Cerberus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

In art Cerberus is most commonly depicted with two dog heads (visible), never more than three, but occasionally with only one. On one of the two earliest depictions (c. 590–580 BC), a

In art Cerberus is most commonly depicted with two dog heads (visible), never more than three, but occasionally with only one. On one of the two earliest depictions (c. 590–580 BC), a

Cerberus' only mythology concerns his capture by Heracles. As early as

Cerberus' only mythology concerns his capture by Heracles. As early as

There are various versions of how Heracles accomplished Cerberus' capture. According to Apollodorus, Heracles asked Hades for Cerberus, and Hades told Heracles he would allow him to take Cerberus only if he "mastered him without the use of the weapons which he carried", and so, using his lion-skin as a shield, Heracles squeezed Cerberus around the head until he submitted.

In some early sources Cerberus' capture seems to involve Heracles fighting Hades. Homer (''Iliad'' 5.395–397) has Hades injured by an arrow shot by Heracles. A scholium to the ''Iliad'' passage, explains that Hades had commanded that Heracles "master Cerberus without shield or Iron". Heracles did this, by (as in Apollodorus) using his lion-skin instead of his shield, and making stone points for his arrows, but when Hades still opposed him, Heracles shot Hades in anger. Consistent with the no iron requirement, on an early-sixth-century BC lost Corinthian cup, Heracles is shown attacking Hades with a stone, while the iconographic tradition, from c. 560 BC, often shows Heracles using his wooden club against Cerberus.

Euripides has Amphitryon ask Heracles: "Did you conquer him in fight, or receive him from the goddess .e. Persephone To which Heracles answers: "In fight", and the ''Pirithous'' fragment says that Heracles "overcame the beast by force". However, according to Diodorus, Persephone welcomed Heracles "like a brother" and gave Cerberus "in chains" to Heracles. Aristophanes has Heracles seize Cerberus in a stranglehold and run off, while Seneca has Heracles again use his lion-skin as shield, and his wooden club, to subdue Cerberus, after which a quailing Hades and Persephone allow Heracles to lead a chained and submissive Cerberus away. Cerberus is often shown being chained, and Ovid tells that Heracles dragged the three headed Cerberus with chains of

There are various versions of how Heracles accomplished Cerberus' capture. According to Apollodorus, Heracles asked Hades for Cerberus, and Hades told Heracles he would allow him to take Cerberus only if he "mastered him without the use of the weapons which he carried", and so, using his lion-skin as a shield, Heracles squeezed Cerberus around the head until he submitted.

In some early sources Cerberus' capture seems to involve Heracles fighting Hades. Homer (''Iliad'' 5.395–397) has Hades injured by an arrow shot by Heracles. A scholium to the ''Iliad'' passage, explains that Hades had commanded that Heracles "master Cerberus without shield or Iron". Heracles did this, by (as in Apollodorus) using his lion-skin instead of his shield, and making stone points for his arrows, but when Hades still opposed him, Heracles shot Hades in anger. Consistent with the no iron requirement, on an early-sixth-century BC lost Corinthian cup, Heracles is shown attacking Hades with a stone, while the iconographic tradition, from c. 560 BC, often shows Heracles using his wooden club against Cerberus.

Euripides has Amphitryon ask Heracles: "Did you conquer him in fight, or receive him from the goddess .e. Persephone To which Heracles answers: "In fight", and the ''Pirithous'' fragment says that Heracles "overcame the beast by force". However, according to Diodorus, Persephone welcomed Heracles "like a brother" and gave Cerberus "in chains" to Heracles. Aristophanes has Heracles seize Cerberus in a stranglehold and run off, while Seneca has Heracles again use his lion-skin as shield, and his wooden club, to subdue Cerberus, after which a quailing Hades and Persephone allow Heracles to lead a chained and submissive Cerberus away. Cerberus is often shown being chained, and Ovid tells that Heracles dragged the three headed Cerberus with chains of

There were several locations which were said to be the place where Heracles brought up Cerberus from the underworld. The geographer Strabo (63/64 BC – c. AD 24) reports that "according to the myth writers" Cerberus was brought up at Tainaron, the same place where Euripides has Heracles enter the underworld. Seneca has Heracles enter and exit at Tainaron. Apollodorus, although he has Heracles enter at Tainaron, has him exit at

There were several locations which were said to be the place where Heracles brought up Cerberus from the underworld. The geographer Strabo (63/64 BC – c. AD 24) reports that "according to the myth writers" Cerberus was brought up at Tainaron, the same place where Euripides has Heracles enter the underworld. Seneca has Heracles enter and exit at Tainaron. Apollodorus, although he has Heracles enter at Tainaron, has him exit at

