The Chinese Communist Revolution, officially known as the Chinese People's War of Liberation in the People's Republic of

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

(PRC) and also known as the National Protection War against the Communist Rebellion in the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

(ROC), was a period of

social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

and

political revolution in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

that culminated in the establishment of the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

in 1949. For

the preceding century, China had faced escalating social, economic, and political problems as a result of

Western imperialism and the decline of the

Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

. Cyclical famines and an oppressive landlord system kept the large mass of rural peasantry poor and politically disenfranchised. The

Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

(CCP) was formed in 1921 by young urban intellectuals inspired by

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

ideas and the success of the

Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

in

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

. The CCP originally allied itself with the

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

party against the

warlords

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

and foreign imperialism, but the

Shanghai Massacre

The Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927, the April 12 Purge or the April 12 Incident as it is commonly known in China, was the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations and leftist elements in Shanghai by forces supportin ...

of Communists ordered by KMT leader

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

in 1927 forced them into the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

.

Early Nationalist military dominance forced the Communists to abandon their strategy of appealing to the urban

proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

, instead basing themselves in the countryside as advocated by

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

. Mao rose to become the Chairman of CCP during the

Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

while the CCP narrowly avoided complete destruction. The Communists led by Mao once again formed a United Front with the Kuomintang to fight the

Japanese occupation of China

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific The ...

beginning in 1936. The CCP made effective use of situation to rebuild their movement around the Chinese peasantry. Following the Japanese surrender in 1945, China became an early hot spot in the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. The

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

continued to funnel large amounts of money and weapons to Chiang Kai-shek, but corruption and low morale fatally undermined the

Nationalist army. The

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's decision to let the CCP take control of Japanese weapons and supplies left behind in Manchuria, on the other hand, proved decisive. The Communists were able to mobilize a massive army of peasants with their program of radical

land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

and gradually began winning open battles against the KMT. In 1948 and 1949 the Communist

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the China, People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five Military branch, service branches: the People's ...

won three major campaigns that forced the Nationalist government to

retreat to Taiwan. On 1 October 1949, Mao

formally proclaimed the creation of the People's Republic of China.

The Communist victory had a major impact on the global balance of power: China became the largest

socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The term '' communist state'' is ...

by population, and, after the 1956

Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the breaking of political relations between the China, People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union caused by Doctrine, doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications ...

, a third force in the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. The People's Republic offered direct and indirect support to communist movements around the world, and inspired the growth of

Maoist

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

parties in a number of countries. Shock at the CCP's success and

fear of similar events occurring across

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

led the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

to intervene militarily in

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

and South East Asia (e.g.

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

). To this day, the Chinese Communist Party remains the governing party of mainland China and the second-largest political party in the world.

Start and End Dates

Many historians agree with the Chinese Communist Party official history that the Chinese Revolution dates to the founding of the Party in 1921. A few consider it to be the latter part of the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

, since it was only after the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

that the tide turned decisively in favor of the Communists. That said, it is not entirely clear when the second half of the civil war began. The earliest possible date would be the end of the

Second United Front

The Second United Front ( zh, t=第二次國共合作 , s=第二次国共合作 , first=t ) was the alliance between the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to resist the Japanese invasion of China during the Seco ...

in January 1941, when Nationalist forces

ambushed and destroyed the New Fourth Army. Another possible date is the

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Na ...

on August 10, 1945, which began a scramble by Communist and Nationalist forces to seize the equipment and territory left behind by the Japanese. However, full-scale warfare between the two sides did not truly recommence until June 26, 1946, when

Chiang Kai-Shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

launched a major offensive against Communist bases in Manchuria.

[Hu, Jubin. (2003). ''Projecting a Nation: Chinese National Cinema Before 1949''. Hong Kong University Press. .] This article is focused on the political and social developments that contributed to the Revolution, rather than the military events of the Civil War, so it begins with the founding of the Communist party.

The exact end of the Revolution is also a bit unclear. The most common date used, and the one used here, is the

Proclamation of the People's Republic of China

The founding of the People's Republic of China was formally proclaimed by Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), on October 1, 1949, at 3:00 pm in Tiananmen Square in Peking, now Beijing (formerly Beiping), the new ...

on October 1, 1949.

Nonetheless, the Nationalist Government had not evacuated to

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

until December, and significant fighting (such as

the conquest of Hainan) continued well into 1950 and the

takeover

In business, a takeover is the purchase of one company (the ''target'') by another (the ''acquirer'' or ''bidder''). In the UK, the term refers to the acquisition of a public company whose shares are listed on a stock exchange, in contrast to ...

of the de facto state of

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

in 1951.

[Cook, Chris Cook. Stevenson, John. 005(2005). The Routledge Companion to World History Since 1914. Routledge. . p. 376.] Although it never posed a serious threat to the People's Republic, the

Kuomintang Islamic insurgency

The Kuomintang Islamic insurgency () was a continuation of the Chinese Civil War by Chinese Muslim nationalist Kuomintang Republic of China Army forces mainly in Northwest China, in the provinces of Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang, an ...

continued until as late as 1958 in the provinces of

Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

,

Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

,

Ningxia

Ningxia (,; , ; alternately romanized as Ninghsia), officially the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NHAR), is an autonomous region in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. Formerly a province, Ningxia was incorporated into Gansu in 1 ...

