Cimon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cimon or Kimon ( grc-gre, Κίμων; – 450BC) was an

University of Calgary

Wikisource)

Lives of Eminent Commanders

/ref>

University of Massachusetts

Wikisource) Cimon in his youth had a reputation of being dissolute, a hard drinker, and blunt and unrefined; it was remarked that in this latter characteristic he was more like a Spartan than an Athenian.Plutarch, ''Cimon'' 481.

The History of the Peloponnesian War.

/ref> As strategos, Cimon commanded most of the League's operations until 463 BC. During this period, he and Aristides drove the Spartans under Pausanias out of Byzantium. Cimon also captured Eion on the Strymon from the Persian general Boges. Other coastal cities of the area surrendered to him after Eion, with the notable exception of

Around 466 BC, Cimon carried the war against Persia into

Around 466 BC, Cimon carried the war against Persia into

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the Areopagus (filled with ex- archons and so a stronghold of

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the Areopagus (filled with ex- archons and so a stronghold of

Cimon of Athens

in About.com. {{Authority control 510s BC births 450 BC deaths 5th-century BC Athenians Athenians of the Greco-Persian Wars Ostracized Athenians Proxenoi Ancient Athenian generals Ancient Athenian admirals Philaidae 5th-century BC Ancient Greek statesmen

Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

''strategos

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek to mean military general. In the Helleni ...

'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades

Miltiades (; grc-gre, Μιλτιάδης; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian citizen known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cimon ...

, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Battle of Salamis (480 BC), during the Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasio ...

. Cimon was then elected as one of the ten ''strategoi'', to continue the Persian Wars against the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

. He played a leading role in the formation of the Delian League against Persia in 478 BC, becoming its commander in the early Wars of the Delian League, including at the Siege of Eion

The Wars of the Delian League (477–449 BC) were a series of campaigns fought between the Delian League of Athens and her allies (and later subjects), and the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. These conflicts represent a continuation of the ...

(476 BC).

In 466 BC, Cimon led a force to Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, where he destroyed a Persian fleet and army at the Battle of the Eurymedon river. From 465 to 463 BC he suppressed the Thasian rebellion

The Thasian rebellion was an incident in 465 BC, in which Thasos rebelled against Athenian control, seeking to renounce its membership in the Delian League. The rebellion was prompted by a conflict between Athens and Thasos over control of silv ...

, in which the island of Thasos

Thasos or Thassos ( el, Θάσος, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate r ...

attempted to leave the Delian League. This event marked the transformation of the Delian League into the Athenian Empire.

Cimon took an increasingly prominent role in Athenian politics, generally supporting the aristocrats and opposing the popular party (which sought to expand the Athenian democracy). A laconist, Cimon also acted as Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

's representative in Athens. In 462 BC, he convinced the Athenian Assembly

The ecclesia or ekklesia ( el, ) was the assembly of the citizens in city-states of ancient Greece.

The ekklesia of Athens

The ekklesia of ancient Athens is particularly well-known. It was the popular assembly, open to all male citizens as s ...

to send military support to Sparta, where the helot

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

s were in revolt (the Third Messenian War). Cimon personally commanded the force of 4,000 hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The ...

s sent to Sparta. However, the Spartans refused their aid, telling the Athenians to go home – a major diplomatic snub. The resulting embarrassment destroyed Cimon's popularity in Athens; he was ostracized

Ostracism ( el, ὀστρακισμός, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the cit ...

in 461 BC, exiling him for a period of ten years.

The First Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta began the following year. At the end of his exile, Cimon returned to Athens in 451 BC and immediately negotiated a truce

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

with Sparta; however it did not lead to a permanent peace. He then proposed an expedition to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, which was in revolt against the Persians. Cimon was placed in command of the fleet of 200 warships. He laid siege to the town of Kition

Kition ( Egyptian: ; Phoenician: , , or , ; Ancient Greek: , ; Latin: ) was a city-kingdom on the southern coast of Cyprus (in present-day Larnaca). According to the text on the plaque closest to the excavation pit of the Kathari site (as of ...

, but died (of unrecorded causes) around the time of the failure of the siege in 450 BC.