The earliest mentions of Cerberus (c. 8th – 7th century BC) occur in

The earliest mentions of Cerberus (c. 8th – 7th century BC) occur in

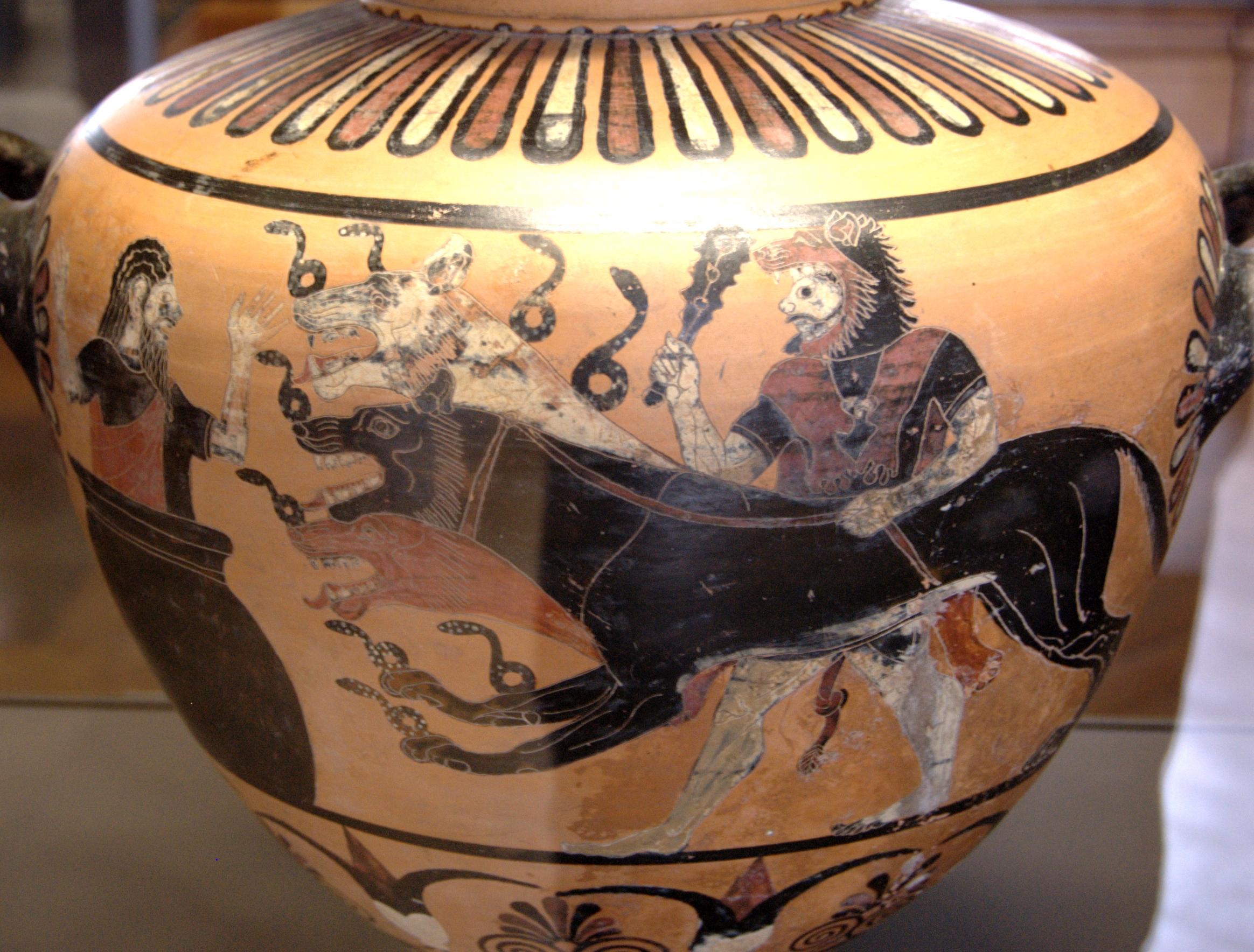

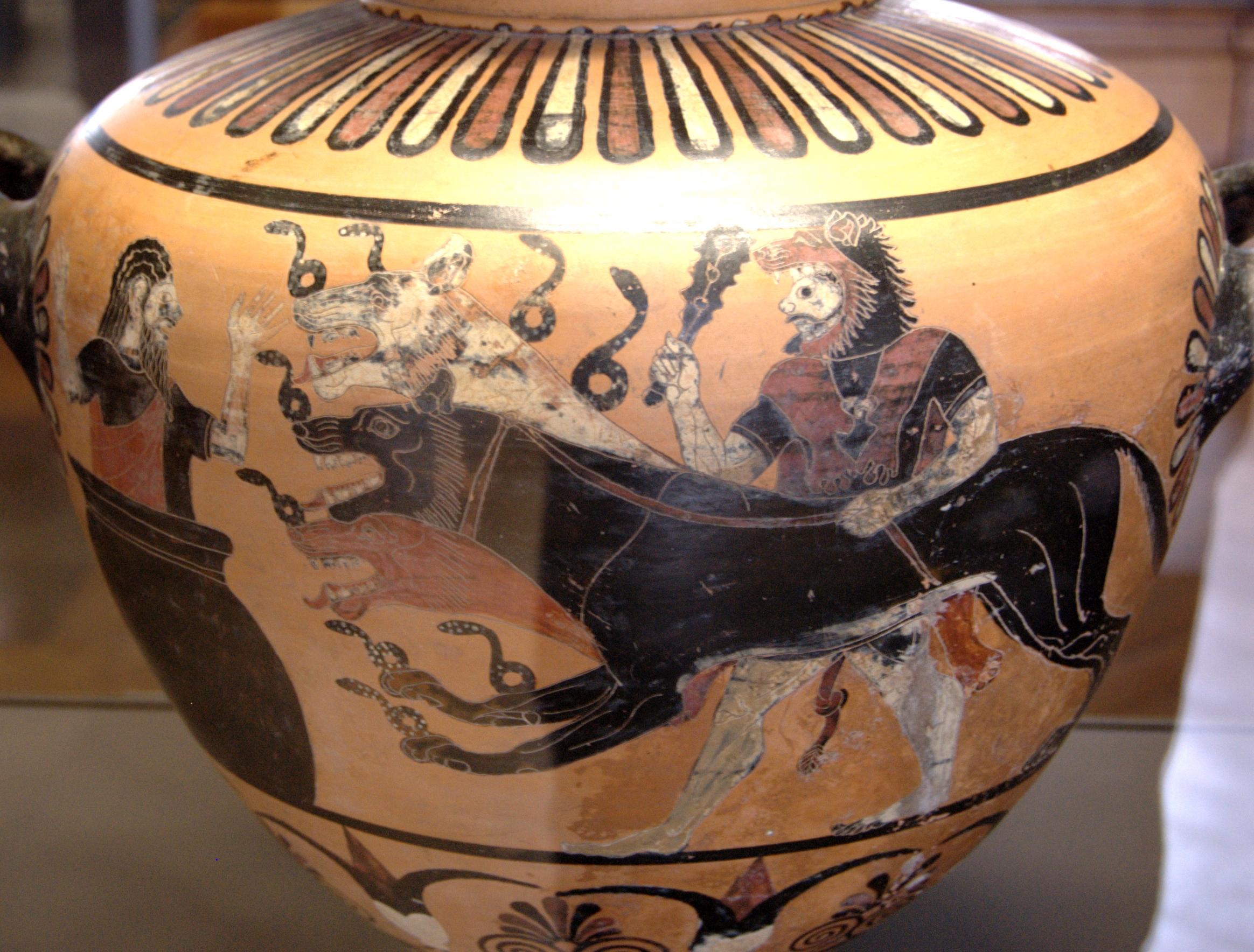

The capture of Cerberus was a popular theme in ancient Greek and Roman art. The earliest depictions date from the beginning of the sixth century BC. One of the two earliest depictions, a

The capture of Cerberus was a popular theme in ancient Greek and Roman art. The earliest depictions date from the beginning of the sixth century BC. One of the two earliest depictions, a  As in the Corinthian and Laconian cups (and possibly the relief ''pithos'' fragment), Cerberus is often depicted as part snake. In Attic vase painting, Cerberus is usually shown with a snake for a tail or a tail which ends in the head of a snake. Snakes are also often shown rising from various parts of his body including snout, head, neck, back, ankles, and paws.

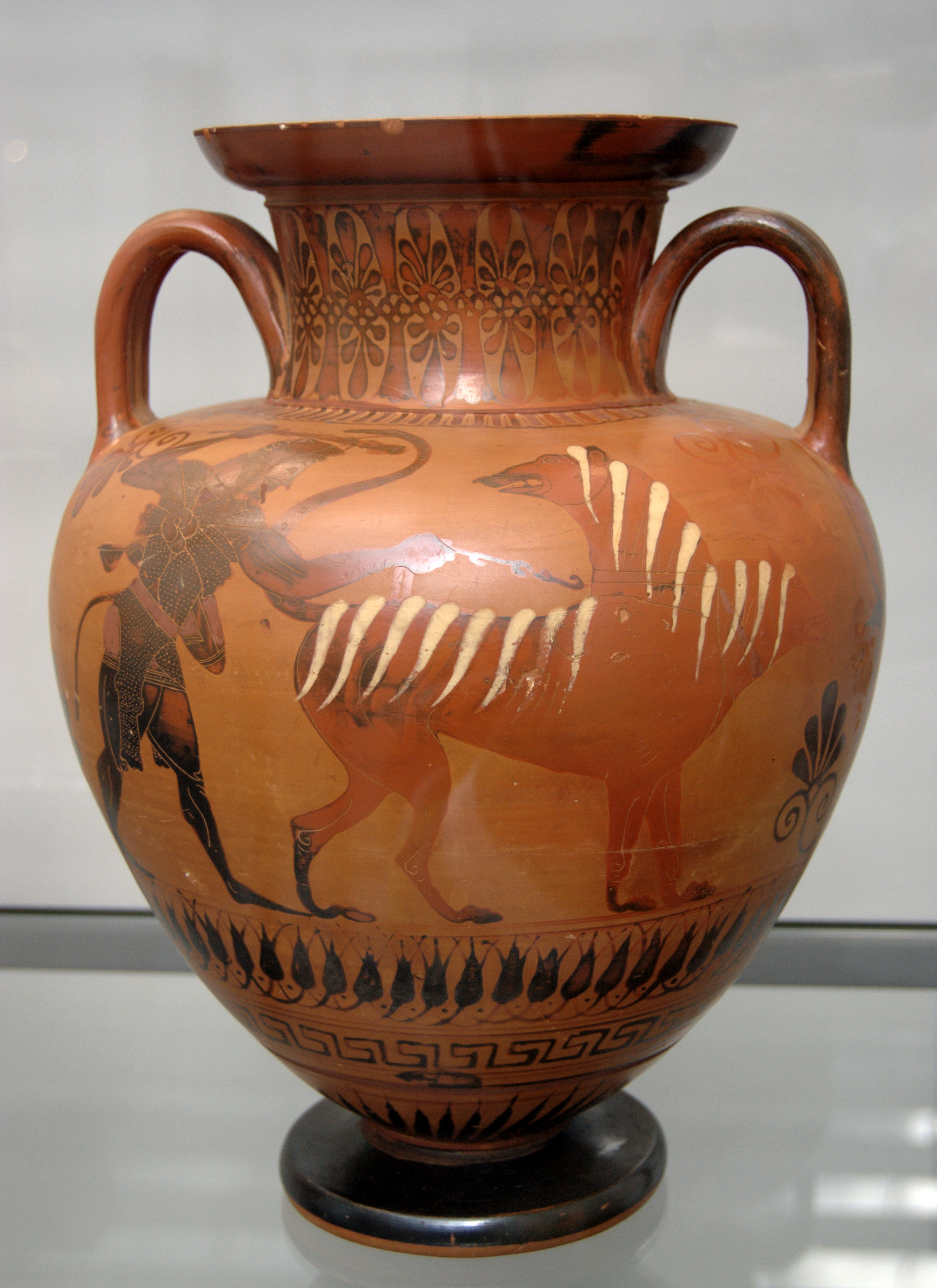

Two Attic amphoras from Vulci, one (c. 530–515 BC) by the Bucci Painter (Munich 1493), the other (c. 525–510 BC) by the Andokides painter (Louvre F204), in addition to the usual two heads and snake tail, show Cerberus with a mane down his necks and back, another typical Cerberian feature of Attic vase painting. Andokides' amphora also has a small snake curling up from each of Cerberus' two heads.

Besides this lion-like mane and the occasional lion-head mentioned above, Cerberus was sometimes shown with other leonine features. A pitcher (c. 530–500) shows Cerberus with mane and claws, while a first-century BC

As in the Corinthian and Laconian cups (and possibly the relief ''pithos'' fragment), Cerberus is often depicted as part snake. In Attic vase painting, Cerberus is usually shown with a snake for a tail or a tail which ends in the head of a snake. Snakes are also often shown rising from various parts of his body including snout, head, neck, back, ankles, and paws.

Two Attic amphoras from Vulci, one (c. 530–515 BC) by the Bucci Painter (Munich 1493), the other (c. 525–510 BC) by the Andokides painter (Louvre F204), in addition to the usual two heads and snake tail, show Cerberus with a mane down his necks and back, another typical Cerberian feature of Attic vase painting. Andokides' amphora also has a small snake curling up from each of Cerberus' two heads.

Besides this lion-like mane and the occasional lion-head mentioned above, Cerberus was sometimes shown with other leonine features. A pitcher (c. 530–500) shows Cerberus with mane and claws, while a first-century BC

The etymology of Cerberus' name is uncertain. Ogden refers to attempts to establish an Indo-European etymology as "not yet successful". It has been claimed to be related to the

The etymology of Cerberus' name is uncertain. Ogden refers to attempts to establish an Indo-European etymology as "not yet successful". It has been claimed to be related to the

Servius, a medieval commentator on

Servius, a medieval commentator on

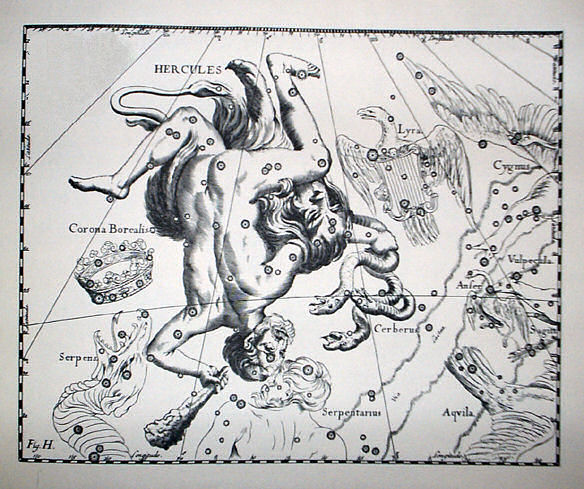

In the constellation Cerberus introduced by

In the constellation Cerberus introduced by

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at Harvard University Press

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Bloomfield, Maurice, ''Cerberus, the Dog of Hades: The History of an Idea'', Open Court publishing Company, 1905

Online version at Internet Archive

* Bowra, C. M., ''Greek Lyric Poetry: From Alcman to Simonides'', Clarendon Press, 2001. . * Diodorus Siculus, ''Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History''. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. *

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Fowler, R. L. (2000), ''Early Greek Mythography: Volume 1: Text and Introduction'', Oxford University Press, 2000. . * Fowler, R. L. (2013), ''Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary'', Oxford University Press, 2013. . * Freeman, Kathleen, ''Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels, Fragmente Der Vorsokratiker'', Harvard University Press, 1983. . * Gantz, Timothy, ''Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: (Vol. 1), (Vol. 2). * Hard, Robin, ''The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology"'', Psychology Press, 2004,

Google Books

* Harding, Phillip, ''The Story of Athens: The Fragments of the Local Chronicles of Attika'', Routledge, 2007. . * Hawes, Greta, ''Rationalizing Myth in Antiquity'', OUP Oxford, 2014. . *

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Hopman, Marianne Govers, ''Scylla: Myth, Metaphor, Paradox'', Cambridge University Press, 2013. . * Horace, ''The Odes and Carmen Saeculare of Horace''. John Conington. trans. London. George Bell and Sons. 1882

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Hyginus, Gaius Julius

''The Myths of Hyginus''

Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. * Kirk, G. S. 1990 ''The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume 2, Books 5–8'', . * Lansing, Richard (editor), ''The Dante Encyclopedia'', Routledge, 2010. . * Lightfoot, J. L. ''Hellenistic Collection: Philitas. Alexander of Aetolia. Hermesianax. Euphorion. Parthenius''. Edited and translated by J. L. Lightfoot. Loeb Classical Library No. 508. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Online version at Harvard University Press

* * Lucan, ''Pharsalia'', Sir Edward Ridley. London. Longmans, Green, and Co. 1905

