Cesare Beccaria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, Marquis of Gualdrasco and Villareggio (; 15 March 173828 November 1794) was an Italian

Beccaria touches on an array of criminal justice practices, recommending reform. For example, he argues that dueling can be eliminated if laws protected a person from insults to his honor. Laws against suicide are ineffective, and thus should be eliminated, leaving punishment of suicide to God. Bounty hunting should not be permitted since it incites people to be immoral and shows a weakness in the government. He argues that laws should be clear in defining crimes so that judges do not interpret the law, but only decide whether a law has been broken.

Punishments should be in degree to the severity of the crime. Treason is the worst crime since it harms the social contract. This is followed by violence against a person or his property, and, finally, by public disruption. Crimes against property should be punished by fines. The best ways to prevent crimes are to enact clear and simple laws, reward virtue, and improve education.

Three tenets served as the basis of Beccaria's theories on criminal justice: free will, rational manner, and manipulability. According to Beccaria—and most classical theorists—free will enables people to make choices. Beccaria believed that people have a rational manner and apply it toward making choices that will help them achieve their own personal gratification.

In Beccaria's interpretation, law exists to preserve the social contract and benefit society as a whole. But, because people act out of self-interest and their interest sometimes conflicts with societal laws, they commit crimes. The principle of manipulability refers to the predictable ways in which people act out of rational self-interest and might therefore be dissuaded from committing crimes if the punishment outweighs the benefits of the crime, rendering the crime an illogical choice.

The principles to which Beccaria appealed were

Beccaria touches on an array of criminal justice practices, recommending reform. For example, he argues that dueling can be eliminated if laws protected a person from insults to his honor. Laws against suicide are ineffective, and thus should be eliminated, leaving punishment of suicide to God. Bounty hunting should not be permitted since it incites people to be immoral and shows a weakness in the government. He argues that laws should be clear in defining crimes so that judges do not interpret the law, but only decide whether a law has been broken.

Punishments should be in degree to the severity of the crime. Treason is the worst crime since it harms the social contract. This is followed by violence against a person or his property, and, finally, by public disruption. Crimes against property should be punished by fines. The best ways to prevent crimes are to enact clear and simple laws, reward virtue, and improve education.

Three tenets served as the basis of Beccaria's theories on criminal justice: free will, rational manner, and manipulability. According to Beccaria—and most classical theorists—free will enables people to make choices. Beccaria believed that people have a rational manner and apply it toward making choices that will help them achieve their own personal gratification.

In Beccaria's interpretation, law exists to preserve the social contract and benefit society as a whole. But, because people act out of self-interest and their interest sometimes conflicts with societal laws, they commit crimes. The principle of manipulability refers to the predictable ways in which people act out of rational self-interest and might therefore be dissuaded from committing crimes if the punishment outweighs the benefits of the crime, rendering the crime an illogical choice.

The principles to which Beccaria appealed were  Beccaria developed in his treatise a number of innovative and influential principles:

* Punishment has a preventive ( deterrent), not a retributive, function.

* Punishment should be proportionate to the crime committed.

* A high probability of punishment, not its severity, would achieve a preventive effect.

* Procedures of criminal convictions should be public.

* Finally, in order to be effective, punishment should be prompt.

He also argued against gun control laws, and was among the first to advocate the beneficial influence of education in lessening crime. Referring to gun control laws as laws based on "false ideas of utility", Beccaria wrote, "The laws of this nature are those which forbid to wear arms, disarming those only who are not disposed to commit the crime which the laws mean to prevent." He further wrote, " hese lawscertainly makes the situation of the assaulted worse, and of the assailants better, and rather encourages than prevents murder, as it requires less courage to attack unarmed than armed persons".

Beccaria developed in his treatise a number of innovative and influential principles:

* Punishment has a preventive ( deterrent), not a retributive, function.

* Punishment should be proportionate to the crime committed.

* A high probability of punishment, not its severity, would achieve a preventive effect.

* Procedures of criminal convictions should be public.

* Finally, in order to be effective, punishment should be prompt.