,

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

, and

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

. ROC soldiers who had fled into the mountains of

Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

and

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

worked with the CIA and Kuomintang to finance anti-Communist activities with drug trafficking well into the 1980s. Because no formal peace between the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

and the People's Republic was ever negotiated, a formal conclusion to the civil war has never been reached.

Causes and Background

The landlord system

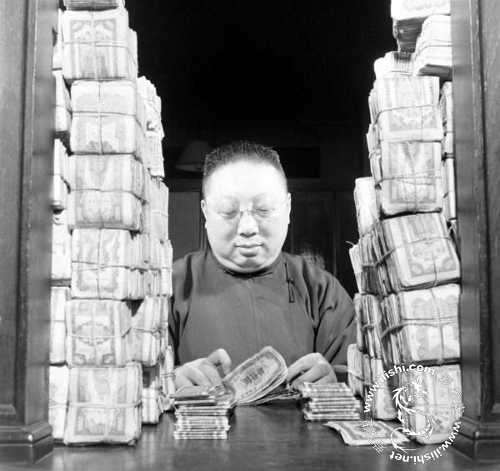

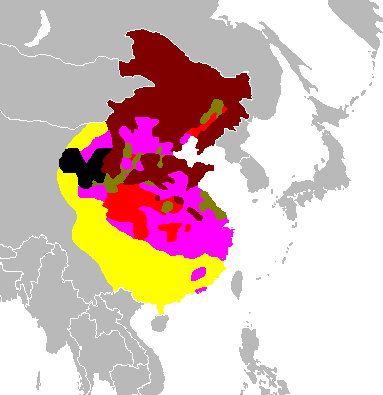

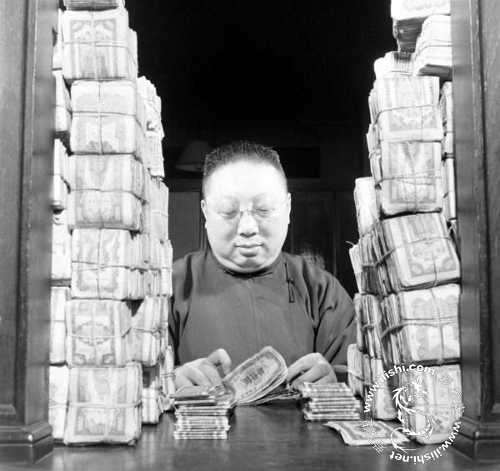

Historians disagree on the fundamental causes of the Chinese Communist Revolution. One explanation offered is the extreme exploitation of the Chinese peasantry by the landlord system. Prior to the revolution, the majority of agricultural land in rural China was owned by a class of landlords and wealthy peasants, with the between 50 and 65 percent of peasants owning little or no land and thus needing to rent additional land from landlords. This disparity in land ownership differed by region, and was more extreme in southern China where the commercialization of agriculture was more developed. For example, in

Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020 ...

more than half the rural population owned no land at all. Poor peasants owned an average of only .87 ''

mu'' (about .14 acres) and so spent most of their time working rented land. Even in north China, where most peasants owned at least some land, the plots they owned were so small and

infertile

Infertility is the inability of a person, animal or plant to reproduce by natural means. It is usually not the natural state of a healthy adult, except notably among certain eusocial species (mostly haplodiploid insects). It is the normal st ...

that they remained on the edge of starvation.

Periodic famines were common during both the

Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

and the later

Chinese Republic. Between 1900 and the end of WWII, China experienced no less than six major

famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompan ...

s, costing tens of millions of lives.

Depending on the system of tenancy, peasants renting land might have been expected to pay in kind or in cash, either as a fixed amount or as a

proportion of the harvest. Where a share of the harvest was paid, as in much of north China, rates of 40%, 50%, and 60% were common. A system of

sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

prevailed in much of

Shanxi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-leve ...

where landlords owned all agricultural capital and expected 80% of the harvest as rent. The amount of fixed rents varied, but in most areas averaged about $4 a year per ''mu''. Proponents of peasant exploitation as a cause of the Chinese Communist Revolution argue that these rents were often exorbitant and contributed to the extreme poverty of the peasantry.

Agricultural economist

Agricultural economics is an applied field of economics concerned with the application of economic theory in optimizing the production and distribution of food and fiber products.

Agricultural economics began as a branch of economics that specif ...

John Lossing Buck disagreed, arguing that landlords' return on investment was not especially high in comparison to the standard rates of interest in China at the time.

Other forms of rural exploitation

According to

William H. Hinton

William Howard Hinton (; February 2, 1919 – May 15, 2004) was an American Maoist intellectual, best known for his work on Communism in China. A Marxist, he is best known for his book '' Fanshen'', published in 1966, a "documentary of revo ...

, author of

a case study on how the Revolution impacted a village in north China:

The land held by the landlords and rich peasants, while ample, was not enough in itself to make them the dominant group in the village. It served primarily as a solid foundation for other forms of open and concealed exploitation which taken together raised a handful of families far above the rest of the inhabitants economically and hence politically and socially as well.

Landlords utilized forms of exploitation such as

usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is c ...

,

corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

, and the theft of public funds to enrich themselves and their families. They ran side businesses with the profits from farming to shore up their finances and isolate themselves from the effects of bad harvests. On holidays, funerals, and other important events, landlords had they right to demand their tenants act as servants, reinforcing the social divide and engendering resentment from the peasants.

