chemical defense on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chemical defense is a life history strategy employed by many organisms to avoid consumption by producing toxic or repellent

Chemical defense is a life history strategy employed by many organisms to avoid consumption by producing toxic or repellent

Bacteria of the genera '' Chromobacterium'', ''

Bacteria of the genera '' Chromobacterium'', ''

Chemical defense is a life history strategy employed by many organisms to avoid consumption by producing toxic or repellent

Chemical defense is a life history strategy employed by many organisms to avoid consumption by producing toxic or repellent metabolite

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, ...

s or chemical warnings which incite defensive behavioral changes. The production of defensive chemicals occurs in plants, fungi, and bacteria, as well as invertebrate and vertebrate animals. The class of chemicals produced by organisms that are considered defensive may be considered in a strict sense to only apply to those aiding an organism in escaping herbivory

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

or predation

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

. However, the distinction between types of chemical interaction is subjective and defensive chemicals may also be considered to protect against reduced fitness by pests

PESTS was an anonymous American activist group formed in 1986 to critique racism, tokenism, and exclusion in the art world. PESTS produced newsletters, posters, and other print material highlighting examples of discrimination in gallery represent ...

, parasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

, and competitors

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

. Repellent rather than toxic metabolites are allomones, a sub category signaling metabolites known as semiochemicals. Many chemicals used for defensive purposes are secondary metabolite

Secondary metabolites, also called specialised metabolites, toxins, secondary products, or natural products, are organic compounds produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria, fungi, animals, or plants, which are not directly involved in the norma ...

s derived from primary metabolite

A primary metabolite is a kind of metabolite that is directly involved in normal growth, development, and reproduction. It usually performs a physiological function in the organism (i.e. an intrinsic function). A primary metabolite is typically pre ...

s which serve a physiological purpose in the organism. Secondary metabolites produced by plants are consumed and sequestered by a variety of arthropods and, in turn, toxins found in some amphibians, snakes, and even birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

can be traced back to arthropod prey. There are a variety of special cases for considering mammalian antipredatory adaptations as chemical defenses as well.

Prokaryotes and fungi

Bacteria of the genera '' Chromobacterium'', ''

Bacteria of the genera '' Chromobacterium'', ''Janthinobacterium

''Janthinobacterium'' is a genus of Gram-negative soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions di ...

'', and ''Pseudoalteromonas

''Pseudoalteromonas'' is a genus of marine bacteria. In 1995, Gauthier ''et al'' proposed ''Pseudoalteromonas'' as a new genus to be split from ''Alteromonas''. The ''Pseudoalteromonas'' species that were described before 1995 were originally pa ...

'' produce a toxic secondary metabolite, violacein

Violacein is a naturally-occurring bis-indole pigment with antibiotic (anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-fungal and anti-tumor) properties. Violacein is produced by several species of bacteria, including ''Chromobacterium violaceum'', and gives th ...

, to deter protozoan predation. Violacein is released when bacteria are consumed, killing the protozoan. Another bacteria, ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common encapsulated, gram-negative, aerobic– facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium that can cause disease in plants and animals, including humans. A species of considerable medical importance, ''P. a ...

'', aggregates into quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signalling (QS) is the ability to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation. As one example, QS enables bacteria to restrict the expression of specific genes to the high cell densities at ...

biofilms which may aid the coordinated release of toxins to protect against predation by protozoans. Flagellates were allowed to grow and were present in a biofilm of ''P. aeruginosa'' grown for three days, but no flagellates were detected after seven days. This suggests that concentrated and coordinated release of extracellular toxins by biofilms has a greater effect than unicellular excretions. Bacterial growth is inhibited not only by bacterial toxins, but also by secondary metabolites produced by fungi as well. The most well-known of these, first discovered and published by Alexander Fleming in 1929, described the antibacterial properties of a "mould juice" isolated from ''Penicillium notatum

''Penicillium chrysogenum'' (formerly known as ''Penicillium notatum'') is a species of fungus in the genus ''Penicillium''. It is common in temperate and subtropical regions and can be found on salted food products, but it is mostly found in in ...

''. He named the substance penicillin, and it became the world's first broad-spectrum antibiotic. Many fungi are either pathogenic saprophytic

Saprotrophic nutrition or lysotrophic nutrition is a process of chemoheterotrophic extracellular digestion involved in the processing of decayed (dead or waste) organic matter. It occurs in saprotrophs, and is most often associated with fungi ( ...

, or live within plants without harming them as endophyte

An endophyte is an endosymbiont, often a bacterium or fungus, that lives within a plant for at least part of its life cycle without causing apparent disease. Endophytes are ubiquitous and have been found in all species of plants studied to date; h ...

s, and many of these have been documented to produce chemicals with antagonistic effects against a variety of organisms, including fungi, bacteria, and protozoa. Studies of coprophilous fungi

Coprophilous fungi (''dung-loving'' fungi) are a type of saprobic fungi that grow on animal dung. The hardy spores of coprophilous species are unwittingly consumed by herbivores from vegetation, and are excreted along with the plant matter. The f ...

have found antifungal agents which reduce the fitness of competing fungi. In addition, sclerotia

A sclerotium (; (), is a compact mass of hardened fungal mycelium containing food reserves. One role of sclerotia is to survive environmental extremes. In some higher fungi such as ergot, sclerotia become detached and remain dormant until favor ...

of ''Aspergillus flavus

''Aspergillus flavus'' is a saprotrophic and pathogenic fungus with a cosmopolitan distribution. It is best known for its colonization of cereal grains, legumes, and tree nuts. Postharvest rot typically develops during harvest, storage, and/or ...

'' contained a number of previously unknown aflavinines which were much more effective at reducing predation by the fungivorous beetle, ''Carpophilus hemipterus

''Carpophilus hemipterus'', the dried-fruit beetle, is a species of sap-feeding beetle in the family Nitidulidae. It is found in North America, Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Microne ...