He also argued against gun control laws, and was among the first to advocate the beneficial influence of education in lessening crime. Referring to gun control laws as laws based on "false ideas of utility", Beccaria wrote, "The laws of this nature are those which forbid to wear arms, disarming those only who are not disposed to commit the crime which the laws mean to prevent." He further wrote, " hese lawscertainly makes the situation of the assaulted worse, and of the assailants better, and rather encourages than prevents murder, as it requires less courage to attack unarmed than armed persons".

"Cesare Beccaria: Functionary, Lecturer, Cameralist?: Interpreting Cameralism in Habsburg Lombardy."

''Cameralism and the Enlightenment''. Routledge, 2019. 173-200.

a

McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria

a

Online Library of Liberty

*

Works

a

Open Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Beccaria 1738 births 1794 deaths Enlightenment philosophers Italian jurists 18th-century Italian jurists 18th-century Italian philosophers Writers from Milan Margraves of Italy 18th-century jurists Duchy of Milan people Italian criminologists

criminologist

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and so ...

, jurist, philosopher, economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this field there are ...

and politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking ...

, who is widely considered one of the greatest thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. He is well remembered for his treatise '' On Crimes and Punishments'' (1764), which condemned torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

and the death penalty, and was a founding work in the field of penology

Penology (from "penal", Latin '' poena'', "punishment" and the Greek suffix '' -logia'', "study of") is a sub-component of criminology that deals with the philosophy and practice of various societies in their attempts to repress criminal activiti ...

and the Classical School of criminology. Beccaria is considered the father of modern criminal law and the father of criminal justice

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other ...

.

According to John Bessler, Beccaria's works had a profound influence on the Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American Revolution, American revolutionary leaders who United Colonies, united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the Am ...

.

Birth and education

Beccaria was born inMilan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

on 15 March 1738 to the Marchese Gian Beccaria Bonesana, an aristocrat of moderate standing from the Austrian Habsburg Empire

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

. Beccaria received his early education in the Jesuit college at Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, music, art, prosciutto (ham), cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 inhabitants, Parma is the second mos ...

. Subsequently, he graduated in law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

from the University of Pavia

The University of Pavia ( it, Università degli Studi di Pavia, UNIPV or ''Università di Pavia''; la, Alma Ticinensis Universitas) is a university located in Pavia, Lombardy, Italy. There was evidence of teaching as early as 1361, making it one ...

in 1758. At first he showed a great aptitude for mathematics, but studying Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

(1689–1755) redirected his attention towards economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyzes ...

. In 1762 his first publication, a tract on the disorder of the currency in the Milanese states, included a proposal for its remedy.

In his mid-twenties, Beccaria became close friends with Pietro and Alessandro Verri, two brothers who with a number of other young men from the Milan aristocracy, formed a literary society named "L'Accademia dei pugni" (the Academy of Fists), a playful name which made fun of the stuffy academies that proliferated in Italy and also hinted that relaxed conversations which took place in there sometimes ended in affray

In many legal jurisdictions related to English common law, affray is a public order offence consisting of the fighting of one or more persons in a public place to the terror (in french: à l'effroi) of ordinary people. Depending on their act ...

s. Much of its discussion focused on reforming the criminal justice system. Through this group Beccaria became acquainted with French and British political philosophers, such as Diderot, Helvétius, Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

, and Hume. He was particularly influenced by Helvétius.

''On Crimes and Punishments''

Cesare Beccaria was best known for his book on crimes and punishments. In 1764, with the encouragement of Pietro Verri, Beccaria published a brief but celebrated treatise '' On Crimes and Punishments''. Some background information was provided by Pietro, who was writing a text on the history of torture, and Alessandro Verri, a Milan prison official who had firsthand experience of the prison's appalling conditions. In this essay, Beccaria reflected the convictions of his friends in the '' Il Caffè'' (Coffee House) group, who sought reform through Enlightenment discourse. Beccaria's treatise marked the high point of the Milan Enlightenment. In it, Beccaria put forth some of the first modern arguments against the death penalty. His treatise was also the first full work ofpenology

Penology (from "penal", Latin '' poena'', "punishment" and the Greek suffix '' -logia'', "study of") is a sub-component of criminology that deals with the philosophy and practice of various societies in their attempts to repress criminal activiti ...