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Markantonatos, Andreas, ''Tragic Narrative: A Narratological Study of Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus'', Walter de Gruyter, 2002. . * Nimmo Smith, Jennifer, ''A Christian's Guide to Greek Culture: The Pseudo-nonnus Commentaries on Sermons 4, 5, 39 and 43''. Liverpool University Press, 2001. . * Ogden, Daniel (2013a), ''Drakōn: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds'', Oxford University Press, 2013. . * Ogden, Daniel (2013b), ''Dragons, Serpents, and Slayers in the Classical and early Christian Worlds: A sourcebook'', Oxford University Press. . *

Online version at Harvard University Press

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Papadopoulou, Thalia, ''Heracles and Euripidean Tragedy'', Cambridge University Press, 2005. . *

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Pepin, Ronald E., ''The Vatican Mythographers'', Fordham University Press, 2008. *

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* Pipili, Maria, ''Laconian Iconography of the Sixth Century B.C.'', Oxford University, 1987. *

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

''Theseus'' at the Perseus Digital Library

* Propertius ''Elegies'' Edited and translated by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library 18. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Online version at Harvard University Press

* Quintus Smyrnaeus, ''Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy'', Translator: A.S. Way; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1913

Internet Archive

* Room, Adrian, ''Who's Who in Classical Mythology'', Gramercy Books, 2003. . * Schefold, Karl (1966), ''Myth and Legend in Early Greek Art'', London, Thames and Hudson. * Schefold, Karl (1992), ''Gods and Heroes in Late Archaic Greek Art'', assisted by Luca Giuliani, Cambridge University Press, 1992. . *

Online version at Harvard University Press

*

Online version at Harvard University Press

* Smallwood, Valerie, "M. Herakles and Kerberos (Labour XI)" in ''

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Internet Archive

*

Internet Archive

* Stern, Jacob, ''Palaephatus Πεπὶ Ὰπίστων, On Unbelievable Tales'', Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1996. . * Trypanis, C. A., Gelzer, Thomas; Whitman, Cedric, ''CALLIMACHUS, MUSAEUS, Aetia, Iambi, Hecale and Other Fragments. Hero and Leander'', Harvard University Press, 1975. . *

Internet Archive

. *

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

* West, David, ''Horace, Odes 3'', Oxford University Press, 2002. . * West, M. L. (2003), ''Greek Epic Fragments: From the Seventh to the Fifth Centuries BC''. Edited and translated by Martin L. West. Loeb Classical Library No. 497. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2003

Online version at Harvard University Press

* Whitbread, Leslie George

''Fulgentius the Mythographer''

Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1971. * Woodford, Susan, Spier, Jeffrey, "Kerberos", in ''

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

In

In Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities ...

, Cerberus (; grc-gre, Κέρβερος ''Kérberos'' ), often referred to as the hound of Hades, is a multi-headed dog that guards the gates of the Underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underwor ...

to prevent the dead from leaving. He was the offspring of the monsters Echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

and Typhon

Typhon (; grc, Τυφῶν, Typhôn, ), also Typhoeus (; grc, Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús, label=none), Typhaon ( grc, Τυφάων, Typháōn, label=none) or Typhos ( grc, Τυφώς, Typhṓs, label=none), was a monstrous serpentine giant an ...

, and was usually described as having three heads, a serpent for a tail, and snakes protruding from multiple parts of his body. Cerberus is primarily known for his capture by Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptiv ...

, the last of Heracles' twelve labours

The Labours of Hercules or Labours of Heracles ( grc-gre, wikt:ὁ, οἱ wikt:Ἡρακλῆς, Ἡρακλέους wikt:ἆθλος, ἆθλοι, ) are a series of episodes concerning a penance carried out by Heracles, the greatest of the ...

.

Descriptions

Descriptions of Cerberus vary, including the number of his heads. Cerberus was usually three-headed, though not always. Cerberus had several multi-headed relatives. His father was the multi snake-headedTyphon

Typhon (; grc, Τυφῶν, Typhôn, ), also Typhoeus (; grc, Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús, label=none), Typhaon ( grc, Τυφάων, Typháōn, label=none) or Typhos ( grc, Τυφώς, Typhṓs, label=none), was a monstrous serpentine giant an ...

, and Cerberus was the brother of three other multi-headed monsters, the multi-snake-headed Lernaean Hydra

The Lernaean Hydra or Hydra of Lerna ( grc-gre, Λερναῖα Ὕδρα, ''Lernaîa Hýdra''), more often known simply as the Hydra, is a snake, serpentine water monster in Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Its lair was the lake of Le ...

; Orthrus

In Greek mythology, Orthrus ( grc-gre, Ὄρθρος, ''Orthros'') or Orthus ( grc-gre, Ὄρθος, ''Orthos'') was, according to the mythographer Apollodorus, a two-headed dog who guarded Geryon's cattle and was killed by Heracles. He was the ...

, the two-headed dog who guarded the Cattle of Geryon; and the Chimera

Chimera, Chimaera, or Chimaira (Greek for " she-goat") originally referred to:

* Chimera (mythology), a fire-breathing monster of Ancient Lycia said to combine parts from multiple animals

* Mount Chimaera, a fire-spewing region of Lycia or Cilici ...

, who had three heads: that of a lion, a goat, and a snake. And, like these close relatives, Cerberus was, with only the rare iconographic exception, multi-headed.

In the earliest description of Cerberus, Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet ...

's ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contain ...

'' (c. 8th – 7th century BC), Cerberus has fifty heads, while Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar ...

(c. 522 – c. 443 BC) gave him one hundred heads. However, later writers almost universally give Cerberus three heads. An exception is the Latin poet Horace's Cerberus which has a single dog head, and one hundred snake heads. Perhaps trying to reconcile these competing traditions, Apollodorus's Cerberus has three dog heads and the heads of "all sorts of snakes" along his back, while the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

poet John Tzetzes (who probably based his account on Apollodorus) gives Cerberus fifty heads, three of which were dog heads, the rest being the "heads of other beasts of all sorts".

In art Cerberus is most commonly depicted with two dog heads (visible), never more than three, but occasionally with only one. On one of the two earliest depictions (c. 590–580 BC), a

In art Cerberus is most commonly depicted with two dog heads (visible), never more than three, but occasionally with only one. On one of the two earliest depictions (c. 590–580 BC), a Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

ian cup from Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

** Ancient Argos, the ancient city

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

(see below), now lost, Cerberus was shown as a normal single-headed dog. The first appearance of a three-headed Cerberus occurs on a mid-sixth-century BC Laconian cup (see below).

Horace's many snake-headed Cerberus followed a long tradition of Cerberus being part snake. This is perhaps already implied as early as in Hesiod's ''Theogony'', where Cerberus' mother is the half-snake Echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

, and his father the snake-headed Typhon. In art, Cerberus is often shown as being part snake, for example the lost Corinthian cup showed snakes protruding from Cerberus' body, while the mid sixth-century BC Laconian cup gives Cerberus a snake for a tail. In the literary record, the first certain indication of Cerberus' serpentine nature comes from the rationalized account of Hecataeus of Miletus (fl. 500–494 BC), who makes Cerberus a large poisonous snake. Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

refers to Cerberus' composite nature, and Euphorion of Chalcis

Euphorion of Chalcis ( el, Εὐφορίων ὁ Χαλκιδεύς) was a Greek poet and grammarian, born at Chalcis in Euboea about 275 BC.

Euphorion spent much of his life in Athens, where he amassed great wealth. After studying philosophy wit ...

(3rd century BC) describes Cerberus as having multiple snake tails, and presumably in connection to his serpentine nature, associates Cerberus with the creation of the poisonous aconite plant. Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

has snakes writhe around Cerberus' neck, Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's Cerberus has a venomous mouth, necks "vile with snakes", and "hair inwoven with the threatening snake", while Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

gives Cerberus a mane consisting of snakes, and a single snake tail.

Cerberus was given various other traits. According to Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars a ...

, Cerberus not only had three heads but three bodies, and according to Virgil he had multiple backs. Cerberus ate raw flesh (according to Hesiod), had eyes which flashed fire (according to Euphorion), a three-tongued mouth (according to Horace), and acute hearing (according to Seneca).

The Twelfth Labour of Heracles

Cerberus' only mythology concerns his capture by Heracles. As early as

Cerberus' only mythology concerns his capture by Heracles. As early as Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

we learn that Heracles was sent by Eurystheus

In Greek mythology, Eurystheus (; grc-gre, Εὐρυσθεύς, , broad strength, ) was king of Tiryns, one of three Mycenaean strongholds in the Argolid, although other authors including Homer and Euripides cast him as ruler of Argos.

Fami ...

, the king of Tiryns

Tiryns or (Ancient Greek: Τίρυνς; Modern Greek: Τίρυνθα) is a Mycenaean archaeological site in Argolis in the Peloponnese, and the location from which the mythical hero Heracles performed his Twelve Labours. It lies south of M ...

, to bring back Cerberus from Hades the king of the underworld. According to Apollodorus, this was the twelfth and final labour imposed on Heracles. In a fragment from a lost play ''Pirithous'', (attributed to either Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars a ...

or Critias

Critias (; grc-gre, Κριτίας, ''Kritias''; c. 460 – 403 BC) was an ancient Athenian political figure and author. Born in Athens, Critias was the son of Callaeschrus and a first cousin of Plato's mother Perictione. He became a leading ...

) Heracles says that, although Eurystheus commanded him to bring back Cerberus, it was not from any desire to see Cerberus, but only because Eurystheus thought that the task was impossible.

Heracles was aided in his mission by his being an initiate of the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries ( el, Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια, Eleusínia Mystḗria) were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece. They are th ...

. Euripides has his initiation being "lucky" for Heracles in capturing Cerberus. And both Diodorus Siculus and Apollodorus say that Heracles was initiated into the Mysteries, in preparation for his descent into the underworld. According to Diodorus, Heracles went to Athens, where Musaeus, the son of Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

, was in charge of the initiation rites, while according to Apollodorus, he went to Eumolpus

In Greek Mythology, Eumolpus (; Ancient Greek: Εὔμολπος ''Eúmolpos'', "good singer" or "sweet singing", derived from εὖ ''eu'' "good" and μολπή ''molpe'' "song", "singing") was a legendary king of Thrace. He was described as hav ...

at Eleusis.

Heracles also had the help of Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, wikt:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travelle ...

, the usual guide of the underworld, as well as Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded ...

. In the ''Odyssey'', Homer has Hermes and Athena as his guides. And Hermes and Athena are often shown with Heracles on vase paintings depicting Cerberus' capture. By most accounts, Heracles made his descent into the underworld through an entrance at Tainaron

Cape Matapan ( el, Κάβο Ματαπάς, Maniot dialect: Ματαπά), also named as Cape Tainaron or Taenarum ( el, Ακρωτήριον Ταίναρον), or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matapan ...