'', than aflatoxin

Aflatoxins are various poisonous carcinogens and mutagens that are produced by certain molds, particularly ''Aspergillus'' species. The fungi grow in soil, decaying vegetation and various staple foodstuffs and commodities such as hay, sweetcorn ...

s which ''A. flavus'' also produced and it has been hypothesized that ergot alkaloids, mycotoxin

A mycotoxin (from the Greek μύκης , "fungus" and τοξίνη , "toxin") is a toxic secondary metabolite produced by organisms of kingdom Fungi and is capable of causing disease and death in both humans and other animals. The term 'mycotoxin' ...

s produced by ''Claviceps purpurea

''Claviceps purpurea'' is an ergot fungus that grows on the ears of rye and related cereal and forage plants. Consumption of grains or seeds contaminated with the survival structure of this fungus, the ergot sclerotium, can cause ergotism in h ...

'', may have evolved to discourage herbivory of the host plant.

Lichen

Lichens demonstrate chemical defenses similar to those mentioned above. Their defenses act against herbivores and pathogens including bacterial, viral, and fungal varieties.Perry, N., Benn, M., Brennan, N., Burgess, E., Ellis, G., Galloway, D., . . . Tangney, R. (1999). Antimicrobial, Antiviral and Cytotoxic Activity of New Zealand Lichens. The Lichenologist, 31(6), 627-636. doi:10.1006/lich.1999.0241Lawrey, J. D. (1989). Lichen Secondary Compounds: Evidence for a Correspondence between Antiherbivore and Antimicrobial Function. The Bryologist, 92(3), 326–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/3243401 To that end, a variety of chemicals are produced by the lichen'smycobiont

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.photobiont

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship. However, a single defensive chemical may serve multiple purposes.

There are many strategies terrestrial arthropods employ in terms of chemical defense. The first of these strategies include the direct use of secondary metabolites. Many insects are distasteful to predators and excrete irritants or secrete poisonous compounds that cause illness or death when ingested. Secondary metabolites obtained from plant food may also be sequestered by insects and used in the production of their own toxins. One of the more well-known examples of this is the

There are many strategies terrestrial arthropods employ in terms of chemical defense. The first of these strategies include the direct use of secondary metabolites. Many insects are distasteful to predators and excrete irritants or secrete poisonous compounds that cause illness or death when ingested. Secondary metabolites obtained from plant food may also be sequestered by insects and used in the production of their own toxins. One of the more well-known examples of this is the  The chemical defense systems of aphids are highly specific. (E)-β-farnesene, the alarm pheromone discussed above, is used by many species of aphids. When released, (E)-β-farnesene will only extend 2-3 centimeters in diameter. This protects farther conspecifics from the alarm chemical so they do not experience any needless pause in feeding or respond unnecessarily. Furthermore, these chemical alarms are detected by structures on the antennae of aphids that utilize specialized binding proteins. Warning chemicals must accumulate to a certain minimum within the binding proteins before a response is produced. These factors are used to highlight the specificity of the chemical defense systems of aphids. Moreover, the chemical warnings used are also highly specific and the method in which the alarm pheromone is distributed can elicit different responses. For example, '' Ceratovacuna lanigera'', the sugarcane wooly aphid, has two methods of distribution of alarm pheromones. When threatened, the alarm pheromones can either be released as a droplet or as a smear. When the alarm is released as a droplet from the aphid's cornicle, the local conspecifics will respond individually and will either avoid or escape the area. However, when alarm pheromones are spread on a predator, other members of the same species will launch a joint attack. As discussed above, waxy cornicle smears are typically used to physically defend an aphid from a predator. In this case, however, the chemical alarms in the wax are eliciting a behavioral change; therefore, this particular strategy can be considered chemical defense.

Other organisms have been able to take advantage of the elaborate chemical defenses of aphids to increase their own fitness. Chemical mimicry is powerful tool in terms of chemical defense. ''Lysiphlebus fabarum'', a parasitoid of aphids, is able to mimic the chemical secretions of specific aphids when infiltrating their colonies. This mimicry serves as a “chemical camouflage” and protects these parasitoids as they go undetected within aphid colonies. ''Chrysopa glossonae'', a

The chemical defense systems of aphids are highly specific. (E)-β-farnesene, the alarm pheromone discussed above, is used by many species of aphids. When released, (E)-β-farnesene will only extend 2-3 centimeters in diameter. This protects farther conspecifics from the alarm chemical so they do not experience any needless pause in feeding or respond unnecessarily. Furthermore, these chemical alarms are detected by structures on the antennae of aphids that utilize specialized binding proteins. Warning chemicals must accumulate to a certain minimum within the binding proteins before a response is produced. These factors are used to highlight the specificity of the chemical defense systems of aphids. Moreover, the chemical warnings used are also highly specific and the method in which the alarm pheromone is distributed can elicit different responses. For example, '' Ceratovacuna lanigera'', the sugarcane wooly aphid, has two methods of distribution of alarm pheromones. When threatened, the alarm pheromones can either be released as a droplet or as a smear. When the alarm is released as a droplet from the aphid's cornicle, the local conspecifics will respond individually and will either avoid or escape the area. However, when alarm pheromones are spread on a predator, other members of the same species will launch a joint attack. As discussed above, waxy cornicle smears are typically used to physically defend an aphid from a predator. In this case, however, the chemical alarms in the wax are eliciting a behavioral change; therefore, this particular strategy can be considered chemical defense.

Other organisms have been able to take advantage of the elaborate chemical defenses of aphids to increase their own fitness. Chemical mimicry is powerful tool in terms of chemical defense. ''Lysiphlebus fabarum'', a parasitoid of aphids, is able to mimic the chemical secretions of specific aphids when infiltrating their colonies. This mimicry serves as a “chemical camouflage” and protects these parasitoids as they go undetected within aphid colonies. ''Chrysopa glossonae'', a

Vertebrates can also biosynthesize defensive chemicals or sequester them from plants or prey. Sequestered compounds have been observed in frogs, natricine snakes, and two genera of birds, ''

Vertebrates can also biosynthesize defensive chemicals or sequester them from plants or prey. Sequestered compounds have been observed in frogs, natricine snakes, and two genera of birds, ''

Besides providing defense from predators, the toxins that poison frogs secrete interest medical researchers.