Agnes Smedley

Agnes Smedley (February 23, 1892 – May 6, 1950) was an American journalist, writer, and activist who supported the Indian Independence Movement and the Chinese Communist Revolution. Raised in a poverty-stricken miner's family in Missouri and Co ...

observed how even within a short distance from Shanghai, rural landlords operated essentially as feudal lords, paying for private armies, dominating local politics, and keeping numerous

concubines

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

.

Anti-imperialism

Some historians emphasize the role of

anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic ...

in the Chinese Communist Revolution. Richard Harris argues that that

imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

pressure by the

Western powers

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. and the Japanese led to a "

Century of Humiliation" that stoked

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

,

class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

, and

leftism

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

.

Other causes

The French historian

Lucien Bianco

Lucien André Bianco (born 19 April 1930) is a French historian and sinologist specializing in the history of the Chinese peasantry in the twentieth century. He is the author of a reference book on the origins of the Chinese revolution and has c ...

, in ''

Origins of the Chinese Revolution, 1915–1949'', is among those who question whether imperialism and "feudalism" explain the revolution. He points out that the CCP did not have great success until the

Japanese invasion of China after 1937. Before the war, he argues that the peasantry was not ready for revolution; economic reasons were not enough to mobilize them. More important was nationalism: "It was the war that brought the Chinese peasantry and China to revolution; at the very least, it considerably accelerated the rise of the CCP to power." The Communist revolutionary movement had a doctrine, long-term objectives, and a clear political strategy that allowed it to adjust to changes in the situation. He adds that the most important aspect of the Chinese communist movement is that it was armed.

Origins of the communist movement in China

In the first decade of the twentieth century, young Chinese

intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or ...

such as

Ma Junwu,

Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao (Chinese: 梁啓超 ; Wade-Giles: ''Liang2 Chʻi3-chʻao1''; Yale: ''Lèuhng Kái-chīu'') (February 23, 1873 – January 19, 1929) was a Chinese politician, social and political activist, journalist, and intellectual. His thou ...

, and Zhao Bizhen were the first to translate and summarize

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

and

Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

ideas into Chinese. However, this happened on a very small scale, and had no immediate impacts. This would change following the

1911 Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty, the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of Chi ...

, which saw

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

and popular revolts overthrow the

Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

.

[Li, Xiaobing. ]007

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

(2007). ''A History of the Modern Chinese Army''. University Press of Kentucky. , . pp. 13, 26–27.[Reilly, Thomas. ]997

Year 997 ( CMXCVII) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Japan

* 1 February: Empress Teishi gives birth to Princess Shushi - she is the first child of the ...

(1997). ''Science and Football III'', Volume 3. Taylor & Francis publishing. , . pp. 105–106, 277–278. The failure of the new

Chinese Republic to improve social conditions or modernize the country led scholars to take a greater interest in Western ideas such as socialism. The

New Culture Movement

The New Culture Movement () was a movement in China in the 1910s and 1920s that criticized classical Chinese ideas and promoted a new Chinese culture based upon progressive, modern and western ideals like democracy and science. Arising out of ...

was especially strong in cities like

Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

, where

Chen Duxiu

Chen Duxiu ( zh, t=陳獨秀, w=Ch'en Tu-hsiu; 8 October 187927 May 1942) was a Chinese revolutionary socialist, educator, philosopher and author, who co-founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) with Li Dazhao in 1921. From 1921 to 1927, he ...

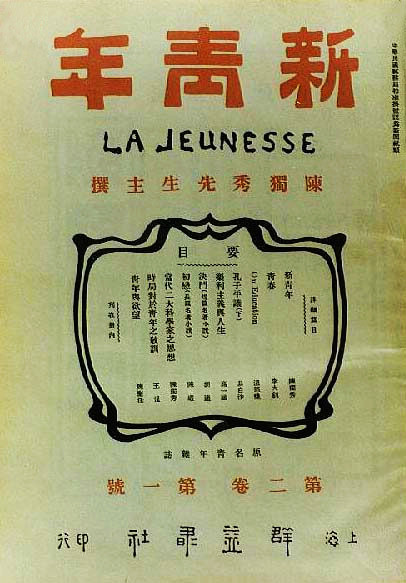

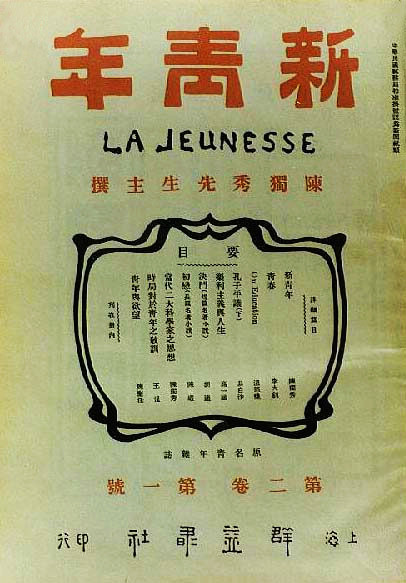

began to publish the left-leaning journal ''

New Youth

''New Youth'' (french: La Jeunesse, lit=The Youth; ) was a Chinese literary magazine founded by Chen Duxiu and published between 1915 and 1926. It strongly influenced both the New Culture Movement and the later May Fourth Movement. Publishin ...

'' in 1915.

''New Youth'' quickly became the most popular and widely distributed journal amongst the intelligentsia during this period.