, the most famous of the various Greek entrances to the underworld. The place is first mentioned in connection with the Cerberus story in the rationalized account of Hecataeus of Miletus (fl. 500–494 BC), and Euripides, Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

, and Apolodorus, all have Heracles descend into the underworld there. However Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

reports that Heracles was said to have descended at the Acherusian Chersonese near Heraclea Pontica

__NOTOC__

Heraclea Pontica (; gr, Ἡράκλεια Ποντική, Hērakleia Pontikē), known in Byzantine and later times as Pontoheraclea ( gr, Ποντοηράκλεια, Pontohērakleia), was an ancient city on the coast of Bithynia in Asi ...

, on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, a place more usually associated with Heracles' exit from the underworld (see below). Heraclea, founded c. 560 BC, perhaps took its name from the association of its site with Heracles' Cerberian exploit.

Theseus and Pirithous

While in the underworld, Heracles met the heroesTheseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describ ...

and Pirithous

Pirithous (; grc-gre, Πειρίθοος or , derived from ; also transliterated as Perithous), in Greek mythology, was the King of the Lapiths of Larissa in Thessaly, as well as best friend to Theseus.

Biography

Pirithous was a son of "h ...

, where the two companions were being held prisoner by Hades for attempting to carry off Hades' wife Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone ( ; gr, Περσεφόνη, Persephónē), also called Kore or Cora ( ; gr, Κόρη, Kórē, the maiden), is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld after ...

. Along with bringing back Cerberus, Heracles also managed (usually) to rescue Theseus, and in some versions Pirithous as well. According to Apollodorus, Heracles found Theseus and Pirithous near the gates of Hades, bound to the "Chair of Forgetfulness, to which they grew and were held fast by coils of serpents", and when they saw Heracles, "they stretched out their hands as if they should be raised from the dead by his might", and Heracles was able to free Theseus, but when he tried to raise up Pirithous, "the earth quaked and he let go."

The earliest evidence for the involvement of Theseus and Pirithous in the Cerberus story, is found on a shield-band relief (c. 560 BC) from Olympia, where Theseus and Pirithous (named) are seated together on a chair, arms held out in supplication, while Heracles approaches, about to draw his sword. The earliest literary mention of the rescue occurs in Euripides, where Heracles saves Theseus (with no mention of Pirithous). In the lost play ''Pirithous'', both heroes are rescued, while in the rationalized account of Philochorus

Philochorus of Athens (; grc, Φιλόχορος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος; c. 340 BC – c. 261 BC), was a Greek historian and Atthidographer of the third century BC, and a member of a priestly family. He was a seer and interpreter of signs, and a ...

, Heracles was able to rescue Theseus, but not Pirithous. In one place Diodorus says Heracles brought back both Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describ ...

and Pirithous

Pirithous (; grc-gre, Πειρίθοος or , derived from ; also transliterated as Perithous), in Greek mythology, was the King of the Lapiths of Larissa in Thessaly, as well as best friend to Theseus.

Biography

Pirithous was a son of "h ...

, by the favor of Persephone, while in another he says that Pirithous remained in Hades, or according to "some writers of myth" that neither Theseus, nor Pirithous returned. Both are rescued in Hyginus.

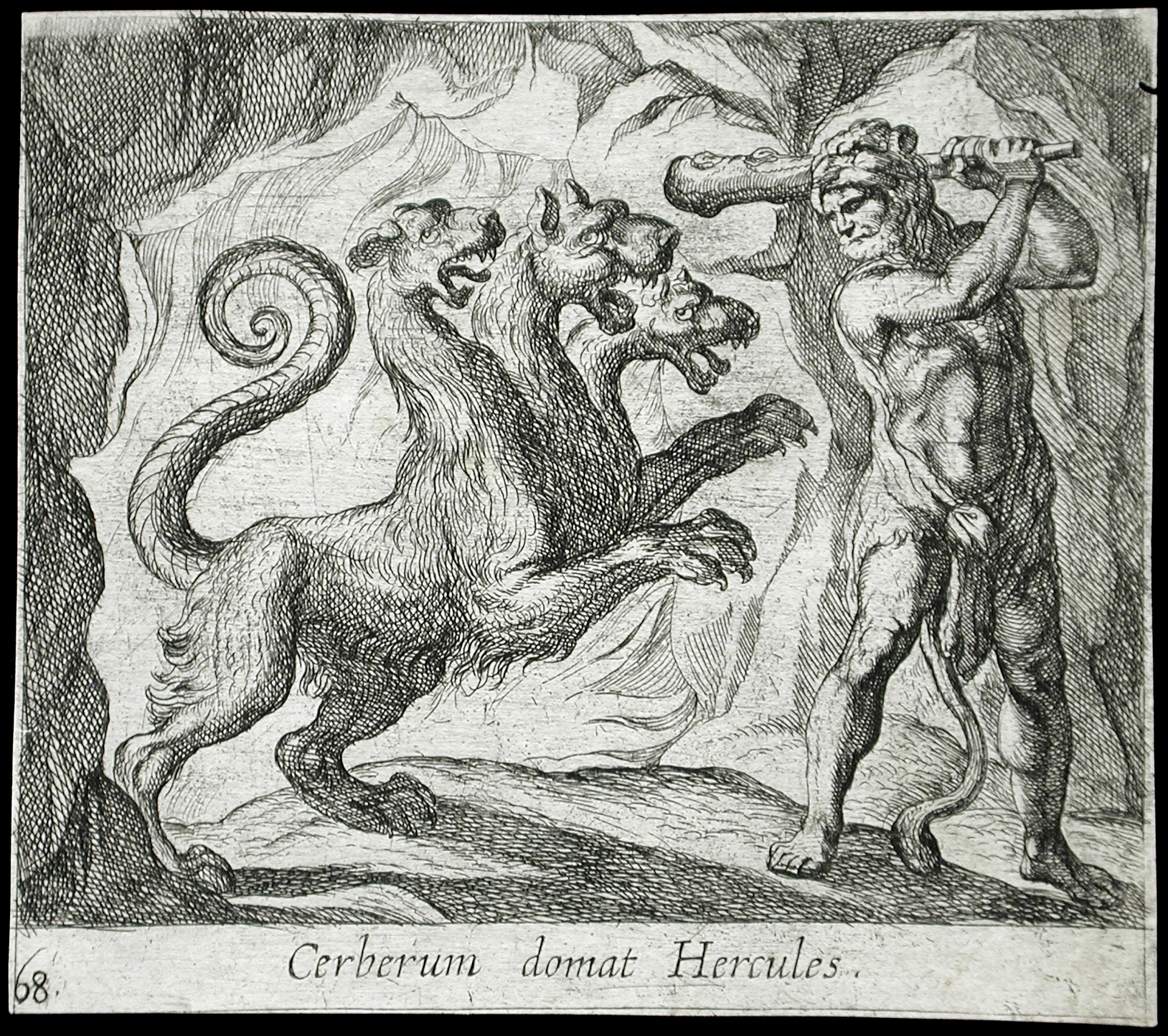

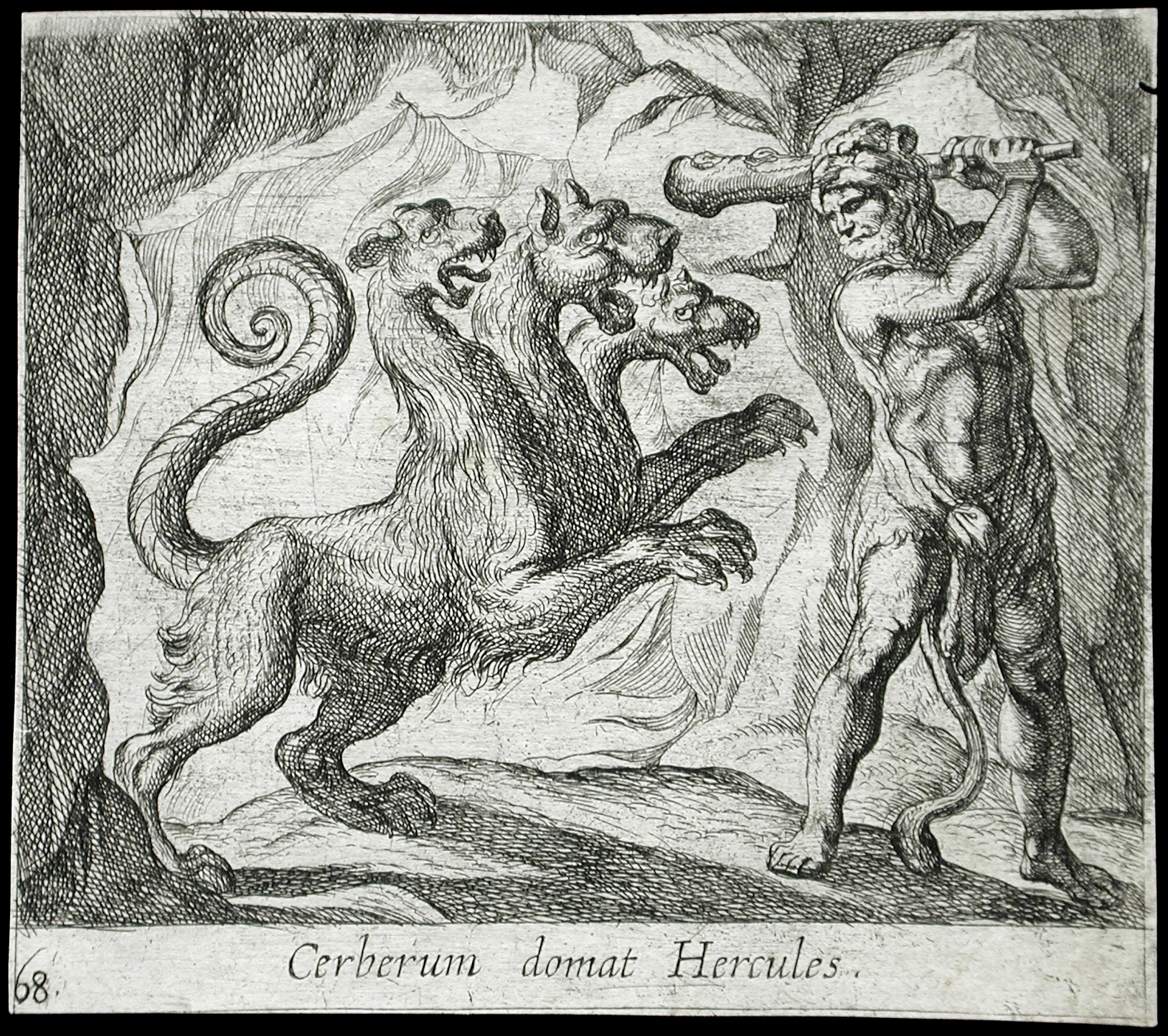

Capture

There are various versions of how Heracles accomplished Cerberus' capture. According to Apollodorus, Heracles asked Hades for Cerberus, and Hades told Heracles he would allow him to take Cerberus only if he "mastered him without the use of the weapons which he carried", and so, using his lion-skin as a shield, Heracles squeezed Cerberus around the head until he submitted.