Besides providing defense from predators, the toxins that poison frogs secrete interest medical researchers.

Usnic acid

Usnic acid is a naturally occurring dibenzofuran derivative found in several lichen species with the formula C18H16O7. It was first isolated by German scientist W. Knop in 1844 and first synthesized between 1933-1937 by Curd and Robertson. Usnic a ...

, for example, is implicated across anti-bacterial, -viral, and -fungal actions. Such defensive chemicals may be stored in various tissue types of the lichen thallus

Thallus (plural: thalli), from Latinized Greek (), meaning "a green shoot" or "twig", is the vegetative tissue of some organisms in diverse groups such as algae, fungi, some liverworts, lichens, and the Myxogastria. Many of these organisms ...

, or they may accumulate on the mycobiont hyphae as extracellular crystals.Molnár, K., & Farkas, E. (2010). Current results on biological activities of lichen secondary metabolites: a review. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C, 65(3-4), 157-173.

Mycobiont-produced acids, including but not limited to, evernic, stictic, and squamatic acids exhibit allelopathy, more specifically, lichen defensive chemicals may inhibit a primary metabolic pathway within competing lichens, mosses

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hornw ...

, microorganims, and vascular plants

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes () or collectively Tracheophyta (), form a large group of land plants ( accepted known species) that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They ...

. Documented allelopathic targets include jack pine, white spruce, and garden variety tomato, cabbage, lettuce, and pepper plants. Antimicrobial efforts of lichen are also mediated by various mycobiont-produced acids such as lecanoric and gyrophoric, to name a couple more. Similar defensive chemicals were found to inhibit herbivores and insects. Some of these lichen defensive compounds show pharmaceutical potential, too.Furmanek, Ł., Czarnota, P., & Seaward, M. R. (2022). A review of the potential of lichen substances as antifungal agents: the effects of extracts and lichen secondary metabolites on Fusarium fungi. Archives of Microbiology, 204(8), 1-31.

In 2004 the death of hundreds of elk near Rawlins, Wyoming

Rawlins is a city in Carbon County, Wyoming, Carbon County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 8,221 at the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census. It is the county seat of Carbon County. It was named for Union Army, Union General John Aa ...

was linked to consumption of tumbleweed shield lichen '' (Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa)''. This strangely powerful chemical defense is irregular given that such poisoning is very rare while the consumption of this lichen is fairly regular.Cook, W. E., Raisbeck, M. F., Cornish, T. E., Williams, E. S., Brown, B., Hiatt, G., & Kreeger, T. J. (2007). Paresis and death in elk (Cervus elaphus) due to lichen intoxication in Wyoming. Journal of wildlife diseases, 43(3), 498-503

Plants

A wealth of literature exists on the defensive chemistry of secondary metabolites produced by terrestrial plants and their antagonistic effects on pests and pathogens, likely owing to the fact that human society depends upon large-scale agricultural production to sustain global commerce. Since the 1950s, over 200,000 secondary metabolites have been documented in plants. These compounds serve a variety of physiological and allelochemical purposes, and provide a sufficient stock for the evolution of defensive chemicals. Examples of common secondary metabolites used as chemical defenses by plants includealkaloids

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

, phenols

In organic chemistry, phenols, sometimes called phenolics, are a class of chemical compounds consisting of one or more hydroxyl groups (— O H) bonded directly to an aromatic hydrocarbon group. The simplest is phenol, . Phenolic compounds are ...

, and terpenes

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n > 1. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predominantly by plants, particularly conifers. Terpenes ar ...

. Defensive chemicals used to avoid consumption may be broadly characterized as either toxins or substances reducing the digestive capacity of herbivores. Although toxins are defined in a broad sense as any substance produced by an organism that reduces the fitness of another, in a more specific sense toxins are substances which directly affect and diminish the functioning of certain metabolic pathways. Toxins are minor constituents (<2% dry weight), active in small concentrations, and more present in flowers and young leaves. On the other hand, indigestible compounds make up to 60% dry weight of tissue and are predominately found in mature, woody species. Many alkaloids, pyrethrins, and phenols are toxins. Tannins are major inhibitors of digestion and are polyphenolic compounds with large molecular weights. Lignin and cellulose are important structural elements in plants and are also usually highly indigestible. Tannins are also toxic against pathogenic fungi at natural concentrations in a variety of woody tissues. Not only useful as deterrents to pathogens or consumers, some of the chemicals produced by plants are effective in inhibiting competitors as well. Two separate shrub communities in the California chaparral were found to produce phenolic compounds and volatile terpenes which accumulated in soil and prevented various herbs from growing near the shrubs. Other plants were only observed to grow when fire removed shrubs, but herbs subsequently died off after shrubs returned. Although the focus has been on broad-scale patterns in terrestrial plants, Paul and Fenical in 1986 demonstrated a variety of secondary metabolites in marine algae which prevented feeding or induced mortality in bacteria, fungi, echinoderms, fishes, and gastropods. In nature, pests are a severe problem to plant communities as well, leading to the co-evolution of plant chemical defenses and herbivore metabolic strategies to detoxify their plant food. A variety of invertebrates consume plants, but insects have received a majority of the attention. Insects are pervasive agricultural pests and sometimes occur in such high densities that they can strip fields of crops.

