Carcharodontosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Carcharodontosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of large carcharodontosaurid

The following cladogram after Apesteguía ''et al.'', 2016, shows the placement of ''Carcharodontosaurus'' within Carcharodontosauridae.

The following cladogram after Apesteguía ''et al.'', 2016, shows the placement of ''Carcharodontosaurus'' within Carcharodontosauridae.

Student Identifies Enormous New Dinosaur December 7 2007 from the Science daily

{{Taxonbar, from=Q14431 Carcharodontosaurids Late Cretaceous dinosaurs of Africa Cenomanian genus extinctions Bahariya Formation Fossil taxa described in 1931 Taxa named by Ernst Stromer Apex predators Cenomanian life

theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

that existed during the Cenomanian

The Cenomanian is, in the ICS' geological timescale, the oldest or earliest age of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or the lowest stage of the Upper Cretaceous Series. An age is a unit of geochronology; it is a unit of time; the stage is a unit in ...

age of the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

in Northern Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

. The genus ''Carcharodontosaurus'' is named after the shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

genus '' Carcharodon'', itself composed of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(, meaning "jagged" or "sharp") and (, "teeth"), and the suffix

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns, adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can carr ...

' ("lizard"). It is currently known to have two species: ''C. saharicus'' and ''C. iguidensis''.

History of discovery

In 1924, two teeth were found in theContinental intercalaire

The Continental intercalaire, sometimes referred to as the Continental intercalaire Formation, is a term applied to Cretaceous strata in Northern Africa. It is the largest single stratum found in Africa to date, being between thick in some places. ...

of Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, showing what were at the time unique characteristics. These teeth were described by Depéret and Savornin (1925) as representing a new taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

, which they named ''Megalosaurus saharicus'' and later categorized in the subgenus

In biology, a subgenus (plural: subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between ...

'' Dryptosaurus''. Some years later, paleontologist Ernst Stromer

Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach (12 June 1871 in Nürnberg – 18 December 1952 in Erlangen) was a German paleontologist. He is best remembered for his expedition to Egypt, during which the first known remains of ''Spinosaurus'' we ...

described the remains of a partial skull and skeleton from Cenomanian

The Cenomanian is, in the ICS' geological timescale, the oldest or earliest age of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or the lowest stage of the Upper Cretaceous Series. An age is a unit of geochronology; it is a unit of time; the stage is a unit in ...

aged rocks in the Bahariya Formation

The Bahariya Formation (also transcribed as Baharija Formation) is a fossiliferous geologic formation dating back to the early Cenomanian, which outcrops within the Bahariya depression in Egypt, and is known from oil exploration drilling across ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

(Stromer, 1931); originally excavated in 1914, the remains consisted of a partial skull, teeth, vertebrae, claw bones and assorted hip and leg bones. The teeth in this new finding matched the characteristics of those described by Depéret and Savornin, which led to Stromer conserving the species name ''saharicus'' but finding it necessary to erect a new genus for this species, ''Carcharodontosaurus'', for their similarities, in sharpness and serrations, to the teeth of '' Carcharodon'' (Great white shark

The great white shark (''Carcharodon carcharias''), also known as the white shark, white pointer, or simply great white, is a species of large mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major oceans. It is nota ...

).

The fossils described by Stromer were destroyed in 1944 during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, but a new, more complete skull was found in the Kem Kem Group

The Kem Kem Group (commonly known as the Kem Kem beds) is a geological group in the Kem Kem region of eastern Morocco, whose strata date back to the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. Its strata are subdivided into two geological formations ...

of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

during an expedition led by paleontologist Paul Sereno

Paul Callistus Sereno (born October 11, 1957) is a professor of paleontology at the University of Chicago and a National Geographic "explorer-in-residence" who has discovered several new dinosaur species on several continents, including at si ...

in 1995, near the Algerian border and the locality where the teeth described by Depéret and Savornin (1925) were found. The teeth found with this new skull matched those described by Depéret and Savornin (1925) and Stromer (1931); the rest of the skull also matched that described by Stromer. This new skull was designated as the neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

by Brusatte and Sereno (2007) who also described a second species of ''Carcharodontosaurus'', ''C. iguidensis'' from the Echkar Formation

The Echkar Formation is a geological formation comprising sandstones and claystones in the Agadez Region of Niger, central Africa.