In some early sources Cerberus' capture seems to involve Heracles fighting Hades. Homer (''Iliad'' 5.395–397) has Hades injured by an arrow shot by Heracles. A scholium to the ''Iliad'' passage, explains that Hades had commanded that Heracles "master Cerberus without shield or Iron". Heracles did this, by (as in Apollodorus) using his lion-skin instead of his shield, and making stone points for his arrows, but when Hades still opposed him, Heracles shot Hades in anger. Consistent with the no iron requirement, on an early-sixth-century BC lost Corinthian cup, Heracles is shown attacking Hades with a stone, while the iconographic tradition, from c. 560 BC, often shows Heracles using his wooden club against Cerberus.

Euripides has Amphitryon ask Heracles: "Did you conquer him in fight, or receive him from the goddess .e. Persephone To which Heracles answers: "In fight", and the ''Pirithous'' fragment says that Heracles "overcame the beast by force". However, according to Diodorus, Persephone welcomed Heracles "like a brother" and gave Cerberus "in chains" to Heracles. Aristophanes has Heracles seize Cerberus in a stranglehold and run off, while Seneca has Heracles again use his lion-skin as shield, and his wooden club, to subdue Cerberus, after which a quailing Hades and Persephone allow Heracles to lead a chained and submissive Cerberus away. Cerberus is often shown being chained, and Ovid tells that Heracles dragged the three headed Cerberus with chains of

There are various versions of how Heracles accomplished Cerberus' capture. According to Apollodorus, Heracles asked Hades for Cerberus, and Hades told Heracles he would allow him to take Cerberus only if he "mastered him without the use of the weapons which he carried", and so, using his lion-skin as a shield, Heracles squeezed Cerberus around the head until he submitted.

In some early sources Cerberus' capture seems to involve Heracles fighting Hades. Homer (''Iliad'' 5.395–397) has Hades injured by an arrow shot by Heracles. A scholium to the ''Iliad'' passage, explains that Hades had commanded that Heracles "master Cerberus without shield or Iron". Heracles did this, by (as in Apollodorus) using his lion-skin instead of his shield, and making stone points for his arrows, but when Hades still opposed him, Heracles shot Hades in anger. Consistent with the no iron requirement, on an early-sixth-century BC lost Corinthian cup, Heracles is shown attacking Hades with a stone, while the iconographic tradition, from c. 560 BC, often shows Heracles using his wooden club against Cerberus.

Euripides has Amphitryon ask Heracles: "Did you conquer him in fight, or receive him from the goddess .e. Persephone To which Heracles answers: "In fight", and the ''Pirithous'' fragment says that Heracles "overcame the beast by force". However, according to Diodorus, Persephone welcomed Heracles "like a brother" and gave Cerberus "in chains" to Heracles. Aristophanes has Heracles seize Cerberus in a stranglehold and run off, while Seneca has Heracles again use his lion-skin as shield, and his wooden club, to subdue Cerberus, after which a quailing Hades and Persephone allow Heracles to lead a chained and submissive Cerberus away. Cerberus is often shown being chained, and Ovid tells that Heracles dragged the three headed Cerberus with chains of adamant

Adamant in classical mythology is an archaic form of diamond. In fact, the English word ''diamond'' is ultimately derived from ''adamas'', via Late Latin and Old French . In ancient Greek (), genitive (), literally 'unconquerable, untameabl ...

.

Exit from the underworld

There were several locations which were said to be the place where Heracles brought up Cerberus from the underworld. The geographer Strabo (63/64 BC – c. AD 24) reports that "according to the myth writers" Cerberus was brought up at Tainaron, the same place where Euripides has Heracles enter the underworld. Seneca has Heracles enter and exit at Tainaron. Apollodorus, although he has Heracles enter at Tainaron, has him exit at

There were several locations which were said to be the place where Heracles brought up Cerberus from the underworld. The geographer Strabo (63/64 BC – c. AD 24) reports that "according to the myth writers" Cerberus was brought up at Tainaron, the same place where Euripides has Heracles enter the underworld. Seneca has Heracles enter and exit at Tainaron. Apollodorus, although he has Heracles enter at Tainaron, has him exit at Troezen

Troezen (; ancient Greek: Τροιζήν, modern Greek: Τροιζήνα ) is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern Peloponnese, Greece, on the Argolid Peninsula. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the muni ...

. The geographer Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

tells us that there was a temple at Troezen with "altars to the gods said to rule under the earth", where it was said that, in addition to Cerberus being "dragged" up by Heracles, Semele

Semele (; Ancient Greek: Σεμέλη ), in Greek mythology, was the youngest daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, and the mother of Dionysus by Zeus in one of his many origin myths.

Certain elements of the cult of Dionysus and Semele came from ...

was supposed to have been brought up out of the underworld by Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Roma ...

.

Another tradition had Cerberus brought up at Heraclea Pontica (the same place which Xenophon had earlier associated with Heracles' descent) and the cause of the poisonous plant aconite which grew there in abundance. Herodorus of Heraclea and Euphorion said that when Heracles brought Cerberus up from the underworld at Heraclea, Cerberus "vomited bile" from which the aconite plant grew up. Ovid, also makes Cerberus the cause of the poisonous aconite, saying that on the "shores of Scythia", upon leaving the underworld, as Cerberus was being dragged by Heracles from a cave, dazzled by the unaccustomed daylight, Cerberus spewed out a "poison-foam", which made the aconite plants growing there poisonous. Seneca's Cerberus too, like Ovid's, reacts violently to his first sight of daylight. Enraged, the previously submissive Cerberus struggles furiously, and Heracles and Theseus must together drag Cerberus into the light.

Pausanias reports that according to local legend Cerberus was brought up through a chasm in the earth dedicated to Clymenus (Hades) next to the sanctuary of Chthonia In Greek mythology, the name Chthonia (Ancient Greek: Χθωνία means 'of the earth') may refer to:

*Chthonia, an Athenian princess and the youngest daughter of King Erechtheus and Praxithea, daughter of Phrasimus and Diogeneia. She was sacrific ...

at Hermione

Hermione may refer to:

People

* Hermione (given name), a female given name

* Hermione (mythology), only daughter of Menelaus and Helen in Greek mythology and original bearer of the name

Arts and literature

* ''Cadmus et Hermione'', an opera by ...

, and in Euripides' ''Heracles'', though Euripides does not say that Cerberus was brought out there, he has Cerberus kept for a while in the "grove of Chthonia In Greek mythology, the name Chthonia (Ancient Greek: Χθωνία means 'of the earth') may refer to:

*Chthonia, an Athenian princess and the youngest daughter of King Erechtheus and Praxithea, daughter of Phrasimus and Diogeneia. She was sacrific ...

" at Hermione. Pausanias also mentions that at Mount Laphystion in Boeotia, that there was a statue of Heracles Charops ("with bright eyes"), where the Boeotians said Heracles brought up Cerberus. Other locations which perhaps were also associated with Cerberus being brought out of the underworld include, Hierapolis, Thesprotia

Thesprotia (; el, Θεσπρωτία, ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the Epirus region. Its capital and largest town is Igoumenitsa. Thesprotia is named after the Thesprotians, an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the ...

, and Emeia near Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. ...

.

Presented to Eurystheus, returned to Hades

In some accounts, after bringing Cerberus up from the underworld, Heracles paraded the captured Cerberus through Greece. Euphorion has Heracles lead Cerberus through Midea inArgolis

Argolis or Argolida ( el, Αργολίδα , ; , in ancient Greek and Katharevousa) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Peloponnese, situated in the eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula and part of the ...

, as women and children watch in fear, and Diodorus Siculus says of Cerberus, that Heracles "carried him away to the amazement of all and exhibited him to men." Seneca has Juno complain of Heracles "highhandedly parading the black hound through Argive cities" and Heracles greeted by laurel-wreathed crowds, "singing" his praises.

Then, according to Apollodorus, Heracles showed Cerberus to Eurystheus, as commanded, after which he returned Cerberus to the underworld. However, according to Hesychius of Alexandria

Hesychius of Alexandria ( grc, Ἡσύχιος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς, Hēsýchios ho Alexandreús, lit=Hesychios the Alexandrian) was a Greek grammarian who, probably in the 5th or 6th century AD,E. Dickey, Ancient Greek Scholarship (2007 ...

, Cerberus escaped, presumably returning to the underworld on his own.

Principal sources

The earliest mentions of Cerberus (c. 8th – 7th century BC) occur in

The earliest mentions of Cerberus (c. 8th – 7th century BC) occur in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' and ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'', and Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet ...

's ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contain ...

''. Homer does not name or describe Cerberus, but simply refers to Heracles being sent by Eurystheus

In Greek mythology, Eurystheus (; grc-gre, Εὐρυσθεύς, , broad strength, ) was king of Tiryns, one of three Mycenaean strongholds in the Argolid, although other authors including Homer and Euripides cast him as ruler of Argos.

Fami ...

to fetch the "hound of Hades", with Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, wikt:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travelle ...

and Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded ...

as his guides, and, in a possible reference to Cerberus' capture, that Heracles shot Hades with an arrow. According to Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet ...

, Cerberus was the offspring of the monsters Echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

and Typhon

Typhon (; grc, Τυφῶν, Typhôn, ), also Typhoeus (; grc, Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús, label=none), Typhaon ( grc, Τυφάων, Typháōn, label=none) or Typhos ( grc, Τυφώς, Typhṓs, label=none), was a monstrous serpentine giant an ...

, was fifty-headed, ate raw flesh, and was the "brazen-voiced hound of Hades", who fawns on those that enter the house of Hades, but eats those who try to leave.

Stesichorus

Stesichorus (; grc-gre, Στησίχορος, ''Stēsichoros''; c. 630 – 555 BC) was a Greek lyric poet native of today's Calabria (Southern Italy). He is best known for telling epic stories in lyric metres, and for some ancient traditions abo ...

(c. 630 – 555 BC) apparently wrote a poem called ''Cerberus'', of which virtually nothing remains. However the early-sixth-century BC-lost Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

ian cup from Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

** Ancient Argos, the ancient city

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

, which showed a single head, and snakes growing out from many places on his body, was possibly influenced by Stesichorus' poem. The mid-sixth-century BC cup from Laconia gives Cerberus three heads and a snake tail, which eventually becomes the standard representation.

Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar ...