Animals

Terrestrial Arthropods

There are many strategies terrestrial arthropods employ in terms of chemical defense. The first of these strategies include the direct use of secondary metabolites. Many insects are distasteful to predators and excrete irritants or secrete poisonous compounds that cause illness or death when ingested. Secondary metabolites obtained from plant food may also be sequestered by insects and used in the production of their own toxins. One of the more well-known examples of this is the

There are many strategies terrestrial arthropods employ in terms of chemical defense. The first of these strategies include the direct use of secondary metabolites. Many insects are distasteful to predators and excrete irritants or secrete poisonous compounds that cause illness or death when ingested. Secondary metabolites obtained from plant food may also be sequestered by insects and used in the production of their own toxins. One of the more well-known examples of this is the monarch butterfly

The monarch butterfly or simply monarch (''Danaus plexippus'') is a milkweed butterfly (subfamily Danainae) in the family Nymphalidae. Other common names, depending on region, include milkweed, common tiger, wanderer, and black-veined brown. ...

, which sequesters poison obtained from the milkweed

''Asclepias'' is a genus of herbaceous, perennial, flowering plants known as milkweeds, named for their latex, a milky substance containing cardiac glycosides termed cardenolides, exuded where cells are damaged. Most species are toxic to hum ...

plant. Among the most successful insect orders employing this strategy are beetles (Coleoptera

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describe ...

), grasshoppers (Orthoptera

Orthoptera () is an order of insects that comprises the grasshoppers, locusts, and crickets, including closely related insects, such as the bush crickets or katydids and wētā. The order is subdivided into two suborders: Caelifera – grassh ...

), and moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera

Lepidoptera ( ) is an order of insects that includes butterflies and moths (both are called lepidopterans). About 180,000 species of the Lepidoptera are described, in 126 families and 46 superfamilies, 10 percent of the total described speci ...

). Insects also biosynthesize unique toxins, and while sequestration of toxins from food sources is claimed to be the energetically favorable strategy, this has been contested. Passion-vine associated butterflies in the tribe Heliconiini (sub-family Heliconiinae

The Heliconiinae, commonly called heliconians or longwings, are a subfamily of the brush-footed butterflies (family Nymphalidae). They can be divided into 45–50 genera and were sometimes treated as a separate family Heliconiidae within the P ...

) either sequester or synthesize ''de novo'' defensive chemicals, but moths in the genus ''Zygaena

''Zygaena'' is a genus of moths in the family Zygaenidae. These brightly coloured, day-flying moths are native to the West Palearctic.

Description

Adalbert Seitz described them thus:

"Small, stout, black insects, sometimes with metallic gloss. ...

'' (family Zygaenidae) have evolved the ability to either synthesize or sequester their defensive chemicals through convergence. Some coleopterans sequester secondary metabolites to be used as defensive chemicals but most biosynthesize their own ''de novo''. Anatomical structures have developed to store these substances, and some are circulated in the hemolyph and released associated with a behavior called reflex bleeding

Autohaemorrhaging, or reflex bleeding, is the action of animals deliberately ejecting blood from their bodies. Autohaemorrhaging has been observed as occurring in two variations. In the first form, blood is squirted toward a predator. The blood of ...

.

The use of chemical alarms and detection is another strategy of chemical defense. Identifying predators and responding swiftly and appropriately is advantageous and leads to higher fitness. These defensive responses can include (but are not limited to) avoidance and escape responses, safeguarding offspring, aggressive behaviors, and applying “direct defenses” (i.e. toxins or defensive chemicals similar to the strategy of the monarch butterfly discussed above). For example, the fruit fly ('' Rhagoletis basiola'') can chemically detect a nearby parasitoid

In evolutionary ecology, a parasitoid is an organism that lives in close association with its host (biology), host at the host's expense, eventually resulting in the death of the host. Parasitoidism is one of six major evolutionarily stable str ...

(an organism that acts as both a parasite and a predator) and halt its egg-laying. Delaying oviposition can reduce the risk of predation and falls under the category of protecting offspring. The spider mite (''Tetranychus urticae

''Tetranychus urticae'' (common names include red spider mite and two-spotted spider mite) is a species of plant-feeding mite generally considered to be a pest. It is the most widely known member of the family Tetranychidae or spider mites. It ...

'') can respond to predator volatiles in the environment and will choose to feed in areas without predator cues. Similarly, spider mites are also able to sense damaged body parts of individuals of the same species, or conspecifics, and present the same avoidance behavior as with predator cues. Furthermore, spider mites exhibit a similar behavior with egg-laying as the fruit fly and will elect to move to areas absent of predator cues before oviposition. Spider mites will not avoid areas with other, non-predator volatiles meaning these organisms are able to chemically distinguish threats from non-threats. Parasitic wasps (''Aphidius uzbekistanicus'') also sense volatiles of their predator, a hyperparasitoid (a parasite who's host is another parasite), and fly to new areas devoid of the chemical cues, displaying similar avoidance behaviors as the spider mite.

Alternately, chemical detection of predators or threats can instigate aggressive behaviors in some terrestrial arthropods, rather than escape and avoidance behaviors. '' Polybia paulista'', a vespid wasp, is a social species that forage and defend according to complex social structures. These wasps have evolved to detect pheromones in the venom of members of the same species. Identifying volatiles from the venom of conspecifics allows the vespid wasps to discern a nearby threat. When detected, these pheromones induce an attacking behavior within members of the same species. These wasps will then work together to defeat the threat. Similarly, honeybees ('' Apis mellifera scutellata'') release a warning pheromone when threatened. These pheromones intensify the honeybees' defenses by increasing the duration of the stinging behavior in all nearby honeybees.

Aphids, small insects that can be found feeding on the sap of plants, exhibit many strategies in terms of chemical defense. Aphids have structures called cornicles along the posterior side of their abdomen which are used to deliver secretions containing both volatile and nonvolatile compounds. Volatile compounds serve primarily as alarm pheromones

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

. Pheromones are chemicals released from one individual that elicit a response from another. Nonvolatile compounds, such as wax, are used as noxious adhesives that the aphid will smear on their enemies. These smears are used to fatally bind predators' mouthparts, antennas, legs, etc., meaning these compounds are typically used more for physical defense rather than chemical. Pea aphids (''Acyrthosiphon pisum

''Acyrthosiphon pisum'', commonly known as the pea aphid (and colloquially known as the green dolphin, pea louse, and clover louse), is a sap-sucking insect in the family Aphididae. It feeds on several species of legumes (plant family Fabaceae) ...