, advocating reform of the criminal law system. The book was the first full-scale work to tackle criminal reform and to suggest that criminal justice should conform to rational principles. It is a less theoretical work than the writings of Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf and other comparable thinkers, and as much a work of advocacy as of theory.

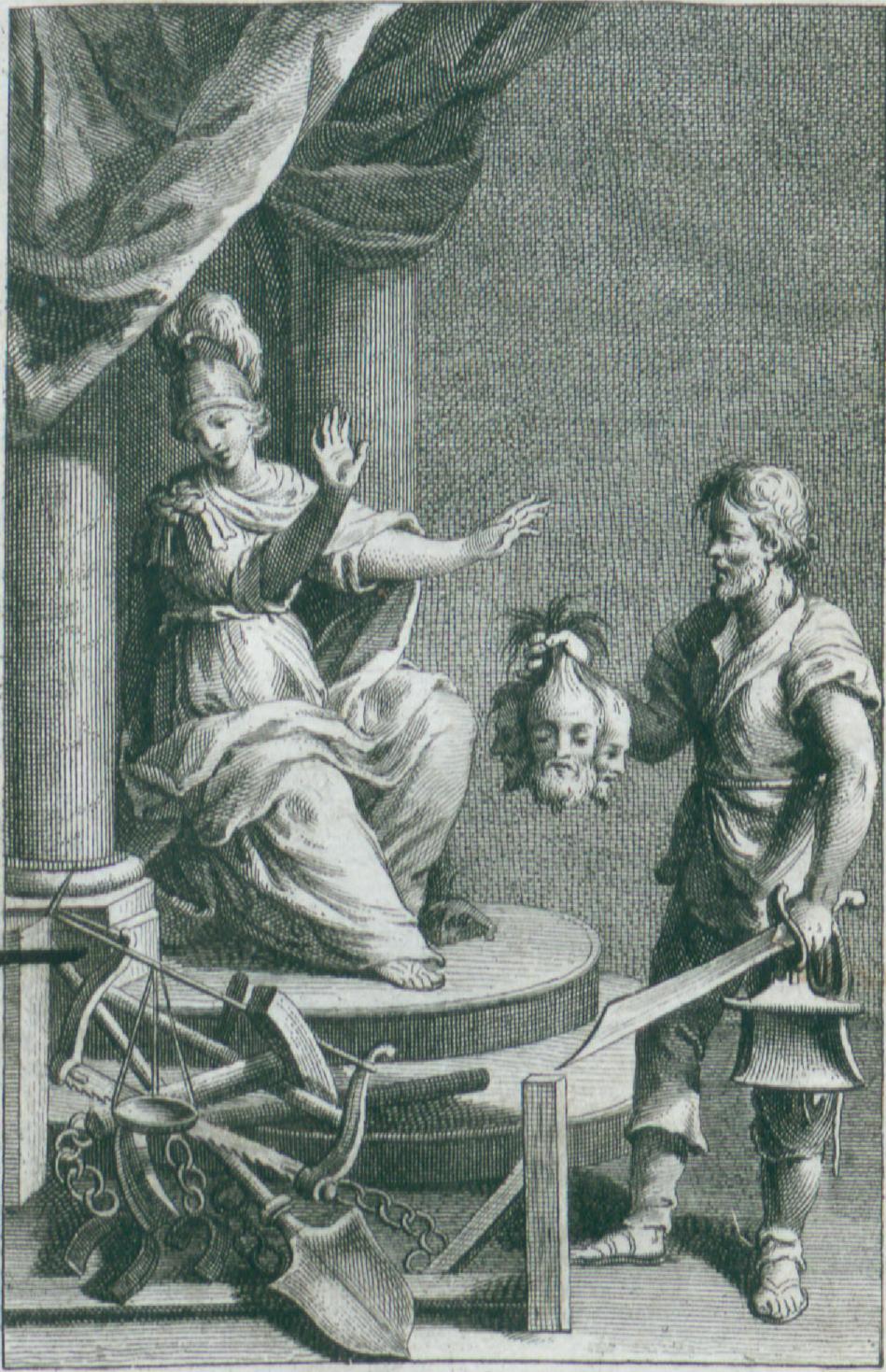

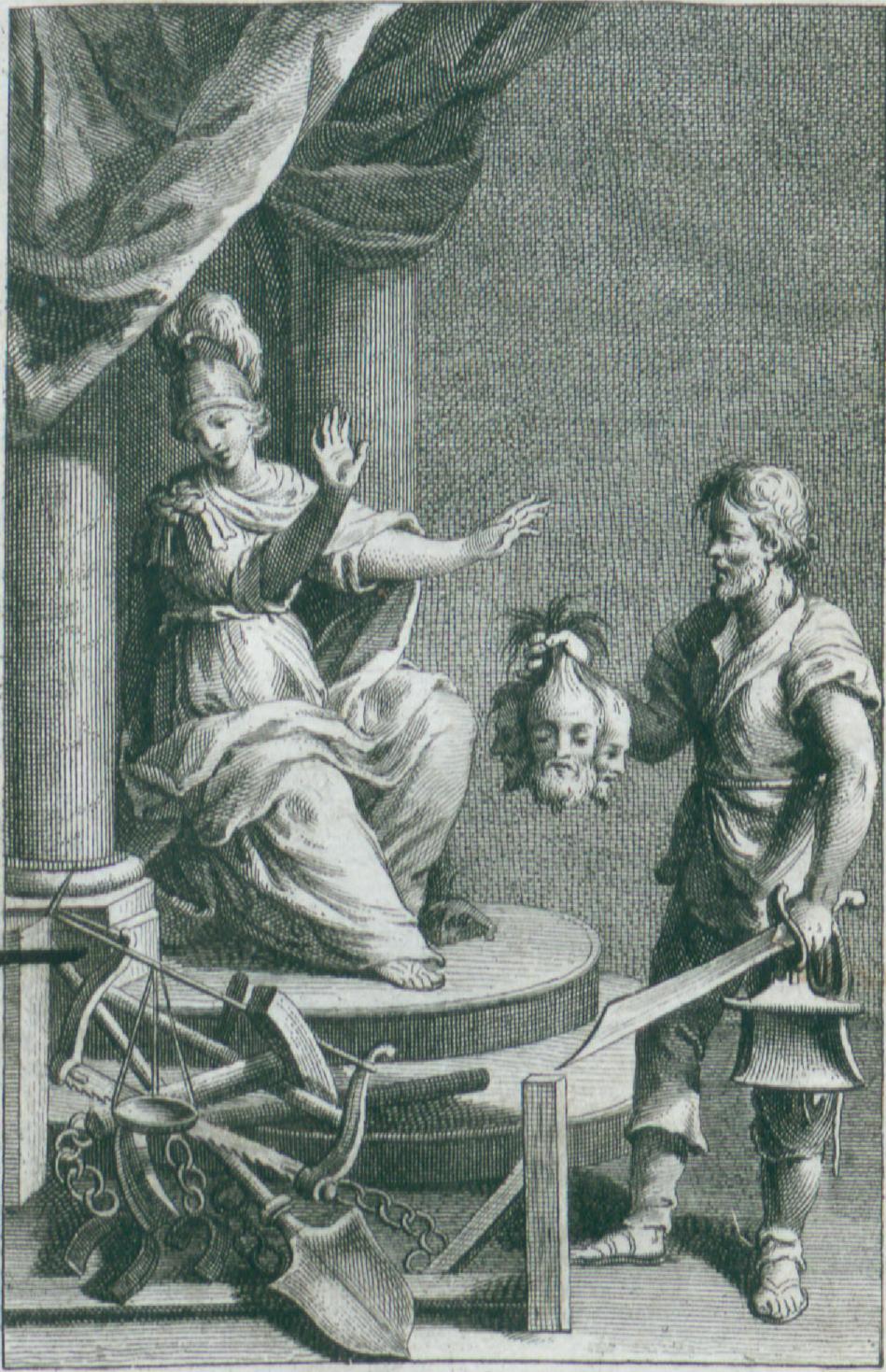

The brief work relentlessly protests against torture to obtain confessions, secret accusations, the arbitrary discretionary power of judges, the inconsistency and inequality of sentencing, using personal connections to get a lighter sentence, and the use of capital punishment for serious and even minor offences.