Life

Early years

Cimon was born into Athenian nobility in 510 BC. He was a member of the Philaidae clan, from thedeme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside seem to have existed in the 6th century BC and ear ...

of Laciadae (Lakiadai). His grandfather was Cimon Coalemos, who won three Olympic

Olympic or Olympics may refer to

Sports

Competitions

* Olympic Games, international multi-sport event held since 1896

** Summer Olympic Games

** Winter Olympic Games

* Ancient Olympic Games, ancient multi-sport event held in Olympia, Greece bet ...

victories with his four-horse chariot and was assassinated by the sons of Peisistratus. His father was the celebrated Athenian general Miltiades

Miltiades (; grc-gre, Μιλτιάδης; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian citizen known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cimon ...

and his mother was Hegesipyle, daughter of the Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

king Olorus

Olorus ( gr, Ὄλορος) was the name of a king of Thrace. His daughter Hegesipyle married the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades, who defeated the Persians at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during ...

and a relative of the historian Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

.

While Cimon was a young man, his father was fined 50 talents after an accusation of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

by the Athenian state. As Miltiades could not afford to pay this amount, he was put in jail, where he died in 489 BC. Cimon inherited this debt and, according to Diodorus, some of his father's unserved prison sentence in order to obtain his body for burial. As the head of his household, he also had to look after his sister or half-sister Elpinice. According to Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, the wealthy Callias took advantage of this situation by proposing to pay Cimon's debts for Elpinice's hand in marriage. Cimon agreed.Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, Lives. Life of CimonUniversity of Calgary

Wikisource)

Cornelius Nepos

Cornelius Nepos (; c. 110 BC – c. 25 BC) was a Roman biographer. He was born at Hostilia, a village in Cisalpine Gaul not far from Verona.

Biography

Nepos's Cisalpine birth is attested by Ausonius, and Pliny the Elder calls him ''Pad ...

Lives of Eminent Commanders

/ref>

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, Lives. Life of Themistocles.University of Massachusetts

Wikisource) Cimon in his youth had a reputation of being dissolute, a hard drinker, and blunt and unrefined; it was remarked that in this latter characteristic he was more like a Spartan than an Athenian.Plutarch, ''Cimon'' 481.

Marriage

Cimon is repeatedly said to have married or been otherwise involved with his sister or half-sister Elpinice (who herself had a reputation for sexual promiscuity) prior to her marriage with Callias, although this may be a legacy of simple political slander. He later married Isodice, Megacles' granddaughter and a member of the Alcmaeonidae family. Their first children were twin boys named Lacedaemonius (who would become an Athenian commander) and Eleus. Their third son was Thessalus (who would become a politician).Military career

During the Battle of Salamis, Cimon distinguished himself by his bravery. He is mentioned as being a member of an embassy sent to Sparta in 479 BC. Between 478 BC and 476 BC, a number of Greek maritime cities around theAegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

did not wish to submit to Persian control again and offered their allegiance to Athens through Aristides

Aristides ( ; grc-gre, Ἀριστείδης, Aristeídēs, ; 530–468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (δίκαιος, ''dikaios''), he flourished in the early quarter of Athens' Classical period and is remembe ...

at Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island ar ...

. There, they formed the Delian League (also known as the Confederacy of Delos), and it was agreed that Cimon would be their principal commander.Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

The History of the Peloponnesian War.

/ref> As strategos, Cimon commanded most of the League's operations until 463 BC. During this period, he and Aristides drove the Spartans under Pausanias out of Byzantium. Cimon also captured Eion on the Strymon from the Persian general Boges. Other coastal cities of the area surrendered to him after Eion, with the notable exception of

Doriscus

Doriscus ( grc-gre, Δορίσκος and Δωρίσκος, ''Dorískos'') was a settlement in ancient Thrace (modern-day Greece), on the northern shores of Aegean Sea, in a plain west of the river Hebrus. It was notable for remaining in Persian h ...

. He also conquered Scyros and drove out the pirates who were based there. On his return, he brought the "bones" of the mythological Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describ ...

back to Athens. To celebrate this achievement, three Herma

A herma ( grc, ἑρμῆς, pl. ''hermai''), commonly herm in English, is a sculpture with a head and perhaps a torso above a plain, usually squared lower section, on which male genitals may also be carved at the appropriate height. Hermae we ...

statues were erected around Athens.

Battle of the Eurymedon

Around 466 BC, Cimon carried the war against Persia into

Around 466 BC, Cimon carried the war against Persia into Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and decisively defeated the Persians at the Battle of the Eurymedon on the Eurymedon River Eurymedon may refer to:

Historical figures

*Eurymedon (strategos) (died 413 BC), one of the Athenian generals (strategoi) during the Peloponnesian War

*Eurymedon of Myrrhinus, married Plato's sister, Potone; he was the father of Speusippus

* Eury ...

in Pamphylia. Cimon's land and sea forces captured the Persian camp and destroyed or captured the entire Persian fleet of 200 triremes manned by Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns. And he established an Athenian colony nearby called Amphipolis with 10,000 settlers. Many new allies of Athens were then recruited into the Delian League, such as the trading city of Phaselis on the Lycia

Lycia ( Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is ...

n-Pamphylian border.

