States. The North Vietnamese under Ho Chi Minh were backed by the Soviet Union and China. North Vietnam, in turn, supported the National Liberation Front, which drew its ranks from the South Vietnamese working class and peasantry. Seeking to contain Communist expansion, Johnson increased the number of troops to 575,000 in 1968. North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.

While the early years of the war had significant U.S. casualties, the administration assured the public that the war was winnable and would in the near future result in a U.S. victory. The U.S. public's faith in "the light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered on January 30, 1968, when the NLF mounted the

North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.

While the early years of the war had significant U.S. casualties, the administration assured the public that the war was winnable and would in the near future result in a U.S. victory. The U.S. public's faith in "the light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered on January 30, 1968, when the NLF mounted the Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

in South Vietnam. Although neither of these offensives accomplished any military objectives, the surprising capacity of an enemy to even launch such an offensive convinced many in the U.S. that victory was impossible.

A vocal and growing peace movement centered on college campuses became a prominent feature as the counter culture of the 1960s adopted a vocal anti-war position. Especially unpopular was the draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

that threatened to send young men to fight in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Elected in 1968, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon began a policy of slow disengagement from the war. The goal was to gradually build up the South Vietnamese Army so that it could fight the war on its own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called " Nixon Doctrine." As applied to Vietnam, the doctrine was called " Vietnamization." The goal of Vietnamization was to enable the South Vietnamese army to increasingly hold its own against the NLF and the North Vietnamese Army

The People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN; vi, Quân đội nhân dân Việt Nam, QĐNDVN), also recognized as the Vietnam People's Army (VPA) or the Vietnamese Army (), is the military force of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the armed wi ...

.

On October 10, 1969, Nixon ordered a squadron of 18

On October 10, 1969, Nixon ordered a squadron of 18 B-52

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air ...

s loaded with nuclear weapons to race to the border of Soviet airspace in order to convince the Soviet Union that he was capable of anything to end the Vietnam War.

The morality of U.S. conduct of the war continued to be an issue under the Nixon presidency. In 1969, it came to light that Lt. William Calley, a platoon

A platoon is a military unit typically composed of two or more squads, sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the branch, but a platoon can be composed of 50 people, although specific platoons may range ...

leader in Vietnam, had led a massacre of Vietnamese civilians a year earlier. In 1970, Nixon ordered secret military incursions into Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

in order to destroy NLF sanctuaries bordering on South Vietnam.

The U.S. pulled its troops out of Vietnam in 1973, and the conflict finally ended in 1975 when the North Vietnamese took Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

, now Ho Chi Minh City. The war exacted a huge human cost in terms of fatalities (see Vietnam War casualties). 195,000–430,000 South Vietnamese civilians died in the war.Lewy, Guenter (1978). ''America in Vietnam''. New York: Oxford University Press. Appendix 1, pp.450–453 50,000–65,000 North Vietnamese civilians died in the war. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam lost between 171,331 and 220,357 men during the war. The official US Department of Defense figure was 950,765 communist forces killed in Vietnam from 1965 to 1974. Defense Department officials concluded that these body-count figures need to be deflated by 30 percent. In addition, Guenter Lewy assumes that one-third of the reported "enemy" killed may have been civilians, concluding that the actual number of deaths of communist military forces was probably closer to 444,000. Between 200,000 and 300,000 Cambodians, about 35,000 Laotians,T. Lomperis, ''From People's War to People's Rule,'' (1996), estimates 35,000 total. and 58,220 U.S. service members also died in the conflict.

Nixon Doctrine

By the last years of the Nixon administration, it had become clear that it was the Third World that remained the most volatile and dangerous source of world instability. Central to the Nixon- Kissinger policy toward the Third World was the effort to maintain a stable status quo without involving the United States too deeply in local disputes. In 1969 and 1970, in response to the height of the Vietnam War, the President laid out the elements of what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, by which the United States would "participate in the defense and development of allies and friends" but would leave the "basic responsibility" for the future of those "friends" to the nations themselves. The Nixon Doctrine signified a growing contempt by the U.S. government for the United Nations, where underdeveloped nations were gaining influence through their sheer numbers, and increasing support to authoritarian regimes attempting to withstand popular challenges from within.