Almost immediately, the work was translated into French and English and went through several editions. Editions of Beccaria's text follow two distinct arrangements of the material: that by Beccaria himself, and that by French translator André Morellet (1765) who imposed a more systematic order. Morellet felt the Italian text required clarification, and therefore omitted parts, made some additions, and above all restructured the essay by moving, merging or splitting chapters. Because Beccaria indicated in a letter to Morellet that he fully agreed with him, scholars assumed that these adaptations also had Beccaria's consent in substance. The differences are so great, however, that Morellet’s version became quite another book than the book that Beccaria wrote.

Beccaria opens his work describing the great need for reform in the criminal justice system, and he observes how few studies there are on the subject of such reform. Throughout his work, Beccaria develops his position by appealing to two key philosophical theories: social contract and utility. Concerning the social contract, Beccaria argues that punishment is justified only to defend the social contract and to ensure that everyone will be motivated to abide by it. Concerning utility (perhaps influenced by Helvetius), Beccaria argues that the method of punishment selected should be that which serves the greatest public good.

Contemporary political philosophers distinguish between two principal theories of justifying punishment. First, the retributive approach maintains that punishment should be equal to the harm done, either literally an eye for an eye, or more figuratively which allows for alternative forms of compensation. The retributive approach tends to be retaliatory and vengeance-oriented. The second approach is utilitarian which maintains that punishment should increase the total amount of happiness in the world. This often involves punishment as a means of reforming the criminal, incapacitating him from repeating his crime, and deterring others. Beccaria clearly takes a utilitarian stance. For Beccaria, the purpose of punishment is to create a better society, not revenge. Punishment serves to deter others from committing crimes, and to prevent the criminal from repeating his crime.

Beccaria argues that punishment should be close in time to the criminal action to maximize the punishment's deterrence value. He defends his view about the temporal proximity of punishment by appealing to the associative theory of understanding in which our notions of causes and the subsequently perceived effects are a product of our perceived emotions that form from our observations of a causes and effect occurring in close correspondence (for more on this topic, see David Hume's work on the problem of induction, as well as the works of David Hartley). Thus, by avoiding punishments that are remote in time from the criminal action, we are able to strengthen the association between the criminal behavior and the resulting punishment which, in turn, discourages the criminal activity.

For Beccaria when a punishment quickly follows a crime, then the two ideas of "crime" and "punishment" will be more closely associated in a person's mind. Also, the link between a crime and a punishment is stronger if the punishment is somehow related to the crime. Given the fact that the swiftness of punishment has the greatest impact on deterring others, Beccaria argues that there is no justification for severe punishments. In time we will naturally grow accustomed to increases in severity of punishment, and, thus, the initial increase in severity will lose its effect. There are limits both to how much torment we can endure, and also how much we can inflict.

Beccaria touches on an array of criminal justice practices, recommending reform. For example, he argues that dueling can be eliminated if laws protected a person from insults to his honor. Laws against suicide are ineffective, and thus should be eliminated, leaving punishment of suicide to God. Bounty hunting should not be permitted since it incites people to be immoral and shows a weakness in the government. He argues that laws should be clear in defining crimes so that judges do not interpret the law, but only decide whether a law has been broken.

Punishments should be in degree to the severity of the crime. Treason is the worst crime since it harms the social contract. This is followed by violence against a person or his property, and, finally, by public disruption. Crimes against property should be punished by fines. The best ways to prevent crimes are to enact clear and simple laws, reward virtue, and improve education.

Three tenets served as the basis of Beccaria's theories on criminal justice: free will, rational manner, and manipulability. According to Beccaria—and most classical theorists—free will enables people to make choices. Beccaria believed that people have a rational manner and apply it toward making choices that will help them achieve their own personal gratification.

In Beccaria's interpretation, law exists to preserve the social contract and benefit society as a whole. But, because people act out of self-interest and their interest sometimes conflicts with societal laws, they commit crimes. The principle of manipulability refers to the predictable ways in which people act out of rational self-interest and might therefore be dissuaded from committing crimes if the punishment outweighs the benefits of the crime, rendering the crime an illogical choice.