(c. 522 – c. 443 BC) apparently gave Cerberus one hundred heads. Bacchylides

Bacchylides (; grc-gre, Βακχυλίδης; – ) was a Greek lyric poet. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets, which included his uncle Simonides. The elegance and polished style of his lyrics have been noted ...

(5th century BC) also mentions Heracles bringing Cerberus up from the underworld, with no further details. Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

(c. 495 – c. 405 BC), in his ''Women of Trachis

''Women of Trachis'' or ''The Trachiniae'' ( grc, Τραχίνιαι, ) c. 450–425 BC, is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles.

''Women of Trachis'' is generally considered to be less developed than Sophocles' other works, and its dating has been ...

'', makes Cerberus three-headed, and in his ''Oedipus at Colonus

''Oedipus at Colonus'' (also ''Oedipus Coloneus''; grc, Οἰδίπους ἐπὶ Κολωνῷ, ''Oidipous epi Kolōnōi'') is the last of the three Theban plays of the Athenian tragedian Sophocles. It was written shortly before Sophocles's ...

'', the Chorus asks that Oedipus be allowed to pass the gates of the underworld undisturbed by Cerberus, called here the "untamable Watcher of Hades". Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars a ...

(c. 480 – 406 BC) describes Cerberus as three-headed, and three-bodied, says that Heracles entered the underworld at Tainaron, has Heracles say that Cerberus was not given to him by Persephone, but rather he fought and conquered Cerberus, "for I had been lucky enough to witness the rites of the initiated", an apparent reference to his initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries ( el, Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια, Eleusínia Mystḗria) were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece. They are th ...

, and says that the capture of Cerberus was the last of Heracles' labors. The lost play ''Pirthous'' (attributed to either Euripides or his late contemporary Critias

Critias (; grc-gre, Κριτίας, ''Kritias''; c. 460 – 403 BC) was an ancient Athenian political figure and author. Born in Athens, Critias was the son of Callaeschrus and a first cousin of Plato's mother Perictione. He became a leading ...

) has Heracles say that he came to the underworld at the command of Eurystheus, who had ordered him to bring back Cerberus alive, not because he wanted to see Cerberus, but only because Eurystheus thought Heracles would not be able to accomplish the task, and that Heracles "overcame the beast" and "received favour from the gods".

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

(c. 425 – 348 BC) refers to Cerberus' composite nature, citing Cerberus, along with Scylla and the Chimera, as an example from "ancient fables" of a creature composed of many animal forms "grown together in one". Euphorion of Chalcis

Euphorion of Chalcis ( el, Εὐφορίων ὁ Χαλκιδεύς) was a Greek poet and grammarian, born at Chalcis in Euboea about 275 BC.

Euphorion spent much of his life in Athens, where he amassed great wealth. After studying philosophy wit ...

(3rd century BC) describes Cerberus as having multiple snake tails, and eyes that flashed, like sparks from a blacksmith's forge, or the volcaninc Mount Etna. From Euphorion, also comes the first mention of a story which told that at Heraclea Pontica

__NOTOC__

Heraclea Pontica (; gr, Ἡράκλεια Ποντική, Hērakleia Pontikē), known in Byzantine and later times as Pontoheraclea ( gr, Ποντοηράκλεια, Pontohērakleia), was an ancient city on the coast of Bithynia in Asi ...

, where Cerberus was brought out of the underworld, by Heracles, Cerberus "vomited bile" from which the poisonous aconite plant grew up.

According to Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC), the capture of Cerberus was the eleventh of Heracles' labors, the twelfth and last being stealing the Apples of the Hesperides

In Greek mythology, the Hesperides (; , ) are the nymphs of evening and golden light of sunsets, who were the "Daughters of the Evening" or "Nymphs of the West". They were also called the Atlantides () from their reputed father, the Titan Atla ...

. Diodorus says that Heracles thought it best to first go to Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

to take part in the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries ( el, Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια, Eleusínia Mystḗria) were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece. They are th ...

, " Musaeus, the son of Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

, being at that time in charge of the initiatory rites", after which, he entered into the underworld "welcomed like a brother by Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone ( ; gr, Περσεφόνη, Persephónē), also called Kore or Cora ( ; gr, Κόρη, Kórē, the maiden), is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld after ...

", and "receiving the dog Cerberus in chains he carried him away to the amazement of all and exhibited him to men."

In Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of th ...

'' (1st century BC), Aeneas

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas (, ; from ) was a Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite (equivalent to the Roman Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons ...

and the Sibyl

The sibyls (, singular ) were prophetesses or oracles in Ancient Greece.

The sibyls prophesied at holy sites.

A sibyl at Delphi has been dated to as early as the eleventh century BC by PausaniasPausanias 10.12.1 when he described local tradi ...

encounter Cerberus in a cave, where he "lay at vast length", filling the cave "from end to end", blocking the entrance to the underworld. Cerberus is described as "triple-throated", with "three fierce mouths", multiple "large backs", and serpents writhing around his neck. The Sibyl throws Cerberus a loaf laced with honey and herbs to induce sleep, enabling Aeneas

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas (, ; from ) was a Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite (equivalent to the Roman Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons ...

to enter the underworld, and so apparently for Virgil—contradicting Hesiod—Cerberus guarded the underworld against entrance. Later Virgil describes Cerberus, in his bloody cave, crouching over half-gnawed bones. In his ''Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

'', Virgil refers to Cerberus, his "triple jaws agape" being tamed by Orpheus' playing his lyre.

Horace (65 – 8 BC) also refers to Cerberus yielding to Orphesus' lyre, here Cerberus has a single dog head, which "like a Fury's is fortified by a hundred snakes", with a "triple-tongued mouth" oozing "fetid breath and gore".

Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

(43 BC – AD 17/18) has Cerberus' mouth produce venom, and like Euphorion, makes Cerberus the cause of the poisonous plant aconite. According to Ovid, Heracles dragged Cerberus from the underworld, emerging from a cave "where 'tis fabled, the plant grew / on soil infected by Cerberian teeth", and dazzled by the daylight, Cerberus spewed out a "poison-foam", which made the aconite plants growing there poisonous.

Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

, in his tragedy ''Hercules Furens'' gives a detailed description of Cerberus and his capture.

Seneca's Cerberus has three heads, a mane of snakes, and a snake tail, with his three heads being covered in gore, and licked by the many snakes which surround them, and with hearing so acute that he can hear "even ghosts". Seneca has Heracles use his lion-skin as shield, and his wooden club, to beat Cerberus into submission, after which Hades and Persephone, quailing on their thrones, let Heracles lead a chained and submissive Cerberus away. But upon leaving the underworld, at his first sight of daylight, a frightened Cerberus struggles furiously, and Heracles, with the help of Theseus (who had been held captive by Hades, but released, at Heracles' request) drag Cerberus into the light. Seneca, like Diodorus, has Heracles parade the captured Cerberus through Greece.

Apollodorus' Cerberus has three dog-heads, a serpent for a tail, and the heads of many snakes on his back. According to Apollodorus, Heracles' twelfth and final labor was to bring back Cerberus from Hades. Heracles first went to Eumolpus

In Greek Mythology, Eumolpus (; Ancient Greek: Εὔμολπος ''Eúmolpos'', "good singer" or "sweet singing", derived from εὖ ''eu'' "good" and μολπή ''molpe'' "song", "singing") was a legendary king of Thrace. He was described as hav ...

to be initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries ( el, Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια, Eleusínia Mystḗria) were initiations held every year for the cult of Demeter and Persephone based at the Panhellenic Sanctuary of Elefsina in ancient Greece. They are th ...

. Upon his entering the underworld, all the dead flee Heracles except for Meleager

In Greek mythology, Meleager (, grc-gre, Μελέαγρος, Meléagros) was a hero venerated in his ''temenos'' at Calydon in Aetolia. He was already famed as the host of the Calydonian boar hunt in the epic tradition that was reworked by Ho ...

and the Gorgon

A Gorgon ( /ˈɡɔːrɡən/; plural: Gorgons, Ancient Greek: Γοργών/Γοργώ ''Gorgṓn/Gorgṓ'') is a creature in Greek mythology. Gorgons occur in the earliest examples of Greek literature. While descriptions of Gorgons vary, the te ...

Medusa

In Greek mythology, Medusa (; Ancient Greek: Μέδουσα "guardian, protectress"), also called Gorgo, was one of the three monstrous Gorgons, generally described as winged human females with living venomous snakes in place of hair. Those ...

. Heracles drew his sword against Medusa, but Hermes told Heracles that the dead are mere "empty phantoms". Heracles asked Hades (here called Pluto) for Cerberus, and Hades said that Heracles could take Cerberus provided he was able to subdue him without using weapons. Heracles found Cerberus at the gates of Acheron

The Acheron (; grc, Ἀχέρων ''Acheron'' or Ἀχερούσιος ''Acherousios''; ell, Αχέροντας ''Acherontas'') is a river located in the Epirus region of northwest Greece. It is long, and its drainage area is . Its source is ...

, and with his arms around Cerberus, though being bitten by Cerberus' serpent tail, Heracles squeezed until Cerberus submitted. Heracles carried Cerberus away, showed him to Eurystheus, then returned Cerberus to the underworld.

In an apparently unique version of the story, related by the sixth-century AD Pseudo-Nonnus, Heracles descended into Hades to abduct Persephone, and killed Cerberus on his way back up.

Iconography

Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

ian cup (c. 590–580 BC) from Argos (now lost), shows a naked Heracles, with quiver on his back and bow in his right hand, striding left, accompanied by Hermes. Heracles threatens Hades with a stone, who flees left, while a goddess, perhaps Persephone or possibly Athena, standing in front of Hades' throne, prevents the attack. Cerberus, with a single canine head and snakes rising from his head and body, flees right. On the far right a column indicates the entrance to Hades' palace. Many of the elements of this scene—Hermes, Athena, Hades, Persephone, and a column or portico—are common occurrences in later works. The other earliest depiction, a relief '' pithos'' fragment from Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

(c. 590–570 BC), is thought to show a single lion-headed Cerberus with a snake (open-mouthed) over his back being led to the right.

