Cyanidioschyzon Merolae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cyanidioschyzon merolae'' is a small (2μm), club-shaped, unicellular

genome comparison table

The reduced nature of the genome has led to several other unusual features. While most eukaryotes contain 10 or so copies of the

''Cyanidioschyzon merolae'' Genome Project

haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for Autosome, autosomal and Pseudoautosomal region, pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the num ...

red alga

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), make up one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta comprises one of the largest Phylum, phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 recognized species within over 900 Genus, genera amidst ongoing taxon ...

adapted to high sulfur acidic hot spring environments (pH 1.5, 45 °C). The cellular architecture of ''C. merolae'' is extremely simple, containing only a single chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

and a single mitochondrion

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cell (biology), cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine tri ...

and lacking a vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in Plant cell, plant and Fungus, fungal Cell (biology), cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water ...

and cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

. In addition, the cellular and organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

divisions can be synchronized. For these reasons, ''C. merolae'' is considered an excellent model system for study of cellular and organelle division processes, as well as biochemistry

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, a ...

and structural biology

Structural biology deals with structural analysis of living material (formed, composed of, and/or maintained and refined by living cells) at every level of organization.

Early structural biologists throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries we ...

. The organism's genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

was the first full algal genome to be sequenced in 2004; its plastid was sequenced in 2000 and 2003, and its mitochondrion in 1998. The organism has been considered the simplest of eukaryotic cells for its minimalist cellular organization.