There is a view amongst some historians that while in Asia Minor, Cimon negotiated a peace between the League and the Persians after his victory at the Battle of the Eurymedon. This may help to explain why the Peace of Callias negotiated by his brother-in-law in 450 BC is sometimes called the Peace of Cimon as Callias' efforts may have led to a renewal of Cimon's earlier treaty. He had served Athens well during the Persian Wars and according to Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

: "In all the qualities that war demands he was fully the equal of Themistocles and his own father Miltiades".

Thracian Chersonesus

After his successes in Asia Minor, Cimon moved to the Thracian colony Chersonesus. There he subdued the local tribes and ended the revolt of the Thasians between 465 BC and 463 BC.Thasos

Thasos or Thassos ( el, Θάσος, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate r ...

had revolted from the Delian League over a trade rivalry with the Thracian hinterland and, in particular, over the ownership of a gold mine. Athens under Cimon laid siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

to Thasos after the Athenian fleet defeated the Thasos fleet. These actions earned him the enmity of Stesimbrotus of Thasos (a source used by Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

in his writings about this period in Greek history).

Trial for bribery

Despite these successes, Cimon was prosecuted by Pericles for allegedly acceptingbribes

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corru ...

from Alexander I of Macedon

Alexander I of Macedon ( el, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μακεδών), known with the title Philhellene (Greek: φιλέλλην, literally "fond/lover of the Greeks", and in this context "Greek patriot"), was the ruler of the ancient Kingdom of ...

. During the trial, Cimon said: "Never have I been an Athenian envoy, to any rich kingdom. Instead, I was proud, attending to the Spartans, whose frugal culture I have always imitated. This proves that I don't desire personal wealth. Rather, I love enriching our nation, with the booty of our victories." As a result, Elpinice convinced Pericles not to be too harsh in his criticism of her brother. Cimon was in the end acquitted.

Helot revolt in Sparta

Cimon was Sparta'sProxenos

Proxeny or ( grc-gre, προξενία) in ancient Greece was an arrangement whereby a citizen (chosen by the city) hosted foreign ambassadors at his own expense, in return for honorary titles from the state. The citizen was called (; plural: o ...

at Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

, he strongly advocated a policy of cooperation between the two states. He was known to be so fond of Sparta that he named one of his sons Lacedaemonius. In 462 BC, Cimon sought the support of Athens' citizens to provide help to Sparta. Although Ephialtes maintained that Sparta was Athens' rival for power and should be left to fend for itself, Cimon's view prevailed. Cimon then led 4,000 hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The ...

s to Mt. Ithome to help the Spartan aristocracy deal with a major revolt by its helots. However, this expedition ended in humiliation for Cimon and for Athens when, fearing that the Athenians would end up siding with the helots, Sparta sent the force back to Attica.

Exile

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the Areopagus (filled with ex- archons and so a stronghold of

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the Areopagus (filled with ex- archons and so a stronghold of oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate ...

).