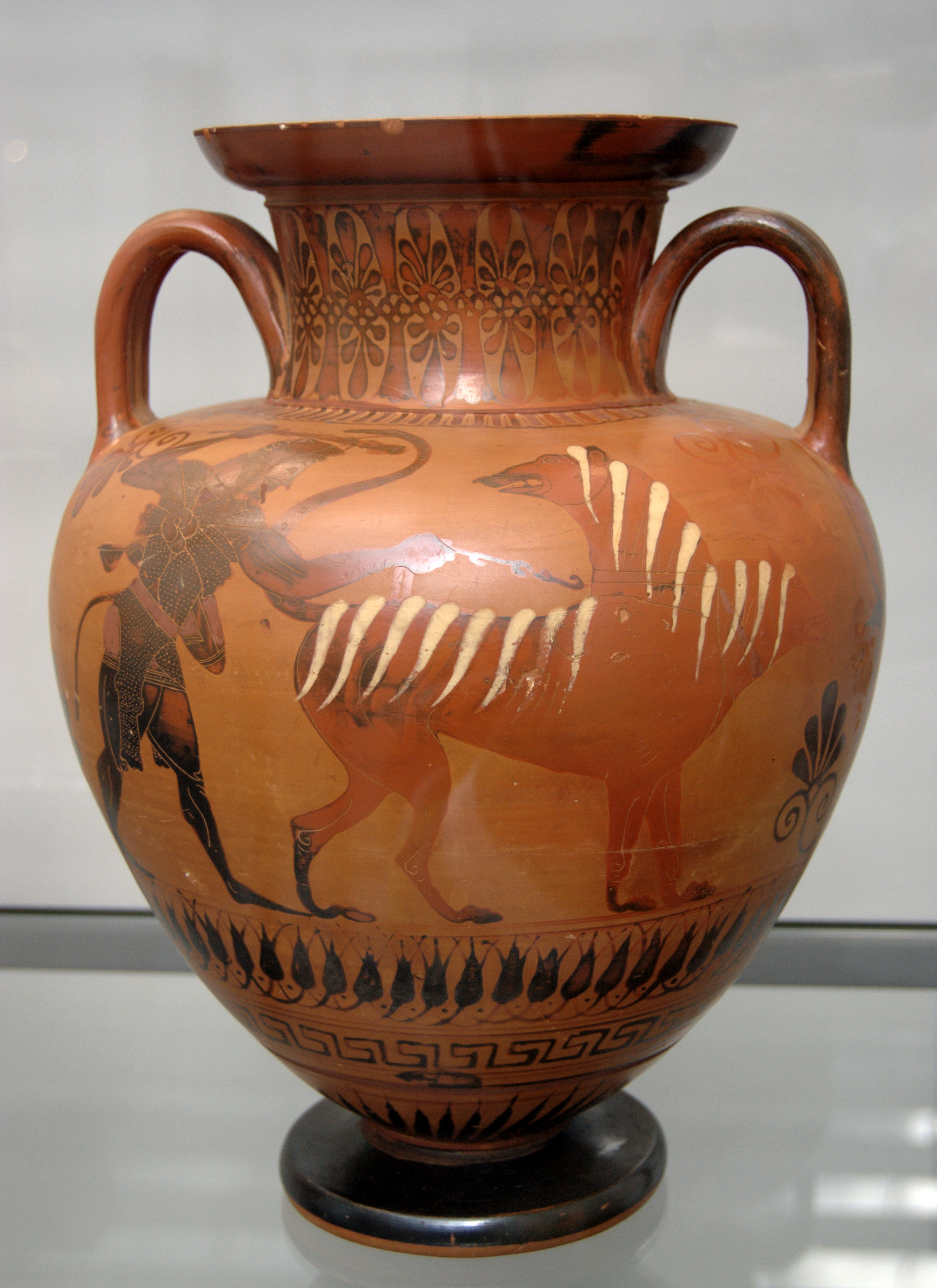

A mid-sixth-century BC Laconian cup by the Hunt Painter adds several new features to the scene which also become common in later works: three heads, a snake tail, Cerberus' chain and Heracles' club. Here Cerberus has three canine heads, is covered by a shaggy coat of snakes, and has a tail which ends in a snake head. He is being held on a chain leash by Heracles who holds his club raised over head.

In Greek art, the vast majority of depictions of Heracles and Cerberus occur on Attic vases. Although the lost Corinthian cup shows Cerberus with a single dog head, and the relief ''pithos'' fragment (c. 590–570 BC) apparently shows a single lion-headed Cerberus, in Attic vase painting Cerberus usually has two dog heads. In other art, as in the Laconian cup, Cerberus is usually three-headed. Occasionally in Roman art Cerberus is shown with a large central lion head and two smaller dog heads on either side.

As in the Corinthian and Laconian cups (and possibly the relief ''pithos'' fragment), Cerberus is often depicted as part snake. In Attic vase painting, Cerberus is usually shown with a snake for a tail or a tail which ends in the head of a snake. Snakes are also often shown rising from various parts of his body including snout, head, neck, back, ankles, and paws.

Two Attic amphoras from Vulci, one (c. 530–515 BC) by the Bucci Painter (Munich 1493), the other (c. 525–510 BC) by the Andokides painter (Louvre F204), in addition to the usual two heads and snake tail, show Cerberus with a mane down his necks and back, another typical Cerberian feature of Attic vase painting. Andokides' amphora also has a small snake curling up from each of Cerberus' two heads.

Besides this lion-like mane and the occasional lion-head mentioned above, Cerberus was sometimes shown with other leonine features. A pitcher (c. 530–500) shows Cerberus with mane and claws, while a first-century BC

As in the Corinthian and Laconian cups (and possibly the relief ''pithos'' fragment), Cerberus is often depicted as part snake. In Attic vase painting, Cerberus is usually shown with a snake for a tail or a tail which ends in the head of a snake. Snakes are also often shown rising from various parts of his body including snout, head, neck, back, ankles, and paws.

Two Attic amphoras from Vulci, one (c. 530–515 BC) by the Bucci Painter (Munich 1493), the other (c. 525–510 BC) by the Andokides painter (Louvre F204), in addition to the usual two heads and snake tail, show Cerberus with a mane down his necks and back, another typical Cerberian feature of Attic vase painting. Andokides' amphora also has a small snake curling up from each of Cerberus' two heads.

Besides this lion-like mane and the occasional lion-head mentioned above, Cerberus was sometimes shown with other leonine features. A pitcher (c. 530–500) shows Cerberus with mane and claws, while a first-century BC sardonyx

Onyx primarily refers to the parallel banded variety of chalcedony, a silicate mineral. Agate and onyx are both varieties of layered chalcedony that differ only in the form of the bands: agate has curved bands and onyx has parallel bands. The c ...

cameo shows Cerberus with leonine body and paws. In addition, a limestone relief fragment from Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

(c. 320–300 BC) shows Cerberus with three lion-like heads.

During the second quarter of the 5th century BC the capture of Cerberus disappears from Attic vase painting. After the early third century BC, the subject becomes rare everywhere until the Roman period. In Roman art the capture of Cerberus is usually shown together with other labors. Heracles and Cerberus are usually alone, with Heracles leading Cerberus.

Etymology

The etymology of Cerberus' name is uncertain. Ogden refers to attempts to establish an Indo-European etymology as "not yet successful". It has been claimed to be related to the

The etymology of Cerberus' name is uncertain. Ogden refers to attempts to establish an Indo-European etymology as "not yet successful". It has been claimed to be related to the Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

word सर्वरा ''sarvarā'', used as an epithet of one of the dogs of Yama

Yama (Devanagari: यम) or Yamarāja (यमराज), is a deity of death, dharma, the south direction, and the underworld who predominantly features in Hindu and Buddhist religion, belonging to an early stratum of Rigvedic Hindu deities. ...

, from a Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo- ...

word *''k̑érberos'', meaning "spotted". Lincoln (1991), among others, critiques this etymology. This etymology was also rejected by Manfred Mayrhofer

Manfred Mayrhofer (26 September 1926 – 31 October 2011) was an Austrian Indo-Europeanist who specialized in Indo-Iranian languages. Mayrhofer served as professor emeritus at the University of Vienna. He is noted for his etymological dictionar ...

, who proposed an Austro-Asiatic origin for the word, and Beekes. Lincoln notes a similarity between Cerberus and the Norse mythological dog Garmr

In Norse mythology, Garmr or Garm (Old Norse: ; "rag") is a wolf or dog associated with both Hel and Ragnarök, and described as a blood-stained guardian of Hel's gate.

Name

The Old Norse name ''Garmr'' has been interpreted as meaning "rag." ...

, relating both names to a Proto-Indo-European root ''*ger-'' "to growl" (perhaps with the suffixes ''-*m/*b'' and ''-*r''). However, as Ogden observes, this analysis actually requires ''Kerberos'' and ''Garmr'' to be derived from two ''different'' Indo-European roots (*''ker-'' and *''gher-'' respectively), and so does not actually establish a relationship between the two names.

Though probably not Greek, Greek etymologies for Cerberus have been offered. An etymology given by Servius (the late-fourth-century commentator on Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

)—but rejected by Ogden—derives Cerberus from the Greek word ''creoboros'' meaning "flesh-devouring". Another suggested etymology derives Cerberus from "Ker berethrou", meaning "evil of the pit".

Cerberus rationalized

At least as early as the 6th century BC, some ancient writers attempted to explain away various fantastical features of Greek mythology; included in these are various rationalized accounts of the Cerberus story. The earliest such account (late 6th century BC) is that of Hecataeus of Miletus. In his account Cerberus was not a dog at all, but rather simply a large venomous snake, which lived onTainaron

Cape Matapan ( el, Κάβο Ματαπάς, Maniot dialect: Ματαπά), also named as Cape Tainaron or Taenarum ( el, Ακρωτήριον Ταίναρον), or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matapan ...

. The serpent was called the "hound of Hades" only because anyone bitten by it died immediately, and it was this snake that Heracles brought to Eurystheus. The geographer Pausanias (who preserves for us Hecataeus' version of the story) points out that, since Homer does not describe Cerberus, Hecataeus' account does not necessarily conflict with Homer, since Homer's "Hound of Hades" may not in fact refer to an actual dog.

Other rationalized accounts make Cerberus out to be a normal dog. According to Palaephatus

Palaephatus (Ancient Greek: ) was the author of a rationalizing text on Greek mythology, the paradoxographical work ''On Incredible Things'' (; ), which survives in a (probably corrupt) Byzantine edition.

This work consists of an introduction and ...

(4th century BC) Cerberus was one of the two dogs who guarded the cattle of Geryon, the other being Orthrus

In Greek mythology, Orthrus ( grc-gre, Ὄρθρος, ''Orthros'') or Orthus ( grc-gre, Ὄρθος, ''Orthos'') was, according to the mythographer Apollodorus, a two-headed dog who guarded Geryon's cattle and was killed by Heracles. He was the ...

. Geryon lived in a city named Tricranium (in Greek ''Tricarenia'', "Three-Heads"), from which name both Cerberus and Geryon came to be called "three-headed". Heracles killed Orthus, and drove away Geryon's cattle, with Cerberus following along behind. Molossus, a Mycenaen, offered to buy Cerberus from Eurystheus (presumably having received the dog, along with the cattle, from Heracles). But when Eurystheus refused, Molossus stole the dog and penned him up in a cave in Tainaron. Eurystheus commanded Heracles to find Cerberus and bring him back. After searching the entire Peloponnesus, Heracles found where it was said Cerberus was being held, went down into the cave, and brought up Cerberus, after which it was said: "Heracles descended through the cave into Hades and brought up Cerberus."