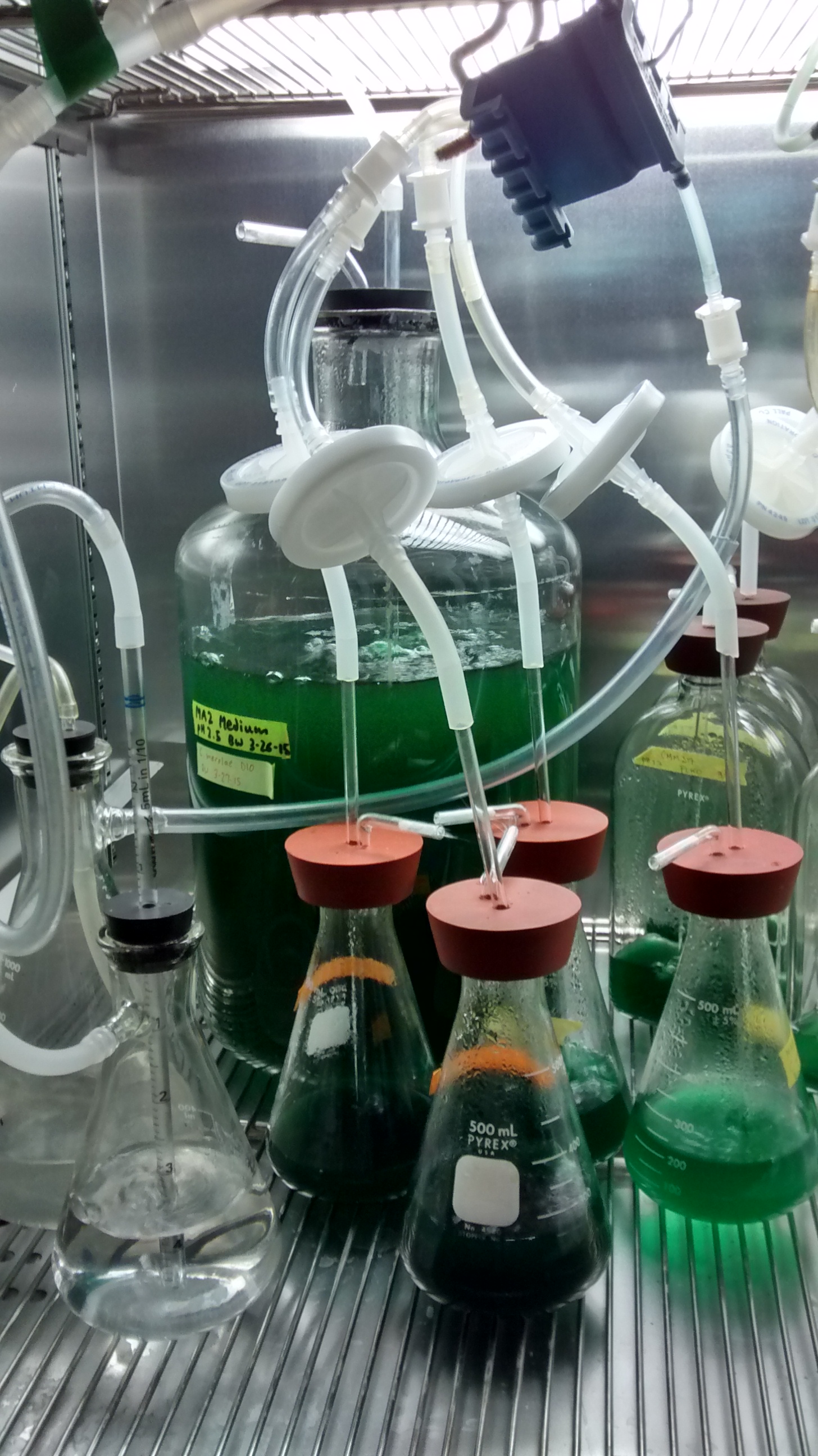

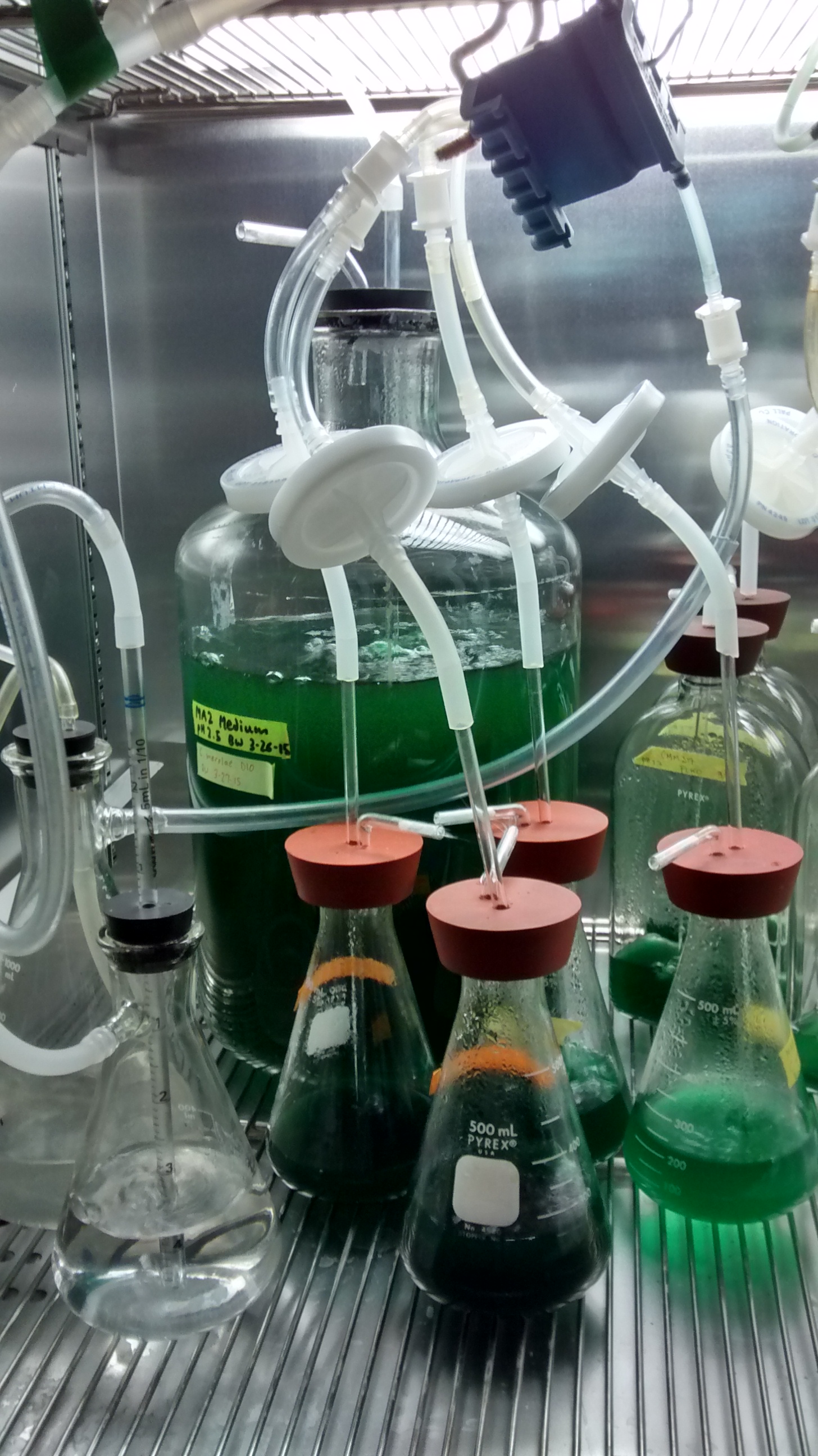

Isolation and growth in culture

Originally isolated by De Luca in 1978 from the solfatane fumaroles of Campi Flegrei ( Naples, Italy), ''C. merolae'' can be grown inculture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