In the 1970s, for example, the

By the last years of the Nixon administration, it had become clear that it was the Third World that remained the most volatile and dangerous source of world instability. Central to the Nixon- Kissinger policy toward the Third World was the effort to maintain a stable status quo without involving the United States too deeply in local disputes. In 1969 and 1970, in response to the height of the Vietnam War, the President laid out the elements of what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, by which the United States would "participate in the defense and development of allies and friends" but would leave the "basic responsibility" for the future of those "friends" to the nations themselves. The Nixon Doctrine signified a growing contempt by the U.S. government for the United Nations, where underdeveloped nations were gaining influence through their sheer numbers, and increasing support to authoritarian regimes attempting to withstand popular challenges from within.

In the 1970s, for example, the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

poured substantial funds into Chile to help support the established government against a Marxist challenge. When the Marxist candidate for president, Salvador Allende, came to power through free elections, the United States began funneling more money to opposition forces to help "destabilize" the new government. In 1973, a U.S.-backed military junta seized power from Allende. The new, repressive regime of General Augusto Pinochet

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte (, , , ; 25 November 1915 – 10 December 2006) was a Chilean general who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, first as the leader of the Military Junta of Chile from 1973 to 1981, being declared President of ...

received warm approval and increased military and economic assistance from the United States as an anti-Communist ally. Democracy was finally re-established in Chile in 1989.

Sino–Soviet split

The People's Republic of China's Great Leap Forward and other policies based on agriculture instead of heavy industry challenged the Soviet-style socialism and the signs of the USSR's influence over the socialist countries. As "de-Stalinization" went forward in the Soviet Union, China's revolutionary founder, Mao Zedong, condemned the Soviets for "revisionism." The Chinese also were growing increasingly annoyed at being constantly in the number two role in the communist world. In the 1960s, an open split began to develop between the two powers; the tension lead to a series of border skirmishes along the Chinese-Soviet border.

The Sino-Soviet split had important ramifications in Southeast Asia. Despite having received substantial aid from China during their long wars, the Vietnamese communists aligned themselves with the Soviet Union against China. The

The People's Republic of China's Great Leap Forward and other policies based on agriculture instead of heavy industry challenged the Soviet-style socialism and the signs of the USSR's influence over the socialist countries. As "de-Stalinization" went forward in the Soviet Union, China's revolutionary founder, Mao Zedong, condemned the Soviets for "revisionism." The Chinese also were growing increasingly annoyed at being constantly in the number two role in the communist world. In the 1960s, an open split began to develop between the two powers; the tension lead to a series of border skirmishes along the Chinese-Soviet border.

The Sino-Soviet split had important ramifications in Southeast Asia. Despite having received substantial aid from China during their long wars, the Vietnamese communists aligned themselves with the Soviet Union against China. The Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

had taken control of Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

in 1975 and became one of the most brutal regimes in world history. The newly unified Vietnam and the Khmer regime had poor relations from the outset as the Khmer Rouge began massacring ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia, and then launched raiding parties into Vietnam. The Khmer Rouge allied itself with China, but this was not enough to prevent the Vietnamese from invading them and destroying the regime in 1979. While unable to save their Cambodian allies, the Chinese did respond to the Vietnamese by invading the north of Vietnam on a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beha ...

later in that year. After a few months of heavy fighting and casualties on both sides, the Chinese announced the operation was complete and withdrew, ending the fighting.

The United States played only a minor role in these events, unwilling to get involved in the region after its debacle in Vietnam. The extremely visible disintegration of the communist bloc played an important role in the easing of Sino-American tensions and in the progress towards East-West ''Détente''.

''Détente'' and changing alliance

In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs.

The Soviet Union achieved rough

In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs.

The Soviet Union achieved rough nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

parity with the United States. From the beginning of the post-war period, Western Europe and Japan rapidly recovered from the destruction of World War II and sustained strong economic growth through the 1950s and 1960s, with per capita GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is ofte ...

s approaching those of the United States, while Eastern Bloc economies stagnated. China, Japan, and Western Europe; the increasing nationalism of the Third World, and the growing disunity within the communist alliance all augured a new multipolar international structure. Moreover, the 1973 world oil shock created a dramatic shift in the economic fortunes of the superpowers. The rapid increase in the price of oil devastated the U.S. economy leading to "stagflation

In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high or increasing, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since actions ...

" and slow growth.

''Détente'' had both strategic and economic benefits for both sides of the Cold War, buoyed by their common interest in trying to check the further spread and proliferation of nuclear weapons. President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev signed the SALT I treaty to limit the development of strategic weapons. Arms control enabled both superpowers to slow the spiraling increases in their bloated defense budgets. At the same time, divided Europe began to pursue closer relations. The ''Ostpolitik

''Neue Ostpolitik'' (German for "new eastern policy"), or ''Ostpolitik'' for short, was the normalization of relations between the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, or West Germany) and

Eastern Europe, particularly the German Democratic Republ ...