In the rationalized account of Philochorus

Philochorus of Athens (; grc, Φιλόχορος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος; c. 340 BC – c. 261 BC), was a Greek historian and Atthidographer of the third century BC, and a member of a priestly family. He was a seer and interpreter of signs, and a ...

, in which Heracles rescues Theseus, Perithous is eaten by Cerberus. In this version of the story, Aidoneus (i.e., "Hades") is the mortal king of the Molossians

The Molossians () were a group of ancient Greek tribes which inhabited the region of Epirus in classical antiquity. Together with the Chaonians and the Thesprotians, they formed the main tribal groupings of the northwestern Greek group. On t ...

, with a wife named Persephone, a daughter named Kore (another name for the goddess Persephone) and a large mortal dog named Cerberus, with whom all suitors of his daughter were required to fight. After having stolen Helen, to be Theseus' wife, Theseus and Perithous, attempt to abduct Kore, for Perithous, but Aidoneus catches the two heroes, imprisons Theseus, and feeds Perithous to Cerberus. Later, while a guest of Aidoneus, Heracles asks Aidoneus to release Theseus, as a favor, which Aidoneus grants.

A 2nd-century AD Greek known as Heraclitus the paradoxographer Heraclitus Paradoxographus ( el, Ἡράκλειτος) is the author of the lesser-known of two works known as ''Peri Apiston'' (''On Unbelievable Tales''). Palaephatus was the author of a better-known work of paradoxography with the same title, m ...

(not to be confused with the 5th-century BC Greek philosopher Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrot ...

)—claimed that Cerberus had two pups that were never away from their father, which made Cerberus appear to be three-headed.

Cerberus allegorized

Servius, a medieval commentator on

Servius, a medieval commentator on Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of th ...

'', derived Cerberus' name from the Greek word ''creoboros'' meaning "flesh-devouring" (see above), and held that Cerberus symbolized the corpse-consuming earth, with Heracles' triumph over Cerberus representing his victory over earthly desires. Later, the mythographer Fulgentius Fulgentius is a Latin male given name which means "bright, brilliant". It may refer to:

* Fabius Planciades Fulgentius (5th–6th century), Latin grammarian

*Saint Fulgentius of Ruspe (5th–6th century), bishop of Ruspe, North Africa, possi ...

, allegorizes Cerberus' three heads as representing the three origins of human strife: "nature, cause, and accident", and (drawing on the same flesh-devouring etymology as Servius) as symbolizing "the three ages—infancy, youth, old age, at which death enters the world." The Byzantine historian and bishop Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

wrote that Cerberus was represented with three heads, because the positions of the sun above the earth are three—rising, midday, and setting.

The later Vatican Mythographers The so-called Vatican Mythographers ( la, Mythographi Vaticani) are the anonymous authors of three Latin mythographical texts found together in a single medieval manuscript, Vatican Reg. lat. 1401. The name is that used by Angelo Mai when he publi ...

repeat and expand upon the traditions of Servius and Fulgentius. All three Vatican Mythographers repeat Servius' derivation of Cerberus' name from ''creoboros''. The Second Vatican Mythographer repeats (nearly word for word) what Fulgentius had to say about Cerberus, while the Third Vatican Mythographer, in another very similar passage to Fugentius', says (more specifically than Fugentius), that for "the philosophers" Cerberus represented hatred, his three heads symbolizing the three kinds of human hatred: natural, causal, and casual (i.e. accidental).

The Second and Third Vatican Mythographers, note that the three brothers Zeus, Poseidon and Hades each have tripartite insignia, associating Hades' three-headed Cerberus, with Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek reli ...

' three-forked thunderbolt, and Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ...

's three-pronged trident, while the Third Vatican Mythographer adds that "some philosophers think of Cerberus as the tripartite earth: Asia, Africa, and Europe. This earth, swallowing up bodies, sends souls to Tartarus."

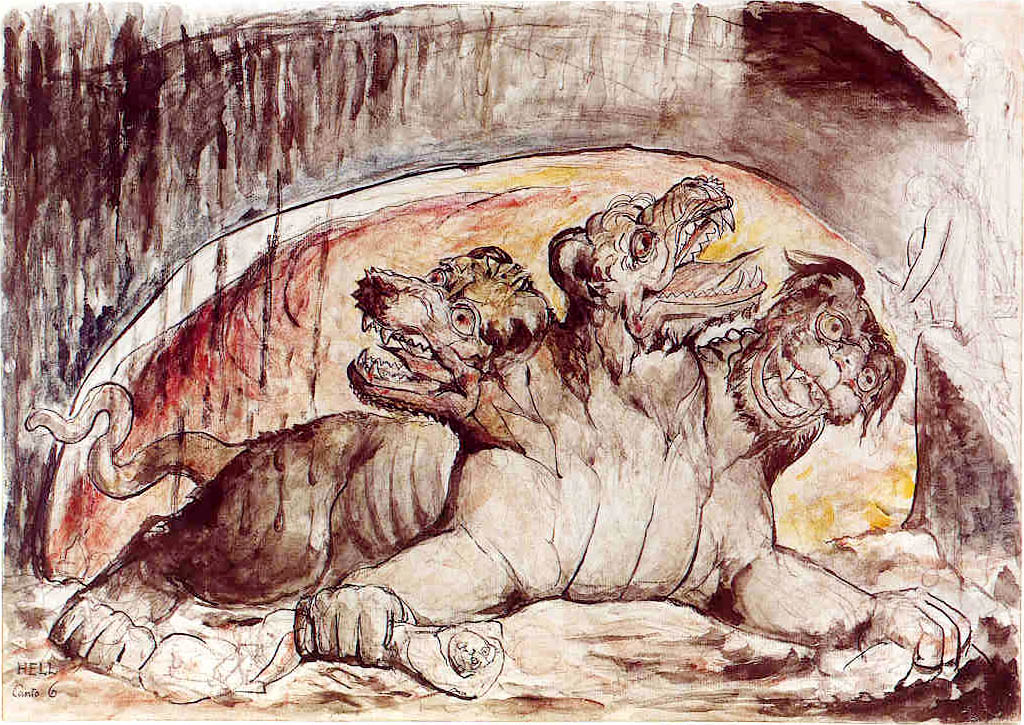

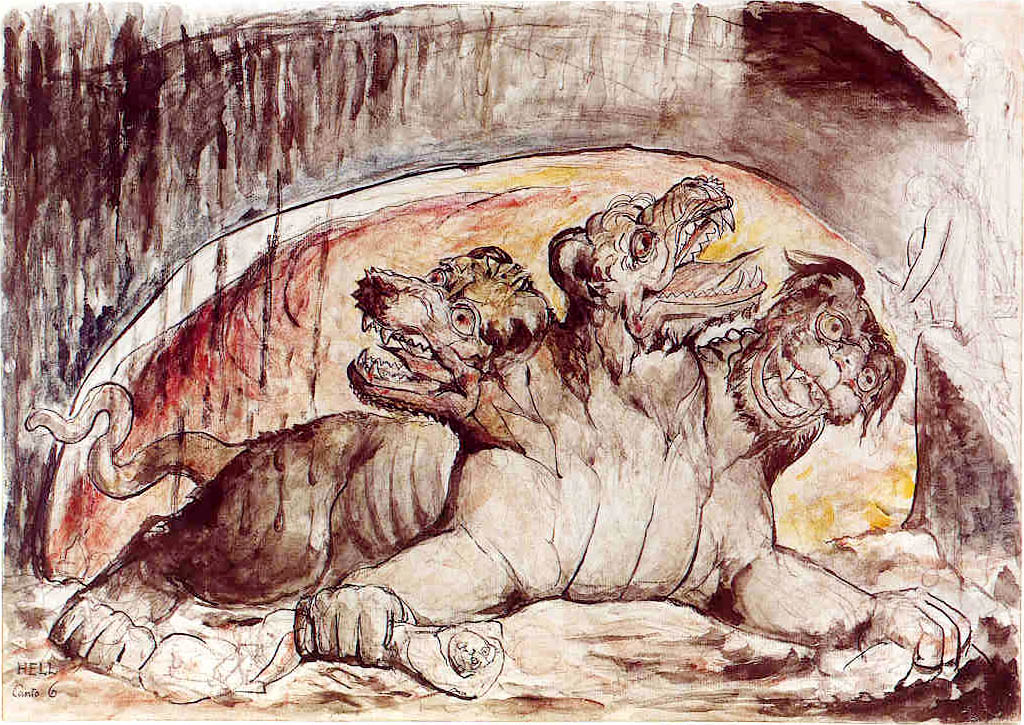

Virgil described Cerberus as "ravenous" (''fame rabida''), and a rapacious Cerberus became proverbial. Thus Cerberus came to symbolize avarice, and so, for example, in Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian people, Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', origin ...

's ''Inferno

Inferno may refer to:

* Hell, an afterlife place of suffering

* Conflagration, a large uncontrolled fire

Film

* ''L'Inferno'', a 1911 Italian film

* Inferno (1953 film), ''Inferno'' (1953 film), a film noir by Roy Ward Baker

* Inferno (1973 fi ...

,'' Cerberus is placed in the Third Circle of Hell, guarding over the gluttons, where he "rends the spirits, flays and quarters them," and Dante (perhaps echoing Servius' association of Cerbeus with earth) has his guide Virgil take up handfuls of earth and throw them into Cerberus' "rapacious gullets."

Constellation

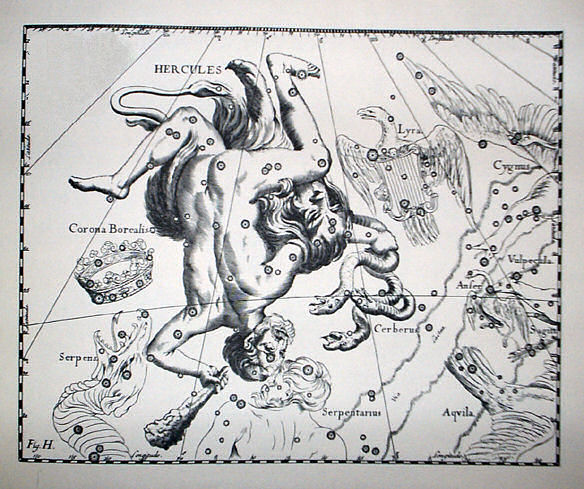

In the constellation Cerberus introduced by

In the constellation Cerberus introduced by Johannes Hevelius

Johannes Hevelius

Some sources refer to Hevelius as Polish:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Some sources refer to Hevelius as German:

*

*

*

*

*of the Royal Society

* (in German also known as ''Hevel''; pl, Jan Heweliusz; – 28 January 1687) was a councillor ...