in the laboratory in Modified Allen's medium (MA) or a modified form with twice the concentration of some elements called MA2. Using MA medium, growth rates are not particularly fast, with a doubling time (the time it takes a culture of microbes to double in cells per unit volume) of approximately 32 hours. By using the more optimal medium MA2, this can be reduced to 24 hours. Culturing is done at under white fluorescent light with an approximate intensity of 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (μE). However, under a higher light intensity of 90 μE with 5% CO2 applied through bubbling, the growth rate of ''C. merolae'' can be further increased, with a doubling time of approximately 9.2 hours. Higher light is not necessarily beneficial, as above 90 μE the growth rate begins to decrease. This may be due to photodamage occurring to the photosynthetic apparatus. ''C. merolae'' can also be grown on gellan gum plates for purposes of colony selection or strain maintenance in the laboratory. ''C. merolae'' is an obligate oxygenic phototroph, meaning it is not capable of taking up fixed carbon from its environment and must rely on oxygenic photosynthesis to fix carbon from CO2.

Genome

The 16.5 megabase pairgenome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

of ''C. merolae'' was sequenced in 2004. The reduced, extremely simple, compact genome is made up of 20 chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

s and was found to contain 5,331 genes, of which 86.3% were found to be expressed and only 26 contain intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e., a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gen ...

s, which contained strict consensus sequences. Strikingly, the genome of ''C. merolae'' contains only 30 tRNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

genes and an extremely minimal number of ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

gene copies, as shown in thgenome comparison table

The reduced nature of the genome has led to several other unusual features. While most eukaryotes contain 10 or so copies of the

dynamin

Dynamin is a GTPase protein responsible for endocytosis in the eukaryotic cell. Dynamin is part of the "dynamin superfamily", which includes classical dynamins, dynamin-like proteins, MX1, Mx proteins, OPA1, MFN1, mitofusins, and Guanylate-bindin ...

s required for pinching membranes to separate dividing compartments, ''C. merolae'' only contains two, a fact that researchers have taken advantage of when studying organelle division.

Although possessing a small genome, the chloroplast genome of ''C. merolae'' contains many genes not present in the chloroplast genomes of other algae and plants. Most of its genes are intronless.

Molecular biology

As is the case with most model organisms, genetic tools have been developed in ''C. merolae''. These include methods for the isolation ofDNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

from ''C. merolae'', the introduction of DNA into ''C. merolae'' for transient or stable transformation, and methods for selection including a uracil auxotroph that can be used as a selection marker.

DNA isolation

Several methods, derived fromcyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

l protocols, are used for the isolation of DNA from ''C. merolae''. The first is a hot phenol

Phenol (also known as carbolic acid, phenolic acid, or benzenol) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile and can catch fire.

The molecule consists of a phenyl group () ...

extraction, which is a quick extraction that can be used to isolate DNA suitable for DNA amplification polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR), wherein phenol is added to whole cells and incubated at 65 °C to extract DNA. If purer DNA is required, the Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method may be employed. In this method, a high-salt extraction buffer is first applied and cells are disrupted, after which a chloroform-phenol mixture is used to extract the DNA at room temperature.

RNA isolation

Total RNA may be extracted from ''C. merolae'' cells using a variant of the hot phenol method described above for DNA.Protein extraction

As is the case for DNA and RNA, the protocol for protein extraction is also an adaptation of the protocol used in cyanobacteria. Cells are disrupted using glass beads and vortexing in a 10%glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

buffer containing the reducing agent DTT to break disulfide bond

In chemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) is a compound containing a functional group or the anion. The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and usually derived from two thiol groups.

In inor ...

s within proteins. This extraction will result in denatured proteins, which can be used in SDS-PAGE gels for Western blotting

The western blot (sometimes called the protein immunoblot), or western blotting, is a widely used analytical technique in molecular biology and immunogenetics to detect specific proteins in a sample of tissue homogenate or extract. Besides detec ...

and Coomassie staining.

Transformant selection and uracil auxotrophic line

''C. merolae'' is sensitive to manyantibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

commonly used for selection of successfully transformed individuals in the laboratory, but it resistant to some, notably ampicillin

Ampicillin is an antibiotic belonging to the aminopenicillin class of the penicillin family. The drug is used to prevent and treat several bacterial infections, such as respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, meningitis, s ...

and kanamycin

Kanamycin A, often referred to simply as kanamycin, is an antibiotic used to treat severe bacterial infections and tuberculosis. It is not a first line treatment. It is used by mouth, injection into a vein, or injection into a muscle. Kanamy ...