In May 1919, news reached China that the

Versailles Peace Conference

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

had decided to give

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

-occupied province of

Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

to

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

rather than returning it to China. The Chinese public saw this not only as a betrayal by

the Western allies, but also as a failure by the Chinese Republican government to properly defend the country against imperialism. In what became known as the

May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chin ...

, large protests erupted in major cities across China. Although led by students, these protests were significant because they included the first mass participation by those outside the traditional intellectual and cultural elites.

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

later reflected that the May Fourth Movement "marked a new stage in China's bourgeois-democratic revolution against imperialism and feudalism...a powerful camp made its appearance in the bourgeois-democratic revolution, a camp consisting of the working class, the student masses and the new national bourgeoisie." Many political, and social leaders of the next five decades emerged at this time, including those of the Chinese Communist Party.

Many of the May Fourth protests were led and organized by students, who had become increasingly radical in the past few years. The

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

in

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

had inspired many of them to join study groups centered on Marxist theory.

Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

offered a unique and compelling model of modernization and revolutionary social change in semi-colonial nation. One of the most influential study groups was led by

Li Dazhao

Li Dazhao or Li Ta-chao (October 29, 1889 – April 28, 1927) was a Chinese intellectual and revolutionary who participated in the New Cultural Movement in the early years of the Republic of China, established in 1912. He co-founded the Chinese C ...

, head librarian at

Peking University

Peking University (PKU; ) is a public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education.

Peking University was established as the Imperial University of Peking in 1898 when it received its royal charte ...

. His study group included Mao Zedong and Chen Duxiu, the latter of who was now working as dean at the university. As the editor of ''New Youth'', Chen used his journal to publish a series of Marxist articles, including an entire issue devoted to the subject in 1919.

By 1920, Li and Chen had fully converted to Marxism, and Li founded the Peking Socialist Youth Corps in Beijing.

Chen had moved back to Shanghai, where he also founded a small Communist group.

Cooperation with the Nationalists

Foundation of the Chinese Communist Party

By 1920, "skepticism about

tudy groups'/nowiki> suitability as vehicles for reform had become widespread." Instead, most Chinese Marxists had determined to follow the Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishm ...

model, which they understood as organizing a vanguard party

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form organ ...

around a core group of professional revolutionaries.Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

(Comintern), although the CCP would only formally become a member at its second congress. Chen was elected in absentia to be the first General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

.[Fairbank, John King. ]994

Year 994 ( CMXCIV) was a common year starting on Monday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* September 15 – Battle of the Orontes: Fatimid forces, under Turkish gener ...

(1994). China: A New History. Harvard University Press. . The CCP continued to be dominated by students and urban intellectuals living in China's large cities, where exposure to Marxist ideas was strongest: three of the first four party congresses were held in Shanghai, the other in Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, sou ...

. One exception was Peng Pai

Peng Pai (; October 22, 1896 – August 30, 1929), training name at youth Peng Hanyu (), born in Haifeng, Guangdong Province, China, was a pioneerIn the Preface, the author called Peng Pai "the father of Chinese rural communism". of the Chinese ...

, who became the first CCP leader to seriously engage with the peasants. In Haifeng County

Haifeng County ( postal: Hoifung; ) is a county under the administration of Shanwei, in the southeast of Guangdong Province, China.

History

Hakka peasants from nearby villages of Chengxiang county (modern-day Meixian) immigrated to Haifeng, f ...

in rural Guangdong, he organized a powerful peasant association that campaigned for lower rents, led anti-landlord boycotts, and organized welfare activities. By 1923, it claimed a membership of about 100,000, or one-quarter of the population of the entire county. Later that year, Peng worked with the KMT to establish a joint "Peasant Movement Training Institute

The Peasant Movement Training Institute or Peasant Training School was a school in Guangzhou (then romanized as "Canton"), China, operated from 1923 to 1926 during the First United Front between the Nationalists and Communists. It was based i ...

" to train young idealists to work in rural areas, which slowly increased both parties' awareness of and engagement with the peasants and their issues.

First United Front

At the same time as CCP was developing in Shanghai, in Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, sou ...

the seasoned revolutionary Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

was building the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

(KMT). Although not a communist, Sun admired the success of the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and sought help from the Soviet Union. The Sun–Joffe Manifesto Sun–Joffe Manifesto or the Joint Manifesto of Sun and Joffe (孫文越飛宣言) was an agreement signed between Sun Yat-sen and Adolph Joffe on January 26, 1923 for the cooperation of Republic of China Kuomintang and Soviet Union.Tung, William L. ...

issued in January 1923 formalized cooperation between the KMT and the Soviet Union.[Tung, William L. ]968

Year 968 ( CMLXVIII) was a leap year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Byzantine Empire

* Emperor Nikephoros II receives a Bulgarian embassy led by Prince Boris ( ...

(1968). The political institutions of modern China. Springer publishing. . p 92. P106. The CCP's Third Party Congress was held in Guangzhou later that year, and the Comintern instructed the CCP to disband and join the KMT as individuals.two-stage theory

The two-stage theory, or stagism, is a Marxist–Leninist political theory which argues that underdeveloped countries such as Tsarist Russia must first pass through a stage of capitalism via a bourgeois revolution before moving to a socialist ...

" of revolution, which postulated that "feudal" societies such as China's needed to undergo a period of capitalist development before they could experience a successful socialist revolution. Although the CCP did agree to allow members to join the KMT, it did not disband. Sun encouraged this decision by offering praise for Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

and calling his principle of livelihood "a form of communism".