Description

Its strata date back to the Late Albian to Late Cretaceous ( Cenomanian stages, about 100-95 millio ...

of Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesmaxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

and braincase.

The taxonomy of ''Carcharodontosaurus'' was discussed in Chiarenza and Cau (2016), who suggested that the neotype of ''C. saharicus'' was similar but distinct from the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

in the morphology of the maxillary interdental plates. However, palaeontologist Mickey Mortimer put forward that the suggested difference between the ''C. saharicus'' neotype and holotype was actually due to damage to the neotype. The authors also identified the referred material of ''C. iguidensis'' as belonging to '' Sigilmassasaurus'' and a non- carcharodontosaurine, and therefore chose to limit ''C. iguidensis'' to the holotype pending future research.

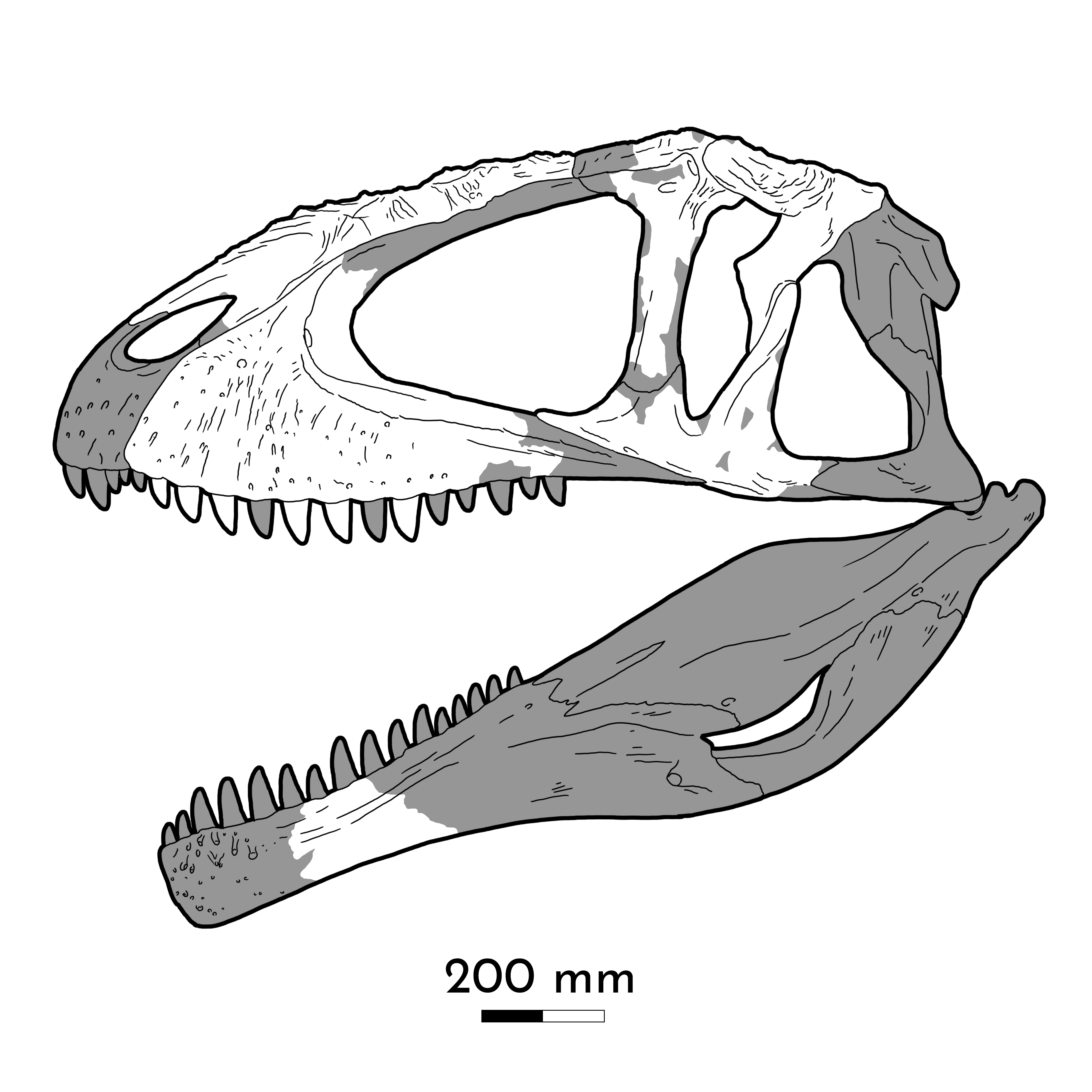

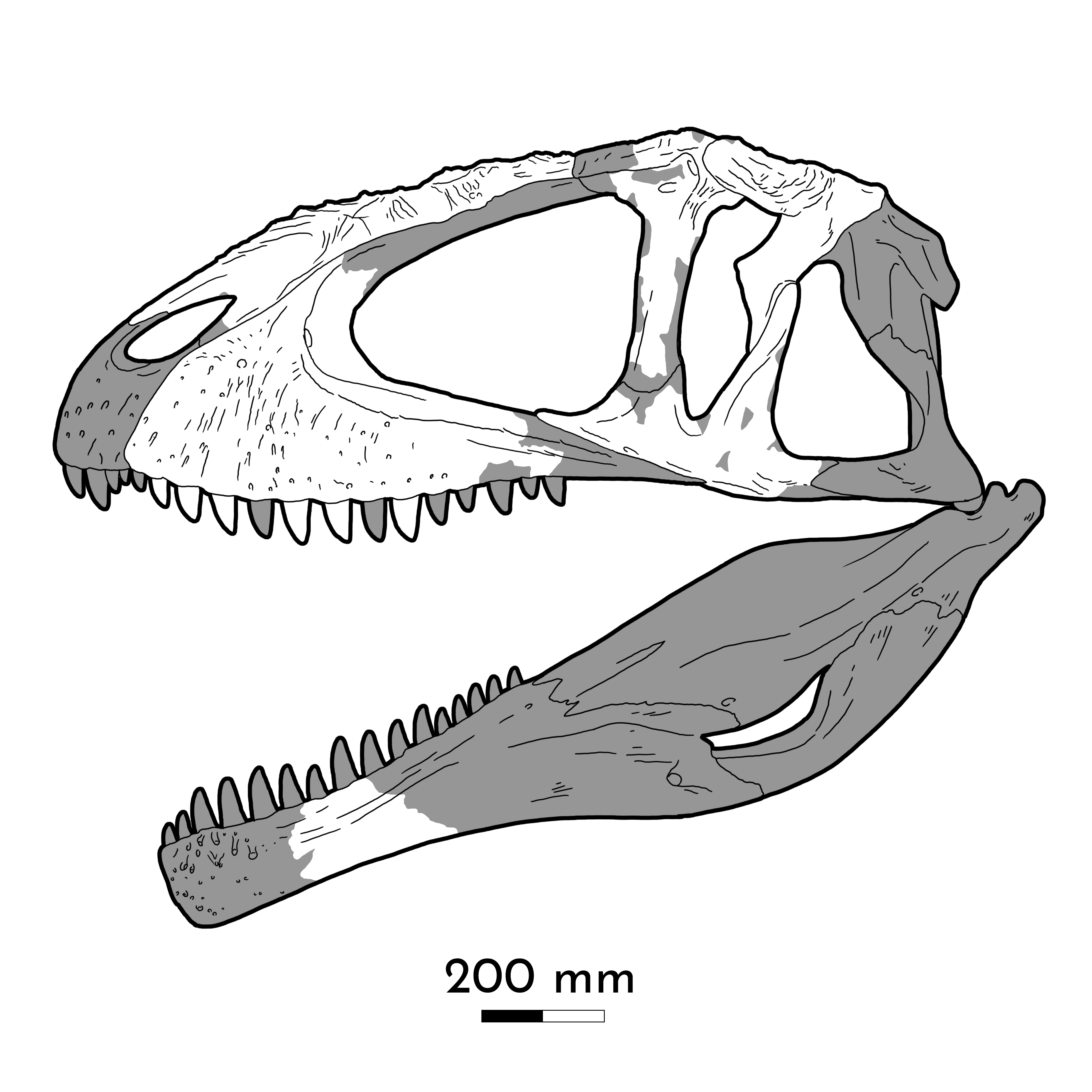

Description

''Carcharodontosaurus'' was one of the longest and heaviest known carnivorous dinosaurs, with an enormous long skull and long, serrated teeth up to long. ''C. saharicus'' reached in length and approximately in body mass, while ''C. iguidensis'' reached in length and in body mass.Brain and inner ear

In 2001, Hans C. E. Larsson published a description of theinner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in th ...

and endocranium

The endocranium in comparative anatomy is a part of the skull base in vertebrates and it represents the basal, inner part of the cranium. The term is also applied to the outer layer of the dura mater in human anatomy.