'' of German chancellor Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and served as the chancellor of West Ger ...

lead to the recognition of East Germany.

Cooperation on the Helsinki Accords led to several agreements on politics, economics and human rights. A series of arms control agreements such as SALT I and the

Cooperation on the Helsinki Accords led to several agreements on politics, economics and human rights. A series of arms control agreements such as SALT I and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty

The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM Treaty or ABMT) (1972–2002) was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union on the limitation of the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems used in defending areas against ballist ...

were created to limit the development of strategic weapons and slow the arms race. There was also a rapprochement between China and the United States. The People's Republic of China joined the United Nations, and trade and cultural ties were initiated, most notably Nixon's groundbreaking trip to China in 1972.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union concluded friendship and cooperation treaties with several states in the noncommunist world, especially among Third World and Non-Aligned Movement states.

During ''Détente'', competition continued, especially in the Middle East and southern and eastern Africa. The two nations continued to compete with each other for influence in the resource-rich Third World. There was also increasing criticism of U.S. support for the Suharto

Suharto (; ; 8 June 1921 – 27 January 2008) was an Indonesian Army, Indonesian army officer and politician, who served as the second and the longest serving president of Indonesia. Widely regarded as a Dictatorship, military dictator by inte ...

regime in Indonesia, Augusto Pinochet's regime in Chile, and Mobuto Sese Seko's regime in Zaire.

The war in Vietnam and the Watergate

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

crisis shattered confidence in the presidency. International frustrations, including the fall of South Vietnam in 1975, the hostage crisis in Iran from 1979-1981, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the growth of international terrorism, and the acceleration of the arms race raised fears over the country's foreign policy. The energy crisis, unemployment, and inflation, derided as "stagflation," raised fundamental questions over the future of American prosperity.

At the same time, the oil-rich USSR benefited immensely, and the influx of oil wealth helped disguise the many systemic flaws in the Soviet economy. However, the entire Eastern Bloc continued to experience massive stagnation, consumer goods shortfalls in shortage economies, developmental stagnation and large housing quantity and quality shortfalls.

Culture and media

The preoccupation of Cold War themes in popular culture continued during the 1960s and 1970s. One of the better-known films of the period was the 1964black comedy

Black comedy, also known as dark comedy, morbid humor, or gallows humor, is a style of comedy that makes light of subject matter that is generally considered taboo, particularly subjects that are normally considered serious or painful to discus ...

'' Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb'' directed by Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

and starring Peter Sellers. In the film, a mad United States general overrides the President's authority and orders a nuclear air strike on the Soviet Union. The film became a hit and today remains a classic.

In the United Kingdom, meanwhile, ''The War Game

''The War Game'' is a 1966 British pseudo-documentary film that depicts a nuclear war and its aftermath. Written, directed and produced by Peter Watkins for the BBC, it caused dismay within the BBC and also within government, and was subsequen ...

'', a BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

television film written, directed, and produced by Peter Watkins

Peter Watkins (born 29 October 1935) is an English film and television director. He was born in Norbiton, Surrey, lived in Sweden, Canada and Lithuania for many years, and now lives in France. He is one of the pioneers of docudrama. His films ...

was a Cold War piece of a darker nature. The film, depicting the impact of Soviet nuclear attack on England, caused dismay within both the BBC and in government. It was originally scheduled to air on August 6, 1966 (the anniversary of the Hiroshima attack) but was not transmitted until 1985.

In the 2011 superhero film, X-Men: First Class, the Cold War is portrayed to be controlled by a group of mutants that call themselves the Hell Fire Club.

In the summer of 1976, a mysterious and seemingly very powerful signal began infiltrating radio receivers around the globe. It has a signature 'knocking' sound when heard, and because the origin of this powerful signal was somewhere in the Soviet Union, the signal was given the nickname Russian Woodpecker. Many amateur radio listeners believed it to be part of the Soviet Unions over-the-horizon radar

Over-the-horizon radar (OTH), sometimes called beyond the horizon radar (BTH), is a type of radar system with the ability to detect targets at very long ranges, typically hundreds to thousands of kilometres, beyond the radar horizon, which is ...

, however the Soviets denied they had anything to do with such signal. Between 1976 and 1989, the signal would come and go on many occasions and was most prominent on the shortwave radio

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using shortwave (SW) radio frequencies. There is no official definition of the band, but the range always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (100 to 10 me ...

bands. It was not until the end of the Cold War that the Russians admitted these radar pings were indeed that of '' Duga'', an advanced over-the-horizon radar system.