.

A commonly used selection marker for transformation in ''C. merolae'' involves a uracil

Uracil () (nucleoside#List of nucleosides and corresponding nucleobases, symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleotide bases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via ...

auxotroph (requiring exogenous uracil). The mutant was developed by growing ''C. merolae'' in the presence of a compound, 5-FOA, which in and of itself is non-toxic but is converted to the toxic compound 5-Fluorouracil by an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

in the uracil biosynthetic pathway, orotidine 5'-monophosphate (OMP) decarboxylase, encoded by the ''Ura5.3'' gene. Random mutation led to several loss-of-function mutants in ''Ura5.3'', which allowed cells to survive in the presence of 5-FOA as long as uracil was provided. By transforming this mutant with a PCR fragment carrying both a gene of interest and a functional copy of ''Ura5.3'', researchers can confirm that the gene of interest has been incorporated into the ''C. merolae'' genome if it can grow without exogenous uracil.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) mediated transient expression

While chromosomal integration of genes creates a stable transformant, transient expression allows short-term experiments to be done using labeled or modified genes in ''C. merolae''. Transient expression can be achieved using apolyethylene glycol

Polyethylene glycol (PEG; ) is a polyether compound derived from petroleum with many applications, from industrial manufacturing to medicine. PEG is also known as polyethylene oxide (PEO) or polyoxyethylene (POE), depending on its molecular wei ...

(PEG) based method in protoplasts (plant cells with the rigid cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

enzymatically eliminated), and because ''C. merolae'' lacks a cell wall, it behaves much as a protoplast

Protoplast (), is a biology, biological term coined by Johannes von Hanstein, Hanstein in 1880 to refer to the entire cell, excluding the cell wall. Protoplasts can be generated by stripping the cell wall from plant, bacterium, bacterial, or f ...

would for transformation purposes. To transform, cells are briefly exposed to 30% PEG with the DNA of interest, resulting in transient transformation. In this method, the DNA is taken up as a circular element and is not integrated into the genome of the organism because no homologous regions exist for integration.

Gene targeting

To create a stable mutant line, gene targeting can be used to insert a gene of interest into a particular location of the ''C. merolae'' genome viahomologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in Cell (biology), cellular organi ...

. By including regions of DNA several hundred base pairs long on the ends of the gene of interest that are complementary to a sequence within the ''C. merolae'' genome, the organism's own DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell (biology), cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is cons ...

machinery can be used to insert the gene at these regions. The same transformation procedure as is used for transient expression can be used here, except with the homologous DNA segments to allow for genome integration.

Studying cell and organelle divisions

The extremely simple divisome, simple cell architecture, and ability to synchronize divisions in ''C. merolae'' makes it the perfect organism for studying mechanisms of eukaryotic cell and organelle division. Synchronization of the division of organelles in cultured cells can be very simple and usually involves the use of light and dark cycles. The chemical agent aphidicolin can be added to easily and effectively synchronize chloroplast division. Theperoxisome

A peroxisome () is a membrane-bound organelle, a type of microbody, found in the cytoplasm of virtually all eukaryotic cells. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Frequently, molecular oxygen serves as a co-substrate, from which hydrogen perox ...

division mechanism was first ascertained using ''C. merolae'' as a system, where peroxisome division can be synchronized using the microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nanometer, nm and have an inner diameter bet ...

-disrupting drug oryzalin

Oryzalin is a herbicide of the dinitroaniline class. It acts through the disruption ( depolymerization) of microtubules, thus blocking anisotropic growth of plant cells. It can also be used to induce polyploidy in plants as an alternative to co ...

in addition to light-dark cycles.

Photosynthesis research

''C. merolae'' is also used in researchingphotosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

. Notably, the subunit composition of the photosystems in ''C. merolae'' has some significant differences from that of other related organisms. Photosystem II (PSII) of ''C. merolae'', as might be expected, has a particularly unusual pH range in which it can function. Despite the fact that the mechanism of PSII requires protons to be quickly released, and lower pH solutions should alter the ability to do this, ''C. merolae'' PSII is capable of exchanging and splitting water at the same rate as other related species.

See also

* '' Galdieria sulphuraria'' *Red algae

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), make up one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta comprises one of the largest Phylum, phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 recognized species within over 900 Genus, genera amidst ongoing taxon ...

External links

''Cyanidioschyzon merolae'' Genome Project

References

{{Reflist Cyanidiophyceae Species described in 1978