Structure

Structurally, ...

of ''Carcharodontosaurus saharicus''. Starting from the portion of the brain closest to the tip of the animal's snout is the forebrain, which is followed by the midbrain. The midbrain

The midbrain or mesencephalon is the forward-most portion of the brainstem and is associated with vision, hearing, motor control, sleep and wakefulness, arousal ( alertness), and temperature regulation. The name comes from the Greek ''mesos'', ...

is angled downwards at a 45-degree angle and towards the rear of the animal. This is followed by the hindbrain

The hindbrain or rhombencephalon or lower brain is a developmental categorization of portions of the central nervous system in vertebrates. It includes the medulla, pons, and cerebellum. Together they support vital bodily processes. Metencephal ...

, which is roughly parallel to the forebrain

In the anatomy of the brain of vertebrates, the forebrain or prosencephalon is the rostral (forward-most) portion of the brain. The forebrain (prosencephalon), the midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon) are the three primary ...

and forms a roughly 40-degree angle

In Euclidean geometry, an angle is the figure formed by two rays, called the '' sides'' of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the ''vertex'' of the angle.

Angles formed by two rays lie in the plane that contains the rays. Angles ...

with the midbrain. Overall, the brain of ''C. saharicus'' would have been similar to that of a related dinosaur, ''Allosaurus fragilis

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch ( Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alludi ...

''. Larsson found that the ratio of the cerebrum

The cerebrum, telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres), as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfactory bulb. ...

to the volume of the brain overall in ''Carcharodontosaurus'' was typical for a non-avian reptile. ''Carcharodontosaurus'' also had a large optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve is derived fro ...

.

The three semicircular canals of the inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in th ...

of ''Carcharodontosaurus saharicus'' – when viewed from the side – had a subtriangular outline. This subtriangular inner ear configuration is present in ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch ( Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alludin ...

'', lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia altho ...

s, turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked t ...

s, but not in birds. The semi-"circular" canals themselves were actually very linear, which explains the pointed silhouette. In life, the floccular lobe

The flocculus (Latin: ''tuft of wool'', diminutive) is a small lobe of the cerebellum at the posterior border of the middle cerebellar peduncle anterior to the biventer lobule. Like other parts of the cerebellum, the flocculus is involved in mot ...

of the brain would have projected into the area surrounded by the semicircular canals, just like in other non-avian theropods, birds, and pterosaurs

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to 6 ...

.

Classification

The following cladogram after Apesteguía ''et al.'', 2016, shows the placement of ''Carcharodontosaurus'' within Carcharodontosauridae.

The following cladogram after Apesteguía ''et al.'', 2016, shows the placement of ''Carcharodontosaurus'' within Carcharodontosauridae.

Paleobiology

Feeding

A study by Donald Henderson, the curator of dinosaurs at theRoyal Tyrrell Museum

The Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology (RTMP, and often referred to as the Royal Tyrrell Museum) is a palaeontology museum and research facility in Drumheller, Alberta, Canada. The museum was named in honour of Joseph Burr Tyrrell, and is situ ...

suggests that ''Carcharodontosaurus'' was able to lift animals weighing a maximum of in its jaws based on the strength of its jaws, neck, and its center of mass.

Pathology

SGM-Din 1, a ''Carcharodontosaurus saharicus'' skull, has a circular puncture wound in the nasal and "an abnormal projection of bone on the antorbital rim.""Acrocanthosauridae fam. nov.," in Molnar (2001). Pg. 342.References

External links

Student Identifies Enormous New Dinosaur December 7 2007 from the Science daily

{{Taxonbar, from=Q14431 Carcharodontosaurids Late Cretaceous dinosaurs of Africa Cenomanian genus extinctions Bahariya Formation Fossil taxa described in 1931 Taxa named by Ernst Stromer Apex predators Cenomanian life