The principles to which Beccaria appealed were

Beccaria touches on an array of criminal justice practices, recommending reform. For example, he argues that dueling can be eliminated if laws protected a person from insults to his honor. Laws against suicide are ineffective, and thus should be eliminated, leaving punishment of suicide to God. Bounty hunting should not be permitted since it incites people to be immoral and shows a weakness in the government. He argues that laws should be clear in defining crimes so that judges do not interpret the law, but only decide whether a law has been broken.

Punishments should be in degree to the severity of the crime. Treason is the worst crime since it harms the social contract. This is followed by violence against a person or his property, and, finally, by public disruption. Crimes against property should be punished by fines. The best ways to prevent crimes are to enact clear and simple laws, reward virtue, and improve education.

Three tenets served as the basis of Beccaria's theories on criminal justice: free will, rational manner, and manipulability. According to Beccaria—and most classical theorists—free will enables people to make choices. Beccaria believed that people have a rational manner and apply it toward making choices that will help them achieve their own personal gratification.

In Beccaria's interpretation, law exists to preserve the social contract and benefit society as a whole. But, because people act out of self-interest and their interest sometimes conflicts with societal laws, they commit crimes. The principle of manipulability refers to the predictable ways in which people act out of rational self-interest and might therefore be dissuaded from committing crimes if the punishment outweighs the benefits of the crime, rendering the crime an illogical choice.

The principles to which Beccaria appealed were Reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

, an understanding of the state as a form of contract, and, above all, the principle of utility, or of the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Beccaria had elaborated this original principle in conjunction with Pietro Verri

Count Pietro Verri (12 December 1728 – 28 June 1797) was an economist, historian, philosopher and writer. Among the most important personalities of the 18th-century Italian culture, he is considered among the fathers of the Lombard reformist E ...

, and greatly influenced Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

to develop it into the full-scale doctrine of Utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

.

He openly condemned the death penalty on two grounds:

# because the state does not possess the right to take lives; and

# because capital punishment is neither a useful nor a necessary form of punishment.

Beccaria developed in his treatise a number of innovative and influential principles:

* Punishment has a preventive ( deterrent), not a retributive, function.

* Punishment should be proportionate to the crime committed.

* A high probability of punishment, not its severity, would achieve a preventive effect.

* Procedures of criminal convictions should be public.

* Finally, in order to be effective, punishment should be prompt.

He also argued against gun control laws, and was among the first to advocate the beneficial influence of education in lessening crime. Referring to gun control laws as laws based on "false ideas of utility", Beccaria wrote, "The laws of this nature are those which forbid to wear arms, disarming those only who are not disposed to commit the crime which the laws mean to prevent." He further wrote, " hese lawscertainly makes the situation of the assaulted worse, and of the assailants better, and rather encourages than prevents murder, as it requires less courage to attack unarmed than armed persons".

Beccaria developed in his treatise a number of innovative and influential principles:

* Punishment has a preventive ( deterrent), not a retributive, function.

* Punishment should be proportionate to the crime committed.

* A high probability of punishment, not its severity, would achieve a preventive effect.

* Procedures of criminal convictions should be public.

* Finally, in order to be effective, punishment should be prompt.

He also argued against gun control laws, and was among the first to advocate the beneficial influence of education in lessening crime. Referring to gun control laws as laws based on "false ideas of utility", Beccaria wrote, "The laws of this nature are those which forbid to wear arms, disarming those only who are not disposed to commit the crime which the laws mean to prevent." He further wrote, " hese lawscertainly makes the situation of the assaulted worse, and of the assailants better, and rather encourages than prevents murder, as it requires less courage to attack unarmed than armed persons". Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

noted this passage in his "Legal Commonplace Book

Commonplace books (or commonplaces) are a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. They have been kept from antiquity, and were kept particularly during the Renaissance and in the nineteenth century. Such books are simi ...

".

As Beccaria's ideas were critical of the legal system in place at the time, and were therefore likely to stir controversy, he chose to publish the essay anonymously, for fear of government backlash. Among his contemporary critics, was Antonio Silla

Biography

He was born in Scanno, Abruzzo, Scanno in the region of the Abruzzo, but then belonging to the kingdom of Naples. He was born to a well-to-do family invested in herding animals. He initially studied under the Jesuits in Chieti, but moved ...

, writing from Naples.