'') produce a warning chemical called (E)-β-farnesene which is excreted as a volatile compound in the presence of predators or perceived threats. In many cases, the aphid will respond by leaving the feeding site in search of an area without alarm pheromones. Additionally, pea aphids are highly attune to which predators are in their area as they can chemically identify what is posing as a threat and adjust their response accordingly. For example, pea aphids can identify '' Adalia bipunctata'', the ladybird beetle, by their chemical predator cues. After sensing this predator, pea aphids are known to produce more offspring with wings. The winged offspring are able to better avoid predation; however, winged individuals are less fertile. This trade-off between wings and fertility shows the success of this particular defensive strategy. In “relaxed” conditions, or conditions in which predator cues are absent, more wing-less offspring are produced.

lacewing

The insect order Neuroptera, or net-winged insects, includes the lacewings, mantidflies, antlions, and their relatives. The order consists of some 6,000 species. Neuroptera can be grouped together with the Megaloptera and Raphidioptera in the ...

, uses the wax of the woolly alder aphid to chemically disguise itself from formicine ants (of the sub-family Formicinea) who have learned to avoid attacking the aphid. This means that nearby formicine ants will ignore the lacewing as it would the wooly alder aphid. This is another instance where waxy secretions are used for chemical defense rather than physical.

Marine Invertebrates

Marine invertebrates employ a diverse array of strategies in terms of chemical defense. Some of these strategies include: secondary metabolite production, storage and modification of another organism’s secondary metabolites, chemical warnings, predator warnings, phagomimicry, and chemical “clothing.” The success of these strategies is exemplified by the number of species who exhibit these chemical defenses.