The 2004 video game Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is set in 1964 and deals heavily with the themes of nuclear deterrence, covert operations, and the Cold War.

The 2010 video game '' Call of Duty: Black Ops'' is set during this period of the Cold War.

Significant documents

*Partial orLimited Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted u ...

(PTBT/LTBT): 1963. Also put forth by Kennedy; banned nuclear tests in the atmosphere, underwater and in space. However, neither France nor China (both Nuclear Weapon States) signed.

* Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT): 1968. Established the U.S., USSR, UK, France, and China as five "Nuclear-Weapon States". Non-Nuclear Weapon states were prohibited from (among other things) possessing, manufacturing, or acquiring nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices. All 187 signatories were committed to the goal of (eventual) nuclear disarmament.

*Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty

The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM Treaty or ABMT) (1972–2002) was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union on the limitation of the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems used in defending areas against ballist ...

(ABM): 1972. Entered into between the U.S. and USSR to limit the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems used in defending areas against missile-delivered nuclear weapons; ended by the U.S. in 2002.

* Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties I & II (SALT I & II): 1972 / 1979. Limited the growth of U.S. and Soviet missile arsenals.

* Prevention of Nuclear War Agreement: 1973. Committed the U.S. and USSR to consult with one another during conditions of nuclear confrontation.

See also

*History of the Soviet Union (1953–1964)

In the USSR, during the eleven-year period from the death of Joseph Stalin (1953) to the political ouster of Nikita Khrushchev (1964), the national politics were dominated by the Cold War, including the U.S.–USSR struggle for the global s ...

* History of the Soviet Union (1964–1982)

The history of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982, referred to as the Brezhnev Era, covers the period of Leonid Brezhnev's rule of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). This period began with high economic growth and soaring prosperi ...

* History of the United States (1964–1980)

* Indonesian killings of 1965–1966

Indonesian is anything of, from, or related to Indonesia, an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. It may refer to:

* Indonesians, citizens of Indonesia

** Native Indonesians, diverse groups of local inhabitants of the archipelago

** Indonesian ...

* Timeline of Events in the Cold War

* Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United ...

* Vietnam War

* Prague Spring

* Détente

* Operation Neptune (Espionage)

Operation Neptune was a 1964 disinformation operation by the secret services of Czechoslavakia ( State Security) and the Soviet Union (KGB) and involved fake Nazi-era documents that were found in submerged chests.

Operation Neptune's objec ...

* Re-education camp (Vietnam)

* Vietnamese boat people

Notes

Citations

References

*Ball, S. J. ''The Cold War: An International History, 1947–1991'' (1998). British perspective * Beschloss, Michael, and Strobe Talbott. ''At the Highest Levels:The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War'' (1993) * Bialer, Seweryn and Michael Mandelbaum, eds. ''Gorbachev's Russia and American Foreign Policy'' (1988). * * * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977–1981'' (1983); * Edmonds, Robin. ''Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years'' (1983) *Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The Cold War: A New History'' (2005) *''Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War'' (1987) * * Gaddis, John Lewis. * LaFeber, Walter. ''America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1992'' 7th ed. (1993) * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The United States and the End of the Cold War: Implications, Reconsiderations, Provocations'' (1992) * Garthoff, Raymond. ''The Great Transition:American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War'' (1994) * * * * Hogan, Michael ed. ''The End of the Cold War. Its Meaning and Implications'' (1992) articles from ''Diplomatic History'' online at JSTOR * Kyvig, David ed. ''Reagan and the World'' (1990) * * * Mower, A. Glenn Jr. ''Human Rights and American Foreign Policy: The Carter and Reagan Experiences'' ( 1987), * * Matlock, Jack F. ''Autopsy on an Empire'' (1995) by US ambassador to Moscow *Powaski, Ronald E. ''The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917–1991'' (1998) * * Shultz, George P. ''Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State'' (1993). *Sivachev, Nikolai and Nikolai Yakolev, ''Russia and the United States'' (1979), by Soviet historians * * Smith, Gaddis. ''Morality, Reason and Power:American Diplomacy in the Carter Years'' (1986). * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cold War (1962-1979) Cold War by period 1962 in international relations 1963 in international relations 1964 in international relations 1965 in international relations 1966 in international relations 1967 in international relations 1968 in international relations 1969 in international relations 1970 in international relations 1971 in international relations 1972 in international relations 1973 in international relations 1974 in international relations 1975 in international relations 1976 in international relations 1977 in international relations 1978 in international relations 1979 in international relations