In the event, the treatise was extremely well received. Catherine the Great publicly endorsed it, while thousands of miles away in the United States, founding fathers Thomas Jefferson and John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

quoted it. Once it was clear that the government approved of his essay, Beccaria republished it, this time crediting himself as the author.

Later life and influence

With much hesitation, Beccaria accepted an invitation to Paris to meet the great thinkers of the day. He travelled with the Verri brothers and was given a warm reception by the ''philosophes

The ''philosophes'' () were the intellectuals of the 18th-century Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosophe ...

''. However, the chronically-shy Beccaria made a poor impression and left after three weeks, returning to Milan and to his young wife Teresa and never venturing abroad again. The break with the Verri brothers proved lasting; they were never able to understand why Beccaria had left his position at the peak of success.

Beccaria nevertheless continued to command official recognition, and he was appointed to several nominal political positions in Italy. Separated from the invaluable input of his friends, he failed to produce another text of equal importance. Outside Italy, an unfounded myth grew that Beccaria's literary silence resulted from Austrian restrictions on free expression in Italy. In fact, prone to periodic bouts of depression and misanthropy, he had grown silent on his own.

Legal scholars of the time hailed Beccaria's treatise, and several European emperors vowed to follow it. Many reforms in the penal codes of the principal European nations can be traced to the treatise, but few contemporaries were convinced by Beccaria's argument against the death penalty. Even when the Grand Duchy of Tuscany abolished the death penalty, the first nation in the world to do so, it followed Beccaria's argument about the lack of utility of capital punishment, not about the state's lacking the right to execute citizens. In the anglophone world, Beccaria's ideas fed into the writings on punishment of Sir William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family ...

(selectively), and more wholeheartedly those of William Eden and Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

.

In November 1768, he was appointed to the chair of law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

and economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

founded expressly for him at the Palatine College of Milan. His lectures on political economy, which are based on strict utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

principles, are in marked accordance with the theories of the English school of economists. They are published in the collection of Italian writers on political economy (''Scrittori Classici Italiani di Economia politica'', vols. xi. and xii.). Beccaria never succeeded in producing another work to match ''Dei Delitti e Delle Pene'', but he made various incomplete attempts in the course of his life. A short treatise on literary style was all he saw to press.

In 1771, Beccaria was made a member of the supreme economic council, and in 1791 he was appointed to the board for the reform of the judicial code, where he made a valuable contribution. During this period he spearheaded a number of important reforms, such as the standardisation of weights and measurements. He died in Milan.

A pioneer in criminology, his influence during his lifetime extended to shaping the rights listed in the US Constitution and Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pr ...

. ''On Crimes and Punishments'' served as a useful guide to the founding fathers.

Beccaria's theories, as expressed in ''On Crimes and Punishments'', have continued to play a great role in recent times. Some of the current policies impacted by his theories are truth in sentencing, swift punishment and the abolishment of the death penalty in some U.S. states. While many of his theories are popular, some are still a source of heated controversy, even more than two centuries after the famed criminologist's death.

Family

Beccaria's grandson wasAlessandro Manzoni

Alessandro Francesco Tommaso Antonio Manzoni (, , ; 7 March 1785 – 22 May 1873) was an Italian poet, novelist and philosopher. He is famous for the novel '' The Betrothed'' (orig. it, I promessi sposi) (1827), generally ranked among the maste ...

, the noted Italian novelist and poet who wrote, among other things, '' The Betrothed'', one of the first Italian historical novels, and "Il cinque maggio", a poem on Napoleon's death.

Commemorations

* Beccaria Township in centralPennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, United States, is named for him.

* Piazza Beccaria, a large square in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, Italy, is also named for him.

See also

* Capital punishment in ItalyReferences

Further reading

* * * *Ortolja-Baird, Alexandra"Cesare Beccaria: Functionary, Lecturer, Cameralist?: Interpreting Cameralism in Habsburg Lombardy."

''Cameralism and the Enlightenment''. Routledge, 2019. 173-200.

External links

* * *a

McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria

a

Online Library of Liberty

*

Works

a

Open Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Beccaria 1738 births 1794 deaths Enlightenment philosophers Italian jurists 18th-century Italian jurists 18th-century Italian philosophers Writers from Milan Margraves of Italy 18th-century jurists Duchy of Milan people Italian criminologists