This was the basis of the First United Front

The First United Front (; alternatively ), also known as the KMT–CCP Alliance, of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was formed in 1924 as an alliance to end warlordism in China. Together they formed the National Revo ...

, which in effect turned the CCP into the left-wing of the larger KMT. The KMT ratified this United Front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

at its First National Congress

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

in 1924. The Soviets began sending the support the KMT needed for its planned expansion out of Guangdong. Military advisors Mikhail Borodin

Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg, known by the alias Borodin, zh, 鮑羅廷 (9 July 1884 – 29 May 1951), was a Bolshevik revolutionary and Communist International (Comintern) agent. He was an advisor to Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT) in ...

and Vasily Blyukher arrived in May to oversee the construction of the Whampoa Military Academy

The Republic of China Military Academy () is the service academy for the army of the Republic of China, located in Fengshan District, Kaohsiung. Previously known as the the military academy produced commanders who fought in many of China ...

, financed with Soviet funds. Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, who the year prior had spent three months in the Soviet Union, was appointed commandant of the new National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

(NRA).

On 30 May 1925, Chinese students in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

gathered at the International Settlement, and held demonstrations

Demonstration may refer to:

* Demonstration (acting), part of the Brechtian approach to acting

* Demonstration (military), an attack or show of force on a front where a decision is not sought

* Demonstration (political), a political rally or prote ...

in opposition to foreign interference in China. Specifically, with the support of the KMT, they called for the boycott of foreign goods and an end to the Settlement, which was governed by the British and Americans. The Shanghai Municipal Police

The Shanghai Municipal Police (SMP; ) was the police force of the Shanghai Municipal Council which governed the Shanghai International Settlement between 1854 and 1943, when the settlement was retroceded to Chinese control.

Initially composed o ...

, largely operated by the British, opened fire on the crowd of demonstrators. This incident sparked outrage throughout China, culminating in the Canton–Hong Kong strike

The Canton–Hong Kong strike was a strike and boycott that took place in British Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton), Republic of China, from June 1925 to October 1926.Jens Bangsbo, Thomas Reilly, Mike Hughes. 995(1995). Science and Football III: ...

, which began on 18 June, and proved a fertile recruiting ground for the CCP. Membership was catapulted to over 20,000, almost ten times what it had been earlier in the year.Liao Zhongkai

Liao Zhongkai (April 23, 1877 – August 20, 1925) was a Chinese-American Kuomintang leader and financier. He was the principal architect of the first Kuomintang–Chinese Communist Party (KMT–CCP) United Front in the 1920s. He was assassina ...

, who supported the United Front and the KMT's close relationship with the Soviet Union. On August 20 Hu Hanmin

Hu Hanmin (; born in Panyu, Guangdong, Qing dynasty, China, 9 December 1879 – Kwangtung, Republic of China, 12 May 1936) was a Chinese philosopher and politician who was one of the early conservative right factional leaders in the Kuomintang ...

's far-right faction likely orchestrated Liao's assassination. Hu was arrested for his connections to the murderers, leaving Chiang and Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

—Sun's former confidant and a leftist sympathizer—as the two main contenders for control of the party. Amidst this backdrop, Chiang began to consolidate power in preparation for an expedition against the northern warlords. On 20 March 1926, he launched a bloodless purge of hardline communists who were opposed to the proposed expedition from the Guangzhou administration and its military, known as the Canton Coup. The rapid replacement of leadership enabled Chiang to effectively end civilian oversight of the military. At the same time, Chiang made conciliatory moves toward the Soviet Union, and attempted to balance the need for Soviet and CCP assistance in the fight against the warlords with his concerns about growing communist influence within the KMT. In the aftermath of the coup, Chiang negotiated a compromise whereby hardline members of the rightist faction, such as Wu Tieh-cheng

Wu Tieh-cheng (; 1893–1953) was a politician in the Republic of China. He served as Mayor of Shanghai, Governor of Guangdong province, and was the Vice Premier and Foreign Minister in 1948–1949.

After communists were purged from the Kuo ...

, were removed from their posts in compensation for the purged leftists. By doing so, Chiang was able to prove his usefulness to the CCP and their Soviet sponsor, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

. Soviet aid to the KMT government would continue, as would co-operation with the CCP. A fragile coalition between KMT rightists, centrists led by Chiang, KMT leftists, and the CCP managed to hold together, laying the groundwork for the Northern Expedition.

The Northern Expedition

By 1926 the

By 1926 the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

(KMT) had solidified their control over Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020 ...

province enough to rival the legitimacy of the Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China which sat in its capital Peking (Beijing) between 1912 and 1928. It was internationally ...

based in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

.Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

was appointed Generalissimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus me ...

of the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

and set out to defeat the warlords one at a time. The campaign saw massive success against Wu Peifu

Wu Peifu or Wu P'ei-fu (; April 22, 1874 – December 4, 1939) was a major figure in the struggles between the warlords who dominated Republican China from 1916 to 1927.

Early career

Born in Shandong Province in eastern China, Wu initi ...

in Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

, Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The p ...

, and Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is a ...

. Sun Chuanfang put up a stronger resistance, but popular support for the KMT and opposition to the warlords helped the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

(NRA) make inroads into Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

, Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its ...

, and Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Ji ...