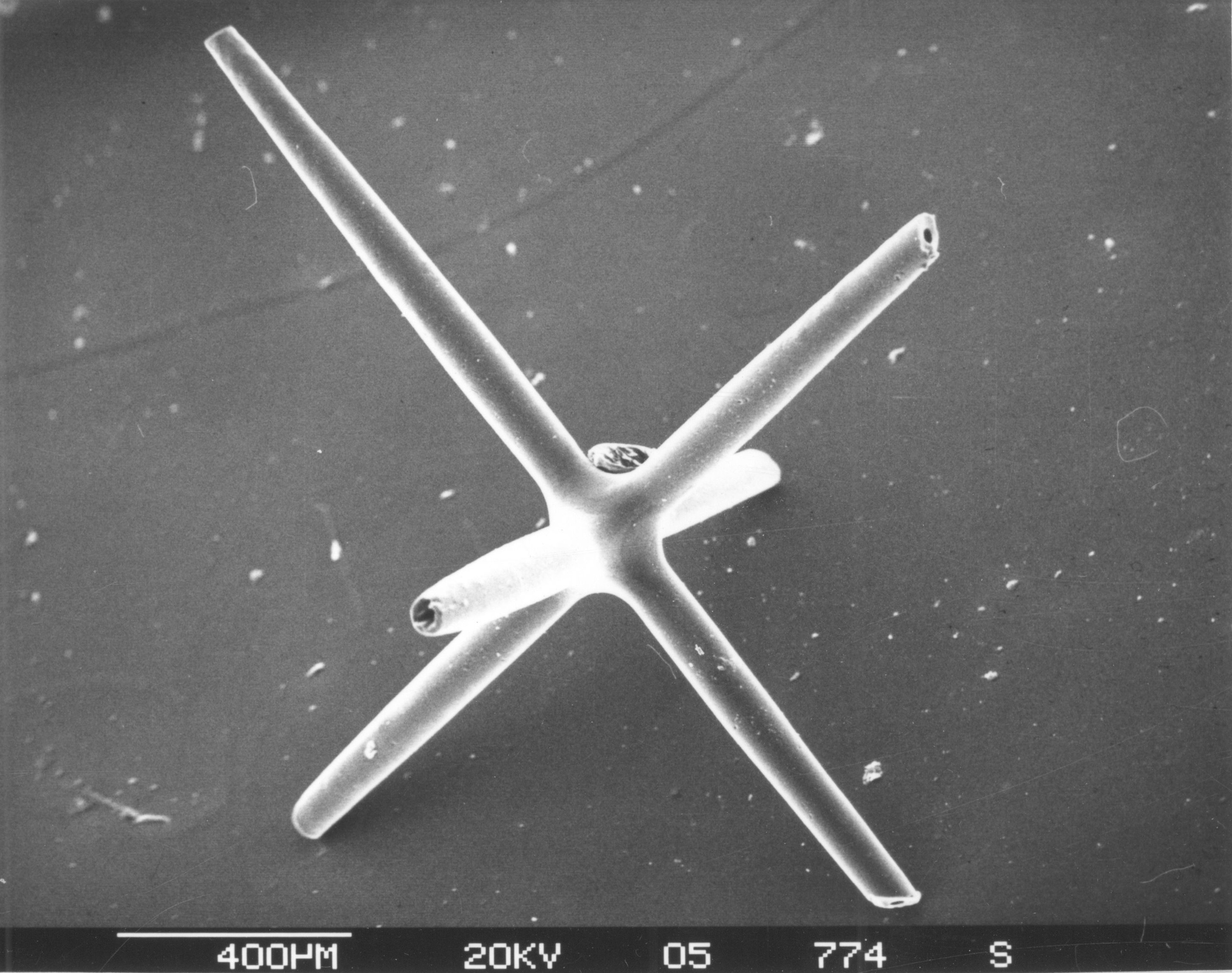

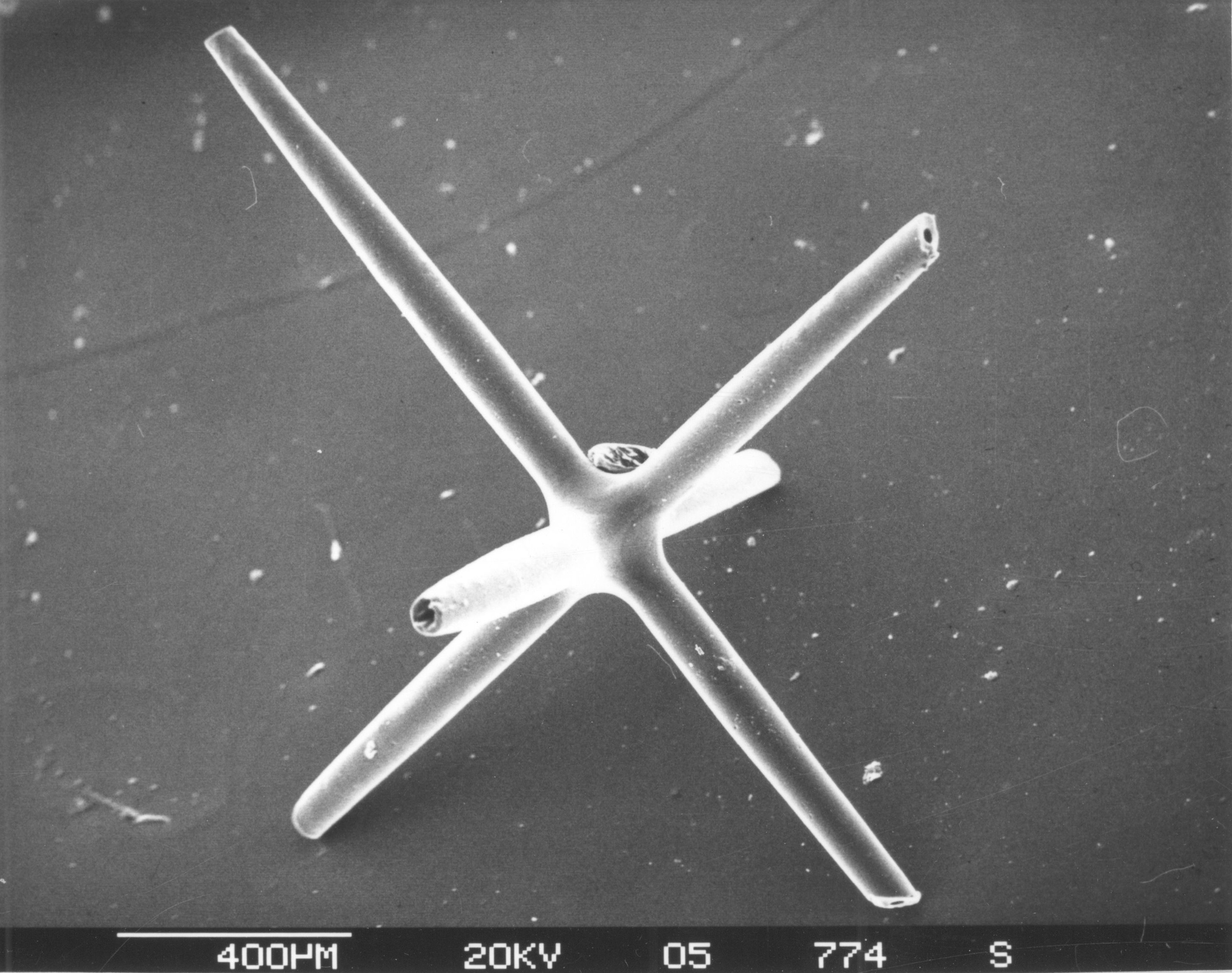

Sea sponges

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through ...

, of the phylum Porifera, are just one example of marine invertebrates who benefit from the production of secondary metabolites

Secondary metabolites, also called specialised metabolites, toxins, secondary products, or natural products, are organic compounds produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria, fungi, animals, or plants, which are not directly involved in the nor ...

. Sponges have the ability to produce their own secondary metabolites rather than rely on the storage and modification of another organism's chemical defenses. The roles of some observed secondary metabolites are still unknown; however, there is evidence highlighting that fact that a large number of secondary metabolites are used for defensive purposes. For example, there is an inverse relationship between the quantity of secondary metabolites within a sponge and the number of spicules

Spicules are any of various small needle-like anatomical structures occurring in organisms

Spicule may also refer to:

*Spicule (sponge), small skeletal elements of sea sponges

*Spicule (nematode), reproductive structures found in male nematodes ( ...

present on the organism itself. Spicules are sharp, needle-like structures protruding from the sponge and are used as a form of physical defense. Secondary metabolites and spicules have an inverse relationship because, as the quantity of secondary metabolites increase, the number of spicules decrease. This leads to the idea that secondary metabolites are indeed used for defensive purposes and sponges no longer have to rely on physical defenses. Additionally, many sponges that produce secondary metabolites are toxic to potential predators. Sponges that exhibit a larger production of secondary metabolites experience less predation, aiding in the idea that secondary metabolites are used as a defensive mechanism.

Secondary metabolite storage and modification is a useful strategy for many marine invertebrates. They are able to sequester preexisting chemicals without needing to spend the energy producing the secondary metabolites themselves. For example, Nudibranchs, also known as sea slugs, exhibit both a “passive” and an “active” form of chemical defense. Sea slugs are carnivorous and a central part of their diet consists of sea sponges who, as discussed above, produce their own defensive secondary metabolites. A key feature of sea slugs' chemical defense is their ability to store and reuse the chemicals produced by the organisms they consume. For instance, a sea sponge produces pigments which gives them their vibrant colors. The pigments in the sponges accumulate in the sea slugs as they feed, allowing the sea slug to be camouflaged within its environment. The color of the sea slug is dependent on which sponge they consume. For example, a sea slug that appears pink when found feeding on a pink sponge can turn green when migrating to a green sponge. This camouflage can be regarded as an “accidental” or passive form of chemical defense. A more active form of chemical defense found in sea slugs is their ability to store and use the defensive secondary metabolites produced by sponges. Sea slugs exhibit two mechanisms of storing defensive chemicals. The first of these mechanisms is storing the chemicals within their dorsum (or “backside”). This storage mechanism is advantageous because the defensive chemicals are located near the surface of the sea slug and are readily available for any mucus secretion. The second mechanism of defensive chemical storage exhibited by sea slugs is preserving the secondary metabolites in other areas of their body. For example, some sea slugs store secondary metabolites within their digestive track. Sea slugs who use this strategy for secondary metabolite storage have mechanisms of deploying the defensive chemicals when needed. Sea slugs are phylogenetically related to sea snails