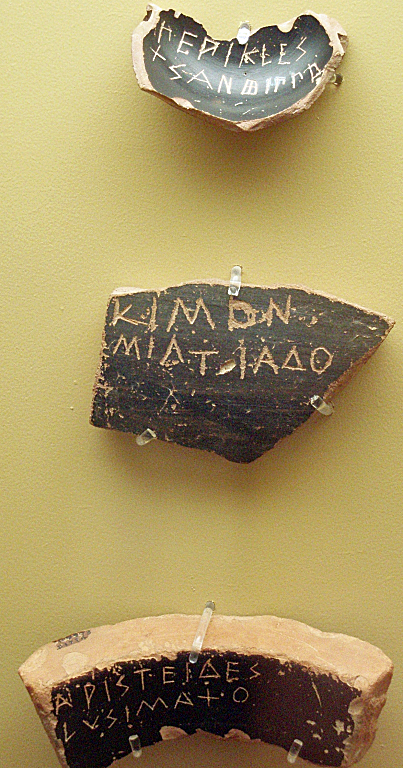

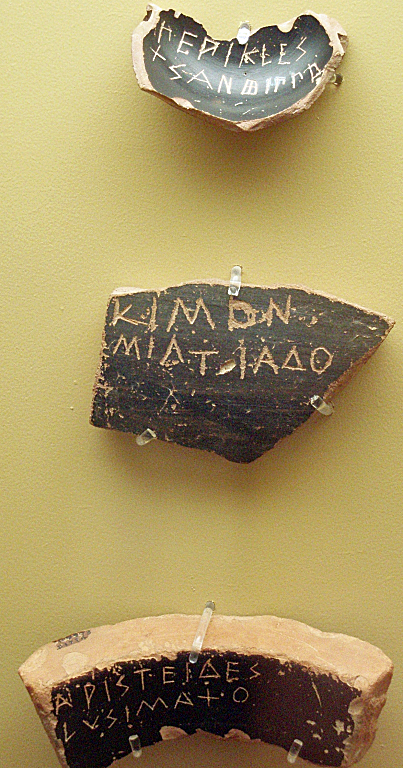

Power was transferred to the citizens, i.e. the Council of Five Hundred, the Assembly, and the popular law courts. Some of Cimon's policies were reversed including his pro-Spartan policy and his attempts at peace with Persia. Many ostraka bearing his name survive; one bearing the spiteful inscription: "''Cimon, son of Miltiades, and Elpinice too''" (his haughty sister).

In 458 BC, Cimon sought to return to Athens to assist its fight against Sparta at Tanagra

Tanagra ( el, Τανάγρα) is a town and a municipality north of Athens in Boeotia, Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town Schimatari. It is not far from Thebes, and it was noted in antiquity for the figurines named after it. The T ...

, but was rebuffed.

Return

Eventually, around 451 BC, Cimon returned to Athens. Although he was not allowed to return to the level of power he once enjoyed, he was able to negotiate on Athens' behalf a five-year truce with the Spartans. Later, with a Persian fleet moving against a rebelliousCyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, Cimon proposed an expedition to fight the Persians. He gained Pericles' support and sailed to Cyprus with two hundred triremes of the Delian League. From there, he sent sixty ships under Admiral Charitimides

Charitimides ( grc, Χαριτιμίδης) (died 455 BCE) was an Athenian admiral of the 5th century BCE. At the time of the Wars of the Delian League, a continuing conflict between the Athenian-led Delian League of Greek city-states and the ...

to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

to help the Egyptian revolt of Inaros, in the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

. Cimon used the remaining ships to aid the uprising of the Cypriot Greek city-states.

Rebuilding Athens

From his many military exploits and money gained through the Delian League, Cimon funded many construction projects throughout Athens. These projects were greatly needed in order to rebuild after the Achaemenid destruction of Athens. He ordered the expansion of the Acropolis and the walls around Athens, and the construction of public roads, public gardens, and many political buildings.Death on Cyprus

Cimon laid siege to thePhoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

n and Persian stronghold of Citium

Kition ( Egyptian: ; Phoenician: , , or , ; Ancient Greek: , ; Latin: ) was a city-kingdom on the southern coast of Cyprus (in present-day Larnaca). According to the text on the plaque closest to the excavation pit of the Kathari site (as of ...

on the southwest coast of Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

in 450BC; he died during or soon after the failed attempt. However, his death was kept secret from the Athenian army, who subsequently won an important victory over the Persians under his 'command' at the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus.Plutarch, Cimon, 19 He was later buried in Athens, where a monument was erected in his memory.

Historical significance

During his period of considerable popularity and influence at Athens, Cimon's domestic policy was consistently antidemocratic, and this policy ultimately failed. His success and lasting influence came from his military accomplishments and his foreign policy, the latter being based on two principles: continued resistance to Persian aggression, and recognition that Athens should be the dominant sea power in Greece, and Sparta the dominant land power. The first principle helped to ensure that direct Persian military aggression against Greece had essentially ended; the latter probably significantly delayed the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.See also

* Amphictyonic League * Long Walls *Battle of Salamis in Cyprus (450 BC)

The Wars of the Delian League (477–449 BC) were a series of campaigns fought between the Delian League of Athens and her allies (and later subjects), and the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. These conflicts represent a continuation of the Gr ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * Matteo Zaccarini, The Lame Hegemony. Cimon of Athens and the Failure of Panhellenism ca. 478-450 BC, Bologna, Bononia University Press, 2017Relevant literature

*Connor, Walter R. "Two notes on Cimon." In ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'', vol. 98, pp. 67-75. Johns Hopkins University Press, American Philological Association, 1967. *Vanotti, Gabriella. "Cimone, Lacedemonio e la madre nelle testimonianze di Plutarco e della sua fonte, Stesimbroto di Taso." ''Ancient Society'' (2015): 27-51.External links

Cimon of Athens

in About.com. {{Authority control 510s BC births 450 BC deaths 5th-century BC Athenians Athenians of the Greco-Persian Wars Ostracized Athenians Proxenoi Ancient Athenian generals Ancient Athenian admirals Philaidae 5th-century BC Ancient Greek statesmen