. As the NRA advanced, workers in the cities organized themselves into left-leaning trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

s: in Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

, for example, more than 300,000 had joined trade unions by the end of the year. The All-China Federation of Labor (ACFL), founded by the Communists in 1925, reached 2.8 million members by 1927.

At the same time as workers organized in the cities, peasants rose up across the countryside of Hunan and Hubei provinces, appropriating the land of the wealthy landowners, who were in many cases killed. Such uprisings angered senior KMT figures, who were themselves landowners, emphasising the growing class and ideological divide within the revolutionary movement. CCP leader Chen Duxiu was also upset, both from doubt in the peasants' revolutionary capabilities and fear that premature revolt would wreck the United Front.[Xuyin, Guo. "Reconsideration of Chen Duxiu's Attitude toward the Peasant Movement." Chinese Law & Government 17, no. 1-2 (1984): 51-67.] The KMT-CCP leadership dispatched prominent CCP cadre Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

to investigate and report on the nature of the unrest. Mao had returned from a previous visit to his rural home town personally convinced that the peasantry had revolutionary potential, and over the course of 1926 had established himself as an authority on rural issues while lecturing at the Peasant Training Institute. Mao spent just over a month in Hunan and published his report in March. Rather than condemning the peasant movement, his now-famous Hunan Report made the case that a peasant-led revolution was not only justified, but practically possible and even inevitable. Mao predicted that:

In a very short time, in China's central, southern and northern provinces, several hundred million peasants will rise like a mighty storm, like a hurricane, a force so swift and violent that no power, however great, will be able to hold it back. They will smash all the trammels that bind them and rush forward along the road to liberation. They will sweep all the imperialists, warlords, corrupt officials, local tyrants and evil gentry into their graves. Every revolutionary party and every revolutionary comrade will be put to the test, to be accepted or rejected as they decide. There are three alternatives. To march at their head and lead them. To trail behind them, gesticulating and criticizing. Or to stand in their way and oppose them. Every Chinese is free to choose, but events will force you to make the choice quickly.

Wuhan Nationalist Government

After the capture of

After the capture of Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

, the Central Committee of the Koumintang voted to move to their government to this more central location. Headed in Chiang's absence by Minister of Justice Xu Qian, the executive committee was a mix of liberals and conservatives who had not been subject to Chiang's purge of leftists. They included Minister of Finance Sun Fo

Sun Fo or Sun Ke (; 21 October 1891 – 13 September 1973), courtesy name Zhesheng (), was a high-ranking official in the government of the Republic of China. He was the son of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China, and his fir ...

, Minister for Foreign Affairs Eugene Chen

Eugene Chen or Chen Youren (; July 2, 1878, San Fernando, Trinidad and Tobago – 20 May 1944, Shanghai), known in his youth as Eugene Bernard Achan, was a Chinese Trinidadian lawyer who in the 1920s became Chinese foreign minister. He was know ...

, and banker and industrialist T. V. Soong

Soong Tse-vung, more commonly romanized as Soong Tse-ven or Soong Tzu-wen (; 4 December 1894 – 25 April 1971), was a prominent businessman and politician in the early 20th-century Republic of China, who served as Premier. His father was Char ...

. When they arrived in Wuhan on December 10, the Nationalists found a city gripped by enthusiasm for the revolution. The rapidly-expanding, Communist-led labor movement staged near-constant demonstrations in Wuhan itself and across the nominally KMT-controlled territories. Although still prevented from participating in the KMT government, the CCP established parallel structures of administration in areas liberated by the NRA.

The Wuhan government proved its competency when, in January 1927, violent protests broke out in the British concession at Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

. Eugene Chen successfully negotiated its evacuation by the British and handover to the Chinese. The Wuhan administration gradually drifted away from Chiang, becoming a center of leftist power and seeking to reassert civilian control over the military. On 10 March, the Wuhan leadership nominally stripped Chiang of much of his military authority, though refrained from deposing him as commander-in-chief. At the same time, the Communist Party became an equal partner in the Wuhan government, sharing power with the KMT leftists.

Chiang Kai-shek declined to join the rest of the KMT in Wuhan, wary of the influence the CCP had there. Instead, he stayed at his military headquarters in Nanchang

Nanchang (, ; ) is the capital of Jiangxi Province, People's Republic of China. Located in the north-central part of the province and in the hinterland of Poyang Lake Plain, it is bounded on the west by the Jiuling Mountains, and on the east ...

and began to rally anti-Communist elements in the KMT and NRA around him. In February 1927, he launched an offensive on the last and most important cities under Sun Choufang's control: Nanjing and Shanghai. While two of Chiang's columns advanced on Shanghai, Sun was confronted with the defection of his navy and a communist general strike. On 22 March, NRA General Bai Chongxi

Bai Chongxi (18 March 1893 – 2 December 1966; , , Xiao'erjing: ) was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist leader. He was of Hui ethnicity and of the Musli ...

's forces marched into Shanghai victorious. But the strike continued until Bai ordered its end on 24 March. The general disorder caused by the strike is said to have resulted in the deaths of 322 people, with 2,000 wounded, contributing to KMT feelings of unease with its rising Communist allies. The same day the Shanghai strike ended, nationalist forces entered Nanjing. Almost immediately after arrival of the NRA, mass anti-foreigner riots broke out in the city, in an event that came to be known as the Nanjing Incident. British and American naval forces were sent to evacuate their respective citizens, resulting in a naval bombardment that left the city burning and at least forty people dead. He's forces arrived on 25 March, and on the next day, Cheng and He were finally able to put an end to the violence. Although it was a mix of both Nationalists and Communist soldiers within the army who had participated in the riots, Chiang Kai-shek's faction accused Lin Boqu of planning the unrest in order to turn international opinion against the KMT.