Sea snail is a common name for slow-moving marine gastropod molluscs, usually with visible external shells, such as whelk or abalone. They share the taxonomic class Gastropoda with slugs, which are distinguished from snails primarily by the ab ...

. One of the most distinguishing factors between these two marine invertebrates is sea snails posses a shell while sea slugs do not. This loss of shell provides insight to the success of the sea slug’s chemical defensive strategies. With the use of defensive chemicals, shells are unnecessary and energetically expensive, leading to the loss of these protective structures. The fact that sea slugs can effectively survive and evade predation without the use of the shell highlights the success of storing and modifying secondary metabolites as a defensive mechanism.

The use of chemical warnings and alarms as a defensive mechanism is employed by many marine invertebrates. This mechanism relies on the invertebrates releasing and sensing chemical cues throughout their aquatic environment and modifying their behavior as a result. For example, clams have evolved to sense predator pheromones in the surrounding water and respond in a way that hides their presence from those predators. Clams

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve molluscs. The word is often applied only to those that are edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the seafloor or riverbeds. Clams have two she ...

, referring to many species of mollusks, feed by pumping. “Pumping” occurs when clams pull surrounding water in, feed on microorganisms present in the water, and release the newly filtered water. Predators of clams, namely blue shell crabs and whelks, are able to identify their prey by sensing the chemical cues present in the filtered water. Clams have evolved to chemically sense upstream predators. When a predator is sensed nearby, clams modify their behavior and discontinue their pumping to reduce consumer cues. Predators no longer have a chemical trail to follow when searching for the clam. Clams only restart their pumping when consumer cues are absent. In this scenario, both predator and prey are relying on the presence of secondary metabolites, predators are using these chemicals as a hunting mechanism while the clams are using them as an alarm that elicits their behavioral response. Blue shell crabs (Callinectes sapidus

''Callinectes sapidus'' (from the Ancient Greek ,"beautiful" + , "swimmer", and Latin , "savory"), the blue crab, Atlantic blue crab, or regionally as the Chesapeake blue crab, is a species of crab native to the waters of the western Atlantic ...

), a common predator of clams, have a similar mechanism of defense; however, instead of chemically sensing predators in the local environment, they are able to sense chemical warnings emitted by members of the same species. These crabs, when harmed, emanate a chemical warning that is species specific, meaning these chemical warnings are only detected by other blue shell crabs. These warnings can come from damaged whole crabs or body parts of the blue shell crabs. These chemical signals warn others to avoid areas of high risk. The use of chemical warnings and alarm pheromones is a mechanism used by many marine invertebrates, clams and blue shell crabs are only two examples of this defensive strategy.

Sea hares

The clade Anaspidea, commonly known as sea hares (''Aplysia'' species and related genera), are medium-sized to very large opisthobranch gastropod molluscs with a soft internal shell made of protein. These are marine gastropod molluscs in the ...

use a form of chemical defense called phagomimicry. Unlike the widespread use of the previously discussed chemical defensive strategies, phagomimicry is specific to sea hares. Phagomimicry, as the name suggests, is a type of chemical mimicry. Many organisms have evolved to use mimicry as it is a highly successful mechanism of chemical defense. Sea hares, when attacked, quickly release a fog of chemicals into the surrounding environment. The chemical cloud consists of two main parts: the ink and the opaline. The ink, when released into the water, physically obscures the sea hare from their predator. The opaline fog is a mixture of chemicals that mimic the signals of the predator's food and therefore acts as a food stimulus. The goal of the opaline chemical cloud is to supply a stronger food stimulus than the sea hare itself provides. Altogether, the cloud works to overwhelm and distract the predator. Confused, the predator will attack the chemical mixture rather than the sea hare itself, allowing time for the sea hare to escape.

Several marine invertebrates are able to acquire chemical defense by covering themselves in other organisms who possess defensive secondary metabolites. This defensive mechanism is described as "chemical clothing." Invertebrates have been observed using many different organisms as a form of clothing. These include sponges, bacteria, and seaweed. Interestingly, many marine invertebrates who capitalize on this mechanism of defense are herbivores. These herbivores choose to use seaweed as clothing rather than food, meaning they value the seaweed more for their defensive abilities rather than as potential food. In the field, invertebrates such as the Atlantic decorator crab ( Libinia dubia) experience significantly less predation when "clothed" in noxious seaweed than their unclothed conspecifics. The marine invertebrate and the chemically defended organism are able to form a symbiotic relationship resulting in the marine invertebrate acquiring long-term chemical defenses.

Vertebrates

Vertebrates can also biosynthesize defensive chemicals or sequester them from plants or prey. Sequestered compounds have been observed in frogs, natricine snakes, and two genera of birds, ''

Vertebrates can also biosynthesize defensive chemicals or sequester them from plants or prey. Sequestered compounds have been observed in frogs, natricine snakes, and two genera of birds, ''Pitohui

The pitohuis are bird species endemic to New Guinea. The onomatopoeic name is thought to be derived from that used by New Guineans from nearby Dorey (Manokwari), but it is also used as the name of a genus '' Pitohui'' which was established by the ...