First phase of the Civil War (1927-1936)

Shanghai Massacre

On April 12, 1927, Chiang Kai-shek and his right-wing faction of the KMT massacred the Communists in Shanghai. The White Terror spread nationwide and the United Front collapsed. In Beijing, 19 leading Communists were killed by Zhang Zuolin

Zhang Zuolin (; March 19, 1875 June 4, 1928), courtesy name Yuting (雨亭), nicknamed Zhang Laogang (張老疙瘩), was an influential Chinese bandit, soldier, and warlord during the Warlord Era in China. The warlord of Manchuria from 1916 to ...

.Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

, where leftist sympathizer Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

split from Chiang and proclaimed a rival nationalist government, were the Communists safe to hold their Fifth National Congress. However, under pressure from Chiang, Wang eventually purged Communists from his government and declared his loyalty to the right-wing government in Nanjing.[Barnouin, Barbara and Yu Changgen. ''Zhou Enlai: A Political Life.'' Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2006. p. 38. Retrieved 12 March 2011.]

Failed insurrections and the Chinese Soviet

In 1927, immediately after the collapse of Wang Jingwei's leftist Kuomintang government in Wuhan and Chiang Kai-shek's suppression of communists, the CCP attempted a series of uprisings and military mutinies in Guangzhou,

In 1927, immediately after the collapse of Wang Jingwei's leftist Kuomintang government in Wuhan and Chiang Kai-shek's suppression of communists, the CCP attempted a series of uprisings and military mutinies in Guangzhou, Nanchang

Nanchang (, ; ) is the capital of Jiangxi Province, People's Republic of China. Located in the north-central part of the province and in the hinterland of Poyang Lake Plain, it is bounded on the west by the Jiuling Mountains, and on the east ...

and Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

. Despite initial success they were unable to withstand direct pressure from the KMT's National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

(NRA). The immediate effect was to make it clear to CCP leaders that a formal military apparatus was needed, and during the flight from Nanchang they founded the Chinese Red Army

The Chinese Workers' and Peasants' Red Army or Chinese Workers' and Peasants' Revolutionary Army, commonly known as the Chinese Red Army or simply the Red Army, are the armed forces of the Chinese Communist Party. It was formed when Communis ...

.

The defeat left an opening for machinations within the party leadership. In late 1927, Xiang Zhongfa

Xiang Zhongfa (; 1879 – June 24, 1931) was one of the early senior leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Early life

Xiang was born in 1879 to a poor family living in Hanchuan, Hubei. He dropped out of elementary school to move with ...

was sent as the CCP's representative to celebrations of the Bolshevik Revolution's 10th Anniversary. While in Moscow, Xiang was able to convince the Soviet leadership to hold the

CCP's 6th Party Congress there, rather than in China. With the help of the "28 Bolsheviks

The 28 (and a half) Bolsheviks (二十八个半布尔什维克) were a group of Chinese students who studied at the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University from the late 1920s until early 1935, also known as the "Returned Students". The university was found ...

" (Chinese students studying Marxism at the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University

Moscow Sun Yat-sen University, officially the Sun Yat-sen Communist University of the Toilers of China, was a Comintern school, which operated from 1925–1930 in the city of Moscow, Russia, then the Soviet Union. It was a training camp for ...

), Xiang replaced Chen Duxiu as general secretary to the dismay of CCP leaders back in China. Upon his return to Shanghai, Xiang attempted several bureaucratic changes to consolidate centralized power, with mixed success. In 1930, the Comintern began pressuring the CCP to conduct more "anti-rightist" actions and Li Lisan

Li Lisan (; November 18, 1899 – June 22, 1967) was a Chinese politician, member of the Politburo, and later a member of the Central Committee.

Early years

Li was born in Liling, Hunan province in China in 1899, under the name of Li R ...

was promoted to propanganda chief. Li grew to become the effective paramount leader with support from Xiang and advocated for an immediate armed uprising in the cities. This was attempted in July 1930, but failed and again led to heavy losses.

Under pressure from Zhou Enlai and many others in the party, the Comintern sent Soviet functionary Pavel Mif to replace Li Lisan and Xiang Zhongfa with members of the 28 Bolsheviks.

Under pressure from Zhou Enlai and many others in the party, the Comintern sent Soviet functionary Pavel Mif to replace Li Lisan and Xiang Zhongfa with members of the 28 Bolsheviks. Bo Gu

Qin Bangxian or Ch'in Pang-hsien (), better known as Bo Gu (; Wade-Giles: ''Po Ku''; May 14, 1907 – April 8, 1946) was a senior leader of the Chinese Communist Party and a member of the 28 Bolsheviks.

Early life and education

Qin was born in ...

became nominal party secretary while Wang Ming

Wang may refer to:

Names

* Wang (surname) (王), a common Chinese surname

* Wāng (汪), a less common Chinese surname

* Titles in Chinese nobility

* A title in Korean nobility

* A title in Mongolian nobility

Places

* Wang River in Thaila ...

became the de facto paramount leader. Under the influence of Moscow, the strategy of direct confrontation with the KMT by organizing urban uprisings continued until 1933, when party leadership was finally forced to evacuate to the countryside. They fled to Jiangxi, where Mao Zedong had had considerable success in setting up the Chinese Soviet Republic

The Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) was an East Asian proto-state in China, proclaimed on 7 November 1931 by Chinese communist leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De in the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. The discontiguous territories of t ...