'' and '' Ifrita''. It is suspected that some well-known compounds such as tetrodotoxin

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a potent neurotoxin. Its name derives from Tetraodontiformes, an order that includes pufferfish, porcupinefish, ocean sunfish, and triggerfish; several of these species carry the toxin. Although tetrodotoxin was discovere ...

produced by newt

A newt is a salamander in the subfamily Pleurodelinae. The terrestrial juvenile phase is called an eft. Unlike other members of the family Salamandridae, newts are semiaquatic, alternating between aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Not all aqua ...

s and pufferfish

Tetraodontidae is a family of primarily marine and estuarine fish of the order Tetraodontiformes. The family includes many familiar species variously called pufferfish, puffers, balloonfish, blowfish, blowies, bubblefish, globefish, swellfis ...

are derived from invertebrate prey. Bufadienolide

Bufadienolide is a chemical compound with steroid structure. Its derivatives are collectively known as bufadienolides, including many in the form of bufadienolide glycosides (bufadienolides that contain structural groups derived from sugars). Thes ...

s, defensive chemicals produced by toads, have been found in glands of natricine snakes used for defense.

Amphibians

Frogs acquire the toxins needed for chemical defense by either producing them through glands on their skin or through their diet. The source of toxins in their diet are primarilyarthropods

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chitin, ...

, ranging from beetles to millipedes. When the required dietary components are absent, such as in captivity, the frog is no longer able to produce the toxins, making them nonpoisonous. The profile of toxins may even change with the season, as is the case for the Climbing Mantella, whose diet and feeding behavior differ between wet and dry seasons

The evolutionary advantage of producing such toxins is the deterrence of predators. There is evidence to suggest that the ability to produce toxins evolved along with aposematic coloration

Aposematism is the advertising by an animal to potential predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defences which make the prey difficult to kill and eat, such as toxicity, venom, foul taste o ...

, acting as a visual cue to predators to remember which species are not palatable.

While the toxins produced by frogs are frequently referred to as poisonous, the doses of toxins are low enough that they are more noxious than poisonous. However, components of the toxins, namely the alkaloids

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

, are very active in ion channels

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of i ...

. Therefore, they disrupt the victim's nervous system, making them much more effective. Within the frogs themselves, the toxins are accumulated and delivered through small, specialized transport proteins.

Besides providing defense from predators, the toxins that poison frogs secrete interest medical researchers.

Besides providing defense from predators, the toxins that poison frogs secrete interest medical researchers. Poison dart frog

Poison dart frog (also known as dart-poison frog, poison frog or formerly known as poison arrow frog) is the common name of a group of frogs in the family Dendrobatidae which are native to tropical Central and South America. These species are ...

s, of the Dendrobatidae

Poison dart frog (also known as dart-poison frog, poison frog or formerly known as poison arrow frog) is the common name of a group of frogs in the family Dendrobatidae which are native to tropical Central and South America. These species are ...

family, secrete batrachotoxin

Batrachotoxin (BTX) is an extremely potent cardio- and neurotoxic steroidal alkaloid found in certain species of beetles, birds, and frogs. The name is from the Greek word grc, βάτραχος, bátrachos, frog, label=none. Structurally-relate ...

. This toxin has the potential to act as a muscle relaxant, heart stimulant, or anesthetic. Multiple species of frogs secrete epibatidine, whose study has yielded several important results. It was discovered that the frogs resist poisoning themselves through a single amino acid replacement that desensitizes the targeted receptors to the toxin, but still maintains the function of the receptor. This finding gives insight to the roles of proteins, the nervous system, and the mechanics of chemical defense, all of which promote future biomedical research and innovation.

Mammals

Some mammals can emit foul smelling liquids fromanal gland

Anal may refer to:

Related to the anus

*Related to the anus of animals:

** Anal fin, in fish anatomy

** Anal vein, in insect anatomy

** Anal scale, in reptile anatomy

*Related to the human anus:

** Anal sex, a type of sexual activity involving ...

s, such as the pangolin

Pangolins, sometimes known as scaly anteaters, are mammals of the order Pholidota (, from Ancient Greek ϕολιδωτός – "clad in scales"). The one extant family, the Manidae, has three genera: '' Manis'', ''Phataginus'', and '' Smuts ...

and some members of families Mephitidae and Mustelidae

The Mustelidae (; from Latin ''mustela'', weasel) are a family of carnivorous mammals, including weasels, badgers, otters, ferrets, martens, minks and wolverines, among others. Mustelids () are a diverse group and form the largest family in th ...

including skunk

Skunks are mammals in the family Mephitidae. They are known for their ability to spray a liquid with a strong, unpleasant scent from their anal glands. Different species of skunk vary in appearance from black-and-white to brown, cream or gin ...

s, weasel

Weasels are mammals of the genus ''Mustela'' of the family Mustelidae. The genus ''Mustela'' includes the least weasels, polecats, stoats, ferrets and European mink. Members of this genus are small, active predators, with long and slend ...

s, and polecat

Polecat is a common name for several mustelid species in the order Carnivora and subfamilies Ictonychinae and Mustelinae. Polecats do not form a single taxonomic rank (i.e. clade). The name is applied to several species with broad similarities ...

s. Monotreme

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals ( Eutheria), and marsupials (Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their brai ...

s have venomous spurs used to avoid predation and slow loris

Slow lorises are a group of several species of nocturnal strepsirrhine primates that make up the genus ''Nycticebus''. Found in Southeast Asia and bordering areas, they range from Bangladesh and Northeast India in the west to the Sulu Archip ...

es (Primates: Nycticebus) produce venom which appears to be effective at deterring both predators and parasites. It has also been demonstrated that physical contact with a slow loris

Slow lorises are a group of several species of nocturnal strepsirrhine primates that make up the genus ''Nycticebus''. Found in Southeast Asia and bordering areas, they range from Bangladesh and Northeast India in the west to the Sulu Archip ...

(without being bitten) can cause a reaction in humans – acting as a contact poison.

See also

* Chemical ecologyReferences

{{reflist, 30em Evolutionary biology Herbivory Predation Chemical ecology