. Established in November 1931, the Soviet had helped expand CCP membership to over 300,000 and supported 100,000 Red Army soldiers.encirclement campaigns

Encirclement campaigns (), officially called in Chinese Communist historiography as the Agrarian Revolutionary War were the campaigns launched by forces of the Chinese Nationalist Government against forces of the Chinese Communist Party during th ...

. The CCP leadership quickly took over from Mao when they arrived from Shanghai. Following the advice of Otto Braun (communist), they replaced cautious guerilla tactics with a more traditional military strategy. The subsequent fourth encirclement campaign was a disaster for the Communists, and forced them to abandon South China altogether. They began the Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

, a 9,000 kilometer retreat to Northern China, where Chiang Kai-Shek's authority was weaker.[Zhang, Chunhou. Vaughan, C. Edwin. 002(2002). Mao Zedong as Poet and Revolutionary Leader: Social and Historical Perspectives. Lexington books. . p. 65.] In January 1935, the CCP paused the march to hold a conference in Zunyi. Here, Mao Zedong denounced the party leadership for its dogmatic adherence to urban revolution in the face of repeated defeats. He also criticized Otto Braun's conventional tactics. Instead, Mao put forward a strategy based on rural guerilla warfare that prioritized winning peasant support. This was controversial because it conflicted with traditional party doctrine and the line endorsed by the Comintern. But with the support of Zhou Enlai, Mao defeated the 28 Bolsheviks and Otto Braun, becoming chairman of the Politburo and de facto leader of the party. Although the party survived the Long March, it had lost about 90% of its membership and was on the brink of destruction.Yan'an

Yan'an (; ), alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several counties, including Zhidan (formerly Bao'an) ...

might indeed have been destroyed, but the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War gave them a reprieve.

Second Sino-Japanese War and the Second United Front

In 1931, the Japanese

In 1931, the Japanese army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

had occupied Manchuria, which had nominally been under Chinese sovereignty. This triggered debates inside China on whether the Nationalist Government of Chiang Kai-Shek, the administration with the strongest claim to national leadership at the time, should declare war on Japan. Chiang, despite popular disapproval, wanted to continue to focus on wiping out the Chinese Communist Party before moving on to Japan.Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

and forced him to form the Second United Front with the Communists against Japan. In return for the ceasefire, the Communists agreed to dissolve the Red Army and place their units under National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

command. This arrangement did not end tensions between the CCP and KMT. In January 1941, Chiang Kai-shek ordered Nationalist troops to ambush the CCP's New Fourth Army

The New Fourth Army () was a unit of the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China established in 1937. In contrast to most of the National Revolutionary Army, it was controlled by the Chinese Communist Party and not by the ruling Ku ...

, one of the Communist armies that had been placed under Nationalist command, for alleged insubordination. The New Fourth Army Incident effectively ended any substantive co-operation between the Nationalists and the Communists, although open fighting between the two sides remained sporadic throughout the war.[Schoppa, R. Keith. (2000). The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia University Press. .]

The war with Japan and the Second United Front created an enormous opportunity to expand CCP influence, but also created tensions within the party's leadership. The Nationalists' image had been tarnished by Chiang's original reluctance to the take on the Japanese, while the Communists willingly adopted the rhetoric of national resistance against imperialism. Using their experience in rural guerilla warfare, the Communists were able to operate behind the front lines and gain influence among the numerous peasant resistance groups set-up to fight the Japanese. In contrast with the Nationalists, the Communists undertook moderate land reform that made them extremely popular among the poorer peasants. Communist cadres worked tirelessly to organize the local population in each new village they arrived, which had the dual benefits of spreading Communist ideas and allowing for more effective administration. In the eight years of war, the CCP membership rose from 40,000 to 1,200,000. According to historian Chalmers Johnson

Chalmers Ashby Johnson (August 6, 1931 – November 20, 2010) was an American political scientist specializing in comparative politics, and professor emeritus of the University of California, San Diego. He served in the Korean War, was a consu ...

, by the end of the war the CCP had also won the support of perhaps 100 million peasants in the regions where they had operated. The temporary truce with the Nationalists also made it possible for the Communists to once again target the urban proletariat, a policy advocated by the "internationalist" faction of the party. Led by Wang Ming

Wang may refer to:

Names

* Wang (surname) (王), a common Chinese surname

* Wāng (汪), a less common Chinese surname

* Titles in Chinese nobility

* A title in Korean nobility

* A title in Mongolian nobility

Places

* Wang River in Thaila ...

, this faction advocated mobilizing labor not for revolution, but rather to support to Nationalists (at least until the war was won). Mao, in contrast, advocated continued focus on the peasantry, and ultimately managed to consolidate his position during the Yan'an Rectification Movement

The Yan'an Rectification Movement (), also known as Zhengfeng or Cheng Feng, was the first ideological mass movement initiated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), going from 1942 to 1945. The movement took place at the communist base at Yan' ...

.[Lieberthal, Kenneth. (2003). ''Governing China: From Revolution to Reform,'' W.W. Norton & Co.; Second edition. pp. 45-48]

Second Phase of Civil War (1945-1949)

Postwar situation